Abstract

Nuclear DNA sequences of mitochondrial origin (numts) are derived by insertion of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), into the nuclear genome. In this study, we provide, for the first time, a genome picture of numts inserted in the pig nuclear genome. The Sus scrofa reference nuclear genome (Sscrofa10.2) was aligned with circularized and consensus mtDNA sequences using LAST software. A total of 430 numt sequences that may represent 246 different numt integration events (57 numt regions determined by at least two numt sequences and 189 singletons) were identified, covering about 0.0078% of the nuclear genome. Numt integration events were correlated (0.99) to the chromosome length. The longest numt sequence (about 11 kbp) was located on SSC2. Six numts were sequenced and PCR amplified in pigs of European commercial and local pig breeds, of the Chinese Meishan breed and in European wild boars. Three of them were polymorphic for the presence or absence of the insertion. Surprisingly, the estimated age of insertion of two of the three polymorphic numts was more ancient than that of the speciation time of the Sus scrofa, supporting that these polymorphic sites were originated from interspecies admixture that contributed to shape the pig genome.

Keywords: genome evolution, mtDNA, numt, polymorphism, Sus scrofa

1. Introduction

Eukaryotic genomes have been shaped by the insertion of new sequences of different origin into nuclear DNA, largely influencing their architecture and evolution.1 A particular source of new sequences is provided by the horizontal transfer of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) fragments (from both coding and non-coding regions) into the nuclear genome, producing nuclear DNA sequences of mitochondrial origin (numts).2Numts, which have been frequently discovered inadvertently in the search for bona fide mtDNA3, represent sequence fossils present in the nuclear genome of many eukaryotes, constituting about 0.001–0.1% of its DNA.4 If numts are not recognized in actual mtDNA sequence-based studies, they can compromise result interpretation in detecting heteroplasmy5 or mtDNA pathogenic variants6 or leading to wrong phylogenetic reconstructions.7

The transfer of these genetic materials is however an ongoing, but rare, evolutionary process.8 The exact mechanisms by which mtDNA sequences are integrated into the nuclear genome are not completely understood. The most accepted hypothesis suggests that in presence of mutagenic agents or stress conditions, mtDNA fragments can escape from the mitochondrions and their integration into the nuclear genome could occur during the repair of DNA double-strand breaks.4,9Numts, similarly to other inserted elements, have been used as evolutionary markers by analysing orthologous regions in related species and considering their presence or absence as indications of species radiation times.5,10

Several livestock genomes have been recently analysed to evaluate the presence and distribution of numts. Most of these studies have been based only on genome mining using BLAST search of mtDNA sequence in the available genome versions. Pereira and Baker11 investigated a draft sequence of the chicken genome showing a relatively low number of numts in the avians compared with mammals. Liu and Zhao5 reported a preliminary analysis of the cattle genome using a partial unassembled sequence version. Hazkani-Covo et al.4 interrogated all genomes publicly available at that time (i.e. 2010), including cattle, chicken, rabbit and horse genomes. The horse genome was also interrogated by Nergadze et al.12 who reported polymorphic numts segregating within species.

The Sus scrofa genome has been recently published and the current released version (Sscrofa10.2), available since August 2011, from the Swine Genome Sequencing Consortium (SGSC), accounts for about 3 billions of base pairs.13 The genome of S.scrofa contains signature of inter-species gene flow that indicates reticulate inter taxa crossbreeding events in the constitution of Sus species, involving species of the Island Southeast Asia (ISEA) biodiversity hotspots.14 The domestication processes of S.scrofa occurred independently from European and Asian wild boars whose common ancestors diverged about 1 million of years before present (MYBP).15,16 Then, modern European pig breeds and lines were influenced by the introduction in the XVIII–XIX centuries of Asian blood into European populations.16,17

In this work, we identified and analysed numts in the pig reference genome which, to our best knowledge, is the first comprehensive study in this species that considered mtDNA insertions in the nuclear genome. Phylogenetic analyses provided estimations of numt insertional events during the evolutionary lineage of the Suinae subfamily. We also revealed that polymorphic numts (i.e. presence/absence of insertions) segregate in different pig breeds and can provide interesting signatures to capture reticulate evolutionary events between Sus species and information useful to understand the domestication processes of the pig and the constitution of pig breeds.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Search for numts within the S.scrofa nuclear genome

2.1.1. Data sources

The unmasked reference pig genome was retrieved from Ensembl (Sscrofa10.2, GCA_000003025.4). It includes the porcine reference mtDNA sequence in linear form. Other full-length S.scrofa mtDNA sequences were retrieved from GenBank: these sequences were from different European originated pig breeds (Duroc: the reference mtDNA sequence; Hampshire, AY574046.1; Large White, KC250275.1; Mangalitsa, KJ746666.1) and European wild boar (FJ236998.1) as well as from different Asian originated pig breeds (Jeuma, KP223728.1; Longlin, KM433673.1; Rongchang, KM044239.1; Sandu-black, KM094194.1; Wuji, KM259826.1). A consensus sequence of all ten (European + Asian) mtDNA sequences was obtained by analysing multiple aligned sequences, generated with Multiple Sequence Alignment Tool MUSCLE (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/muscle/), with the CONS software at the EMBOSS-explorer web server (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/emboss-explorer/). Since mtDNA is circular, two linearized mtDNA sequences with the same consensus origin were concatenated to each other, so that subsequent comparison methods could not miss the possibility to identify matches at the beginning or at the end of a linearized single sequence due to boundary effects.

2.1.2. LAST analysis

This concatenated consensus sequence was used to query the reference S.scrofa nuclear genome using LAST software.18 LAST software has been considered to better perform than BLAST in detecting numts as it can be tuned with parameters that can capture low identity expected when aligning old numts to modern mtDNA.18 LAST alignment parameters were: +1 for matches, −1 for mismatches, 7 for gap-open penalty and 1 for gap-extension penalty, that are suitable for detecting distant homology.19 LAST software gives a score based on the expected number of alignments of a random sequence with the same length as the query and a random sequence with the same length as the database. To identify a threshold score for LAST in this approach that minimizes the risk of identifying false positives matches, we followed what was proposed by Tsuji et al.20 using the reversed mitochondrial genome approach. The reversed mtDNA genome was obtained by simply reversing, without complementing, its sequence. This sequence was aligned to the reference nuclear pig genome. Any match between this newly generated sequence and the nuclear genome can be considered to be spurious as DNA sequences do not evolve by simple reversal.20 The number of matches that could be obtained by chance in this test is reported in Supplementary Table S1. A score of 37, which gives an expected probability equal to 0.000734 to identify spurious matches in our analysis, was set as score threshold to identify significant matches.

2.2. Analyses of numt regions

All LAST matches including overlapping sequences or consecutive sequences on the same chromosome were visually inspected using dot plot graphs produced with the ggplot2 R programme (y axis: the mtDNA consensus sequence; x axis: the nuclear genome sequence). Consecutive matches on both axes were considered to identify a numt region derived by a unique insertional event followed by subsequent insertions/deletions of other origin. Other events (i.e. duplications, rearrangements or non-unique insertions) were identified when more complex patterns in consecutive nuclear sequences were evident, compared with the mtDNA sequence (and considered as complex events).

