Abstract

Aims

Proprietary Chinese medicines (pCMs) and health products, generally believed to be natural and safe, are gaining popularity worldwide. However, the safety of pCMs and health products has been severely compromised by the practice of adulteration. The current study aimed to examine the problem of adulteration of pCMs and health products in Hong Kong.

Methods

The present study was conducted in a tertiary referral clinical toxicology laboratory in Hong Kong. All cases involving the use of pCMs or health products, which were subsequently confirmed to contain undeclared adulterants, from 2005 to 2015 were reviewed retrospectively.

Results

A total of 404 cases involving the use of 487 adulterated pCMs or health products with a total of 1234 adulterants were identified. The adulterants consisted of approved drugs, banned drugs, drug analogues and animal thyroid tissue. The six most common categories of adulterants detected were nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (17.7%), anorectics (15.3%), corticosteroids (13.8%), diuretics and laxatives (11.4%), oral antidiabetic agents (10.0%) and erectile dysfunction drugs (6.0%). Sibutramine was the most common adulterant (n = 155). The reported sources of these illicit products included over‐the‐counter drug stores, the internet and Chinese medicine practitioners. A significant proportion of patients (65.1%) had adverse effects attributable to these illicit products, including 14 severe and two fatal cases. Psychosis, iatrogenic Cushing syndrome and hypoglycaemia were the three most frequently encountered adverse effects.

Conclusions

Adulteration of pCMs and health products with undeclared drugs poses severe health hazards. Public education and effective regulatory measures are essential to address the problem.

Keywords: drug adulteration, health products, poisoning, proprietary Chinese medicines

What is Already Known about this Subject

Proprietary Chinese medicines (pCMs) and health products, generally believed to be natural and safe, are gaining popularity worldwide.

Adulteration of pCMs and health products with undeclared drugs has been reported previously but this was limited mainly to routine surveillance data or case reports/series with a small number of affected patients.

What this Study Adds

A wide variety of adulterants, including approved drugs, banned drugs, drug analogues and animal thyroid tissue, were identified.

Adverse effects were seen in a significant proportion of patients, including severe and even fatal cases.

Introduction

Traditional Chinese medicine is widely used all over the world as a form of complementary medicine for various indications and for improving general health, especially in Chinese communities. A survey in Hong Kong in 2014 showed that 18% of residents who had had medical consultations in the previous 30 days had consulted a Chinese medicine practitioner 1. Another survey in 1994 revealed that 45% of Singaporeans had consulted a Chinese medicine practitioner at some time, and that 19% had consulted one in the previous year 2. The use of proprietary Chinese medicines (pCMs), which are composed solely of Chinese medicines and formulated in a finished dose form, is particularly popular because of their convenience and ready accessibility. There is also an ever‐growing market worldwide for a variety of health products, which contain herbal or other natural ingredients with claimed nutritional, physiological or health‐promoting effects.

The increasing popularity of these pCMs and health products may be attributed to the general belief that these products are ‘natural and safe’. However, this assumption may not always hold true. Adulteration of pCMs and health products with undeclared agents, including prescription drugs, drug analogues and banned drugs, has been reported 3, 4, 5. Potentially fatal adverse effects could result from the use of these illicit products. As the only tertiary referral clinical toxicology laboratory in Hong Kong, our centre has encountered numerous poisoning cases related to the use of adulterated pCMs or health products throughout the years. To examine the problem, we retrospectively reviewed cases involving use of pCMs or health products adulterated with undeclared drugs referred to the centre from 2005 to 2015.

Methods

From January 2005 to December 2015, all cases referred to the Hospital Authority Toxicology Reference Laboratory involving use of pCMs or health products, which were subsequently confirmed to contain undeclared adulterants, were reviewed retrospectively. Clinical data were collected by reviewing the laboratory database as well as the patients’ medical records. Demographic data, clinical presentation, medical history, drug history, laboratory findings and the analytical findings of the pCMs and health products were studied. The causal relationship between the clinical features, if any, and the adulterants detected was evaluated based on the known adverse effects of the adulterants, the temporal sequence, as well as the presence of any other underlying diseases. If poisoning was ascertained, the severity was graded according to an established poisoning severity score 6.

Qualitative general toxicology screen using high‐performance liquid chromatography with a diode array detector was performed on the pCM and health product specimens. Confirmatory analysis employing gas chromatography mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) was performed as indicated. Detection of animal thyroid tissue was carried out by LC–MS/MS after protein digestion.

