Abstract

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common adult leukemia. Only a fraction of AML patients will survive with existing chemotherapy regimens. Hence, there is an urgent and unmet need to identify novel targets and develop better therapeutics in AML. In the past decade, the field of sphingolipid metabolism has emerged into the forefront of cancer biology due to its importance in cancer cell proliferation and survival. In particular, acid ceramidase (AC) has emerged as a promising therapeutic target due to its role in neutralizing the pro-death effects of ceramide.

Areas covered

This review highlights key information about AML biology as well as current knowledge on dysregulated sphingolipid metabolism in cancer and AML. We describe AC function and dysregulation in cancer, followed by a review of studies that report elevated AC in AML and compounds known to inhibit the enzyme.

Expert opinion

AML has a great need for new drug targets and better therapeutic agents. The finding of elevated AC in AML supports the concept that this enzyme represents a novel and realistic therapeutic target for this common leukemia. More effort is needed towards developing better AC inhibitors for clinical use and combination treatment with existing AML therapies.

Keywords: acid ceramidase, ceramide, sphingosine 1-phosphate, acute myeloid leukemia

1. Background and introduction

1.1. Acute myeloid leukemia

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a malignancy of the blood and bone marrow characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of immature cells of the myeloid lineage. These cells, called blasts, overpopulate the blood as well as bone marrow and compromise production of normal blood cells. As a result, patients may present with symptoms of anemia, bleeding or infection. As an acute disease, AML exhibits sudden onset and rapid progression. Only 27% of patients survive five years past diagnosis1. Prognosis is even worse for some groups, including those above the age of 65 and those whose disease has developed from myelodysplastic syndrome or following prior chemotherapy2-4.

In addition to the challenge of a quickly progressing disease, AML is also extremely heterogeneous in terms of clinical behavior and genetic alterations5-8. Although the most common mutations in AML are only present in about 30% of adult cases 9, patient classification based on mutation profile is a powerful prognostic indicator6-8. A comprehensive genomic profiling tool was recently developed to identify somatic alterations that affect diagnosis, prognosis and treatment10. However, genetic heterogeneity means that therapeutic agents to selectively target specific mutations are of limited benefit to most AML patients. Thus, there is also a need to identify non-genetic biochemical commonalities among patients in order to optimize treatment for widespread therapeutic benefit.

1.2. Current Treatments for AML

Sadly, treatment for AML patients has not changed much since the 1970s, despite the wealth of knowledge accumulated since then 11, 12. Standard chemotherapy for patients, the “7+3” combination of cytarabine and daunorubicin infusion, can induce complete remission in approximately 80% of patients under 60 years of age 13. Patients above 60 years of age have much lower response rates to standard chemotherapy. If remission is achieved with induction chemotherapy, then consolidation therapy to prevent relapse is administered. Consolidation therapy could consist of additional rounds of high dose chemotherapy or consideration of autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant. There is debate as to when best to recommend transplant, but high risk patients are often considered for stem cell transplantation in first remission14, 15. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) provides benefit of the graft versus leukemia effect but increases the risk of graft versus host disease and other complications11, 14-16.

Unfortunately these approaches are not curative in most patients, and there has been great interest in developing new AML therapeutic targets and strategies. Particularly encouraging is the introduction of mutational profiling of AML samples and the increase in small molecule inhibitors to selectively target these molecular alterations or other aberrations in AML 17-19. Many other approaches are underway as well. DNA hypomethylating agents such as azacitidine and decitabine can increase survival in a fraction of older AML patients, but these agents are still being tested in clinical trials and are currently not FDA-approved for the treatment of AML 20. Other agents such as CPX-351 and SGN-CD33A are next-generation formulations of existing chemotherapy and antibody-drug conjugates, respectively, that may prove beneficial for AML patients 21.

1.3. Sphingolipid and ceramide metabolism

Sphingolipid metabolism is an up and coming topic in the field of cancer biology, particularly for difficult to treat diseases like AML. Sphingolipids are essential for formation of the plasma membrane and to maintain structural integrity of the cell. However, sphingolipid metabolism also produces bioactive signaling molecules that regulate critical processes like cell survival and differentiation 22-24. Although sphingolipid metabolism and inter-conversion is complex, ceramide, sphingosine and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) are the bioactive core.

