Abstract

Background

The NHS Health Check programme is a prevention initiative offering cardiovascular risk assessment and management advice to adults aged 40–74 years across England. Its effectiveness depends on uptake. When it was introduced in 2009, it was anticipated that all those eligible would be invited over a 5-year cycle and 75% of those invited would attend. So far in the current cycle from 2013 to 2018, 33.8% of those eligible have attended, which is equal to 48.5% of those invited to attend. Understanding the reasons why some people do not attend is important to maximise the impact of the programmes.

Aim

To review why people do not attend NHS Health Checks.

Design and setting

A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies.

Method

An electronic literature search was carried out of MEDLINE, Embase, Health Management Information Consortium, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Global Health, PsycINFO, Web of Science, OpenGrey, the Cochrane Library, NHS Evidence, Google Scholar, Google, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the ISRCTN registry from 1 January 1996 to 9 November 2016, and the reference lists of all included papers were also screened manually. Inclusion criteria were primary research studies that reported the views of people who were eligible for but had not attended an NHS Health Check.

Results

Nine studies met the inclusion criteria. Reasons for not attending included lack of awareness or knowledge, misunderstanding the purpose of the NHS Health Check, aversion to preventive medicine, time constraints, difficulties with access to general practices, and doubts regarding pharmacies as appropriate settings.

Conclusion

The findings particularly highlight the need for improved communication and publicity around the purpose of the NHS Health Check programme and the personal health benefits of risk factor detection.

Keywords: NHS Health Check, patient non-attendance, qualitative research, systematic review, uptake

INTRODUCTION

The NHS Health Check programme was introduced in England in 2009. The programme aims to offer individuals aged 40–74 years without pre-existing cardiovascular disease (CVD), kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, or dementia an assessment of their risk of developing such conditions and access to lifestyle and health advice to reduce that risk. The risk assessment includes questions about alcohol use, physical activity, and smoking status, measurement of weight, height, and blood pressure, and blood tests for cholesterol and diabetes if they have a body mass index >30 (or >27 if they are South Asian) or a blood pressure >140/90 mmHg, and for creatinine to assess kidney function in those with a blood pressure >140/90 mmHg. Individuals are then given their estimated risk of developing CVD in the next 10 years and provided with lifestyle advice for prevention of CVD and dementia. Where appropriate, referrals to specialist lifestyle services or follow-up with their GP to discuss medication are also advised. It is now a mandated service, with NHS Health Checks offered in a variety of settings, including general practices, pharmacies, and community settings.

When the programme was introduced, it was anticipated that all those eligible would be invited over a 5-year cycle and 75% would attend.1 The most recent published data from Public Health England show that, so far in the current cycle from 2013 to 2018, 10 735 566 (69.7%) of the total eligible population of 15 402 612 people have been invited and 5 209 468 (33.8%) have attended,2 giving an overall proportion of those invited who have taken up the invitation of 48.5%. This varies both between and within regions of the country, for example, within Yorkshire in 2015–2016, uptake of NHS Health Checks varied from 8% to 89% between areas.

As the potential benefits of the programme depend on people receiving NHS Health Checks, understanding this variation and why some people do not attend is important. Quantitative studies have shown that older people, females, those from the most deprived areas, and non-smokers are more likely to have had an NHS Health Check, while older people and those from the least deprived areas are more likely to take up an invitation if offered.3–8

The aim of this study was to systematically review and synthesise the published qualitative literature exploring why people have not attended NHS Health Checks in order to better understand these variations in uptake at an individual level.

How this fits in

Attendance at NHS Health Checks has been lower than anticipated when the programme was introduced. Understanding the reasons why some people do not attend is important to maximise the impact of the programme. A number of studies have been published in this area. This review synthesises the findings from those studies and highlights a need for clearer and more targeted communication, clarification of the distinction between prevention and treatment and appointments for NHS Health Checks, and those for routine and urgent care, and promotion of pharmacies and community venues as appropriate settings.

