Abstract

Lung epithelial cells are increasingly recognized to be active effectors of microbial defense, contributing to both innate and adaptive immune function in the lower respiratory tract. As immune sentinels, lung epithelial cells detect diverse pathogens through an ample repertoire of membrane-bound, endosomal and cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs). The highly plastic epithelial barrier responds to detected threats via modulation of paracellular flux, intercellular communications, mucin production, and periciliary fluid composition. Epithelial PRR stimulation also induces production of cytokines that recruit and sculpt leukocyte-mediated responses, and promotes epithelial generation of antimicrobial effector molecules that are directly microbicidal. The epithelium can alternately enhance tolerance to pathogens, preventing tissue damage through PRR-induced inhibitory signals, opsonization of pathogen associated molecular patterns, and attenuation of injurious leukocyte responses. The inducibility of these protective responses has prompted attempts to therapeutically harness epithelial defense mechanisms to protect against pneumonias. Recent reports describe successful strategies for manipulation of epithelial defenses to protect against a wide range of respiratory pathogens. The lung epithelium is capable of both significant antimicrobial responses that reduce pathogen burdens and tolerance mechanisms that attenuate immunopathology. This manuscript reviews inducible lung epithelial defense mechanisms that offer opportunities for therapeutic manipulation to protect vulnerable populations against pneumonia.

INTRODUCTION

The lung epithelium has long been perceived as a passive conduit for bulk airflow or an inert barrier to gas exchange, seldom encountering microbes and irrelevant to host-pathogen interactions. However, modern molecular techniques have revealed the complexity of the lower respiratory tract microbiome1 and accumulating evidence demonstrate that lung epithelial cells function as important mediators of host defense2. Lung epithelial cells express an expansive complement of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) with oligospecificity for conserved microbial and host motifs. PRR activation by pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or danger associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) initiates signaling cascades that can promote pathogen exclusion or expulsion, recruit and activate leukocyte-mediated defenses, directly kill microbes, and restore host homeostasis. These varied mechanisms provide manifold theoretical opportunities for intervention, and recent studies confirm that epithelial defenses can be therapeutically manipulated to protect the host, even in the setting of immunosuppression or leukodepletion3. This review addresses important lung epithelial pathogen detection and response mechanisms that may be therapeutically manipulated to prevent and treat lower respiratory tract infections in healthy and immunocompromised populations.

INDUCIBLE BARRIER DEFENSES

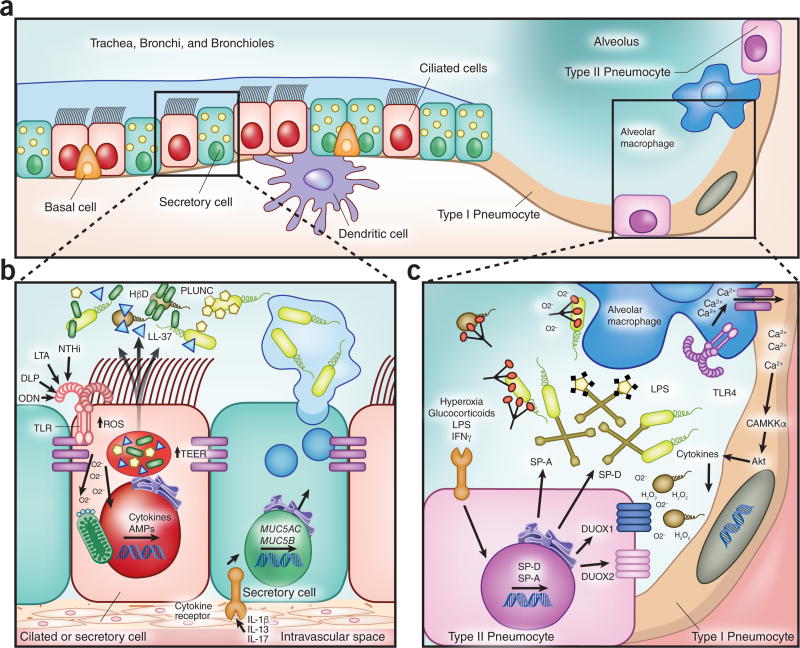

Cellular junctions and cytoskeletal elements

The histological complexity of the lung epithelium portends the specialized functions of its component cells. The pseudostratified airway epithelium is predominantly comprised of ciliated cells and secretory cells, interspersed with regenerative basal cells and neuroendocrine cells (Figure 1A–B). The vast majority of the alveolar epithelial surface area is contributed by exceptionally thin, broad type I pneumocytes that are optimized for gas exchange, while the considerably more numerous type II pneumocytes are principally responsible for secretory functions of the peripheral lung4 (Figure 1A, C). At baseline, these epithelial populations form a continuous 100 m2 barrier interface between the host and the external environment. Following PRR activation, this barrier function can be actively adapted to enhance microbial protection. Tight and adherens junctions, connecting cytoskeletons of apposing cells, modulate paracellular flux of ions and macromolecules through structural protein phosphorylation or translation of alternate tight junction protein isoforms to prevent barrier disruption and lung injury in both the airways and alveolar space5,6. Inducible modification of paracellular permeability regulates access to epithelial receptors for PAMPs, cytokines and intraepithelial leukocytes.7,8 Epithelial tight junctions also contain many potentially targetable signaling molecules, including protein kinase C, Rho proteins, phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase, transcription factors, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family members, such as HER2/3.7,8 For example, Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 stimulation of bronchial epithelial cells can activate PKCζ, increasing claudin-1 expression, thereby enhancing transepithelial electrical resistance and tight junctional integrity.9 Epithelial cytoskeletons can also rearrange to facilitate PRR signaling, and cytoskeletal elements themselves can augment host defenses, as when F-actin released during necrosis activates dendritic cell CLEC9A receptors10 promoting clearance of dying cells and, ultimately, hastening resolution of infection related injury.

Figure 1. Inducible antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of lung epithelial cells.

(A) Cells contributing to inducible epithelial airspace defense. (B) Inducible responses in the conducting airways. Pattern recognition and cytokine receptors detect local danger signals in the conducting airways, responding with enhanced barrier and mucociliary functions to improve pathogen exclusion, increased production of microbicidal antimicrobial peptides and volatile species, and secretion of mediators of leukocyte recruitment and activation. (C) Inducible responses in the alveolar compartment. Epithelial cells in the gas exchange units of the lungs detect pathogen associated molecular patterns, perceive stress signals and communicate with lung resident leukocytes, and respond through inducible modulation of barrier function, enhanced production of antimicrobial peptides, collectins and volatile species, and secretion of leukocyte-active cytokines. TLR, Toll-like receptor; NTHi, non-typeable Haemophillus influenza; LTA, lipotechtoic acid; DLP, diacylated lipopeptides; ODN, oligodeoxynucleotide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TEER, transepithelial electrical resistance; HβD, human β-defensin; SP, surfactant protein.

Perhaps underscoring the importance of these responses, several bacteria possess the ability to enter non-phagocytic cells via cytoskeletal manipulation and form sequestering compartments that promote their own growth. Mitigating this threat, mammalian PRRs such as NOD1, NOD2 and pyrin can sense pathogenic cytoskeletal protein changes, leading to initiation of proinflammatory responses and entrapment of actin-polymerizing bacteria by septin cages11. Thus, while not yet established in practice, manipulation of junctional and cytoskeletal elements may eventually provide valuable opportunities to protect against respiratory infections.

