Abstract

The importance of the gut–brain axis in regulating stress-related responses has long been appreciated. More recently, the microbiota has emerged as a key player in the control of this axis, especially during conditions of stress provoked by real or perceived homeostatic challenge. Diet is one of the most important modifying factors of the microbiota-gut-brain axis. The routes of communication between the microbiota and brain are slowly being unravelled, and include the vagus nerve, gut hormone signaling, the immune system, tryptophan metabolism, and microbial metabolites such as short chain fatty acids. The importance of the early life gut microbiota in shaping later health outcomes also is emerging. Results from preclinical studies indicate that alterations of the early microbial composition by way of antibiotic exposure, lack of breastfeeding, birth by Caesarean section, infection, stress exposure, and other environmental influences - coupled with the influence of host genetics - can result in long-term modulation of stress-related physiology and behaviour. The gut microbiota has been implicated in a variety of stress-related conditions including anxiety, depression and irritable bowel syndrome, although this is largely based on animal studies or correlative analysis in patient populations. Additional research in humans is sorely needed to reveal the relative impact and causal contribution of the microbiome to stress-related disorders. In this regard, the concept of psychobiotics is being developed and refined to encompass methods of targeting the microbiota in order to positively impact mental health outcomes. At the 2016 Neurobiology of Stress Workshop in Newport Beach, CA, a group of experts presented the symposium “The Microbiome: Development, Stress, and Disease”. This report summarizes and builds upon some of the key concepts in that symposium within the context of how microbiota might influence the neurobiology of stress.

1. Introduction

The concept of the gut influencing brain and behaviour, and vice-versa, has perhaps been best appreciated and studied as it relates to the cephalic (preparatory) phase of digestion, visceral pain and malaise, and the ability of emotional stress to disrupt digestive functions. Nonetheless, despite wide integration of the “gut-brain” concept into our everyday vernacular (e.g., gut feelings, gut-wrenching, gut instinct, gutted, gutsy, it takes guts, butterflies in one's stomach), neuroscientists have only recently developed adequate tools with which to reveal the bi-directional links between gut physiology and brain function, and to determine how these links operate under normal and stressful conditions. At the 2016 Neurobiology of Stress Workshop in Newport Beach, CA, a group of experts presented the symposium “The Microbiome: Development, Stress, and Disease”. This report summarizes and expands upon some of the key points from this symposium, focused on current understanding of how microbiota influence the neurobiology of stress.

The complex and multifaceted system of gut-brain communication not only ensures proper maintenance and coordination of gastrointestinal functions to support behaviour and physiological processes, but also permits feedback from the gut to exert profound effects on mood, motivated behaviour, and higher cognitive functions. The linkage between gut functions on the one hand and emotional and cognitive processes on the other is afforded through afferent and efferent neural projection pathways, bi-directional neuroendocrine signaling, immune activation and signaling from gut to brain, altered intestinal permeability, modulation of enteric sensory-motor reflexes, and entero endocrine signaling (Mayer et al., 2014a, Sherwin et al., 2016). Gut microbiota have emerged as a critical component potentially affecting all of these neuro-immuno-endocrine pathways (Carabotti et al., 2015, Bailey, 2014). For example, even short-term exposure to stress can impact the microbiota community profile by altering the relative proportions of the main microbiota phyla (Galley et al., 2014), and experimental alteration of gut microbiota influences stress responsiveness, anxiety-like behaviour, and the set point for activation of the neuroendocrine hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) stress axis (Carabotti et al., 2015, Golubeva et al., 2015, De Palma et al., 2015, Moussaoui et al., 2017, Crumeyrolle-Arias et al., 2014). Disease-related animal models such as mild and chronic social defeat stress also lead to significant shifts in cecal and fecal microbiota composition; these changes are associated with alterations in microbiota-related metabolites and immune signaling pathways suggesting that these systems may be important in stress-related conditions including depression (Bharwani et al., 2016, Aoki-Yoshida et al., 2016).

2. The gut microbiome

Within the past decade it has become clear that the gut microbiota is a key regulator of the gut-brain axis. The gut is home to a diverse array of trillions of microbes, mainly bacteria, but also archaea, yeasts, helminth parasites, viruses, and protozoa (Lankelma et al., 2015, Eckburg et al., 2005, Gaci et al., 2014, Scarpellini et al., 2015, Williamson et al., 2016). The bacterial gut microbiome is largely defined by two dominant phylotypes, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, with Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia phyla present in relatively low abundance (Lankelma et al., 2015, Qin et al., 2010). Although the ratio of microbial to human cells has been recently revised downward (Sender et al., 2016), it is evident that microbial cells outnumber human cells. The total weight of these gut microbes is 1–2 kg, similar to the weight of the human brain (Stilling et al., 2014). Microbiota and their host organisms co-evolved and are mutually co-dependent for survival, and mammals have never existed without microbes, except in laboratory situations (Bordenstein and Theis, 2015).

In humans and other mammals, colonization of the infant gut is thought to largely begin at birth, when delivery through the birth canal exposes the infant to its mother's vaginal microbiota, thereby initiating a critical maternal influence over the offspring's lifelong microbial signature (Backhed et al., 2015, Collado et al., 2012, Donnet-Hughes et al., 2010). Advances in sequencing technologies are revealing that the early developmental microbiota signature influences almost every aspect of the organism's physiology, throughout its life. The role of microbiota composition as a susceptibility factor for various stressful insults, especially at key neurodevelopmental windows, is rapidly emerging (Borre et al., 2014), and there is growing evidence that targeted manipulations of the microbiota might confer protection to the brain to ameliorate the negative effects of stress during vulnerable developmental periods.

3. Gut microbiota and stress-related behaviours

Several lines of evidence support the suggestion that gut microbiota influence stress-related behaviours, including those relevant to anxiety and depression. Work using germ-free (GF) mice (i.e., delivered surgically and raised in sterile isolators with no microbial exposure) demonstrates a link between microbiota and anxiety-like behaviour (Neufeld et al., 2011, Diaz Heijtz et al., 2011, Clarke et al., 2013). In particular, reduced anxiety-like behaviour in GF mice was shown in the light-dark box test and in the elevated plus maze (see (Luczynski et al., 2016a) for review). On the other hand, GF rats display the opposite phenotype, and are characterized by increased anxiety-like behaviour (Crumeyrolle-Arias et al., 2014). Interestingly, the transfer of stress-prone Balb/C microbiota to GF Swiss Webster (SW) mice has been shown to increase anxiety-related behaviour compared to normal SW mice, while transfer of SW microbiota to GF Balb/C mice reduced anxiety-related behaviour compared to normal Balb/C mice suggesting a direct role for microbiota composition in behaviour (Bercik et al., 2011a). Further, monocolonization of GF mice with Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 increased locomotor activity in comparison to control GF mice, a behavioural change that was associated with increased levels of dopamine, serotonin and their metabolites in the striatum (Liu et al., 2016a). Furthermore, antibiotic treatment during adolescence in mice altered microbiota composition and diversity with concomitant reduction in anxiety-like behaviour (Desbonnet et al., 2015). Interestingly, the reduced anxiety-like behaviour was accompanied by cognitive deficits, reduced levels of hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA, and reduced levels of oxytocin and vasopressin in the hypothalamus (Desbonnet et al., 2015).

4. The microbiome and central stress effects

Individual differences in life-long stress responsiveness and susceptibility to stress-related disorders have been linked both to genetic and environmental factors, particularly early-life exposures that can alter the developmental assembly and function of central neural circuits. Intriguingly, it has become increasingly clear that bacteria are required for normal brain development (Neufeld et al., 2011, Diaz Heijtz et al., 2011, Clarke et al., 2013, Bercik et al., 2011a, Hsiao et al., 2013, Stilling et al., 2015) as well as brain function in adulthood. Indeed, key processes associated with neuroplasticity in the adult brain such as neurogenesis (Ogbonnaya et al., 2015) and microglia activation (Erny et al., 2015) have been shown to be regulated by the microbiota. Findings such as these have contributed to a paradigm shift in neuroscience and psychiatry (Mayer et al., 2014b, Cryan and Dinan, 2012), such that the early development and later function of the brain may be modified by targeting the microbiome.