METHOD

Search strategy

Existing searches were used that had previously been conducted by Public Health England in MEDLINE, Embase, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Global Health, PsycINFO, the Cochrane Library, NHS Evidence, Google Scholar, Google, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the ISRCTN registry from 1 January 1996 to 9 November 2016. These were supplemented with searches in Web of Science and OpenGrey for the same period. The OAIster database was unavailable at the time of the search. The full search strategy for each of the databases is available from the authors on request. All searches included terms relating to ‘health check’, ‘NHS Health Check’, and ‘cardiovascular disease’.

Study selection

Identified studies were selected for inclusion in a two-stage process. First, an information scientist at Public Health England conducted initial searches and identified all studies relevant to the NHS Health Check. Second, this process was repeated for the searches in Web of Science and OpenGrey. All articles identified as relevant to NHS Health Checks were then reviewed at full-text level against the specific inclusion criteria for this study. Studies were included that considered participants eligible for an NHS Health Check but who had not attended, and that included qualitative data. Editorials, commentaries and opinion pieces, studies including individuals who were not eligible for an NHS Health Check, and studies that focused on screening or health check services other than the NHS Health Check were all excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The data from these studies were extracted independently by at least two researchers, each from a different disciplinary background (academic general practice, public services, and health systems and innovation), using standardised extraction forms. Quality assessment was performed at the same time as data extraction across eight dimensions based on the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP).9 Studies were not excluded on the basis of quality alone.

Synthesis

A thematic synthesis of the data was conducted in three stages as described in detail elsewhere.10 Briefly, first line-by-line verbatim coding of key findings was performed from the included sample of studies. Following this initial extraction, a workshop was arranged during which the similarities and discrepancies in the coding from the three researchers were discussed and the findings were organised into related areas to develop descriptive themes. A series of consensus meetings were then held, during which similarities and discrepancies across the studies and themes were discussed, and overarching analytical themes were developed that addressed the research question. The purpose of this final stage was to enable the ‘translation of concepts from one study to another’.11 Illustrative quotations from the original studies are included alongside the analytical themes in this article to enable an appreciation of the primary data.

