Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: critical care, cognition, personnel staffing, risk, safety

Abstract

Objectives:

The aims of this study were to 1) examine individual professionals’ perceptions of staffing risks and safe staffing in intensive care and 2) identify and examine the cognitive processes that underlie these perceptions.

Design:

Qualitative case study methodology with nurses, doctors, and physiotherapists.

Setting:

Three mixed medical and surgical adult ICUs, each on a separate hospital site within a 1,200-bed academic, tertiary London hospital group.

Subjects:

Forty-four ICU team members of diverse professional backgrounds and seniority.

Interventions:

None.

Main Results:

Four themes (individual, team, unit, and organizational) were identified. Individual care provision was influenced by the pragmatist versus perfectionist stance of individuals and team dynamics by the concept of an “A” team and interdisciplinary tensions. Perceptions of safety hinged around the importance of achieving a “dynamic balance” influenced by the burden of prevailing circumstances and the clinical status of patients. Organizationally, professionals’ risk perceptions affected their willingness to take personal responsibility for interactions beyond the unit.

Conclusions:

This study drew on cognitive research, specifically theories of cognitive dissonance, psychological safety, and situational awareness to explain how professionals’ cognitive processes impacted on ICU behaviors. Our results may have implications for relationships, management, and leadership in ICU. First, patient care delivery may be affected by professionals’ perfectionist or pragmatic approach. Perfectionists’ team role may be compromised and they may experience cognitive dissonance and subsequent isolation/stress. Second, psychological safety in a team may be improved within the confines of a perceived “A” team but diminished by interdisciplinary tensions. Third, counter intuitively, higher “situational” awareness for some individuals increased their stress and anxiety. Finally, our results suggest that professionals have varying concepts of where their personal responsibility to minimize risk begins and ends, which we have termed “risk horizons” and that these horizons may affect their behavior both within and beyond the unit.

Concerns over patient safety and subsequent risk management attempts have prompted an increasingly regulatory focus on ICU staffing (1, 2). The implementation and monitoring of critical care staffing standards, such as staff-to-patient ratios and the availability of staff for coordinating and “floating” roles, have become integral to day-to-day ICU management. Staffing standards are perceived to have regulatory implications, although arguably such standards may have a limited evidence-base, reduced adherence in practice, and potentially unintended consequences (3–6). For example, evidence exists that staff-to-patient ratios can be a blunt instrument, lacking responsiveness to rapidly changing patient numbers and needs (7) or the quality of work environment (8).

In many settings, ICUs are commonly required to manage a case-load which is somewhat beyond available capacity and work within an environment of financial constraints, high staff turnover, and staff shortages, which have the capacity to stress the “unit” and the individuals who work within it (9). In addition, the management of such situations can cause conflict and communication difficulties and solutions may evolve which involve compromise and erosions of normal “safe” practice; individuals respond to such challenges in a variety of different ways (10).

Few studies have assessed individual professionals’ perceptions of ICU staffing in a “bottom-up” way. There have been recent calls for more qualitative studies to understand human factors in the ICU from a clinical team perspective, and to explore the cognitive and behavioral issues that enable a clinical team to deliver optimal care (11). Although the call for behavioral research has been answered to some degree, we respond to the call to understand the cognitive processes that influence behavior and may affect the delivery of care (12). We define cognitive processes, in this context, as “the impact of perceptions of staffing on the individual professional’s internal cognitive processing in relation to risk.” We explore how this cognitive processing influences the behaviors of the team and in turn the operation of the unit and organization.

We draw on and develop specific social science theories to explore and perhaps explain how and why variations in professional and team behaviors occur. A cognitive approach provides a deeper understanding of the unseen issues that influence day-to-day practice and facilitates the exploration of practical solutions to overcome them. The aims of this study were to 1) examine individual professionals’ perceptions of staffing risks and safe staffing in intensive care and (2) identify and examine the cognitive processes that underlie these perceptions.

METHODS

Setting

The study was conducted across three adult ICUs within one hospital group consisting of three University Hospitals between November 2014 and November 2015.

Design

This study was a qualitative study based on individual interviews.