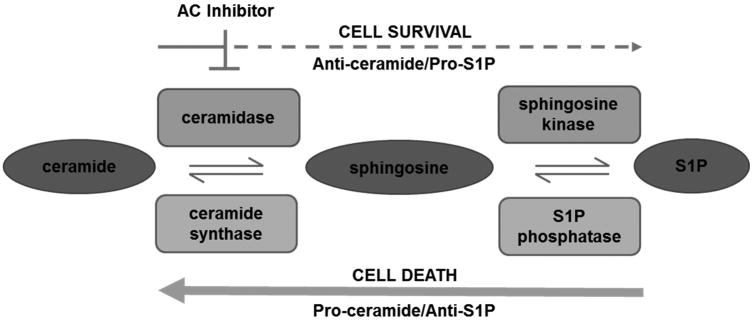

Ceramides are a class of sphingolipids that contain a sphingoid base and a fatty acid. These molecules are synthesized several different ways. De novo synthesis is initiated by condensation of serine and palmitoyl-CoA. Other precursors include glycosphingolipids, sphingomyelin and phosphorylated metabolites like ceramide 1-phosphate and sphingosine 1-phosphate22-24. The ceramide-S1P flux is most widely studied for its implication in many diseases, including cancer (Figure 1). In the first step of this process, the fatty acid of ceramide is cleaved by a ceramidase to produce sphingosine, which is subsequently phosphorylated by sphingosine kinase to produce S1P. This reversible process is key in regulating cell survival and death25. Dysregulation of these metabolites contributes to the progression of several diseases including multiple cancers 22, 26.

Figure 1. Ceramidase inhibitors reverse the dysregulated sphingolipid rheostat and induce cell death in AML.

The sphingolipid rheostat is imbalanced in AML, with S1P production dominating to produce a pro-survival phenotype. Of the five ceramidases, the mRNA content and enzymatic activity of acid ceramidase (AC) are selectively upregulated in AML. Upon AC inhibition, ceramide accumulates to induce cell death, which reveals a promising therapeutic target for AML.

Ceramide accumulation induces apoptosis and other cell death mechanisms while formation of S1P promotes cell survival 22. In healthy cells, the ratio of ceramide to S1P is relatively stable so that pro-survival and pro-death signals are balanced. However, if this balance is disrupted, cells normally destined for death can proliferate and lead to disease. This balance is tightly regulated by the enzymes involved in formation and breakdown of ceramide. When pro-death signals are prominent, ceramide accumulates via the action of S1P phosphatases that generate sphingosine and ceramide synthases that then produce ceramide. Pro-survival signals dominate in cancer with increased formation of sphingosine and pro-survival S1P through ceramidases and sphingosine kinases, respectively. Exploiting this imbalance in complex diseases like AML provides a unique and promising opportunity to discover essential biochemical dependencies that represent novel therapeutic targets.

1.4. Sphingolipids and AML

In AML, patient cells generally exhibit upregulation of enzymes that degrade ceramide and synthesize S1P27, 28. This suggests a dependence on this pathway for AML blast survival, thus multiple therapeutic approaches to manipulate ceramide levels are at the forefront of current sphingolipid research in AML. For example, treatment of AML cells with sphingosine analog FTY720 rapidly induces ceramide-mediated apoptosis29. The synthetic retinoid fenretinide was shown to induce up to 20-fold increase in ceramide in AML cell lines, yielding cytotoxic effects 30. It has also been shown that treatment with ceramide analog LCL-461 leads to death of AML cells, including those that are drug resistant 31. Multiple studies investigate the use of exogenous short chain ceramides as potential therapeutics for cancer, especially in combination with other drugs 32. Combination treatment with C6-ceramide and tamoxifen induces alternations in energy production and decreases expression of anti-apoptotic proteins in AML cells33-35. Blocking intracellular ceramide modifications as well as treating with exogenous ceramide using nanoliposomes both induced apoptosis in AML 36. S1P-generating enzymes are also important in AML. Inhibition of sphingosine kinase 1 by SKI-I and SKI-178 induces AML cell apoptosis, highlighting the importance of S1P formation in AML cell survival 28, 37, 38.Aberrant signaling induced by the FLT3-ITD mutation represses the production of pro-death ceramide 31, thus demonstrating that common molecular alterations in AML may drive sphingolipid dysregulation.

2. Acid ceramidase (AC)

2.1. Ceramidase genes and cancer

There are five ceramidase genes that encode for a family of enzymes whose optimal enzymatic activity is dependent upon pH, which includes acid ceramidase (ASAH1, referred to in this review as AC), neutral ceramidase (ASAH2) and three alkaline ceramidases (ACER1, 2 and 3). AC is synthesized as an inactive precursor that is auto-cleaved to form the α and β subunits of the mature enzyme 39. AC dominates the literature as a therapeutic target, while other ceramidases have not been as extensively studied in this context40, 41. AC is upregulated in multiple cancers including prostate, melanoma and head and neck cancers 42, and increased AC leads to proliferation and increased growth rate of oncogenic cells 43. Multiple studies have shown that blocking AC activity induces ceramide accumulation and leads to cell death. These studies suggest that AC inhibition may be a broadly effective strategy for cancers that exhibit sphingolipid dysregulation, particularly those with AC upregulation (Figure 1).

Several publications have shown that elevated AC contributes to cancer progression and demonstrated that targeting AC results in marked improvement in pre-clinical in vitro and in vivo models for solid cancers 43-46, but few studies have focused on hematological malignancies. Hu et al. demonstrated that indirect targeting, through restoration of the AC repressor IRF-8, decreased AC expression and sensitized chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells to Fas ligand-induced apoptosis 47. Based on the these studies, AC activity represents a valid target for future AML therapy and supporting evidence is described in the following sections.