RESULTS

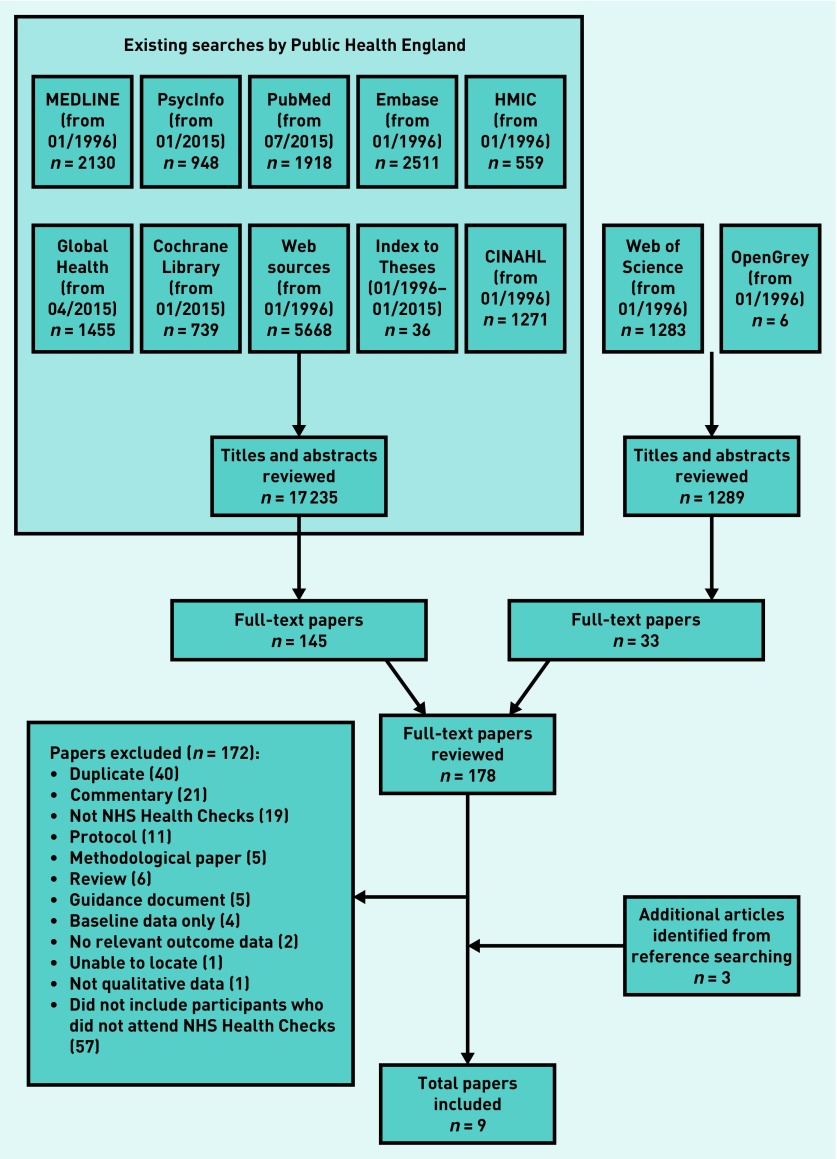

From the initial 18 524 articles identified and screened from the searches, 178 were reviewed at full-text level. After excluding duplicates, commentaries, and studies not meeting the inclusion criteria, and including studies from reference searches, nine studies were identified that are relevant to the study question (Figure 1). Table 1 provides details of the characteristics of these nine studies, including the methods for data collection, location, and setting. The studies used a range of methods, including face-to-face or telephone interviews (n = 5), face-to-face surveys (n = 2), and surveys with space for free text (n = 2). Across the studies, general practices were the predominant intended setting for NHS Health Checks (n = 7), while some studies focused on reasons for not attending NHS Health Checks at pharmacies (n = 2), community settings (n = 1), or any setting (n = 1). Together the studies covered a number of regions across England, including London, the North East, North West, West Midlands, and South West regions. Based on the CASP criteria (Table 2), three studies were of high quality overall, four were of medium quality, and two were low quality. Thematic synthesis of these nine studies identified six key themes for why people had not attended NHS Health Checks: lack of awareness or knowledge; misunderstanding the purpose; aversion to preventive medicine; time constraints or competing priorities; difficulty with access in general practices; and concern around the pharmacy as a setting. The primary articles contributing to each of those themes are shown in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies including the views of people who had not taken up an offer of an NHS Health Check

| Author (year) | Type of report | Region | Setting of NHS Health Checks | Data collection method | Participants, n | Recruitment of non-attenders | Participant characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burgess et al (2015)15 | Journal article | South London | Four general practices | Semi-structured interviews | 10 | Purposive sampling by age, sex, and attendance of patients who had been invited but not attended | 7 females, 3 males Predominantly white ethnicity |

| Ellis et al (2015)14 | Journal article | Stoke-on-Trent | Four general practices | Telephone and face-to-face semi-structured interviews | 41 | 500 letters of invitation sent by GPs to those who had not taken up the invitation for an NHS Health Check. Incentivised with the offer of £15 to participate | 22 females, 19 males Mean age 52.9 ± 8.5 Sociodemographically representative of non-attendees |

| NHS Greenwich (2011)17 | Evaluation report | Greenwich | Clinic and community setting | In-depth telephone interviews | 10 | Recruited through social marketing by social marketing professionals | Not given |

| Health Diagnostics (2014)16 | Case studies | North East of England | General practice, pharmacy | Face-to-face survey | 325 | Recruited on the street | Not given |

| Jenkinson et al (2015)19 | Journal article | Torbay | Four general practices | Face-to-face and telephone interviews | 10 | Letters of invitation to a random sample stratified by age and sex of those who had not responded to an invitation | 6 females, 4 males 4 employed, 1 unemployed,5 retired |

| Krska et al (2015)20 | Journal article | Sefton, an area in North West England | 16 general practices | Postal survey with free-text responses | 210 | Postal survey to all patients with estimated 10-year CVD risk >20% | 46 females, 164 males 67%>65 years, 99.5% white 14.6% highest quintile of deprivation 9.2% lowest quintile of deprivation |

| McDermott et al (2016)18 | HTA report | Lambeth and Lewisham | 18 general practices | Content analysis of questionnaire | Not given | Questionnaires sent to all participants in the two intervention arms of a trial of enhanced invitation methods | Not given |

| Oswald et al (2010)13 | Evaluation report | Teesside | Any | Semi-structured interviews | 51 | Participants approached on the street at job centres, working men’s clubs, and libraries | Not given |

| Taylor et al (2012)12 | Journal article | Sefton PCT | Pharmacy | Face-to-face survey | 261 | High-street locations, community centres, and other social settings in the vicinity | 172 females, 89 males 20.7% 35–45 years 30.6% 46–55 years 23.4% 56–65 years 25.3% 66–75 years |

CVD = cardiovascular disease. HTA = Health Technology Assessment. PCT = primary care trust.