Mucociliary defenses

Particles and microbes entrained into the lower respiratory tract during respiration are impacted into the airway lining fluid by turbulent flow and > 90% are expelled from the lungs via the mucociliary escalator within minutes12. The largest populations of airway epithelial cells, present in roughly equal numbers, are the ciliated cells that beat the airway lining fluid proximally toward the glottis and the secretory cells that, among other things, contribute mucins to the airway lining (Figure 1B). MUC5AC and MUC5B are the most abundantly expressed polymeric secreted mucins in the airways13. In addition to optimizing the viscoelastic properties to the airway lining fluid for particle clearance, there is mounting evidence that gel-forming mucins contribute to antimicrobial responses. Stimulated MUC5B production from epithelial cells has been directly linked to antibacterial defense and enhanced alveolar macrophage function12, and is inducible by PAMPs such as β-glucan14 and by some NF-κB-mediated cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-17A)15. Concordantly, MUC5B deficient mice have been found to be hypersusceptible to pneumonia and to demonstrate impaired pathogen clearance12. MUC5AC is strongly induced by epithelial exposure to IL-13, cathelicidin, and a number of bacterial and viral pathogens,12,16–18 including specificity protein 1 (Sp1)- and EGFR-mediated induction by influenza A19. Cytosolic PRR stimulation may also enhance airway mucin production, as NLRP6 inflammasome activation promotes mucin secretion during colonic bacterial infections, though this is not yet confirmed in the lung20. Active epithelial regulation of periciliary layer pH further augments mucin-facilitated pathogen clearance and defense. The importance of this function is evident in cystic fibrosis, where reduced periciliary pH impairs detachment of submucosal mucins and impedes mucus clearance21. The multiple stimuli capable of inducing MUC5AC and MUC5B secretion suggest their potential as therapeutic targets. While membrane-bound mucins (MUC1, MUC4, MUC16) also facilitate mucociliary escalator function, there is limited evidence that their induction by infectious or pharmacologic stimuli enhances pathogen clearance13. No strategies have definitively shown improved pathogen clearance through ciliary function manipulation in hosts without intrinsic impairments. However, recent data revealing that IL-13-induced bronchial epithelial cell MUC5AC contributes to mucostasis in asthma via tethering of mucus gel domains to the epithelium22 suggest there may be additional opportunities to augment mucociliarly pathogen clearance in patients with baseline defects, beyond inducing mucus production and moderating periciliary pH.

PATHOGEN DETECTION

PRRs are highly conserved across species, emphasizing their importance to host survival.23–25 The broad spectrum of PRRs expressed by lung epithelial cells (Table 1) allow PAMP sensing within most cellular compartments, facilitating rapid responses to infections, and offering abundant opportunities for therapeutic elicitation of protective epithelial functions.

Table 1.

PRRs in the pulmonary epithelium

| Receptor | Canonical Activating Ligands | Upregulated by | Compartment | Adaptor protein | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toll-like Receptors | TLR2/1 | Triacylated lypopeptides (e.g., Pam3CSK4) | P.M. | MyD88 | |

| TLR2/6 | Diacylated lipopeptides (e.g., Pam2CSK4) | Diacylated lipopeptides, ODNs, NTHi | P.M. | MyD88 | |

| TLR3 | dsDNA, poly (I:C) | Poly (I:C) | Endosome | TRIF | |

| TLR4 | LPS, LBP | P.M. | MyD88, TRIF | ||

| TLR5 | Flagellin | P.M. | MyD88 | ||

| TLR7 | ssRNA | Endosome | MyD88 | ||

| TLR8 | ssRNA | Endosome | MyD88 | ||

| TLR9 | CpG ODN | Diacylated lipopeptides, ODNs, NTHI | Endosome | MyD88 | |

| TLR11 | Profilin, flagellin | P.M. | MyD88 | ||

|

| |||||

| NOD-Like Receptors | NOD1 | D-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid | Cytosol | RIP2, ATGL16 | |

| NOD2 | MDP | Cytosol | RIP2, ATGL16 | ||

| NLRP1 | B. anthracis lethal toxin, MDP, ribonucleoside triphosphate | TLR stimulation | Cytosol | ASC inflammasome | |

| NLRP3 | K. pneumonie, S. pneumonie, S. aureus, C. pneumonie, M. tuberculosis, influenza, rhinovirus, RSV, A. fumigatus, ROS, mitochondrial dysfunction, K efflux, Ca mobilization, ATP, uric acid, hyaluronan, silica, asbestos | Host GI microbiota, TLR stimulation | Cytosol | ASC inflammasome | |

| NLRP4 | Unknown | Unknown | Cytosol | Beclin-1 | |

| NAIP | T3SS needle protein (Cpr1), flagellin | Cytosol | NLRP4 inflammasome | ||

| NAIP2 | P. aeruginosa, T3SS (Prg1) | Cytosol | NLRP4 inflammasome | ||

| NAIP5 | Flagellin | Cytosol | NLRC4 inflammasome | ||

| NLRC4 | L. pneumophila, K. pneumonia, flagellum proteins, T3SS | Cytosol | ASC inflammasome | ||

| NLRC5 | Viruses | Cytosol | ASC inflammasome | ||

| NLRX1 | RNA | Mitochondria | MAVS | ||

|

| |||||

| RLRs | RIG-I | 5’PPP-ssRNA, Paramyxoviruses, influenza, Japanese encephalitis virus, reoviruses, flaviviruses | Type 1 IFN | Cytosol | MAVS |

| MDA5 | Poly (I:C), picoraviruses, flaviviruses, reoviruses | Type I IFN | Cytosol | MAVS | |

|

| |||||

| Nucleotide | cGAS | DNA | Cytosol | STING-IRF3 | |

| STING | Cyclic di-nucleotides | E.R. | STING-IRF3 | ||

| IFI16 | DNA | Cytosol | STING | ||

| AIM2 | DNA | Cytosol | AIM2 inflammasome | ||

TLR, toll-like receptor; P.M., plasma membrane; E.M., endoplasmic reticulum; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LBP, lipopolysaccaride-binding protein; ODN, oligodeoxynucleotide; NTHi, non-typeable Haemophilus influenza; MDP, muramyl dipeptide; RSV, respiratory syncitial virus; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; GI, gastrointestinal; TTSS, type three secretion system; RLRs, Rig-I-like receptors; Poly I:C: poly-inosine:poly-cytosine

Toll-like receptors

Lung epithelial cells are reported to express all known human TLRs, including those that localize to the plasma membrane (TLR2/1, TLR2/6, TLR4, TLR5, TLR10) and those that localize to endosomes (TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9)26. N-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domains with varying degrees of N-glycosylation form a characteristic TLR solenoid structure responsible for pathogen sensing27. A single transmembrane domain connects LRR domains to a cytoplasmic Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) C-terminus tail that recruits TIR adaptor proteins to initiate downstream signaling. Despite the structural similarity of TLRs, their ligand specificity and binding sites vary substantially, allowing them to detect a remarkable spectrum of patterns, including such diverse moieties as lipopeptides, nucleic acids, and bacterial proteins, making TLRs frequent targets of studies investigating epithelial manipulation strategies, as outlined below.

NOD-like receptors

NOD-like receptors (NLRs) are soluble cytosolic proteins composed of a C-terminal LRR domain that confers ligand specificity, a central nuclear oligomerization domain (NOD) and a variable N-terminal effector domain28. They are further categorized by their effector domains into caspase recruitment domain (CARD or NLRCs), pyrin domain (PYD or NLRPs) or baculoinhibitor of apoptosis protein domain (NAIPs or NLRBs). The active oligomerization of NLRs, adaptor proteins and caspases comprises inflammasome formation, resulting in cleavage of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms29.