The genomic context of the regions flanking the detected numts was analysed to identify: (i) repetitive elements (1,000 bp from both sides from the inserted numts) using RepeatMasker version 4.0.6 (http://www.repeatmasker.org/); (ii) GC content in the 1,000 bp flanking regions of the numt sequences; (iii) the position of insertion (intergenic, intronic, coding exons, 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions); (iv) the closest annotated gene in the Sscrofa10.2 genome version.

2.3. Identification of polymorphic numt insertions

Blood or muscle samples were used to extract DNA from a total of 66 pigs belonging to 3 commercial breeds (36 Italian Large White, 15 Italian Landrace, 15 Italian Duroc), 77 pigs from 5 Italian local pig breeds (16 Cinta Senese, 16 Mora Romagnola, 17 Casertana, 10 Apulo Calabrese, 18 Nero Siciliano), 13 European wild boars and 6 pigs from the Chinese Meishan breed. DNA was isolated using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer protocols and used for PCR analyses of six selected numts. Numts were chosen considering different criteria: (i) different levels of homology of the numt against the modern mtDNA sequence; (ii) different chromosomes; (iii) possibility to design unique primers (i.e. absense of repetead sequences in the flanking regions, as determid by RepeatMasker version 4.0.6; http://www.repeatmasker.org/); (iv) insertion size of about 200–250 bp to facilitate amplification reactions. Primer3Plus (http://primer3plus.com/web_3.0.0/primer3web_input.htm) programme was used to design PCR primers within about 150 bp of the flanking regions of the six selected numts. PCR primers and PCR conditions are reported in Supplementary Table S2. A 2,720 thermal cycler (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for amplification reactions (the following temperature profile was used: 5 min at 95 °C; 35 amplification cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at the specific annealing temperature reported in Supplementary Table S2, 30 s at 72 °C; 5 min at 72 °C) that were carried out with the Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, on a 20 µl final reaction volume that contained about 50 ng of template porcine DNA. Amplified fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels and visualized with 1× GelRed Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Biotium Inc., Hayward, CA, USA). Amplicons obtained from all primer pairs for at least six different animals were used for Sanger sequencing. Amplified fragments from homozygous animals were purified from the PCR reactions using ExoSAP-IT (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH, USA) or ethanol precipitation. Fragments from heterozygous animals were isolated from gels cutting the band of interest that was purified with the Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Purified fragments were sequenced using the BrightDye Terminatior Cycle Sequencing Kit (Nimagen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands), and loaded on ABI3100 Avant capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All sequences were visually inspected and aligned with the help of CodonCode Aligner (version 5.1.5) software (http://www.codoncode.com/aligner/). Obtained sequences were aligned to the Sscrofa10.2 reference genome or to the expected numt flanking regions without numt insertion using BLASTN.

2.4. Phylogenetic analyses

An ancestral mtDNA sequence was inferred using all publicly available and complete mtDNA sequences of Suinae species (subfamily of the Suidae family) that diverged about 10 MYBP.21 Sequences were from: Phacochoerus africanus (GenBank accession number: DQ409327), Potamochoerus porcus (JN632688), S.scrofa (mtDNA from Sscrofa10.2 reference genome), Sus celebensis (KM203891), Sus cebifrons (KF952600), Sus verrucosus (KF926379), Sus barbatus (KP789021). mtDNA sequences were aligned as described above and the consensus sequence was obtained with the CONS software (see above). The age of each numt inserted in the Sscrofa10.2 genome version was calculated according to Dayama et al.23 as follows: (i) each numt sequence was aligned to the previously aligned ancestral Suinae and modern mtDNA sequences; (ii) the total number of sites in the aligned regions where the ancestral and modern mitochondrial sequences differ were counted (ancestral_vs_modern); (iii) of these variable positions, the numt sequence that matched the modern mtDNA sequences was tabulated (numt_vs_modern); (iv) the allele matching ratio (amr) was calculated: amr = (numt_vs_modern)/(ancestral_vs_modern), and used to estimate when the insertion occurred along the Suinae lineage (insertion before present, ibp), considering 10 MYBP its divergence period, as follows: ibp = (1 – amr) × 10, expressed in MYBP. Numts that contained D-loop sequences were not used for age estimation due to their uncertaintly in predicting ancestral D-loop sequences. The ibp was also computed for numt regions derived by unique insertional events (defined earlier) by summing, for the different LAST matches, numt_vs_modern and ancestral_vs_modern to obtain a single allele matching ratio for each numt region. Phylogenetic trees were obtained for the validated numt (Table 1) and the largest numt insertions (>500 bp). Numt sequences were aligned (using MUSCLE software) with the corresponding mtDNA sequence of all Suinae species reported earlier in addition to the mtDNA sequences of Pecari tajacu (Tajassuidae species, Suidae; accession number AP003427) and Bos taurus (AY526085), downloaded from GenBank. Trees were built with MEGA 7.0.1822 using Maximum-Likelihood method (applying default options) with 1,000 bootstrap values.23Supplementary Material S1 includes sequences used for the phylogenetic analyses. To evaluate the presence of ancient numt insertions in the genome of first closest species to the pig for which an annotated genome is available (the cattle genome, UMD3.1 genome version), LAST analysis (with the B.taurus mtDNA sequence indicated above and using parameters described for the mining of the pig genome) was carried out in the cattle genome. Numt insertions were declared orthologous by comparative mapping analysis using annotated regions in the two pig and cattle nuclear genomes and by veryfing the insertion of homologous mtDNA regions in two species using BLASTN.

Table 1.

Characteristics of investigated numt sequences

| Numt IDa | Numt length (bp) | Identity with the modern mtDNA (%) | No. of diagnostic positions | No. of positions matching modern mtDNA | Estimated age of insertion (MYBP)b | Polymorphismc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3_15 | 207 | 99 | 3 | 3 | <0.5 | Yes |

| 4_19 | 218 | 89 | 3 | 1 | 6.7 | No |

| 8_10 | 214 | 92 | 4 | 2 | 5 | Yes |

| 13_32 | 202 | 90 | 6 | 2 | 6.7 | Yes |

| 15_09 | 239 | 86 | 6 | 0 | 10 | No |

| 16_02 | 228 | 93 | 0 | 0 | nc d | No |

aDetails of numt sequences are reported in Supplementary Material S3. The first number indicates the porcine chromosome in which the corresponding numt is inserted. The second number is a progressive count of numts sequences in the indicated chromosome.

bCalculated considering MYBP: millions of years before present.

cPresence or absence of the numt insertion in one or more pig breeds.

dNot calculated. This alignment did not contain any informative site for this estimation.

2.5. Data release

All new sequences have been submitted to EMBL/GenBank databases with accession numbers from LT707410 to LT707414. Numt annotation of the Sscrofa10.2 genome version is available as GFF file as Supplementary Material S2. GFF annotation is also available through the Dryad database (http://datadryad.org/).