Table 2.

Results from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme quality assessment checklist

| Author (year) | Study addressed a clearly focused issue | Appropriateness of qualitative method | Design | Recruitment | Consideration of relationship between research and participants | Ethical issues | Rigour of data analysis | Clarity of statement of findings | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burgess et al (2015)15 | ● | ● | ● | • | ∙ | • | ● | ● | High |

| Ellis et al (2015)14 | ● | ● | ● | ● | • | • | ● | ● | High |

| Health Diagnostics (2014)16 | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | Low |

| NHS Greenwich (2011)17 | ● | ● | ● | • | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | • | Medium |

| Jenkinson et al (2015)19 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ∙ | ● | ● | ● | High |

| Krska et al (2015)20 | ● | ● | • | ● | n/a | • | • | • | Medium |

| McDermott et al (2016)18 | • | ∙ | • | ∙ | ∙ | • | ∙ | • | Low |

| Oswald et al (2010)13 | ● | ● | ● | • | ∙ | • | • | • | Medium |

| Taylor et al (2012)12 | ● | • | ● | ● | ∙ | • | ∙ | • | Medium |

∙= Low. • = Medium. ● = High.

Table 3.

Key themes associated with each study

| Author (year) | Lack of awareness or knowledge | Time constraints or competing priorities | Lack of clarity around purpose | Aversion to preventive medicine | Difficulty with access in general practices | Concern around the pharmacy as a setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burgess et al (2015)15 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Ellis et al (2015)14 | x | x | x | x | x | |

| NHS Greenwich (2011)17 | x | x | x | x | ||

| Health Diagnostics (2014)16 | x | x | ||||

| Jenkinson et al (2015)19 | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Krska et al (2015)20 | x | x | ||||

| McDermott et al (2016)18 | x | x | ||||

| Oswald et al (2010)13 | x | x | x | x | ||

| Taylor et al (2012)12 | x | x |

X = yes.

Except for the final theme, concern around the pharmacy as a setting, which was not applicable to those studies based in general practice, each theme was present in over half the studies and all three high-quality studies included data relevant to all the themes. The three survey studies each only contributed to two of the themes but there were no other clear patterns across the findings and recruitment method, patient group, site of the NHS Health Checks, or region. Details of each of the themes are given next. Though the findings are presented by theme, there is overlap between them and it is likely that each individual was influenced by at least one reason.

Lack of awareness or knowledge

A low level of awareness of NHS Health Checks was evident across a number of the studies.12–15 Some participants had either no knowledge of the NHS Health Check or no recollection of receiving an invitation,14,16 and 91% of those taking part in a face-to-face survey on the street reported being unaware of an NHS Health Check pharmacy service.12 Others appeared to be aware of the programme but a lack of knowledge about what it involved had contributed to their non-attendance:17–19

‘Are they free? How do you go about getting a Health Check?’18

‘I didn’t realise that it was dementia … And I certainly didn’t know that it was, um, diabetes and kidney, I thought it was purely cholesterol.’19

Misunderstanding the purpose

In addition to this lack of awareness or knowledge, there was a lack of clarity around the purpose or objective of the NHS Health Checks. This lack of understanding led some individuals to feel apprehensive about the results and the potential for health issues to be uncovered, particularly among some females.14,19 Others had not recognised the preventive role of the programme and so felt that if they were in good health or visited their GP regularly that a check-up was unnecessary,13–15 and did not wish to divert time or resources from others or place a burden on their doctor or the NHS:14–16,19

‘I mean there’s no point in doing that if it’s, you know, using up people’s precious time and resources if it’s not necessary.’15

‘It’s beneficial for those already having problems, but for me I’m fit and active, you should go when you’re poorly, not just for the sake of it.’14

