Abstract

Cancer stem cells (CSCs), with their self-renewal ability and multilineage differentiation potential, are a critical subpopulation of tumor cells that can drive tumor initiation, growth, and resistance to therapy. Like embryonic and adult stem cells, CSCs express markers that are not expressed in normal somatic cells and are thus thought to contribute towards a ‘stemness’ phenotype. This review summarizes the current knowledge of stemness-related markers in human cancers, with a particular focus on important transcription factors, protein surface markers and signaling pathways.

Introduction

Individual tumors consist of a mixed cell population that differ in function, morphology, and molecular signatures. These tumors reside in and interact with their microenvironment, which consists of a wide variety of cell types and cellular structures, such as immune cells, fibroblasts, blood vessels, and the extracellular matrix. Tumor cells themselves can be of multiple clonal populations, each having accumulated unique molecular alterations over the course of tumor development and growth. In addition, tumor cells that are similar at the genetic level may have distinct modes of epigenetic regulation, further increasing the functional heterogeneity.

It has been hypothesized that only a small subset of tumor cells are capable of initiating and sustaining tumor growth; they have been termed cancer stem cells (CSCs) [1]. To date, CSCs have been isolated from many organs and confirmed to have stem cell-like abilities such as self-renewal, multilineage differentiation, and expression of stemness-related markers [2, 3]; some of these features are even confirmed by single cell analysis [4]. These cells may also play a role in disease recurrence after treatment and remission. As such, targeting of CSCs is currently an active area of therapeutic development.

CSCs are classified by the expression of stemness-related markers, which have been identified in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and adult stem cells, the two main types of human stem cells. Here, we summarize current knowledge about molecular markers and pathways that are not only involved in normal stem cell maintenance and self-renewal, but also regulate the stemness of CSCs. Investigation of these features may help elucidate the mechanism of CSC-driven tumorigenesis and lead to novel approaches for CSC-targeted cancer therapies.

Stemness-Related Transcriptional Factors in Cancers

Yamanaka et al. [5] showed in 2006 that that pluripotent stem cells could be obtained from mouse embryonic fibroblasts by combined expression of four transcriptional factors (TFs) - now named the Yamanaka factors (Oct4, c-Myc, Sox2, and Klf4). Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells can now be derived from a wide range of somatic cells via the over-expression of a cocktail of TFs [6] or a combination of TF expression with chemical compounds [7, 8]. Moreover, somatic cells can now be directly reprogrammed into entirely different cell types [9] through the expression of lineage-specific sets of transcription factors. Yamanaka's seminal discovery has introduced the concept that the fate of adult somatic cells can be controlled through TF expression. From another perspective, expression of stem-cell specific TFs can provide a signature for characterizing cell type as well as indicating their functional role.

There are currently approximately 25 TFs that have been reported to be expressed in stem cells. Of them, OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, Nanog, and SALL4 comprise a core regulatory network for embryonic stem cell maintenance and self-renewal. These TFs are highly expressed in embryonic stem cells; in contrast, they are mainly silenced in normal somatic cells, except in small groups of adult stem cell populations. Increasing evidence has shown that embryonic specific TFs are abnormally expressed in human tumor samples [10, 11], suggesting the presence of cancer stem cells. Retrospective studies on patient cohorts have also associated TF expression with survival outcomes in specific tumor types, suggesting that TF expression levels may also be useful for assessing patient prognosis[12]. Thus, detecting the expression level of these TFs, for example by immunohistochemistry staining, can aid in tumor diagnosis, classification, and therapeutic strategies.

A summary of these CSC TFs is shown in Table 1. These TF markers are also classified by tissue type, shown in Table 2. A few examples are listed here:

Table 1. Stemness-Related Transcriptional Factor (TF) Markers in Cancer.

| Marker | Other names | Function in stem cell | Characteristics | Expressed in Tumor types | Poor prognosis for tumor types | Selected Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | Oct3/4 or POU5F1 | Stem cell self-renew and poluropotency maintenance | Oct family of POU transcription factor. | Leukemia, Brain, Lung, Bladder, Ovarian, Pancreas, Prostate, Renal, Seminoma, Testis |

|

[11-16] |

| SOX2 | Stem cell self-renew and poluropotency maintenance | POU family binder transcription factor | Brain, Breast, Lung, Liver, Prostate, Seminoma, Testis |

|

[11],[17-29] | |

| KLF4 | Stem cell self-renew and poluropotency maintenance | Zinc-finger transcription factor | Leukemia, Myeloma, Brain, Breast, Head and neck, Oral, Prostate, Testis |

|

[27],[30-34] | |

| C-MYC | Stem cell self-renewal | Transcription factor and an oncogene | Leukemia, Lymphoma, Myoloma, Brain, Breast, Colon, Head and Neck, Pancreas, Prostate, Renal, Salivary-gland, testis |

|

[11],[51-55] | |

| Nanog | Stem cell self-renew and poluropotency maintenance | Transcription factor | Brain, Breast, Prostate, colon, liver, Ovarian, |

|

[36-44] | |

| SALL4 | Stem cell self-renew and poluropotency maintenance Differentiation regulation | Zinc finger transcription factor and an oncogene | Leukemia, Breast, Liver, Colon, Ovarian, testis |

|

[47-50] |

Table 2. Stemness-Related Markers in Different Cancer Types.

