Abstract

Grapevine trunk diseases: Eutypa dieback, esca and Botryosphaeria dieback, which incidence has increased recently, are associated with several symptoms finally leading to the plant death. In the absence of efficient treatments, these diseases are a major problem for the viticulture; however, the factors involved in disease progression are not still fully identified. In order to get a better understanding of Botryosphaeria dieback development in grapevine, we have investigated different factors involved in Botryosphaeriaceae fungi aggressiveness. We first evaluated the activity of the wood-degrading enzymes of different isolates of Neofusicoccum parvum and Diplodia seriata, two major fungi associated with Botryosphaeria dieback. We further examinated the ability of these fungi to metabolize major grapevine phytoalexins: resveratrol and δ-viniferin. Our results demonstrate that Botryosphaeriaceae were characterized by differential wood decay enzymatic activities and have the capacity to rapidly degrade stilbenes. N. parvum is able to degrade parietal polysaccharides, whereas D. seriata has a better capacity to degrade lignin. Growth of both fungi exhibited a low sensitivity to resveratrol, whereas δ-viniferin has a fungistatic effect, especially on N. parvum Bourgogne S-116. We further show that Botryosphaeriaceae are able to metabolize rapidly resveratrol and δ-viniferin. The best stilbene metabolizing activity was measured for D. seriata. In conclusion, the different Botryosphaeriaceae isolates are characterized by a specific aggressiveness repertory. Wood and phenolic compound decay enzymatic activities could enable Botryosphaeriaceae to bypass chemical and physical barriers of the grapevine plant. The specific signature of Botryosphaeriaceae aggressiveness factors could explain the importance of fungi complexes in synergistic activity in order to fully colonize the host.

Introduction

Since 1974, European viticulture is facing a new class of severe diseases called grapevine trunk diseases. The major grapevine trunk diseases, i.e. esca, Eutypa dieback and Botryosphaeria dieback, caused by a complex of xylem-inhabiting fungi, are very harmful and therefore an important matter of concern for the viticulture. Indeed, grapevine trunk diseases generate severe yield reduction in vineyards (for review, see [1] and [2]), causing colossal losses which have been estimated to exceed 1 billion dollars per year [3]. Trunk diseases, which incidence has increased since currently no effective plant protection strategies are available, are associated with several symptoms, such as sectorial and/or central necrosis in woody tissues, brown stripes or cankers, leaf discoloration and withering of inflorescence and berries resulting in long-term death of the plant [4–6].

Grapevine trunk diseases involve different actors and factors whose understanding is not yet complete. Koch's postulates, designed to identify the link between diseases and causal agents, are difficult to demonstrate. Indeed, the reproduction of all symptoms, especially the foliar symptoms, by artificial inoculation is not always verified. In the present work, we focused on Botryosphaeria dieback, which is associated with a wide range of Botryosphaeriaceae species [7]. Typical symptoms found in vineyards are foliar discolorations that vary from red to white cultivars, wood discolorations, grey sectorial necrosis and orange/brown area just beneath the bark, leading to long-term plant death [4–7]. More than 30 different Botryosphaeriaceae species have been found in vineyards in several countries based on morphological traits and genetic markers [7–11]. Neofusicoccum parvum (teleomorph form: Botryosphaeria parva; [12,13] and Diplodia seriata De Not. (teleomorph form: Botryosphaeria obtusa (Schwein.) [14–16] have been especially associated with Botryosphaeria dieback [10,17]. Several authors demonstrated a great variability in the aggressiveness level between N. parvum and Diaporthe species [18]. In detail, toxicity assays on Vitis cells and leaves and study of necrosis development after artificial inoculation of Vitis canes, showed that N. parvum is more aggressive than D. seriata [7,9,19–23].

Aggressiveness of fungi associated with trunk diseases may be related to different fungal activities. Variation in wood-decay abilities and production of phytotoxic compounds are thought to be main factors contributing to trunk disease fungi unique disease symptoms. Mycelia of trunk disease fungi are detected in the trunk but never from the symptomatic leaves or berries of infected plant [24], then it has been hypothesized that toxins secreted by fungi in the trunk are translocated to the leaves and berries via the xylem sap to induce symptoms [25]. Indeed, several phytotoxic secondary metabolites are produced by the main fungi associated with trunk diseases (for review, see [26]). In the case of B. dieback fungi, dihydroisocoumarins are produced by D. seriata, whereas N. parvum is characterized by the synthesis of dihydrotoluquinones, epoxylactones, dihydroisocoumarins and hydroxybenzoic acids [23,27].

Concerning wood decay activity, different authors demonstrated that pathogens associated with esca or Eutypa dieback are able to produce wood degradation enzymes in order to gain nutrients and to progress in the trunk. Different authors discovered that wood decay enzymes such as xylanases, cellulases, β-glucanases, chitinases, proteases, oxydases, glucosidases and starch degrading enzymes are produced by Eutypa lata, responsible for Eutypa dieback [28–30]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that E. lata targets glucose-rich polymers and that after infection, glucose and xylose of the hemicellulose cell wall fraction were depleted both in susceptible (Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon) and tolerant (V. vinifera cv. Merlot) grapevine cultivars. Phaeomoniella chlamydospora and Phaeoacremonium minimum comb. nov. are two fungi responsible for the esca syndrome in grapevine [30]. It has been reported that P. minimum possessed enzyme activities responsible for the degradation of polysaccharides (xylanase, exo- and endo-β-1.4-glucanase and β-glucosidase), whereas no ligninase activity was measured [31]. In contrast, none of these enzyme activities was measured in P. chlamydospora, which was characterized by a pectinolytic activity enabling to circulate through the vessels without degrading the membrane [32,33]. These studies suggest that these two fungi have different strategies of wood colonization.

Recent analysis of the sequenced genomes of major trunk disease associated fungi, including N. parvum and D. seriata, revealed an expansion of gene families related to plant cell wall degradation [34]. Approximately 36.6% of the putative secreted peptides in the genomes of eight trunk pathogens were similar to CAZy proteins, with predicted catalytic and carbohydrate-binding domains that can participate in the disassembly of plant cell walls during pathogen attack. The largest superfamily was represented by glycoside hydrolases that include subfamilies involved in the degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose [34].

One of the grapevine responses to wood decay fungi is the production of secondary metabolites called phytoalexins. Phytoalexins are produced after infection with pathogens or recognition of an elicitor in different plant species and can act as markers of resistance [35]. In grapevine, phytoalexins belong essentially to the class of stilbenes synthesized via the phenylpropanoid pathway. The grapevine stilbenes have an antifungal activity [36,37], inhibiting spore germination, fungal penetration, fungal growth and development [38]. The first synthesized stilbene, resveratrol, will be modified in various compounds in grapevine [38,39]. Resveratrol glycosylation will form piceid, which is a non-toxic stilbene that could represent inactive storage form [40,41]. δ- and ε-viniferin are resveratrol dimers synthesized by an oxidation reaction, they are considered as the most toxic forms of stilbenes [42]. Resveratrol methylation will lead to the synthesis of the potent antifungal pterostilbene by a resveratrol O-methyltransferase (ROMT) [42,43]. Together with viniferins, pterostilbene is one of the most toxic stilbene form, 10 fold more toxic than resveratrol [42,43].

In the case of grapevine trunk diseases, accumulation of stilbenes including resveratrol, ε-viniferin and two other resveratrol oligomers, has been shown in the brown-red wood, leaves and berries of esca-diseased grapevines [44–47]. In addition, genes encoding PAL (Phenylalanine Ammonia Lyase) and stilbene synthase (STS), two phenylpropanoid biosynthesis enzymes, were strongly expressed in asymptomatic leaves before the appearance of the esca apoplectic form [48]. Lambert et al. [49] studied the in vitro antifungal activity of different stilbenes on different isolates and species of Botryosphaeriaceae and demonstrated that resveratrol, pterostilbene and ε-viniferin inhibited the growth of Botryosphaeriaceae, especially N. parvum and D. seriata. However, this study also reported that fungi associated with esca, P. minimum, P. chlamydospora and Fomitiporia mediterranea have the ability to grow in media rich in phenolic compounds [49].

The capacity of trunk disease fungi to produce enzymes degrading antifungal metabolites synthesized by the plant cell could play a significant role in the outcome of the interaction between grapevine and pathogens. Oxidation of phenolic compounds can be achieved by laccases, enzymes occuring widely in fungi [50]. Botrytis cinerea, the grey mold agent, produces a laccase-like stilbene oxidase that catalyzes the oxidation of resveratrol in different dimer compounds, in particular δ-viniferin, the most abundant resveratrol dimer [51,52].

Enzymes involved in the oxidation of phenolic compounds are also involved in lignin degradation. Lignin and manganese peroxidases are part of the extracellular oxidative system developed by rot fungi to degrade lignin [53]. The esca associated fungi P. chlamydospora and P. minimum are characterized by different in vitro enzymatic activities such as tannases, laccases and peroxidases activities, and are able to use tannic acid and resveratrol as a carbon source [31,54]. Fomitiporia mediterranea, a fungus associated with the white rot of esca, secretes various lignolytic enzymes, such as laccases, peroxidases and phenol oxidases [25]. Analysis of N. parvum and D. seriata genomes also demonstrated a significant expansion of gene families associated with specific oxidative functions, which may contribute to lignin degradation [34]. The synthesis of enzymes involved in the degradation of starch and lignocellulose has been reported in Botryosphaeria sp. and could be regulated by veratryl alcohol, a secondary metabolite synthesized by fungi [55].

