Abstract

Background:

The treatment of distal clavicle fracture is always a challenge, as it is mostly unstable and has higher rate of delayed union, malunion, non-union and associated acromioclavicular arthritis. So the management of these fractures remains controversial. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the functional results of Type 2 distal end clavicle fractures treated with superior anterior locking plate.

Methods:

From June 2011 to August 2015 a retrospective study of12 male patients (mean age of 41.3 years) 11 with unilateral and 1 with bilateral distal clavicle fractures treated with superior anterior locking plate was done. They were evaluated at regular intervals with mean follow up of 14 months(12-18 months). Those with minimum one year follow up were included in our study. All were evaluated for the functioning of the shoulder joint by both Oxford shoulder score and Quick DASH scores, rate of bone union, complications and earliest time for return to work.

Results:

All fractures union seen within 6-8 weeks (mean time: 7.1 weeks). All had good shoulder range of motion. The average oxford shoulder and Quick DASH score were 46.2 and 6.5. There were no major complications in our study viz. non-union, plate failure, secondary fracture. But one patient had superficial wound infection. All patients returned to work within 3 months of postoperative period.

Conclusion:

Displaced distal clavicle fractures treated with superior anterior locking plates achieved excellent results in terms of bony union with rarely any complications and demonstrate promising results with this novel technique.

Keywords: Arthritis, Clavicle, Fracture, Non-union, Mal-union

Introduction

Clavicle fractures are common due to its subcutaneous position. It accounts for 2-5% of all fractures in adults and 10-15% of all fractures in children (Roughly a quarter – Lateral end) (1, 2). Neer classified these lateral end fractures into three types according to their relation to the coracoclavicular ligaments followed by Rockwood’s subclassification in 1982 (3).

Neer recognised that the type II fractures carry a higher risk of non-union (22-50%) for non-operatively managed fractures (3, 4). The high incidence of non union is due to displacement of two fragments by opposing forces acting on them, mainly, trapezius that displaces the proximal fragment superiorly and the weight of the arm draws the distal fragment inferiorly resulting in major displacement (5).

A prolonged conservative management results in bone resorption, prominent scar and an altered surgical field that further complicates any subsequent surgical intervention (6). Surgical management ranges from joint spanning to joint sparing implants such as K wires, tension band fixation, coracoclavicular screw fixation, distal clavicle excision, osteosynthesis by hook plate or a locking plate fixation each having its own sets of merits and demerits (7-11).

Our study evaluates these fractures treated by superior anterior locking plate meant specifically for the distal clavicle. We analysed the following: a) union rates b) complications c) functional outcome by oxford shoulder score and Quick DASH scoring d) earliest time for return to work.

Materials and Methods

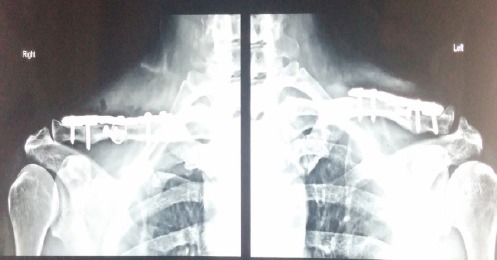

In our retrospective study of 12 male patients, there were 11 unilateral unstable fractures (seven right, four left) and one bilateral fracture (Case 1 [Figure 1 a – e]) treated between June 2011 to August 2015 at our centres. The mean age was 41.3 years (22-54 years). Mode of injury- 1. Nine due to road traffic accidents 2. three due to fall and none had significant associated injuries. At the time of presentation we obtained two radiographic views (AP and Zanca) of the distal clavicle. All patients were taken up for surgery within 10 days of injury. Appropriate consent and approvals were obtained. We had an inclusion and exclusion criteria,

Figure 1a.

49-year-old male with bilateral clavicle fractures (type 2).

Inclusion Criteria- 1. Skeletally mature individuals with Type II fractures within 10 days of injury. 2. Absence of pre-existing sub acromial pathology.

Exclusion Criteria- 1. Type I and Type III fractures 2. Open fractures 3. Type II fractures with comorbidities that would elevate the risk of anaesthesia and surgery 4. nonunion 5. fractures presenting after 10 days of injury 6.skeletal immaturity. 7. Surgical technique other than locking plate.