NLRs expressed by lung epithelial cells include NOD1 and NOD2 which bind bacterial peptidoglycan moieties, activating mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase, NF-κB, and autophagic pathways3. Deficiency30 or polymorphisms31 of these receptors results in increased susceptibility to respiratory infections. NLRP1 enhances resistance to pneumonia by detecting virulence factors such as Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin32. NLRP3 is an important bronchial epithelial DAMP sensor during infection33,34, detecting potassium efflux35, excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) production36, or mitochondrial dysfunction37. NLRC4 initiates inflammasome formation following detection of flagellated bacteria such as Legionella pneumophila38, P. auruginosa39, K. pneumoniae, and those expressing type-III secretion systems (T3SS). NLRX1 possesses an N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence and appears to contribute to ROS production by the respiratory chain transport when stimulated by RNA28. In contrast, stimulation of other lung epithelial NLRs, such as NLRC3 and NLRC5, is associated with anti-inflammatory responses40, suggesting that therapeutic targeting of NLRs may allow selective activation or resolution of antimicrobial responses.

Nucleic acid sensors

Microbe- or host-derived nucleic acids, respectively, can serve as PAMPs or DAMPs that initiate antimicrobial responses. In addition to endosomal TLRs, multiple cytosolic receptors detect RNA and DNA in lung epithelial cells41. This prominently includes retinoic acid inducible gene-I (RIG-I) and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5), cytosolic RIG-I-like helicases (RLRs) that sense ssRNA and dsRNA with a 5’ triphosphate motif29. RLR expression is enriched in lung epithelial cells in response to type I interferons42 and signal through the mitochondrial membrane-bound protein MAVS (also known as IPS-1, VISA, and Cardif) to elicit IRF3, IRF7, and NFκB mediated antimicrobial responses. RLR-MAVS signaling is critical to interferon production during RSV pneumonia43, for example, and contributes to infection-induced airway hyperreactivity through increases in metalloproteinase and cathepsin production44. Though less studied, lung epithelial MDA5 may also elicit virus-specific protection in other infection models45.

Independent of TLRs, NLRs and RLRs, lung epithelial cytosolic detection of microbial DNA and cyclic di-nucleotides42 frequently involves signaling via stimulator of interferon genes (STING), an endoplasmic reticulum-localized protein that acts both as a direct receptor for bacteria-produced cyclic dinucleotides and as an adaptor molecule for other cytosolic nucleic acid receptors46,47, such as IFI1648 or DDX41 (which can also detect both DNA and cyclic dinucleotides)49,50. Additionally, 2’3’-cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) is produced by cGAMP synthase (cGAS) in lung cells upon cGAS binding of microbial DNA, resulting in alternate activation of STING by cGAMP51, making both STING and cGAS frequent targets of investigation for potential therapeutic manipulation of responses from the lungs and elsewhere. Other STING-independent lung epithelial DNA sensors such as DAI, AIM2 and LRRFIP152 have been described, although their relevance in inducible lung immunity remains less established.

C-type lectins

Pathogen-derived carbohydrates, including mannose, fucose, and glucans, can be detected by plasma membrane localized C-type lectins. These receptors are widely distributed on epithelial and myeloid cells and allow detection of fungi, viruses and bacteria53. Dectin-1 is expressed in bronchial epithelial cells and mediates inflammatory responses to infections caused by non-typeable Haemophilus influenza (NTHi)54 and a number of fungi55. Surfactant proteins SP-A and SP-D also contain C-type lectin domains, and broadly contribute to host defense via pathogen detection56, in addition to the antimicrobial effects discussed below. Epithelial cells can also detect fungal glucans via the non-lectin containing glycosphingolipid lactosylceramide57.

ANTIMICROBIAL EFFECTOR MOLECULES

Upon PRR activation, lung epithelial cells generate cytokine signals that initiate leukocyte-mediated responses, but they also produce numerous effector molecules that exert directly microbicidal effects (Table 2 and Figure 1) and have been targeted for potential therapeutic induction.

Table 2.

Inducible antimicrobial peptides in the lung

| AMP | Mechanism(s) | Induced by | Observed Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Cationic Peptides | |||

| α-defensin 1 | Membrane disruption | NTHi lysate | Mouse lung homogenates |

| α-defensin 5 | Membrane disruption | Constitutive | Human nasal and bronchial epithelium |

| β-defensin 1 | Membrane disruption, leukocyte chemotaxis | Constitutive | Mouse and human airway cells |

| β-defensins 2 | Membrane disruption, leukocyte chemotaxis | TNF, IL-1β, LTA, LPS, neutrophil elastase, MEF, triacylated lipopeptides, rhinovirus, L-Isoleucine, L. pneumophila | Mouse and human airway cells |

| β-defensin-34, -5, -39 | Membrane disruption | NTHi lysate | Mouse lung homogenates |

| Cathelicidin (hCAP18/LL-37, CRAMP) | Membrane disruption, LPS and DAMP binding, PMN chemotaxis | NTHi lysate, Vitamin D3, TLRs | Human airways and submucosal glands, mouse lung homogenates |

| ELR− CXC chemokines (CXCL-9, -10, -11, -14) | Membrane disruption, inhibition of spore germination | IFNγ | Mouse lungs |

|

| |||

| Anti-proteases | |||

| SLPI | Membrane disruption, inhibition of inflammation | LPS, neutrophil elastase, cytokines, NTHi lysate, TNF, EGF, IL-1, α-defensins | Club, goblet and nasal epithelial cells |

| Elafin | Membrane disruption, inhibition of inflammation. | LPS, neutrophil elastase, cytokines, NTHi lysate, TNF, IL-1 | Airway epithelial cells |

|

| |||

| Iron modulators | |||

| Lactoferrin | Iron sequestration | NTHi lysate | Submucosal glands |

| Lipocalin-2 | Iron siderophore binding | IL-22, NTHI lysate, LPS, IL-1B, IL-17 | Airway epithelial cells |

|

| |||

| Other AMPs | |||

| Lysozyme | β1–4 glycoside hydrolysis of peptidoglycans | NTHi lysate | Airway epithelial cells |

| Collectins (e.g., SP-A, SP-D) | Opsonization, membrane permeabilization | Glucocorticoids, IFNγ, NTHi lysate, hyperoxia, LPS | Type II pneumocytes, Club cells |

| SPLUNC1 (BPIFA1) | LPS and biofilm inhibition | TLR2 agonists (e.g., Pam3CSK4) | Airway and nasal epithelial cells |

AMP, antimicrobial peptide; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; NTHi, non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae; CRAMP, mouse cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide; LTA, lipotechoic acid; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; ELR−, not containing glutamate-leucine-arginine sequence; SLPI, secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor; SP, surfactant protein; SPLUNC1, short palate, lung, and nasal epithelial clone 1; BPIFA1, BPI fold containing family A member 1; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

Cathelicidin and defensins

Small cationic antimicrobial proteins (AMPs) are frequently synthetized as pre-pro-peptides that are cleaved before secretion to expose share positively-charged moieties that disrupt negatively-charged microbial membranes58,59, as is the case for lung epithelial defensins and cathelicidin60. Defensins are amphipathic molecules that a common γ-core region and are further subdivided into α-defensins and β-defensins based on disulfide bridge arrangement. Although previously thought to express only β-defensins, recent data indicate that murine lung epithelial cells also produce α-defensin 561 and α-defensin 1 following exposure to bacterial lysates62. The only human cathelicidin, hCAP18, possess two characteristic hydrophobic α-helix domains63. hCAP18 is stored in preformed granules and, upon stimulation, is cleaved on its N-terminal domain to its active form, LL373. LL37 is secreted by airway and submucosal gland epithelial cells and is believed to electrostatically disrupt bacterial membranes64. The functions of epithelial defensins and LL-37 are multiple, both selectively promoting and attenuating different elements of the inflammatory response.60,65 When induced by infections, both act as chemoattractants for neutrophils, dendritic cells, T cells, macrophages, and monocytes66–68. LL-37 also interacts synergistically with IL-1β to promote local inflammatory cytokine production69. However, its binding of negatively charged molecules also allows LL-37 to sequester LPS and certain DAMPs (e.g., self-DNA and RNA), thereby attenuating other inflammatory responses70–72.