Ethics

Under U.K. research governance rules, studies involving staff members such as this do not require ethical committee review but do require institutional research governance approval. The study was reviewed and approved by Imperial College Healthcare Trust’s and Imperial College’s Joint Research Compliance Office, Reference number 13HH1823. All subjects provided written informed consent.

Participants

Semistructured interviews were conducted using a purposive sample with three core professional groups: nurses, doctors, and physiotherapists (Supplementary Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/C919).

Data Collection

Data collection was conducted largely by an Organizational Behaviorist (E.J.M.). The interview protocol contained two elements: first, a fictitious ICU staffing scenario that required participants to allocate below currently advised minimum staffing ratios to a fictitious unit of patients and secondly, general questions to initiate discussions on risk and safety in relation to staffing (Appendix A, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/CCM/C920). The staffing scenario was developed with the input of senior nursing and allied health professional staff and subsequently piloted. The goal was to explore individual perceptions and cognitive processes as participants “walked through” a hypothetical scenario that described an ICU under a certain amount of organizational challenge. The level of challenge was that which would be commonly encountered in a typical U.K. University Hospital; it was not designed to be overwhelming or a situation requiring “surge” management. The specific clinical scenario was designed to prompt reflection on where the boundary of safety and risk lay for that individual study participant. Previous experience during the piloting phase was that using a specific scenario at the beginning of such an interview prompted more in-depth reflection on the more general issues relating to risk and safety in relation to staffing (pilot phase data are not presented or discussed). Interviews were continued until saturation of thematic content was reached as conventionally determined (13). Interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

We analyzed the data using the constant comparative analysis method (14–16) with support from the qualitative analysis tool NVIVO (version 10; QSR International (U.K.), London, United Kingdom). Qualitative research experts (E.J.M., D.M.D.) developed an initial thematic framework based on the outcomes of preliminary inductive open coding exercises and discussion with five multiprofessional leads. This high-level framework was then applied deductively across the dataset by D.M.D. to further develop and define the emergent themes based on the strength of patterns in the data. The themes were then compared, interpreted, and discussed iteratively in relation to the broader literature on cognition to continuously develop and refine the overall framework. Ongoing discussion with clinical team member (S.J.B.) occurred throughout the analysis process.

RESULTS

Thirty-three hours of qualitative interview data was collected from 44 participants who are described in Table 1. The nurses were all registered. The physiotherapists provided primary support to their ICU site and some support to other clinical areas.

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics by ICU Site, Gender, and Seniority