We did not distinguish Type II fractures into IIA and IIB, as they are clinically equivalent injuries and it is difficult to distinguish them radiologically (12).

Surgical Technique

All procedures were carried out under general anaesthesia after prophylactic antibiotics, with patient in “beach chair” position on operating table. We used the standard anterosuperior approach to the clavicle. The fracture site, acromion were exposed completely. The initial reduction was maintained with K-wires followed by plate fixatation. In few cases we used 2mm mini fragment screws to lag the fracture fragments together. We countersunk the lag screws to avoid prominence and conflicts with plate positioning. In one case wiring was done in the form of cerclage for additional stability. The plate design allowed multiple 2.7 mm locking screws polyaxially in the distal fragment. We used both locking and non locking screws with lag and lock principle in the proximal fragment. The torn coracoclavicular ligament was identified and if found necessary suturing done. We did not use any suture anchors for coracoclavicular augmentation in our fixation techniques. The patient with bilateral clavicular fracture underwent surgery in same sitting. Final screw position was confirmed by C-arm before wound closure. The average surgical time was 40-60 minutes, with an average blood loss of 75-100 ml.

Post op Protocol

Postoperatively, patients were on IV antibiotics for three days. The sutures were removed on the tenth day, and the arms were placed in arm sling for 6weeks. Pendular exercises commenced within the first 24 hours after surgery. Passive flexion and extension was started after suture removal. All patients were referred for physiotherapy and clinicoradiological follow up was done at third week, sixth week, third month, sixth month and one year following surgery.

The functional outcome was evaluated using Oxford shoulder score and Quick DASH scores (13). There are no clavicle trauma scores and hence shoulder outcome scores were used. The Oxford shoulder score which is a questionnaire based subjective assessment of patients’ pain and impairment of activities of daily living. The Quick DASH is shortened version of the DASH outcome score, uses 11 items in the full questionnaire to measure physical function and symptoms in patients with any disorders of the upper limb. Tests were done to identify any associated acromioclavicular joint and rotator cuff pathology. Serial Radiographs were looked for union, implant migration and acromioclavicular pathology. Patients were usually allowed to get back to their normal activity 10-12 weeks following surgery.

Results

All twelve patients returned for clinical and radiological follow up [Table 1]. Average clinical follow up was for 14 months (range, 12-18 months). Radiological assessment was done for bony union and clinical outcome was evaluated by using both shoulder scores at each follow up, which showed gradual improvement in score in each follow up. All fractures united well without any additional procedures like bone grafting, or revised fixations. The mean time for fracture union was 7.1 weeks (range, 6-8 weeks) in all cases.

Table 1.

Clinical outcome by ucla score

| SL. No | Pain | Function | Active forward flexion | Strength of forward flexion | Patients satisfaction | Final score | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 M |

6 M |

1 Y |

3 M |

6 M |

1 Y |

3 M |

6 M |

1 Y |

3 M |

6 M |

1 Y |

3 M |

6 M |

1 Y |

1 Y |

|

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 24 |

| 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 25 |

| 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 30 |

| 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 30 |

| 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 29 |

| 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 32 |

| 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 30 |

| 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 30 |

| 9 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 30 |

| 10 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 29 |

| 11 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 30 |

| 12 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 29 |

The patients were followed up at regular intervals and there was no statistical difference between the functional scores and the range of movements when the scores were compared at three, six, twelve months and the final follow up using Wilcoxon signed rank test (P=0.45). All patients with minimum one year follow up were included in our study showing an average Oxford shoulder score of 46.2 (range 39-48) and Quick DASH score of 6.5 (range 0-13.5) at the end of final follow up.

