Abstract

While intimate partner violence (IPV) against women and violence against children (VAC) have emerged as distinct fields of research and programming, a growing number of studies demonstrate the extent to which these forms of violence overlap in the same households. However, existing knowledge of how and why such co-occurrence takes place is limited, particularly in the Global South. The current study aims to advance empirical and conceptual understanding of intersecting IPV and VAC within families in order to inform potential programming. We explore shared perceptions and experiences of IPV and VAC using qualitative data collected in December 2015 from adults and children in Kampala, Uganda (n = 106). We find that the patriarchal family structure creates an environment that normalizes many forms of violence, simultaneously infantilizing women and reinforcing their subordination (alongside children). Based on participant experiences, we identify four potential patterns that suggest how IPV and VAC not only co-occur, but more profoundly intersect within the family, triggering cycles of emotional and physical abuse: bystander trauma, negative role modeling, protection and further victimization, and displaced aggression. The discussion is situated within a feminist analysis, including careful consideration of maternal violence and an emphasis on the ways in which gender and power dynamics can coalesce and contribute to intra-family violence.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence, Child maltreatment, Maternal violence, Gender, Qualitative research, Case vignette, Uganda

1. Background

Both intimate partner violence (IPV) against women and violence against children (VAC) are human rights abuses with far reaching consequences for the health and wellbeing of women, children, their families and communities (Ki-moon 2006; Ellsberg et al., 2008; UNICEF, 2014). Global estimates indicate 30% of ever-partnered women have experienced physical and/or sexual IPV (García-Moreno and Pallitt, 2013) and data from 96 countries estimates that over half the world’s children (1 billion) experienced emotional, physical or sexual violence in the year prior to the survey (Hillis et al., 2016). Recognizing that both IPV and VAC are widespread and commonly co-occur in the same households (Guedes et al., 2016), understanding and addressing potential intersections is emerging as a critical area for research and programming. This paper explores violence in the family, more specifically the overlap between VAC carried out by male and female caregivers and male-perpetrated IPV, a type of violence against women (VAW) defined as “any behavior by an intimate partner or ex-partner that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviors” (WHO, 2016).

For the most part, the fields of VAW and VAC have evolved in “distinct yet parallel” trajectories with distinct theoretical foundations and little integration in research or practice (Bidarra et al., 2016; Maternowska, Shakel et al. under review). While the impact of children witnessing IPV has received comprehensive attention—with research demonstrating a range of adverse physical, mental, and behavioral outcomes (Bair-Merritt et al., 2006) including future violence perpetration and victimization (Fulu et al., 2017; Jewkes et al., 2002)—relatively few studies have assessed the prevalence, risk factors, or consequences of other forms of co-occurring IPV and VAC. In 1998, Appel and Holden conducted a meta-analysis of 31 studies and found a median co-occurrence rate of 40% among clinical populations in the United States; more recent studies (including several from low and middle income settings) have also found high rates of co-occurrence (Chan, 2011; Rada, 2014; Carlson, Namy et al. under review).

Appel and Holden (1998) further developed conceptual models of family violence, including single perpetration (father carries out violence against his partner and children); sequential perpetration (father perpetrates violence against his partner who subsequently abuses her children) and bidirectional violence (violence perpetrated by both adults and children). They explain the etiology of violence as the interplay between social learning (Bandura, 1973), contextual “stressors,” and a genetic orientation towards antisocial behavior. Notably, however, their work overlooks important considerations around gender and power inequities in the family.

1.1. Patriarchy as a cross cutting risk

For decades, women’s rights activists, researchers, and programmers have emphasized how patriarchal systems shape social expectations in both functional and ideological terms to maintain male superiority over women (Dobash, 1979) and this understanding has been affirmed in international declarations (e.g., Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women: UN, 1993). Feminist analysis underscores the numerous ways in which patriarchal gender norms and “hegemonic masculinities” (Connell 1987)—normative ideals that define and reinforce certain men’s dominance, privilege and power—serve to produce gender hierarchies and validate men’s use of violence against women. Accordingly, gender inequality is understood as a root cause of VAW that must be centrally addressed in prevention programming (Jewkes et al., 2002; Heise, 2011; Michau et al., 2014).

While there has been some analysis of the linkages between patriarchy and paternal violence focused on how violent norms of masculinity contribute to men’s use of VAC (Levtov, van der Gaag et al., 2015), feminist analysis of maternal violence is limited, perhaps owing to legitimate hesitations around further stigmatizing women (Rees et al., 2015). Some historical feminist advocacy and scholarship, however, locates both IPV and VAC in the context of women’s subordination, arguing that women’s use of violence against their children cannot be extracted from the dynamics of oppression inevitable for women living under patriarchal values and institutions (e.g., marriage; motherhood) (Gordon, 1986; Dougherty, 1993; Featherstone and Fawcett, 1994).

1.2. Rationale and aims

While the upsurge of interest in the intersections of IPV and VAC has generated meaningful contributions, critical gaps remain. Qualitative studies are needed to explore how different family members experience intersecting violence and how normative beliefs and interpersonal dynamics can fuel (and resist) violence in the family. Although child and adult perspectives on violence differ (Naker, 2007; Breen et al., 2015), children’s voices have been largely overlooked in research. In addition, existing evidence is skewed towards high-income settings (Guedes et al., 2016) where social and gender norms, overall burden of co-occurring IPV and VAC, and structural adversities differ from other contexts. Finally, as noted above, a feminist analysis of adult-perpetrated VAC is limited in the literature.

