Abstract

Background

Differences in the epidemiology of lung cancer between Asians and non-Hispanic Whites have brought to light the relative influences of genetic and environmental factors on lung cancer risk. We set out to describe the epidemiology of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) among Asians living in California, and to explore the effects of acculturation on lung cancer risk by comparing lung cancer rates between U.S.-born and foreign-born Asians.

Methods

Age-adjusted incidence rates of NSCLC were calculated for Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and South Asians in California between 1988 and 2003, using data from the California Cancer Registry. Incidence rates were calculated and stratified by sex and nativity. We analyzed population-based tobacco smoking prevalence data to determine whether differences in rates were associated with prevalence of tobacco smoking.

Results

Asians have overall lower incidence rates of NSCLC compared with Whites (29.8 and 57.7 per 100,000, respectively). South Asians have markedly low rates of NSCLC (12.0 per 100,000). Foreign-born Asian men and women have an approximately 35% higher rate of NSCLC than U.S.-born Asian men and women. The incidence pattern by nativity is consistent with the population prevalence of smoking among Asian men; however, among women, the prevalence of smoking is higher among U.S.-born, which is counter to their incidence patterns.

Conclusions

Foreign-born Asians have a higher rate of NSCLC than U.S.-born Asians, which may be due to environmental tobacco smoke or non-tobacco exposures among women. South Asians have a remarkably low rate of NSCLC that approaches Caucasian levels among the U.S.-born. More studies with individual-level survey data are needed to identify the specific environmental factors associated with differential lung cancer risk occurring with acculturation among Asians.

Keywords: Lung cancer, epidemiology, Asian, nativity, smoking, exposures

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death in the U.S. and worldwide.[1, 2] Other than tobacco exposure, factors associated with increased lung cancer risk, such as environmental exposures and genetic susceptibility, are not well understood.[3] Differences in the epidemiology of lung cancer among ethnic groups may shed light on possible genetic and environmental influences on lung cancer development. Studies in Asian populations in particular have drawn attention to possible links between lung cancer and environmental exposures, other than tobacco smoke.[4] Relative to other racial/ethnic groups, Asians in general have been reported to have a lower incidence rate of lung cancer[4, 5], a predisposition to adenocarcinoma and bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) [6, 7], and a high prevalence of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations[8]. It is unclear the extent to which genetic factors or environmental exposures account for differences in lung cancer rates among Asians and non-Hispanic whites. The identification of relevant environmental risk factors that explain the lower rates in Asian populations may be useful targets for primary prevention of lung cancer, particularly in non-smokers. Identification of lung cancer susceptibility genes may help to define high-risk groups for secondary prevention. A detailed examination of rates among detailed Asian subgroups by nativity will lend some clues to the relative contributions of genetic and environmental factors.

With a diverse catchment population encompassing all 4.1 million Asians, including large populations of Chinese, Filipino, South Asian (Asian-Indian and Pakistani), Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese, the California Cancer Registry (CCR) offers a unique population to study the effect of race/ethnicity on the epidemiology of lung cancer.[9] We set out to describe the epidemiology of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) among Asians living in California, and to explore the effects of acculturation on lung cancer risk by comparing NSCLC rates between U.S.-born and foreign-born Asians. Differences in lung cancer incidence between U.S.-born and foreign-born Asian populations may be explained by environmental exposures, while differences in lung cancer incidence between Asians and non-Hispanic Whites (hereafter referred to as Whites) that are maintained among both U.S.-born and foreign-born Asians may be explained by genetic factors. We hypothesized that both U.S.-born and foreign-born East Asians are at disproportionately high risk for adenocarcinoma and BAC compared with Whites. We also posited that the risk of NSCLC among U.S.-born and foreign-born Asians would closely mirror the prevalence of cigarette smoking in these groups.

Methods

Data were obtained on cases of non-small cell lung cancer in the CCR diagnosed between 1988 and 2003. Case reporting to the CCR is estimated to be 99% complete (http://www.ccrcal.org/questions.html#how%20complete%20is%20ccr%20data). NSCLC cases were identified using primary site and histology codes for large cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, BAC, and non-specified NSCLC, as previously described.[10] This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at the Northern California Cancer Center and at the University of California San Francisco. No human subjects were contacted for this study.

Race/ethnicity and country of birth were obtained routinely by the CCR from hospital medical records. Patients of Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Vietnamese, Korean, or South Asian descent were included; these six ethnic groups comprised 91% of all Asian patients in the CCR between 1988 and 2003. Of 14,569 Asians with NSCLC in this study, 4889 cases (34%) were Chinese, 4542 (31%) were Filipino, 2060 (14%) were Japanese, 1618 (11%) were Vietnamese, 1149 (11%) were Korean, and 311 (2%) were South Asian. By comparison, in 2000, the statewide distribution of these six Asian ethnic groups (which comprised 90% of the total Asian population in California) was 29% Chinese, 28% Filipino, 9% Japanese, 13% Vietnamese, 10% Korean, and 10% South Asian. At that time, 36% of all Asians in the U.S. resided in California.