| Leukemia | Bladder | Breast | Colon | Gastric | Glioma/Medulloblastoma | Head and Neck |

Liver | Lung | Melanoma | Myeloma | Osteosarcoma | Ovarian | Pancreatic | Prostate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALDH1A1 | ALDH1A1 | ALDH1A1 | ALDH1A1 | ALDH1A1 | ALDH1A1 | ALDH1A1 | ALDH1A1 | |||||||

| CD34 | CD47 | CD49f/Integrin alpha 6 | CD166 | CD49f/Integrin alpha 6 | CD45 | TNFRSF16 | CD27/TNFRSF7 | Endoglin/CD105 | CD24 | CD49f/Integrin alpha 6 | ||||

| CD38 | CD24 | CD24 | CD24 | CD38 | CD24 | CD24 | CD151 | |||||||

| CD44 | CD44 | CD44 | CD44 | CD44 | CD44 | CD44 | CD44 | CD44 | CD44 | CD44 | ||||

| CD133 | CD133 | CD133 | CD133 | CD133 | CD133 | CD133 | CD133 | CD133 | ||||||

| CD47 | CD90 | CD26 | CD15/Lewis X | CD15/Lewis X | CD13 | CD20/MS4A1 | CD166 | |||||||

| CD96 | CD29 | CD90/Thy1 | CD90/Thy1 | CD90/Thy1 | CD19 | TRA-1-60(R) | ||||||||

| CD117/c-kit | CD117/c-kit | CD117/c-kit | ||||||||||||

| CD123/IL-3 R alpha | CEACAM-6/CD66c | Aminopeptidase N/CD13 | CD166/ALCAM | CD138Syndecan-1 | ALCAM/CD166 | |||||||||

| Lgr5/GPR49 | Lgr5/GPR49 | Lgr5/GPR49 | ||||||||||||

| EpCAM/TROP1 | EpCAM/TROP1 | EpCAM/TROP1 | EpCAM/TROP1 | |||||||||||

| CXCR4 | CXCR4 | CXCR4 | ||||||||||||

| CXCR1/IL-8 RA | CX3CR1 | |||||||||||||

| BMI-1 | BMI-1 | BMI-1 | BMI-1 | BMI-1 | BMI-1 | |||||||||

| Nestin | Nestin | Nestin | Nestin | |||||||||||

| Musashi-1 | Musashi-1 | |||||||||||||

| c-Myc | c-Myc | c-Myc | c-Myc | c-Myc | c-Myc | |||||||||

| SOX2 | SOX2 | SOX2 | SOX2 | SOX2 | ||||||||||

| OCT4 | OCT4 | OCT4 | OCT4 | OCT4 | ||||||||||

| KLF4 | KLF4 | KLF4 | ||||||||||||

| Nanog | Nanog | Nanog | Nanog | Nanog | ||||||||||

| SALL4 | SALL4 | SALL4 | SALL4 | SALL4 | SALL4 | |||||||||

| TIM3 | Rex1 |

Oct4

OCT4 expression has been detected in human brain, lung, bladder, ovarian, prostate, renal, testicular tumors, and leukemia, [12] both by RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry. Furthermore, high expression of OCT4 has been associated with poor prognosis in bladder cancer [13, 14], prostate cancer [15], medulloblastoma [16], and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [17].

Sox2

SOX2 has been found in brain, breast, lung, liver, prostate, and testicular tumors [12, 18, 19]; and its expression has been correlated with poor prognosis in stage I lung adenocarcinoma [18], squamous cell carcinoma [20, 21], gastric carcinoma [22-24], small cell lung cancer [25-28], and ovarian carcinoma [29, 30].

Kfl4

KLF4 has been found to be expressed in brain, breast, head and neck, oral, prostate, and testis tumors, as well as in leukemia and myeloma [12]. Expression of KLF4 can also be as a prognostic predictor for colon cancer [31] and head neck squamous cell carcinoma [24, 32]. In addition, nuclear localization of KLF4 has been associated with the aggressive phenotype of early-stage of breast cancer [33], as well as worse prognosis in nasopharyngeal [34] and oral cancers [35].

Nanog

Nanog has been shown to be expressed in brain, breast, prostate, colon, liver and ovarian tumors [36]. High expression of Nanog promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [37], which is an important developmental process for cancer cells to obtain stem cell characteristics. Nanog has also been associated with poor prognosis in breast [38], colorectal [39, 40], gastric [41], lung [42, 43], ovarian [44] and liver cancers [45].

Sall4

SALL4 expression has been detected in breast, liver, colon, ovarian, and testis cancers, and leukemia [46, 47]. The expression of SALL4 has been studied as a poor prognosis marker in hepatocellular carcinoma [48, 49], gliomas [50], and myelodysplastic syndromes [51].

C-myc

C-myc is an important transcriptional factor both in stem cells and cancers. As one of the most studied oncogenes, overexpression of C-myc has been shown to cause tumorigenesis in mouse models. Up to 70% of human cancers exhibit c-myc overexpression, including brain, breast, colon, head and neck, pancreas, prostate, renal, salivary-gland, and testis tumors, as well as leukemia and lymphoma [12, 52, 53]. C-myc expression has also been correlated with poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma [54] and early carcinoma of uterine cervix [55, 56].