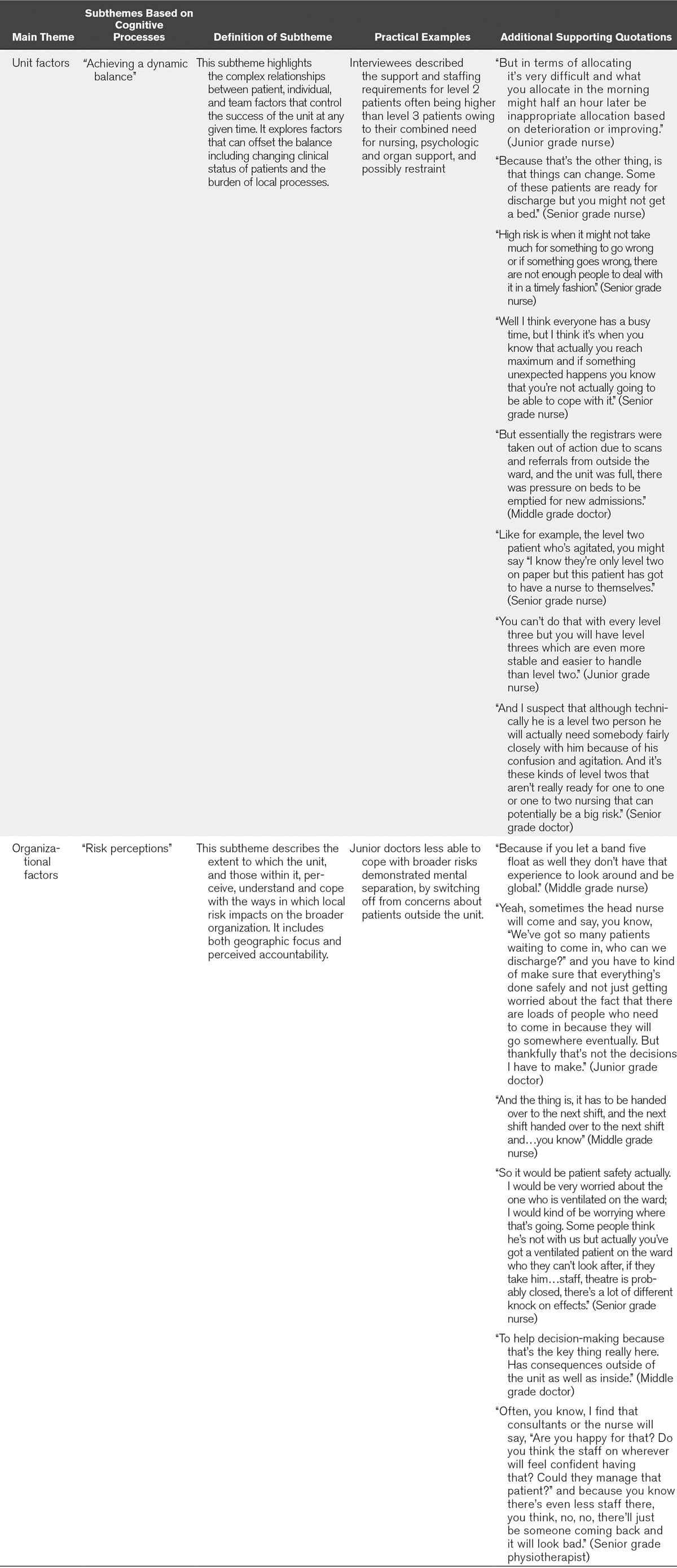

An overview of two themes (individual and team) and subthemes with additional supporting quotations are displayed in Table 2. The remaining two themes (unit and organizational) and subthemes are displayed in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Overview of Individual and Team Themes and Subthemes With Associated Practical Examples and Supporting Evidence

TABLE 3.

Overview of Unit and Organizational Themes and Subthemes With Associated Practical Examples and Supporting Evidence

Individual Staff Factors

The Pragmatist Versus the Perfectionist. Interviewees expressed discrepancies in how they wanted to conduct their work ideally and the reality of how they had to manage their work given the context and circumstances. Some interviewees described either “perfectionist” or “pragmatist” tendencies in themselves and/or others.

Pragmatists had a stronger ability to recognize that compromises might have to be made in order to find solutions and contribute to the collective whole as described by a senior grade nurse, “Of course you have to prioritise, instead of rolling the patient four times it could be done twice or three [times] at the moment, just for example” and a senior grade doctor, “Yeah I’ve got too many patients in the ICU. Then it’s all about figuring out how to fix the problem and there’s always a solution…it may not be the best solution but there’s always a solution.”

Perfectionists, on the other hand, tended to continue to strive for ideal standards for individual allocated patients regardless of competing demands on their attention and resources as described by a senior grade physiotherapist, “I think on a day-to-day working level it’s quite frustrating that we’re not able to provide the input that we want to…..I think it sounds very idealistic but you do go into healthcare to try and help people in some way, and although I do feel I help people I feel I could be doing a lot better.”

Team Factors

Team Dynamics. A predominant finding was interviewees’ personal feelings of security and confidence in team members and the team leader. The concept of “the A team” was adopted to refer to the ideal mix of people in the team on a particular shift. This concept does not just refer to numbers of staff but their length and level of experience, whether they are temporary staff and have worked on the ward before, their existing team relationships, and their level of qualification as described by a junior grade doctor, “I think high risk staffing situations are where you have staff who are inexperienced or who are unskilled, or who don’t have the right skill for the level of patients on the unit or you don’t have enough staff.” When working as part of “the A team,” interviewees described feeling more able to cope with fewer staff members and adapt easily to unexpected situations—as described by a junior grade nurse, “It’s not in terms of skills but I know that there are some people that are more teamwork-orientated than others. So I know that if I come on and look around the room I can feel pretty confident that even if I know we are going to be short staffed that day, with that group of people working around me it’ll be okay because I know that when I ask them for help with something they’ll do it, and I would do the same.”