The study was approved by the Hong Kong Hospital Authority Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee [approval number KW/EX‐16‐116(101–06)]. The Committee exempted the study group from obtaining patient consent because the presented data were anonymous and the risk of identification was low.

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 7.

Results

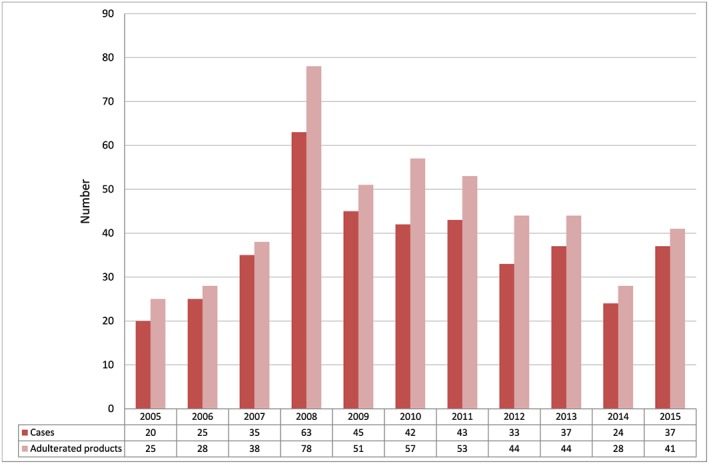

A total of 404 cases, involving the use of 487 adulterated pCMs or health products, were identified in the authors’ laboratory during the study period. The patients were referred from 22 different local hospitals. There were 236 (58%) females and 168 (42%) males. The age of the patients ranged from 1 month to 90 years, and the median age was 51 years. The numbers of cases and adulterated products identified over the 11 years are shown in Figure 1. Data from some of the cases in earlier years, involving subgroup analysis of weight‐reducing agents, herbal antidiabetic products, corticosteroid‐adulterated pCMs and sexual enhancement products, have been previously published 8, 9, 10, 11, 12.

Figure 1.

Number of cases and adulterated proprietary Chinese medicines/health products detected from 2005 to 2015

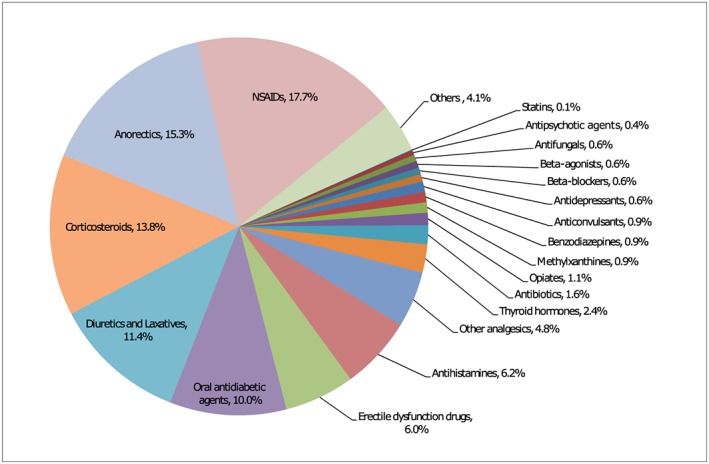

Among the 487 adulterated products, pCMs and health products constituted 61% (n = 299) and 39% (n = 188), respectively. Brand names and/or packages were available in 60% (n = 291) of the adulterated products. In total, 1234 adulterants were detected in the illicit products, with an average of 2.5 adulterants per product. In the most extreme case, up to 17 adulterants [comprising corticosteroid, multiple nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and other drugs] were detected in a single product indicated for pain. The adulterants consisted of approved drugs, banned drugs, drug analogues and animal thyroid tissue. The six most common categories of adulterants detected were NSAIDs (17.7%), anorectics (15.3%), corticosteroids (13.8%), diuretics and laxatives (11.4%), oral antidiabetic agents (10.0%) and erectile dysfunction drugs (6.0%). Details of the various categories of adulterants are shown in Figure 2. The top 21 frequently encountered adulterants are listed in Table 1. Sibutramine, an anorectic, was the most common adulterant and was present in 31.8% (n = 155) of the illicit products. It was followed by phenolphthalein, a banned laxative commonly adulterated together with sibutramine, which was detected in 18.1% (n = 88) of the adulterated products. Glibenclamide (12.5%), diclofenac (12.3%), prednisone acetate (11.5%), sildenafil (11.1%), chlorpheniramine (10.1%) and piroxicam (10.1%) were also found in more than one‐tenth of the samples. Compatible with the pattern of adulteration, common reported indications for the use of these adulterated products consisted of weight reduction (n = 179; 36.8%), various pain conditions such as joint pain, gout and rheumatism (n = 111; 22.8%), erectile dysfunction (n = 44; 9.0%), diabetes (n = 43; 8.8%) and skin disorders such as eczema and psoriasis (n = 29; 6.0%). Details of the various indications are shown in Table 2. Sources of the adulterated pCMs or health products as reported by the patients were available in 220 out of the 487 samples (45%). These sources included over‐the‐counter drug stores (n = 74; 33.6%), the internet (n = 57; 25.9%), Chinese medicine practitioners (n = 54; 24.5%), relatives and friends (n = 26; 11.8%), beauty salons (n = 8; 3.6%) and street vendor (n = 1; 0.5%). The samples were obtained mainly in Hong Kong or mainland China, and occasionally from other countries.