In order to develop effective control strategies against grapevine trunk diseases, it appears necessary to fully identify the factors involved in disease progression and to understand all aspects of their pathogenicity. In a work studying 56 Botryosphaeriales strains, including N. parvum and D. seriata, the authors showed that most strains produced cellulases, laccases, xylanases, pectinases, pectin lyases, amylases, lipases and proteases [56]. Here, the aim of our work was to link B. dieback fungi aggressiveness with a capacity to decay grapevine wood and/or a capacity to detoxify phytoalexins. We focused on different strains of N. parvum and D. seriata, characterized by different aggressiveness levels on grapevine.

We first investigated the ability of secreted fungi proteins to degrade cell wall polysaccharides and lignin by enzymatic activities. We have previously shown that Vitis cells are able to produce stilbenes after detection of secreted proteins from Botryosphaeriaceae [57]. In this work, we also studied the activity of resveratrol and δ-viniferin produced by grapevine on Botryosphaeriaceae fungi growth and we further investigated the ability of these fungi to detoxify them. Stilbene detoxification activity could be an important component of the pathogenicity mechanism of trunk disease fungi.

Material and methods

Fungi

D. seriata 98.1 and N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 were obtained from the collection of the IFV (Institut Français de la Vigne et du Vin, Rodilhan, France). N. parvum Bt-67 was obtained from a single spore collection of the Instituto Superior de Agronomia (Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal). D. seriata 98.1 was isolated in 1998 in Perpignan as described in Larignon et al. (2001) [58]. N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 was isolated in 2009 from Chardonnay plants showing decline in nurseries. N. parvum Bt-67 was isolated from vineyards in Portugal. Fungi were grown in Petri dishes containing PDA (Potato Dextrose Agar) solid medium at 27°C in the dark. The fungi were subcultured every 10 days.

Isolation of total extracellular proteins

Fungi solid cultures were grown for 10 days, then three mycelia plugs for each fungus (2.5 x 2.5 cm) were introduced in a 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 250 mL liquid culture medium. We used 4 different liquid culture media: malt medium, malt medium supplemented with V. vinifera cv. Gewurztraminer sawdust, Erickson and Peterson medium [59], and Ericksson and Peterson medium supplemented with V. vinifera cv. Gewurztraminer sawdust. Liquid cultures were grown at 220 rpm, in the dark and at 28°C. After twenty-one days, culture media were retrieved and sterilized by successive filtrations at 0.8, 0.45 and 0.2 μm.

Total extracellular proteins were precipitated from 250 mL filtered culture medium with 60% (w/v) ammonium sulfate according to [22]. After 2 hours of shaking at 4°C, extracts were centrifuged 30 min at 10 000 rpm and the protein pellets were resuspended in deionized water and dialyzed in 3.5 kDa cutoff tubbing against deionized water for 20 h at 4°C. Collected proteins were freeze dried and resuspended in 3 mL ultra-pure water. The protein concentration was measured with a BioSpec-nano Micro-volume Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu™, Japan) at 280 nm.

Enzymatic activity of wood degradation

The total extracellular protein extract from the different fungi (2 mg.mL-1 total proteins) was used to measure enzymatic activities involved in wood degradation.

Cellulose and arabic gum were used as substrates to measure the cellulase and hemicellulase activity, respectively. Furthermore, V. vinifera cv. Gewurztraminer sawdust was used as a substrate to determine the total polysaccharide degrading activity. Cellulase and hemicellulase activities result in reducing sugar liberation that was further measured with the colorimetric method using 3.5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) [60]. This colorimetric assay estimates the concentration of reducing sugars containing free carbonyl group (eg. glucose, lactose). When an alkaline solution of 3.5-dinitrosalicylic acid reacts with reducing sugars or other reducing substances, it is converted into 3-amino-5-nitrosalicylic acid with orange-red color.

A calibration curve was performed using glucose solution at different concentrations: 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, 20 mM. For each concentration, 60 μL of glucose solutions were added to 60 μL of DNS (10 g.L-1 DNS, 300 g.L-1 sodium potassium tartrate, dissolved in sodium hydroxide at 0.4 N) in a 96-well PCR microplate (ThermoFischer Scientific®, USA). The plate was sealed with an aluminium film (131 x 81.3 mm) and incubated for 5 min at 95° C in order to reduce the DNS. Then, 80 μL of each well was deposited in a new 96-well plate (flat bottom, Sterilin, ThermoFischer Scientific®, USA). The absorbance was measured at 540 nm in a microplate spectrophotometric reader (MCC / 340 2.32, Multiskan®). The calibration curve A540 = f ([glucose mM]) was plotted on Microsoft Office Excel (Microsfot, USA®). The equation of the curve is y = 0.129x and the linear regression coefficient is R2 = 0.9961.

For the measure of enzymatic activity, the protein extracts were first incubated with the different substrates at the same concentration (cellulose, arabic gum and V. vinifera cv. Gewurztraminer sawdust at 55.55 mg.mL-1): 20 μL of each protein extract (containing 40 μg of total proteins) was deposited in a 96-well PCR microplate with a raised skirt (Kisker Biotech GmbH and Co®, Germany) and 180 μL of a buffer solution (50 mM sodium acetate buffer pH 5, 30 μg.mL-1 cycloheximide, 40 μg.mL-1 tetracycline) containing the different substrates (10 mg per well) were added. Two negative controls containing either only the substrate or the protein extracts were performed. The plate was sealed with an aluminium film (131 x 81.3 mm) and incubated for 3 h at 50°C in a thermocycler (Thermocycler Multither, Benchmark Scientific®, USA) with a shaking of 600 rpm. Then, 140 μL of each mixture were transferred to a 96-well filter plate (1 μm, fiberglass, AcroPrep Advance 96 Fliter plate, PALL®, USA), coupled to a 96-well recovery plate (flat bottom, Greiner Bio -one®, Germany) and centrifuged for 5 min at 800 rpm. Recovery plate contents were transferred to a new 96-well PCR microplate (4titude®Ltd, UK) and 60 μL of DNS were added before sealing the microplate with an aluminium film (131 x 81.3 mm). The plate was incubated for 5 min at 95°C. After incubation, 80 μL of each mixture was deposited in a reading plate and the absorbance at 540 nm was determined using a microplate spectrophotometric reader (MCC / 340 2.32, Multiskan®). The concentration of reducing sugars was calculated from the calibration curve equation, and the concentration of reducing sugars of the negative controls was subtracted to the sample values. The results are expressed as the amount of reducing sugars produced (in mol) per g of proteins.

Laccase activity was determined with the ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) substrate. ABTS is oxidized by laccase in its corresponding radical cation ABTS.+, which produced a blue color. For each test, 100 μg of secreted proteins (2 mg.mL-1) were mixed with 50 μL of a solution containing 25 μL ABTS (2 mM) and 25 μL of sodium acetate (100 mM, pH 4.5), and incubated for 30 min at 25°C in a 96-well microplate (flat bottom, Sterilin, ThermoFischer Scientific®, USA). After 30 min, the absorbance at 420 nm was measured with a microplate reader (MCC / 340 2.32, Multiskan®). The obtained absorbance values were converted into enzymatic activity via the ABTS.+ extinction coefficient (36,000 M-1 cm -1) according to [61].

Manganese peroxidase activity was based on the coupling of MBTH and DMAB in the presence of H2O2 and Mn2+ according to [61]. The reaction in the presence of Mn2+ allows to specifically measure the Mn peroxidase activity. We used two solutions, A and B. The solution A contained 0.5 ml of DMAB solution (50 mM), 0.5 mL of MBTH solution (1 mM), 1 mL MnSO4–4H2O solution (1 mM) and 5 mL of sodium lactate and sodium succinate buffer (100 mM each, pH 4.5) for a final volume of 7 mL. The solution B was identical to the solution A except for the MnSO4–4H2O which was replaced by a solution of EDTA (2mM). For the manganese peroxidase assay, 140 μL of solution A or B are mixed with 10 μL of H2O2 (1 mM) and 50 μL of secreted proteins (2mg.mL-1) and incubated for 1 hour at 26°C in a 96-well microplate (flat bottom, Sterilin, ThermoFischer Scientific®, USA). Absorbance at 590 nm was measured with a microplate reader (MCC / 340 2.32, Multiskan®). Mn peroxidase activity was obtained by subtracting the absorbance values obtained with solution B to those obtained with solution A, containing MnSO4. Absorbances were converted into enzymatic activity via the extinction coefficient (32,000 M-1 cm -1).

Chemicals

Trans-resveratrol, lyophilized horseradish peroxidase HRP and hydrogen peroxide (30%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Quentin Fallavier, France). Trans-δ-viniferin was synthetized according to the procedure described below. Cis-isomers of resveratrol and δ-viniferin were obtained by photoisomerization at 350 nm using a Rayonet photochemical reactor (Southern New England Ultraviolet Co.). 25 mM stock solutions of trans-stilbenes were prepared in anhydrous DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) purchased from Alfa Aesar (Karlsruhe, Germany). LC-MS grade water, methanol and formic acid were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Illkirch, France).

For δ-viniferin synthesis, we used general experimental procedures: Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on Merck 60 F254 silica gel. Silica gel 73–230 mesh (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was used for column chromatography. High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HRESI MS) was performed on an Agilent 3100 QTof. FTIR spectra were recorded by ATR technique using Brüker Vertex 70. NMR spectra were recorded at 300 K in deuterated acetone on Brüker Avance 400 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) are indicated in ppm and coupling constants (J) in Hz.