There was information on country of birth in the CCR for 13,398 (92%) cases. For 1,170 cases (8%) with unknown country of birth, the first five digits of the social security number (SSN), which correlates with its year of issuance, and date of birth were used to impute nativity. We had previously found that, compared to self-reported nativity, the sensitivity and positive predictive value of imputing nativity based on SSN and age of issue exceeded 80%. Thus, cases who had received their SSN before age 19 was imputed as being U.S.-born, and those who had received their SSN on or after age 19 was imputed as foreign-born[11, 12].

Population estimates by sex, race/ethnicity,-nativity, and -five year age group were obtained from the 1990 and 2000 SF-3 Census files for the state of California and extra-censal estimates were produced by the Greater Bay Area Cancer Registry and the CCR. Population counts for the detailed Asian subgroups for the year 2000 were based on an average of the minimum (single race alone) and maximum (multiple race Asians) estimate for each subgroup. Using the 1990 and 2000 estimates as benchmarks, a linear interpolation and extrapolation method was used to estimate the 1988-1989 and 2001-2003 population data. Linear interpolation and extrapolation assumes a fixed amount of population growth each year. Detailed explanation of this methodology is available elsewhere[13]. To apply nativity to these estimates, we used the 5% public use microdata sample from the 1990 and 2000 Censuses [14]; this allowed us to estimate the percent foreign-born by Asian sub-group, sex, and 5 year age group for California. Using linear interpolation, we estimated the percent foreign-born for all intercensal years. Extrapolations beyond the most recent census year were fixed at their last known values. Application of these percentages to the population estimates yielded our estimates of the foreign-born and native-born population.

Incidence rates were age-standardized to the 2000 U.S. standard million population. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were used to compare incidence rates between two groups, such as foreign-born and U.S.-born. Incidence rates were examined by year of diagnosis, and an age-adjusted annual percentage change (APC) statistic was calculated to evaluate secular trends in incidence rates. Rates based on fewer than 15 cases or a population less than 25,000 persons were considered unstable and not reported. Statistics were calculated using SEER*STAT software (Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software (www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat) version 6.3.5).

Tobacco consumption data on individual cases are not available in cancer registry data. However, population prevalence data on cigarette smoking status among all Asians, Chinese, Filipinos, and Koreans in California were obtained from the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), using AskCHIS Pro (http://www.chis.ucla.edu), combining data from the 2001 and 2003 CHIS. Information on smoking status among South Asians was obtained from the California Department of Health Services Tobacco Use Survey[15]. Data were not available on the Japanese population through AskCHIS, and smoking estimates among Vietnamese were unstable and are not presented.

Results

The incidence rate of NSCLC for California Asians between 1998 and 2003 was approximately half that of Whites (Table 1). Among Asian subgroups, South Asians had the lowest (12.0 per 100,000 person-years), Vietnamese had the highest (39.2 per 100,000 person-years), and Japanese and Koreans had intermediate rates of NSCLC. The incidence rates of histologic subtypes of NSCLC among Asian subgroups followed similar patterns to the rates of all NSCLC. Six percent of NSCLC cases among Asians were BAC compared to 4% among Whites (p<0.0001), however the incidence rate of BAC was slightly higher in Whites (2.3 compared with 1.7 per 100,000 person-years among Asians).

Table 1.

Age-adjusted annual incidence rates of NSCLC, California 1988-2003*

| All NSCLC | Adenocarcinoma | Squamous | BAC | Other NSCLC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites (n=177,181) | 57.7 | 20.7 | 14 | 2.3 | 20.7 |

| Male | 72.8 | 23.7 | 20.6 | 2.2 | 26.3 |

| Female | 46.7 | 18.5 | 8.9 | 2.4 | 16.8 |

|

| |||||

| All Asians (n=14,569) | 29.8 | 12.1 | 6 | 1.7 | 10.1 |

| Male | 42.4 | 14.9 | 10.8 | 1.7 | 15.1 |

| Female | 20 | 9.8 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 6.2 |

|

| |||||

| Chinese (n=4889) | 31.8 | 13.1 | 5.3 | 2 | 11.4 |

| Male | 41.4 | 14.9 | 9.1 | 1.7 | 16 |

| Female | 23.9 | 11.9 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 7.8 |

|

| |||||

| Filipino (n=4542) | 32 | 13.1 | 6.9 | 1.7 | 10.3 |

| Male | 51.2 | 18.2 | 13.9 | 2 | 17.1 |

| Female | 17.8 | 9.5 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 5.1 |

|

| |||||

| Japanese (n=2060) | 24.9 | 9.8 | 5.6 | 1.4 | 8.2 |

| Male | 34.9 | 12.3 | 9.3 | 1.1 | 12.1 |

| Female | 18.3 | 8.1 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 5.6 |