Linking to the previous individual staff theme, people who are pragmatic and carry on despite difficulties were generally favored as optimal team members by the interviewees. They were sometimes dismissive of team members with perfectionist tendencies who wanted to consistently perform at a high standard and adopt a value driven approach, where this compromised the team effort: “So if I had an A team on, even though we were short staffed, I’d know that they would get on with it.” (Quotation from a senior grade nurse)

Interdisciplinary Tensions. Multiple tensions between different professional groups were played out in the interviews, reflecting the existence of conflicting priorities around patient care and a lack of shared professional goals.

One notable finding was that of prioritization. Doctors described being able to prioritize effectively across numerous patients and situations without becoming emotionally attached to individual cases or circumstances. They were aware of having a high level of responsibility and being unable to “walk away” from competing organizational demands. Nurses, on the other hand, appeared to prioritize differently, associating more closely with individual patients, often making reference to specific cases and situations that they had experienced. Physiotherapists had a different prioritization mechanism, usually prioritizing respiratory patients and discharges over rehabilitation patients. They indicated that they sometimes experienced guilt for dipping in and out of the unit and disrupting the flow of the day for other professional groups. Some interviewees gave examples of trying to adapt their work plans around the existing situation and circumstances of the unit at the time but this was not always in the best interests of the patient and could result in dissatisfaction for multiple parties. A senior grade physiotherapist reflected these tensions, “So sometimes the nurses get a bit cross when you can’t come and sit the patient out of bed now. And you say “well our priority is to get the discharges and the chest patient seen first. Then we can come in the afternoon.” But you see they want to start their day so it’s a bit difficult to get that across” as well as a senior grade nurse, “I think therapists are not necessarily looking at it from the same point of view as we are, because they visit to do their little bit and then disappear.”

A further finding was that of managing emotion and stress. Doctors appeared to manage their emotions differently to nurses. Their interview responses were briefer and relatively objective with respect to clinical decision-making, whereas nurses were more detailed and expansive. Doctors were generally less worried about their own stress levels and instead expressed concern for nurses in particular. This sometimes involved detaching themselves from the emotion of individual cases and taking a wider systems perspective. Nurses were generally aware of their own stress levels (which they felt had potential to impact on their home lives). Nurses reported reassessing and reflecting upon their actions and behaviors toward patients after their shift had ended. A junior grade doctor explained, “Doctors and nurses stress for different reasons and then they don’t really communicate that and then people can get cross and that kind of stuff.”

Unit Factors

The focus of this theme was the requirement for units to continuously manage ongoing fluidity within and across teams, patients, and external organizational factors. It was reported that there is a fine margin between safety and risk on the ICU and only one thing needs to “go wrong,” or change unexpectedly, in order to set off a train of potentially risky events as reflected by a junior grade nurse, “It usually happens in this kind of situation where someone’s needing to go to a scan and then a level two becomes a level three, you know, things you can’t kind of plan for. So someone who maybe was doing a “double” [one registered nurse allocated to look after two patients] one of them has been intubated, so we have to re-jig everyone around to kind of look after them.” Interviewees felt that within the midst of constant pressure it is extremely difficult for staff members to keep everything under control and to juggle multiple issues without negative consequences for themselves or for patients, as described by a junior grade doctor, “So those factors could change; just what appears to be stable might change suddenly and that might need more senior input more urgently.”

Two contributory factors to maintaining a dynamic balance were staff perceptions of the changing clinical status of patients and the burden of local processes. Professional perceptions of patient acuity differed from established regulatory guidelines and tended to develop over time based on experiences, as described by a senior grade doctor, “Yeah I mean I think the level twos are sometimes more demanding than a level three which is ventilated, silent, quiet, so they’re easier sometimes to double them up than level two which can be very demanding.”

Local processes and policy influenced experiences of competing workload demands, risk, and safety, such as not having the option to refuse admission, with the associated difficulties of balancing patient flow; the time spent providing multiple updates to different family members; “excessive” visiting hours in units with very “open” visiting policies; and extensive and difficult processes of documentation.