δ-viniferin was synthesized according to a procedure inspired by [62]. 0.7 mg of HRP in 700 μL of phosphate buffer (20 mM pH8) were added to a solution of trans-resveratrol (1.76 mmol, 400 mg) in 1:1 v/v acetone/phosphate buffer 20 mM pH 8 (10 mL.mmol-1). The mixture was stirred at 40°C and 360 μL of 30% H2O2 were added during 40 min. Then, the reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc. The organic layer was washed with water, dried over anhydrous magnesium sulphate and concentrated. The crude product was purified on silica gel column and eluted with dichloromethane:acetone 75:25 (1% v/v NET3). δ-viniferin was obtained as a yellow amorphous powder (60.7 mg, 46% yield). HRESI MS (-) m/z 453.1320 [M-H]- (calcd for C28H21O6 453.1344) 499.1389 [M+HCOOH-H]- calcd for C29H22O8 498.1315); FTIR (ATR) vmax cm−1: 3308, 1596, 1487, 1341, 1234, 1149; 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ = 8.55 (1 H, br. s), 8.29 (1 H, s), 8.26 (1 H, s), 7.43 (1 H, dd, J = 1.8, 8.4 Hz), 7.24 (3 H, m), 7.06 (1 H, d, J = 16.4 Hz), 6.88 (4 H, m), 6.53 (2 H, d J = 2.0 Hz), 6.28 (1 H, t, J = 2.3 Hz), 6.25 (1 H, t, J = 2.0 Hz), 6.198 (2 H, d, J = 2.3 Hz), 5.45 (1 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 4.46 (1 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz). 13C NMR (100 MHz, acetone-d6) δ = 160.7, 159.9, 159.7, 158.6, 145.3, 140.8, 132.6, 132.3, 131.8, 129.2, 128.7, 128.7, 127.3, 124.0, 116.3, 110.2, 107.5, 105.8, 102.8, 102.5, 94.1, 57.9. Spectral data are in agreement with the literature [63].

Fungi growth inhibition tests

The fungistatic activity of resveratrol and δ-viniferin was tested on N. parvum Bourgogne S-116, N. parvum Bt-67 and D. seriata 98.1. Stilbenes were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO. Stilbenes (50 μM or 250 μM final concentration) or the same volume of DMSO (negative control) was added to PDA medium at a final concentration of 1%. After 10 days of growth on PDA alone medium, mycelia plugs of 5 mm diameter were transferred at the center of a new Petri Dish containing PDA medium and stilbenes in DMSO or DMSO alone. Petri dishes were incubated at 26°C in the dark and pictures were taken each day from 48 h after inoculation until Petri dish saturation. Mycelia area was measured with ImageJ software [64]. For each condition, 3 technical replicates and 2 biological replicates were performed.

Metabolite extraction

PDA culture medium of fungi grown in the presence or absence of stilbenes (concentration of 50 μM) was extracted at 3, 6, 10 or 11 days with ethyl acetate (3 x 50 mL, 24h with stirring at room temperature). The supernatant was filtered and evaporated with a rotary evaporator. The extract was dissolved in 1 mL methanol, filtered with a 0.2 μm PTFE filter, and kept at -20°C until LC-MS analysis. A 10-fold dilution in methanol was used for analysis.

LC-MS analysis

The analytical system used was High Performance Liquid Chromatography Agilent 1100 series coupled to Agilent 6510 accurate-mass Quadrupole-Time of Flight (Q-TOF) Mass spectrometer with ESI interface in negative ionization mode (Agilent Technologies, California, USA). Data acquisition system software was Agilent MassHunter version B.02.00. A Zorbax SB-C18 column (3.1×150 mm, ∅ 3.5 μm), equipped with a 2.1x12.5 mm ∅ 5 μm Zorbax Eclipse plus C18 precolumn (Agilent Technologies), was used at 35°C and the injected volume was 2 μL. The elution gradient was carried out with binary solvent system consisting of 0.1% formic acid in H2O (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in MeOH (solvent B) at a constant flow-rate of 0.35 mL.min-1. The gradient elution program was as follows: 0−3.0 min, 5% B; 3.0−23.0 min, up to 100% B; held for 10.0 min, followed by 7 min of stabilization at 5% B.

The mass spectrometer operated by detection in scan mode with the following settings: drying gas 13.0 L.min-1 at 325°C; nebulizer pressure 35 psi; capillary voltage -3500 V, fragmentor 150 V. Negative mass calibration was performed with standard mix G1969-85000 (Agilent Technologies).

Data processing was performed with Agilent MassHunter Qualitative and Quantitative software version B.07.00. Absolute stilbene contents were estimated from external calibration curves prepared with pure standards.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by using a multifactorial ANOVA and a multiple comparison of means using the Tukey test (p ≤ 0,05) performed with R 3.3.2 software (R Development Core Team 2017; [65]).

Results

Polysaccharide degrading enzymatic activities of N. parvum and D. seriata

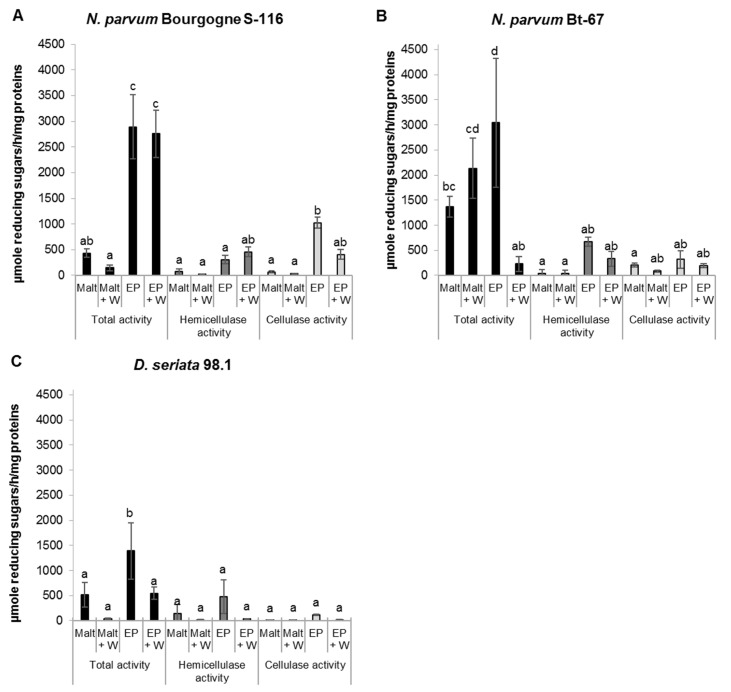

We first evaluated three different enzymatic activities: cellulase, hemicellulase, and total polysaccharide degrading activities of secreted proteins produced by N. parvum Bourgogne S-116, N. parvum Bt-67 and D. seriata 98.1 (Fig 1). We observed a higher total polysaccharide degrading activity with grapevine sawdust as substrate compared to the activity on other substrates (arabic gum and cellulose). Total polysaccharide degrading enzymatic activity was also higher for N. parvum compared to D. seriata (Fig 1) and higher when fungi were cultured in EP medium (minimum medium) compared to malt (rich) medium. Proteins secreted by N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 presented weak enzymatic activities when the fungus was grown in malt medium, whereas total and cellulase activities were significantly enhanced in minimum EP medium (Fig 1A). In contrast, proteins secreted by N. parvum Bt-67 presented similar enzymatic activities when the fungus was grown in rich malt medium or minimum EP medium (Fig 1B). Finally, D. seriata 98.1 secreted proteins had lower enzymatic activities (total, cellulase, hemicellulase) (Fig 1C). Generally, the enrichment of fungi culture medium with V. vinifera sawdust does not have a significant effect on the protein activities, except for N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 (Fig 1A).

Fig 1. Polysaccharide degrading enzymatic activities.

Glucose liberation resulting from cellulase, hemicellulase and total activities of secreted proteins from N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 (A), N. parvum Bt-67 (B) and D. seriata 98.1 (C), was measured with a colorimetric method using dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS). Total proteins were isolated from culture filtrates of fungi grown in liquid malt medium (Malt), malt medium supplemented with V. vinifera sawdust (Malt + W), Erickson and Peterson medium (EP) and Erickson and Peterson medium supplemented with V. vinifera sawdust (EP + W). Values are means and SD of three biological replicates, each calculated from the mean of three technical replicates. Means with a same letter are not significantly different at p≤0.05 (Tukey Contrasts).