Stemness-Related Surface Markers in Cancers

Cell surface proteins provide a feasible way for isolating and studying different cell types by flow cytometry or magnetic sorting. In addition, they are amenable for specific targeting, which is useful for disease monitoring and therapeutic delivery. Similar to stemness-related transcription factors, many surface markers that are highly expressed in stem cells are also expressed in human cancers as TRA-1-60, SSEA-1, EpCam, ALDH1A1, Lgr5, CD13, CD19, CD20, CD24, CD26, CD27, CD34, CD38, CD44, CD45, CD47, CD49f, CD66c, CD90, CD166, TNFRSF16, CD105, CD133, CD117/c-kit, CD138, CD151 and CD166. Table 2 describes most of the stemness-related surface markers and the tumor types they have been found to be expressed in. Among them, CD44 and CD133 are the most widely-used markers in CSC research and are also therapeutic targets in cancers.

CD44 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that plays different roles in cell division, migration, adhesion, and signaling [57]. It is normally expressed in both fetal and adult hematopoietic stem cells; and upon binding to hyaluronic acid, its primary ligand, CD44 mediates cell-cell communication and signal transaction. CD44 is highly expressed in many types of cancers include bladder, breast, colon gastric, glioma, head and neck, osteosarcoma, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancers, as well as leukemia [58][59]. CD44 is being studied as a therapeutic target in metastasizing tumors such as breast and colon cancer [60, 61], and also in leukemia [62].

CD133 is another transmembrane glycoprotein, and specifically localizes to cellular protrusions. CD133 is reported to be expressed in hematopoietic stem cells, endothelial progenitor cells, glioblastoma, and neuronal and glial stem cells [63, 64], and it is involved in cell growth and development [65]. Almost all tumor types can be detected with CD133 expression; and CD133+ tumor cells show stem cell-specific characteristics such as self-renewal, differentiation, and tumor formation in NOD-SCID mouse model [66]. After injection into immune-compromised mice, CD133+ cells also show chemo- and radio-resistance [66]. Studies has been pursued to use CD133 as a potential therapeutic target in colon cancer [67], ovary cancers [68], and metastatic melanoma [69]. CD133 has also been used as a target for drug delivery [70].

There are a number of other CSC surface markers that appear to function in specific types of tumors. For examples, SSEA-1 has been shown to be expressed in human colonic adenocarcinoma and glioblastoma [71, 72]. Similarly, TRA-1-60 has been associated with prostate tumors [73]. Lgr5 has been shown to be expressed in head and neck, colon and gastric tumors [74, 75]. CD90 has been detected in high grade human glioma [76, 77], as well as liver [78] and lung tumors [79, 80]; while CD117 has been used as a CSC marker in leukemia [81, 82] and gastrointestinal stromal tumor [83], as well as oral squamous cell carcinomas [84, 85] and ovarian tumors[86, 87]. CD117 has been shown to be overexpressed in hepatocellular [88] and pancreatic carcinoma[89]. CD24 has been used in combination with CD44 in breast cancer cell lines to show that CD44+/CD24- cancer cells exhibit drug resistance and invasive properties [90-92]. Studies have also shown that CD24 can be used as an independent prognostic marker non-small cell lung cancer [93, 94] and ovarian cancer [95].

Other Important Stemness-Related Markers

There are a number of stemness-related markers that are neither TFs nor cell surface proteins, which include ALDH, Bmi-1, Nestin, Musashi-1, TIM-3 and CXCR. The ubiquitous family of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzymes catalyzes the irreversible oxidation of cellular aldehydes in the cytoplasm. High activity of ALDH enzymes have been found in ESCs, adult hematopoietic and neural stem cells, as well as CSCs. ALDH activity in CSCs has been attributed to ALDH1A1 expression, which can regulate stem cell self-protection, differentiation, and population expansion. ALDH has been reported to have prognostic significance in head and neck squamous cell [96] and esophageal squamous cell carcinomas [97]. It is also being pursued as a therapeutic target in ovarian [98, 99] and non-small cell lung cancers [100].

BMI1 is a protein required for hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal [101] and neural stem cells [102]. Drug-induced expression of BMI1 has been shown to enhance stem cell populations in head and neck cancer models [103]. BMI1 has been reported as a marker for poor prognosis in oligodendroglial tumors [104] and breast cancer [105, 106]. Nestin and Musashi-1 have been detected in neural stem cells [107], where they both play an important role in stem cell self-renewal and maintenance. Nestin expression has been shown in transformed cells of various human malignancies, correlating with the clinical course of some diseases [108]. Furthermore, co-expression of Nestin with other stem cell markers was described as a CSC phenotype [109]. Nestin was reported as a potential target for tumor angiogenesis [110, 111]. Musashi-1 signaling was also detected in hematopoietic stem cells and it is being investigated as a potential therapeutic target and diagnostic marker for lung cancer [112].