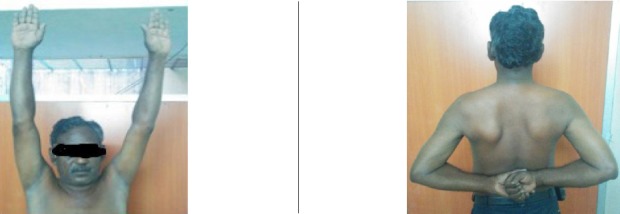

All twelve showed good satisfactory outcome (Case 2 [Figure 2 a – d]) results based on Oxford and Quick DASH scoring system (13). One patient had a superficial wound infection that resolved after oral antibiotics. All patients returned to work within 3 months of post op period (range, 8 – 12 weeks). No implant related complications occurred in our patients during follow up. Four patients underwent metal exit due to prominent hardware after 1 year of surgery.

Figure 1b.

Immediate post op X-rays.

Discussion

Surgical intervention is an indication for displaced Type II distal clavicle fractures (14, 15). The rarity of the fracture, the lack of documentation of the results, poor fixation of the lateral fragment with several surgical techniques, poor acceptance of any single method and the proposed techniques having its proven advantages and disadvantages are the problems encountered.

Transacromial K-wires have high risk of infection, nonunion and a potential risk of wire migration (16). Tension band techniques provide no protection against wire migration and give rise to skin problems which necessitates its removal (17). Bosworth’s Coracoclavicular screw fixation has screw backout and peri-implant fracture as possible complications (8). Coracoclavicular slings though satisfactory, needs extensive dissection to pass the slings below the coracoid process, it has high risk of fatigue fracture of sling, coracoid process and fixation failure (18, 19).

To improve the osteosynthesis of the distal fragment two newer implant designs were used, joint spanning hook plate and joint sparing precontoured locking plates (10, 11). Hook plate achieved excellent union rates but it is not without its complications which include peri-implant fracture, plate’s hook fracture, enlargement of the hook’s hole in the acromion, hook migration with rotator cuff tear, acromial wear, need of plate removal before mobilisation and persistant non-union (10).

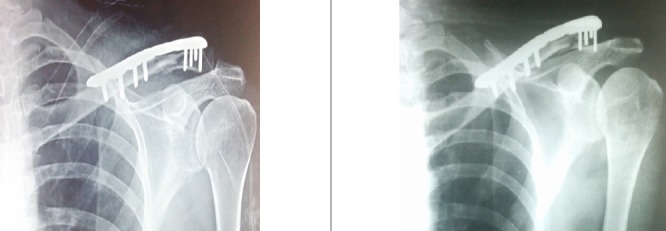

Fixation of fractures of the lateral clavicle with locking plates is relatively a new technique and had proven beneficial in treating fractures with poor bone quality, fractures with short distal segment and distal fractures involving the diaphysis (segmental fractures) [Figure 3]. It is a low profile plate with multiple divergent, fixed angle screws which increases pull out strength in the distal segment which is small and osteopenic. It avoids the need to bridge across the clavicle to the acromion, motion at the acromioclavicular joint is preserved. In our study group of 12, all achieved excellent bony union (100%). We had only one complication of superficial infection (bilateral fracture) and it settled by oral antibiotics.

Figure 1c.

Patient after suture removal.

Our study had number of limitations. The study included only a small group. It was due to low overall incidence of this particular fracture pattern, we didn’t have non operative control group and our results were not compared with other methods of fixation.

Superior anterior locking plate is a low profile implant providing stable fixation of the fracture and there is no need for implant removal prior to mobilisation (20-22).

Displaced distal clavicle fractures (type 2) treated with superior anterior locking plates achieved excellent results in terms of bony union and satisfactory functional outcome with rarely any early complications and demonstrate promising results with this new technique. The number of patients treated by this technique is low but concordant with the incidence of the fracture, inspite the results of our 12 patients are encouraging , we need a longer term follow up with more number of patients as well as further comparative studies are warranted.

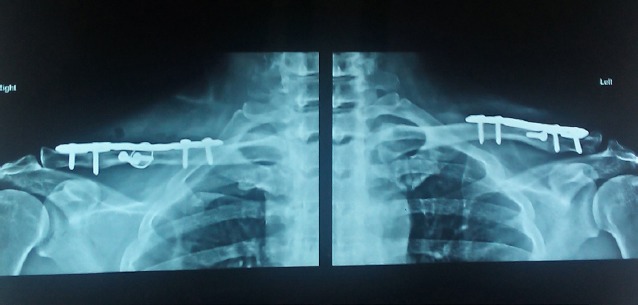

Figure 1d.