Antiproteases

Lung cells express secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) and elastin specific inhibitor (elafin) in response to stimuli such as LPS, IL-1β and TNF73. SLPI is expressed in the airway mucosa60 and inhibits neutrophil elastase, chymotrypsin, and cathepsin G, but notably also exerts directly antimicrobial effects on bacteria (P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, E. coli), fungi (C. albicans, A. fumigatus), and HIV74,75. Similarly, elafin has direct antimicrobial activity against P. aeruginosa and S. aureus.76 Further, both of these antiproteases demonstrate immunomodulatory activity on macrophages and endothelial cells following epithelial stimulation, decreasing IκBα degradation77 and increasing production of TGFβ and IL-1078. Properties promoting tissue repair and resolution of inflammation have also been attributed to SLPI and elafin79.

Chemokines

Cytokine and chemokine production are essential to epithelial modulation of immune responses, but some IFNγ-induced epithelial chemokines, including CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, also demonstrate directly bactericidal effects on B. anthracis, E. coli, and L. monocytogenes,80,81 likely via membrane disruption, given their defensin-like α-helical domains. The N-terminal domain of CXCL14 also appears to affect the integrity of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial membranes82.

Lysozyme, lactoferrin and lipocalin 2

Human lysozyme and mouse lysozyme-1 and -2 are abundantly expressed by lung airway and submucosal gland epithelial cells83, catalyzing hydrolysis of β1–4 glycosidic bonds in bacterial peptidoglycan3. This effect is sufficiently robust that transgenic mice overexpressing lysozyme display decreased susceptibility to pneumonias caused by P. aureginosa and Group B Streptococci84. Lactoferrin is a cationic glycoprotein that can bind both free iron and bacterial membrane components60, impairing bacterial growth. While the isolated effects of epithelial lysozyme and lactoferrin are predominantly bacteriostatic at physiologic concentrations, together they synergize to exert bactericidal effects85. Lysozyme’s activity on Gram-negative bacteria is enhanced by lactoferrin increasing the permeability of bacterial outer membranes, facilitating cleavage of peptidoglycan bonds in the periplasmic space. Consistent observations of this positive interaction have promoted numerous studies of therapeutic supplementation with combinations of recombinant antimicrobial effectors. Lipocalin 2 is a secreted protein that is also induced by DAMPs and cytokines in multiple cell types, including lung epithelial cells,62,86–88 and has been found to be important in host responses against K. pneumoniae and E. coli. Similar to lactoferrin, lipocalin 2 has the ability to sequester iron from siderophores, though it appears likely that additional iron-independent mechanisms also contribute to its antibacterial effect.

Collectins

Lung epithelial collectins (collagen-containing C-type lectins), prominently including SP-A and SP-D, function as soluble PRRs in the airspaces that polymerize into large scaffolds and opsonize or aggregate microbes. SP-A and SP-D expression by type II alveolar epithelial cells and club cells increases in responses to LPS, glucocorticoids, hyperoxia, bacterial lysates, and IFNγ62,89, suggesting they may be accessible therapeutic targets. SP-A- and SP-D-mediated opsonization enhances microbial clearance by alveolar macrophages (Figure 1C), while their deficiency increases susceptibility to Group B Streptococci, Gram-negative bacteria, RSV, influenza A, and adenoviruses90. SP-A and SP-D are also reported to disrupt bacterial membrane permeability of some Gram-negative bacteria91.

PLUNC proteins

Palate-lung-nasal-clone (PLUNC) family proteins are secreted by cells throughout the lung and nasal mucosa. SPLUNC1 is induced by TLR2 stimulation in a MAP kinase/AP-1 and NF-κB-dependent matter92. Their antimicrobial properties are thought to relate to their structural homology with LPS binding proteins, though they may also function as surfactant proteins, and possibly inhibit biofilm formation93. SPLUNC1 deficient mice are susceptible to P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae pneumonia, and demonstrate impaired production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and other AMPs94,95.

Reactive oxygen species and ion transport

ROS are increasingly recognized to function as direct antimicrobial effector molecules, most likely through lipid peroxidation of microbial membranes and DNA damage, in addition to their well-established roles as signaling molecules. Lung epithelial cells generate ROS both constitutively and inducibly, most abundantly as superoxide or hydrogen peroxide. While all NADPH oxidase (NOX) isoforms are reportedly found in the lungs, dual oxidases (DUOX) are the principal ROS generators of lung epithelial cells. DUOX1 produces a relatively consistent amount of ROS, though recent evidence indicates that this production can be moderately enhanced by IL-4 and IL-13 exposure96. In contrast, DUOX2-dependent ROS production can be profoundly increased by activation of existing DUOX2 and increased DUOX2 and DUOXA2 transcription following exposure to cytokines such as IFNγ96, an intervention that has been shown in vitro to reduce pathogen burdens. DUOX enzyme activity is regulated by calcium concentrations and they are predominantly expressed apically on ciliated airway epithelial cells and on type II alveolar epithelial cells, approximating the enzymes to microbes that gain access to the airspaces97 (Figure 1C). In addition to toxic effects of the volatile species directly on pathogens, submucosal epithelial cell-derived lactoperoxidase catalyzes a reaction between epithelial hydrogen peroxide and thiocyanate to form the highly microbicidal molecule hypothiocyanate.

As observed in cystic fibrosis, impaired anion transport due to CFTR mutations causes decreased bicarbonate secretion, resulting in reduced periciliary pH and impaired AMP function98. Additionally, active epithelial ion transport is required to provide halide (chloride, bromide, iodide) and pseudohalide (thiocyanate) substrates for ROS-mediated antimicrobial defenses99. Thus, investigators have variously proposed to stimulate DUOX activity in the lungs, modify ion channel activity, and enhance halide/pseudohalide availability as means to enhance antimicrobial defenses of the lungs.

EPITHELIAL MODULATION OF IMMUNE RESPONSES AND TOLERANCE

PRR elicited epithelial cytokines importantly participate in the recruitment and activation of leukocytes in the lung. Beyond simply increasing the number of leukocytes present, epithelial cell responses clearly modulate adaptive immune responses in the lung during infections.

Modulation of inflammation

Lung epithelial cells have long been recognized to demonstrate profound asthmatic/allergic phenotypes when exposed to IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13. However, it is now evident that they are also capable of autonomously promoting or initiating type 2 inflammatory responses. A typical example of this is TLR4-mediated detection of house dust mite antigen100 by club cells, resulting in allergic cytokine secretion and Th2 immune deviation. This epithelial exposure promotes production of IL-33, TSLP, and IL-25, stimulating DCs to subsequently activate type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2), basophils, eosinophils and mast cells101. Epithelial GM-CSF is also secreted in response to allergens and induces maturation, proliferation and activation of antigen presenting cells that drive type 2 responses102. Infection-released DAMPs also contribute to epithelial type 2 immune deviation. Epithelial cells respond to uric acid and ATP that are released into the airway in response to allergens, further releasing IL-33 and TSLP103,104. While type 2 deviation is often regarded as maladaptive (i.e., allergy) or relevant only to parasitic diseases, it has been shown that enhanced CCL8 production and neutrophil recruitment associated with type 2 responses augment clearance of K. pneumoniae105. Type 1 and type 17 inflammation are more commonly regarded as protective against respiratory pathogens, and lung epithelial cells are analogously capable of deviating immune responses to these patterns, as well. For example, lung cells express IFN-ϒ in response to mycobacterial and fungal infections, promoting protective type 1 inflammatory deviation106,107 Similarly, not only do lung epithelial cells produce brisk cytokine responses when exposed to IL-17A and IL-17F, but epithelial production of IL-6, TGFβ, and IL-21 (also possibly IL-23) can enhance differentiation of Th17 cell differentiation108–111 sculpting local adaptive responses in response to PAMP exposure.