Figure 2.

Categories of the 1234 adulterants detected in the 487 proprietary Chinese medicines/health products. NSAID, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

Table 1.

Top 21 common adulterants detected in the proprietary Chinese medicines (pCMs)/health products

| Ranking | Adulterant | Frequency of detection | Percentage in all adulterants | Percentage in all pCMs/health products |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sibutramine | 155 | 12.6% | 31.8% |

| 2 | Phenolphthalein | 88 | 7.1% | 18.1% |

| 3 | Glibenclamide | 61 | 4.9% | 12.5% |

| 4 | Diclofenac | 60 | 4.9% | 12.3% |

| 5 | Prednisone acetate | 56 | 4.5% | 11.5% |

| 6 | Sildenafil | 54 | 4.4% | 11.1% |

| 7 | Chlorpheniramine | 49 | 4.0% | 10.1% |

| 8 | Piroxicam | 49 | 4.0% | 10.1% |

| 9 | Indomethacin | 46 | 3.7% | 9.4% |

| 10 | Dexamethasone | 44 | 3.6% | 9.0% |

| 11 | Paracetamol | 36 | 2.9% | 7.4% |

| 12 | Phenformin | 35 | 2.8% | 7.2% |

| 13 | Ibuprofen | 32 | 2.6% | 6.6% |

| 14 | Hydrochlorothiazide | 31 | 2.5% | 6.4% |

| 15 | Animal thyroid tissue | 26 | 2.1% | 5.3% |

| 16 | Dexamethasone acetate | 24 | 1.9% | 4.9% |

| 17 | Phenylbutazone | 14 | 1.1% | 2.9% |

| 18 | Metoclopramide | 14 | 1.1% | 2.9% |

| 19 | Betamethasone | 12 | 1.0% | 2.5% |

| 20 | Fenfluramine | 12 | 1.0% | 2.5% |

| 21 | Cimetidine | 12 | 1.0% | 2.5% |

Table 2.

Indications for the use of the 487 adulterated proprietary Chinese medicines (pCMs)/health products

| Indication | Number of adulterated pCMs health products (%) |

|---|---|

| Weight reduction | 179 (36.8%) |

| Pain (e.g. joint pain, gout, rheumatism) | 111 (22.8%) |

| Erectile dysfunction | 44 (9.0%) |

| Diabetes | 43 (8.8%) |

| Skin disorders (e.g. eczema, psoriasis) | 29 (6.0%) |

| Airway problems (e.g. asthma, chronic obstructive airway disease) | 16 (3.3%) |

| Improving general well‐being | 9 (1.8%) |

| Convulsion | 4 (0.8%) |

| Insomnia | 4 (0.8%) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 3 (0.6%) |

| Hypertension | 2 (0.4%) |

| Others | 8 (1.6%) |

| Unknown | 35 (7.2%) |

Overall, 263 (65.1%) patients had one or more adverse effects that were attributable to the adulterated pCMs or health products. Of these ascertained poisoning cases, the severity was as follows: fatal (n = 2), severe (n = 14), moderate (n = 204) and minor (n = 43). The major clinical presentation of the patients was usually the known adverse effects of anorectics, corticosteroids, oral antidiabetic agents, NSAIDs and animal thyroid tissue, which included psychosis (n = 52), iatrogenic Cushing syndrome (n = 43), hypoglycaemia (n = 41), palpitations (n = 30), renal impairment (n = 30), abnormal thyroid function (n = 24), deranged liver function (n = 23) and adrenal insufficiency (n = 18). Details of the adulterated pCMs and health products, and the associated clinical features of the 16 cases with fatal or severe poisoning are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the 16 cases with fatal or severe poisoning associated with the use of adulterated proprietary Chinese medicines (pCMs)/health products