Evidence for a crucial role for the microbiota in regulating stress-related changes in physiology, behaviour and brain function has emerged primarily from animal studies. A very important discovery was made in 2004, when GF mice were found to have an exaggerated HPA axis response to stress, which could be reversed by colonization with a specific Bifidobacteria species (Sudo et al., 2004). Results from subsequent studies have continued to support a connection between gut microbiota and stress responsiveness, including reports that stress exposure early in life or in adulthood can change the organism's microbiota composition, and that microbial populations can shape an organism's stress responsiveness (Golubeva et al., 2015, De Palma et al., 2015, Bharwani et al., 2016, O Mahony et al., 2009, Bailey et al., 2011, Jasarevic et al., 2015). Recently, investigators have used fecal microbiota transplantation approaches to demonstrate that stress-related microbiota composition play a causal role in behavioural changes. In one example, investigators showed that transplanting the microbiota from stressor-exposed conventional mice to GF mice resulted in exaggerated inflammatory responses to Citrobacter rodentium infection (Willing et al., 2011). A link between disease-related microbiota and behaviour was also recently demonstrated, where fecal microbiota transplantation from depressed patients to microbiota-depleted rats increased anhedonia and anxiety-like behaviours (Kelly et al., 2016).

A key question in the field is whether treatments targeting the microbiota-brain axis may have therapeutic benefits in stress-related disorders. To this end, several studies have shown that diets that modify the microbiota, prebiotics, and probiotics can reduced stress-related behaviour and HPA activation. For example, dietary supplementation with the n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), in socially isolated mice reduces anxiety and depressive-like behaviours in male but not female mice (Davis et al., 2016). These behavioural effects were associated with male-specific changes in microbiota composition suggesting that these protective effects were mediated by microbiota (Davis et al., 2016). Similarly, long-term supplementation with eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)/DHA mixture normalized the microbiota profile in rats exposed to early life stress and attenuated stress reactivity (Pusceddu et al., 2015). Prebiotics are non-digestible food ingredients that promote growth of commensal bacteria. Mice exposed to a social disruption stressor displayed increased anxiety-like behaviour and a reduced number of immature neurons in the hippocampus, whereas stressed mice that received human milk oligosaccharides 3'sialyllactose or 6'sialyllactose for 2 weeks prior to stress were protected from stress-related changes in behaviour and CNS effects (Tarr et al., 2015). Interestingly, prebiotic administration of bimuno-galactooligosaccharides (B-GOS) reduced salivary cortisol awakening response in healthy people (Schmidt et al., 2015). The reversal of stress effects by probiotics has also been demonstrated. For example, administration of Lactobacillus helveticus NS8 to Sprague Dawley rats improved stress-induced behaviour deficits and attenuated the stress-induced levels of corticosterone (Liang et al., 2015). Similarly, administration of L. heleveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175 prevented stress-induced changes in neurogenesis, barrier integrity, and stress-reactivity (Ait-Belgnaoui et al., 2012).

As mentioned above, the experimental use of GF mice has been instrumental in revealing the impact of microbiota on early brain development (Luczynski et al., 2016a, Gareau, 2014, Sampson and Mazmanian, 2015). A lack of microbes impacts multiple stress-related neurotransmitter systems, across multiple brain regions. Using a genome-wide transcriptomic approach to compare normal control mice to GF mice, Diaz Heijtz and colleagues demonstrated that the GF condition was accompanied by upregulation of many genes associated with a variety of plasticity and metabolic pathways including synaptic long-term potentiation, steroid hormone metabolism, and cyclic adenosine 5-phosphate-mediated signaling (Diaz Heijtz et al., 2011). The functional consequences of this altered gene expression is evident in many brain regions. For example, GF mice display increased expression of myelin-associated genes within the prefrontal cortex, accompanied by hypermyelination within the same brain region (Hoban et al., 2016). Similar findings have been reported within the prefrontal cortex of mice treated with antibiotics in order to deplete the microbiome in adulthood (Gacias et al., 2016).

Gene expression within the hippocampus also is markedly different in GF mice compared to normal controls. The hippocampus exerts strong control over the HPA stress axis, and GF mice are characterized by markedly increased hippocampal 5-HT concentrations (Clarke et al., 2013), accompanied by decreased 5-HT1A receptor gene expression in the dentate gyrus in female (but not male) GF mice (Neufeld et al., 2011). Intriguingly, other CNS alterations in GF mice also are sex-dependent; e.g., altered expression of BDNF has been documented only in male GF mice (Clarke et al., 2013). BDNF is an important plasticity-related protein that promotes neuronal growth, development and survival, with key roles in learning, memory and mood regulation. BDNF gene expression is lower in the cortex and amygdala in male GF mice compared with controls (Diaz Heijtz et al., 2011), whereas hippocampal BDNF levels in GF mice have been reported to either increase (Neufeld et al., 2011) or decrease (Diaz Heijtz et al., 2011, Clarke et al., 2013, Sudo et al., 2004). Hippocampal neurogenesis also is regulated by the microbiome, such that GF mice exhibit increased neurogenesis in the dorsal hippocampus (Ogbonnaya et al., 2015). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis plays a critical role not only in modulating learning and memory, but also in mediating behavioural responses to stress and antidepressant drugs (O'Leary and Cryan, 2014). Although adult GF mice display modest increases in hippocampal volume, ventral hippocampal pyramidal neurons and dentate granule cells are characterized by reduced dendritic branching, with pyramidal neurons displaying fewer stubby and mushroom spines (Luczynski et al., 2016b). Postweaning microbial colonization of GF mice failed to reverse the changes in adult hippocampal neurogenesis, suggesting that there is a critical pre-weaning developmental window during which the microbiota shapes life-long capacity for hippocampal neurogenesis (Ogbonnaya et al., 2015). Conversely, hippocampal neurogenesis is reduced in normal adult mice after they are exposed to an antibiotic regimen to deplete microbiota, an effect that is reversible by exercise or administration of a probiotic cocktail (Mohle et al., 2016).

The microbiome also affects the structure and function of the amygdala, another key stress-related brain region. The amygdala is critical for emotional learning and social behaviour, and is critical for the gating of behavioural and physiological responses to stressful stimuli, especially those that trigger anxiety and/or fear (Stilling et al., 2015, LeDoux, 2007). Altered amygdalar processes are associated with a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders, ranging from autism spectrum (Schumann and Amaral, 2006, Mosconi et al., 2009) to anxiety disorders (LeDoux, 2007, Janak and Tye, 2015). GF mice (on a SW background) display increased amygdala volume, accompanied by dendritic hypertrophy within the basolateral amygdala (BLA). Accordingly, BLA pyramidal neurons are characterized by increased numbers of thin, stubby and mushroom spines in GF mice compared to normal controls (Luczynski et al., 2016b). RNA sequencing studies have revealed significant differences in differential gene expression, exon usage, and RNA-editing within the amygdala. The amygdala of GF mice displays increased expression of immediate early response genes such as Fos, Fosb, Egr2 and Nr4a1, along with increased signaling of the transcription factor CREB (Stilling et al., 2015). Differential amygdalar expression and recoding of genes involved in neuronal plasticity, metabolism, neurotransmission, and morphology also were identified in GF mice. A significant downregulation of immune system-related genes was noted in GF mice (Stilling et al., 2015), consistent with a reportedly underdeveloped immune and brain microglia systems (Erny et al., 2015). Indeed, the immune system may provide a crucial link for microbiota effects on brain physiology and behaviour, perhaps via the recently discovered lymphatic branches within the central nervous system (Louveau et al., 2015).

Although GF mice have been instrumental in advancing all aspects of microbiome research, including microbiome-to-brain signaling (Luczynski et al., 2016a, Grover and Kashyap, 2014), the experimental GF mice model has many drawbacks that limit its utility for clinical translation (Nguyen et al., 2015, Al-Asmakh and Zadjali, 2015, Arrieta and Finlay, 2014). Nevertheless, GF mice provide a platform on which to explore the role of bacteria on early host development and function (Nguyen et al., 2015, Al-Asmakh and Zadjali, 2015, Faith et al., 2010, Arrieta et al., 2014). Antibiotic treatment is an alternative approach that can bypass the perinatal developmental period. Antiobiotic treatment in adult mice alters BDNF protein levels in both the amygdala and hippocampus (Bercik et al., 2011a). When administered during postnatal development, antibiotics promote visceral hypersensitivity in adult male rats without affecting anxiety, cognitive, immune or stress-related responses (O'Mahony et al., 2014). In this model, visceral hypersensitivity was paralleled by specific changes in the spinal expression of pain-associated genes (transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1, the α-2A adrenergic receptor and cholecystokinin B receptor) (O'Mahony et al., 2014). Conversely, antibiotic depletion of microbiota later in life (i.e., in adolescent mice after weaning) led to reduced anxiety coupled with cognitive deficits measured in adulthood (Desbonnet et al., 2015). Altered tryptophan metabolism also was observed in the same animals, along with significantly reduced BDNF, oxytocin and vasopressin gene expression (Desbonnet et al., 2015). More recently, antibiotic depletion in adult rats reportedly has been reported to have a limited impact on stress, anxiety or HPA axis function, but increases depressive-like behaviours, reduces visceral pain responses, and impairs cognition (Hoban et al., 2016). Together these results highlight the importance of microbiome integrity at key developmental windows.