Tolerance and downregulation of inflammation

Host survival of pathogen challenges depends on two fundamental strategies: resistance and tolerance. Resistance relies upon reductions in the microbial burden to limit injury and preserve fitness. Alternately, tolerance promotes survival through host adaptations to limit the pathogen’s ability to inflict damage or to reduce noxious and/or maladaptive responses associated with host defenses (immunopathology), rather than eliminating the pathogen112. Literature describing infection tolerance in the lung remains limited, and studies describing therapeutic manipulation are rarer still. However, induction of host-protective responses, rather than pathogen-toxic elements, holds promise as a strategy that could be applicable in many infectious or inflammatory conditions.

For example, recent studies indicate that alveolar epithelial cells communicate with alveolar macrophages through connexins via calcium spikes during LPS-induced inflammation113. This communication activates Akt-dependent signal propagation through adjacent cells, reducing neutrophil chemotaxis and proinflammatory cytokine release. These counterbalance proinflammatory responses in the lung, attenuating immunopathology. Similarly, the mucin MUC1 is induced by epithelial exposure to TNF and IL-8114, and can regulate inflammation during bacterial infections through inhibition of TLR signaling115,116. While MUC1-deficient mice show enhanced P. aeruginosa clearance following intranasal challenge, they also exhibit higher inflammatory chemokine expression, and greater neutrophil influx, resulting in greater immunopathology117.

The lungs also mitigate immunopathology via inhibitory feedback from the antimicrobial effector molecules described above. For example, epithelium-derived LL-37 can sequester LPS72 and decrease cytokine release118 to dampen immune responses. Similarly, epithelial α-defensin 1 can actively attenuate phagocyte ROS burst during influenza infections without impairing viral resistance119. Further preventing immunopathology, epithelial cells produce mediators that promote resolution of inflammation, induce apoptosis, and decrease neutrophil chemotaxis120,121. Polyunsaturated fatty acids present in epithelial cell membranes can be enzymatically converted to resolvins, maresins, protectins, and lipoxins. These molecules decrease pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, attenuate neutrophil oxidative burst, and decrease leukocyte chemotaxis, though their therapeutic inducibility remains largely untested.

THERAPEUTIC MANIPULATION OF EPITHELIAL IMMUNITY

The inducibility of the aforementioned epithelial defenses has prompted several groups to investigate exploitation of these mechanisms to protect against pneumonia. This approach offers an appealing complement to conventional antibiotic treatment, due to the lack of documented antibiotic resistance and broad protection that generally does not require prior pathogen identification. The most commonly applied strategies are exposure of lung cells to synthetic PRR ligands and the exogenous administration of AMPs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Targeted therapies for innate immunity in lung infections

| Component | Receptor/Ligand | Route | Protects against | Presumed mechanism | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern-recognition Receptors | UC-1V150 | TLR7 | I.T. | B. anthracis, influenza H1N1, VEE | IFN induction | 126 |

| 3M-011 | TLR7 and TLR8 | I.N. | Influenza virus | IFNα induction | 129 | |

| PO R10-60 | TLR9 | I.N. | B. anthracis | 130 | ||

| Poly (I:C) | TLR3 | I.N. | P. aeruginosa, F. tularensis, influenza A | Chemokine induction | 127 | |

| Pam2CSK4 + ODNM62 | TLR2/6 and TLR9 | Nebulized | S. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, B. anthracis, influenza A, A. fumigatus | AMP and ROS generation | 132–134,155,156 | |

| Flagellin | TLR5 | I.N. | S. pneumoniae and influenza A | Neutrophil recruitment | 157 | |

| 5’pppRNA | RIG-I | I.V. | VSV, Dengue, Vaccinia, HIV, H1N1 influenza | Type 1 IFN induction | 135,139 | |

| Eritoran (E5564) | TLR4 antagonist | I.V. | Influenza A | Proinflammatory cytokine blockade | 136 | |

| AGP | TLR4 | I.N. | F. novicida | IFNγ induction | 131 | |

| CpG ODN | TLR9 | I.T. | K. pneumonie | IFNγ and chemokine induction | 158 | |

|

| ||||||

| Antimicrobial Peptides | LL-37 | I.T. | P. aeruginosa, MRSA, RSV, M. tuberculosis, | Membrane disruption | 142,159 | |

| CAP18 | I.T. | P. aeruginosa | Chemokine induction | 118 | ||

| L-isoleucine | I.T. | Multidrug resistant M. tuberculosis | HBD-2 induction | 145 | ||

| Novospirin G10 | I.T. | P. aeruginosa | Direct microbicidal | 146 | ||

| β-defensin 2 | I.T. | P. aeruginosa | HBD-2 upregulation | 144 | ||

AMP, antimicrobial peptide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; IFN, interferon; TLR, Toll-like receptor; I.T., intratracheal; I.N., intranasal; I.V., intravenous; AGP, amynoalkyl-glucosamine phosphate; VEE, venezuelan equine encephalitis virus; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; HBD, human beta defensin.

Targeting of PRRs

Early attempts to therapeutically harness inducible lung epithelial antimicrobial responses often centered on efforts to broadly stimulate PRRs by simulating native infections prior to experimental challenges3. Typical of this nontargeted approach to PRR stimulation was intrapulmonary treatment of mice or isolated lung cells with noncognate bacterial lysates prior to pneumonia challenge. Exposing mice to the myriad PAMPs in a bacterial lysate induces robust responses that were shown to be protective against a wide range of otherwise lethal pathogens, including B. anthracis, Y. pestis, F. tularensis, S. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, influenza A, and Aspergillus fumigatus62,122. The protection was uniformly associated with pathogen killing in the lungs, and noted to correlate with enrichment of numerous antimicrobial molecules such as cathelicidin, defensins, lipocalin 2, surfactant proteins, orosomucoids, and calprotectins62, suggesting activation of many of the above described processes. While treatment with crude lysates neither answered the questions of which PRRs were required for protection nor leant itself particularly well to clinical development, the finding that inducible protection was completely lost in MyD88 deficient mice123 suggested that focused targeting of specific PRR population might be successful.

TLR stimulation

A substantial majority of studies investigating targeted PRR stimulation in the lungs have focused on manipulation of TLRs. The broad array of TLRs expressed by airway cells makes intrapulmonary administration of TLR agonists a conceptually attractive means of inducing resistance. Since shortly after the discovery of mammalian TLRs, investigators have delivered TLR agonists systemically to animals to initiate or modify leukocyte-mediated immunity, including efforts attempting to elicit secondary antimicrobial responses from intestinal epithelial cells. However, the presence of TLRs at the accessible environmental interface of the lungs allows for direct action on epithelial cells, which is a fundamentally different strategy than eliciting responses from circulating or intraepithelial leukocytes that then act on epithelial cells. In many cases, TLR ligands previously used to study signaling pathways have been repurposed for intrapulmonary delivery, with some ligands modified and/or conjugated to improve bioavailability and pharmacokinetics. For instance, intranasal delivery of a purified TLR5 agonist (flagellin) to the lungs protected mice against otherwise lethal P. aeruginosa pneumonia. This protection was partially dependent upon cathelicidin induction and persisted when neutrophils were depleted124. A related strategy delivering intranasal pretreatment with an albumin-conjugated TLR7 agonist (UC-1V150) protected mice against pneumonia caused by B. anthracis or H1N1 influenza. This enhanced survival correlated with increased airway cytokine and chemokine production.125,126 Similarly, intranasal administration of a TLR3 agonist (poly I:C) during a cecal ligation and puncture sepsis model enhanced survival and decreased lung bacterial burdens following a secondary P. aeruginosa pneumonia challenge.127 Prophylactic or post-exposure intranasal poly I:C treatment also enhanced survival of F. tularensis pneumonia in a manner that was associated with increased local cytokine secretion and neutrophil influx to the airway, along with decreased lung pathogen burden.128 Another study of intranasal pretreatment of the lungs with a TLR7/8 agonist (3M-011) enhanced H3N2 influenza clearance in a rat model of pneumonia, noting the viral titer reductions to correlate with increases in TNF, IL-12 p40/70, and type I IFNs.129 Intranasal prophylactic TLR9 stimulation with a phosphodiester-oligodeoxynucleotide (PO R10-60) also protected mice against B. anthracis pneumonia, and increased inflammatory cytokines and type I interferons in lavage fluid.130 In a model of pneumonic tularemia, mice treated with the synthetic TLR4 ligand aminoalkyl glucosaminide phophate (AGP) before and after infection displayed increased survival. This protection was dependent on neutrophil influx and cytokine production in the airway and was lost in IFNγ knockout mice.131