2.2. AC as a novel target in AML

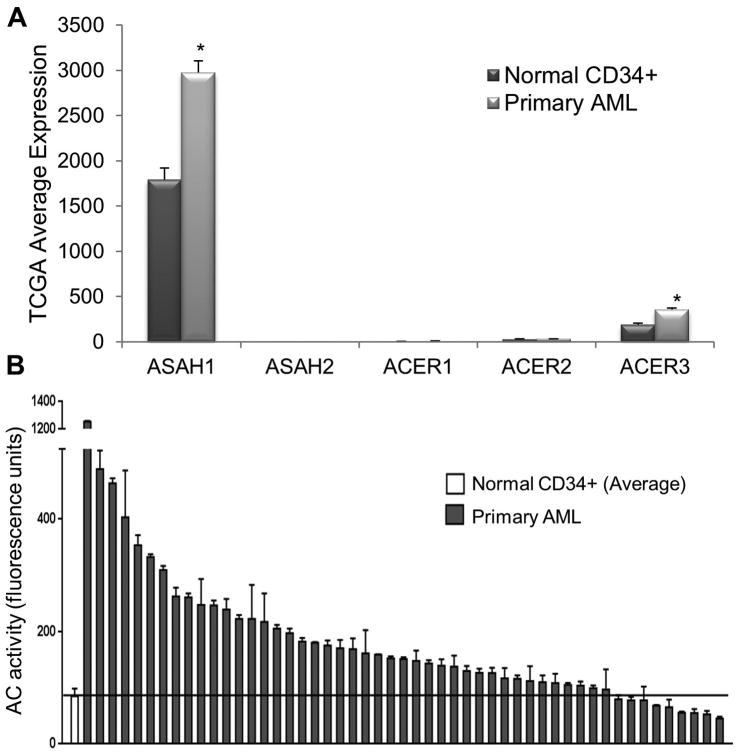

Recent work by the Loughran group utilized primary patient samples, cell lines and in vivo murine models to demonstrate AC overexpression and therapeutic potential in AML 27. Based on RNA-Seq data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network, gene expression microarray and AC enzymatic activity screening, AML patient samples exhibit upregulated AC expression and activity relative to normal controls (Figure 2A)27. Interestingly, there was no conclusive evidence that other ceramidases have significant expression or upregulation in the same AML cohorts, with AC expression being at least 10-fold higher than all other ceramidases (Figure 2A). This is a pattern that is currently unique to AML and highlights the importance and specificity of this AC increase. In the TCGA data, average AC expression in 145 AML patient samples was 1.7 times higher than in normal bone marrow cells, while the average AC activity in a separate cohort of 51 AML patient samples was 2.3 times higher than in normal CD34+ controls (Figure 2B). This upregulation explains at least one mechanism for AML cells to enhance their survival by diverting endogenous ceramide towards the production of S1P, which is enabled by the excess sphingosine produced by AC upregulation. S1P, in turn, modulates survival through various mechanisms including receptor dependent or independent signaling pathways 48, 49. Thus, AC is positioned at the fulcrum of the “sphingosine rheostat” between the ceramide and S1P arms where it can play a pivotal role in cell death vs. cell survival determination50. Ceramide and S1P can also exert opposite effects on Bcl-2 family members. Multiple groups have shown that ceramide decreases Mcl-1 expression and S1P promotes Mcl-1 expression 27, 51-54. Hence, AC's role in cancer cell survival extends beyond modulating ceramide/S1P level and into regulating the expression of Bcl-2 family members.

Figure 2. AC expression and activity are elevated in AML.

(A) TCGA RNA-Seq gene expression data in 145 AML patients and 5 normal BM samples for ceramidases ASAH1 (acid ceramidase), ASAH2 (neutral ceramidase), ACER1 (alkaline ceramidase 1), ACER2 (alkaline ceramidase 2) and ACER3 (alkaline ceramidase 3). Each bar represents mean and error bars represent standard error of mean (SEM).*, p<0.05, indicates significant difference of AML patient cells compared to normal CD34+ cells (Wald test and Benjamini-Hochberg procedure). (B) AC activity of normal CD34+ cells (n=12, far left, mean ± SEM) and primary AML patient samples (n=51). AC activity is elevated in the vast majority of AML patient cells compared to normal controls (p=0.0016; Wilcoxon rank sum test). Solid line represents the normal mean. Figure reproduced with permission from Tan et al., Oncotarget, 2016.