5. Mechanisms of communication from gut microbiota to brain

The precise role played by the microbiota in gut-brain-gut signaling pathways remains to be elucidated. Hindering our efforts is the limited current state of knowledge regarding the identity and function of the gut's vast and diverse microbial composition. However, advances in the field of metagenomics promise to address this concern (Clarke et al., 2012, Fraher et al., 2012). For example, a recent paper (Matsumoto et al., 2013) examining the role of gut microbiota in cerebral metabolism reports that GF mice have an altered metabolic profile compared to their conventionally colonised counterparts, with 10 of these metabolites thought to be specifically involved in brain function. However, the key question remains: through what mechanisms do the gut microbiota influence the CNS, and vice-versa?

A complex communication network exists between the gut and the CNS, which includes the enteric nervous system (ENS), sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), neuroendocrine signaling pathways, and neuroimmune systems (Grenham et al., 2011). Afferent spinal and vagal sensory neurons carry visceral feedback from the gut to the thoracic and upper lumbar spinal cord and to the nucleus of the solitary tract within the caudal brainstem, engaging polysynaptic inputs to higher brain regions, including the hypothalamus and limbic forebrain. Bi-directional control is provided by descending pre-autonomic neural projections from the cingulate and insular cortices, amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and hypothalamus, all of which are positioned to alter vagal and spinal autonomic outflow to the gut (O'Mahony et al., 2011). Collectively, the microbiota–brain–gut axis is thought to communicate not only via these neural routes, but also via humoral signaling molecules and hormonal components. Together, this intricate network exerts effects which alter both GI and brain function (Mayer et al., 2015, Rhee et al., 2009).

5.1. Neural pathways

The gut is innervated by the ENS, a complex peripheral neural circuit embedded within the gut wall comprising sensory neurons, motor neurons, and interneurons. While the ENS is capable of independently regulating basic gastrointestinal (GI) functions (i.e., motility, mucous secretion, and blood flow), central control of gut functions is provided by vagal and, to a lesser extent, spinal motor inputs that serve to coordinate gut functions with the general homeostatic state of the organism (Mertz, 2003). This central control over the ENS is important for adaptive gut responses during stressful events that signal homeostatic threat to the organism. The vagus nerve has been proposed to serve as the most important neural pathway for bidirectional communication between gut microbes and the brain (Forsythe et al., 2012, Forsythe et al., 2014, Goehler, 2006). For example, an intact vagal nerve appears necessary for several effects induced by two separate probiotic strains in rodents (Perez-Burgos et al., 2014). Specifically, chronic treatment with Lactobacillus rhamnosus (JB-1) led to region-dependent alterations in central GABA receptor expression, accompanied by reduced anxiety- and depression-like behaviour and attenuation of stress-induced corticosterone response; these effects required an intact vagus nerve (Bravo et al., 2011). Similarly, in a colitis model, the anxiolytic effect of Bifidobacterium longum was absent in vagotomised mice (Bercik et al., 2011b). In contrast to effects mediated by probiotics (i.e., microbial supplementation), changes in the microbial ecology as a consequence of antibiotic treatment in mice did not depend on vagal nerve integrity (Bercik et al., 2011a). Thus, additional signaling pathways are likely involved in microbiota–brain–gut communication (Barrett et al., 2012).

In a subset of ENS neurons (i.e., sensory after-hyperpolarization neurons), the probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri was found to increase excitability and the number of action potentials per depolarizing pulse, to decrease calcium-dependent potassium channel opening, and to decrease the slow after-hyperpolarization. Thus, L. reuteri appears to target an ion channel in enteric sensory neurons which may mediate its effects on gut motility and pain perception (Kunze et al., 2009). More recently, the electrophysiological properties of myenteric neurons were found to be altered in GF mice, in which myenteric sensory neurons displayed reduced excitability that was restored after colonization with normal gut microbiota (McVey Neufeld et al., 2013).

5.2. Enteroendocrine signaling

A functional microbiota–neurohumoral relationship is established during early microbial colonization of the gut. A multitude of biologically active peptides are present at numerous locations throughout the brain–gut axis, and have a broad array of functions that include not only gut motility and secretion, but also regulation of emotional affect and stress resilience. Bacterial by-products that come into contact with the gut epithelium are known to stimulate enteroendocrine cells (EECs) to produce several neuropeptides such as peptide YY, neuropeptide Y (NPY), cholecystokinin, glucagon-like peptide-1 and -2, and substance P (Cani et al., 2013, Cani and Knauf, 2016). After their secretion by EECs, these neuropeptides presumably diffuse throughout the lamina propria, which is occupied by a variety of immune cells, en route to the bloodstream and/or local receptor-mediated effects on intrinsic ENS neurons or extrinsic neural innervation (e.g., vagal sensory afferents) (Holzer and Farzi, 2014). However, it still is unknown whether any of these EEC peptides are necessary or sufficient for bidirectional communication between the microbiota and CNS. A different type of potential signaling pathway was revealed more recently (Bohorquez et al., 2015), demonstrating direct paracrine communication between EECs and neurons innervating the small intestine and colon (Bohorquez et al., 2015). This newly-identified neuroepithelial circuit may act as a sensory channel for signaling from luminal gut microbiota to the CNS via the ENS, and vice versa. The physical innervation of sensory EECs suggests the presence of an accurate temporal transfer of sensory signals originating in the gut lumen with a real-time modulatory feedback to EECs.

5.3. Serotonin & tryptophan metabolism

Serotonin [5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] is a biogenic amine that functions as a neurotransmitter within the brain and also within the ENS. Indeed, approximately 95% of 5-HT within the body is produced by gut mucosal enterochromaffin cells and ENS neurons. Peripherally, 5-HT is involved in the regulation of GI secretion, motility (smooth muscle contraction and relaxation), and pain perception (Costedio et al., 2007, McLean et al., 2007), whereas in the brain 5-HT signaling pathways are implicated in regulating mood and cognition (Wrase et al., 2006). Thus, dysfunctional 5-HT signaling may underlie pathological symptoms related to both GI and mood disorders, and may also contribute to the high co-morbidity of these disorders (Folks, 2004). Supporting this idea, drugs that modulate serotonergic neurotransmission, such as tricyclic antidepressants and specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors, also have efficacy for treating irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and other GI disorders (Creed, 2006, Gershon and Tack, 2007). It also recently has been shown that the microbiota can regulate 5-HT synthesis in the gut. Specifically, indigenous spore-forming bacteria from the mouse and human microbiota have been shown to promote 5-HT biosynthesis from colonic enterochromaffin cells (Yano et al., 2015).

Serotonin synthesis is crucially dependent on the availability of tryptophan, an essential amino acid which must be supplied by the diet. Clinical depression is associated with reduced plasma tryptophan concentrations and enhanced enzyme activity (Myint et al., 2007). Interestingly, the early life absence of microbiota in GF mice leads to increased plasma tryptophan concentrations and increased hippocampal levels of 5-HT in adulthood (Clarke et al., 2013). These effects are normalized following the introduction of bacteria to GF mice post-weaning, with the probiotic B. infantis reported to affect tryptophan metabolism (Desbonnet et al., 2008). Therefore, gut microbiota may play a crucial role in tryptophan availability and metabolism to consequently impact central 5-HT concentrations. Although the specific mechanisms underlying this putative modulatory interaction are unknown, they are potentially mediated indirectly through an immune-related mechanism linked to microbial colonization (El Aidy et al., 2012).

