INTRODUCTION

Speech and language delay in children is a common presentation to primary care either directly to the GP or through the health visitor, affecting approximately 6% of pre-school children.1 Young children, particularly those with speech delay, can be difficult to examine. Differentiation between an isolated pathology and those with concurrent global developmental delay is crucial. This article presents an example of a common case, considers the learning points, and highlights management principles.

CASE HISTORY

A 2-year-old boy presented to primary care with fewer words than his peers, and with difficulty in non-family members understanding him. On closer questioning he had <10 words of speech. He was born at 39 weeks by normal delivery, not requiring special care baby unit, and passed his newborn hearing screening. Review of his Personal Child Health Record (red book) showed consistent growth along centile lines, and other developmental milestones attained. In the consultation room he played appropriately, made good eye contact, and followed instructions: identifying his nose and ears when asked. On examination, he had normal facies, and otoscopy revealed bilateral dull tympanic membranes.

Referral to audiology was made and age- appropriate free-field hearing testing with tympanometry performed. He had hearing thresholds of >40 dB (mild-to-moderate hearing loss) with flat tympanograms indicating a conductive loss in keeping with otitis media with effusion (OME).

For 3 months the child was actively observed and then referred to the ear, nose, and throat consultant. With evidence of persistent conductive hearing loss, he was offered hearing aids or grommets, in keeping with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines.2 His parents elected for grommet insertion. On follow-up at 2 years, 6 months, his vocabulary had expanded to >100 words, and audiogram showed thresholds <20 dB in the normal range.

ASSESSMENT AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Speech and language delay must be separated from variation in speech development, and is defined by children falling behind recognised milestones. Regression or loss of speech and language are particularly concerning.

Initially, a history with a focus on identifying a cause for the speech delay should be taken, including pregnancy and birth history, developmental milestones, and family history.

Aspects of the antenatal history that may impact on newborn hearing must be explored. These include TORCH interuterine infections (toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex) and maternal drug exposure. Important aspects of the perinatal history include prematurity, hypoxia, birth trauma, and neonatal jaundice. Newborn hearing screening does not occur worldwide and should not be assumed in births outwith the UK. General maternal health is useful, particularly for the exclusion of conditions such as hypothyroidism.

The child’s medical history should be covered, including conditions such as meningitis, head trauma, and seizures, and exposure to ototoxic drugs. Developmental milestones should be noted, including social interactions with peers and family. This is not only to explore the possibility of a global developmental delay/disorder and the possibility of an underlying psychological diagnosis, but may also highlight deprivation and neglect.

It is important to enquire about any family history of hearing loss and speech delay including the possibility of consanguinuity, which may point to metabolic or recessive conditions.

In multilingual children total words across all languages should be counted, and will often compensate for the perceived delay.5

Examination should be global, observing behaviour but with a focus on otoscopy, which may provide instant diagnosis of common conditions such as OME. Observed or formal neurological assessment of fine and gross motor skills may highlight a global development delay, with head circumference a useful adjunct.

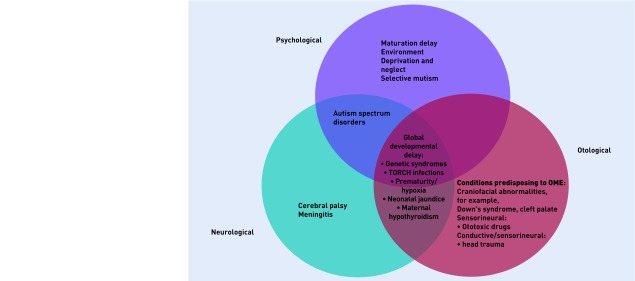

There are multiple causes of speech delay, which can be split into psychological, neurological, and otological (Figure 1). There is a known association between confirmed speech and language delay and psychiatric disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, with up to 50% occurring concurrently.6

Figure 1.

Venn diagram demonstrating the different causes of speech and language delay (adapted from the Oxford Handbook of Paediatrics4). OME = otitis media with effusion. TORCH = toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex.

In syndromic children, especially those with craniofacial abnormalities the speech delay may be multifactorial and a multidisciplinary approach with multiple referrals required.

One of the challenges in assessing a child with speech and language delay is that the order of learning and speech and language acquisition is fixed, but there is significant variation in timings described.7 Up to 60% of children with speech delay do not require intervention and the problem resolves spontaneously by 3 years of age.1 It is therefore important to undertake an individualised approach to each child.

MANAGEMENT

Diagnosis of the underlying causation of speech delay is the priority and guides management. All children with suspected speech delay should be referred for audiometry to exclude hearing loss as this is a potentially reversible cause in the setting of OME with appropriate intervention.

Other causes that should not be missed include global developmental delay and psychiatric disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, both of which will require a multidisciplinary approach with enhanced potential outcomes for the child if support and treatment are offered earlier. Ultimately these children will require input from a child development centre.

Children with craniofacial abnormalities, for example, Down’s syndrome, may suffer from both conductive deafness and development delay, which will be confounded if not treated.

In the case described the child was suffering from speech delay secondary to OME. This is the commonest cause of hearing impairment in the developed world8 and is reversible. OME has two peaks of incidence at 2 and 5 years.9 The current treatment strategy for OME is grommet insertion after a recommended 3-month period of watchful waiting2 to allow for spontaneous effusion resolution. Hearing aids are a non-surgical alternative but are generally seen as socially unacceptable. Twenty-five per cent of children will require further grommet insertion within 2 years of the first,10 with a mean number of grommet insertions per child of 2.1.11 This emphasises the recurrent nature of OME and the importance of close follow-up for these children.

Speech and language delay may be an early presenting feature in children with global developmental delay, and provides a crucial early opportunity to intervene and provide multidisciplinary support. Prompt audiological assessment is essential in all children with speech and language delay to exclude reversible causes.

Patient consent

The case presented here is fictional and therefore consent was not required.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Law J, Boyle J, Harris F, et al. Screening for speech and language delay: a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2(9):1–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Otitis media with effusion in under 12s: surgery CG60. 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg60 (accessed 13 Oct 2017) [PubMed]

- 3.Leung AK, Kao CP. Evaluation and management of the child with speech delay. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(11):3121–3128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasker R, McClure R, Acerini C, editors. Oxford handbook of paediatrics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellman M, Byrne O, Sege R. Developmental assessment of children. BMJ. 2013;346:e8687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beitchman JH. Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with language and learning disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(10):1117–1119. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199810000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, et al. Variability in early communicative development. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994;59(5):1–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandel EM, Doyle WJ, Winther B, Alper CM. The incidence, prevalence and burden of OM in unselected children aged 1–8 years followed by weekly otoscopy through the ‘common cold’ season. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(4):491–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zielhuis GA, Straatman H, Rach GH, van den Broek P. Analysis and presentation of data on the natural course of otitis media with effusion in children. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19(4):1037–1044. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.4.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gates GA, Avery CA, Prihoda T, Cooper JC., Jr Effectiveness of adenoidectomy and tympanostomy tubes in the treatment of chronic otitis media with effusion. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(23):1444–1451. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712033172305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniel M, Vaghela H, Philpott C, et al. Does the benefit of adenoidectomy in addition to ventilation tube insertion persist long term? Clin Otol. 2006;31(6):580. [Google Scholar]