The broad protection induced by nontargeted stimuli (e.g., bacterial lysates), the robust responses generated by intrapulmonary application of specific ligands, and the positive microbicidal interactions observed when combining antimicrobial effector molecules together suggest that combinations of TLR stimuli might confer greater pneumonia protection than achieved with a single ligand. This hypothesis is supported by studies such as those testing concurrent inhalational administration of a TLR2/6 ligand (Pam2CSK4) and a TLR9 ligand (ODN M362) that synergistically interact to robustly protect mice against viral, bacterial and fungal pneumonia132,133. Protection induced by the synergistic inhaled TLR ligands is dependent upon lung epithelial TLR signaling and is associated with production of both ROS and AMPs134.

Notably, all of the TLR agonist treatments described above initiate local inflammatory responses, and the reported survival benefits are all associated with reduced lung pathogen burdens, suggesting generation of a microbicidal environment. Further, all of the foregoing TLR stimulation strategies are presumed to predominantly engage lung epithelial TLRs, based on their delivery to the airways via intranasal, intratracheal or inhalational exposure. While epithelial cells comprise the vast majority of the treated surface area, TLRs on other cells (particularly, leukocytes) also encounter the ligands and likely generate relevant responses, as well. Thus, although the epithelial TLR requirement is established in these various treatments by loss of protection when TLR signaling is conditionally disrupted in the lung epithelium and/or by recapitulation of the antimicrobial phenomena when epithelial cells are studied in isolation122,125,127,130,134,135, in vivo sufficiency of the epithelium to effect the complete phenotype is seldom established.

TLR inhibition

The immunopathology caused by excessive inflammation induced by certain infections may exceed the injury caused by pathogen virulence factors. In these cases, induction of tolerance may be a better strategy to survive infection. Mice lacking TLR4 seem to have an increased tolerance to influenza and inhibition of TLR4 signaling with eritoran 2 days after established infection decreased viral titers, alveolar inflammation, cytokine secretion, and overall survival136. Although this strategy has been investigated in the clinical context of sepsis, it has not been demonstrated to improve overall mortality and it risks rendering the host susceptible to death by secondary bacterial pneumonia137, potentially limiting its current applicability.

RIG-I stimulation

A synthetic 5’-triphosphate RNA RIG-I ligand (M8) has been shown to initiate protective responses against viral infections. Similar to several synthetic TLR agonists, M8 induces antiviral responses from isolated A549 lung epithelial cells against both RNA and DNA viruses. However, although in vitro epithelial responses have been demonstrated and intravenous injection of M8 before challenge with H1N1 influenza increased survival and decreased viral titers in the lung138,139, there remain no in vivo data following direct intrapulmonary administration.

Effector molecule supplementation

Antimicrobial peptides

In vitro investigations using synthetic small cationic AMPs have long offered promise as microbicidal interventions, although the ion charges and concentrations used in pathogen killing experiments may be meaningfully different from in vivo conditions. In fact, survival benefit following in vivo administration of cationic peptides appears to largely rely on their ability to modulate inflammatory responses in the lungs, with rather inconsistent antimicrobial effects.140,141 For example, while it was found that synthetic human LL-37 instilled intranasally during P. aeruginosa infection decreased the pulmonary pathogen burden at 24 hours, there was no bacterial difference at earlier time points and enhanced survival appeared to correlate more strongly with neutrophil chemotactic properties of LL-37142. This is concordant with other reports that LL-37 instillation promotes recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes143. Intratracheal delivery of a related rabbit derived molecule cationic antimicrobial peptide 18 (CAP18) also enhanced mouse survival of P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Similar to LL-37, the survival advantage was not associated with differences in bacterial burdens, but there was a significant decrease in proinflammatory interleukins in lavage fluid.118 Human beta-defensin-2 (HBD-2) is a highly inducible airway epithelial AMP. Overexpression of HBD-2 prior to intratracheal P. aeruginosa infection, attenuates lung inflammation and a significantly increases survival144. Similarly, in a pulmonary multidrug resistant M. tuberculosis model, intratracheal administration of L-isoleucine 60 days after infection significantly increased mBD-3 (the murine ortholog of HBD-2). This increase was associated with a decreased bacterial burdens and pneumonia extent145, as well as increased levels of lung TNF and IFNγ. Novispirin G10, a cationic protein isolated from sheep neutrophils, delivered to rats intratracheally immediately after infection with P. aeruginosa significantly decreased bacterial burdens and lung damage compared to sham treatment, although no survival difference was noted146. IL-22 which can upregulate Lipcocalin-2 has been shown to rescue IL-23 deficient mice in the setting of acute K. pneumoniae infection88. The lung epithelium also expresses members of the regenerating islet-derived proteins which can bind peptidoglycan on gram positive bacteria147. These proteins are STAT3-regulated and undergo post-translational modification in the lung to exert bactericidal activity against MRSA148. Collectively, these examples demonstrate that therapeutically supplemented AMPs frequently elicit effects by both microbicidal and immunomodulatory mechanisms, just as observed with native AMP induction.

Relatedly, cytokine supplementation has been undertaken with the intent of modulating immune responses, but as discussed above, several of these molecules also possess antimicrobial activity. Thus, their supplementation may directly reduce pathogen burden, as well.

Alternate strategies

Although induction of epithelial ROS can kill pathogens, direct supplementation of ROS or other volatiles to the lung is generally not feasible. However, dietary supplementation or nebulized delivery of halide and pseudohalide substrates to the lung epithelium can enhance peroxidase-catalyzed production of highly microbicidal, ROS-dependent molecules (e.g., hypothiocyanate, hypoiodous acid, hypochlorous acid). To date, these studies have been associated with increases in the investigated antimicrobial molecules and reductions in pathogen burdens99,149,150, but have not demonstrated enhanced pneumonia survival.

Another epithelium-targeted strategy to protect against pneumonia is the potentiation of antimicrobial and mucociliary function through manipulation of periciliary pH. In piglets with cystic fibrosis, inhalation of bicarbonate or tromethamine increases periciliary pH, enhancing the bactericidal function of AMPs151. This may explain the decrease in P. aeruginosa colonization in patients treated with the CFTR potentiator ivacaftor152,153. Reports describing successful manipulation of barrier function or induction of pneumonia tolerance remain lacking. However, TLR5 stimulation has been shown to reduce immunopathology in other conditions, such as radiation injury154, so targeting these elements of epithelial defense may be feasible.