This paper seeks to address these gaps through a qualitative exploration of IPV and VAC in Kampala, Uganda focused on two questions: what are the shared and contrasting perceptions of IPV and VAC? And how do IPV and VAC commonly intersect within the same household? We ground our study within a feminist analysis, emphasizing the ways in which patriarchal power is constructed (and sustained) in the family: (1) patriarchy promotes a clear hierarchy, with men in a superior position to women and children; (2) childhood and gender norms reflect this structure, de-valuing women and children (as well as their expected roles and behaviors) while prioritizing men (and hegemonic masculinities); (3) within the patriarchal family, men’s power/dominance must be demonstrated and reinforced, legitimizing violence as a form of social control over “subordinate” family members. Similarly, maternal violence must be situated within the broader context of the patriarchal family (rather than understood as a specific incident or individual pathology), which systemically disempowers women in many domains of their lives while granting them relative power vis-à-vis their children.

1.3. Contexts of IPV and VAC in Uganda

Like many countries in the region, poverty and related challenges are widespread in Uganda. The country ranks163 out of 188 on the Human Development Index, and over 70 percent of the population is “multi-dimensionally poor” (UNDP, 2015). Patriarchal structures that concentrate individual, familial and institutional power in the hands of men are salient in the social-cultural landscape (Mirembe and Davies, 2001; Ssetuba, 2005), where common gender norms expect women to be subservient and primarily responsible for domestic duties (Kyegombe et al., 2014; Wyrod, 2008).

Rates of both IPV and VAC are high; nearly 56% of ever-married women report physical and/or sexual IPV in their lifetime (UBOS and ICF, 2012) and available studies suggest that between 74% and 98% of children experience physical, emotional, sexual violence, or neglect, with much of this violence carried out by caregivers (Devries et al., 2013). Attitudes justifying IPV in some situations are widely held among both women and men (Speizer, 2010; Abramsky et al., 2012), as is social acceptance of beating children as discipline (Naker, 2007; Saile et al., 2014).

Despite these statistics, at the legal and policy level Uganda has fairly robust mechanisms to address VAW compared to other countries in the region, including the Domestic Violence Act (2010) and the National Elimination of Gender Based Violence Policy (2016). With regards to VAC, the recent confirmation of the 2015 Children (Amendment) Act is a promising step, which criminalizes corporal punishment in schools and strengthens other aspects of child protection. To date, however, operationalization of all policies remains weak.

2. Methods

2.1. Research setting and participants

The research was carried out in a low-income, densely populated parish in Kampala city. While residents are primarily Luganda speaking, an influx of migrants from across Uganda creates diversity within the community. To maximize geographic coverage we purposively selected 4 of 7 villages (sites) within the parish. In each site we focused on one respondent group (e.g., Site 1 for girls, Site 2 for boys, etc.) as an ethical consideration to avoid recruiting multiple members from the same family (Watts et al., 1999). We worked with local leaders to identify potential participants who represented the diverse socio-cultural characteristics existing within the community and met the following specific criterion: currently living with an intimate partner and has at least one child under 18 (for adults); currently living in a household with female and male caregivers (for children); as well as age and sex specifications. All adults were 18 years of age or over, and children were between 10 and 15 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics.

| Participant group (N) | Age (mean) | Children <18 currently living at home (mean) | Education: Primary only or none (%) | Christian (%) | Muslim (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers (28) | 30.8 | 3.2 | 62% | 76% | 24% |

| Fathers (27) | 31.7 | 3.3 | 35% | 54% | 46% |

| Daughters (25) | 12.3 | 2.9 | e | 82% | 18% |

| Sons (26) | 12.1 | 1.8 | e | 92% | 8% |

2.2. Data collection

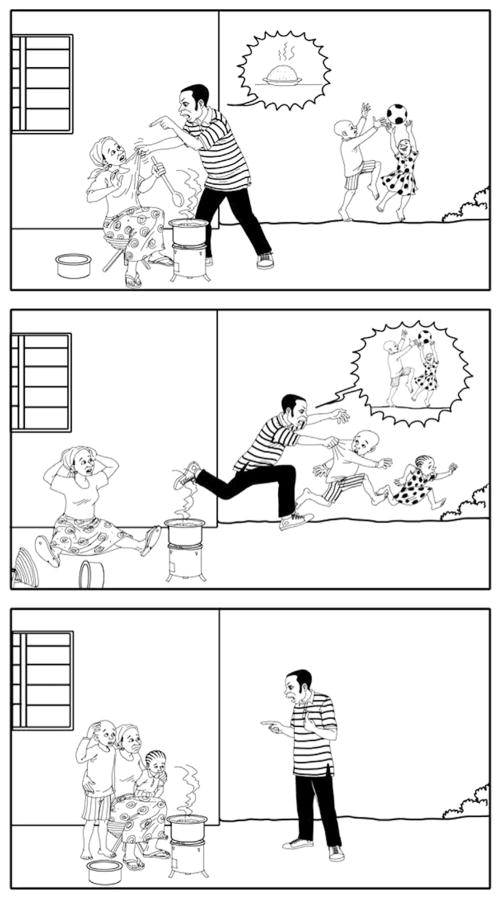

We conducted 16 FGDs (4 per respondent group) and 20 IDIs (5 per respondent group) in December 2015, engaging a total of 106 adults and children. Four Ugandan researchers with extensive experience in violence-specific research facilitated all the discussions in Luganda within a private setting (either in a school or community center). FGDs included an average of 5 participants and lasted between 2 and 2.5 h (including a break). FGDs were structured around case vignettes depicting intersecting IPV and VAC in the family (Fig. 1). Participants were asked to discuss the vignettes from the perspective of fictional characters and consider what led to the violence, likely consequences, and any suggestions for the family depicted. In addition, children’s FGDs included participatory techniques such as drawing and photo elicitation to redirect attention from (adult) facilitators and prompt more candid participation from children. IDIs lasted approximately 1 h; researchers used a semi-structured guide to discuss participants’ attitudes about the acceptability of violence in families and narrate personal accounts of violence they experienced, perpetrated or witnessed.