Organizational Factors

There were differing views as to where the accountability of the individual/team ends (i.e., at the unit or beyond), even where individual’s job roles required them to prioritize patients from the wider hospital. Coping mechanisms were demonstrated where (particularly junior) staff focused in on the unit or individual patient, although their role required a wider focus, and chose not to look outside and take on the responsibility of critically ill patients in other areas (e.g., in theatre, emergency department, deteriorating on the wards) as described by a junior grade doctor, “You know you’ve got to try and separate yourself from what’s going on outside because that would get dealt with, if we just manage the patients we have safely.” This was demonstrated through both physical (e.g., a junior nurse drawing the curtains round the bed to shut off the rest of the unit) and mental separation (e.g., a junior doctor mentally separating themselves by switching off from concerns about patients outside the unit). A senior grade nurse reflected that it “helps to have someone who can take less of a bedside picture and more of a broader picture.” Alternatively, other staff members were better able to assess the risk of patients outside of the unit and juggle priorities in terms of admission. Interviewees that reported feeling able to detach and take a systems view of their work were more aware of how risk could be unintentionally transferred around the organization (i.e., like squeezing a balloon, such as refusing an admission on internal “safety” grounds, who is then cared for by anesthesiology staff in an operating room).

DISCUSSION

The majority of behavioral work in ICU has drawn on human factors (17), systems thinking (11), and the application of nontechnical skills analysis (18) to better understand safety in this clinical context. A less well-researched area is the examination of staff cognitive processes in ICU safety (18). The aims of this study were to 1) examine individual professionals’ perceptions of staffing risks and safe staffing in intensive care and 2) identify and examine the cognitive processes that underlie these perceptions.

Our study identified individual characteristics of pragmatism and perfectionism. Although we found ICU studies that focused on the conceivable consequences of such behavioral inclinations, such as moral distress (19, 20) and “burnout,” (21, 22) few studies explored an underpinning psychologic concept called “cognitive dissonance,” defined as the experiences of individuals when they perform an action, or confront new information that is contradictory to their existing beliefs, ideas, or values (23, 24). We found that clinicians exhibiting perfectionist tendencies from all professions may experience cognitive dissonance in performing their work. This was mainly experienced when the clinician had to perform an action, usually the provision of patient care that was at odds with their beliefs about the optimal level of care that should be given. The impact of cognitive dissonance in this setting is that individuals with perfectionist tendencies may experience greater stress and isolation over time, as the dissonance between their belief system and the practical reality of delivering what they perceive to be compromised care becomes more pronounced. The negative emotion experienced when an individual is in cognitive dissonance can be related to the concept of moral distress in the ICU literature (19, 20) and over time may contribute to “burnout” or change of role (e.g., stopping work in ICU) (21, 22, 25).

Our second finding related to team factors. A body of work exists on the role of team behaviors in the ICU including team working (18), decision-making (18), team coordination (26), and interdisciplinary communication (26–30). In contrast, limited research exists on cognitive processes in ICU, such as the process by which team members’ thoughts and attitudes affect team dynamics and performance (31). We draw upon the concept of psychological safety, a group-level phenomenon to examine issues of team dynamics that we encountered in our study. Psychological safety can be defined as “people’s perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks (such as speaking up or admitting errors) in a particular context such as a workplace” ([32], p. 23) Research evidence indicates that in conditions of high psychological safety, greater knowledge sharing, reflection, engagement, learning, and communication take place (32–35). Participants perceived their ideal “A team” for a shift as comprising individuals they thought had a high level of team orientation. Preferences for “A team” individuals related to having a sense of security and confidence in the person, over external factors such as education, experience, or seniority. This finding suggested that shifts comprising perceived “A team” members are more likely to experience a higher degree of psychological safety than shifts that do not. One component of the team orientation was pragmatism rather than perfectionism, the factor that we found to influence the delivery of patient care at individual level. At team level, pragmatists were perceived to have team priorities uppermost which enabled maintenance of the dynamic balance within the unit.

Research suggests that interprofessional tensions can also compromise or prevent team working and impact negatively on the psychological safety in teams (27, 29, 36). These findings resonated with our study. We found that team-level relationships were complicated by interprofessional tensions that resulted in potentially conflicting priorities. Nurses, doctors, and physiotherapists described different perceptions of care priorities, goal setting, emotional attachment, and stress management. These differences may suggest that, unless actively pursued, authentic team working is unlikely and conflicts may arise around key processes in the unit, such as patient management, admission, and discharge.