CONCLUSIONS

Taken together, the lung epithelium is capable of significant antimicrobial responses and actively participates in different threat-reduction strategies against pathogen load and noxious stimuli. It is possible to take advantage of these mechanisms to prevent infection during peak susceptibility periods despite leukocyte dysfunction or depletion. Further research in mucosal innate immunity will provide insight into potential targeted therapies for induction of epithelial antimicrobial responses and prevention of lung injury in humans.

Acknowledgments

S.E.E. is an author on US patent 8 883 174 entitled “Stimulation of Innate Resistance of the Lungs to Infection with Synthetic Ligands” and owns stock in Pulmotect, Inc., which holds the commercial options on these patent disclosures.

Sources of support:

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL117976 and DP2 HL123229 to S.E.E.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

M.M.L.-J. declares no conflicts of interest.

J.K.K. declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dickson RP, Huffnagle GB. The Lung Microbiome: New Principles for Respiratory Bacteriology in Health and Disease. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004923. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitsett JA, Alenghat T. Respiratory epithelial cells orchestrate pulmonary innate immunity. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:27–35. doi: 10.1038/ni.3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans SE, Xu Y, Tuvim MJ, Dickey BF. Inducible innate resistance of lung epithelium to infection. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:413–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franks TJ, et al. Resident cellular components of the human lung: current knowledge and goals for research on cell phenotyping and function. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:763–766. doi: 10.1513/pats.200803-025HR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He D, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid enhances pulmonary epithelial barrier integrity and protects endotoxin-induced epithelial barrier disruption and lung injury. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24123–24132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wray C, et al. Claudin-4 augments alveolar epithelial barrier function and is induced in acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L219–227. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00043.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies DE. Epithelial barrier function and immunity in asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(Suppl 5):S244–251. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201407-304AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brune K, Frank J, Schwingshackl A, Finigan J, Sidhaye VK. Pulmonary epithelial barrier function: some new players and mechanisms. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L731–745. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00309.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ragupathy S, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 regulates the barrier function of human bronchial epithelial monolayers through atypical protein kinase C zeta, and an increase in expression of claudin-1. Tissue Barriers. 2014;2:e29166. doi: 10.4161/tisb.29166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sancho D, et al. Identification of a dendritic cell receptor that couples sensing of necrosis to immunity. Nature. 2009;458:899–903. doi: 10.1038/nature07750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mostowy S, et al. Entrapment of intracytosolic bacteria by septin cage-like structures. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy MG, et al. Muc5b is required for airway defence. Nature. 2014;505:412–416. doi: 10.1038/nature12807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fahy JV, Dickey BF. Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2233–2247. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YD, Bae CH, Song SY, Choi YS. Effect of β-glucan on MUC4 and MUC5B expression in human airway epithelial cells. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5:708–715. doi: 10.1002/alr.21549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujisawa T, et al. NF-κB mediates IL-1β- and IL-17A-induced MUC5B expression in airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:246–252. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0313OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voynow JA, Rubin BK. Mucins, mucus, and sputum. Chest. 2009;135:505–512. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, et al. The human Cathelicidin LL-37 induces MUC5AC mucin production by airway epithelial cells via TACE-TGF-α-EGFR pathway. Exp Lung Res. 2014;40:333–342. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2014.926434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holtzman MJ, et al. Immune pathways for translating viral infection into chronic airway disease. Adv Immunol. 2009;102:245–276. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(09)01205-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barbier D, et al. Influenza A induces the major secreted airway mucin MUC5AC in a protease-EGFR-extracellular regulated kinase-Sp1-dependent pathway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47:149–157. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0405OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wlodarska M, et al. NLRP6 inflammasome orchestrates the colonic host-microbial interface by regulating goblet cell mucus secretion. Cell. 2014;156:1045–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoegger MJ, et al. Impaired mucus detachment disrupts mucociliary transport in a piglet model of cystic fibrosis. Science. 2014;345:818–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1255825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonser LR, Zlock L, Finkbeiner W, Erle DJ. Epithelial tethering of MUC5AC-rich mucus impairs mucociliary transport in asthma. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:2367–2371. doi: 10.1172/JCI84910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roach JC, et al. The evolution of vertebrate Toll-like receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9577–9582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502272102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burch-Smith TM, Dinesh-Kumar SP. The functions of plant TIR domains. Sci STKE. 2007;2007:pe46. doi: 10.1126/stke.4012007pe46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spätzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell. 1996;86:973–983. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gay NJ, Symmons MF, Gangloff M, Bryant CE. Assembly and localization of Toll-like receptor signalling complexes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:546–558. doi: 10.1038/nri3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Botos I, Segal DM, Davies DR. The structural biology of Toll-like receptors. Structure. 2011;19:447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaput C, Sander LE, Suttorp N, Opitz B. NOD-Like Receptors in Lung Diseases. Front Immunol. 2013;4:393. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broz P, Monack DM. Newly described pattern recognition receptors team up against intracellular pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:551–565. doi: 10.1038/nri3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Divangahi M, et al. NOD2-deficient mice have impaired resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection through defective innate and adaptive immunity. J Immunol. 2008;181:7157–7165. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7157. doi:181/10/7157 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin CM, Ma X, Graviss EA. Common nonsynonymous polymorphisms in the NOD2 gene are associated with resistance or susceptibility to tuberculosis disease in African Americans. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1713–1716. doi: 10.1086/588384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chavarría-Smith J, Vance RE. Direct proteolytic cleavage of NLRP1B is necessary and sufficient for inflammasome activation by anthrax lethal factor. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003452. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Nardo D, De Nardo CM, Latz E. New insights into mechanisms controlling the NLRP3 inflammasome and its role in lung disease. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kostadinova E, et al. NLRP3 protects alveolar barrier integrity by an inflammasome-independent increase of epithelial cell adherence. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30943. doi: 10.1038/srep30943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pétrilli V, et al. Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1583–1589. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dostert C, et al. Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science. 2008;320:674–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2011;469:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berrington WR, Smith KD, Skerrett SJ, Hawn TR. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing-like receptor family, caspase recruitment domain (CARD) containing 4 (NLRC4) regulates intrapulmonary replication of aerosolized Legionella pneumophila. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:371. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tolle L, et al. Redundant and cooperative interactions between TLR5 and NLRC4 in protective lung mucosal immunity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Innate Immun. 2015;7:177–186. doi: 10.1159/000367790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schneider M, et al. The innate immune sensor NLRC3 attenuates Toll-like receptor signaling via modification of the signaling adaptor TRAF6 and transcription factor NF-κB. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:823–831. doi: 10.1038/ni.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma S, Fitzgerald KA. Innate immune sensing of DNA. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001310. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Opitz B, van Laak V, Eitel J, Suttorp N. Innate immune recognition in infectious and noninfectious diseases of the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1294–1309. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1427SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhoj VG, et al. MAVS and MyD88 are essential for innate immunity but not cytotoxic T lymphocyte response against respiratory syncytial virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14046–14051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foronjy RF, et al. Type-I interferons induce lung protease responses following respiratory syncytial virus infection via RIG-I-like receptors. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:161–175. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kato H, et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. doi:nature04734 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ishikawa H, Barber GN. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature. 2008;455:674–678. doi: 10.1038/nature07317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burdette DL, Vance RE. STING and the innate immune response to nucleic acids in the cytosol. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:19–26. doi: 10.1038/ni.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Unterholzner L, et al. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:997–1004. doi: 10.1038/ni.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Z, et al. The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:959–965. doi: 10.1038/ni.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parvatiyar K, et al. The helicase DDX41 recognizes the bacterial secondary messengers cyclic di-GMP and cyclic di-AMP to activate a type I interferon immune response. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1155–1161. doi: 10.1038/ni.2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu J, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science. 