3. Results

3.1. Identification of numt sequences in the pig nuclear reference genome

Mining the assembled and the unassembled (scaffolds) of the nuclear reference genome Sscrofa10.2 with LAST and a consensus modern mtDNA sequence obtained from European and Chinese pigs, we identified 401 and 29 significant matches (LAST score >37), respectively, belonging to numt sequences (Supplementary Material S3). Identity of these matched nuclear sequences with the modern mtDNA sequence ranged from 60 to 100% (mean of 78%). The lower value may indicate the detection limit of our approach. Distribution of numt sequences according to their size is presented in Table 2. Numt sequence lenght varied from 42 to 4,782 bp with an oulier of about 11 kbp integrated on porcine chromosome (SSC) 2, with 90% identity with the modern porcine mtDNA sequence.

Table 2.

Summary table of detected numt sequences according to their size range

| Number | Size range (bp) | Similarity range (%) | MYBPa range | Average MYBP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 59 | 40–99 | 78–100 | 0–10 | 7.25 |

| 130 | 100–249 | 65–100 | 0–10 | 7.02 |

| 83 | 250–499 | 62–92 | 0–10 | 7.03 |

| 52 | 500–749 | 60–94 | 0–10 | 6.76 |

| 27 | 750–999 | 36–98 | 0–10 | 6.62 |

| 39 | 1000–1999 | 63–95 | 2.5–9.4 | 7.19 |

| 10 | 2000–4999 | 67–90 | 5.8–8 | 7.03 |

| 1 | >5000 | 90 | 7.6 | 7.57 |

aMillions of years before present as reported in Supplementary Table S3.

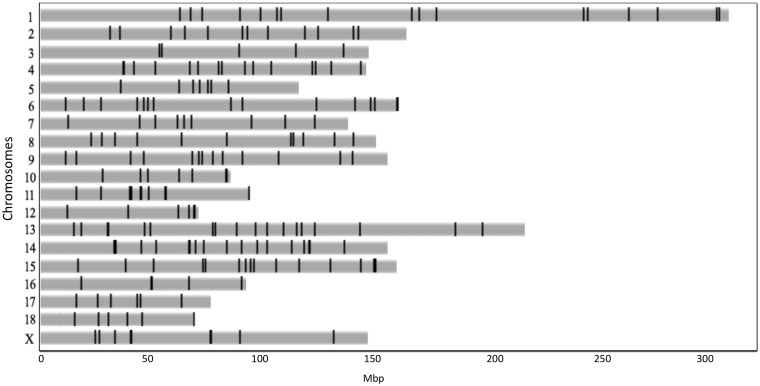

All these numts accounted for a total of 0.0078% of the nuclear porcine genome (a total of 217,848 bp). Table 3 and Fig. 1 show the distribution of numt sequences in the different porcine chromosomes and their positions. Porcine chromosome (SSC) 14 showed the largest proportion of numts (∼0.02% of its size was covered by these sequences with also the largest number of detected numt sequences; n = 60) whereas SSC5 was covered by the lowest proportion of these integrated nuclear mtDNAs (∼0.001%). There is a modest linear relationship between the number of numts located on each chromosome and their relative length (Pearson’s r = 0.65, P-value = 0.003). The average distance between two close numts in the reference porcine genome is 6.5 Mbp (ranging from a few bp to 70 Mbp).

Table 3.

Numt sequences in the pig nuclear genome

| SSC | No. of numtsa | Total numt sequences (bp) | Total numt sequences (% on the SSC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37; 21 (28) | 14,299 | 0.004535 |

| 2 | 28; 15 (14) | 27,824 | 0.017115 |

| 3 | 28; 5 (13) | 23,385 | 0.016151 |

| 4 | 20; 17 (13) | 5,169 | 0.003603 |

| 5 | 9; 9 (10) | 1,169 | 0.001048 |

| 6 | 30; 17 (14) | 12,196 | 0.00773 |

| 7 | 10; 9 (12) | 1,463 | 0.001086 |

| 8 | 18; 13 (13) | 12,897 | 0.008665 |

| 9 | 25; 15 (14) | 13,853 | 0.009015 |

| 10 | 17; 6 (7) | 9,670 | 0.012225 |

| 11 | 11; 11 (8) | 2,219 | 0.00253 |

| 12 | 11; 6 (6) | 3,676 | 0.005781 |

| 13 | 35; 19 (19) | 13,951 | 0.006381 |

| 14 | 60; 20 (14) | 31,592 | 0.020534 |

| 15 | 23; 16 (14) | 9,954 | 0.006313 |

| 16 | 5; 5 (8) | 983 | 0.001131 |

| 17 | 11; 8 (6) | 8,443 | 0.012113 |

| 18 | 7; 6 (5) | 1,512 | 0.00247 |

| X | 16; 12 (13) | 15,987 | 0.01108 |

| Unb | 29; 16 | 7,606 | — |

| Total | 430; 246 | 217,848 | 0.00776 |

aNumber of numt sequences determined by LAST; number of numt integration events as defined in the text; in parenthesis: expected number of numt integration events, considering equal distribution across the nuclear genome (rounded numbers without any decimals).

bUnassembled scaffolds.

Figure 1.

Distribution of numts in the pig nuclear genome. Numt positions are represented in the Sscrofa10.2 assembled chromosomes.

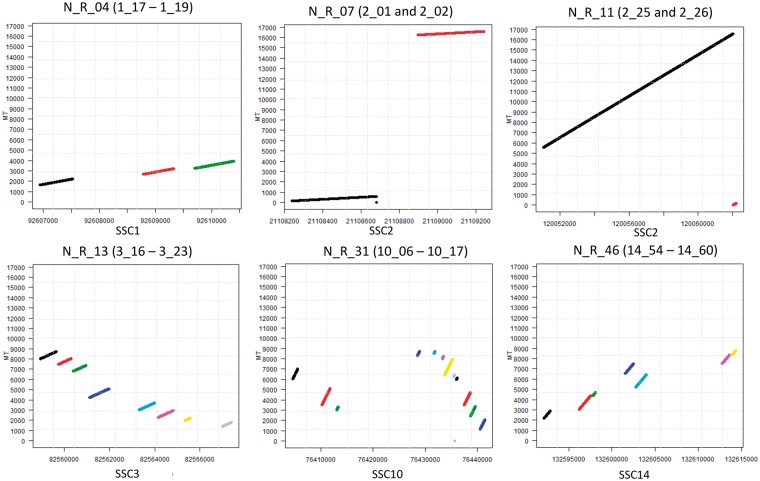

Close numt sequences could identify unique insertional events into the nuclear genome that underwent subsequent deletions or insertions (and/or other complex rearrangements) separating contiguous mtDNA regions that we however identified as separate numt sequences using LAST. To evaluate this issue, we dot-plotted all nuclear regions including numt sequences separated by up to 20 kb against the modern mtDNA sequence. We then called independent numt regions (derived by unique numt insertional events) according to the possibility to infer contiguity based on the integration of mtDNA sequences into the nuclear genome. Other numt regions included complex rearrangements or duplications that could not be possible to consider as derived by one or more than one insertional event. Figure 2 shows a few examples of numt regions that could be described as derived by unique insertional events or that could be considered as complex numt regions, including duplications and rearrangements. Of the total 430 numt sequences that matched the modern mtDNA sequence with LAST, using the dot plot approach we could identify 57 numt regions including at least two numt sequences (54 numt regions in the assembled reference genome and 3 in the unassembled scaffolds) and 189 singleton numt sequences, accounting for a total of 246 separated numt integrations in the reference porcine nuclear genome. Of these 57 numt regions, 51 were considered as derived by independent insertional events and 6 were defined as complex numt regions. Detailed information on all numt regions and putative independent integrations are reported in Supplementary Material S3. Linear relationship between the number of numt integrations located on each chromosome and their relative length increased substantially (Pearson’s r = 0.99, P-value < 0.001). The average distance between two close numt integrations in the reference porcine genome is 11.3 Mbp.