Lignin degrading enzymatic activities of N. parvum and D. seriata

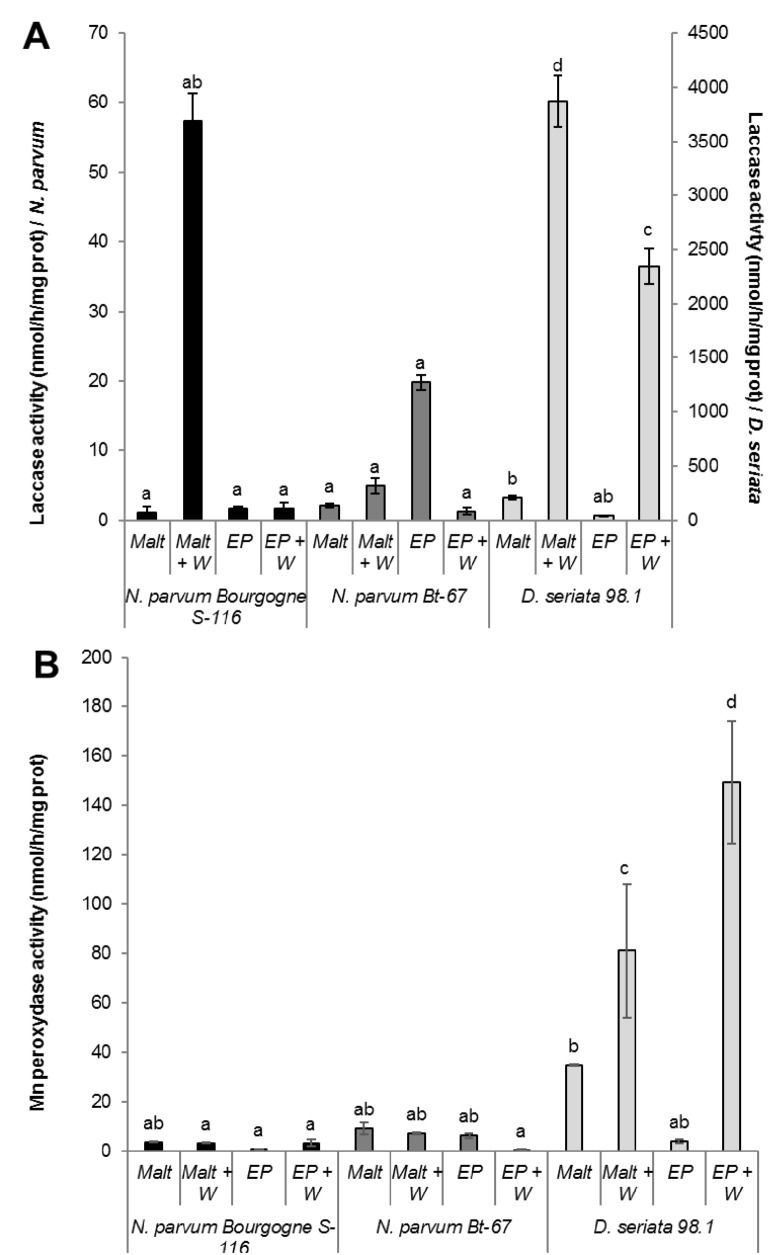

It is assumed that lignin degradation is initiated by the attack of laccases, manganese peroxidases and lignin peroxidases. Interestingly, laccase activity was significantly stronger for D. seriata 98.1 secreted proteins, especially when cultured in malt or EP media supplemented with V. vinifera sawdust (Fig 2A). In N. parvum Bourgogne S-116, the laccase activity was also enhanced when fungus was grown in malt medium supplemented with sawdust. The lowest laccase activity was measured for N. parvum Bt-67 (Fig 2A). Overall, the laccase activity measured in D. seriata was approximately 100-fold higher compared to N. parvum. We also evaluated manganese peroxidase activity of Botryosphaeriaceae secreted proteins with the MBTH/DMAB colorimetric method. As seen for laccase activity, manganese peroxidase activity was significantly higher for D. seriata 98.1 secreted proteins and especially when grown in malt or EP media supplemented with V. vinifera sawdust (Fig 2B). The manganese peroxidase activity measured in D. seriata was approximately 15-fold higher compared to N. parvum. In contrast with laccase activity, the lowest Mn peroxidase activity was measured for N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 and not for N. parvum Bt-67.

Fig 2.

(A) Laccase activity. Oxidation of ABTS in the radical cation ABTS.+ was measured with total secreted proteins from N. parvum Bourgogne S-116, N. parvum Bt-67 and D. seriata 98.1. Total proteins were isolated from culture filtrates of fungi grown in malt medium (Malt), malt medium supplemented with V. vinifera sawdust (Malt + W), Erickson and Peterson medium (EP) and Erickson and Peterson medium supplemented with V. vinifera sawdust (EP + W). (B) Manganese peroxidase activity. Oxidation coupling of MBTH/DMAB was measured in presence of H2O2 and Mn2+. Total proteins were isolated from culture filtrates of fungi grown in liquid malt medium (Malt), malt medium supplemented with V. vinifera sawdust (Malt + W), Erickson and Peterson medium (EP) and Erickson and Peterson medium supplemented with V. vinifera sawdust (EP + W). Values are means and SD of three biological replicates, each calculated from the mean of two technical replicates. Means with a same letter are not significantly different at p≤0,05 (Tukey Contrasts).

δ-viniferin has fungistatic activity on N. parvum

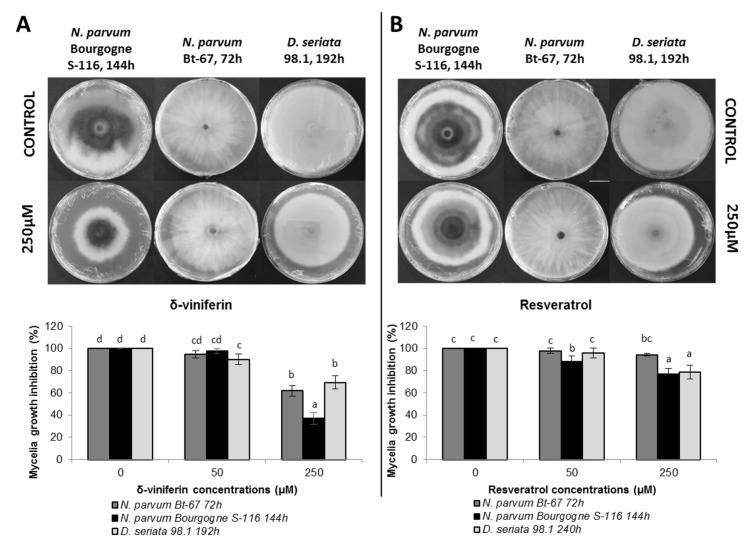

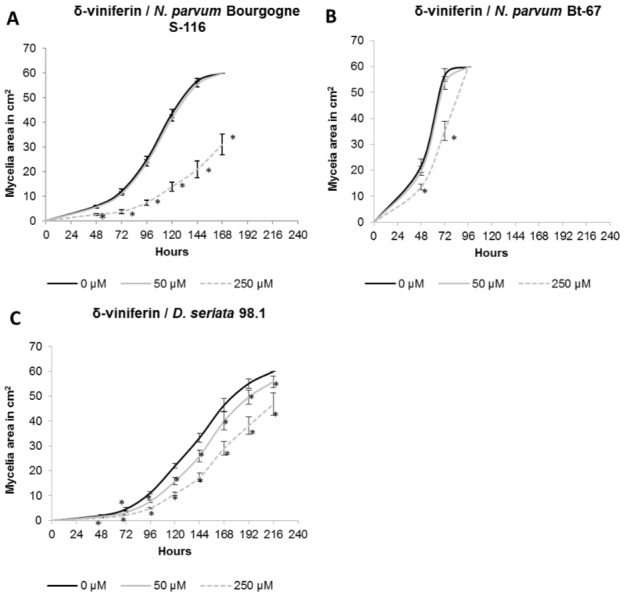

We have previously shown that δ-viniferin is the most abundant stilbene produced after treatment of grapevine suspension cells with Botryosphaeriaceae secreted proteins. To test if this compound could be active in inhibiting Botryosphaeriaceae mycelial growth, δ-viniferin was added to the solid culture medium of N. parvum Bourgogne S-116, N. parvum Bt-67 and D. seriata, at 50 and 250 μM. Activity of δ-viniferin was compared to the activity of resveratrol which was added at the same concentrations. The addition of 250 μM δ-viniferin in the fungi culture medium resulted in a significant inhibition of N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 mycelial growth from 48 to 168 hours after inoculation (50% inhibition at 168 h compared to control; Fig 3A). δ-viniferin also induced a weaker but significant inhibition of D. seriata 98.1 growth both at 50 μM (7% inhibition at 216 h compared to control, Fig 3C) and 250 μM (22% inhibition at 216 h compared to control, Fig 3C). δ-viniferin only induced a slight delay in N. parvum Bt-67 mycelial growth (30% inhibition at 72 h and 250 μM compared to control, Fig 3B) and after 96 h, this inhibition was no more observable (Fig 3B).

Fig 3. Effect of δ-viniferin on Botryosphaeriaceae.

The δ-viniferin was tested at a final concentration of 50 μM (grey lines) and 250 μM (gray dotted lines) on N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 (A), N. parvum Bt-67 (B) and D. seriata 98.1 (C) growth. δ-viniferin was dissolved in DMSO and negative control was performed by adding DMSO alone. Values are means and SD of two biological replicates, each calculated from the mean of three technical replicates. Means with a * are significantly different from control at p ≤ 0.05 (Tukey Contrasts).

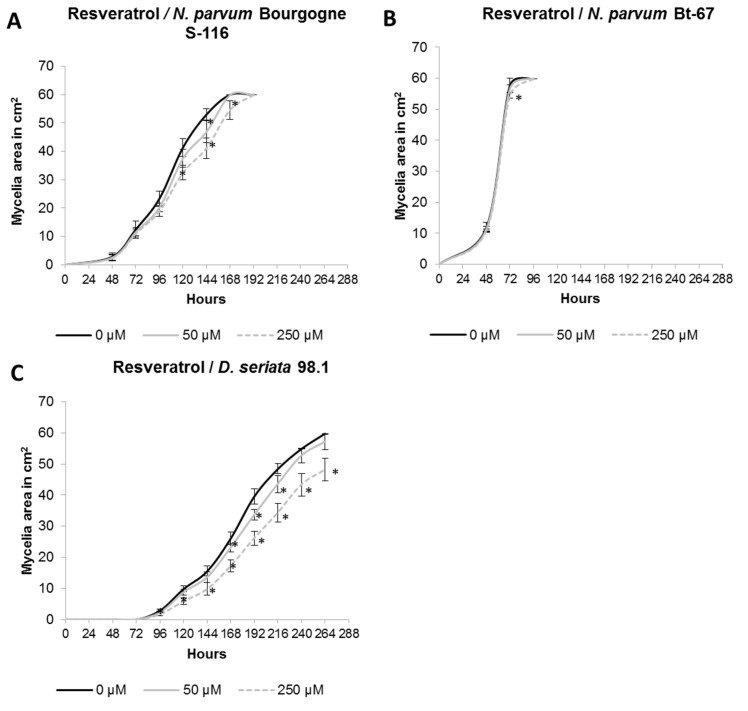

In contrast to δ-viniferin, resveratrol only induced a delay in the mycelial growth for both N. parvum isolates, and at the end of the experiment, no inhibition was observable (Fig 4A and 4B). However, for D. seriata 98.1, we observed a slight but significant inhibition after the addition of resveratrol at a final concentration of 250 μM (19.5% inhibition compared to control at 264 h; Fig 4C).