Aversion to preventive medicine

Others appeared to be aware of the NHS Health Check programme and understood its preventive purpose but were unwilling to attend.13–15,19,20 For some this was because they were just not interested,17 whereas others ‘did not want to know’,13,15 or were afraid of receiving negative news about their health.14,15,19 Others appeared to avoid attending because they did not wish to be ‘told off’ or given lifestyle advice,13,15,19 and some reported that negative views from friends influenced their decision to attend or not:19

‘I am just the type of person who wouldn’t want to know. I would rather things just happen and then deal with it. I worry about the now and not the future.’13

‘You go for a check and something is discovered … I hear lots of people end up going for so many tests, and worry about their health.’14

Time constraints or competing priorities

Other frequently cited reasons for non-attendance included time constraints or conflicting priorities.14,16,17,19,21 Some stated being ‘too busy’ as a reason for non-attendance and some found it difficult to arrange an appointment that suited their daily schedules, which included work, caring for others, and travelling abroad:14,15,17

‘… And, you know, when you work freelance, any spare time you have to work, you know to keep the financial thing on track. So you know, it’s just life, you just kind of do what’s in front of you.’15

Difficulty with access in general practices

The two final themes relate to setting specific barriers to attendance. In general practice settings, an actual or perceived difficulty in obtaining an appointment was the most common barrier, particularly for those who worked normal office hours, and those with carer responsibilities:13–15,18,19

‘It is just the time to arrange to go in … I … come to work early and they are shut. They are shut when I go home. Weekends they are not open, so it’s difficult to get there.’14

‘It’s very difficult for me to [go to the appointment] and hold on to a nine-to-five job. It means I have to take personal time off from my employer to do this. They don’t give you an option where you can go in the evening.’15

Concern around the pharmacy as a setting

Among those invited to attend NHS Health Checks in pharmacies, the reasons for not attending related less to access but more to concerns regarding privacy, confidentiality, and pharmacists’ competence, with males demonstrating less willingness to be screened at a pharmacy than females:2,15

‘Not enough privacy in small pharmacy — unless special rooms are kept just for that. Don’t feel they are qualified.’12

‘The relationship with pharmacies is a consumer one, about products, and not about care and health … potentially it’s pretty intimate information. It should not be the place for delivering bad news about cholesterol.’15

DISCUSSION

Summary

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic synthesis of qualitative evidence about why people do not attend NHS Health Checks. It highlights three particular groups of individuals: those who were unaware of the NHS Health Checks programme; those who were aware of the programme but did not appreciate the preventive nature; and those who recognised the preventive nature but actively chose not to engage either because they did not want to be ‘told off’, or because of a preference for simply ‘not wanting to know’. There is also evidence of practical barriers to attendance, such as time constraints or competing priorities among those with work and carer obligations. In addition, for GP and pharmacy settings, perceived or actual difficulties making an appointment, wishing to avoid the GP, or concerns about pharmacy and the pharmacist’s role in conducting NHS Health Checks also contributed to decisions not to attend.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this study are the systematic literature search, including the OpenGrey database and web-based searches to locate unpublished studies, and the independent data extraction by three researchers, each with different academic backgrounds. Given the highly interpretive nature of qualitative data, the decision to include three researchers in this step of the research and to hold a series of subsequent consensus meetings with the wider research team reduced the risk of introducing bias to the results. The choice of thematic synthesis also enabled the development of additional interpretations and conceptual insights beyond the findings of the primary studies. For example, the aversion to preventive medicine theme described here was not explicitly described within the studies.

However, although three researchers conducted the data extraction, only one qualitative researcher conducted the title and abstract review for the Web of Science and OpenGrey literature search results and this study relied on the screening that had already been performed by Public Health England in the other databases. It is, therefore, possible that additional studies relevant to the research question might have been overlooked.

Other limitations are the relatively small number of studies that focus on reasons for non-attendance at an NHS Health Check and the varying levels of quality of these studies. The studies all included only small numbers of participants who were self-selecting because they had agreed to take part in the research. As acknowledged in a number of the studies, non-attenders are a particularly difficult group to recruit because they have already not engaged with the NHS Health Check programme. Whether the participants’ views are representative of the large group who do not attend is, therefore, not known. It is also not possible to assess the relative contribution of each of the themes described. In qualitative analysis it is common for divergent themes to be specifically sought and for data collection to continue until no new themes arise. It is, therefore, possible that some of the reasons reported in this study are only applicable to a small number of those not attending NHS Health Checks. The analysis in this systemic review also relied on the data presented in the included studies, which meant it was not possible to identify whether some findings were more common among specific patient groups.