Chemokines are small peptide molecules secreted by cells that affect the movement of neighboring cells, thus mediating cellular homing and migration. They are crucial for normal physiological functions, and are found to be dysregulated in cancers. The chemokine CXCL12 (SDF-1) and its receptor CXCR4 regulate cellular chemotaxis, cell adhesion, survival, proliferation, and gene transcription through multiple divergent pathways. CXCL12/CXCR4 interactions were shown to play an important role in the migration of hematopoietic stem cells [113]. CXCR4 is overexpressed in more than twenty cancer types, with discovered roles in tumor growth, invasion, angiogenesis, metastasis, relapse, and therapeutic resistance [114]. CXCR4 antagonists have been shown to disrupt tumor–stromal cell interactions, sensitize cancer cells to cytotoxic drugs, and reduce tumor growth and metastasis. Therefore CXCR4 is considered as a target for therapeutic intervention of lung [115][116] and breast cancer [117, 118]. It has also been used for noninvasive monitoring of disease progression and therapeutic guidance [114].

Stemness-Related Pathways

Stem cell maintenance, self-renewal, and differentiation pathways are involved in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis. Cancers commonly display aberrant activities within these pathways, often in a cell-context dependent manner. Here we discuss current evidence for Hedgehog (HH), Notch, JAK/STAT, PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Wnt/β-catenin pathway regulation in CSCs.

Hedgehog (Hh) pathway

The Hedgehog (Hh) pathway is a major regulator in vertebrate embryonic development, playing critical roles in stem cell maintenance, cell differentiation, tissue polarity, and cell proliferation, as well as EMT [119]. Hedgehog ligands (Desert Hedgehog, Sonic Hedgehog and Indian Hedgehog) bind to Ptch, activating a cascade of downstream signals that lead to the activation and nuclear localization of TFs, consequently followed by expression of genes that are involved in survival, proliferation, and angiogenesis [120]. Hedgehog signaling has been widely implicated in CSC self-renewal and cell fate determination [120], and is considered a potential therapeutic target in breast cancer and pancreatic cancer [121-123],

Notch pathway

Notch signaling is a critical part of stem cell fate determination and angiogenesis. Notch signaling is predominantly involved in cell-cell communication between adjacent cells through transmembrane receptors and ligands. In human ESCs, Notch signaling governs cell-fate determination in the developing embryo and is required for undifferentiated ESCs to develop all three embryonic germ layers [124]. In CSCs, it controls tumor immunity and CSC population maintenance [125, 126]. Notch signaling is frequently dysregulated in cancers, providing a survival advantage for tumors. In certain tumor types, activation of Notch signaling aids CSCs in maintaining their population in tumors, inducing EMT, and acquiring chemoresistance [127] Notch signalling is potential target for cancers [128, 129].

JAK/STAT pathway

The JAK-STAT signaling pathway is important in cytokine-mediated immune responses and known to be involved in many biological processes such as proliferation, apoptosis, and migration, as well as the regulation of stem cells. Cancer cells also show frequent dysregulation of the JAK/STAT. Studies in Drosophila first implicated JAK-STAT signaling in the control of stem cell maintenance in the male germline stem cell microenvironment [130][131]. Tightly controlled JAK-STAT signaling is required for stem cell maintenance and self-renewal. Furthermore, JAK-STAT activity is essential for anchoring the stem cells in their respective niches by regulating different adhesion molecules.

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway

The phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathways are crucial to stem cell proliferation, metabolism and differentiation. This pathway is frequently improperly regulated in human cancers [132]. Over 70% of ovarian cancers have active PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, making it a therapeutic target in this cancer type [133, 134], it is also a therapeutic target for neuroblastoma [135], endometrial cancer [136], and acute myeloid leukemia [137].

Wnt/β-catenin pathway

Pathways induced by Wnt ligands are highly evolutionarily conserved. Given their strong conservation in phylogeny, it is not surprising that Wnt pathways also play key roles in regulating stem cell differentiation and pluripotency. Consistently in many tissue types, dysregulation of Wnt pathway has been strongly associated with expansion of stem and/progenitor cell lineages, as well as carcinogenesis [138]. Hence, therapies targeting Wnt pathway may lead to treatment options in hematological malignancies [139], liver cancer [140], and other type of tumors [141].