| Gender/age | Name of pCMs / health products | Indication | Source of pCMs / health products | Duration of use | Adulterants detected | Associated adverse effects (severity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/53y | Chang Qing Chun (常青春) | Weight reduction | Mainland China | Unknown | N‐Nitrosofenfluramine, fenfluramine, sibutramine, phenolphthalein, propranolol, animal thyroid tissue | Valvular heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, cardiac arrest, abnormal thyroid function (fatal) |

| F/21y | Bai Bang Mei Qu Qing Jiao Nang (百邦美曲輕膠囊) | Weight reduction | Mainland China | 1 month | Sibutramine, N‐desmethyl‐sibutramine | Ventricular fibrillation, cardiac arrest (fatal) |

| M/56y | Yi Su Kang Jiao Nang (胰速康膠囊) | Diabetes | Over‐the‐counter, mainland China | 10 months | Phenformin, glibenclamide | Lactic acidosis (severe) |

| M/1 m | Lan Mei Ke Li Ji (藍梅顆粒劑) | Unknown | Mainland China | Unknown | Gliclazide | Hypoglycaemia, seizure (severe) |

| F/37y | Protein OB Capsule | Weight reduction | Mainland China | Unknown | Sibutramine | Acute coronary syndrome (severe) |

| M/67y | Nan Gen Zeng Chang Su (男根增長素) | Erectile dysfunction | Mainland China | Unknown | Sildenafil, tadalafil, glibenclamide | Hypoglycaemia, loss of consciousness (severe) |

| M/84y | Mi Fang Feng Shi Wang Jiao Nang (秘方風濕王膠囊) | Pain | Unknown | 2 years | Prednisone acetate, piroxicam, indomethacin, ibuprofen, trimethoprim | Iatrogenic Cushing syndrome, multiple osteoporotic fractures (severe) |

| M/64y | Shen Ji Xi Jiao Wan (參薺犀角丸) | Diabetes | Unknown | Unknown | Metformin, phenformin, glibenclamide | Lactic acidosis, hypoglycaemia (severe) |

| F/34y | Qing Shen Le Jian Fei Jiao Nang (輕身樂減肥膠囊) | Weight reduction | Unknown | 6 months | Fenfluramine, sibutramine, nifedipine, phenolphthalein, animal thyroid tissue | Valvular heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, abnormal thyroid function (severe) |

| M/66y | Sheng Shou Pai Jie Shi Jiao Nang (聖首牌芥蓍膠囊) | Diabetes | Mainland China | Unknown | Glibenclamide, phenformin | Hypoglycaemia (severe) |

| M/66y | Unknown | Pain | Hong Kong | 1–2 years | Prednisolone, dexamethasone, piroxicam, amitriptyline | Renal impairment (severe) |

| F/48y | Qing Zi Lu Cha Jiao Nang (輕姿綠茶膠囊) | Weight reduction | Mainland China | 2–3 years | Sibutramine, phenolphthalein | Heart failure (severe) |

| F/79y | Ri Ben Ta Pai Zuo Gu Tong Wan (日本塔牌坐骨痛丸) | Pain | Over‐the‐counter, Hong Kong | 4 months | Indomethacin | Gastrointestinal bleeding, renal impairment (severe) |

| M/67y | Xuan Tai Shu Jiao Nang (癬泰舒膠囊) | Psoriasis | Mainland China | 2 months | Prednisone acetate | Pseudomonas pneumonia, lung abscess, septic shock (severe) |

| M/68y | Quan Xie Jin Gu Tong (全蝎筋骨通) | Pain | Over‐the‐counter, mainland China | 1.5 years | Prednisone acetate, piroxicam, diclofenac | Recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding (severe) |

| M/46y | Jia Rong Zhuang Gu Tong Bi Jiao Nang (甲茸壯骨通痹膠囊) | Pain | Mainland China | 10 years | Prednisone acetate, indomethacin, ibuprofen, diclofenac, phenylbutazone, naproxen, piroxicam, nefopam, paracetamol, cimetidine, metoclopramide, chlorzoxazone, chlorpheniramine, hydrochlorothiazide, dioxopromethazine, theophylline, trimethoprim | Secondary adrenal insufficiency, renal impairment, peptic ulcer (severe) |