Comparison with existing literature

Few studies have explored reasons for non-attendance in prevention programmes. The findings of the current study are consistent with data from interviews with 259 people who had not attended similar health checks before the introduction of the NHS Health Check programme.21 In that study, 9% did not recall receiving an invitation and the main reasons given for not attending were practical reasons, including lack of time and difficulties scheduling an appointment; a belief that screening was not necessary for them, either because they felt well or were already in contact with medical services; and lack of interest.

The reasons given are also comparable with existing literature exploring the reasons people do not attend screening or immunisation programmes. For example, studies have shown that people who declined bowel cancer screening felt that undergoing screening left them vulnerable to receiving unwanted news about poor health,22 they did not want to waste resources, and they had other competing priorities.23 The concern about not wanting to waste resources has also been reported in studies exploring why people in the UK do not seek help with symptoms of cancer,24,25 or childhood illness,26 and similar concerns around public trust in pharmacies as settings for health care as found in this study have also been reported elsewhere.27

Despite the similarity in findings across the studies, establishing the relative importance of these factors is, however, difficult. To the authors’ knowledge, only one study has reported quantitative data on reasons for non-attendance and non-uptake to NHS Health Checks.6 In that study reasons for not attending or not taking up an invitation that had been entered during routine care were extracted from the medical records of patients in 37 general practices. Reasons were only available for less than 20% of patients, with comorbidities or already being reviewed in general practice being the most commonly reported.

Implications for research and practice

This study highlights a number of findings of relevance to policymakers and healthcare professionals delivering NHS Health Checks, as well as those involved in planning and delivering other prevention programmes, such as the recently introduced NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme (https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/qual-clin-lead/diabetes-prevention/). In particular, it suggests three areas for action at a policy or practical level.

The first is a need for clearer and more targeted communication about the NHS Health Check programme as a whole and its purpose. Lessons learned from screening programmes and the drive towards increasing shared decision making highlight the need to provide appropriately balanced evidence concerning benefits and harms to enable informed decision making. This study shows that, despite the programme having been in place for 8 years, some people remain unaware of it, and many of those who were aware had misunderstood the purpose or did not appreciate the potential benefits of prevention and early detection. Modifying invitation letters,8,28 incorporating text message reminders,28 or offering pre-booked appointments29 may also potentially help those wishing to attend.

Second, offering evening or early morning appointments in general practice settings and clarifying the distinction between appointments for NHS Health Checks and appointments for routine and urgent care may provide opportunities for more people to attend, and reduce patient concerns that by attending they are taking up resources.

Finally, delivering NHS Health Checks in pharmacy and community settings could be promoted and awareness raised among the general public of the suitability of pharmacies as sites for NHS Health Checks, and the training pharmacists receive. In addition to reducing concern that by attending an NHS Health Check individuals are placing an unnecessary burden on general practice resources when they feel they are in good health, this might also encourage uptake of other services provided by pharmacies.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to patient and public representatives Kathryn Lawrence and Chris Robertson for providing helpful comments on the findings and the NHS Health Checks Expert Scientific and Clinical Advisory Panel working group for providing the initial literature search conducted by Public Health England. The authors would also like to thank Anna Knack, Research Assistant at RAND Europe, for her excellent research support, and Emma Pitchforth for her helpful comments on our analysis