Fig. 1.

FGD Vignette-1 (Illustrator: Marco Tibasima).

The study was conducted in accordance with guidelines for the safe and ethical research on VAW (Watts et al., 1999) and VAC (Graham et al., 2013), and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ugandan National Council of Science and Technology (reference SS 3970).

2.3. Data preparation and analysis

All FDGs and IDIs were audio recorded (with prior consent) and fully transcribed and translated using a two-stage process. Transcriptions were spot checked by a research assistant and subsequently uploaded to Atlasti 7.5 (2016). We used a five-step framework analysis approach to analyze the data, including: familiarization, developing a thematic framework, indexing, charting, and mapping and interpretation (Ritchie and Spencer, 2002). We first familiarized ourselves with the data through reading, organizing and initial memoing that continued into indexing. We developed an a-priori codebook (based on pilot research) which was revised to accommodate emergent codes. Transcripts were coded line-by-line and simultaneously organized into frameworks corresponding with core research questions. During mapping and interpretation we summarized coded data on broader thematic levels, developing additional matrices and a conceptual model to describe key findings. While field notes from the participatory exercises were appended to the transcripts and reviewed during coding, these outputs were not systematically included in the current analysis.

We took several steps to increase the analytic rigor and credibility. First, our detailed memoing created an audit trail of all analysis decisions. Second, we held two analysis meetings with Luganda-speaking researchers to discuss In-vivo codes, cultural context and interpretation. Third, we convened a validation workshop with the local research team and experts in gender and violence prevention. Finally we triangulated data sources to deepen understandings of IPV, VAC, and intersecting violence in the study community (Padgett, 2008).

2.4. Findings

Our data confirm that co-occurrence of IPV and VAC is a common experience within participants’ families. Findings are presented under two broad themes: (1) perceptions of IPV and VAC, focusing on overlaps and disconnects; and (2) patterns of intersecting violence, based on experiences shared by participants.

2.5. Perceptions of violence

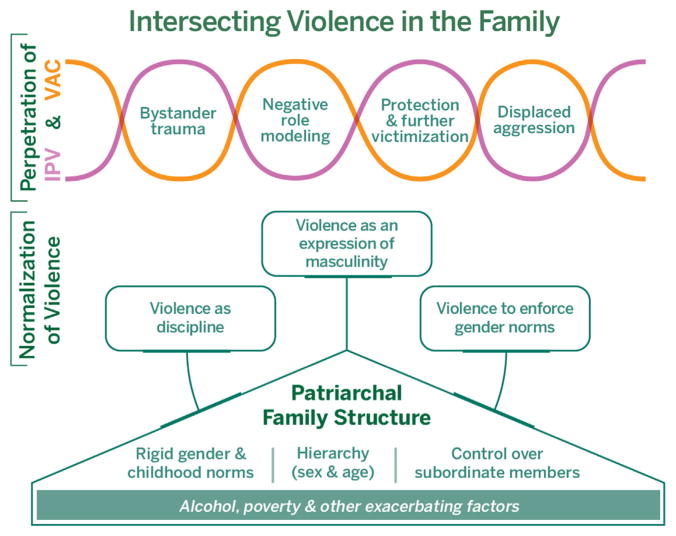

We found substantial overlap in how participants described and interpreted acts of IPV and VAC, reflecting strong acceptability of both forms of violence, often using similar language. As illustrated in the conceptual model (Fig. 2), adult and child participants frequently normalized violence: (1) as discipline; (2) a means to enforce gender norms; and (3) an expression of masculinity. Participants also recognized that poverty and alcohol could exacerbate these dynamics in ways that trigger (or escalate) intra-family violence, and, in some cases, defined limits to “acceptable” violence.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual Model.

Violence to discipline

The perpetration of VAC and IPV—specifically shouting and/or beating—was most frequently considered acceptable by participants as a response to a perceived deviation from socially prescribed roles and behaviors. The term “discipline” was pervasive in describing parents’ relationships with their children as well as the ideal roles expected of mothers and, to a lesser extent, fathers. As such, discipline was understood as a means to instill proper morals and behaviors in children, thus a critical attribute of good parenting:

[T]he most important thing parents can do to prove their love for their children is to raise them up with discipline and to prepare them to be able to sustain themselves in the future. (father-IDI)

While non-violent practices to discipline children were sometimes mentioned, overwhelmingly participants (including children) described the use of violent discipline (e.g., shouting, caning, or beating) and expressed a belief that violence is sometimes necessary:

[Discipline] is for their own good and it will enable them to have a bright future, because if they [parents] ignore a child and let him continue as a thief or drug addict … but if they beat you today and you realize the habits they don’t want … you drop the other habits and become a better person. (son-IDI)

Although “discipline” was rarely used to describe IPV in our data, a similar normative construct—tolerating (or expecting) violence to control or correct behavior— was implied. At times participants compared women experiencing abuse to “children,” explicitly infantilizing women:

Sometimes it is right [to shout at your wife], because there are times a wife behaves like a young child at home. If you are not tough with her she might fail to understand, there are things that she does and you feel that you have to shout at her to put a stop to it … you scare her a little bit … it is appropriate. (mother-IDI)

Violence to enforce gender norms

In nearly all cases, the specific justifications for IPV shared by participants reflected subordinate femininities, often referencing a woman’s failure to perform expected domestic roles. For example, when discussing hypothetical acts of IPV, mothers, fathers, daughters and sons all frequently characterized the woman as “big headed,” “behaving badly,” “going astray,” or “being rude”—thus “forcing” their husband’s aggression:

If the wife has done something wrong, it can force her husband to beat her. Like if she has not cooked food—he gave her money for food and she [spent] the money or maybe [she] came back late at night and found her husband already back home. (daughter-IDI)

Such patriarchal gender norms were also reflected in the adaptive responses suggested to avoid violence. Participants across sex and age groups recommended for the women vignette characters to “plead for forgiveness” or “keep quiet” in order to diffuse potential violence. Similar descriptions were offered in the case of children, for example a boy described how he would “kneel down and ask for forgiveness, much as I have done nothing” (son, IDI) to prevent being beaten.