Situational awareness (SA) research provided an explanation for our unit-level findings. In simple terms, SA describes an individual’s awareness of the environment around them and has been defined as “the perception of the elements in the environment, within a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status in the near future.” (37) Research in a number of industries suggests that to maintain safety and reduce risk, workers should maintain high levels of SA (38).

We found a high level of SA at unit level, evidenced by participants’ continual reassessment of the patients’ condition. A high level of SA was not only within the immediate clinical situation but, particularly for more senior team members, assessing the patient flow internally and externally to the unit. The “awareness” and “comprehension” elements of SA which translated as knowledge of the patient’s condition, personal experiences of deteriorating patients, and attention to the patient’s current clinical state were evidenced by all grades of staff. The more senior the team member, the more complex the process, as more patients were involved within and beyond the unit. The “projection” element of SA was evidenced through unit planning to achieve the dynamic balance required to manage local processes, including admission and discharge, documentation and supporting relatives, and visitors to the unit. An unexpected and counter-intuitive finding was that some senior individuals responded with anxiety to higher SA, as they became more aware of potential risks and patient safety threats, not only within the unit but across the hospital.

Although there is a body of literature relating to public perceptions of risk (39), the literature on professional risk perceptions in health is limited to specific clinical aspects of risk, for example, genetic testing and smoking cessation in pregnancy (40, 41). We identify a cognitive characteristic, “risk horizon,” which has been developed in other disciplines such as banking (42), but not to our knowledge in the health sector. We define “risk horizon” as the influence of an individual’s risk perception on their interaction with the broader context, that is, the point beyond which an individual feels their personal responsibility to management of safety ends. We differentiate between “near” risk horizons (attention focused on immediate task with attempts to filter out additional potential risks); “midrange” risk horizons (openness to acknowledge risks beyond the immediate task but within the unit); and “far” risk horizons (willingness to balance risks in the unit against those in the rest of the hospital). Instances of physical and mental separation from the unit were evident in individuals describing “near” risk horizons, as mechanisms to “filter out” additional risks. In contrast, certain individuals demonstrated “far” risk horizons, successfully balancing multiple organizational risks, such as patient demand in emergency/operating departments and deteriorating patients on wards alongside high patient acuity within the unit. These external demands were experienced more by middle and senior grade nursing staff, who had to function as shift managers and middle and senior grade physicians who had to attend to patients externally and balance internal and external demands. Physicians in training of all seniorities also tend to run multiple “thought experiments” during which they mentally rehearse hypothetical solutions to problems which they will face once they become more senior decision makers. We expected to find that more senior professionals described “far” risk horizons and vice versa but under situations of stress, even senior professionals occasionally described themselves retreating to “near” risk horizons to cope with immediately stressful situations.

Our qualitative study was undertaken in a U.K. setting, and we recognize the different contexts of British and non-British ICUs (i.e., professional staff profiles and workflows may differ). However, our use of a qualitative design has provided an in-depth exploration of these issues based on a rich dataset. We adopted a purposive sample to ensure adequate participation in the study, while ensuring the sample was representative of professional ratios on the unit. Although the data were generated in the United Kingdom, perhaps these findings can be viewed as challenges for colleagues reflecting on their own local circumstances and offer a starting point for future research on cognitive processes in different settings.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Although we have no empirical evidence to support any particular recommendation, it would seem useful that people in leadership roles in ICU and their team members are aware of the potential heterogeneity of response that can result from individual cognitive processes. We propose a number of practical suggestions to support teams:

1) For ICU leaders, understanding the heterogeneity of response to changing situations in a multidisciplinary team environment should help people manage situations in a nonconfrontational way;

2) Some individuals find SA of events outside the ICU which may impose future stress, as particularly anxiety-provoking; developing scenario-based training exercises that explore these events may assist in developing mutual understanding and broadening individuals’ risk horizon boundaries;

3) Use of table-top scenarios in training sessions to support intensive care teams to develop mutual awareness of roles and responsibilities to manage effectively the dynamic balance on the unit;

4) Explicit institutional management support for individuals required to make compromise decisions;