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from Public Health England. Juliet A Usher-Smith was funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Lectureship and Fiona M Walter by an NIHR Clinician Scientist award (RG 68235). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. All researchers were independent of the funding body and the funder had no role in data collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health . Economic modelling for vascular checks. London: DH; 2008. www.healthcheck.nhs.uk/document.php?o=225 (accessed 13 Nov 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS Explore NHS health check data. http://www.healthcheck.nhs.uk/commissioners_and_providers/data/ (accessed 14 Nov 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang KC, Soljak M, Lee JT, et al. Coverage of a national cardiovascular risk assessment and management programme (NHS Health Check): retrospective database study. Prev Med. 2015;78:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robson J, Dostal I, Sheikh A, et al. The NHS Health Check in England: an evaluation of the first 4 years. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e008840. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artac M, Dalton AR, Babu H, et al. Primary care and population factors associated with NHS Health Check coverage: a national cross-sectional study. J Public Health (Oxf) 2013;35(3):431–439. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdt069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cochrane T, Gidlow CJ, Kumar J, et al. Cross-sectional review of the response and treatment uptake from the NHS Health Checks programme in Stoke on Trent. J Public Health (Oxf) 2013;35(1):92–98. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fds088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalton AR, Bottle A, Okoro C, et al. Uptake of the NHS Health Checks programme in a deprived, culturally diverse setting: cross-sectional study. J Public Health (Oxf) 2011;33(3):422–429. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sallis A, Bunten A, Bonus A, et al. The effectiveness of an enhanced invitation letter on uptake of National Health Service Health Checks in primary care: a pragmatic quasi-randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:35. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0426-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CASP UK Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists. http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists (accessed 13 Nov 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor J, Krska J, Mackridge A. A community pharmacy-based cardiovascular screening service: views of service users and the public. Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20(5):277–284. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2012.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oswald N, McNaughton R, Watson P, Shucksmith J. Tees Vascular Assessment Programme: evaluation commissioned by the Tees Primary Care Trusts (PCT) from the Centre for Translational Research in Public Health. Middlesbrough: Teesside University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellis N, Gidlow C, Cowap L, et al. A qualitative investigation of non-response in NHS health checks. Arch Public Health. 2015;73(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0064-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burgess C, Wright AJ, Forster AS, et al. Influences on individuals’ decisions to take up the offer of a health check: a qualitative study. Heal Expect. 2015;18(6):2437–2448. doi: 10.1111/hex.12212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health Diagnostics A picture of health NHS Health Checks case study: the North East of England. 2014 https://www.healthdiagnostics.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/NE_Case_Study-4.pdf (accessed 13 Nov 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenwich NHS. Evaluation of NHS Health Check plus community outreach programme in Greenwich. London: NHS Greenwich; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDermott L, Wright AJ, Cornelius V, et al. Enhanced invitation methods and uptake of health checks in primary care: randomised controlled trial and cohort study using electronic health records. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(84):1–92. doi: 10.3310/hta20840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkinson CE, Asprey A, Clark CE, Richards SH. Patients’ willingness to attend the NHS cardiovascular health checks in primary care: a qualitative interview study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:33. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0244-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krska J, du Plessis R, Chellaswamy H. Views and experiences of the NHS Health Check provided by general medical practices: cross-sectional survey in high-risk patients. J Public Health. 2015;37(2):210–217. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pill R, Stott N. Invitation to attend a health check in a general practice setting: the views of a cohort of non-attenders. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1988;38(307):57–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer CK, Thomas MC, von Wagner C, Raine R. Reasons for non-uptake and subsequent participation in the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme: a qualitative study. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(7):1705–1711. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall N, Birt L, Rees CJ, et al. Concerns, perceived need and competing priorities: a qualitative exploration of decision-making and non-participation in a population-based flexible sigmoidoscopy screening programme to prevent colorectal cancer. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e012304. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forbes LJ, Atkins L, Thurnham A, et al. Breast cancer awareness and barriers to symptomatic presentation among women from different ethnic groups in East London. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(10):1474–1479. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cromme SK, Whitaker KL, Winstanley K, et al. Worrying about wasting GP time as a barrier to help-seeking: a community-based, qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X685621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Francis NA, Crocker JC, Gamper A, et al. Missed opportunities for earlier treatment? A qualitative interview study with parents of children admitted to hospital with serious respiratory tract infections. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(2):154–159. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.188680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gidman W, Ward P, McGregor L. Understanding public trust in services provided by community pharmacists relative to those provided by general practitioners: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(3):e000939. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alpsten T. Saving lives through effective patient engagement around NHS health checks. Clinical Governance. 2015;20(3):108–112. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Local Government Association . Checking the health of the nation: implementing the NHS Health Check Programme. Case studies. London: LGA; 2015. [Google Scholar]