5.4. Immune signaling

The immune system plays an important intermediary role in the dynamic equilibrium that exists between the brain and the gut (Bengmark, 2013). The HPA axis, ANS and ENS all directly interact with the immune system (Bateman et al., 1989, Genton and Kudsk, 2003, Hori et al., 1995, Leonard, 2006, Nance and Sanders, 2007), and the gut itself is an important immune organ that provides a vital defensive barrier between externally-derived pathogens and the internal biological environment. Gut-associated lymphoid tissues form the largest immune organ of the human body, comprising more than 70% of the total immune system (Vighi et al., 2008). A direct link between infection and brain function has long been known, mainly through the observation that syphilis and Lyme disease often promote psychiatric symptoms (Biesiada et al., 2012). Research using animal models has clearly demonstrated that infectious microorganisms affect behavioural measures through activation of the immune signaling pathways from body to the brain. For example, the pathogenic bacteria Campylobacter jejuni, when administered to mice at subclinical doses, results in anxiety-like behaviour (Lyte et al., 1998). Peripheral administration of pro-inflammatory cytokines in rodents induces a variety of depressive-like behaviours, including sleep disturbances, reduced appetite, and suppression of exploratory behaviour, collectively referred to as sickness behaviours (Bilbo and Schwarz, 2012). Although gut microbes are known to contribute to the maturation and fortification of the immune response, the molecular basis of these contributions is not yet clear. The immunoregulatory effects of probiotic microorganisms have been proposed to occur through the generation of T regulatory cell populations and the synthesis and secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 (Dinan et al., 2013). In support of this, oral consumption of Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in humans is associated with enhanced IL-10 expression in peripheral blood (Bilbo and Schwarz, 2012). Furthermore, feeding of a commensal bacteria to GF mice promotes Treg production and IL-10 synthesis (Macpherson and Uhr, 2002). Therefore, the balance of gut microbes may closely regulate host inflammatory responses. Disturbances to this microbial balance, particularly in early life (O'Mahony et al., 2009), may promote a chronic inflammatory state that can lead to maladaptive changes in mood and behaviour, including increased responsiveness to stress and increased incidence of stress-related disorders.

6. Stress-related disorders and the microbiome–gut–brain axis

6.1. Major depressive disorder (MDD)

One of the principal mechanisms proposed to underlie a gut-brain link in stress-related disorders is via disrupted gut barrier function commonly known as the “leaky gut” phenomenon (Maes et al., 2009), which is proposed to contribute to MDD. The proposed mechanism of action is that the epithelial barrier of the GI tract becomes compromised as a result of psychological or organic stress, leading to increased intestinal permeability and subsequent translocation of gram-negative bacteria across the mucosal lining to access immune cells and the ENS (Gareau et al., 2008). Bacterial translocation leads to activation of an immune response characterized by increased production of inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 and IFNγ. In mice, pre-treatment with the probiotic L. farciminis attenuates the ability of acute restraint stress to increase intestinal permeability and HPA axis responsivity (Ait-Belgnaoui et al., 2012). In further support of the “leaky gut” hypothesis, serum concentrations of IgM and IgA against LPS of enterobacteria is significantly higher in MDD patients compared to healthy controls (Maes and Leunis, 2008). This would suggest that bacterial translocation from the gut is increased in MDD, and the resulting inflammatory response may contribute to the mood disorder. Currently, however, clinical evidence linking MDD with alterations in the gut microbiota is relatively sparse. Naseribafrouei and colleagues failed to identify any differences in terms of microbial diversity within faecal samples obtained from MDD patients and controls, although the levels of Bacteroidetes were lower in MDD patients (Naseribafrouei et al., 2014). Conversely, Jiang and colleagues reported increased diversity (using the Shannon index) in the composition of faecal sample microbiota in MDD patients compared to healthy controls, including increased diversity in the Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria (which include the LPS-expressing Enterobacteriaceae) phyla, countered by a concomitant reduction in the diversity of Firmicutes (Jiang et al., 2015). The basis for conflicting results between these two studies is unclear, but may stem from the different control groups that were used (i.e., outpatients from a neurological unit versus healthy control subjects). More recently, a decreased gut microbial richness and diversity was observed in depressed patients (Kelly et al., 1016).

Animal models have improved our understanding of how the gut microbiota may influence stress-related disorders, including depressive-like behaviours. Maternal separation is frequently used as a model of early life stress that provokes an adult depressive and anxiety-like phenotype, along with alterations in monoamine turnover, immune function and HPA axis activation (O Mahony et al., 2009, O Mahony et al., 2011, Desbonnet et al., 2010). Early work from Bailey and Coe demonstrated that maternal separation decreased faecal Lactobacillus in rhesus monkeys 3 days post-separation (Bailey and Coe, 1999). In rodents, early life maternal separation disrupts the offspring's microbiota and promotes colonic hypersensitivity (O Mahony et al., 2009, O Mahony et al., 2011). More recent work by De Palma and colleagues has elaborated upon the role of the gut bacterial commensals in the development of behavioural despair using the maternal separation model (De Palma et al., 2015). In their study, a developmental history of maternal separation was associated with increased circulating corticosterone in adult GF mice, but not depressive- or anxiety-like behaviours. Thus, the presence of gut microbiota may be unnecessary for the ability of early life maternal separation to alter stress-related HPA axis activity, but may be necessary to alter the development of anxiety- and depressive-like behaviours.

Other animal models of chronic stress/depression have been shown to induce alterations in the microbiota. In rodents, olfactory bulbectomy produces an array of physiological and behavioural symptoms with features similar to MDD, including altered neuroendocrine and neuroimmune responses. The model also has strong predictive validity, as the depressive-like behaviours are normalized only after long-term treatment with antidepressant drugs (Harkin et al., 1999). Interestingly, Park and colleagues demonstrated that bulbectomy affects gut transit and the composition of the microbiota by redistributing the relative abundances of bacterial phyla (Park et al., 2013). While these findings are intriguing, it is difficult to extrapolate how an altered composition of the gut microbiota in bulbectomized animals might relate to clinical depression, or even to other animal models of depression (Dinan and Cryan, 2013). For example, social defeat stress profoundly alters the operational taxonomic units of the gut microbiota, associated with deficits in sociability. A reduction in diversity was associated with decreases in the abundance of Clostridium species, as well as decreases in fatty acid production and biosynthesis pathways leading to dopamine and 5-HT production (Bharwani et al., 2016). This decrease in Clostridium abundance following social defeat stress is in contrast to previous work from Bailey and colleagues, who demonstrated an increase in the relative abundance of Clostridium species following social disruption stress (Bailey et al., 2011). Despite their considerable differences in experimental approach, these animal studies collectively highlight an association between altered gut microbiota and depressive-like behaviour.

While clinical studies have not yet assessed whether probiotics or prebiotics are successful in the treatment of MDD, several groups have documented the beneficial effects of probiotics and prebiotics in healthy individuals (see Table 1). Indeed, the idea that Lactobacillus strains may improve quality of life and mental health is not new. Dr. George Porter Phillips first reported in 1910 that a gelatin-whey formula with live lactic acid bacteria improved depressive symptoms in adults with melancholia (Philips, 1910). More recently, 3-week supplementation with the prebiotic B-GOS was found to decrease the cortisol awakening response and to increase attentional vigilance towards positive stimuli (Schmidt et al., 2015). This finding is consistent with those of a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study, which demonstrated that long-term administration of a probiotic mixture of various Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species resulted in reduced neural activity within a widely distributed brain network in response to a task probing attention towards negative stimuli (Tillisch et al., 2013). A recent study by Steenbergen and colleagues further demonstrated the beneficial effects of a Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium mixed probiotic on mood in healthy individuals (Steenbergen et al., 2015). Moreover, clinical data from healthy participants suggest that probiotics are also effective in alleviating behavioural symptoms of anxiety (Messaoudi et al., 2011a). While the reported effects of prebiotics and probiotics to improve mood in healthy individuals lends support to their use in treating depression and anxiety, carefully controlled clinical trials will be necessary to fully determine their efficacy in treating depression and anxiety.

Table 1.