Post-operative x-ray after 8 months with good union.

Figure 1e.

Patient had satisfactory functional outcome.

Figure 2a.

35-year-old male patient with left side distal clavicle fracture.

Figure 2c.

Post-op X-ray after 7 months with good union.

Figure 2d.

Patient had satisfactory functional outcome.

Figure 3.

30 yrs male with segmental fracture clavicle with type 1 distal clavicle fracture showing extended indication of locking plate (but this case is not included in our study).

References

- 1.Postacchini F, Gumina S, De Santis P, Albo F. Epidemiology of clavicle fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(5):452–6. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.126613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson CM. Fractures of the clavicle in the adult. Epidemiology and classification. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(3):476–84. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b3.8079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neer CS., 2nd Fractures of the distal third of the clavicle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;58(1):43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritche PK, McCarty EC. Distal clavicle fractures: a current review. Curr Opin Orthop. 2004;15(4):257–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordqvist A, Petersson C, Redlun-Johnell I. The natural course of lateral clavicle fracture 15 (11–21) year follow-up of 110 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64(1):87–91. doi: 10.3109/17453679308994539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson CM, Cairns DA. Primary non operative treatment if displaced lateral fractures of clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(4):778–82. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200404000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jou IM, Chiang EP, Lin CJ, Lin CL, Wang PH, Su WR. Treatment of unstable distal clavicle fracture with Knowles pin. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(3):414–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi H, Arakawa H, Kobayashi M. Results of the Bosworth method for unstable fractures of the distal clavicle. Int Orthop. 1998;22(6):366–8. doi: 10.1007/s002640050279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kay SP, Ellman H, Harris E. Arthroscopic distal clavicle excision. Technique and early results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;301(1):181–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang C, Huang J, Luo Y, Sun H. Comparison of the efficiency of a distal clacicular locking plate versus clavicular hook plate in the treatment of unstable distal clavicle fractures and a systematic literature review. Int Orthop. 2014;38(7):1461–68. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2340-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson JR, Willis MP, Nelson R, Mighell MA. Precontoured superior locked plating of distal clavicle fractures: a new strategy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(12):3344–50. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2009-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rockwood CA. The shoulder. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009:381–445. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith MV, Calfee RP, Baumgarten KM, Brophy RH, Wright RW. Upper extremity-specific measures of disability and outcomes in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(3):277–85. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neer CS., 2nd . Fractures of the clavicle. In: Rockwood CA, Green DP, editors. Fractures in adults. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Co; 1984. pp. 703–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neviaser RJ. Injuries to the clavicle and acromioclavicular joint. Orthop Clin North Am. 1987;18(3):433–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdelnoor J, Mantoura J, Nahas A. Cervicothoracic pin migration following open reduction and pinning of a clavicular fracture: case report. East J Med. 2000, 5(1):26–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badhe SP, Lawrence TM, Clark DI. Tension band suturing for the treatment of displaced type-2 lateral end clavicle fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127(1):25–8. doi: 10.1007/s00402-006-0197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaipel M, Majewski M, Regazzoni P. Double-plate fixation in lateral clavicle fractures-a new strategy. J Trauma. 2010;69(4):896–900. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181bedf28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moneim MS, Balduini FC. Coracoid fracture as a complication of surgical treatment by coracoclavicular tape fixation. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;168(7):133–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen JR, Willis MP, Nelson R, Mighell MA. Precontoured superior locked plating of distal clavicle fractures: a new strategy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(12):3344–50. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2009-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choo SK, Nam JH, Kim Y, Oh HK. The surgical outcome of unstable distal clavicle fractures treated with 2.4 mm volar distal radius locking plate. J Korean Fract Soc. 2015;28(1):38–45. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhatia DN, Page RS. Surgical treatment of lateral clavicle fractures associated with complete coracoclavicular ligament disruption: clinico-radiological outcomes of acromioclavicular joint sparing and spanning implants. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2012;6(4):116. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.106224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]