Figure 2.

Dot-plot analysis of a few numt regions. Numt region ID and numt sequences are reported at the top of each plot. The X axis reports the positions in the indicated chromosomes. The Y axis reports the mtDNA sequence coordinates. Details of these regions are reported in Supplementary Table S3. Different coloured lines in the plots indicate different numt sequences.

As the accuracy of the assembly of the available pig reference genome (Sscrofa10.2) is limited, it could be possible that a few numts derive by misassemblies. However, as almost all numt sequences had identity lower than 100% (similarity ranged from 60 to 100%, median similarity was 77%) with the modern porcine mtDNA (indication of evolutionary divergence), it seems plausible to exclude assembly errors that would have included true mtDNA fragments into the nuclear genome. The only two short numts with 100% identity with the modern mtDNA are compatible with a recent insertion into the nuclear genome (Supplementary Material S3). Other sources of misassemblies could have been produced by duplications of numt sequences even if a close inspection of the results did not identify any obvious problem originated by duplicated regions of the porcine genome.

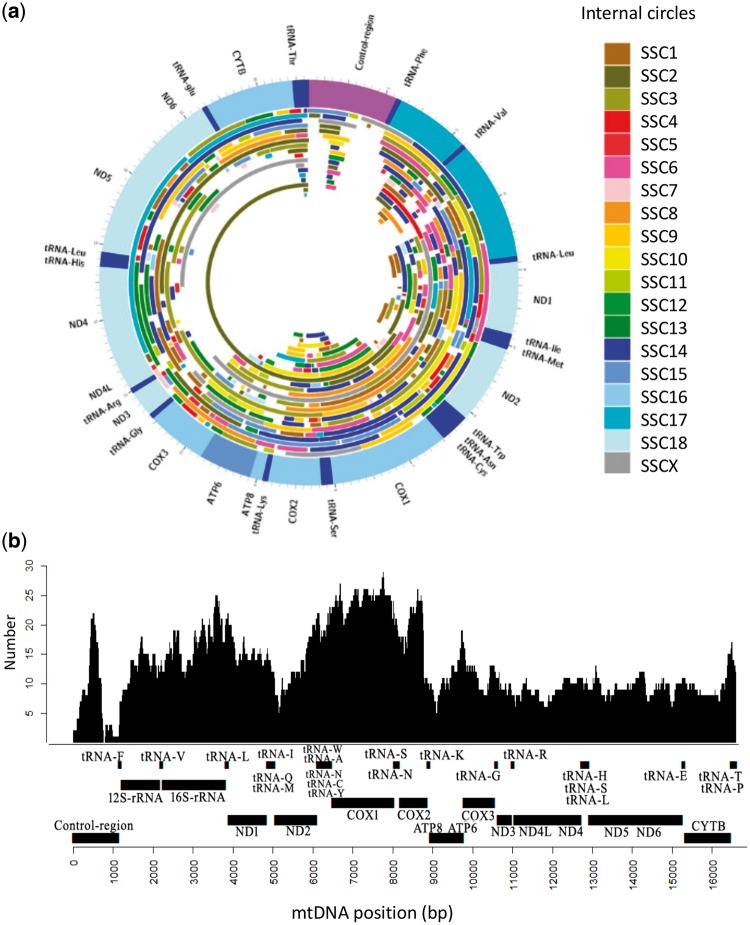

Figure 3 shows (i) the distribution of numts along the circularized mtDNA genome with indications of nuclear porcine chromosome in which the corresponding numt was integrated (Fig. 3a) and (ii) the distribution of numt hits in the linearized mtDNA sequence at the different nucleotides (Fig. 3b). If we just exclude the variable repeated region of the control region, for which alignments were problematic due to highly variable number of repeats, all mtDNA regions were covered at least once by numt sequences (Fig. 3b). The most covered mtDNA regions by numts included parts of the COX1, COX2 and 16S-rRNA genes. It was also interesting to note that the D-loop of the control mtDNA region, a non-coding region of the mitochondrial genome that controls the synthesis of DNA and RNA within the mitochondria and that usually exhibits a higher mutation rate than the other regions of the mtDNA, was covered by 34 numts.

Figure 3.

(a) The porcine mtDNA with numts plotted along its circular structure. Numts are coloured according to the porcine chromosomes in which they are inserted. Mitochondrial genes are reported in the outer ring. (b) Coverage of the linearized porcine mtDNA with numts. The number of numt copies are plotted in the ‘Y’ axis. The mitochondrial genes are reported in the ‘X’ axis.

3.2. Characteristics of numt insertion regions

Numts were found to be slightly preferentially inserted in regions with higher GC content (flanking regions have a GC% equal to 42%, compared with the overal GC content of the pig nuclear genome that is 39%). RepeatMasker analysis of the numt flanking sequences determined that only 8% (64 cases out of all 802 flanking regions analysed) includes non-repetitive sequences. Therefore, most numt flanking regions contain repetitive elements (Supplementary Material S3). The most frequent reported repetitive elements were short interspersed nuclear elements or SINE (48% of numts are nearby SINE elements). The second most frequent repetitive elements were long interspersed nuclear elements or LINE (24%). The overall SINE and LINE content of the pig genome is 11 and 16%, respectively,13,24 therefore it is clear that numt sequences are preferentially located near or within repetitive elements in the S.scrofa genome (P < 0.0001, chi square test).

A total of 57 numt sequences out of 430 numts detected in the S.scrofa genome (from 51 different numt regions or singletons) were located within 49 different annotated genes. All numts were in intronic regions. All other numt sequences were located in intergenic regions. Details on the closest gene to all detected numts (as annotated in Sscrofa10.2) are reported in Supplementary Material S3. Gene functional enrichment of the closest annotated gene to all identified numts did not identify any enriched function or features (data not shown).