|

| |||||

| Korean (n=1149) | 26 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 1.2 | 8.6 |

| Male | 41.8 | 11.9 | 14.2 | 1.4 | 14.3 |

| Female | 16 | 6.8 | 3 | 1.1 | 5.2 |

|

| |||||

| Vietnamese (n=1618) | 39.2 | 17.1 | 7 | 2 | 13.1 |

| Male | 54.1 | 21.1 | 11.9 | 2 | 19 |

| Female | 26.5 | 13.6 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 8.2 |

|

| |||||

| South Asian (n=311) | 12 | 4.8 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 4 |

| Male | 14.9 | 4.5 | 3.9 | * | 5.7 |

| Female | 9.2 | 4.9 | 1.2 | * | 2.4 |

Rates are per 100,000 person-years, adjusted to 2000 U.S. Census population

Statistic not calculated, based on <15 cases

Age-adjusted incidence rates of NSCLC were higher among Asian men than women resulting in an IRR of 2.13 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.05-2.21); the IRR of white men relative to women was 1.56 (95% CI: 1.55-1.58). The IRRs comparing Asian men with women was 1.52 (95% CI: 1.45-1.60) for adenocarcinoma, 4.78 (95% CI 4.33-5.28) for squamous cell carcinoma, and 1.00 (95% CI 0.86-1.16) for BAC.

Incidence rates were stratified by nativity (Table 2a and 2b). Foreign-born Asians had a higher rate of NSCLC compared to U.S.-born Asians, with men 40% higher and women 34% higher overall (IRR 1.40, 95% CI: 1.31-1.50 among men; IRR 1.34, 95% CI 1.23-1.46 among women), with IRRs varying among the Asian subgroups. In contrast to most other groups, foreign-born South Asians were much less likely than U.S.-born South Asians to develop NSCLC. Foreign born Vietnamese also appeared to be less likely to develop NSCLC than their U.S.-born counterparts, although the estimate was unstable due to the relatively small number of U.S.-born Vietnamese. IRRs were also calculated for histologic subgroup of NSCLC, although analysis among U.S.-born Koreans, Vietnamese, and South Asians was limited by small numbers. Although rates were higher among men than women, as seen in Table 1, IRRs of NSCLC comparing foreign-born with U.S.-born Asians were similar between men and women (Tables 2a and 2b). Foreign-born men and women both had higher incidence rates of NSCLC and each of the histologic subgroups, compared with U.S.-born men and women. The same held true among Chinese and Japanese, the two largest ethnic subgroups studied.

Table 2a.

Incidence rates of Lung cancer among Asian-American men, stratified by nativity†

| All NSCLC | Adenocarcinoma | Squamous | BAC | Other NSCLC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Asians (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 45 (43.5-46.6) | 15.6 (14.7-16.5) | 11.6 (11.0-12.2) | 1.8 (1.6-2.0) | 16.0 (15.1-16.9) |

| U.S.-born | 32.1 (28.1-36.2) | 12.0 (9.6-14.5) | 7.8 (6.5-9.1) | 1.1 (0.7-1.5) | 11.2 (9.7-13.9) |

| IRR | 1.40 (1.31-1.50) | 1.30 (1.17-1.45) | 1.48 (1.31-1.70) | 1.63 (1.18-2.31) | 1.43 (1.28-1.61) |

|

| |||||

| Chinese (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 41.9 (40.1-43.7) | 14.4 (13.4-15.4) | 9.6 (8.8-10.5) | 1.7 (1.4-2.1) | 16.2 (15.1-17.4) |

| U.S.-born | 38.2 (33.5-43.2) | 16.1 (13.2-19.3) | 5.3 (3.8-7.2) | * | 15.2 (12.1-18.8) |

| IRR | 1.10 (0.96-1.26) | 0.89 (0.73-1.10) | 1.81 (1.32-2.57) | * | 1.06 (0.85-1.36) |

|

| |||||

| Filipino (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 52.3 (50.3-54.4) | 18.6 (17.4-19.9) | 14.2 (13.2-15.4) | 2.1 (1.7-2.5) | 17.4 (6.0-55.2) |

| U.S.-born | 31.1 (24.7-38.5) | 11.4 (7.9-15.9) | 6.2 (3.6-9.7) | * | 11.7 (7.6-16.8) |

| IRR | 1.68 (1.36-2.13) | 1.63 (1.17-2.38) | 2.31 (1.46-3.96) | * | 1.49 (1.03-2.30) |

|

| |||||

| Japanese (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 62.2 (54.2-71.1) | 20.4 (15.9-25.5) | 17 (12.7-22.0) | * | 22.0 (17.4-27.4) |

| U.S.-born | 31.1 (28.1-32.8) | 11.2 (9.8-12.7) | 8.4 (7.2-9.6) | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | 10.0 (8.7-11.5) |