Women strategized additional methods to deescalate (or prevent) IPV by embracing their subservient feminine roles or otherwise placating their husbands:

I [would] try to do away with all the things that can lead to my husband beating me or pointing at me. I start by checking myself … I [would] desist from doing the things that I used to do … I might have stopped making for him juice, but this time I make sure that by the time he comes home his juice is ready. If I haven’t been ironing his clothes, I try and iron his clothes. I start changing. (mother-FGD)

Men’s violence as an expression of masculinity

When violence was considered by participants as too extreme or not justified as an act of discipline, a separate normative framework emerged, rationalizing and often exonerating men’s use of violence (against a wife, a child, or both) in light of the pressures linked to fulfilling hegemonic masculine ideals. For example, a boy embellished Vignette-1 to better explain the father’s actions: “You told us that the father came back earlier than usual. I think he went to work and he was sacked without being paid … because of that he decided to revenge on his wife and children.” Another participant in the same FGD clarified: “… even if he has the money he can still do it [beat the wife and children] because in life we meet many challenges … he might have been beaten up by the thieves along the way and whenever he is hungry, he can recall all that and fight [with his family].”

Such assumptions—not included in the vignette itself—were common across sex and age groups, suggesting that male aggression is largely normalized (by men who use violence, as well as victims of this violence) as a manifestation of the anger or shame linked to failed masculinity. Some participants implied this behavior is “natural” or biologically determined:

There are some men who fight with their wives, because they are naturally like that, he always wants to fight and he wants to show his authority and power at home. He is so quarrelsome …that man is naturally quarrelsome and picks fights. (mother-FGD)

Both women and men shared nuanced understandings of how poverty and alcohol may interact with gender dynamics and exacerbate violence in the community. Women described how men’s frustration related to unemployment could be “transformed into violence” and a few men also reflected on violence as a deliberate strategy to navigate the chasm between their “responsibility” to provide and financial realities:

For example, the man will go out to look for money as a responsibility he has. But he may not get it [money] in return … If I left home under bad conditions and I go to work but I also fail to find a solution [money]. How do I handle that in a way that keeps the family intact? Because when you return without a solution, you have to resort to anger as a way to revert the attention. Because when you are angry no one will ask you for anything. Even the children who ask you to buy something will fear [you] and the wife will fear you as well. (father-FGD)

In other instances, participants described alcohol consumption and drunkenness as normal occurrences among men, fueling frustrations that could manifest as violence, even without “good reason:”

These are the type of men who go to the bars and take alcohol …so he comes home with all his frustration and booze and if he finds anything wrong at home – it could be that the food is not yet ready or the house is not yet cleaned. So he uses all his frustration and booze to beat the wife … there are so many who come home when they are drunk and they start beating people at home for no good reason. (mother-FGD)

Tensions and contradictions

While violence was widely tolerated among participants, our data reveal moments of contestation. Perhaps most pronounced were the personal accounts of distress and lasting harm after experiencing violence, which seem to contradict the many justifications shared by participants. In addition, respondents are careful to circumscribe the boundaries of “acceptable” violence; both adults and children offer caveats around severity, frequency, and enacting punishments proportional to the perceived transgression. In the case of children, the protocols were more defined, emphasizing where and how the child should be hit and the need for accompanying communication to explain the offense:

Sometimes, as a parent, you might decide to punish your child, but you must punish them in an appropriate way. If you have decided to cane the child, you should not overbeat, and if you have decided to beat the child, ask them to lie down and you beat him on the buttocks … you can give a child a few canes, like three of them. (mother-IDI)

Some participants did condemn the use of violence, though this position was more common in the case of IPV. Most notably, across sex and age groups perpetrating IPV in front of children was consistently rejected, even when participants justified the primary act of violence against the mother:

What he did is wrong, because he is beating his wife in the presence of her children. If he had disciplined her from the bedroom then he would have been right. (daughter-FGD)

When substantiating this position, both children and adults emphasized long-term consequences—that witnessing a husband’s aggression against his wife (and, in a few cases, reciprocal violence between both partners) could trigger boys to grow up into violent husbands or fathers:

Children are affected whenever you beat the mother in their presence, because these children will also treat their wives in the same way. We even have a saying that ‘It is the older birds that teach the young birds how to fly.’ Even this child will never respect his wife because he will always remember how his father treated his mother. (mother-FGD)

Some participants also considered how girls who witnessed IPV might become more vulnerable to violence as wives and even fearful about marriage:

[A]nd it is not good to fight in front of the children. Because they will get that same image and they will keep it in their mind. For example, I may decide never to marry in the future thinking the man is going to beat me. (daughter-FGD)

In a few cases, participants (mostly children) more fundamentally opposed IPV, arguing that women are “fellow adults” and “age mates,” implicitly contesting women’s positioning as children within the hierarchal family (and simultaneously reinforcing the acceptability of violence against children):

It is not right to beat your wife because she is a mature human being like you … she is not your daughter … I think it is just not good to beat your wife … because even if she had respect for you, she will gradually stop respecting you and in the end will even despise you. (son-IDI)

Though beating children was occasionally described as ineffective, an absolute rejection of VAC seldom emerged in our data (even among children), suggesting that social norms tolerating such violence are deeply entrenched. However children’s perspectives of violent discipline sometimes differed from parents, emphasizing the confusion, fear and pain associated with the experience.