Clinical and preclinical evidence for the antidepressant and anxiolytic properties associated with targeting the gut microbiota (modified from reference (Sherwin et al., 2016)).

| Behavioural outcomes | Physiological outcomes | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical evidence | |||

| B-GOS | Increased cognitive processing of positive versus negative attentional vigilance | Reduced cortisol awakening response | (Schmidt et al., 2015) |

| Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota | Reduced anxiety scores in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome | Increased numbers of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in faecal samples | (Rao et al., 2009) |

| Improved mood in individuals with a low mood prior to taking the probiotic | NA | (Benton et al., 2007) | |

| Probiotic formulation: Lactobacillus helveticus and Bifidobacterium longum | Reduced psychological distress as measured by the HADS | Reduced 24-h UFC levels | (Messaoudi et al., 2011a) |

| Multispecies probiotic formulation: Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species | Reduced cognitive processing of sad mood; decreased aggressive feelings and rumination | NA | (Steenbergen et al., 2015) |

| Preclinical evidence | |||

| Prebiotic- FOS and GOS | Antidepressant and anxiolytic-like effects in adult mice. Reversed the behavioural effects of chronic psychosocial stress in mice. | Increased BDNF, NR1 and NR2A mRNA, and protein expression in the dentate gyrus and frontal cortex Reduced acute and chronic stress-induced corticosterone release. Modified specific gene expression in the hippocampus and hypothalamus. Reduced chronic stress-induced elevations in pro-inflammatory cytokines levels |

(Savignac et al., 2013; Burokas et al., 2017) |

| Prebiotic- 3′Sialyllactose and 6'sialyllactose |

Anxiolytic effect in mice exposed to SDR |

Prevented SDR-mediated reduction in the number of immature neurons |

(Tarr et al., 2015) |

|

Prebiotic- GOS & polydextrose with lactoferrin (Lf) and milk fat globule membrane Bifidobacterium infantis |

Reduced immobility time of maternally separated rats in a forced swim test | Improves NREM Sleep, Enhance REM Sleep Rebound and Attenuate the Stress-Induced Decrease in Diurnal Temperature Attenuated exaggerated IL-6 response in maternally separated rats following concanavalin A stimulation |

(Thompson et al., 2016) (Desbonnet et al., 2010) |

| Bifidobacterium breve | Improved depressive and anxiety-related behaviours in mice | No effect upon circulating corticosterone | (Savignac et al., 2014) |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Anxiolytic effect in step-down inhibitory avoidance | Anxiolytic effect mediated via the vagus nerve | (Bercik et al., 2011b) |

| Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 | Reduced immobility time and increased sucrose preference in ELS mice | Decreased basal and stress-induced circulating corticosterone levels; attenuated circulating TNF-α and IL-6 levels while increasing IL-10 levels in ELS mice | (Liu et al., 2016b) |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Reduced immobility time in the forced swim test Decreased stress-induced anxiety-like behaviour |

Decreased stress-induced circulating corticosterone secretion and altered central GABA receptor subunit expression Attenuated chronic stress-related activation of dendritic cells while increasing IL-10 + regulatory T cells |

(Bravo et al., 2011) (Bharwani et al., 2017) |

| Lactobacillus fermentum NS9 | Reduced ampicillin-induced anxiety behaviour | Decreased ampicillin-induced corticosterone secretion and increased hippocampal mineralocorticoid receptor and NMDA receptor levels | (Wang et al., 2015) |

| Butyric acid | Reduced immobility time in Flinders sensitive line rats exposed to a forced swim test | Increased BDNF expression within the prefrontal cortex | (Wei et al., 2014) |

Abbreviations used in Table 1. BDNF brain-derived neurotrophic factor, ELS early life stress–exposed, FOS fructo-oligosaccharide, GABA γ-aminobutyric acid, GOS galacto-oligosaccharide, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, IL interleukin, mRNA messenger RNA, NA not assessed, NMDA N-methyl-d-aspartate, SDR social disruption stress, TNF tumour necrosis factor, UFC urinary free cortisol, NR NMDA Receptor.

6.2. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Stress, including early life stress, is a key risk factor for IBS, the most common functional gastrointestinal disorder (Moloney et al., 2016). IBS is considered to reflect pathologically altered gut-brain axis homeostasis. This disorder is associated with abdominal visceral pain and altered bowel habits, and is strongly comorbid with anxiety and depression. Various animal models of visceral hypersensitivity have been exploited to determine the involvement of gut microbiota on visceral pain pathways (Larauche et al., 2012, Moloney et al., 2015). Assessing visceral sensitivity most often occurs with the use of a balloon inflated to specific pressures using a barostat (O Mahony et al., 2012, Ness and Gebhart, 1988). Many of the preclinical models of increased visceral pain are induced by applying a psychological or physical stressor that relate to factors known to predispose to IBS, a clinical disorder characterized by visceral hypersensitivity to pain (Mayer et al., 2001). Early life stress or chronic stress later in life are thought to potentiate visceral pain responses and associated co-morbidities (Moloney et al., 2016). Antibiotics administered early in life have been shown to induce long-lasting effects on visceral pain responses, coupled with alterations in pain signaling pathways (O'Mahony et al., 2014). Results from animal studies of antibiotic-induced dysbiosis demonstrate that microbiota influence the wiring of pain pathways early in development, and that visceral hypersensitivity can persist into adulthood despite later microbial normalization (O'Mahony et al., 2014).

Disturbance of the gut microbiota in adult mice also induces local changes in immune responses and enhanced visceral pain signaling (Verdu et al., 2006). Studies using GF mice before and after bacterial colonization indicate that commensal intestinal microbiota are necessary for the normal excitability of gut sensory neurons (McVey Neufeld et al., 2013). Furthermore, live luminal Lactobacillus reuteri (DSM 17938) reduced jejunal spinal nerve firing evoked by distension or capsaicin (Perez-Burgos et al., 2015). It has also recently been shown that IBS-like abnormal gut fermentation and visceral hypersensitivity can be induced in rats after transplantation of fecal microbiota from constipation-predominant IBS patients (Crouzet et al., 2013).

The gut microbiota has emerged as an important factor that potentially contributes to the pathophysiology of IBS (De Palma et al., 2014, Hyland et al., 2014), despite conflicting evidence regarding the organisation and function of the gut microbiota in both adult and paediatric patients. In this regard, prolonged exposure of mice to a high fat diet (HFD) induces low-grade chronic intestinal inflammation, changes the microbiota composition, and increases bacterial translocation across the intestinal mucosal barrier (Sun et al., 2016, Gulhane et al., 2016). Further, diets high in saturated fat are a risk factor for the development of human inflammatory bowel diseases, including IBS. Exposure to stress impacts colonic motor activity, which can alter gut microbiota profiles, including lower numbers of potentially beneficial Lactobacillus (Lutgendorff et al., 2008). Thus, stress may interact with diet to contribute to IBS. Several studies comparing normal controls to IBS patients have reported decreased proportions of the genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium with increased ratios of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes at the phylum level (Nagel et al., 2016, Rajilic-Stojanovic et al., 2011) (for review see (Rajilic-Stojanovic et al., 2015)). One study indicates that subtypes of IBS patients cluster with regard to changes in diversity and Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratios compared to healthy controls (Jeffery et al., 2012). This study is particularly interesting, as it highlights evidence that subtypes of IBS patients have a relatively “normal” microbiota phenotype while others display either decreased or increased diversity. Those with the “normal” microbiota were more likely to display comorbid depression, which also was associated with deceased intestinal transit time. This subtype clustering may also be linked to differential responses to microbiota manipulation. For example, one study reported that individuals suffering from anxiety and depression showed improvement of these symptoms after consumption of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria, whereas other studies reported a lack of improvement after similar probiotic treatment (Mayer et al., 2014a, Benton et al., 2007). In a recent systematic review of specified probiotics in the management of IBS and other lower gastrointestinal disorders, an overall beneficial effect of probiotics was evident in terms of reduced abdominal pain, bloating, and/or distension in a subset of patients (Hungin et al., 2013). However, results from clinical trials testing probiotics in IBS remain difficult to compare, due to widespread differences in study design, probiotic dose, and probiotic strain (Clarke et al., 2012). Interestingly there has been some success with the gastrointestinal selective antibiotic rifaxamin in treating IBS (Pimentel et al., 2011). Future studies should also focus on the relationship between rifaxamin-induced changes in microbiota and stress responses.

7. High-fat diet, stress, and the gut microbiome

As reviewed in previous sections of this article, the gut-brain axis exerts a substantial physiological impact on mood, behaviour, and stress responsiveness. Acute and chronic exposure to stress can alter both the quality and quantity of calories consumed, and stress-induced alterations in food intake and energy balance can interact with emotional state (Epel et al., 2001). In particular, ingestion of foods rich in fat has been reported to modulate emotional states in humans and animal models (Ulrich-Lai et al., 2015). Using the diet-induced obesity (DIO) animal model, Sharma and Fulton demonstrated that adult C57Bl6 mice consuming a diet containing 58% of calories as trans-fat for 12 weeks develop depressive-like behaviours, including increased immobility in the forced swim task and reduced time spent in open areas of the elevated-plus maze and open field tests (Sharma and Fulton, 2013). These behavioural indices of despair and anxiety were accompanied by elevated basal HPA activity and increased corticosterone secretion in response to stress (Wu et al., 2013).