Conclusion

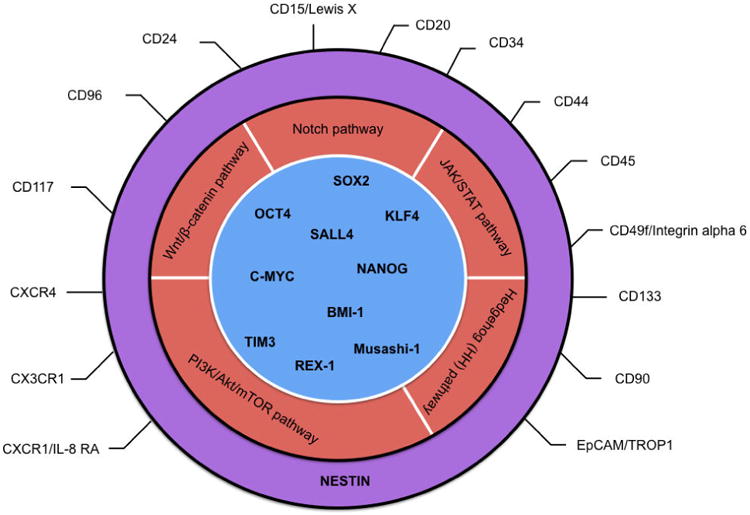

A primary goal in cancer research is to identify mechanisms driving drug resistance, and recent studies have implicated CSCs in intrinsic resistance models. Similar to normal stem cells, the abilities of self-renewal, maintenance, and differentiation of CSCs serve as a core reservoir for cancer initiation, development, and growth. The overexpression of stem cell specific TFs may contribute to the pathologic self-renewal characteristics of cancer stem cells while the surface molecules mediate interactions between cells and their microenvironment. Other stemness-related markers and pathways may promote cancer cell proliferation, progression, and metastasis. Our summary of stem cell markers by tissue types and cellular locations in Table 2 and Figure 1 highlights the complex nature of CSC regulation, which appears utilize different pathways in different cell or tissue types. This context-dependency makes it hard to find overarching CSC pathways and makers. Understanding the stemness-related features in cancers will not only provide important knowledge on molecular mechanisms for cancer pathogenesis, but also shed new light on development of effective therapeutic approaches specifically targeting these stemness-related features.

Figure 1.

Categories of cancer stem cell markers.