Fig 4. Effect of resveratrol on Botryosphaeriaceae.

The resveratrol was tested at a final concentration of 50 μM (grey lines) and 250 μM (gray dotted lines) on mycelial growth of N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 (A), N. parvum Bt-67 (B) and D. seriata 98.1 (C). Negative control was performed by adding DMSO instead of resveratrol. Values are means and SD of two biological replicates, each calculated from the mean of three technical replicates. Means with a * are significantly different from control at p ≤ 0,05 (Tukey Contrasts).

To take into account the difference of growth rate between the different fungi strains in the comparison of δ-viniferin and resveratrol activities, mycelium surface was measured when the fungi have nearly colonized all the petri dish for control conditions (one day before saturation). The results are similar to those obtained in Figs 3 and 4. It appears that δ-viniferin has a strong effect in inhibiting N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 growth, a weak effect on D. seriata and no significant effect on N. parvum Bt-67 (Fig 5A). Concerning resveratrol, it shows a low activity on both N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 and D. seriata 98.1 growth, whereas N. parvum Bt-67 is not significantly affected (Fig 5B). In conclusion, N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 is the most susceptible to stilbene activity, followed by D. seriata and N. parvum Bt-67.

Fig 5. Comparison of the effect of δ-viniferin and resveratrol on Botryosphaeriaceae.

Effect of δ-viniferin (A) and resveratrol (B) on mycelial growth of N. parvum BourgogneS-116, N. parvum Bt-67 and D. seriata 98.1. Pictures were taken at different time points, when the fungi have nearly colonized all the Petri dish for control conditions (one day before saturation). Values are means and SD of two biological replicates, each calculated from the mean of three technical replicates. Means with a same letter are not significantly different at p≤0.05 (Tukey Contrasts).

Botryosphaeriaceae are able to metabolize resveratrol and δ-viniferin

To know if Botryosphaeriaceae fungi are able to metabolize stilbenes, we further analyzed the evolution of resveratrol and δ-viniferin (initially added at 50 μM) remaining in the fungi culture medium by LC-MS. Since degradation also occurred in the control culture medium (without fungi), quantities of remaining stilbenes were calculated as a percentage of the quantity found in control culture medium after 3, 6 and 11 days of culture.

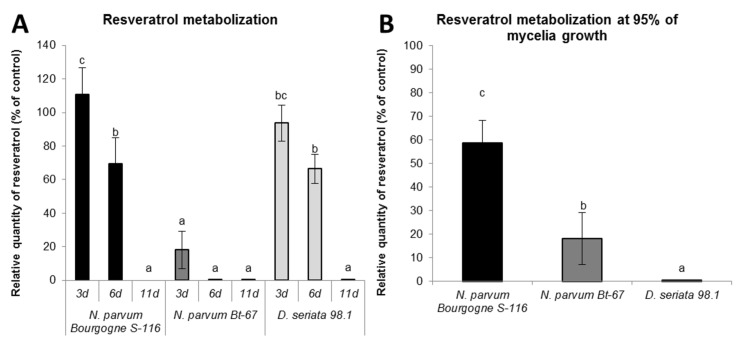

The Fig 6A shows a rapid decrease in resveratrol for all fungi, that has the same pattern for N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 and D. seriata 98.1: approximately 30% of resveratrol found in control culture medium was degraded after 6 days and after 11 days a very low quantity of resveratrol was detected. In N. parvum Bt-67 medium, there is already a low level of resveratrol after 3 days of growth. Since the growth rate is different between the different Botryosphaeriaceae, the Fig 6B shows the relative quantity of resveratrol remaining when the fungus is at 95% of the petri dish saturation. We observed significant differences in the remaining resveratrol between the fungi (p ≤ 0,0001). In the medium of D. seriata 98.1, there is almost no more remaining resveratrol (0.45% of initially added resveratrol), in contrast to N. parvum Bt-67 medium where 18% of added resveratrol was detected. In N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 medium, remaining resveratrol quantity is much higher compared to D. seriata (59%,Fig 6B).

Fig 6. Resveratrol metabolization by Botryosphaeriaceae fungi.

Resveratrol (initially added at 50 μM) was quantified by LC-MS in PDA medium extract of N. parvum Bourgogne S-116, N. parvum Bt-67 and D. seriata 98.1. The resveratrol quantity is expressed in relative quantity (% of control) compared to control medium without fungi at different time points (3, 6 and 11 days; A), or when fungi have saturated 95% of the Petri Dish surface (B). Values are means and SD of three biological replicates, each calculated from the mean of three technical replicates. Means with a same letter are not significantly different at p≤0.05 (Tukey Contrasts).

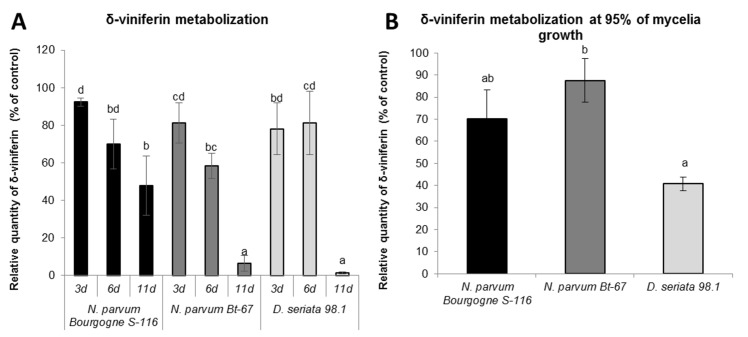

Concerning δ-viniferin, Fig 7A shows a decrease over time in the medium of the two N. parvum isolates and of D. seriata 98.1. However, δ-viniferin metabolization seems less rapid compared to resveratrol. The reduction in δ-viniferin has the same pattern for the two N. parvum isolates at 3 days (approximately 85% remaining) and 6 days (65% remaining). After 11 days, a significant proportion of δ-viniferin was measured for N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 (48% of control), whereas almost all δ-viniferin was metabolized for N. parvum Bt-67 (6.4% of control). For D. seriata 98.1, the quantity of δ-viniferin was stable from 3 to 6 days of growth (80% of control) and drop after 6 days (1.5% of control). Measures of remaining δ-viniferin at nearly Petri dish saturation (Fig 7B) demonstrated a less marked difference between the fungi (p ≤ 0.05). However, the medium of D. seriata 98.1 contained the lowest quantity of remaining δ-viniferin compared to N. parvum isolates.

Fig 7. δ-viniferin metabolization by Botryosphaeriaceae fungi.

δ-viniferin (initially added at 50 μM) was quantified by LC-MS in PDA medium extract of N. parvum Bourgogne S-116, N. parvum Bt-67 and D. seriata 98.1. The δ-viniferin quantity is expressed in relative quantity (% of control) compared to control medium without fungi at different time points (3, 6 and 11 days: A), or when fungi have saturated 95% of the Petri Dish surface (B). Values are means and SD of three biological replicates, each calculated from the mean of three technical replicates. Means with a same latter are not significantly different at p≤0,05 (Tukey Contrasts).

Discussion

In this work, we first investigated the wood degradation capacity of N. parvum and D. seriata, two major fungi associated with Botryosphaeria dieback, focusing on their extracellular enzymatic material. We also investigated the effect of two major grapevine phytoalexins, resveratrol and δ-viniferin on the growth of these trunk disease fungi. These phytoalexins have been previously described as inefficient against some Botryosphaeria isolates [66,49]. The ability of Botryosphaeriaceae fungi to metabolize grapevine stilbenes was thus further studied.

In forest ecosystems, fungi acting as decomposers play major roles in dead wood degradation mediated by extracellular enzymatic systems. Decomposer fungi produce a wide range of extracellular lignolytic enzymes and are divided in three major groups according to their mode of attack on the woody cell walls: soft-rot fungi, brown-rot fungi and white-rot fungi (for review, see [59]). It has been reported that soft rot fungi primarily degrade the carbohydrate components of cell walls and lignin to a lesser extent [67]. In the case of trunk diseases, E lata is the only fungus that was classified as a soft rot, a term used to describe all forms of decay caused by ascomycetes [30].

There are few reports on the characterization of enzymatic wood-degrading activity of B. dieback pathogens, although it could bring to light some elements regarding the aggressiveness of N. parvum and D. seriata. In a previous study, different authors studied the enzymatic arsenal of 56 strains of Botryosphaeriales, including N. parvum and D. seriata [56]. They showed that most strains produced cellulases, laccases, xylanases, pectinases, pectin lyases, amylases, lipases and proteases. However, these enzymatic activities were not associated with any particular species or phylogenetic group [56].

In the present study, we compared secreted wood degradation enzymatic activities of different isolates of B. dieback fungi, with different aggressiveness levels. According to [56], we show that both N. parvum and D. seriata are able to degrade the carbohydrate components of cell walls and exhibit hemicellulase and cellulase activities, that could explain at least 60% of the wood decay (cellulose and hemicellulose) [68]. Our data also show that N. parvum has higher total enzymatic activity of polysaccharide degradation compared to D. seriata. Compared to D. seriata, total polysaccharide degrading activity was higher in N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 grown in EP and EP supplemented with wood medium and in N. parvum Bt-67 grown in malt, malt supplemented with wood and EP media (Fig 1). This result could be related to a higher growth of N. parvum after artificial wood inoculation already shown by various authors [19,20,69,9,70,71,23,72]. Our results are also consistent with the trunk disease fungi genome analysis of Morales et al [34], showing that ascomycete trunk pathogens have a wider array of enzymes that target cellulose and hemicellulose compared to other grapevine pathogens. In this study, proteins secreted by both N. parvum and D. seriata exhibited a higher enzymatic activity when grown in a minimum medium (EP), in comparison to a rich medium (malt), supposing that adaptation to a poor environment goes through a strongest enzymatic activity, in order to exploit and extract efficiently the nutrients. This was especially significant for N. parvum Bourgogne S-116, as the total activity was 5 to 8 fold higher in EP medium compared to activity in malt medium.