I feel bad [remembering when my father beat me]. Because even up to now, I still feel the pain. The canes that I was beaten on that day—that was supposed to be a joyful day. That Christmas was not good for me, and I remember this event whenever it is time for Christmas. (son-IDI).

Conversely parents shared more pragmatic accounts, expressing that some beating and/or shouting are necessary parenting functions.

In a good relationship a parent is supposed to teach the child how to conduct themselves, even outside the home. Show them how to treat others including the elders and other people in society. The children only emulate whatever comes their way, that’s why sometimes when you ask them to do something and they refuse you use the stick to put them right, because simply talking to them will not help them realize whatever you mean. But the stick will prove that you are stressing the point. (father-IDI)

This widely shared belief that parental violence to discipline is, at times, concomitant with good parenting exposes perhaps the most visible disconnect that emerged betweenperceptions of IPV and VAC. While IPV was justified in many situations, a few participants did oppose this violence outright and no participant explicitly expressed that perpetrating IPV is necessary for being a “good” husband (though this perspective was at times implied). To the contrary, women’s relationship aspirations consistently revealed a desire for non-violent, emotionally connected and intimate partners:

[W]hen you come back home you should ask me about my day, you can give me a hug, show me that you love me …spare some time for me in the bedroom, put your love into action … I want you to declare that in the presence of all people …Once you do that for me, I will give you everything. Just show me that love. (mother-FGD)

2.6. Patterns of intersecting IPV-VAC

A second aim of this research was to explore specific examples that shed light on how families’ experience intersecting violence in their daily lives. Analysis of the disclosure data and hypothetical discussions suggest four potential patterns whereby IPV and VAC become intertwined in families where violence occurs (Fig. 2). These patterns are not mutually exclusive and largely (though not always) initiated by men’s use of violence against their partners and/or children.

Bystander trauma

The most common example of intersecting IPV-VAC occurred when one family member (most commonly a child, sometimes a mother) experienced trauma associated with witnessing their father (or husband) perpetrate violence against another family member. Several children emphasized their emotional distress after seeing their father perpetrate IPV, describing this experience as “sad” and “bad” as well as triggering “hatred” for their father, and wanting to “revenge against” him:

I would feel bad, we all feel bad seeing our mother is beaten or being mistreated in such a way … I would hate the situation and hate myself as well. (daughter-FGD)

Children and women also offered examples of how mothers suffer emotionally when witnessing their husbands beat their children, particularly when this violence was perceived as too extreme or otherwise unjustified:

When the father turned to the children, the mother cried so much … because here [earlier] she had endured the pain from his beating because she knew that the children were safe, but when he turned to the children she even put her hands on the head and wailed aloud … She was not crying because he had beaten her, but because he was beating her children … Most times we, the mothers, go through strong pain whenever something bad happens to our children. You imagine, even the chicken and the goats react whenever you touch their young ones. Now how about us women? (mother-FGD)

Negative role modeling

As noted above, participants consistently contested men’s use of IPV in front of children. While most often discussed hypothetically (in terms of future consequences), participants also linked children’s exposure to immediate impacts on mothers: diminished “respect” or “dignity” in the eyes of their children, which some associated with undermining women’s responsibilities as mothers. Such examples were shared by children and adults, however women most often articulated this potential loss of value and emotional connection:

[T]here is no way you can grab your wife and start beating her when your children are looking. You are not supposed to do it there, at least take her to the bedroom … talk about those issues from there and resolve them in the bedroom, without you despising her in the presence of her children. Because even her children will not respect her as their mother, they will also despise her. They will disrespect her, and even disobey her whenever she asks them to do something. (mother-FGD)

Even if the children are in the house [it is OK], as long as they do not get to understand what is going on. Because once the children hear your husband shouting at you, they will also start despising you. Like a child can even start telling you that, ‘I will report you to Daddy.’ Do you get that? That means that the child despises you, and thinks that you are a nobody who is always shouted at or beaten. (mother-IDI)

In a few cases, adults shared stories that described how their experiences of violence as children impacted them as a spouse and/ or parent. While men tended to highlight childhood experiences to justify their use of VAC (e.g., reflecting that their parent’s use of violent discipline was “effective” in moderating their own behaviors), a few women shared different perspectives. For instance, one woman who had experienced severe beating as a child rejected physical discipline as a mother, essentially breaking the intergen-erational cycle:

I never wanted to be beaten, yet I was over-beaten so much in my childhood, so I felt that pain and know that beating hurts. However, a time comes, you get used to the canes and no longer feel the pain … and you have this feeling that even if they beat me nothing will happen to me. Out of this experience, I personally learned that beating is not disciplining. (mother-IDI)

Protection and further victimization

Analysis of disclosure data uncovered several instances where a child (or mother) attempted to intervene against a violent husband/father resulting in further violence and illustrating another potential IPV-VAC intersection:

There is a seven year old child I saw in my neighborhood, when he saw his father beating his mother, he went inside the house, picked a bottle, he hit his father on the head. He felt bad seeing his father beating his mother. (mother-FGD)

Children mentioned these examples most frequently, describing both a general desire to protect their mothers and actual experiences of doing so: “In a situation like this I have to defend my mother by telling [my] father that it was my mistake and lie to him …. “ (son-FGD). The consequences of such actions were mixed; occasionally triggering violence against the child:

Sometimes their mother annoys you, you grab and hold her (in a way that causes pain) and when your child … notices she runs to hold you or the mother while at the same time crying, and because of anger you end up kicking that child as well. But it comes out of high anger. The children will always take their mother’s side because they spend more time together. Generally, it is because of anger that children also are affected by our fights. (father-FGD)

Other accounts, however, suggested more positive outcomes, such as one mother who believed their child’s intervention motivated her partner to reflect more deeply on his actions:

He [husband] grabbed me by the neck and started shaking me, my son stood up and told him that ‘Daddy do not beat Mummy.’ Up to now he still thinks about that incident. Whenever he is too angry, all of the sudden he bursts into laughter saying, ‘My son told me that I should never beat you’ - so things just stop there. (mother-IDI)

Displaced aggression

Personal experiences also exposed how intra-couple conflicts could lead to displaced aggression against children. Participants most frequently discussed such situations as an extension or redirection of the violence women experience from their partners, suggesting that a woman may transfer anger or stress to their children—at times also acknowledging a woman’s powerlessness vis-à-vis her husband (e.g., “because she cannot fight you”):

The reason children are beaten is because of the conditions at home. For example, the wife will tell you, ‘Here are your children. You don’t want to feed them’ … She will act out of anger, and because she cannot fight you, she will transfer the anger to the children and beat them. (father-FGD)

If I am the mother, at times I might have had misunderstandings with the father. By the time you [the child] come back home I am already angry over what the father has done to me … Because you are still angry … when they reach you, you just start beating. (mother-FGD)

Other narratives suggested a more protracted back-and-forth with the potential for either parent to manipulate or abuse their children in retaliation against the other. One woman described the guilt and trauma both she and her young step-son suffered when she forced him to leave home alone in the early morning to find his father, whom she presumed to be sleeping at his girlfriend’s home. A father explained displaced aggression in more general terms:

Whenever the husband is angered by the wife he ceases to be the father of their children, and will beat them for their mother’s actions. In the same way, whenever the mother is angered by the husband, the children become the father’s and she will beat them in revenge. For example whoever is angered by the other’s actions will refer to the children as the other’s bastards (father-FGD).

3. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study exploring community perceptions and experiences of intersecting IPV and VAC in sub-Saharan Africa. The analysis draws on perspectives of adults and children, perpetrators and survivors (categories that at times overlap) to deepen understanding of how and why IPV and VAC intersect within the family. We used participatory research techniques to meaningfully engage children, a valuable contribution given the gap in child-centered research methods to address violence (Breen et al., 2015) and the near-absence of children’s voices in IPV literature (Cater and Forssell, 2014).

Findings demonstrate that co-occurring violence is common in the study community, reflecting a constellation of intra-familial dynamics frequently resulting in poly-victimization (physical and emotional) of women and children. We identify common perceptions underlying both IPV against women and VAC: the normalization of violence to discipline and to enforce gender norms; and tolerance for men’s perpetration of violence as an expression of anger (or shame) associated with falling short of hegemonic masculine ideals. These findings support other research underscoring the persistence of men’s excepted role as providers and household heads despite the shifting socio-economic landscape in Kampala (Wyrod, 2008).

Participants shared various experiences of IPV and VAC and we identified four patterns that suggest how violence not only co-occurs in the family, but can more profoundly intersect and trigger cycles of abuse: (1) bystander trauma, where women and/or children suffer psychological abuse from witnessing violence against a family member; (2) negative role modeling, characterized by children learning that violence is a “normal” dynamic and mimicking abusive behavior in their current or future families (consistent with social learning theory, Bandura, 1973); (3) protection and further victimization, observed when interventions to protect a family member intensify anger and contribute to additional abuse; and (4) displaced aggression, expressed when parents engage their children to retaliate against one another, or when women’s own experience of IPV is redirected as violence against their children. Together these patterns illustrate how the consequences of violence extend beyond the incident itself, fundamentally affecting multiple family members and the trajectory of intra-familial relationships. This cycling of violence supports other work conceptualizing family violence as a process rather than an event (Bidarra et al., 2016).

While existing quantitative studies describe the scope of co-occurring IPV and VAC, the underlying patterns of intersecting violence remain poorly understood (Bidarra et al., 2016). Our analysis offers several overarching insights that may have relevance beyond the study community, articulated from a feminist perspective largely absent in the empirical literature on intersecting IPV-VAC. First, we illustrate how both IPV and VAC are frequently normalized by the patriarchal family structure that celebrates hegemonic masculinities (Connell, 1987) emphasizing power and control, infantilizes women and reinforces women’s subordination to men and children’s subordination to parents. As we describe, similar language is used to characterize the rationale for IPV and VAC, essentially blaming women and children for violating expected (submissive) identities/behaviors and, at the same time, validating violence as a legitimate form of social control. In circumstances where men’s use of violence is considered inappropriate (e.g., there exists no “good reason” for the violence), men may still be exonerated, as men’s violence is sometimes considered an uncontrollable (or “natural”) response to the stress associated with masculinity. Even the suggested coping strategies for women and children—prioritizing apology (in the absence of guilt)—reflect the extent to which they are expected to acquiesce to male (or generational) power and granted similar status within the family hierarchy. These critical linkages between gender inequality, the normalization of violence, and cycles of abuse within the family have been acknowledged in other recent research (Fulu et al., 2017).

Second, while we find substantial overlap between perceptions of IPV and VAC, we also observe some contradictions. Perhaps most notably, while both forms of violence are highly normalized, tolerance for VAC as a form of discipline was more conclusive, frequently considered a fundamental parenting function and largely accepted by parents and children themselves (despite at times acknowledging the emotional consequences). In contrast, a few participants exposed fault lines in the normative acceptability of IPV, emphasizing women’s status as autonomous adults and thus implicitly refuting their positioning “as children” in the family. This divergence perhaps reflects the differential power dynamics between couples—in which an aspiration for more equal power at times emerges—and between parents and children, where in any parent-child relationship, parents retain a legitimate role in guiding their children. Macro-level factors may also be at play; it is possible that social acceptability of VAW has lessened in response to the public discourse in Uganda around recent legislation and programming.