| IRR | 2.05 (1.75-2.39) | 1.82 (1.38-2.37) | 2.03 (1.47-2.75) | * | 2.19 (1.67-2.85) |

|

| |||||

| Korean (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 42.5 (13.4-65.5) | 12.4 (10.5-14.5) | 14.8 (12.7-17.2) | 1.3 (0.8-2.2) | 14.0 (11.7-16.4) |

| U.S.-born | 33.7 (38.8-46.5) | * | * | * | * |

| IRR | 1.26 (0.64-3.19) | * | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| Vietnamese (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 54 (50.0-58.3) | 21.3 (18.9-24.0) | 11.8 (10.0-13.8) | 2.0 (1.4-2.9) | 18.9 (16.5-21.6) |

| U.S.-born | 75.4 (40.8-123.9) | * | * | * | * |

| IRR | 0.72 (0.43-1.33) | * | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| South Asian (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 14.5 (11.9-17.5) | 4.2 (3.0-5.7) | 3.7 (2.5-5.3) | * | 5.8 (4.1-8.0) |

| U.S.-born | 35.2 (16.1-63.4) | * | * | * | * |

| IRR | 0.41 (0.22-0.93) | * | * | * | * |

Rates are per 100,000 person years, adjusted to 2000 U.S. Census population. IRR: incidence rate ratio comparing Foreign-born to U.S.-born

Statistic not calculated, based on <15 cases

Table 2b.

Incidence rates of Lung cancer among Asian-American women, stratified by nativity†

| All NSCLC | Adenocarcinoma | Squamous | BAC | Other NSCLC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Asians (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 20.9 (20.1-21.7) | 10.3 (9.6-11.0) | 2.3 (2.2-2.6) | 1.7 (1.4-2.0) | 6.5 (5.9-7.1) |

| U.S.-born | 15.6 (13.5-18.7) | 7.6 (6.3-8.9) | 1.9 (1.2-2.3) | 1.4 (0.8-2.1) | 4.8 (3.4-6.2) |

| IRR | 1.34 (1.23-1.46) | 1.36 (1.20-1.54) | 1.25 (0.98-1.63) | 1.23 (0.93-1.66) | 1.37 (1.17-1.61) |

|

| |||||

| Chinese (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 24.4 (23.2-25.6) | 12.1 (11.2-13.0) | 2.1 (1.8-2.6) | 2.2 (1.8-2.6) | 8.0 (7.3-8.7) |

| U.S.-born | 20.9 (18.1-24.1) | 10.4 (8.5-12.6) | 1.7 (1.0-2.8) | 2.0 (1.2-3.1) | 6.8 (5.2-8.7) |

| IRR | 1.16 (1.00-1.36) | 1.16 (0.95-1.45) | 1.26 (0.75-2.30) | 1.07 (0.67-1.83) | 1.17 (0.89-1.56) |

|

| |||||

| Filipino (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 17.8 (16.8-18.9) | 9.5 (8.8-10.3) | 1.7 (0.7-3.6) | 1.6 (1.3-1.9) | 5.1 (4.5-5.7) |

| U.S.-born | 18.2 (13.1-24.3) | 9.0 (5.4-13.7) | * | * | 6.3 (3.4-10.2) |

| IRR | 0.98 (0.73-1.37) | 1.06 (0.69-1.80) | * | * | 0.81 (0.49-1.50) |

|

| |||||

| Japanese (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 26.4 (23.8-29.2) | 10.6 (9.0-21.4) | 5.3 (4.2-6.7) | 1.8 (1.2-2.6) | 8.7 (7.2-10.5) |

| U.S.-born | 13.3 (11.9-14.9) | 6.4 (9.0-12.4) | 1.7 (1.2-2.4) | 1.3 (0.9-1.8) | 3.9 (3.1-4.8) |

| IRR | 1.98 (1.69-2.32) | 1.65 (1.30-2.10) | 3.04 (2.04-4.62) | 1.43 (0.83-2.51) | 2.23 (1.67-2.99) |

|

| |||||

| Korean (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 16.2 (14.4-18.1) | 6.8 (5.7-8.1) | 3.1 (2.4-4.0) | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) | 5.1 (4.1-6.4) |

| U.S.-born | 16.9 (9.2-28.0) | * | * | * | * |

| IRR (95% CI) | 0.96 (0.57-1.78) | * | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| Vietnamese (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 26.7 (24.2-29.4) | 13.7 (12.0-15.6) | 2.7 (2.0-3.7) | 1.9 (1.3-2.7) | 8.4 (6.9-10.1) |

| U.S.-born | * | * | * | * | * |

| IRR | * | * | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| South Asian (95% CI) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 9.0 (6.9-11.5) | 4.9 (3.3-6.8) | * | * | 2.5 (1.5-3.9) |

| U.S.-born | 31.2 (15.9-54.2) | * | * | * | * |

| IRR | 0.29 (0.16-0.59) | * | * | * | * |

Rates are per 100,000 person years, adjusted to 2000 U.S. Census population. IRR: incidence rate ratio comparing Foreign-born to U.S.-born

Statistic not calculated, based on <15 cases

The annual percentage change (APC) in the incidence rate was calculated among U.S.-born and foreign-born Asian men and women between 1988 and 2003. The APC for U.S.-born Asian men was −9.9% (95% CI: −17.1, −2.1), reflecting an average of 10 percentage points decline per year in the incidence rate, whereas the APC for all other groups was small and not statistically significant (data not shown). This means that there was no significant change in NSCLC rates among women and foreign-born men.