Concerning lignin degradation, it is assumed that it is initiated by the attack of lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase and laccase secreted by white rot fungi [61]. In our study, we were also interested in laccase and Mn peroxidase activities of Botryosphaeriaceae secreted proteins. Strikingly, a significantly stronger laccase activity was measured for D. seriata compared to N. parvum. Compared to N. parvum, laccase activity was approximately 100 fold higher for D. seriata grown in malt or EP medium supplemented with wood. Concerning N. parvum, laccase activity was higher in Bourgogne S-116 isolate compared to Bt-67 (Fig 2A). Whereas addition of grapevine sawdust to the fungi culture medium did not induce a higher carbohydrate degrading enzymatic activity, it significantly enhanced both laccase and Mn peroxidase activities, especially for D. seriata. In another study assessing different extracellular enzymatic activities involved in the wood decaying process in different rot type fungi, addition of sawdust did not result in higher enzymatic activities [61].

Characterization of laccase activity in Botryosphaeriaceae is consistent with genome analysis of N. parvum and D. seriata that revealed an expansion of auxiliary activity CAZymes 1 genes, encoding multicopper oxidases including laccases, which participate in the deconstruction of lignocellulosic material [34]. A previous study also showed that some Botryosphaeria sp. are able to degrade lignocellulose. Moreover lignin degradation could be enhanced by veratryl alcohol, a fungi metabolite, via laccase regulation [55].

Our study also underlines that even if a similar gene expansion was evidenced in both N. parvum and D. seriata, a higher laccase activity was measured in D. seriata. We also show that D. seriata is characterized by a stronger Mn peroxidase activity, approximately 10 fold higher compared to N. parvum (Fig 2B). Laccases and peroxidases could be involved in degradation of new lignin and polyphenolic compounds deposited in response to infection. Phenol oxidases produced by D. seriata could thus participate in breakdown of newly wall bound lignin after infection. It is interesting to point out that association of two major B. dieback fungi (N. parvum and D. seriata) could be very efficient in the degradation of the lignocellulosic material.

The enzymatic wood degradation activity has been described for other fungi associated with esca (P. minimum and P. chlamydospora) and for E. lata, responsible for Eutypa dieback. E. lata was shown to target carbohydrate polymers of cell walls [30]. Concerning esca disease, it has been reported that P. minimum possessed enzyme activities responsible for the degradation of polysaccharides (xylanase, exo- and endo-β-1.4-glucanase and β-glucosidase), whereas no ligninase activity was measured [31]. P. chlamydospora was characterized by a pectinolytic activity enabling to circulate through the vessels without degrading the membrane [32,33]. Moreover, F. mediterranea, which is associated with esca white rot symptoms of mature vines, secreted lignolytic enzymes to complete the wood degradation initiated by P. minimum and P. chlamydospora [25,73]. For example, a 60 kDa extracellular laccase has been purified from F. mediterranea and exhibited oxidase activity towards several polyphenolic compounds [74].

In another part of this work, we studied the effect of stilbenes on Botryosphaeriaceae fungi growth. It has been previously demonstrated that grapevine stilbenes have an antifungal activity [36,37], inhibiting spore germination, fungal penetration, fungal growth and development [38]. Based on growth inhibition tests in vitro, δ-viniferin is one of the most toxic stilbene on grapevine pathogens [38,42]. In a previous study, we have shown that treatment of grapevine cell suspensions with secreted Botryosphaeriaceae proteins resulted in a high accumulation of δ-viniferin [52]. In this work, we tried to determine if stilbene production by grapevine represents a real chemical barrier for the progression of B. dieback fungi. Here we show that growth of fungi in the presence of resveratrol (250 μM) resulted in a slight delay for N. parvum growth and in a weak inhibition for D. seriata growth (Fig 4). In contrast, addition of 250 μM δ-viniferin in the culture medium significantly inhibited the growth of N. parvum Bourgogne S-116, (50% inhibition at day 7) and to a lesser extent that of D. seriata (22% inhibition at day 9). δ-viniferin had no significant activity on N. parvum Bt-67 strain. These results show that N. parvum Bourgogne S-116, which was characterized as a very aggressive strain by secreting active toxins triggering cell death in grapevine calli [22], is also the more susceptible to stilbenes, especially δ-viniferin. The ability of Botryosphaeriaceae fungi to grow in the presence of stilbenes strongly suggests that these fungi have the ability to metabolize and degrade these metabolites. Indeed, we further demonstrate that all fungi strains were able to degrade almost all the resveratrol added at 50 μM to the culture medium after 11 days (Fig 6). At earlier time point (6 days), approximately 30% of resveratrol was degraded by N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 and D. seriata 98.1. Among the three fungi strains, N. parvum Bt-67 is the fungi that metabolizes resveratrol the more rapidly, levels of this stilbene being very low compared to control (18%) as soon as after 3 days of culture (Fig 6). Resveratrol was not metabolized in other known stilbenes, since resveratrol-derived compounds were not found in the fungi culture medium (data not shown). Compared to resveratrol, δ-viniferin was metabolized less rapidly. 30, 42 and 20% of added δ-viniferin were degraded after 6 days for N. parvum Bourgogne S-116, N. parvum Bt-67 and D. seriata 98.1 respectively. After 11 days, N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 was the fungi that degraded the less viniferin (52% remaining compared to control), followed by N. parvum Bt-67 (93.5% of degradation) and D. seriata (98.5% of degradation). It is interesting to note that inhibition of N. parvum Bourgogne S-116 growth (50% compared to control) by δ-viniferin is correlated with a lower δ-viniferin degrading activity. It is also likely that laccase and peroxidase activities that were identified in D. seriata and to a lesser extent in N. parvum participate in both resveratrol and δ-viniferin metabolization. The high laccase activity evidenced in D. seriata could explain the very low levels of both stilbenes after 11 days of growth (Fig 2A). In contrast, N. parvum Bt-67 is able to metabolize both resveratrol and δ-viniferin but is characterized by lower laccase and peroxidase activities compared to D. seriata, suggesting that this fungus has other enzymatic systems of phenolic metabolization.

Our results are consistent with other studies reporting that resveratrol was not very inhibitory to the growth of two different grapevine pathogens, Plasmopara viticola and Botrytis cinerea [75], whereas it inhibited the growth of Phomopsis viticola, but with a relatively low activity [42]. Pterostilbene and δ-viniferin were also previously described as the most effective on P. viticola [76–78]. Similarly, resveratrol had no inhibitory activity on E. lata growth, even at high concentration (4400 μM, [79]).

In a detailed study focusing on the in vitro antifungal activity of different phenolics towards trunk disease fungi, it was shown that Botryosphaeriaceae strains are generally sensitive to stilbenes at a 500 μM concentration [49]. However, among the different Botryosphaeriaceae strains, N. parvum was less affected than D. seriata that was more severely inhibited by stilbenoids, especially piceatannol, pterostilbene and ɛ-viniferin. The IC50 of ɛ-viniferin on D. seriata was evaluated at 250 μM [49]. Differences in fungi sensitivity towards stilbenes between our study and the study from Lambert et al. [49] could be explained by the use of a higher stilbene concentration (500 μM compared to 250 μM in our study) and the test of different N. parvum strains. Moreover, the activity of δ-viniferin was not evaluated in the above discussed work. In agreement with our experiments, stilbene activity was shown fungistatic and not fungicidal [49]. In another study [66], Djoukeng et al performed a disk diffusion antifungal assay and reported that stilbenoids (resveratrol, ε- and δ-viniferin) had no effect on D. seriata.

It should be pointed out that dimerization of resveratrol to δ-viniferin can be realized by fungi, such as Botrytis cinerea [52], and in the presence of purified laccases of Trametes versicolor, associated with white rot [80]. Diplodia seriata was also described as able to oxidize wood δ-resveratrol into the dimer δ-viniferin [66]. However, we were not able to detect any δ-viniferin in the medium of fungi supplemented with resveratrol. Furthermore, our results show that δ-viniferin seems to be degraded by Botryosphaeriaceae fungi.

To summarize, our study provides a better understanding of aggressiveness factors expressed by two major Botryosphaeriaceae. Each B. dieback associated fungi is characterized by a specific signature of secondary metabolites and secreted toxic protein production [22,27] and by differential wood decay enzymatic activity equipment (this work). The specific signature of Botryosphaeriaceae aggressiveness factors could explain the importance of fungi complexes in putative synergistic activity in order to fully colonize the host. N. parvum has a more efficient enzymatic activity for cellulose and hemicellulose degradation, whereas D. seriata has a more efficient enzymatic activity for lignin degradation. In addition, B. dieback associated fungi have the capacity to rapidly degrade stilbenes, and this capacity is likely important for the fungi aggressiveness. Indeed, D. seriata growth in the wood is slow, but higher laccase and peroxidase activities could enable this fungus to circumvent phytoalexin production and lignin barriers. Wood and phenolic compound decay enzymatic activities could explain that even if grapevine is able to perceive the invaders and to mount defense responses such as stilbene synthesis and cell wall reinforcement, B. dieback fungi are able to bypass these chemical and physical barriers. It would be interesting to further study the composition of cell wall polymers in susceptible vs tolerant trunk disease grapevine varieties.

Supporting information

Table A: Data for polysaccharide degrading enzyme activities (Fig 1). Table B: Data for laccase and peroxidase activities (Fig 2). Table C: data of fungi growth in media containing viniferin (Fig 3). Table D: data of fungi growth in medium containing resveratrol (Fig 4). Table E: data of fungi growth in media containing δ-viniferin or resveratrol, one day before Petri dish saturation (Fig 5). Table F: data of resveratrol metabolization (Fig 6). Table G: data of δ-viniferin metabolization (Fig 7).