3.3. Validation of numts and identification of polymorphic numts (presence/absence of insertion)

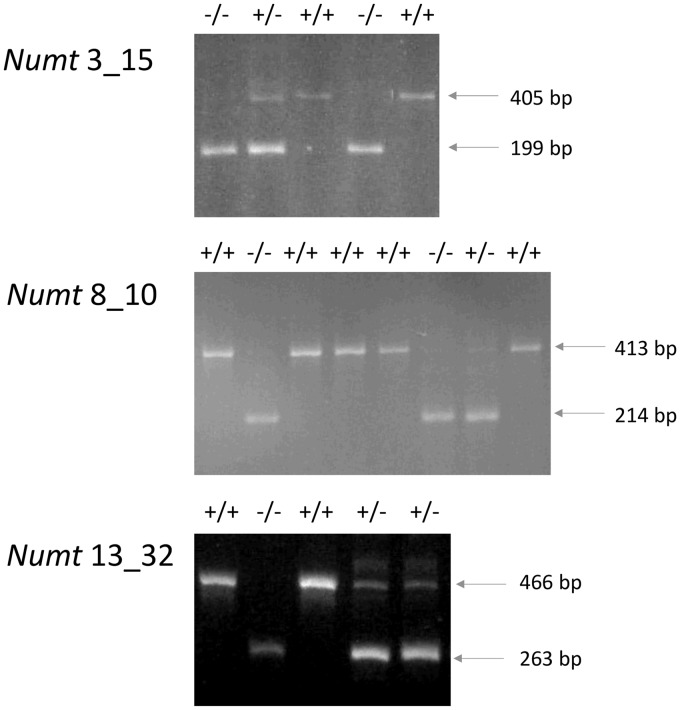

Six primer pairs were designed to validate the presence of numt insertions in pigs belonging to Chinese (Meishan) and Euro-American pig breeds (three commercial and five local breeds) and European wild boars. At the same time these primers could verify if polymorphic numt regions derived by the presence of absence of the inserted numt could be detected from this panel of animals. Features of the amplified numts are reported in Table 1. Three primer pairs designed for numts 4_19 (identity with the corresponding modern mtDNA: ∼87%), 15_09 (identity: ∼86%) and 16_02 (identity: ∼93%), respectively, produced the expected fragment size (Table 1, including the inserted numt sequence as confirmed by sequencing) in all analysed pigs across all breeds and European wild boars. Amplifications obtained for three other numts (3_15, identity: 99%; 8_10, identity: 92%; and 13_32, identity: 90%) showed fragments of lower size than that expected (Fig. 4). Sequences of these fragments confirmed the absence of numt sequences in these amplicons (EMBL accession numbers: LT707411 for numt 3_15; LT707414, for numt 8_10; LT707412 for numt 13_32; see Fig. 5 for the sequence alignments between genomic regions with the presence and the absence of the numts).

Figure 4.

Electrophoretic patterns of amplified numt regions (3_15, 8_10 and 13_32) showing polymorphisms determined by the presence or absence of numt sequences. ‘+’ indicates the presence of insertion; ‘−’ indicates the absence of the insertion. The genotypes are reported at the top of each gel picture. The number of pigs with the three different genotypes for each numt loci is reported.

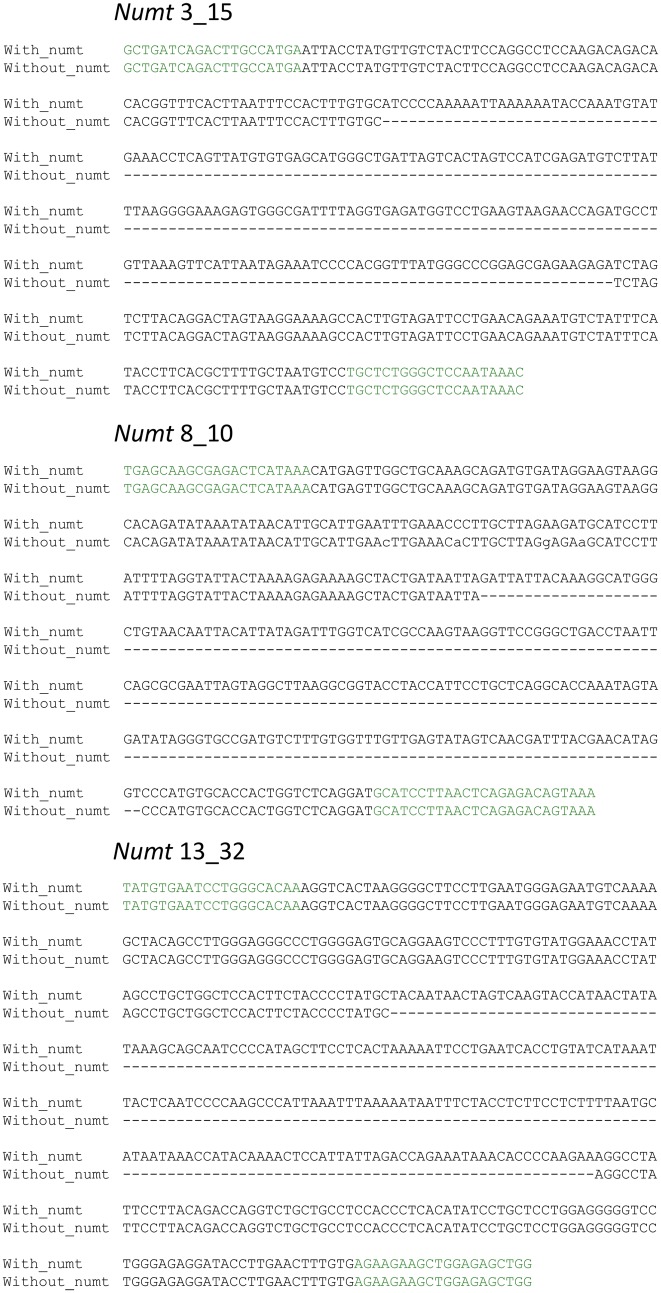

Figure 5.

Alignments of regions including numts versus the same regions without numts, when polymorphic. The sequence indicated as ‘with_numt’ is identical to the Sscrofa10.2 reference region, the sequence defined as ‘without_numt’ indicates the sequence obtained by Sanger sequencing of the fragments that do not include the numt (Fig. 4). These regions where polymorphic in the population and their sequence were submitted in EMBL database with the following accession numbers: Numt 3_15, LT707410 with numt, LT707411 without numt; Numt 8_10, LT707410 with numt, LT707411 without numt; Numt 13_32, LT707412 without numt, the sequence with numt is the same present in Sscrofa10.2. Primer regions used for the amplification are included in the reported sequences: see Supplementary Table S2 for the black and white version to identify the primer sequences; primer regions are highlighted in green in the online colour picture.

Distribution of polymorphic numts is reported in Table 4. For numt 3_15, polymorphic insertions (i.e. presence of two alleles: one with the numt sequence and one without this insertion) were observed in two local pig breeds (Apulo Calabrese and Nero Siciliano, with two genotypes only) and in the Chinese Meishan, with the same frequency of all three genotypes in just six animals analysed. All other breeds were fixed for the insertion allele. For numt 8_10, presence/absense polymorphism was observed in Italian Large White, Italian Landrace, Italian Duroc and Nero Siciliano breeds in which the insertion allele was always the most frequent. All other breeds were fixed for inserted allele. Polymorphism derived by the presence/absence of the numt 13_32 was observed in Meishan and Italian Large White pigs in which the absence of insertion allele was the most frequent or was close to 50% and in three local breeds (Cinta Senese, Apulo Calabrese and Nero Siciliano) in which the insertion allele was far the most frequent. In all other breeds, the insertion allele for numt 13_32 was fixed. All European wild boars investigated were homozygous for the insertion allele at al three numt loci.

Table 4.