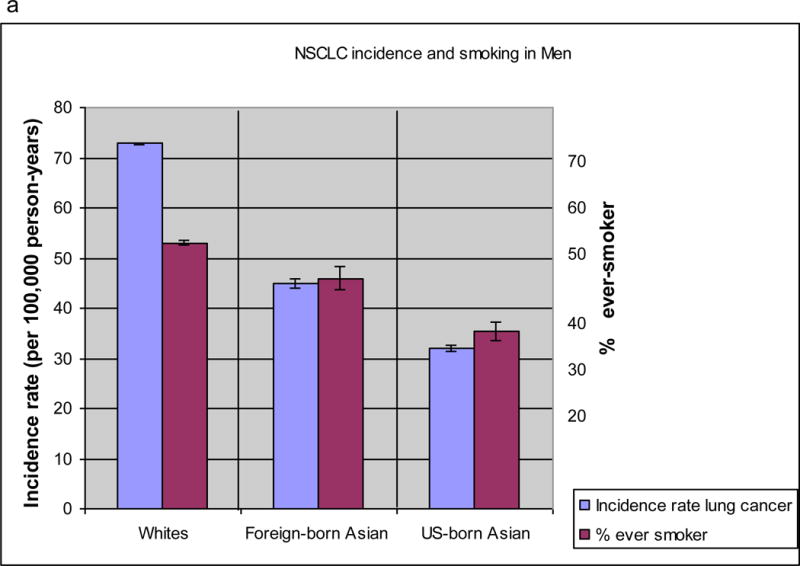

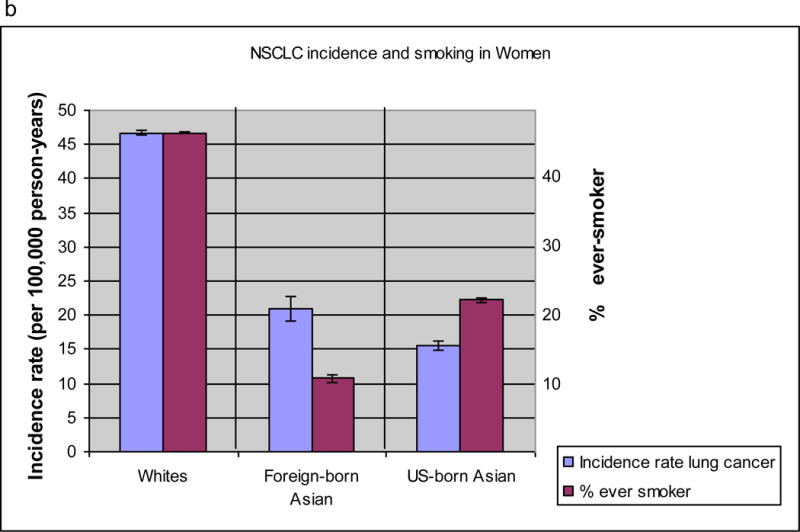

Differences in incidence rates of NSCLC were compared with differences in the prevalence of cigarette smoking across groups by race/ethnicity, nativity, and sex (Table 3). Figure 1 shows the proportion of ever-smokers plotted against NSCLC incidence rates within population subgroups. While rates of smoking vary considerably among Asian groups, in general, smoking is less common among U.S.-born Asian men compared with foreign-born Asian men consistent with the higher rates of NSCLC among foreign-born men. Although the opposite smoking pattern by nativity is true of Asian women, we find that NSCLC incidence rates are higher among foreign-born women, compared with U.S.-born women.

Table 3.

Smoking history of Asian-American adults, California

| Smoking status, Men (%) | Smoking status, Women (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | Former | Never | Ever | Current | Former | Never | Ever | |

| Whites | 19 | 34 | 47 | 53 | 16 | 28 | 56 | 44 |

| Asian | ||||||||

| U.S.-born | 17 | 19 | 65 | 35 | 11 | 11 | 78 | 22 |

| Foreign-born | 19 | 27 | 54 | 46 | 5 | 6 | 89 | 11 |

| Chinese | ||||||||

| U.S.-born | 9 | 14 | 77 | 24 | 9 | 7 | 84 | 16 |

| Foreign-born | 16 | 24 | 59 | 41 | 3 | 3 | 94 | 6 |

| Filipino | ||||||||

| U.S.-born | 25 | 9 | 66 | 34 | 13 | 11 | 76 | 24 |

| Foreign-born | 25 | 29 | 46 | 54 | 7 | 9 | 85 | 15 |

| Korean | ||||||||

| U.S.-born | 30 | 11 | 59 | 41 | 24 | 16 | 59 | 41 |

| Foreign-born | 38 | 33 | 29 | 71 | 8 | 7 | 85 | 15 |

| South Asian* | ||||||||

| U.S.-born | 9 | 11 | 80 | 20 | 5 | 4 | 91 | 9 |

| Foreign-born | 9 | 17 | 75 | 25 | 1 | 2 | 97 | 3 |

Source: California Health Interview Survey 2001 and 2003, all groups except South Asians