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Pr. Eric Gelhaye, from UMR1136 IaM Interactions Arbres/Micro-organismes in INRA Nancy, for helping with the colorimetric method using DNS as substrate for measuring polysaccharide degrading enzymatic activities.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

E. Stempien PhD fellowship was financed by the Alsace Region (France) and CIVA (Conseil Interprofessionnels des Vins d’Alsace). This work has been supported by Interreg Rhin Supérieur V project "Vitifutur" http://www.interreg-rhin-sup.eu/projet/vitifutur-reseau-transnational-de-recherche-et-de-formation-en-viticulture/. This work has been supported by the Université de Haute Alsace (Ecovino Project). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bertsch C, Ramírez-Suero M, Magnin-Robert M, Larignon P, Chong J, Abou-Mansour E, et al. Grapevine trunk diseases: Complex and still poorly understood. Plant Pathol. 2013;62: 243–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2012.02674.x [Google Scholar]

- 2.De la Fuente M, Fontaine F, Gramaje D, Armengol J, Smart R, Nagy ZA, et al. Grapevine trunk diseases. A review. 1st Edition. Paris, FRance: OIV publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofstetter V, Buyck B, Croll D, Viret O, Couloux A, Gindro K. What if esca disease of grapevine were not a fungal disease? Fungal Divers. 2012;54: 51–67. doi: 10.1007/s13225-012-0171-z [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rovesti L, Montermini A. Un deperimento della vite causato da Sphaeropsis malorum diffuso in provincia di Reggio Emilia. Inf Fitopatol. 1987;37: 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larignon P, Dubos B. Le Black Dead Arm: Maladie nouvelle à ne pas confondre avec l’esca. Phytoma. 2001;538: 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larignon P. Maladies cryptogamiques du bois de la vigne: Symptomatologie et agents pathogènes [Internet]. 2012. [cited 19 Jan 2017]. Available: http://www.vignevin.com/menu-haut/actualites/article.html?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=368&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=918&cHash=2c0eccd030 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Úrbez-Torres JR. The status of Botryosphaeriaceae species infecting grapevines. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2011;50: 5–45. doi: 10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-9316 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor A, Hardy GESJ, Wood P, Burgess T. Identification and pathogenicity of Botriyosphaeria species associated with grapevine decline in Western Australia. Australas Plant Pathol. 2005;34: 187–195. doi: 10.1071/AP05018 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luque J, Martos S, Aroca A, Raposo R, Garcia-Figueres F. Symptoms and fungi associated with declining mature grapevine plants in northeast Spain. J Plant Pathol. 2009;91: 381–390. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larignon P, Fontaine F, Farine S, Clément C, Bertsch C. Esca et Black Dead Arm: Deux acteurs majeurs des maladies du bois chez la vigne. C R Biol. 2009;332: 765–783. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2009.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spagnolo A, Larignon P, Magnin-Robert M, Hovasse A, Cilindre C, Van Dorsselaer A, et al. Flowering as the most highly sensitive period of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. cv Mourvèdre) to the Botryosphaeria dieback agents Neofusicoccum parvum and Diplodia seriata infection. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15: 9644–9669. doi: 10.3390/ijms15069644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crous PW, Slippers B, Wingfield MJ, Rheeder J, Marasas WFO, Philips AJL, et al. Phylogenetic lineages in the Botryosphaeriaceae. Stud Mycol. 2006;55: 235–253. doi: 10.3114/sim.55.1.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pennycook SR, Samuels GJ. Botryosphaeria and Fusicoccum species associated with ripe fruit rot of Actinidia deliciosa (kiwifruit) in New Zealand. Mycotaxon. 1985;24: 445–458. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shoemaker RA. Conidial states of some species on Vitis and Quercus. Can J Bot. 1964;42: 1297–1301. doi: 10.1139/b64-122 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehoczky J. Black dead-arm disease of grapevine caused by Botryosphaeria stevensii infection. Acta Phytopathol Acad Sci Hung. 1974;9: 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cristinzio G. Gravi attacchi di Botryosphaeria obtusa su vite in provincia di Isernia. Inf Fitopatol. 1978; Available: http://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=US201302836605 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuntzmann P, Villaume S, Larignon P, Bertsch C. Esca, BDA and Eutypiosis: foliar symptoms, trunk lesions and fungi observed in diseased vinestocks in two vineyards in Alsace. Vitis. 2010;49: 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guarnaccia V, Vitale A, Cirvilleri G, Aiello D, Susca A, Epifani F, et al. Characterisation and pathogenicity of fungal species associated with branch cankers and stem-end rot of avocado in Italy. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2016;146: 963–976. doi: 10.1007/s10658-016-0973-z [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niekerk JM van, Crous PW, Groenewald JZ (Ewald), Fourie PH, Halleen F. DNA phylogeny, morphology and pathogenicity of Botryosphaeria species on grapevines. Mycologia. 2004;96: 781–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martos S, Andolfi A, Luque J, Mugnai L, Surico G, Evidente A. Production of phytotoxic metabolites by five species of Botryosphaeriaceae causing decline on grapevines, with special interest in the species Neofusicoccum luteum and N. parvum. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2008;121: 451–461. doi: 10.1007/s10658-007-9263-0 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramírez-Suero M, Bénard-Gellon M, Chong J, Laloue H, Stempien E, Abou-Mansour E, et al. Extracellular compounds produced by fungi associated with Botryosphaeria dieback induce differential defence gene expression patterns and necrosis in Vitis vinifera cv. Chardonnay cells. Protoplasma. 2014;251: 1417–1426. doi: 10.1007/s00709-014-0643-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bénard-Gellon M, Farine S, Goddard ML, Schmitt M, Stempien E, Pensec F, et al. Toxicity of extracellular proteins from Diplodia seriata and Neofusicoccum parvum involved in grapevine Botryosphaeria dieback. Protoplasma. 2015;252: 679–687. doi: 10.1007/s00709-014-0716-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellée A, Comont G, Nivault A, Abou‐Mansour E, Coppin C, Dufour MC, et al. Life traits of four Botryosphaeriaceae species and molecular responses of different grapevine cultivars or hybrids. Plant Pathol. 2017;66: 763–776. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12623 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larignon P, Dubos B. Fungi associated with esca disease in grapevine. Eur J Plant Pathol. 1997;103: 147–157. doi: 10.1023/A:1008638409410 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mugnai L, Graniti A, Surico G. Esca (black measles) and Brown Wood-Streaking: Two old and elusive diseases of grapevines. Plant Dis. 1999;83: 404–418. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1999.83.5.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andolfi A, Mugnai L, Luque J, Surico G, Cimmino A, Evidente A. Phytotoxins produced by fungi associated with grapevine trunk diseases. Toxins. 2011;3: 1569–1605. doi: 10.3390/toxins3121569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abou-Mansour E, Débieux J-L, Ramírez-Suero M, Bénard-Gellon M, Magnin-Robert M, Spagnolo A, et al. Phytotoxic metabolites from Neofusicoccum parvum, a pathogen of Botryosphaeria dieback of grapevine. Phytochemistry. 2015;115: 207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larignon P. Contribution à l’identification et au mode d’action des champignons associés au syndrome de l’Esca de la Vigne. Identification and mode of action of fungi involved in the esca syndrome in the vine [Internet]. PhD thesis, Université de Bordeaux 2. 1991. Available: http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=146151