References

- 1.Pardal R, Clarke MF, Morrison SJ. Applying the principles of stem-cell biology to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(12):895–902. doi: 10.1038/nrc1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medema JP. Cancer stem cells: the challenges ahead. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(4):338–44. doi: 10.1038/ncb2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pattabiraman DR, Weinberg RA. Tackling the cancer stem cells - what challenges do they pose? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(7):497–512. doi: 10.1038/nrd4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel AP, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science. 2014;344(6190):1396–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1254257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radzisheuskaya A, Silva JC. Do all roads lead to Oct4? the emerging concepts of induced pluripotency. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(5):275–84. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu S, et al. Reprogramming of human primary somatic cells by OCT4 and chemical compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(6):651–5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen G, et al. Chemically defined conditions for human iPSC derivation and culture. Nat Methods. 2011;8(5):424–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelaini S, Cochrane A, Margariti A. Direct reprogramming of adult cells: avoiding the pluripotent state. Stem Cells Cloning. 2014;7:19–29. doi: 10.2147/SCCAA.S38006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monk M, Holding C. Human embryonic genes re-expressed in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2001;20(56):8085–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao W, et al. Embryonic stem cell markers. Molecules. 2012;17(6):6196–236. doi: 10.3390/molecules17066196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoenhals M, et al. Embryonic stem cell markers expression in cancers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;383(2):157–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu K, Zhu Z, Zeng F. Expression and significance of Oct4 in bladder cancer. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2007;27(6):675–7. doi: 10.1007/s11596-007-0614-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatefi N, et al. Evaluating the expression of oct4 as a prognostic tumor marker in bladder cancer. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2012;15(6):1154–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Resende MF, et al. Prognostication of OCT4 isoform expression in prostate cancer. Tumour Biol. 2013;34(5):2665–73. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0817-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodini CO, et al. Expression analysis of stem cell-related genes reveal OCT4 as a predictor of poor clinical outcome in medulloblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2012;106(1):71–9. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0647-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C, et al. OCT4 positively regulates Survivin expression to promote cancer cell proliferation and leads to poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillis AJ, et al. Expression and interdependencies of pluripotency factors LIN28, OCT3/4, NANOG and SOX2 in human testicular germ cells and tumours of the testis. Int J Androl. 2011;34(4 Pt 2):e160–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leis O, et al. Sox2 expression in breast tumours and activation in breast cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 2012;31(11):1354–65. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q, et al. Oct3/4 and Sox2 are significantly associated with an unfavorable clinical outcome in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(4):1233–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forghanifard MM, et al. Stemness state regulators SALL4 and SOX2 are involved in progression and invasiveness of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2014;31(4):922. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0922-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li XL, et al. Expression of the SRY-related HMG box protein SOX2 in human gastric carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2004;24(2):257–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, et al. SOX2 in gastric carcinoma, but not Hath1, is related to patients' clinicopathological features and prognosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(8):1220–6. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuoka J, et al. Role of the stemness factors sox2, oct3/4, and nanog in gastric carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2012;174(1):130–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.11.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, et al. Expression of Sox2 and Oct4 and their clinical significance in human non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(6):7663–75. doi: 10.3390/ijms13067663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, et al. The prognostic value of SOX2 expression in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue Y, et al. Clinicopathological and Survival Analysis of Japanese Patients with Resected Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring NKX2-1, SETDB1, MET, HER2, SOX2, FGFR1, or PIK3CA Gene Amplification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(11):1590–600. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sodja E, et al. The prognostic value of whole blood SOX2, NANOG and OCT4 mRNA expression in advanced small-cell lung cancer. Radiol Oncol. 2016;50(2):188–96. doi: 10.1515/raon-2015-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye F, et al. Expression of Sox2 in human ovarian epithelial carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137(1):131–7. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0867-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pham DL, et al. SOX2 expression and prognostic significance in ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013;32(4):358–67. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31826a642b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel NV, et al. Expression of the tumor suppressor Kruppel-like factor 4 as a prognostic predictor for colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(10):2631–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tai SK, et al. Persistent Kruppel-like factor 4 expression predicts progression and poor prognosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(4):895–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandya AY, et al. Nuclear localization of KLF4 is associated with an aggressive phenotype in early-stage breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(8):2709–19. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Z, et al. Loss of cytoplasmic KLF4 expression is correlated with the progression and poor prognosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Histopathology. 2013;63(3):362–70. doi: 10.1111/his.12176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CJ, et al. Loss of nuclear expression of Kruppel-like factor 4 is associated with poor prognosis in patients with oral cancer. Hum Pathol. 2012;43(7):1119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hart AH, et al. The pluripotency homeobox gene NANOG is expressed in human germ cell tumors. Cancer. 2005;104(10):2092–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mani SA, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133(4):704–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bareiss PM, et al. SOX2 expression associates with stem cell state in human ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73(17):5544–55. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng HM, et al. Over-expression of Nanog predicts tumor progression and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9(4):295–302. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.4.10666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu F, et al. Nanog: a potential biomarker for liver metastasis of colorectal cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(9):2340–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin T, Ding YQ, Li JM. Overexpression of Nanog protein is associated with poor prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma. Med Oncol. 2012;29(2):878–85. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-9860-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gialmanidis IP, et al. Expression of Bmi1, FoxF1, Nanog, and gamma-catenin in relation to hedgehog signaling pathway in human non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung. 2013;191(5):511–21. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9490-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li XQ, et al. Nuclear beta-catenin accumulation is associated with increased expression of Nanog protein and predicts poor prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Transl Med. 2013;11:114. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee M, et al. Prognostic impact of the cancer stem cell-related marker NANOG in ovarian serous carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22(9):1489–96. doi: 10.1097/IGJ.0b013e3182738307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun C, et al. NANOG promotes liver cancer cell invasion by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition through NODAL/SMAD3 signaling pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(6):1099–108. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Q, et al. Expression of SALL4 gene in patients with acute and chronic myeloid leukemia. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2013;21(2):315–9. doi: 10.7534/j.issn.1009-2137.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang F, et al. The next new target in leukemia: The embryonic stem cell gene SALL4. Mol Cell Oncol. 2014;1(4):e969169. doi: 10.4161/23723548.2014.969169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oikawa T, et al. Sal-like protein 4 (SALL4), a stem cell biomarker in liver cancers. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1469–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.26159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yong KJ, Chai L, Tenen DG. Oncofetal gene SALL4 in aggressive hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1171–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1308785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang L, et al. The expression of SALL4 in patients with gliomas: high level of SALL4 expression is correlated with poor outcome. J Neurooncol. 