Source: California Asian Indian Tobacco Use Survey 2004.

Ever smoker defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes over lifetime

Figure 1.

Non-small cell lung cancer rates and percentage of ever-smokers among Whites, Foreign-born Asian, and U.S.-born Asian men (a) and women (b).

Discussion

In this study we have identified several surprising findings with implications for differences in lung cancer susceptibility or environmental exposures between Asians and whites living in California. While we did not have individual-level smoking data, our findings support further research into the genetic and environmental exposures that lead to the varying rates of NSCLC among the populations studied. Specifically, foreign-born Asian men and women together had a 35% higher rate of NSCLC on average than U.S.-born Asian men and women. There is substantial heterogeneity in the rates of NSCLC among the Asian subgroups, with South Asians having a strikingly low rate. Consistent with previous reports, we found that the rate of NSCLC among U.S. Asians is lower than that of Whites.[4, 5] For the most part, the rates of histologic subtypes of NSCLC were proportional to the overall rate of NSCLC in each subgroup analyzed. Of note, a larger proportion of Asians with NSCLC had BAC than Whites, a finding that appears to be consistent with the notion that BAC is more common among Asians.[7, 16] However, the incidence rate of BAC is actually higher in Whites. The IRR of BAC among foreign-born compared with U.S.-born Asians was similar to that for the other NSCLC subtypes studied.

Using population-based prevalence data from two California surveys, we found that foreign-born Asian men were more likely to smoke than their U.S.-born counterparts (46% vs 35%), whereas foreign-born Asian women were less likely to be smokers than U.S.-born Asians (11% vs 22%). Unfortunately, data on tobacco use among Japanese-Americans were not available for this study. A recent study describing the effects of acculturation on smoking among Asian-subgroups in California reported that, unlike other Asian subgroups, smoking rates among foreign-born Japanese women were higher compared with US-born Japanese women. This may in part explain why the effect of foreign-birth on lung cancer is highest among Japanese women.[17] With the exception of Japanese women, the inverse relationship between smoking and acculturation among Asian men and women has been reported elsewhere.[18] Yet foreign-born Asian women have substantially higher rates of NSCLC than U.S.-born women, suggesting that the increased rate of NSCLC among foreign-born Asian women is likely not completely attributable to personal history of cigarette smoking. Specifically, foreign-born Asian women have a higher rate of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, the two dominant histologies of NSCLC. While both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma are tobacco associated, squamous cell carcinoma is less common among never-smokers. These findings suggest that the increased rate of lung cancers among foreign-born Asian women may related to environmental tobacco exposure, given that smoking prevalence is higher among foreign-born Asian men compared with US-born Asian men. Other exposures that have been previously associated with a moderately increased risk of lung cancer among Chinese female non-smokers in Asia include cooking oil vapors, indoor coal burning, fungal infection, and tuberculosis.[3, 4] Investigation of the specific exposures responsible for the relatively high rates of lung cancer among U.S. Asian women, particularly notable given their low smoking rates, is needed.

Exposures other than tobacco smoke may also play a role in the low rate of lung cancer among South Asians. Although the prevalence of cigarette smoking in South Asians is about half that of other Asian subgroups, rates of NSCLC are still lower than those in subgroups with comparable cigarette smoking prevalences.[19] Meanwhile the incidence rate of NSCLC among U.S.-born South Asians men is more than double the rate among foreign-born South Asian men, while that among U.S.-born South Asian women is more than triple the rate seen among foreign-born South Asians women, despite similar tobacco exposure. There are several potential explanations for this finding. First, foreign-born South Asians are more likely to use Indian tobacco products such as gutka (chewable flavored tobacco), bidis (shredded tobacco wrapped in tendu leaves which are smoked), and snuff. These products may not increase the risk of lung cancer to the same degree as cigarettes do, and their use may also lead to the consumption of fewer Western cigarettes daily.[15, 20] Additionally, other environmental exposures such as dietary habits that are specific to South Asian cultures may be protective for lung cancer and warrant further study. Genetic factors that are protective against NSCLC are also possible, but seem less likely to play a protective role in this population given the much higher rate of NSCLC with acculturation. Epidemiologic studies with detailed individual-level exposure information may be useful to identify exposures associated with lung cancer risk modification among U.S.-born and foreign-born South Asians given the large difference in NSCLC rates seen with acculturation in this population.