5) Making use of in-house counselling services to support individuals who feel that the reality of their work does not align with their professional identity, experiencing the burden of cognitive dissonance; and

6) Use of interdisciplinary forums, for example, Schwartz Center Rounds that address the psychosocial aspects of care, can improve the sense of support and decrease work-related stress and isolation that participants may otherwise feel. (29)

CONCLUSION

The aims of this study were to 1) examine individual professionals’ perceptions of staffing risks and safe staffing in intensive care and 2) identify and examine the cognitive processes that underlie these perceptions. Overall there are a number of issues that emerged from this study that we would argue may be generalizable beyond the immediate study context:

1) Some individuals have highly adaptive “pragmatist” tendencies, others tend to be more “perfectionist”; thus, responses to seemingly similar situations may differ, and be a potential source of conflict unless well managed;

2) Staff often have a concept of an “A-team”; their own feelings of resilience and willingness to adapt and take on tasks thus vary depending on who is part of that shift’s team;

3) Although the concept of “SA” is highly promoted- for some people increasing awareness may increase stress and cause, from a team perspective, maladaptive behaviors; and

4) Individuals have varying concepts of where their own responsibility to minimize risk begins and ends—their own “risk horizons” regardless of role—this may change depending on team and environmental factors.

Our results have implications for relationships, management, and leadership in ICUs. Based on our findings, an appreciation of the impact that cognitive processes might have on individual and team behaviors might assist ICU clinicians in determining how to work and lead in teams and manage patient flows effectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the support of Sue Machell and Bernie Brooks from Tavistock Consulting in conducting interviews.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

*See also p. 163.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

Drs. D’Lima and Murray share joint first authorship.

Dr. D’Lima contributed in thematic structure and analysis, writing of first draft, writing of final draft, revision of articles, and approval of final draft; Dr. Murray contributed in original concept and study design, collection of data, thematic structure, writing of first draft and final draft, revision of articles, and approval of final draft; Dr. Brett contributed in original concept and study design, review of emerging themes, revision of articles, and approval of final draft.

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of The Health Foundation, National Institute for Health Research, the NHS or the Department of Health.

Supported, in part, by the National Institute for Health Research comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre, the Patient Safety Translational Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare National Health Service Trust and Imperial College London, and The Health Foundation.