Third, participant experiences expose links between women’s gendered identities (as mothers and spouses) and intersecting violence in the family, a dimension that can be easily overlooked in research independently focused on either VAC or VAW. For instance, our data points to the psychological trauma a mother may feel when witnessing her partner’s use of violence against their children. We also find nuanced examples of how IPV affects the way women are perceived (and treated) by their children, triggering shame and potentially compromising their role as mothers. In such cases, women are concurrently victimized by their husband and children. When contesting the use of IPV in front of children, participants also recognize the intergenerational nature of violence, reflecting how the intersection between IPV and children’s exposure (a form of VAC) can reproduce patriarchy and perpetuate violence in future generations (substantiating trends documented in the quantitative literature, for example: Fulu et al., 2017, Jewkes et al., 2002).

Finally, the inclusion of women’s use of VAC in our findings provides an opportunity to contextualize maternal violence within a feminist understanding of power and family hierarchies. Most often in our data, women’s use of VAC was considered an acceptable way to control behavior (aligned with parenting roles that emphasize discipline as a normative and important function). We also found examples of displaced aggression, where mothers reacted violently towards their children after experiencing abuse from their husbands. As we argue in the introduction, such dynamics cannot be divorced from women’s systemic oppression and their relational power in the family. Thus within a highly constrained environment, women may violently express their powerlessness—or attempt to consolidate their own power—over children, who are perceived as subordinate within the hierarchy. While we acknowledge the risks in discussing women’s use of VAC, we accept that such sensitivities must be balanced against the value in understanding how women respond to (and resist) conditions of abuse (Dougherty, 1993; Rees et al., 2015). Towards this end, we hope to deepen understanding of how “terrains of power” (Hunnicutt, 2009) operate within the patriarchal family, at times creating conditions for maternal aggression as well as other coping strategies that can put children at risk.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. Although our guides did not intentionally restrict discussions to specific forms of violence, conversations naturally gravitated towards physical, emotional, and (at times) economic violence. As such, our findings do not include reference to child sexual abuse or marital rape, though existing data indicates both forms of violence are relatively common in Uganda (UBOS and ICF, 2012; ACPf, 2014). Relatedly, the vignette methodology inherently leads participants to consider certain scenarios, and may have limited the scope of discussion. For ethical reasons we did not speak with more than one member of the same household, and therefore were unable to verify disclosure stories, though interviewers were trained to probe extensively for both factual and emotional details. As with all qualitative research, findings may not be generalized beyond the study community.

3.1. Future research and programming

Further exploration of the dynamics within non-violent families could complement the current analysis, elucidating ways in which families defy existing norms and adopt more equitable relationships across sex and age. Similarly, an exploration of family resilience in stopping cycles of violence or realizing aspirations for non-violent relationships is needed. For instance, we found examples where reflecting on negative childhood experiences served as a motivation to reject violence, a dynamic that merits additional investigation. Finally while emerging evidence suggests that effectively reducing IPV can have positive impacts on children (Wathen and MacMillan, 2013; Kyegombe et al., 2015) further assessments of potential spillover effects on other family members when either IPV or VAC are reduced is another fruitful area for research.

For programming, findings reflect a contradiction between the many justifications for VAC and IPV, while rejecting children’s secondary exposure to violence precisely because it may lead to future perpetration. Reflecting on this disconnect may help bring to light the broader harms of any (direct and indirect) violence. More fundamentally, findings underscore the need to address the patriarchal family structure as a central approach to IPV/VAC prevention (in both integrated and independent approaches). The normative acceptance of men’s use of violence, rigid expectations around “appropriate” roles and behaviors, and persistence of victim-blaming attitudes emphasize that there is still much progress to be made in this area (in Uganda). Without this emphasis on transformational change, interventions risk being ineffective, or even reproducing gender and generational inequalities. Thus creating space to re-imagine the family and foster more equitable and intimate relationships between partners—often emphasized in IPV prevention—may also help reduce VAC and prevent cycles of violence in the family.

Acknowledgments

We are immensely grateful to all participants for sharing their experiences and thoughtful perspectives, to our team of research assistants (Angel Mirembe, Agnes Nabachwa, Devin Faris, Hassan Muluusi, Katherine Hall, Irene Nakhayenze, and Mary Dudzinsky), and to Jeanne Ward as well as our peer reviewers for their many insightful contributions. This research was supported by the Sexual Violence Research Initiative (grant no. 52065) hosted by the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the SAMRC.

References

- Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, Francisco L, Nakuti J, Musuya T, Kyegombe N, Starmann E, Kaye D, Michau L, Watts C. A community mobilisation intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV/AIDS risk in Kampala, Uganda (the SASA! Study): study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:96. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACPf. The African Report on Violence against Children. 2014 Retrieved from Addis Ababa. http://srsg.violenceagainstchildren.org/sites/default/files/documents/docs/african_report_on_violence_against_children_2014.pdf.

- Appel AE, Holden GW. The Co-Occurence of spouse and physical child abuse: a review and appraisal. J Fam Psychol. 1998;12(4):578–599. [Google Scholar]

- Computer Software. Scientific Software Development; Berlin: 2016. ATLAS-ti Version 7.5. [Google Scholar]