Discussion

Adulteration of pCMs and health products with undeclared drugs has become a global problem. A study in Taiwan in 1992–1993 showed that 23.7% of 2609 pCM samples were adulterated with synthetic drugs 3, while regular checks of pCMs for undeclared drugs in Singapore between 1990 and 1997 revealed 32 (1.5%) adulterated pCMs out of 2080 samples 4. A systematic review of the world literature regarding adulteration of pCMs with synthetic drugs up to 2001 13 identified 15 case reports and two case series, involving a total of 19 patients and 21 patients, respectively, together with six analytical investigations, the largest of which was the previously mentioned study in Taiwan 3. From the first entry in 2007 up to March 2017, the United States Food and Drug Administration reported 795 tainted products marketed as dietary supplements, with the main product categories being sexual enhancement (362 entries), weight loss (322 entries) and muscle building (90 entries) 14. Compared with these reports, which were mainly routine surveillance data or case reports/series with a small number of affected patients, the present study, to the authors’ knowledge, is the largest case series that reports an overview of the use of various adulterated pCMs and health products and the resulting adverse effects.

Sibutramine, an anorectic, was the single most common adulterant in our study, while weight reduction was also the most frequently reported indication for the use of these adulterated products. Sibutramine was withdrawn from the market in the United States and many other regions, including Hong Kong, in 2010, owing to its association with increased cardiovascular events and strokes. However, as illustrated in our case series, the ban on this drug did not result in its eradication from illicit slimming products. The danger of this drug was demonstrated in the fatal case in the present series: a 21‐year‐old woman with good previous health developed ventricular fibrillation and cardiac arrest after the use of a slimming product adulterated with sibutramine and N‐desmethyl‐sibutramine for 1 month. The use of slimming products adulterated with sibutramine has also been associated with acute psychosis 8, which was the most common adverse effect encountered in the present study.

Other banned drugs, such as phenolphthalein, fenfluramine, phenformin, phenylbutazone and phenacetin, were also not uncommonly detected in these adulterated pCMs and health products. These drugs were usually withdrawn from the market owing to their higher toxicities – for example, the potential carcinogenicity of phenolphthalein, valvular heart disease and pulmonary hypertension associated with fenfluramine, lactic acidosis associated with phenformin, agranulocytosis associated with phenylbutazone, and the carcinogenicity and nephrotoxicity of phenacetin. Adulteration with banned drugs is therefore a particularly dangerous practice and could lead to potentially fatal adverse effects. As shown in our cases, eight out of 16 cases of fatal or severe outcomes were attributed to various banned drugs.

Drug analogues, for which the chemical structures are substantially similar to those of the original compounds, were also occasionally identified in the present case series. Examples included analogues of anorectics (N‐nitrosofenfluramine, N‐desmethyl‐sibutramine and N‐bisdesmethyl‐sibutramine) and analogues of erectile dysfunction drugs (acetildenafil, aminotadalafil, homosildenafil and chloropretadalafil). These drug analogues, which are not always able to be identified by conventional analytical methods, were probably added to the illicit products in an attempt to evade detection by regulatory authorities. The presumption that these analogues have similar pharmaceutical effects as the original drugs is unproven and, worse still, they may lead to adverse effects that are different or even more severe than those associated with the original compounds. The association of liver failure with N‐nitrosofenfluramine, which has not been seen in fenfluramine, is one typical example 15.

It is not uncommon to find multiple adulterants in a single pCM or health product. One of the severe poisoning cases found in the present study was a 46‐year‐old man who developed secondary adrenal insufficiency, renal impairment and a peptic ulcer after consuming a pCM with 17 adulterants, including prednisone acetate and six NSAIDs, for 10 years. We note that adulteration of products indicated for pain control with corticosteroid and multiple NSAIDs is particularly common. This dangerous practice may lead to significant overdose, and the hazard will be compounded if the patient is taking other adulterated products and prescribed Western medications as well. In the present study, most of the adulterants were added for obvious reasons – mainly to increase the efficacy of the products and occasionally to prevent the adverse effects of other adulterants (e.g. H2‐antihistamines with NSAIDs). Nevertheless, the motive for adding some of the co‐adulterants that were irrelevant to the claimed therapeutic indications remained obscure. Contamination or errors in the manufacturing process is one possible explanation. The outbreak of hypoglycaemia caused by the use of sexual enhancement products adulterated with sildenafil and glibenclamide in 2008 in Hong Kong and Singapore illustrated the danger of these therapeutically irrelevant co‐adulterants 12, 16. This outbreak also contributed to the surge in the total number of cases identified in 2008.