Dr. Murray’s institution received funding from The Health Foundation. Dr. Brett’s institution received funding from The Health Foundation, and he received other support from the National Institute for Health Research Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London (general support for research). Dr. D’Lima disclosed that she does not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, The Intensive Care Society, Royal College of Nursing, Royal College of Speech & Language Therapists, United Kingdom Clinical Pharmacy Association, British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Critical Care Network Nurse Leads, Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, British Dietetic Association, Critical Care Group of the UKCPA: Core Standards for Intensive Care Units. 2013. Available at: https://www.ficm.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Core%20Standards%20for%20ICUs%20Ed.1%20(2013).pdf. Accessed October 11, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 2.British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Critical Care Networks National Nurse Leads, Royal College of Nursing Critical Care and In-flight Forum: Standards for Nurse Staffing in Critical Care. 2009Available at: http://icmwk.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/nurse_staffing_in_critical_care_2009.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams G, Schmollgruber S, Alberto L. Consensus forum: Worldwide guidelines on the critical care nursing workforce and education standards. Crit Care Clin 2006; 22:393–406, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West E, Mays N, Rafferty AM, et al. Nursing resources and patient outcomes in intensive care: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2009; 46:993–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasperino J. The Leapfrog initiative for intensive care unit physician staffing and its impact on intensive care unit performance: A narrative review. Health Policy 2011; 102:223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frankel SK, Moss M. The effect of organizational structure and processes of care on ICU mortality as revealed by the United States critical illness and injury trials group critical illness outcomes study. Crit Care Med 2014; 42:463–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchan J. A certain ratio? The policy implications of minimum staffing ratios in nursing. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005; 10:239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiken LH, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, et al. Effects of nurse staffing and nurse education on patient deaths in hospitals with different nurse work environments. Med Care 2011; 49:1047–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wild C, Narath M. Evaluating and planning ICUs: Methods and approaches to differentiate between need and demand. Health Policy 2005; 71:289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Constantine R, Seth A. Patient Safety. In: Interventional Critical Care. Taylor D, Sherry S, Sing R (Eds). 2016, pp Cham, Switzerland, Springer, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sevdalis N, Brett SJ. Improving care by understanding the way we work: Human factors and behavioural science in the context of intensive care. Crit Care 2009; 13:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krichbaum K, Diemert C, Jacox L, et al. Complexity compression: Nurses under fire. Nurs Forum 2007; 42:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowen GA. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qual Res 2008; 8:137–152. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. 1967New York, NY, Aldine Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss A, Corbin J: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In: Handbook of Qualitative Research. 1994, pp Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, 273–285.. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green J. Commentary: Grounded theory and the constant comparative method. BMJ 1998; 316:1064–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson NB. Integrating behavioral and social sciences research at the National Institutes of Health, U.S.A. Soc Sci Med 1997; 44:1069–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reader T, Flin R, Lauche K, et al. Non-technical skills in the intensive care unit. Br J Anaesth 2006; 96:551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutierrez KM. Critical care nurses’ perceptions of and responses to moral distress. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2005; 24:229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruce CR, Miller SM, Zimmerman JL. A qualitative study exploring moral distress in the ICU team: The importance of unit functionality and intrateam dynamics. Crit Care Med 2015; 43:823–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandevala T, Pavey L, Chelidoni O, et al. Psychological rumination and recovery from work in intensive care professionals: Associations with stress, burnout, depression and health. J Intensive Care 2017; 5:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moss M, Good VS, Gozal D, et al. An official critical care societies collaborative statement-burnout syndrome in critical care health-care professionals: A call for action. Chest 2016; 150:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Festinger L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. 1962Second Edition Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hinojosa AS, Gardner WL, Walker HJ, et al. A review of cognitive dissonance theory in management research. J Manag 2017; 43:170–199. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf LA, Perhats C, Delao AM, et al. On the threshold of safety: A qualitative exploration of nurses’ perceptions of factors involved in safe staffing levels in emergency departments. J Emerg Nurs 2017; 43:150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fackler JC, Watts C, Grome A, et al. Critical care physician cognitive task analysis: An exploratory study. Crit Care 2009; 13:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reader TW, Flin R, Mearns K, et al. Interdisciplinary communication in the intensive care unit. Br J Anaesth 2007; 98:347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas EJ, Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Discrepant attitudes about teamwork among critical care nurses and physicians. Crit Care Med 2003; 31:956–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexanian JA, Kitto S, Rak KJ, et al. Beyond the team: Understanding interprofessional work in two North American ICUs. Crit Care Med 2015; 43:1880–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pronovost P, Berenholtz S, Dorman T, et al. Improving communication in the ICU using daily goals. J Crit Care 2003; 18:71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Proenca EJ. Team dynamics and team empowerment in health care organizations. Health Care Manage Rev 2007; 32:370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edmondson AC, Lei ZK. Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 2014; 1:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siemsen E, Roth AV, Balasubramanian S, et al. The influence of psychological safety and confidence in knowledge on employee knowledge sharing. Manuf Serv Oper Manag 2009; 11:429–447. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edmondson A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q 1999; 44:350–383. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edmondson AC, Higgins M, Singer S, et al. Understanding psychological safety in health care and education organizations: A comparative perspective. Res Hum Dev 2016; 13:65–83. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J Organ Behav 2006; 27:941–966. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endsley MR: Designing for Situation Awareness: An Approach to User-Centred Design. 2004Second Edition Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sneddon A, Mearns K, Flin R. Stress, fatigue, situation awareness and safety in offshore drilling crews. Safety Science 2013;56:80–88. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slovic P. The Perception of Risk. 2000Routledge, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Falahee M, Simons G, Raza K, et al. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of risk in the context of genetic testing for the prediction of chronic disease: A qualitative metasynthesis. J Risk Res 2016:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flemming K, Graham H, McCaughan D, et al. Health professionals’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to providing smoking cessation advice to women in pregnancy and during the post-partum period: A systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Public Health 2016; 16:290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ebnöther S, Vanini P. Credit portfolios: What defines risk horizons and risk measurement? J Bank Financ 2007; 31:3663–3679. [Google Scholar]