2015;121(2):261–8. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1646-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang F, et al. Stem cell factor SALL4, a potential prognostic marker for myelodysplastic syndromes. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6(1):73. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J, Orkin SH. Embryonic stem cell-specific signatures in cancer: insights into genomic regulatory networks and implications for medicine. Genome Med. 2011;3(11):75. doi: 10.1186/gm291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dang CV. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell. 2012;149(1):22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, et al. Prognostic significance of c-myc and AIB1 amplification in hepatocellular carcinoma. A broad survey using high-throughput tissue microarray. Cancer. 2002;95(11):2346–52. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riou G, et al. C-myc proto-oncogene expression and prognosis in early carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Lancet. 1987;1(8536):761–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92795-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colombo N, et al. Cervical cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(7):vii27–32. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Basakran NS. CD44 as a potential diagnostic tumor marker. Saudi Med J. 2015;363:273–9. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.3.9622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joshua B, et al. Frequency of cells expressing CD44, a head and neck cancer stem cell marker: correlation with tumor aggressiveness. Head Neck. 2012;34(1):42–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.21699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palapattu GS, et al. Selective expression of CD44, a putative prostate cancer stem cell marker, in neuroendocrine tumor cells of human prostate cancer. Prostate. 2009;69(7):787–98. doi: 10.1002/pros.20928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Orian-Rousseau V. CD44, a therapeutic target for metastasising tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(7):1271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arabi L, et al. Targeting CD44 expressing cancer cells with anti-CD44 monoclonal antibody improves cellular uptake and antitumor efficacy of liposomal doxorubicin. J Control Release. 2015;220(Pt A):275–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang S, et al. Targeting chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells with a humanized monoclonal antibody specific for CD44. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):6127–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221841110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Handgretinger R, et al. Biology and plasticity of CD133+ hematopoietic stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;996:141–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh SK, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63(18):5821–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Z. CD133: a stem cell biomarker and beyond. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2013;2(1):17. doi: 10.1186/2162-3619-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Singh SK, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432(7015):396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Catalano V, et al. CD133 as a target for colon cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;163:259–67. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.667404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Skubitz AP, et al. Targeting CD133 in an in vivo ovarian cancer model reduces ovarian cancer progression. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(3):579–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rappa G, Fodstad O, Lorico A. The stem cell-associated antigen CD133 (Prominin-1) is a molecular therapeutic target for metastatic melanoma. Stem Cells. 2008;26(12):3008–17. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith LM, et al. CD133/prominin-1 is a potential therapeutic target for antibody-drug conjugates in hepatocellular and gastric cancers. Br J Cancer. 2008;991:100–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mao XG, et al. Brain Tumor Stem-Like Cells Identified by Neural Stem Cell Marker CD15. Transl Oncol. 2009;2(4):247–57. doi: 10.1593/tlo.09136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin W, Modiano JF, Ito D. Stage-specific embryonic antigen (SSEA): determining the expression in canine glioblastoma, melanoma, and mammary cancer cells. J Vet Sci. 2016 doi: 10.4142/jvs.2017.18.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Giwercman A, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of embryonal marker TRA-1-60 in carcinoma in situ and germ cell tumors of the testis. Cancer. 1993;72(4):1308–14. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930815)72:4<1308::aid-cncr2820720426>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barker N, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449(7165):1003–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Simon E, et al. The spatial distribution of LGR5+ cells correlates with gastric cancer progression. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.He J, et al. CD90 is identified as a candidate marker for cancer stem cells in primary high-grade gliomas using tissue microarrays. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(6):M111 010744. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Parry PV, Engh JA. CD90 is identified as a marker for cancer stem cells in high-grade gliomas using tissue microarrays. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(4):N23–4. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000413227.80467.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang ZF, et al. Significance of CD90+ cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(2):153–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kawamura K, et al. CD90 is a diagnostic marker to differentiate between malignant pleural mesothelioma and lung carcinoma with immunohistochemistry. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;140(4):544–9. doi: 10.1309/AJCPM2Z4NGIIPBGE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yan X, et al. Identification of CD90 as a marker for lung cancer stem cells in A549 and H446 cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2013;30(6):2733–40. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Auewarakul CU, et al. C-kit receptor tyrosine kinase (CD117) expression and its positive predictive value for the diagnosis of Thai adult acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2006;85(2):108–12. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-0039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eren R, et al. T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with co-expression of CD56, CD34, CD117 and CD33: A case with poor prognosis. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;5(2):331–332. doi: 10.3892/mco.2016.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. CD117: a sensitive marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors that is more specific than CD34. Mod Pathol. 1998;11(8):728–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barth PJ, et al. CD34+ fibrocytes, alpha-smooth muscle antigen-positive myofibroblasts, and CD117 expression in the stroma of invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. Virchows Arch. 2004;444(3):231–4. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0965-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Margaritescu C, et al. The utility of CD44, CD117 and CD133 in identification of cancer stem cells (CSC) in oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC) Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52(3 Suppl):985–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang S, et al. Identification and characterization of ovarian cancer-initiating cells from primary human tumors. Cancer Res. 2008;68(11):4311–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Luo L, et al. Ovarian cancer cells with the CD117 phenotype are highly tumorigenic and are related to chemotherapy outcome. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011;91(2):596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Becker G, et al. CD117 (c-kit) expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2007;19(3):204–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Potti A, et al. HER-2/neu and CD117 (C-kit) overexpression in hepatocellular and pancreatic carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2003;23(3B):2671–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sheridan C, et al. CD44+/CD24- breast cancer cells exhibit enhanced invasive properties: an early step necessary for metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(5):R59. doi: 10.1186/bcr1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Giatromanolaki A, et al. The CD44+/CD24- phenotype relates to ‘triple-negative’ state and unfavorable prognosis in breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2011;28(3):745–52. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Adamczyk A, et al. CD44/CD24 as potential prognostic markers in node-positive invasive ductal breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. J Mol Histol. 2014;45(1):35–45. doi: 10.1007/s10735-013-9523-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee HJ, et al. CD24, a novel cancer biomarker, predicting disease-free survival of non-small cell lung carcinomas: a retrospective study of prognostic factor analysis from the viewpoint of forthcoming (seventh) new TNM classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(5):649–57. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d5e554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Karimi-Busheri F, et al. CD24+/CD38- as new prognostic marker for non-small cell lung cancer. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2013;8(1):65. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-8-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kristiansen G, et al. CD24 is expressed in ovarian cancer and is a new independent prognostic marker of patient survival. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(4):1215–21. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64398-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Qian X, et al. Prognostic significance of ALDH1A1-positive cancer stem cells in patients with locally advanced, metastasized head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(7):1151–8. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1685-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang L, et al. ALDH1A1 defines invasive cancer stem-like cells and predicts poor prognosis in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27(5):775–83. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li H, et al. ALDH1A1 is a novel EZH2 target gene in epithelial ovarian cancer identified by genome-wide approaches. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5(3):484–91. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Condello S, et al. beta-Catenin-regulated ALDH1A1 is a target in ovarian cancer spheroids. Oncogene. 2015;34(18):2297–308. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu X, et al. Targeting ALDH1A1 by disulfiram/copper complex inhibits non-small cell lung cancer recurrence driven by ALDH-positive cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gong H, Zhang YC, Liu WL. Regulatory effects of Bmi-1 gene on self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells--review. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2006;14(2):413–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Molofsky AV, et al. Bmi-1 dependence distinguishes neural stem cell self-renewal from progenitor proliferation. Nature. 2003;425(6961):962–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nor C, et al. Cisplatin induces Bmi-1 and enhances the stem cell fraction in head and neck cancer. Neoplasia. 2014;16(2):137–46. doi: 10.1593/neo.131744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hayry V, et al. Stem cell protein BMI-1 is an independent marker for poor prognosis in oligodendroglial tumours. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008;34(5):555–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2008.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Arnes JB, Collett K, Akslen LA. Independent prognostic value of the basal-like phenotype of breast cancer and associations with EGFR and candidate stem cell marker BMI-1. Histopathology. 2008;52(3):370–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang Y, et al. Cancer stem cell marker Bmi-1 expression is associated with basal-like phenotype and poor survival in breast cancer. World J Surg. 2012;36(5):1189–94. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1514-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Strojnik T, et al. Neural stem cell markers, nestin and musashi proteins, in the progression of human glioma: correlation of nestin with prognosis of patient survival. Surg Neurol. 2007;68(2):133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.10.050. discussion 143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Neradil J, Veselska R. Nestin as a marker of cancer stem cells. Cancer Sci. 2015;106(7):803–11. doi: 10.1111/cas.12691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang H, et al. Oct4 is expressed in Nestin-positive cells as a marker for pancreatic endocrine progenitor. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;131(5):553–63. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0560-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yamahatsu K, et al. Nestin as a novel therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer via tumor angiogenesis. Int J Oncol. 2012;40(5):1345–57. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Matsuda Y, Hagio M, Ishiwata T. Nestin: a novel angiogenesis marker and possible target for tumor angiogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(1):42–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang XY, et al. Musashi1 as a potential therapeutic target and diagnostic marker for lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2013;4(5):739–50. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Liekens S, Schols D, Hatse S. CXCL12-CXCR4 axis in angiogenesis, metastasis and stem cell mobilization. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(35):3903–20. doi: 10.2174/138161210794455003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chatterjee S, Behnam Azad B, Nimmagadda S. The intricate role of CXCR4 in cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2014;124:31–82. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-411638-2.00002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Otsuka S, Bebb G. The CXCR4/SDF-1 chemokine receptor axis: a new target therapeutic for non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3(12):1379–83. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818dda9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang Z, et al. Oncogenic roles and drug target of CXCR4/CXCL12 axis in lung cancer and cancer stem cell. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(7):8515–28. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5016-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Epstein RJ. The CXCL12-CXCR4 chemotactic pathway as a target of adjuvant breast cancer therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(11):901–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gil M, et al. Targeting CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling with oncolytic virotherapy disrupts tumor vasculature and inhibits breast cancer metastases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(14):E1291–300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220580110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Varjosalo M, Taipale J. Hedgehog: functions and mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2008;22(18):2454–72. doi: 10.1101/gad.1693608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cochrane CR, et al. Hedgehog Signaling in the Maintenance of Cancer Stem Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2015;7(3):1554–85. doi: 10.3390/cancers7030851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Merchant AA, Matsui W. Targeting Hedgehog--a cancer stem cell pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(12):3130–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gould A, Missailidis S. Targeting the hedgehog pathway: the development of cyclopamine and the development of anti-cancer drugs targeting the hedgehog pathway. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2011;11(3):200–13. doi: 10.2174/138955711795049871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Takebe N, et al. Targeting Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12(8):445–64. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yu X, et al. Notch signaling activation in human embryonic stem cells is required for embryonic, but not trophoblastic, lineage commitment. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(5):461–71. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hassan KA, et al. Notch pathway activity identifies cells with cancer stem cell-like properties and correlates with worse survival in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(8):1972–80. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Abel EV, et al. The Notch pathway is important in maintaining the cancer stem cell population in pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Capaccione KM, Pine SR. The Notch signaling pathway as a mediator of tumor survival. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(7):1420–30. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hirose H, et al. Notch pathway as candidate therapeutic target in Her2/Neu/ErbB2 receptor-negative breast tumors. Oncol Rep. 2010;23(1):35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Yuan X, et al. Notch signaling: an emerging therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Cancer Lett. 2015;369(1):20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bausek N. JAK-STAT signaling in stem cells and their niches in Drosophila. JAKSTAT. 2013;2(3):e25686. doi: 10.4161/jkst.25686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Stine RR, Matunis EL. JAK-STAT signaling in stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;786:247–67. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6621-1_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Morgensztern D, McLeod HL. PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway as a target for cancer therapy. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16(8):797–803. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000173476.67239.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Li H, Zeng J, Shen K. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway as a therapeutic target for ovarian cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290(6):1067–78. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3377-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mabuchi S, et al. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway as a therapeutic target in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fulda S. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway as therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9(6):729–37. doi: 10.2174/156800909789271521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Slomovitz BM, Coleman RL. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway as a therapeutic target in endometrial cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(21):5856–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Dos Santos C, et al. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: a new therapeutic target in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Bull Cancer. 2006;93(5):445–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Valkenburg KC, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin Signaling in Normal and Cancer Stem Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2011;3(2):2050–79. doi: 10.3390/cancers3022050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ashihara E, Takada T, Maekawa T. Targeting the canonical Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in hematological malignancies. Cancer Sci. 2015;106(6):665–71. doi: 10.1111/cas.12655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Gedaly R, et al. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in liver cancer stem cells and hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines with FH535. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Yao H, Ashihara E, Maekawa T. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in human cancers. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15(7):873–87. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.577418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]