A role for gut microbiota in the long-known link between diet and emotion has emerged over the past few years, including evidence that high-fat diet feeding promotes a “leaky gut” (i.e., increased intestinal permeability (Cani et al., 2008, Hildebrandt et al., 2009, Kim et al., 2012)), similar to the effect of chronic stress alone (Gareau et al., 2008, Maes and Leunis, 2008, Ait-Belgnaoui et al., 2014), and the combination of high-fat diet and stress exposure may promote even greater bacterial translocation. In mice, chronic stress combined with a diet high in fat and sugar has been reported to exacerbate changes in intestinal tight junction proteins that were associated with altered behaviours and altered inflammatory markers within the hippocampus, with the hippocampal and behavioural effects shown to be diet-dependent (de Sousa Rodrigues et al., 2017). A direct link between high-fat diet, gut microbiota, and behaviour was demonstrated in a recent study in which microbiota from high-fat fed donor mice were transferred to chow-fed recipients whose own microbiota had been depleted by antibiotic treatment (Bruce-Keller et al., 2015). Intriguingly, transfer of the high-fat-related donor microbiota led to increased intestinal permeability and inflammatory markers in the chow-fed recipient mice, accompanied by anxiety-like behaviours (Bruce-Keller et al., 2015). These results are consistent with a large literature supporting the view that increased circulating cytokines subsequent to bacterial translocation can sensitize the HPA axis to stress-induced activation, and also can increase anxiety- and depressive-like behaviours (Keightley et al., 2015, Smythies and Smythies, 2014, Luna and Foster, 2015, Maes et al., 2013). Conversely, probiotic treatment in mice was found to be sufficient to prevent the ability of chronic stress to increase intestinal permeability, and also was sufficient to reduce stress-induced sympathetic outflow and HPA axis activation (Ait-Belgnaoui et al., 2014). Interestingly, however, high-fat diet exposure does not always exacerbate the deleterious effects of stress (Ulrich-Lai et al., 2015). Indeed, one study using mice found that high fat diet ameliorated the ability of chronic social stress to increase anxiety- and depressive-like behaviours; in other words, high fat diet had a selective “protective effect” (Finger et al., 2011). These results emphasize the complex influence of dietary factors on stress-related outcomes, and highlight the need for additional research to unravel complex interactions and causal relationships among diet, stress exposure, and the microbial gut-brain axis.

8. Future directions

The concept of psychobiotics, bacteria with positive effects on mental health, was coined in 2013 (Dinan et al., 2013) and has recently been expanded to include other microbiota-targeted interventions that can positively modify mental health including in healthy volunteers (Sarkar et al., 2016). Animal studies have led the way in showing that specific strains of Bifidobacteria, Lactobacillus or Bacteroides can have positive effects on brain and behaviour (Hsiao et al., 2013, Bravo et al., 2011, Bercik et al., 2011b, Savignac et al., 2014, Savignac et al., 2015), including evidence that certain bacteria can enhance cognitive processes and affect emotional learning (Liang et al., 2015, Gareau, 2014, Bravo et al., 2011, Savignac et al., 2015, Distrutti et al., 2014). However, results from these studies are only slowly being translated to humans, primarily through research using healthy volunteers (Tillisch et al., 2013, Steenbergen et al., 2015, Messaoudi et al., 2011a, Messaoudi et al., 2011b, Kato-Kataoka et al., 2016). Indeed, recent studies have highlighted the difficulties of translating such responses even within the same laboratory. Bifidobacterium longum 1714 is a bacterium with positive anti-stress and pro-cognitive effects in an anxious mouse strain (Savignac et al., 2014, Savignac et al., 2015). Ingestion of this potential psychobiotic by healthy male volunteers was able to attenuate the increases in cortisol output and subjective anxiety in response to the socially evaluated cold pressor test. Furthermore, daily reported stress was reduced by psychobiotic consumption. Finally subtle improvements in hippocampus-dependent visuospatial memory performance, as well as enhanced frontal midline electroencephalographic mobility were observed following the consumption of Bifidobacteria (Allen et al., 2016). On the other hand, while Lactobacillus rhamnosus (JB-1) has one of the strongest preclinical profiles of any potential psychobiotic (Bravo et al., 2011), it had no discernible effect when tested in a similar battery of human stress and neuropsychology tests as the Bifidobacterium longum (Kelly et al., 1016).

Over the next few years it is hoped that the mechanisms underpinning the beneficial effects of specific bacterial strains will be elucidated. Improved understanding of the developmental impact of microbiota perturbations on behaviours relevant to stress and cognitive-related disorders is sorely needed (Desbonnet et al., 2014, Foster and McVey Neufeld, 2013). Finally, a greater investment in large-scale clinical trials is needed to determine whether psychobiotic-based interventions have efficacy in stress-related disorders. Moreover, the relationship between diet and the microbiota-gut-brain axis is ripe for exploitation to develop therapeutic strategies for treating stress-related disorders (See Fig. 1).

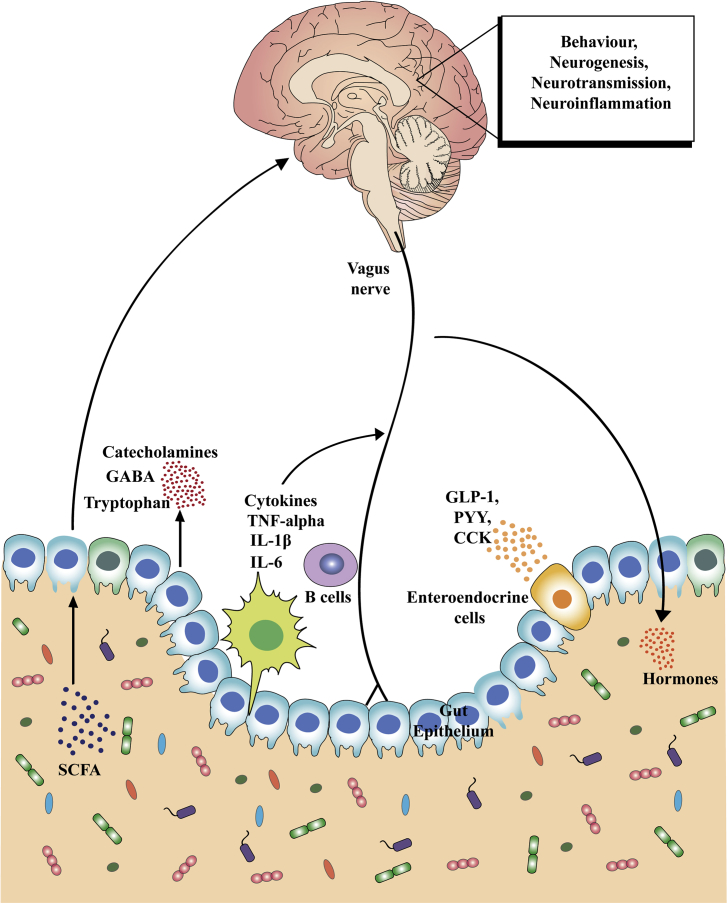

Fig. 1.

Key communication pathways of the microbiota–gut–brain axis. There are numerous mechanisms through which the gut microbiota can signal to the brain. These include activation of the vagus nerve, production of microbial antigens that recruit immune B cell responses, production of microbial metabolites (i.e. short-chain fatty acids [SCFAs]), and enteroendocrine signaling from gut epithelial cells (e.g., I-cells that release CCK, and L-cells that release GLP-1, PYY and other peptides). Through these routes of communication, the microbiota–gut–brain axis controls central physiological processes, such as neurotransmission, neurogenesis, neuroinflammation and neuroendocrine signaling that are all implicated in stress-related responses. Dysregulation of the gut microbiota subsequently leads to alterations in all of these central processes and potentially contributes to stress-related disorders.