2.3. Therapeutic potential of AC inhibitors in AML

In the cohort of AML patient samples tested, high AC activity significantly correlated with reduced overall survival and reduced relapse-free survival relative to samples with low AC activity (Figure 3)27. Ongoing studies aim to validate this finding in a larger independent cohort. This correlation suggests that AC activity is clinically relevant, and multiple in vitro and in vivo models were utilized to provide additional evidence that AC is an excellent therapeutic target for AML 27. These studies utilized AC inhibitor LCL204, which has been used previously in prostate cancer and head and neck squamous cancer models 55, 56, and these findings were validated through shRNA-mediated genetic targeting of AC. LCL204 treatment reduced viability and increased apoptosis in AML cell lines and primary patient samples. Pharmacologic and genetic targeting of AC also resulted in decreased Mcl-1 content. Mcl-1 is an interesting target for multiple cancers due to its ability to bind Bak and prevent mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization 57-60. Casson et al. showed that combining Bcl-2 family inhibitors with drugs targeting ceramide metabolism effectively killed leukemic cell lines 61. Hence, targeting AC in AML may have a two-pronged effect through reversal of ceramide/S1P dysregulation and induction of cell death by decreasing Mcl-1 expression. Furthermore, elevated AC expression is selectively found in patient samples, thus the cancerous AML blasts are more sensitive to AC inhibition than normal counterparts27. The therapeutic effect of AC inhibition with LCL-204 was also demonstrated through reduced tumor burden in patient-derived xenotransplanted NSG mice and increased survival in a murine AML model 27. Overall, these studies validate AC as a novel target in AML that could be of great therapeutic benefit, and more AC inhibitors should be tested and studied for clinical use in AML therapy.

Figure 3. High AC activity correlated with lower overall survival and lower relapse-free survival in AML patients.

AC activity values were dichotomized into high/low categories according to whether they were larger than the mean. Patients were filtered to include only those that received standard chemotherapy “7+3”. The main clinical outcomes used were (A) overall survival (OS) and (B) relapse-free survival (RFS). Kaplan-Meier plots and log-rank tests were used to examine the correlation between AC level and OS/RFS. The analysis of RFS was only done for patients who had complete remission (CR) or complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) after primary therapy. Figure reproduced with permission from Tan et al., Oncotarget, 2016.

3. AC inhibitors

3.1. Development and characterization of AC inhibitors

Multiple small molecule AC inhibitors have been developed and are currently being utilized for preclinical studies, however none of these agents have advanced to clinical trials in cancer patients. Methods to improve the synthesis and characterization of AC inhibitors continue to evolve and will facilitate the identification of more efficient compounds 62, 63. Additionally, development of a fluorogenic AC substrate to measure enzyme activity facilitates the identification and characterization of these inhibitors 64, 65. Importantly, a conditional AC knockout mouse has been developed that may be useful to further validate AC as a target in particular cancer types 66. This review will focus on new agents since previous reviews detail several of these compounds including ceranibs, derivatives of N-oleoylethanolamide (NOE), and multiple AC-targeting drugs of the LCL series of B13 analogs67-71.

The LCL series is composed of N-dimethylglycine (DMG)-B13 prodrugs that are metabolized to B13, a known inhibitor of ceramidases. These novel drugs target the lysosome for acid ceramidase specificity. LCL521 was shown to be the most active toward AC and to prevent relapse of prostate cancer in mice 72. LCL521 also improved the efficacy of photodynamic therapy in head and neck cancer 73. As described above, ceramide analog LCL204 was shown to decrease AC activity and induce ceramide-mediated apoptosis of AML cell lines and patient samples as well as significantly extend the life of AML engrafted mice 27. This demonstration of pronounced in vivo therapeutic efficacy is particularly important to advance inhibitors towards clinical trials. Another group developed a set of thiol reactive ceramide analogs to inhibit the cysteine hydrolase activity of AC. Two of these compounds, SABRAC and RBM1-12, induced ceramide accumulation followed by cell death in metastatic prostate cancer cells 64. Another recent AC inhibitor was suggested as a potent treatment for stage II melanoma. ARN14899 decreased AC activity with an IC50 of 12nM and induced ceramide accumulation. Alone, the compound was only mildly toxic at micromolar concentrations, but viability of proliferative melanoma cells was drastically reduced when combined with chemotherapeutics45. Benzoxazolone carboxamide prototypes have also been studied as potent acid ceramidase inhibitors74, 75. Additionally, small peptide targeting of AC with cystatin SA lead to reduced AC activity and increased ceramide accumulation 76. This highlights an alternative mechanistic approach to modulate AC activity by targeting the autocatalytic cleavage event that is required to generate the mature active enzyme.

3.2. Clinically used compounds that target AC

Although many studies have shown the potential of therapeutics designed to specifically target AC, identifying FDA-approved agents with AC inhibitory activity is an alternative approach that may have great clinical importance. It was recently discovered that tamoxifen, a commonly used chemotherapeutic and chemopreventive agent, alters sphingolipid metabolism. Both tamoxifen and its metabolite N-desmethyltamoxifen specifically reduce ceramide glycosylation and inhibit acid ceramidase independent of known anti-estrogen mechanisms. Co-treatment with tamoxifen and exogenous ceramide or a ceramide-generating drug induced synergistic apoptosis in AML cells77.

