BACKGROUND

Dedicated registries, such as Get With The Guidelines® (GWTG)-Resuscitation, have greatly advanced our understanding of care strategies and outcomes for in-hospital cardiac arrest.1,2 Several recent investigations have attempted to broaden understanding of outcomes among non-registry hospitals using billing codes for cardiac arrest or cardiopulmonary resuscitation to identify cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest.3–5 However, the validity of using administrative billing data to study in-hospital cardiac arrest remains unknown.

METHODS

Using linked data between GWTG-Resuscitation (a large prospective registry of confirmed cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest) and fee-for-service Medicare claims data,6 we evaluated the sensitivity of administrative claims data in identifying verified cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest from a clinical registry. Within GWTG-Resuscitation, a total of 56,678 patients ≥65 years of age from 545 hospitals with an in-hospital cardiac arrest between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2012 were linked to Medicare claims files.

We assessed the proportion of cardiac arrest cases from GWTG-Resuscitation that were identified in corresponding Medicare claims using International Classification of Disease –9th Edition Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes for cardiac arrest (427.5 [cardiac arrest], 427.1 [ventricular tachycardia], 427.41 [ventricular fibrillation] or 427.42 [ventricular flutter]) or procedure codes for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ICD-9-CM codes 99.60, 99.63) or defibrillation (ICD-9-CM code 99.62). Further, among GWTG-Resuscitation hospitals with ≥10 cases, we examined hospital-level variation in rates of administrative capture for cardiac arrest with each strategy. We also describe this variation using median odds ratio, which quantifies the average site-level variation in capture rates for two identical patients. Finally, we compared rates of survival to discharge with each strategy to the observed survival rate in the reference GWTG-Resuscitation cohort.

RESULTS

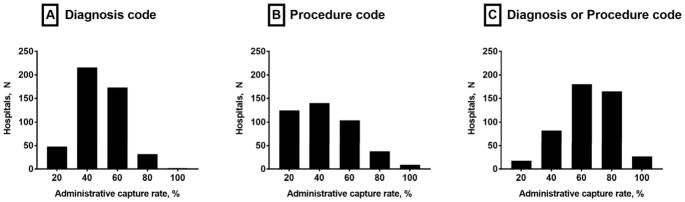

Of 56,678 patients in GWTG-Resuscitation, 26,547 (46.8%) were identified using diagnosis codes for cardiac arrest and 21,096 (37.2%) with procedure codes for cardiopulmonary resuscitation or defibrillation. A total of 11,882 (21.0%) had both a diagnosis and procedure code, and 20,917 (36.9%) were not identified with any billing data (Table). There was substantial hospital-level variation in identifying cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest using administrative data (Figure), with a median odds ratio of 1.63 (95% CI: 1.57–1.70) using diagnosis codes and 2.92 (95% CI: 2.71–3.18) using procedure codes. Use of diagnosis or procedure codes to identify patients with an in-hospital cardiac arrest had significant implications for survival outcomes. Compared to an 18.7% rate of survival to hospital discharge in the reference GWTG-Resuscitation cohort, those identified as having an in-hospital cardiac arrest using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes had a survival rate of 28.4%, whereas those identified using ICD-9-CM procedure codes or not identified at all had survival rates of 15.7% and 12.0%, respectively (P-values <0.05 for all, compared with the GWTG-Resuscitation cohort).

Table 1. Accuracy of Administrative Claims-based Approaches in Capturing Cases of In-hospital Cardiac Arrest, and the Respective Survival Estimates with Each Approach.

Of 56,678 patients with an in-hospital cardiac arrest in GWTG-Resuscitation, the proportion of patients identified using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes and procedure codes, and the corresponding survival estimates, are summarized.

| Study group | Case Capture | Survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N | Percent | N | Percent | |

| GWTG-Resuscitation (reference) | 56,678 | 10,624 | 18.7% | |

|

| ||||

| ICD-9-CM Billing Code Category | ||||

| Any diagnosis code1 | 26,547 | 46.8% | 7533 | 28.4% |

| Any procedure code2 | 21,096 | 37.2% | 3302 | 15.7% |

| Either a diagnosis or a procedure code1,2 | 35761 | 63.1% | 8119 | 22.7% |

| Both a diagnosis and a procedure code1,2 | 11,882 | 21.0% | 2716 | 22.9% |

| No diagnosis or procedure code | 20,917 | 36.9% | 2505 | 12.0% |

Abbreviations: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases – 9th Edition Clinical Modification

ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 427.5, 427.41, and 427.42,

ICD-9-CM procedure codes 99.60, 99.62, or 99.63

Figure 1. Hospital variation in the sensitivity of Medicare data to identify in-hospital cardiac arrests in GWTG-Resuscitation.

Wide hospital variation exists in the sensitivity of using administrative data to capture confirmed cases of in-hospital cardiac arrests in GWTG-Resuscitation using (A) diagnostic codes only, (B) procedure codes only, and (C) either a diagnostic or procedure code for cardiac arrest or resuscitation.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 56,678 patients with confirmed in-hospital cardiac arrest, we identified several key limitations of using administrative data for cardiac arrest research. Most studies have used a diagnosis or procedure code alone to identify cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest. However, we found that the majority of confirmed cases in a national registry would not be captured using either administrative data strategy. Furthermore, survival rates using administrative data to identify cases from the same reference population varied markedly and were 52% higher (28.4% vs. 18.7%) when using diagnosis codes alone to identify in-hospital cardiac arrest. Finally, there was large hospital variation in documenting diagnosis or procedure codes for patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest, which would have consequences for using administrative data to examine hospital-level variation in cardiac arrest incidence or survival, or conducting single-center studies to validate this administrative approach. Collectively, our study highlights the challenges of using administrative billing data to conduct research on in-hospital cardiac arrest.

LIMITATION

Our study did not evaluate the positive predictive value of cardiac arrest cases identified using administrative codes, or assess whether GWTG-Resuscitation captures all cardiac arrest cases in hospitals. De-identification of data within GWTG-Resuscitation Medicare files precluded such analyses, but these additional issues are important areas of research in future studies.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Khera (5T32HL125247-02, UL1TR001105) is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Chan (R01HL123980) and Dr. Girotra (K08HL122527) are supported by funding from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Neither funding agency had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

- Dr. Chan has served as a consultant for the American Heart Association. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest or financial interests to disclose.

- GWTG-Resuscitation is sponsored by the American Heart Association, which had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The manuscript is reviewed and approved by the GWTG-Resuscitation research and publications committee prior to journal submission.

References

- 1.Khera R, Chan PS, Donnino M, Girotra S American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation I. Hospital Variation in Time to Epinephrine for Nonshockable In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Circulation. 2016;134(25):2105–2114. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girotra S, Nallamothu BK, Spertus JA, et al. Trends in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1912–1920. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, et al. Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):22–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolte D, Khera S, Aronow WS, et al. Regional variation in the incidence and outcomes of in-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States. Circulation. 2015;131(16):1415–1425. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fugate JE, Brinjikji W, Mandrekar JN, et al. Post-cardiac arrest mortality is declining: a study of the US National Inpatient Sample 2001 to 2009. Circulation. 2012;126(5):546–550. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.088807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan PS, Nallamothu BK, Krumholz HM, et al. Long-term outcomes in elderly survivors of in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(11):1019–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]