5-HT serotonin, CCK cholecystokinin, GABA γ-aminobutyric acid, GLP glucagon-like peptide, IL interleukin, PYY peptide YY, TNF tumour necrosis factor.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kieran Rea for Editorial assistance and Dr. Kiran Sandhu for drawing Fig. 1. Support provided by Ontario Brain Institute and NSERC - RGPIN-312435-12 (JAF), and by the National Institutes of Health grant numbers MH059911 and DK100685 (LR). JFC is supported by Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) [Grant Numbers 07/CE/B1368 and 12/RC/2273]; the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine; JPI ERA-HDHL Transnational Call “Biomarkers for Nutrition and Health” Grant - HEALTHMARK; JPI HDHL “Nutrition & Cognitive Function” Grant - AMBROSIAC. JFC also receives research funding from 4D-Pharma, Mead Johnson, Suntory Wellness, Nutricia and Cremo and has been an invited speaker at meetings organized by Mead Johnson, Yakult, Alkermes and Janssen.

References

- Ait-Belgnaoui A., Durand H., Cartier C., Chaumaz G., Eutamene H., Ferrier L., Houdeau E., Fioramonti J., Bueno L., Theodorou V. Prevention of gut leakiness by a probiotic treatment leads to attenuated HPA response to an acute psychological stress in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:1885–1895. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Belgnaoui A., Colom A., Braniste V., Ramalho L., Marrot A., Cartier C., Houdeau E., Theodorou V., Tompkins T. Probiotic gut effect prevents the chronic psychological stress-induced brain activity abnormality in mice, Neurogastroenterology and motility. Official J. Eur. Gastrointest. Motil. Soc. 2014;26:510–520. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Asmakh M., Zadjali F. Use of germ-free animal models in microbiota-related research. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;25:1583–1588. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1501.01039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen A.P., Hutch W., Borre Y.E., Kennedy P.J., Temko A., Boylan G., Murphy E., Cryan J.F., Dinan T.G., Clarke G. Bifidobacterium longum 1714 as a translational psychobiotic: modulation of stress, electrophysiology and neurocognition in healthy volunteers. Transl. Psychiatry. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.191. e939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki-Yoshida A., Aoki R., Moriya N., Goto T., Kubota Y., Toyoda A., Takayama Y., Suzuki C. Omics studies of the murine intestinal ecosystem exposed to subchronic and mild social defeat stress. J. Proteome Res. 2016;15:3126–3138. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta M.C., Finlay B. The intestinal microbiota and allergic asthma. J. Infect. 2014;69(Suppl. 1):S53–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta M.C., Stiemsma L.T., Amenyogbe N., Brown E.M., Finlay B. The intestinal microbiome in early life: health and disease. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:427. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F., Roswall J., Peng Y., Feng Q., Jia H., Kovatcheva-Datchary P., Li Y., Xia Y., Xie H., Zhong H., Khan M.T., Zhang J., Li J., Xiao L., Al-Aama J., Zhang D., Lee Y.S., Kotowska D., Colding C., Tremaroli V., Yin Y., Bergman S., Xu X., Madsen L., Kristiansen K., Dahlgren J., Wang J. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey M.T. Influence of stressor-induced nervous system activation on the intestinal microbiota and the importance for immunomodulation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014;817:255–276. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey M.T., Coe C.L. Maternal separation disrupts the integrity of the intestinal microflora in infant rhesus monkeys. Dev. Psychobiol. 1999;35:146–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey M.T., Dowd S.E., Galley J.D., Hufnagle A.R., Allen R.G., Lyte M. Exposure to a social stressor alters the structure of the intestinal microbiota: implications for stressor-induced immunomodulation. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2011;25:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett E., Ross R.P., O'Toole P.W., Fitzgerald G.F., Stanton C. gamma-Aminobutyric acid production by culturable bacteria from the human intestine. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012;113:411–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Singh A., Kral T., Solomon S. The immune-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Endocr. Rev. 1989;10:92–112. doi: 10.1210/edrv-10-1-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengmark S. Gut microbiota, immune development and function. Pharmacol. Res. 2013;69:87–113. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton D., Williams C., Brown A. Impact of consuming a milk drink containing a probiotic on mood and cognition. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;61:355–361. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercik P., Denou E., Collins J., Jackson W., Lu J., Jury J., Deng Y., Blennerhassett P., Macri J., McCoy K.D., Verdu E.F., Collins S.M. The intestinal microbiota affect central levels of brain-derived neurotropic factor and behavior in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:e591–593. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.052. 599-609, 609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercik P., Park A.J., Sinclair D., Khoshdel A., Lu J., Huang X., Deng Y., Blennerhassett P.A., Fahnestock M., Moine D., Berger B., Huizinga J.D., Kunze W., McLean P.G., Bergonzelli G.E., Collins S.M., Verdu E.F. The anxiolytic effect of Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 involves vagal pathways for gut-brain communication. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. official J. Eur. Gastrointest. Motil. Soc. 2011;23:1132–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharwani A., Mian M.F., Foster J.A., Surette M.G., Bienenstock J., Forsythe P. Structural & functional consequences of chronic psychosocial stress on the microbiome & host. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;63:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharwani A., Mian M.F., Surette M.G., Bienenstock J., Forsythe P. Oral treatment with Lactobacillus rhamnosus attenuates behavioural deficits and immune changes in chronic social stress. BMC Med. 2017;15:7. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0771-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesiada G., Czepiel J., Ptak-Belowska A., Targosz A., Krzysiek-Maczka G., Strzalka M., Konturek S.J., Brzozowski T., Mach T. Expression and release of leptin and proinflammatory cytokines in patients with ulcerative colitis and infectious diarrhea. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2012;63:471–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbo S.D., Schwarz J.M. The immune system and developmental programming of brain and behavior. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33:267–286. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohorquez D.V., Shahid R.A., Erdmann A., Kreger A.M., Wang Y., Calakos N., Wang F., Liddle R.A. Neuroepithelial circuit formed by innervation of sensory enteroendocrine cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2015;125:782–786. doi: 10.1172/JCI78361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordenstein S.R., Theis K.R. Host biology in light of the microbiome: ten principles of holobionts and hologenomes. PLoS Biol. 2015;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002226. e1002226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borre Y.E., O'Keeffe G.W., Clarke G., Stanton C., Dinan T.G., Cryan J.F. Microbiota and neurodevelopmental windows: implications for brain disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 2014;20:509–518. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo J.A., Forsythe P., Chew M.V., Escaravage E., Savignac H.M., Dinan T.G., Bienenstock J., Cryan J.F. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:16050–16055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller A.J., Salbaum J.M., Luo M., Blanchard E.t., Taylor C.M., Welsh D.A., Berthoud H.R. Obese-type gut microbiota induce neurobehavioral changes in the absence of obesity. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;77:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burokas A., Arboleya S., Moloney R.D., Peterson V.L., Murphy K., Clarke G., Stanton C., Dinan T.G., Cryan J.F. Targeting the microbiota-gut-brain Axis: prebiotics have anxiolytic and antidepressant-like effects and reverse the impact of chronic stress in mice. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.12.031. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P.D., Knauf C. How gut microbes talk to organs: the role of endocrine and nervous routes. Mol. Metab. 2016;5:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P.D., Bibiloni R., Knauf C., Waget A., Neyrinck A.M., Delzenne N.M., Burcelin R. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57:1470–1481. doi: 10.2337/db07-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P.D., Everard A., Duparc T. Gut microbiota, enteroendocrine functions and metabolism. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013;13:935–940. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabotti M., Scirocco A., Maselli M.A., Severi C. The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015;28:203–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G., Cryan J.F., Dinan T.G., Quigley E.M. Review article: probiotics for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome–focus on lactic acid bacteria. Alimentary Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;35:403–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G., Grenham S., Scully P., Fitzgerald P., Moloney R.D., Shanahan F., Dinan T.G., Cryan J.F. The microbiome-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Mol. Psychiatr. 2013;18:666–673. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado M.C., Cernada M., Bauerl C., Vento M., Perez-Martinez G. Microbial ecology and host-microbiota interactions during early life stages. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:352–365. doi: 10.4161/gmic.21215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costedio M.M., Hyman N., Mawe G.M. Serotonin and its role in colonic function and in gastrointestinal disorders. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2007;50:376–388. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0763-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed F. How do SSRIs help patients with irritable bowel syndrome? Gut. 2006;55:1065–1067. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.086348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouzet L., Gaultier E., Del'Homme C., Cartier C., Delmas E., Dapoigny M., Fioramonti J., Bernalier-Donadille A. The hypersensitivity to colonic distension of IBS patients can be transferred to rats through their fecal microbiota. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2013;25:e272–282. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumeyrolle-Arias M., Jaglin M., Bruneau A., Vancassel S., Cardona A., Dauge V., Naudon L., Rabot S. Absence of the gut microbiota enhances anxiety-like behavior and neuroendocrine response to acute stress in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;42:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan J.F., Dinan T.G. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour, Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2012;13:701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D.J., Hecht P.M., Jasarevic E., Beversdorf D.Q., Will M.J., Fritsche K., Gillespie C.H. Sex-specific effects of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) on the microbiome and behavior of socially-isolated mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017 Jan;59:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma G., Collins S.M., Bercik P., Verdu E.F. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in gastrointestinal disorders: stressed bugs, stressed brain or both? J. Physiology. 2014;592:2989–2997. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.273995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma G., Blennerhassett P., Lu J., Deng Y., Park A.J., Green W., Denou E., Silva M.A., Santacruz A., Sanz Y., Surette M.G., Verdu E.F., Collins S.M., Bercik P. Microbiota and host determinants of behavioural phenotype in maternally separated mice. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7735. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa Rodrigues M.E., Bekhbat M., Houser M.C., Chang J., Walker D.I., Jones D.P., Oller do Nascimento C.M., Barnum C.J., Tansey M.G. Chronic psychological stress and high-fat high-fructose diet disrupt metabolic and inflammatory gene networks in the brain, liver, and gut and promote behavioral deficits in mice. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2017;59:158–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbonnet L., Garrett L., Clarke G., Bienenstock J., Dinan T.G. The probiotic Bifidobacteria infantis: an assessment of potential antidepressant properties in the rat. J. Psychiatric Res. 2008;43:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbonnet L., Garrett L., Clarke G., Kiely B., Cryan J.F., Dinan T.G. Effects of the probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis in the maternal separation model of depression. Neuroscience. 2010;170:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbonnet L., Clarke G., Shanahan F., Dinan T.G., Cryan J.F. Microbiota is essential for social development in the mouse. Mol. Psychiatr. 2014;19:146–148. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbonnet L., Clarke G., Traplin A., O'Sullivan O., Crispie F., Moloney R.D., Cotter P.D., Dinan T.G., Cryan J.F. Gut microbiota depletion from early adolescence in mice: implications for brain and behaviour. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2015;48:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Heijtz R., Wang S., Anuar F., Qian Y., Bjorkholm B., Samuelsson A., Hibberd M.L., Forssberg H., Pettersson S. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:3047–3052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan T.G., Cryan J.F. Melancholic microbes: a link between gut microbiota and depression? Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2013;25:713–719. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan T.G., Stanton C., Cryan J.F. Psychobiotics: a novel class of psychotropic. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;74:720–726. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distrutti E., O'Reilly J.A., McDonald C., Cipriani S., Renga B., Lynch M.A., Fiorucci S. Modulation of intestinal microbiota by the probiotic VSL#3 resets brain gene expression and ameliorates the age-related deficit in LTP. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106503. e106503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnet-Hughes A., Perez P.F., Dore J., Leclerc M., Levenez F., Benyacoub J., Serrant P., Segura-Roggero I., Schiffrin E.J. Potential role of the intestinal microbiota of the mother in neonatal immune education. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010;69:407–415. doi: 10.1017/S0029665110001898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckburg P.B., Bik E.M., Bernstein C.N., Purdom E., Dethlefsen L., Sargent M., Gill S.R., Nelson K.E., Relman D.A. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005;308:1635–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Aidy S., Kunze W., Bienenstock J., Kleerebezem M. The microbiota and the gut-brain axis: insights from the temporal and spatial mucosal alterations during colonisation of the germfree mouse intestine. Benef. Microbes. 2012;3:251–259. doi: 10.3920/BM2012.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epel E., Lapidus R., McEwen B., Brownell K. Stress may add bite to appetite in women: a laboratory study of stress-induced cortisol and eating behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erny D., Hrabe de Angelis A.L., Jaitin D., Wieghofer P., Staszewski O., David E., Keren-Shaul H., Mahlakoiv T., Jakobshagen K., Buch T., Schwierzeck V., Utermohlen O., Chun E., Garrett W.S., McCoy K.D., Diefenbach A., Staeheli P., Stecher B., Amit I., Prinz M. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18:965–977. doi: 10.1038/nn.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith J.J., Rey F.E., O'Donnell D., Karlsson M., McNulty N.P., Kallstrom G., Goodman A.L., Gordon J.I. Creating and characterizing communities of human gut microbes in gnotobiotic mice. ISME J. 2010;4:1094–1098. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger B.C., Dinan T.G., Cryan J.F. High-fat diet selectively protects against the effects of chronic social stress in the mouse. Neuroscience. 2011;192:351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folks D.G. The interface of psychiatry and irritable bowel syndrome. Curr. Psychiatr. Rep. 2004;6:210–215. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe P., Kunze W.A., Bienenstock J. On communication between gut microbes and the brain. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2012;28:557–562. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283572ffa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe P., Bienenstock J., Kunze W.A. Vagal pathways for microbiome-brain-gut axis communication. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014;817:115–133. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J.A., McVey Neufeld K.A. Gut-brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraher M.H., O'Toole P.W., Quigley E.M. Techniques used to characterize the gut microbiota: a guide for the clinician, Nature reviews. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;9:312–322. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaci N., Borrel G., Tottey W., O'Toole P.W., Brugere J.F. Archaea and the human gut: new beginning of an old story. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16062–16078. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gacias M., Gaspari S., Santos P.M., Tamburini S., Andrade M., Zhang F., Shen N., Tolstikov V., Kiebish M.A., Dupree J.L., Zachariou V., Clemente J.C., Casaccia P. Microbiota-driven transcriptional changes in prefrontal cortex override genetic differences in social behavior. eLife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.13442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galley J.D., Nelson M.C., Yu Z., Dowd S.E., Walter J., Kumar P.S., Lyte M., Bailey M.T. Exposure to a social stressor disrupts the community structure of the colonic mucosa-associated microbiota. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareau M.G. Microbiota-gut-brain axis and cognitive function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014;817:357–371. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareau M.G., Silva M.A., Perdue M.H. Pathophysiological mechanisms of stress-induced intestinal damage. Curr. Mol. Med. 2008;8:274–281. doi: 10.2174/156652408784533760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genton L., Kudsk K.A. Interactions between the enteric nervous system and the immune system: role of neuropeptides and nutrition. Am. J. Surg. 2003;186:253–258. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon M.D., Tack J. The serotonin signaling system: from basic understanding to drug development for functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:397–414. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehler L.E. Vagal complexity: substrate for body-mind connections? Bratisl. Lek. listy. 2006;107:275–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golubeva A.V., Crampton S., Desbonnet L., Edge D., O'Sullivan O., Lomasney K.W., Zhdanov A.V., Crispie F., Moloney R.D., Borre Y.E., Cotter P.D., Hyland N.P., O'Halloran K.D., Dinan T.G., O'Keeffe G.W., Cryan J.F. Prenatal stress-induced alterations in major physiological systems correlate with gut microbiota composition in adulthood. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;60:58–74. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenham S., Clarke G., Cryan J.F., Dinan T.G. Brain-gut-microbe communication in health and disease. Front. Physiol. 2011;2:94. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover M., Kashyap P.C. Germ-free mice as a model to study effect of gut microbiota on host physiology. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014;26:745–748. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulhane M., Murray L., Lourie R., Tong H., Sheng Y.H., Wang R., Kang A., Schreiber V., Wong K.Y., Magor G., Denman S., Begun J., Florin T.H., Perkins A., Cuiv P.O., McGuckin M.A., Hasnain S.Z. High fat diets induce colonic epithelial cell stress and inflammation that is reversed by IL-22. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:28990. doi: 10.1038/srep28990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkin A., Kelly J.P., McNamara M., Connor T.J., Dredge K., Redmond A., Leonard B.E. Activity and onset of action of reboxetine and effect of combination with sertraline in an animal model of depression. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;364:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt M.A., Hoffmann C., Sherrill-Mix S.A., Keilbaugh S.A., Hamady M., Chen Y.Y., Knight R., Ahima R.S., Bushman F., Wu G.D. High-fat diet determines the composition of the murine gut microbiome independently of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:e1711–1712. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.042. 1716-1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]