- 29.Schmidt CS, Wolf GA, Lorenz D. Production of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes by the grapevine dieback fungus Eutypa lata. Z Für Pflanzenkrankh Pflanzenschutz J Plant Dis Prot. 1999;106: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rolshausen PE, Greve LC, Labavitch JM, Mahoney NE, Molyneux RJ, Gubler WD. Pathogenesis of Eutypa lata in grapevine: Identification of virulence factors and biochemical characterization of cordon dieback. Phytopathology. 2008;98: 222–229. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-98-2-0222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valtaud C, Larignon P, Roblin G, Fleurat-Lessard P. Developmental and ultrastructural features of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora and Phaeoacremonium aleophilum in relation to xylem degradation in esca disease of the grapevine. J Plant Pathol. 2009;91: 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchi G, Roberti S, D’Ovidio R, Mugnai L, Surico G. Pectic enzymes production by Phaeomoniella chlamydospora. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2001;40: 407–416. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klosterman SJ, Subbarao KV, Kang S, Veronese P, Gold SE, Thomma BPHJ, et al. Comparative genomics yields insights into niche adaptation of plant vascular wilt pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7: e1002137 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morales-Cruz A, Amrine KCH, Blanco-Ulate B, Lawrence DP, Travadon R, Rolshausen PE, et al. Distinctive expansion of gene families associated with plant cell wall degradation, secondary metabolism, and nutrient uptake in the genomes of grapevine trunk pathogens. BMC Genomics. 2015;16: 469 doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1624-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kissen R, Bones AM. Phytoalexins in defense against pathogens. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17: 73–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erdtman H. Die phenolischen Inhaltsstoffe des Kiefernkernholzes, ihre physiologische Bedeutung und hemmende Einwirkung auf die normale Aufschließbarkeit des Kiefernkernholzes nach dem Sulfitverfahren. Justus Liebigs Ann Chem. 1939;539: 116–127. doi: 10.1002/jlac.19395390111 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeandet P, Douillet-Breuil A-C, Bessis R, Debord S, Sbaghi M, Adrian M. Phytoalexins from the Vitaceae: Biosynthesis, phytoalexin gene expression in transgenic plants, antifungal activity, and metabolism. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50: 2731–2741. doi: 10.1021/jf011429s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chong J, Poutaraud A, Hugueney P. Metabolism and roles of stilbenes in plants. Plant Sci. 2009;177: 143–155. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.05.012 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pawlus AD, Waffo-Téguo P, Shaver J, Mérillon J-M. Stilbenoid chemistry from wine and the genus Vitis, a review. OENO One. 2012;46: 57–111. doi: 10.20870/oeno-one.2012.46.2.1512 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu CKY, Lam CNW, Springob K, Schmidt J, Chu IK, Lo C. Constitutive accumulation of cis-piceid in transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing a sorghum stilbene synthase gene. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47: 1017–1021. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu CKY, Shih C-H, Chu IK, Lo C. Accumulation of trans-piceid in sorghum seedlings infected with Colletotrichum sublineolum. Phytochemistry. 2008;69: 700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pezet R, Gindro K, Viret O, Spring J-L. Glycosylation and oxidative dimerization of resveratrol are respectively associated to sensitivity and resistance of grapevine cultivars to downy mildew. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2004;65: 297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2005.03.002 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidlin L, Poutaraud A, Claudel P, Mestre P, Prado E, Santos-Rosa M, et al. A stress-inducible resveratrol O-methyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of pterostilbene in grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2008;148: 1630–1639. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.126003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amalfitano C, Evidente A, Surico G, Tegli S, Bertelli E, Mugnai L. Phenols and stilbene polyphenols in the wood of esca-diseased grapevines. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2000;39: 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calzarano F, D’Agostino V, Carlo MD. Trans‐resveratrol extraction from grapevine: Application to berries and leaves from vines affected by esca proper. Anal Lett. 2008;41: 649–661. doi: 10.1080/00032710801910585 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin N, Vesentini D, Rego C, Monteiro S, Oliveira H, Ferreira RB. Phaeomoniella chlamydospora infection induces changes in phenolic compounds content in Vitis vinifera. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2009;48: 101–116. doi: 10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-2879 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lima MRM, Felgueiras ML, Graca G, Rodrigues JEA, Barros A, Gil AM, et al. NMR metabolomics of esca disease-affected Vitis vinifera cv. Alvarinho leaves. J Exp Bot. 2010;61: 4033–4042. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Letousey P, Baillieul F, Perrot G, Rabenoelina F, Boulay M, Vaillant-Gaveau N, et al. Early events prior to visual symptoms in the apoplectic form of grapevine esca disease. Phytopathology. 2010;100: 424–431. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-100-5-0424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lambert C, Bisson J, Waffo-Téguo P, Papastamoulis Y, Richard T, Corio-Costet M-F, et al. Phenolics and their antifungal role in grapevine wood decay: Focus on the Botryosphaeriaceae family. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60: 11859–11868. doi: 10.1021/jf303290g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Messerschmidt A, Huber R. The blue oxidases, ascorbate oxidase, laccase and ceruloplasmin modelling and structural relationships. FEBS J. 1990;187: 341–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15311.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pezet R. Purification and characterization of a 32-kDa laccase-like stilbene oxidase produced by Botrytis cinerea Pers.:Fr. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;167: 203–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13229.x [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cichewicz RH, Kouzi SA, Hamann MT. Dimerization of resveratrol by the grapevine pathogen Botrytis cinerea. J Nat Prod. 2000;63: 29–33. doi: 10.1021/np990266n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baldrian P. Wood-inhabiting ligninolytic basidiomycetes in soils: Ecology and constraints for applicability in bioremediation. Fungal Ecol. 2008;1: 4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2008.02.001 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bruno G, Sparapano L. Effects of three esca-associated fungi on Vitis vinifera L.: III. Enzymes produced by the pathogens and their role in fungus-to-plant or in fungus-to-fungus interactions. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2006;69: 182–194. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2007.04.006 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dekker RFH, Vasconcelos A-FD, Barbosa AM, Giese EC, Paccola-Meirelles L. A new role for veratryl alcohol: regulation of synthesis of lignocellulose-degrading enzymes in the ligninolytic ascomyceteous fungus, Botryosphaeria sp.; influence of carbon source. Biotechnol Lett. 2001;23: 1987–1993. doi: 10.1023/A:1013742527550 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Esteves AC, Saraiva M, Correia A, Alves A. Botryosphaeriales fungi produce extracellular enzymes with biotechnological potential. Can J Microbiol. 2014;60: 332–342. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2014-0134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stempien E, Goddard M-L, Leva Y, Bénard-Gellon M, Laloue H, Farine S, et al. Secreted proteins produced by fungi associated with Botryosphaeria dieback trigger distinct defense responses in Vitis vinifera and Vitis rupestris cells. Protoplasma. 2017; 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00709-016-1050-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Larignon P, Fulchic R, Cere L, Dubos B. Observation on black dead arm in French vineyards. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2001;40: 336–342. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eriksson K-E, Pettersson B. Extracellular enzyme system utilized by the fungus Sporotrichum pulverulentum (Chrysosporium lignorum) for the breakdown of cellulose. Eur J Biochem. 1975;51: 193–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb03919.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wood IP, Elliston A, Ryden P, Bancroft I, Roberts IN, Waldron KW. Rapid quantification of reducing sugars in biomass hydrolysates: Improving the speed and precision of the dinitrosalicylic acid assay. Biomass Bioenergy. 2012;44: 117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.05.003 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mathieu Y, Gelhaye E, Dumarçay S, Gérardin P, Harvengt L, Buée M. Selection and validation of enzymatic activities as functional markers in wood biotechnology and fungal ecology. J Microbiol Methods. 2013;92: 157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li C, Lu J, Xu X, Hu R, Pan Y. pH-switched HRP-catalyzed dimerization of resveratrol: A selective biomimetic synthesis. Green Chem. 2012;14: 3281–3284. doi: 10.1039/C2GC36288K [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mora‐Pale M, Bhan N, Masuko S, James P, Wood J, McCallum S, et al. Antimicrobial mechanism of resveratrol‐trans‐dihydrodimer produced from peroxidase‐catalyzed oxidation of resveratrol. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112: 2417–2428. doi: 10.1002/bit.25686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9: 671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Internet]. Vienna, Austria; 2016. Available: https://www.R-project.org

- 66.Djoukeng JD, Polli S, Larignon P, Abou-Mansour E. Identification of phytotoxins from Botryosphaeria obtusa, a pathogen of black dead arm disease of grapevine. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2009;124: 303–308. doi: 10.1007/s10658-008-9419-6 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blanchette RA. Degradation of the lignocellulose complex in wood. Can J Bot. 1995;73: 999–1010. doi: 10.1139/b95-350 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jodin P, Militon J. Le bois matériau d’ingénierie. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Úrbez-Torres JR, Leavitt GM, Guerrero JC, Guevara J, Gubler WD. Identification and pathogenicity of Lasiodiplodia theobromae and Diplodia seriata, the causal agents of bot canker disease of grapevines in Mexico. Plant Dis. 2008;92: 519–529. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-92-4-0519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pitt WM, Huang R, Steel CC, Savocchia S. Pathogenicity and epidemiology of Botryosphaeriaceae species isolated from grapevines in Australia. Australas Plant Pathol. 2013;42: 573–582. doi: 10.1007/s13313-013-0221-3 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen SF, Morgan DP, Michailides TJ. Botryosphaeriaceae and Diaporthaceae associated with panicle and shoot blight of pistachio in California, USA. Fungal Divers. 2014;67: 157–179. doi: 10.1007/s13225-014-0285-6 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guan X, Essakhi S, Laloue H, Nick P, Bertsch C, Chong J. Mining new resources for grape resistance against Botryosphaeriaceae: A focus on Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris. Plant Pathol. 2016;65: 273–284. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12405 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lardner R, Mahoney N, Zanker TP, Molyneux RJ, Scott ES. Secondary metabolite production by the fungal pathogen Eutypa lata: Analysis of extracts from grapevine cultures and detection of those metabolites in planta. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2006;12: 107–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0238.2006.tb00049.x [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abou-Mansour E, Polier J, Pezet R, Tabacchi R. Purification and partial characterisation of a 60 KDa laccase from Fomitiporia mediterranea. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2010;48: 447–453. doi: 10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-2771 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Langcake P, Pryce RJ. The production of resveratrol and the viniferins by grapevines in response to ultraviolet irradiation. Phytochemistry. 1977;16: 1193–1196. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)94358-9 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pezet R, Pont V. Mise en évidence de ptérostilbène dans les grappes de Vitis vinifera. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1988;26: 603–607. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pezet R, Perret C, Jean-Denis JB, Tabacchi R, Gindro K, Viret O. δ-Viniferin, a resveratrol dehydrodimer: One of the major stilbenes synthesized by stressed grapevine leaves. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51: 5488–5492. doi: 10.1021/jf030227o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chalal M, Klinguer A, Echairi A, Meunier P, Vervandier-Fasseur D, Adrian M. Antimicrobial activity of resveratrol analogues. Molecules. 2014;19: 7679–7688. doi: 10.3390/molecules19067679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mazzullo A, Cesari A, Osti F, Di Marco S. Bioassays on the activity of resveratrol, pterostilbene and phosphorous acid towards fungi associated with esca of grapevine. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2000;39: 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beneventi E, Conte S, Cramarossa MR, Riva S, Forti L. Chemo-enzymatic synthesis of new resveratrol-related dimers containing the benzo[b]furan framework and evaluation of their radical scavenger activities. Tetrahedron. 2015;71: 3052–3058. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2014.11.012 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table A: Data for polysaccharide degrading enzyme activities (Fig 1). Table B: Data for laccase and peroxidase activities (Fig 2). Table C: data of fungi growth in media containing viniferin (Fig 3). Table D: data of fungi growth in medium containing resveratrol (Fig 4). Table E: data of fungi growth in media containing δ-viniferin or resveratrol, one day before Petri dish saturation (Fig 5). Table F: data of resveratrol metabolization (Fig 6). Table G: data of δ-viniferin metabolization (Fig 7).

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.