All of the data in the current study originated from cases referred to our laboratory as a result of suspected poisoning or suspicion of adulteration, and hence cannot be extrapolated to represent the exact prevalence of such illicit products in the market. Nevertheless, our data, in a way, reflect a more complete picture of the danger and toxicity of adulterated pCMs or health products that can be obtained from various easily accessible sources, with internet trade being one example that is gaining popularity. To safeguard public health, it is of paramount importance to enhance public awareness of the risk of pCM/health product adulteration and the associated potentially fatal adverse effects. The public should be educated not to consume pCMs and health products from dubious sources. In Hong Kong, citizens who wish to use Chinese medicine are advised to consult a Chinese medicine practitioner or use registered pCMs. Frontline clinicians should have a high index of suspicion. For suspected poisoning cases, a detailed drug history including Chinese medicine and health products, together with a toxicological analysis of biological and drug specimens, can help to confirm the diagnosis.

Conclusions

In the present study, we report 404 cases involving the use of 487 adulterated pCMs or health products, with a total of 1234 adulterants detected. A significant proportion of patients (65.1%) had adverse effects that were attributable to these illicit products, including 14 severe and two fatal cases. Disguised as natural and safe products, these illicit pCMs and health products are clearly hazardous to the public. Intensive health education, as well as effective regulatory control, are important measures to combat this problem.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

Ching, C. K. , Chen, S. P. L. , Lee, H. H. C. , Lam, Y. H. , Ng, S. W. , Chen, M. L. , Tang, M. H. Y. , Chan, S. S. S. , Ng, C. W. Y. , Cheung, J. W. L. , Chan, T. Y. C. , Lau, N. K. C. , Chong, Y. K. , and Mak, T. W. L. (2018) Adulteration of proprietary Chinese medicines and health products with undeclared drugs: experience of a tertiary toxicology laboratory in Hong Kong. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 84: 172–178. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13420.

References

- 1. Thematic household survey report no. 58. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Census and Statistics Department, 2015.

- 2. Traditional Chinese medicine: a report by the committee on traditional Chinese medicine. Singapore: Ministry of Health, 1995.

- 3. Huang WF, Wen KC, Hsiao ML. Adulteration by synthetic therapeutic substances of traditional Chinese medicines in Taiwan. J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 37: 344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koh HL, Woo SO. Chinese proprietary medicine in Singapore: regulatory control of toxic heavy metals and undeclared drugs. Drug Saf 2000; 23: 351–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. da Justa Neves DB, Caldas ED. Dietary supplements: international legal framework and adulteration profiles, and characteristics of products on the Brazilian clandestine market. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2015; 73: 93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Persson HE, Sjoberg GK, Haines JA, Pronczuk de Garbino J. Poisoning severity score. Grading of acute poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 1998; 36: 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SPH, et al The IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucl Acids Res 2016; 44: D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen SP, Tang MH, Ng SW, Poon WT, Chan AY, Mak TW. Psychosis associated with usage of herbal slimming products adulterated with sibutramine: a case series. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2010; 48: 832–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tang MH, Chen SP, Ng SW, Chan AY, Mak TW. Case series on a diversity of illicit weight‐reducing agents: from the well known to the unexpected. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011; 71: 250–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ching CK, Lam YH, Chan AY, Mak TW. Adulteration of herbal antidiabetic products with undeclared pharmaceuticals: a case series in Hong Kong. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 73: 795–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chong YK, Ching CK, Ng SW, Mak TW. Corticosteroid adulteration in proprietary Chinese medicines: a recurring problem. Hong Kong Med J 2015; 21: 411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Poon WT, Lam YH, Lee HH, Ching CK, Chan WT, Chan SS, et al Outbreak of hypoglycaemia: sexual enhancement products containing oral hypoglycaemic agent. Hong Kong Med J 2009; 15: 196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ernst E. Adulteration of Chinese herbal medicines with synthetic drugs: a systematic review. J Intern Med 2002; 252: 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tainted products marketed as dietary supplements_CDER. Food and Drug Administration, United States. 2017. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/sda/sdnavigation.cfm?filter=&sortColumn=1d&sd=tainted_supplements_cder&page=1 (last accessed 21 April 2017).

- 15. Adachi M, Saito H, Kobayashi H, Horie Y, Kato S, Yoshioka M, et al Hepatic injury in 12 patients taking the herbal weight loss AIDS Chaso or Onshido. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 488–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kao SL, Chan CL, Tan B, Lim CC, Dalan R, Gardner D, et al An unusual outbreak of hypoglycaemia. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 734–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]