Despite similar smoking prevalences, incidence rates of NSCLC are still lower among Asian men compared to White men; this finding is suggestive of differences in lung cancer susceptibility, racial/ethnic differences in tobacco metabolism, or differences in tobacco use among smokers. A recent study in the prospective, population-based Multiethnic Cohort revealed that Japanese-Americans had lower tobacco-adjusted incidence rates of lung cancer compared with Whites, suggesting that genetic and/or environmental factors are protective for lung cancer among Japanese.[21] Genetic polymorphisms and mutations modifying susceptibility to lung cancer may in part account for the lower incidence rate of lung cancer of Asians compared with Caucasians. Several investigators have reported increased odds of lung cancer among Asians with polymorphisms in genes responsible for enzymatic inactivation of carcinogens.[22–26] The relative importance of specific polymorphisms in lung cancer development and the prevalence and roles of these polymorphisms among the Asian ethnic groups is not known and deserves further study.

This is the largest study of the descriptive epidemiology of NSCLC in US Asians reported to date. However, certain limitations are worthy of mention. The CCR lacks information on smoking status among cancer cases, therefore we were unable to calculate NSCLC incidence rates directly stratified by or adjusted for smoking status. The lack of individual-level smoking data limits our conclusions of the relative effects of cigarette smoking relative to other exposures on NSCLC risk. Moreover, the prevalence of current or ever smoking may not accurately reflect the number of cigarettes smoked over a lifetime, which may vary among ethnic subgroups. [18]

Despite these limitations, population-based cancer surveillance data, used in conjunction with population risk factor survey data, is a powerful way to generate clues about cancer etiology. In this case, we found several notable patterns of lung cancer by nativity among U.S. Asian subgroups. The most interesting pattern is the paradoxical relationship between foreign birthplace (which was associated with a lower prevalence of cigarette smoking) and a higher rate of NSCLC among Asian women. Epplein and colleagues computed smoking-adjusted lung cancer incidence rates among Asians in two urban California SEER regions and the Seattle-Puget Sound region using smoking prevalence data for the state of California reported through a 1991-1992 California Department of Health Services survey on tobacco use [27]. Similar to our correlational analyses, their analysis showed a large discrepancy between smoking prevalence and lung cancer rates among Chinese females; we were able to show that this relationship was particularly notable among foreign-born Asian women.

This study is the first to our knowledge to incorporate nativity information in the population-based analysis of the descriptive epidemiology of lung cancer among Asians. This analysis was made possible through use of the CCR data, for which there are relatively large numbers of Asians, and relatively complete birthplace data. Since prior research suggests that registry birthplace incompleteness is not random[28], we used a novel imputation method based on SSNs to fill-in nativity for patients missing the information. Although based on the largest numbers of lung cancer cases available in any published work to-date, our study was still limited by small numbers of cases among less populous Asian-subgroups. Specifically, there were relatively few U.S.-born Korean, Vietnamese, and South Asians with lung cancer, resulting in unstable estimates of incidence rates in subgroups defined by sex-nativity and histologic subtype. While larger population-based registries such as the 18 combined Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries contain more Asian lung cancer patients than the CCR alone, information on nativity is absent in approximately 28% of Asians in SEER, and SSNs are not readily available for imputation. Furthermore, most other registries lack intra- and extra-censal population estimates by Asian subgroup, sex, and nativity, precluding estimation of rates and examination of trends, stratified by these characteristics.

In conclusion, Asians living in the U.S. are a diverse population with different environmental exposures that may in turn be responsible for differences in NSCLC incidence rates. More studies with individual-level survey data are needed to identify the specific environmental agents associated with differential lung cancer risk occurring with acculturation among Asians, especially among Chinese women and South Asians. Identification of such risk factors may lead to more successful primary prevention of lung cancer. Moreover, additional studies of lung cancer in a diverse populations including bio-specimen collection are crucial to understanding the interactions between genetic susceptibility, environmental exposures, and tumor genetics on lung cancer development, treatment, and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tim Miller, Ph.D. The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Health Services as part of the statewide cancer-reporting program mandated by the California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER Program) under contract N01-PC-35136 awarded to the Northern California Cancer Center, contract N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract N02-PC-15105 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program for Cancer Registries under agreement #U55/CCR921930-02 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors, and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Health Services, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their contractors and subcontractors is not intended, nor should be inferred.