Dacarbazine is another approved chemotherapeutic drug with inhibitory activity against AC. Used in the treatment of melanoma, Bedia, C. et al. showed that dacarbazine activates cathepsin B-mediated degradation of AC expression in A375 melanoma cells78. Carmofur, a derivative of 5-fluorouracil, was also reported to be an inhibitor of acid ceramidase that worked at nanomolar concentrations79. The compound is clinically approved in China and has been shown to strongly inhibit acid ceramidase activity, leading to increased in vivo sensitivity to chemotherapeutics in colorectal cancer80. Meta-analysis of three international clinical trials showed modest but significant survival increase in patients treated with carmofur after tumor resection81. These drugs provide promising opportunities to target AC with more expedited bench-to-patient timelines.

4. Conclusion

The information presented and discussed here shows that dysregulated sphingolipids promote cancer cell survival. AC expression is elevated in AML, which enhances the catabolism of ceramide and promotes the production of S1P. AC inhibition in AML patient samples, cell lines and animal models reduced cell viability and induced leukemic cell death. Hence, AC represents a promising drug target for future development of effective AML therapeutics.

5. Expert opinion

Overall, a growing body of work in cell lines, animal models and primary patient samples strongly supports AC as an essential biochemical activity and promising therapeutic target in AML. Further studies are needed to address open questions and facilitate the leap from bench to bedside. First, there is a need to continue to develop new inhibitory compounds and characterize existing agents. Although many AC inhibitors have been reported, none are approved for clinical use due to various limitations. Such agents will need to have optimal potency, specificity, toxicity and pharmacological characteristics to enable the field to transition from preclinical target validation with tool compounds and genetic knockdown to clinical trials in AML patients.

Second, there is a need to explore differential AC expression and AC inhibitor sensitivity at disease relapse and across the heterogeneous AML subgroups in order to identify the patient population(s) most likely to benefit from these agents. Thus far there is convincing evidence of AC upregulation in the vast majority of AML samples, and further analyses in large independent cohorts are needed to firmly establish the link between AC activity and patient prognosis. Such data could establish AC activity as a prognostic biomarker to identify patients that need more aggressive therapeutic approaches. Additional data and mechanistic studies are required to investigate whether the mutational profile is linked to AC activity and to determine the universality of sensitivity to AC targeting agents. Another aspect of AC upregulation in need of further investigation is within the hierarchy of leukemic stem cells and whether AC confers a survival advantage in these populations. Few studies have addressed primary and secondary resistance mechanisms that may thwart AC targeting agents, which will become important as inhibitors advance to clinical trials in AML and other cancers. All of these efforts would benefit from increased development and application of cell line and murine models engineered to manipulate AC expression and to recapitulate specific genetic alterations that represent AML subgroups. Similar efforts are also required for other sphingolipid metabolic enzymes and ceramide detoxification pathways, such as ceramide synthases, sphingosine kinases and glucosylceramide synthases in order to move the field forward.31, 35

Finally, targeting AC can modulate cellular sphingolipid profiles and impact multiple survival and death pathways. There are multiple reports of sphingolipids' downstream influence on several of the Bcl-2 family of survival proteins, which are also promising targets for therapeutic development27, 51-54, 61. We propose that AC inhibitors may therefore have broader activity than agents that target a single Bcl-2 family protein. Future studies are needed to compare these therapeutic approaches alone and in combination. Additional studies of AC inhibitors are also needed in combination with existing AML therapies and new agents that target molecular alterations in the disease to determine the most promising regimens to advance to clinical trials 10, 11, 13. AC inhibitors may also prove more effective when combined with other sphingolipid modulators such as inhibitors of sphingosine kinases and glucosylceramide synthase, S1P receptor antagonists or exogenous short-chain ceramide nanoliposomes 28, 33, 52. Together these studies will enable the continued advancement of AC inhibits towards clinical usage in a disease that desperately needs more precise and rational therapeutic approaches.

Article Highlights.

Novel therapeutics for AML are greatly needed due to lack of treatment advances

Sphingolipid metabolism is dysregulated in AML and contributes to blast survival

Acid ceramidase is upregulated in AML and elevated activity correlates with reduced patient survival

Acid ceramidase inhibitors exhibit preclinical efficacy against AML in vitro and in vivo

Optimized acid ceramidase inhibitors are needed for advancement to clinical trials

Acknowledgments

We apologize to any investigators whose important work was not included due to space limitations. The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaborative support and discussions of all members of the projects and cores within our funded Program Project (P01) “Targeted Sphingolipid Metabolism for Treatment of AML”. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding: The authors are supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, under award number P01CA171983 to T. P. Loughran and NIH training grant T32-GM007055 to J. M. Pearson.