- Bair-Merritt MH, Blackstone M, Feudtner C. Physical health outcomes of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):e278–e290. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Aggression: a Social Learning Analysis. Prentice-Hall; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bidarra ZS, Lessard G, Dumont A. Co-occurrence of intimate partner violence and child sexual abuse: prevalence, risk factors and related issues. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;55:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen A, Daniels K, Tomlinson M. Children’s experiences of corporal punishment: a qualitative study in an urban township of South Africa. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;48:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson C, Namy S, Norcini Pala A, Wainberg M, Michau L, Nakuti J, Knight L, Allen E, Naker D, Devries K. Violence against Children and Intimate Partner Violence against Women in Uganda: Overlap and Common Contributing Factors. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-8115-0. (submitted for publication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cater A, Forssell AM. Descriptions of fathers’ care by children exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV) – relative neglect and children’s needs. Child Fam Soc Work. 2014;19(2):185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL. Children exposed to child maltreatment and intimate partner violence: a study of co-occurrence among Hong Kong Chinese families. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35(7):532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. Gender and Power : Society, the Person and Sexual Politics. Polity Press; Cambridge: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Allen E, Child JC, Walakira E, Parkes J, Elbourne D, Watts C, Naker D. The Good Schools Toolkit to prevent violence against children in Ugandan primary schools: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:232. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobash RE. In: Violence against Wives : a Case against the Patriarchy. Dobash R, editor. Free Press; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty J. Women’s violence against their children. Women Crim Justice. 1993;4(2):91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulu E, Miedema S, Roselli T, McCook S, Chan KL, Haardorfer R, Jewkes R. Pathways between childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, and harsh parenting: findings from the UN Multi-country Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(5):e512–e522. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone B, Fawcett B. Feminism and child abuse: opening up some possibilities? Crit. Soc Policy. 1994;14(42):61–80. [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno C, Pallitt C. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence. World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon L. Family violence, feminism, and social control. Fem Stud. 1986;12(3):453. [Google Scholar]

- Graham A, Powell M, Taylor N, Anderson D, Fitzgerald R. Ethical Research Involving Children. UNICEF; Florence: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guedes A, Bott S, Garcia-Moreno C, Colombini M. Bridging the gaps: a global review of intersections of violence against women and violence against children. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:31516. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.31516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise L. What Works to Prevent Partner Violence? An evidence overview (version 2.0) Department for International Development; London: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis S, Mercy J, Amobi A, Kress H. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: a systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):1–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunnicutt G. Varieties of patriarchy and violence against women: resurrecting” patriarchy” as a theoretical tool. Violence Against Women. 2009;15(5):553–573. doi: 10.1177/1077801208331246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Levin J, Penn-Kekana L. Risk factors for domestic violence: findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(9):1603–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ki-moon B. Report of the Secretary-general. United Nations Publication; 2006. Ending Violence against Women: from Words to Action. [Google Scholar]

- Kyegombe N, Abramsky T, Devries KM, Michau L, Nakuti J, Starmann E, Musuya T, Heise L, Watts C. What is the potential for interventions designed to prevent violence against women to reduce children’s exposure to violence? Findings from the SASA! study, Kampala, Uganda. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;50:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyegombe N, Abramsky T, Devries KM, Starmann E, Michau L, Nakuti J, Musuya T, Heise L, Watts C. The impact of SASA!, a community mobilization intervention, on reported HIV-related risk behaviours and relationship dynamics in Kampala, Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19232. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levtov R, van der Gaag N, Greene M, Kaufman M, Barker G. A MenCare Advocacy Publication. Washington, DC: Promundo, Rutgers, Save the Children, Sonke Gender Justice, and the MenEngage Alliance; 2015. State of the World’s fathers: child Rights Perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Maternowska C, Shakel R, Carlson C, Levtov R, Heise L. Unpacking the global politics of the age-gender divide in addressing violence (submitted for publication) [Google Scholar]

- Michau L, Horn J, Bank A, Dutt M, Zimmerman C. Prevention of violence against women and girls: lessons from practice. Lancet. 2014;385(9978):1672–1684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61797-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirembe R, Davies L. Is schooling a risk? Gender, power relations, and school culture in Uganda. Gend Educ. 2001;13(4):401–416. [Google Scholar]

- Naker D. From rhetoric to practice: bridging the gap between what we believe and what we do. Child Youth Environ. 2007;17(3):146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK. Qualitative Methods in Social Work Research. Vol. 36. Sage Publication; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rada C. Violence against women by male partners and against children within the family: prevalence, associated factors, and intergenerational transmission in Romania, a cross-sectional study. BMC Public health. 2014;14(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees S, Thorpe R, Tol W, Fonseca M, Silove D. Testing a cycle of family violence model in conflict-affected, low-income countries: a qualitative study from Timor-Leste. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. Qual Researcher’s Companion. 2002;573:305–329. [Google Scholar]

- Saile R, Ertl V, Neuner F, Catani C. Does war contribute to family violence against children? Findings from a two-generational multi-informant study in Northern Uganda. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(1):135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speizer IS. Intimate partner violence attitudes and experience among women and men in Uganda. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(7):1224–1241. doi: 10.1177/0886260509340550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssetuba I. Gender, Literature and Religion in Africa. Dakar: CODERISA; 2005. The Hold of Patriarchy: an Appraisal of Ganda Proverbs in Modern Gender Relations; pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- UBOS & ICF. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Uganda Bureau of Statistics and ICF International Inc; Kampala and Claverton: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women. 1993 Retrieved from. http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/48/a48r104.htm.

- UNDP. Work for Human Development Briefing Note for Countries on the 2015 Human Development Report Uganda. 2015 Retrieved from. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/UGA.pdf.

- UNICEF. Hidden in Plain Sight: a Statistical Analysis of Violence against Children. UNICEF; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: impacts and interventions. Paediatr Child Health. 2013;18(8):1205–7088. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C, Heise L, Ellsberg M, Moreno C. Putting Women’s Safety First: Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Research on Domestic Violence against Women. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Fact Sheet. Violence against Women: Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence against Women. 2016 Retrieved from. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs239/en/

- Wyrod R. Between Women’s rights and Men’s authority: masculinity and shifting discourses of gender difference in urban Uganda. Gend Soc. 2008;22(6):799–823. doi: 10.1177/0891243208325888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]