Funding support reported in acknowledgments.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Cancer Facts and Figures 2007. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subramanian J, Govindan R. Lung cancer in never smokers: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:561–570. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam WK, White NW, Chan-Yeung MM. Lung cancer epidemiology and risk factors in Asia and Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:1045–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer rates and risks. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charloux A, Quoix E, Wolkove N, Small D, Pauli G, Kreisman H. The increasing incidence of lung adenocarcinoma: reality or artefact? A review of the epidemiology of lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:14–23. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zell JA, Ou SH, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H. Epidemiology of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: improvement in survival after release of the 1999 WHO classification of lung tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8396–8405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calvo E, Baselga J. Ethnic differences in response to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2158–2163. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeves T, Bennett C. We the people: Asians in the United States. U.S. Census Bureau; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Read WL, Page NC, Tierney RM, Piccirillo JF, Govindan R. The epidemiology of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma over the past two decades: analysis of the SEER database. Lung Cancer. 2004;45:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Block G, Matanoski GM, Seltser RS. A method for estimating year of birth using social security number. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;118:377–395. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu H, Ross RK, Bernstein L, Yatani R, Henderson BE, Mack TM. Cancers of the prostate and breast among Japanese and white immigrants in Los Angeles County. Br J Cancer. 1991;63:963–966. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cockburn M, Deapen D. Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance Program. Los Angeles, CA: University of South California; 2004. Cancer Incidence and Mortality in California: Trends by Race/Ethnicity, 1988-2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruggles S, Sobek M, Alexander T, Fitch CA, Goeken R, Hall PK, King M, Ronnander C. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center; 2004. In, Version 3.0 ed. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy W, Divan H, Shah D, Maxwell A, Freed B, Bastani R, Bernaards C, Surani Z. California Asian Indian Tobacco Use Survey - 2004. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raz DJ, Jablons DM. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma is not associated with younger age at diagnosis: an analysis of the SEER database. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:339–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.An N, Cochran SD, Mays VM, McCarthy WJ. Influence of American acculturation on cigarette smoking behaviors among Asian American subpopulations in California. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:579–587. doi: 10.1080/14622200801979126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SS, Ziedonis D, Chen KW. Tobacco use and dependence in Asian Americans: a review of the literature. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:169–184. doi: 10.1080/14622200601080323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakelee HA, Chang ET, Gomez SL, Keegan TH, Feskanich D, Clarke CA, Holmberg L, Yong LC, Kolonel LN, Gould MK, West DW. Lung cancer incidence in never smokers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:472–478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain RV, Mills PK, Parikh-Patel A. Cancer incidence in the south Asian population of California, 1988-2000. J Carcinog. 2005;4:21. doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haiman CA, Stram DO, Wilkens LR, Pike MC, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Le Marchand L. Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:333–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan-Yeung M, Tan-Un KC, Ip MS, Tsang KW, Ho SP, Ho JC, Chan H, Lam WK. Lung cancer susceptibility and polymorphisms of glutathione-S-transferase genes in Hong Kong. Lung Cancer. 2004;45:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho JC, Mak JC, Ho SP, Ip MS, Tsang KW, Lam WK, Chan-Yeung M. Manganese superoxide dismutase and catalase genetic polymorphisms, activity levels, and lung cancer risk in Chinese in Hong Kong. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:648–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng DP, Tan KW, Zhao B, Seow A. CYP1A1 polymorphisms and risk of lung cancer in non-smoking Chinese women: influence of environmental tobacco smoke exposure and GSTM1/T1 genetic variation. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:399–405. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-5476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raimondi S, Boffetta P, Anttila S, Brockmoller J, Butkiewicz D, Cascorbi I, Clapper ML, Dragani TA, Garte S, Gsur A, Haidinger G, Hirvonen A, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Kalina I, Lan Q, Leoni VP, Le Marchand L, London SJ, Neri M, Povey AC, Rannug A, Reszka E, Ryberg D, Risch A, Romkes M, Ruano-Ravina A, Schoket B, Spinola M, Sugimura H, Wu X, Taioli E. Metabolic gene polymorphisms and lung cancer risk in non-smokers. An update of the GSEC study. Mutat Res. 2005;592:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raimondi S, Paracchini V, Autrup H, Barros-Dios JM, Benhamou S, Boffetta P, Cote ML, Dialyna IA, Dolzan V, Filiberti R, Garte S, Hirvonen A, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, Imyanitov EN, Kalina I, Kang D, Kiyohara C, Kohno T, Kremers P, Lan Q, London S, Povey AC, Rannug A, Reszka E, Risch A, Romkes M, Schneider J, Seow A, Shields PG, Sobti RC, Sorensen M, Spinola M, Spitz MR, Strange RC, Stucker I, Sugimura H, To-Figueras J, Tokudome S, Yang P, Yuan JM, Warholm M, Taioli E. Meta- and pooled analysis of GSTT1 and lung cancer: a HuGE-GSEC review. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:1027–1042. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epplein M, Schwartz SM, Potter JD, Weiss NS. Smoking-adjusted lung cancer incidence among Asian-Americans (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:1085–1090. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez SL, Glaser SL, Kelsey JL, Lee MM. Bias in completeness of birthplace data for Asian groups in a population-based cancer registry (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:243–253. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000024244.91775.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]