Numt insertion polimorphisms for three numt loci (3_15, 8_10 and 13_32) in different pig breeds and populations

| Breed/population | No. of pigs | 3_15 |

8_10 |

13_32 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | −/+ | −/− | +/+ | −/+ | −/− | +/+ | −/+ | −/− | ||

| Italian Large White | 36 | 36 | — | — | 24 | 8 | 4 | 13 | 12 | 11 |

| Italian Landrace | 15 | 15 | — | — | 14 | — | 1 | 15 | — | — |

| Italian Duroc | 15 | 15 | — | — | 8 | 3 | 4 | 15 | — | — |

| Cinta Senese | 16 | 16 | — | — | 16 | — | — | 15 | — | 1 |

| Mora Romagnola | 16 | 16 | — | — | 16 | — | — | 16 | — | — |

| Casertana | 17 | 17 | — | — | 17 | — | — | 17 | — | — |

| Apulo Calabrese | 10 | 7 | — | 3 | 10 | — | — | 9 | 1 | — |

| Nero Siciliano | 18 | 17 | 1 | — | 13 | 4 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 2 |

| European wild boar | 13 | 13 | — | — | 13 | — | — | 13 | — | — |

| Meishan | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | — | — | 1 | 2 | 3 |

‘+’ indicates the presence of insertion; ‘−’ indicates the absence of the insertion. The number of pigs with the three different genotypes for each numt locus is reported.

3.4. Phylogenetic analysis of numts

We estimated when the insertional events occurred in the Suinae lineage by comparing modern mtDNA sequences with a consensus Suinae mtDNA sequence and identifying diagnostic sites in the numt sequences. Table 1 reports the estimated age of insertion of validated numts. Information for all numts (for which alignments and detection of diagnostic sites were possible) is reported in Supplementary Material S3. Age of numts ranged from 10 MYBP (the back limit of our approach derived by the use of a Suinae consensus sequence used to identify informative nucleotides) to very recent integration times (<0.5 MYBP). The largest numt spanning about 11 kb of the modern mtDNA, located on SSC2, was estimated to be inserted in the porcine nuclear genome about 7.7 MYBP (numt 2_25 in Supplementary Material S3). Phylogenetic trees placed more divergent numt sequences (identity <80% with the modern mtDNAs) before the Tajassuidae lineage separation or even out from the B.taurus root. Confirmation of the presence of orthologous numt sequences in the bovine genome was obtained by comparing numts identified within the regions that are syntenic between S.scrofa and B.taurus genomes. Orthologous numts are reported in Supplementary Material S3 with their respective bovine nuclear and mitochondrial coordinates. Five of them, namely 9_09, 10_10, 15_15, 18_05 and 18_06 were located within the orthologuos bovine genes (within the same intron), and in both species with identity from 63 to 71%, further indicating that the insertion was not recent and originated by a unique event that occurred in a common ancestral genome.

Results of phylogenetic analyses for the polymorphic numts indicated that the range of insertion age spanned a surprisingly large period of time if referred in the Suinae evolutionary line. In particular, all diagnostic sites of numt 3_15 were present in the modern mtDNA suggesting that its insertion was recent (below the resolution time of 1 MYBP) and probably after the separation of the common ancestral wild boar lineage from which the Asian and European pigs were domesticated. Phylogenetic tree reconstruction confirmed the recent insertion of this numt (Fig. 6). As most of European breeds are fixed for this insertion (Table 4), we could speculate that this numt was inserted during the European evolutionary differentiation within the S.scrofa species. Insertion of this numt might derive from a European wild boar ancestor of this lineage. Then this polymorphic site could have been introgressed into Asian domestic breeds as Meishan pigs show both alleles (presence and absence of the insertion).

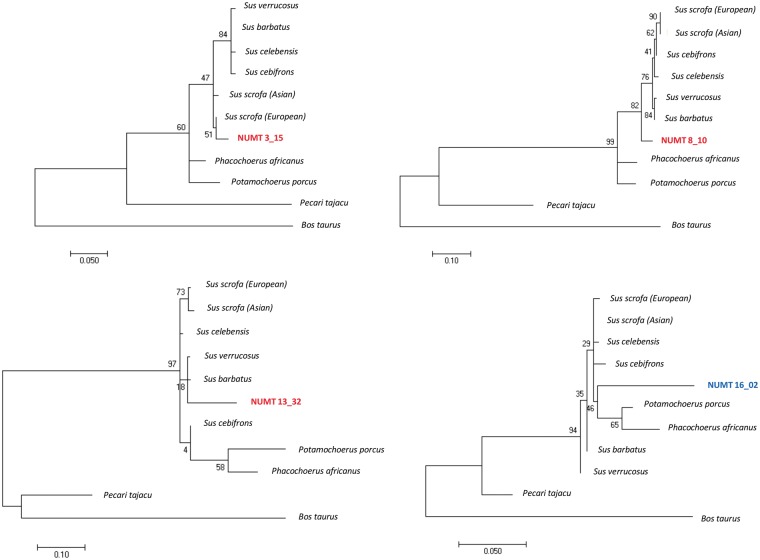

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic trees of four numt sequences reported as examples, three of which (numts 3_15, 8_10 and 13_32, indicated in red in the trees) were the polymorphic numts. The number at each node indicates the bootstrap frequency.

Numt 8_10 was estimated to be inserted about 5 MYBP (Table 1) as also confirmed by the phylogenetic tree analysis that placed it before the separation of all considered Sus species (Fig. 6). As Meishan breed was fixed for the inserted allele and all commercial European domestic pig breeds were polymorphic at numt 8_10, it is possible to speculate that the absence allele was introgressed into European populations from Asian pigs, that in turn might have acquired the old allele (absence of the numt sequence) from interspecific admixture with other Sus species living in the ISEA closely in contact with Sus species of the Mainland Southeast Asia (MSEA). This interspecific gene flow may explain the age of this numt and at the same time the fact that it is not fixed in the S.scrofa (as it might be considering the estimated age before the Sus lineage differentiation).

Estimation of the insertion age for numt 13_32 indicated about 6.7 MYBP. The topology of the phylogenetic tree including this numt was more difficult to be interpreted according to the evolutionary relationships between the Sus and the other Suinae taxa included in this study (Fig. 6). This might be due to differences in information content of different parts of the mtDNA. The position of numt 13_32 however may indicate an ancient integregation age that probably occurred before the separation of the Sus species (late Miocene/early Pliocene). In addition, the presence of polymorphisms in both modern European and Asian S.scrofa breeds and populations (Table 1) might indicate again a possible introgression of the ‘absence’ allele of putative Asian origin (not fixed in Asian breeds) into European domestic pigs, similarly to what might have been happened for numt 8_10.