This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Abbreviations

- AC

acid ceramidase

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- S1P

sphingosine 1-phosphate

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2013. National Cancer Institute; Apr, 2016. cited; Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klepin HD, Balducci L. Acute myelogenous leukemia in older adults. Oncologist. 2009 Mar;14:222–32. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okuyama N, Sperr WR, Kadar K, et al. Prognosis of acute myeloid leukemia transformed from myelodysplastic syndromes: a multicenter retrospective study. Leuk Res. 2013 Aug;37:862–7. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leone G, Voso MT, Sica S, et al. Therapy related leukemias: susceptibility, prevention and treatment. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001 Apr;41:255–76. doi: 10.3109/10428190109057981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5•.Papaemmanuil E, Dohner H, Campbell PJ. Genomic Classification in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 01;375:900–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1608739. See Reference 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013 May 30;368:2059–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. See Reference 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7•.Grimwade D, Ivey A, Huntly BJ. Molecular landscape of acute myeloid leukemia in younger adults and its clinical relevance. Blood. 2016 Jan 07;127:29–41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-604496. See Reference 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Metzeler KH, Herold T, Rothenberg-Thurley M, et al. Spectrum and prognostic relevance of driver gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2016 Aug 04;128:686–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-693879. These publications detailed molecular alterations in AML and redefined the conventional AML subtypes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatzimichael E, Georgiou G, Benetatos L, et al. Gene mutations and molecularly targeted therapies in acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Blood Res. 2013;3:29–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He J, Abdel-Wahab O, Nahas MK, et al. Integrated genomic DNA/RNA profiling of hematologic malignancies in the clinical setting. Blood. 2016 Jun 16;127:3004–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-664649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Coombs CC, Tallman MS, Levine RL. Molecular therapy for acute myeloid leukaemia. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016 May;13:305–18. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.210. See Reference 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017 Jan 26;129:424–47. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dombret H, Gardin C. An update of current treatments for adult acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2016 Jan 07;127:53–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-604520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanada M, Kurosawa S, Kobayashi T, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a registry-based study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017 Jan 23; doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisdorf DJ, Millard HR, Horowitz MM, et al. Allogeneic transplantation for advanced acute myeloid leukemia: The value of complete remission. Cancer. 2017 Jan 24; doi: 10.1002/cncr.30536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballen KK. Is there a best graft source of transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia? Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2015 Jun-Sep;28:147–54. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan I, Altman JK, Licht JD. New strategies in acute myeloid leukemia: redefining prognostic markers to guide therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012 Oct 01;18:5163–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel JP, Gonen M, Figueroa ME, et al. Prognostic relevance of integrated genetic profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2012 Mar 22;366:1079–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dawson MA, Kouzarides T, Huntly BJ. Targeting epigenetic readers in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 16;367:647–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1112635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cashen AF, Schiller GJ, O'Donnell MR, et al. Multicenter, phase II study of decitabine for the first-line treatment of older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Feb 01;28:556–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21•.Stein EM, Tallman MS. Emerging therapeutic drugs for AML. Blood. 2016 Jan 07;127:71–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-604538. These publications are good reviews on the latest therapy development in AML and the link to molecular alterations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Ryland LK, Fox TE, Liu X, et al. Dysregulation of sphingolipid metabolism in cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011 Jan 15;11:138–49. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.2.14624. See Reference 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haimovitz-Friedman A, Kolesnick RN, Fuks Z. Ceramide signaling in apoptosis. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:539–53. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24•.Spiegel S, Foster D, Kolesnick R. Signal transduction through lipid second messengers. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996 Apr;8:159–67. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80061-5. See Reference 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao C, Obeid LM. Ceramidases: regulators of cellular responses mediated by ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008 Sep;1781:424–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26•.Morad SA, Cabot MC. Ceramide-orchestrated signalling in cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013 Jan;13:51–65. doi: 10.1038/nrc3398. •These publications provide background knowledge on sphingolipid characterization and functions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27••.Tan SF, Liu X, Fox TE, et al. Acid ceramidase is upregulated in AML and represents a novel therapeutic target. Oncotarget. 2016 Dec 13;7:83208–22. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13079. Recent publication detailing that AC is elevated in AML and how elevated AC promotes survival in AML. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dick TE, Hengst JA, Fox TE, et al. The apoptotic mechanism of action of the sphingosine kinase 1 selective inhibitor SKI-178 in human acute myeloid leukemia cell lines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015 Mar;352:494–508. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.219659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen L, Luo LF, Lu J, et al. FTY720 induces apoptosis of M2 subtype acute myeloid leukemia cells by targeting sphingolipid metabolism and increasing endogenous ceramide levels. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morad SA, Davis TS, Kester M, et al. Dynamics of ceramide generation and metabolism in response to fenretinide--Diversity within and among leukemia. Leuk Res. 2015 Oct;39:1071–8. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31••.Dany M, Gencer S, Nganga R, et al. Targeting FLT3-ITD signaling mediates ceramide-dependent mitophagy and attenuates drug resistance in AML. Blood. 2016 Oct 13;128:1944–58. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-04-708750. First publication to show link between common AML mutation FLT3-ITD and sphingolipids. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chapman JV, Gouaze-Andersson V, Messner MC, et al. Metabolism of short-chain ceramide by human cancer cells--implications for therapeutic approaches. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010 Aug 01;80:308–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33••.Morad SA, Ryan TE, Neufer PD, et al. Ceramide-tamoxifen regimen targets bioenergetic elements in acute myelogenous leukemia. J Lipid Res. 2016 Jul;57:1231–42. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M067389. Combination of C6-ceramide and tamoxifen treatment induced cell death through ROS generation in AML. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morad SA, Davis TS, MacDougall MR, et al. Role of P-glycoprotein inhibitors in ceramide-based therapeutics for treatment of cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017 Feb 08; doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morad SA, Cabot MC. Tamoxifen regulation of sphingolipid metabolism--Therapeutic implications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015 Sep;1851:1134–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timothy J Brown, Garcia AM, Kissinger LN, et al. Therapeutic Combination of Nanoliposomal Safingol and Nanoliposomal Ceramide for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Leuk. 2013;1:110. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paugh SW, Paugh BS, Rahmani M, et al. A selective sphingosine kinase 1 inhibitor integrates multiple molecular therapeutic targets in human leukemia. Blood. 2008 Aug 15;112:1382–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hengst JA, Wang X, Sk UH, et al. Development of a sphingosine kinase 1 specific small-molecule inhibitor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010 Dec 15;20:7498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shtraizent N, Eliyahu E, Park JH, et al. Autoproteolytic cleavage and activation of human acid ceramidase. J Biol Chem. 2008 Apr 25;283:11253–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709166200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40•.Frohbergh M, He X, Schuchman EH. The molecular medicine of acid ceramidase. Biol Chem. 2015 Jun;396:759–65. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0290. This publication provides an overall review on AC characterization and its role in diseases. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41••.Raisova M, Goltz G, Bektas M, et al. Bcl-2 overexpression prevents apoptosis induced by ceramidase inhibitors in malignant melanoma and HaCaT keratinocytes. FEBS Lett. 2002 Apr 10;516:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02472-9. First known publication to identify acid ceramidase as a potential therapeutic target. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Musumarra G, Barresi V, Condorelli DF, et al. A bioinformatic approach to the identification of candidate genes for the development of new cancer diagnostics. Biol Chem. 2003 Feb;384:321–7. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeidan YH, Jenkins RW, Korman JB, et al. Molecular targeting of acid ceramidase: implications to cancer therapy. Curr Drug Targets. 2008 Aug;9:653–61. doi: 10.2174/138945008785132358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X, Cheng JC, Turner LS, et al. Acid ceramidase upregulation in prostate cancer: role in tumor development and implications for therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009 Dec;13:1449–58. doi: 10.1517/14728220903357512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Realini N, Palese F, Pizzirani D, et al. Acid Ceramidase in Melanoma: EXPRESSION, LOCALIZATION, AND EFFECTS OF PHARMACOLOGICAL INHIBITION. J Biol Chem. 2016 Jan 29;291:2422–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.666909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morad SA, Levin JC, Tan SF, et al. Novel off-target effect of tamoxifen--inhibition of acid ceramidase activity in cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 Dec;1831:1657–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu X, Yang D, Zimmerman M, et al. IRF8 regulates acid ceramidase expression to mediate apoptosis and suppresses myelogeneous leukemia. Cancer Res. 2011 Apr 15;71:2882–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evangelisti C, Evangelisti C, Buontempo F, et al. Therapeutic potential of targeting sphingosine kinases and sphingosine 1-phosphate in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2016 Nov;30:2142–51. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alvarez SE, Harikumar KB, Hait NC, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate is a missing cofactor for the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF2. Nature. 2010 Jun 24;465:1084–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newton J, Lima S, Maceyka M, et al. Revisiting the sphingolipid rheostat: Evolving concepts in cancer therapy. Exp Cell Res. 2015 May 01;333:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li QF, Wu CT, Guo Q, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces Mcl-1 upregulation and protects multiple myeloma cells against apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008 Jun 20;371:159–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watters RJ, Fox TE, Tan SF, et al. Targeting glucosylceramide synthase synergizes with C6-ceramide nanoliposomes to induce apoptosis in natural killer cell leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013 Jun;54:1288–96. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.752485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nica AF, Tsao CC, Watt JC, et al. Ceramide promotes apoptosis in chronic myelogenous leukemia-derived K562 cells by a mechanism involving caspase-8 and JNK. Cell Cycle. 2008 Nov 01;7:3362–70. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.21.6894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coe GL, Redd PS, Paschall AV, et al. Ceramide mediates FasL-induced caspase 8 activation in colon carcinoma cells to enhance FasL-induced cytotoxicity by tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Sci Rep. 2016 Aug 04;6:30816. doi: 10.1038/srep30816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holman DH, Turner LS, El-Zawahry A, et al. Lysosomotropic acid ceramidase inhibitor induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008 Feb;61:231–42. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elojeimy S, Liu X, McKillop JC, et al. Role of acid ceramidase in resistance to FasL: therapeutic approaches based on acid ceramidase inhibitors and FasL gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2007 Jul;15:1259–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chipuk JE, Bouchier-Hayes L, Green DR. Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization during apoptosis: the innocent bystander scenario. Cell Death Differ. 2006 Aug;13:1396–402. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leverson JD, Zhang H, Chen J, et al. Potent and selective small-molecule MCL-1 inhibitors demonstrate on-target cancer cell killing activity as single agents and in combination with ABT-263 (navitoclax) Cell Death Dis. 2015 Jan 15;6:e1590. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gores GJ, Kaufmann SH. Selectively targeting Mcl-1 for the treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia and solid tumors. Genes Dev. 2012 Feb 15;26:305–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.186189.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doi K, Liu Q, Gowda K, et al. Maritoclax induces apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia cells with elevated Mcl-1 expression. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014 Aug;15:1077–86. doi: 10.4161/cbt.29186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Casson L, Howell L, Mathews LA, et al. Inhibition of ceramide metabolism sensitizes human leukemia cells to inhibition of BCL2-like proteins. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bedia C, Casas J, Garcia V, et al. Synthesis of a novel ceramide analogue and its use in a high-throughput fluorogenic assay for ceramidases. Chembiochem. 2007 Apr 16;8:642–8. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xia Z, Draper JM, Smith CD. Improved synthesis of a fluorogenic ceramidase substrate. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010 Feb;18:1003–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.12.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64•.Camacho L, Meca-Cortes O, Abad JL, et al. Acid ceramidase as a therapeutic target in metastatic prostate cancer. J Lipid Res. 2013 May;54:1207–20. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M032375. See Reference 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65•.Bedia C, Camacho L, Abad JL, et al. A simple fluorogenic method for determination of acid ceramidase activity and diagnosis of Farber disease. J Lipid Res. 2010 Dec;51:3542–7. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D010033. These publications describes a substrate that is amenable to high throughput readout of AC activity for drug screening or assays of patient samples. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eliyahu E, Shtraizent N, Shalgi R, et al. Construction of conditional acid ceramidase knockout mice and in vivo effects on oocyte development and fertility. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;30:735–48. doi: 10.1159/000341453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Draper JM, Xia Z, Smith RA, et al. Discovery and evaluation of inhibitors of human ceramidase. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011 Nov;10:2052–61. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saied EM, Arenz C. Inhibitors of Ceramidases. Chem Phys Lipids. 2016 May;197:60–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bai A, Szulc ZM, Bielawski J, et al. Synthesis and bioevaluation of omega-N-amino analogs of B13. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009 Mar 01;17:1840–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bai A, Szulc ZM, Bielawski J, et al. Targeting (cellular) lysosomal acid ceramidase by B13: design, synthesis and evaluation of novel DMG-B13 ester prodrugs. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014 Dec 15;22:6933–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Canals D, Perry DM, Jenkins RW, et al. Drug targeting of sphingolipid metabolism: sphingomyelinases and ceramidases. Br J Pharmacol. 2011 Jun;163:694–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheng JC, Bai A, Beckham TH, et al. Radiation-induced acid ceramidase confers prostate cancer resistance and tumor relapse. J Clin Invest. 2013 Oct;123:4344–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI64791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Korbelik M, Banath J, Zhang W, et al. Interaction of acid ceramidase inhibitor LCL521 with tumor response to photodynamic therapy and photodynamic therapy-generated vaccine. Int J Cancer. 2016 Sep 15;139:1372–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bach A, Pizzirani D, Realini N, et al. Benzoxazolone Carboxamides as Potent Acid Ceramidase Inhibitors: Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Studies. J Med Chem. 2015 Dec 10;58:9258–72. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pizzirani D, Bach A, Realini N, et al. Benzoxazolone carboxamides: potent and systemically active inhibitors of intracellular acid ceramidase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015 Jan 07;54:485–9. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eliyahu E, Shtraizent N, He X, et al. Identification of cystatin SA as a novel inhibitor of acid ceramidase. J Biol Chem. 2011 Oct 14;286:35624–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.260372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morad SA, Tan SF, Feith DJ, et al. Modification of sphingolipid metabolism by tamoxifen and N-desmethyltamoxifen in acute myelogenous leukemia--Impact on enzyme activity and response to cytotoxics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015 Jul;1851:919–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bedia C, Casas J, Andrieu-Abadie N, et al. Acid ceramidase expression modulates the sensitivity of A375 melanoma cells to dacarbazine. J Biol Chem. 2011 Aug 12;286:28200–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pizzirani D, Pagliuca C, Realini N, et al. Discovery of a new class of highly potent inhibitors of acid ceramidase: synthesis and structure-activity relationship (SAR) J Med Chem. 2013 May 09;56:3518–30. doi: 10.1021/jm301879g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Realini N, Solorzano C, Pagliuca C, et al. Discovery of highly potent acid ceramidase inhibitors with in vitro tumor chemosensitizing activity. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1035. doi: 10.1038/srep01035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sakamoto J, Hamada C, Rahman M, et al. An individual patient data meta-analysis of adjuvant therapy with carmofur in patients with curatively resected colon cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005 Sep;35:536–44. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]