4. Discussion

Evolution of eukaryotic genomes has been affected by the acquisition of new sequences of many different origins into the nuclear DNA. For example, in mammals mobile or transposable elements (the most important class of acquired elements) accounts for nearly half of their genomes1. The role and impact of the insertion of LINE and SINE and retroviruses into the nuclear genome have been investigated in many species, including farm animals. These insertions could be particularly relevant when genes were targeted, contributing to define novel functions and structures.25 Inserted elements may also provide phylogenetic information among related species, considering their ancient signature derived by their integration position (uniqueness) in an ancestral genome.26,27 This ancestral signature has been used to reconstruct the history of domestication in animals.28 In humans, model animals and livestock species, more recent mutagenic insertional events, polymorphic within species, have been reported to cause a number of diseases and novel phenotypes.29–31

Most of the eukaryotic genomes so far analysed have demonstrated the presence of mtDNA sequences into the nuclear genome.4 As expected, also for the S.scrofa nuclear genome we reported evidence for the transfer of mtDNA to the nuclear genome. The fraction of the ‘contaminated’ nuclear genome of the pig (0.0078%) is within the range already observed in several other mammals. For example, the percentage of the nuclear human and cattle genomes covered by numts was reported to be 0.0087 and 0.0023%, respectively.4 A few differences among studies carried out within the same species (e.g. humans) might be due to different mining approaches and applied thresholds to declare homology between nuclear DNA and mtDNA sequences.4,20 Following what was suggested by Tsuji et al.,20 who mined the genome of several mammals to find numts, we used the LAST programme to perform local sequence alignments instead of BLAST. Also in our hands, LAST was able to identify a larger number of numt sequences compared with BLAST (a total of 89 BLAST hits were identified in the Sscrofa10.2, e-value < 0.001) that did not capture more divergent sequences derived by ancient integrations (that underwent several mutational differentiation processes) or complex rearrangements (data not shown).

Dot-plot analysis of numts indicated that a quite large number of porcine numt sequences could be derived by a single insertional event that subsequently underwent additional mutations as part of the evolutionary processes of the nuclear genome. A total of 247 separated insertional events (with 56 numt regions derived by more than one numt sequence) could be inferred after this close inspection of the inserted nuclear genomic regions. This analysis indicated that most of the complex numt regions were derived by nuclear mutations that split the integrated mtDNA in separated but co-linear regions with a few exceptions that included more complex rearrangements with duplications and invertions (Fig. 2). Most of the complex numt regions were estimated to be caused by very ancient mtDNA integration events in the nuclear genome of this species (at least 10 MYBP that is the back limit defined by our consensus mtDNA sequence).

All mtDNA regions were present in porcine numts, including D-loop sequences. Tsuji et al.20 suggested that the D-loop region is under-represented in human numts as a specific effect of numt integration bias of the primate evolutionary lineage. This might not be true for the pig genome in which a quite large number of numts covered these highly polymorphic mtDNA regions. As this porcine mtDNA region has been used several times in population genetic studies and phylogenetic analyses16,32 due to the presence of frequent informative polymorphisms, it will be important to carefully evaluate if unintentioned amplified numts could have been a source of unexpected variability in supposed mtDNA sequences. This problem could be relevant not only for the D-loop region but also for all other informative mtDNA regions used for different purposes. A recent analysis of livestock mtDNA sequences deposited in DNA databases33 reported that of 127 near complete porcine mtDNA sequences available in GenBank, about 32% contained errors. For almost half of these problematic sequences the surplus of mutations observed in these entries was probably due to contamination from numt sequences. This problem might be also present in many other partial porcine mtDNA sequences deposited in public databases. As numts are not under strong selective constrains of the mitochondrial genome, they might usually contain pseudogene signatures (if they come from protein-coding regions) that can be used to distinguish them from true mtDNA sequencs (i.e. frameshift mutations, premature stop codons, inserions and deletions). However, recent transferred sequences that have not accululated these characteristics yet and numts from non-coding mtDNA regions might be more cryptic to be detected.7 A closer inspection of this possible source of biases in mtDNA studies can be now possible using as reference the porcine numt sequences we identified.

Insertion position of porcine numts seems to co-localize with two classes of retrotransposon sequences (i.e. SINE and LINE). Similar co-localization on repeated regions has been reported for numts in a few mammalian genomes including the human genome,20,23 further confirming a general feature that shapes the distribution of numts in mammals. The precise mechanism by which this occurs is not understood yet. This more frequent co-localization feature can hold even if the position of numts in the reference porcine genome (as well as in all other analysed mammalian genomes) may reflect a non-random sample of numt insertion events that were probably filtered out from deleterious events. This is true considering that only a fraction of the mammalian genome (10–15%) is functional34 and may accept the introduction of novel DNA during its evolutionary processes. All detected porcine numts were inserted in intergenic regions (n = 195) or in intronic regions (n = 51) and a potential functional role of these insertions was not obvious. Althought in most cases these insertions might be neutral, it could be possible that in rare cases numts are inserted into genes as already described in humans, producing genetic diseases or altered phenotypes.35–38 Additional S.scrofa genomes might be investigated to identify other numts not present in the reference genome version used in this study. Dayama et al.23 showed in humans that more recent numt sequences could be discovered when other genomes were analysed for the presence of this type of new sequence integration in the nuclear genome.

Polymorphic numts (i.e. presence or absence of the inserted mtDNA sequence) were identified to segregate in different pig populations. The presence of allelic numt loci within a species might usually indicate a very recent origin of the insertion events, i.e. after the speciation process. This is what was observed in humans23 and horse,12 the only other two species in which this phenomenon has been described so far. Surprisingly, the estimated age of insertion of two of the three polymorphic numts was more ancient than that of the speciation time of the S.scrofa. The insertion ages of numts 8_10 and 13_32 were estimated to be about 5 MYBP (early Pliocene) and about 6.7 MYBP (late Miocene), respectively, i.e. before the differentiation of the Sus genera or just after the constitution of this lineage. Even if our estimation could not be very precise as it is based only on a few diagnostic mtDNA positions, it seems clear that these insertions were not recent (as also confirmed by the general identity of the two numts with the modern mtDNA: 92 and 90%, respectively). This estimation however contradicts the fact that these numt insertions were not fixed in S.scrofa species. Of the genus Sus, all extant species except S.scrofa (spread across all Euro-Asian regions) are restricted to ISEA region (S.barbatus: in Borneo, Malay Peninsula and Sumatra; S.verrucosus: in Jawa and Bawean; S.cebifrons and Sus philippensis: Philippines; S.celebensis: Sulawesi). Frantz et al.14 demonstrated that the evolutionary history of Sus species can be better explained by a reticulate history derived by many episodes of interspecies admixture. Ai et al.39 reported the presence of a peculiar divergent region, spanning several megabases on SSCX, differentiating southern domestic Chinese breeds (more similar to ISEA species) from northern domestic Chinese breeds (clustering with European sequences). This region constitutes a signature of interspecies admixture that contributed to the latitude adaptation of the two groups of Chinese domestic breeds.39 Ancient polymorphic numts we reported in our study further support the possibility that interspecies gene flow has contributed to shape the S.scrofa genome. Actually, an interesting advantage that numts can provide is derived by their sequence information that contains their approximate age of integration in the nuclear genome. Other numt regions should be tested to obtain a more complete picture of polymorphisms originated during the different events (interspecies admixture or recent insertions) that shaped the modern domestic pig genome and contributed to the constitution of European breeds and lines through different waves of gene flux and introgression between Asian and European domestic populations and breeds.

Accession numbers

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Italian Pig Breeders Association (ANAS) for providing samples used for DNA analyses.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at DNARES online.

Funding

This work was supported by University of Bologna RFO funds and MiPAAF Innovagen project. O.I.H. was supported by OTKA 111964 and COST Action TD1101.

References

- 1. Kazazian H.H. 2004, Mobile elements: drivers of genome evolution. Science, 303, 1626–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lopez J. V, Yuhki N., Masuda R., Modi W., O’Brien S.J.. 1994, Numt, a recent transfer and tandem amplification of mitochondrial DNA to the nuclear genome of the domestic cat. J. Mol. Evol., 39, 174–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cracraft J., Feinstein J., Vaughn J., Helm-Bychowski K.. 1998, Sorting out tigers (Panthera tigris): mitochondrial sequences, nuclear inserts, systematics, and conservation genetics. Anim. Conserv., 1, 139–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hazkani-Covo E., Zeller R.M., Martin W.. 2010, Molecular poltergeists: mitochondrial DNA copies (numts) in sequenced nuclear genomes. PLoS Genet., 6, e1000834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anthony N.M., Clifford S.L., Bawe-Johnson M., et al. 2007, Distinguishing gorilla mitochondrial sequences from nuclear integrations and PCR recombinants: guidelines for their diagnosis in complex sequence databases. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol., 43, 553–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wallace D.C., Stugard C., Murdock D., Schurr T., Brown M.D.. 1997, Ancient mtDNA sequences in the human nuclear genome: a potential source of errors in identifying pathogenic mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 94, 14900–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bensasson D. 2001, Mitochondrial pseudogenes: evolution’s misplaced witnesses. Trends Ecol. Evol., 16, 314–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leister D. 2005, Origin, evolution and genetic effects of nuclear insertions of organelle DNA. Trends Genet., 21, 655–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ricchetti M., Fairhead C., Dujon B.. 1999, Mitochondrial DNA repairs double-strand breaks in yeast chromosomes. Nature, 402, 96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hazkani-Covo E., Graur D.. 2007, A comparative analysis of numt evolution in human and chimpanzee. Mol. Biol. Evol., 24, 13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pereira S.L., Baker A.J., Margulis L., et al. 2004, Low number of mitochondrial pseudogenes in the chicken (Gallus gallus) nuclear genome: implications for molecular inference of population history and phylogenetics. BMC Evol. Biol., 4, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nergadze S.G., Lupotto M., Pellanda P., Santagostino M., Vitelli V., Giulotto E.. 2010, Mitochondrial DNA insertions in the nuclear horse genome. Anim. Genet., 41(Suppl 2), 176–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Groenen M.A.M., Archibald A.L., Uenishi H., et al. 2012, Analyses of pig genomes provide insight into porcine demography and evolution. Nature, 491, 393–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frantz L.A.F., Schraiber J.G., Madsen O., et al. 2013, Genome sequencing reveals fine scale diversification and reticulation history during speciation in Sus. Genome Biol., 14, R107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Giuffra E., Kijas J.M., Amarger V., Carlborg O., Jeon J.T., Andersson L.. 2000, The origin of the domestic pig: independent domestication and subsequent introgression. Genetics, 154, 1785–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Larson G., Dobney K., Albarella U., et al. 2005, Worldwide phylogeography of wild boar reveals multiple centers of pig domestication. Science, 307, 1618–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bosse M., Megens H.-J., Frantz L.A.F., et al. 2014, Genomic analysis reveals selection for Asian genes in European pigs following human-mediated introgression. Nat. Commun., 5, 4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kiełbasa S.M., Wan R., Sato K., Horton P., Frith M.C.. 2011, Adaptive seeds tame genomic sequence comparison. Genome Res., 21, 487–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frith M. C., Hamada M., Horton P., et al. 2010, Parameters for accurate genome alignment. BMC Bioinformatics, 11, 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsuji J., Frith M. C., Tomii K., Horton P.. 2012, Mammalian NUMT insertion is non-random. Nucleic Acids Res., 40, 9073–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frantz L., Meijaard E., Gongora J., Haile J., Groenen M.A.M., Larson G.. 2016, The Evolution of Suidae. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci., 4, 61–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K.. 2016, MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol., 33, 1870–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dayama G., Emery S. B., Kidd J.M., Mills R.E.. 2014, The genomic landscape of polymorphic human nuclear mitochondrial insertions. Nucleic Acids Res., 42, 12640–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rothschild M.F., Anatoly R. eds. 2011, The Genetics of the Pig. Cambridge: CABI. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deininger P.L., Moran J.V, Batzer M.A., Kazazian H.H.. 2003, Mobile elements and mammalian genome evolution. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 13, 651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Okada N., Shimamura M., Yasue H., et al. 1997, Molecular evidence from retroposons that whales form a clade within even-toed ungulates. Nature, 388, 666–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shedlock A.M., Okada N.. 2000, SINE insertions: powerful tools for molecular systematics. Bioessays, 22, 148–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chessa B., Pereira F., Arnaud F., et al. 2009, Revealing the history of sheep domestication using retrovirus integrations. Science, 324, 532–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deiningera P.L., Batzer M.A.. 1999, Alu repeats and human disease. Mol. Genet. Metab., 67, 183–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maksakova I.A., Romanish M.T., Gagnier L., Dunn C.A., van de Lagemaat L.N., Mager D.L.. 2006, Retroviral elements and their hosts: insertional mutagenesis in the mouse germ line. PLoS Genet., 2, e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sironen A., Thomsen B., Andersson M., Ahola V., Vilkki J.. 2006, An intronic insertion in KPL2 results in aberrant splicing and causes the immotile short-tail sperm defect in the pig. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 103, 5006–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim K.I., Lee J.H., Li K., et al. 2002, Phylogenetic relationships of Asian and European pig breeds determined by mitochondrial DNA D-loop sequence polymorphism. Anim. Genet., 33, 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shi N.-N., Fan L., Yao Y.-G., Peng M.-S., Zhang Y.-P.. 2014, Mitochondrial genomes of domestic animals need scrutiny. Mol. Ecol., 23, 5393–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ponting C.P., Hardison R.C.. 2011, What fraction of the human genome is functional? Genome Res., 21, 1769–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Borensztajn K., Chafa O., Alhenc-Gelas M., et al. 2002, Characterization of two novel splice site mutations in human factor VII gene causing severe plasma factor VII deficiency and bleeding diathesis. Br. J. Haematol., 117, 168–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Turner C., Killoran C., Thomas N.S.T., et al. 2003, Human genetic disease caused by de novo mitochondrial-nuclear DNA transfer. Hum. Genet., 112, 303–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goldin E., Stahl S., Cooney A.M., et al. 2004, Transfer of a mitochondrial DNA fragment to MCOLN1 causes an inherited case of mucolipidosis IV. Hum. Mutat., 24, 460–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen J.-M., Chuzhanova N., Stenson P.D., Férec C., Cooper D.N.. 2005, Meta-analysis of gross insertions causing human genetic disease: novel mutational mechanisms and the role of replication slippage. Hum. Mutat., 25, 207–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ai H., Fang X., Yang B., et al. 2015, Adaptation and possible ancient interspecies introgression in pigs identified by whole-genome sequencing. Nat. Genet., 47, 217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.