2013;339:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1229963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang P, et al. The cytosolic nucleic acid sensor LRRFIP1 mediates the production of type I interferon via a beta-catenin-dependent pathway. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:487–494. doi: 10.1038/ni.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geijtenbeek TB, Gringhuis SI. Signalling through C-type lectin receptors: shaping immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:465–479. doi: 10.1038/nri2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heyl KA, et al. Dectin-1 is expressed in human lung and mediates the proinflammatory immune response to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. MBio. 2014;5:e01492-01414. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01492-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drummond RA, Lionakis MS. Mechanistic Insights into the Role of C-Type Lectin Receptor/CARD9 Signaling in Human Antifungal Immunity. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2016;6:39. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nayak A, Dodagatta-Marri E, Tsolaki AG, Kishore U. An Insight into the Diverse Roles of Surfactant Proteins, SP-A and SP-D in Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Front Immunol. 2012;3:131. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Evans SE, et al. Pneumocystis cell wall beta-glucans stimulate alveolar epithelial cell chemokine generation through nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent mechanisms. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:490–497. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0300OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kolls JK, McCray PB, Chan YR. Cytokine-mediated regulation of antimicrobial proteins. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:829–835. doi: 10.1038/nri2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ganz T. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:710–720. doi: 10.1038/nri1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lecaille F, Lalmanach G, Andrault PM. Antimicrobial proteins and peptides in human lung diseases: A friend and foe partnership with host proteases. Biochimie. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frye M, et al. Expression of human alpha-defensin 5 (HD5) mRNA in nasal and bronchial epithelial cells. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:770–773. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.10.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Evans SE, et al. Stimulated innate resistance of lung epithelium protects mice broadly against bacteria and fungi. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:40–50. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0260OC. doi:2008-0260OC [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zanetti M. Cathelicidins, multifunctional peptides of the innate immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:39–48. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0403147. jlb.0403147 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bals R, Wang X, Zasloff M, Wilson JM. The peptide antibiotic LL-37/hCAP-18 is expressed in epithelia of the human lung where it has broad antimicrobial activity at the airway surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9541–9546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Akiyama T, et al. The human cathelicidin LL-37 host defense peptide upregulates tight junction-related proteins and increases human epidermal keratinocyte barrier function. J Innate Immun. 2014;6:739–753. doi: 10.1159/000362789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.De Yang, et al. LL-37, the neutrophil granule- and epithelial cell-derived cathelicidin, utilizes formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) as a receptor to chemoattract human peripheral blood neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1069–1074. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang D, et al. Beta-defensins: linking innate and adaptive immunity through dendritic and T cell CCR6. Science. 1999;286:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Z, et al. Evidence that cathelicidin peptide LL-37 may act as a functional ligand for CXCR2 on human neutrophils. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3181–3194. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu J, et al. Host defense peptide LL-37, in synergy with inflammatory mediator IL-1beta, augments immune responses by multiple pathways. J Immunol. 2007;179:7684–7691. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7684. doi:179/11/7684 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ganguly D, et al. Self-RNA-antimicrobial peptide complexes activate human dendritic cells through TLR7 and TLR8. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1983–1994. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lande R, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature. 2007;449:564–569. doi: 10.1038/nature06116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mookherjee N, et al. Modulation of the TLR-mediated inflammatory response by the endogenous human host defense peptide LL-37. J Immunol. 2006;176:2455–2464. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2455. doi:176/4/2455 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Williams SE, Brown TI, Roghanian A, Sallenave JM. SLPI and elafin: one glove, many fingers. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110:21–35. doi: 10.1042/CS20050115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tomee JF, Hiemstra PS, Heinzel-Wieland R, Kauffman HF. Antileukoprotease: an endogenous protein in the innate mucosal defense against fungi. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:740–747. doi: 10.1086/514098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hiemstra PS, et al. Antibacterial activity of antileukoprotease. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4520–4524. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4520-4524.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Simpson AJ, Maxwell AI, Govan JR, Haslett C, Sallenave JM. Elafin (elastase-specific inhibitor) has anti-microbial activity against gram-positive and gram-negative respiratory pathogens. FEBS Lett. 1999;452:309–313. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00670-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Henriksen PA, et al. Adenoviral gene delivery of elafin and secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor attenuates NF-kappa B-dependent inflammatory responses of human endothelial cells and macrophages to atherogenic stimuli. J Immunol. 2004;172:4535–4544. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sano C, Shimizu T, Sato K, Kawauchi H, Tomioka H. Effects of secretory leucocyte protease inhibitor on the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-10 and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta), by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121:77–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Bergen BH, Andriessen MP, Spruijt KI, van de Kerkhof PC, Schalkwijk J. Expression of SKALP/elafin during wound healing in human skin. Arch Dermatol Res. 1996;288:458–462. doi: 10.1007/BF02505235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Margulieux KR, Fox JW, Nakamoto RK, Hughes MA. CXCL10 Acts as a Bifunctional Antimicrobial Molecule against Bacillus anthracis. MBio. 2016;7 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00334-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cole AM, et al. Cutting edge: IFN-inducible ELR- CXC chemokines display defensin-like antimicrobial activity. J Immunol. 2001;167:623–627. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dai C, et al. CXCL14 displays antimicrobial activity against respiratory tract bacteria and contributes to clearance of Streptococcus pneumoniae pulmonary infection. J Immunol. 2015;194:5980–5989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dajani R, et al. Lysozyme secretion by submucosal glands protects the airway from bacterial infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:548–552. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0059OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Akinbi HT, Epaud R, Bhatt H, Weaver TE. Bacterial killing is enhanced by expression of lysozyme in the lungs of transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2000;165:5760–5766. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.T ER, J GT. Killing of Gram-negative Bacteria by Lactoferrin and Lysozyme. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1991;88:1080–1091. doi: 10.1172/JCI115407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Flo TH, et al. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature. 2004;432:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chan YR, et al. Lipocalin 2 is required for pulmonary host defense against Klebsiella infection. J Immunol. 2009;182:4947–4956. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803282. doi:182/8/4947 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Aujla SJ, et al. IL-22 mediates mucosal host defense against Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Nat Med. 2008;14:275–281. doi: 10.1038/nm1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Crouch EC. Collectins and pulmonary host defense. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:177–201. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.LeVine AM, Whitsett JA. Pulmonary collectins and innate host defense of the lung. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:161–166. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu H, et al. Surfactant proteins A and D inhibit the growth of Gram-negative bacteria by increasing membrane permeability. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1589–1602. doi: 10.1172/JCI16889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thaikoottathil J, Chu HW. MAPK/AP-1 activation mediates TLR2 agonist-induced SPLUNC1 expression in human lung epithelial cells. Mol Immunol. 2011;49:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bingle CD, Gorr SU. Host defense in oral and airway epithelia: chromosome 20 contributes a new protein family. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2144–2152. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.002. S1357272504001864 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu Y, et al. Increased susceptibility to pulmonary Pseudomonas infection in Splunc1 knockout mice. J Immunol. 2013;191:4259–4268. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Liu Y, et al. SPLUNC1/BPIFA1 contributes to pulmonary host defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae respiratory infection. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1519–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fischer H. Mechanisms and function of DUOX in epithelia of the lung. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2453–2465. doi: 10.1089/ARS.2009.2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Forteza R, Salathe M, Miot F, Conner GE. Regulated hydrogen peroxide production by Duox in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:462–469. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0302OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pezzulo AA, et al. Reduced airway surface pH impairs bacterial killing in the porcine cystic fibrosis lung. Nature. 2012;487:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature11130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chandler JD, Day BJ. Biochemical mechanisms and therapeutic potential of pseudohalide thiocyanate in human health. Free Radic Res. 2015;49:695–710. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2014.1003372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hammad H, et al. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Allakhverdi Z, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin is released by human epithelial cells in response to microbes, trauma, or inflammation and potently activates mast cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:253–258. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Llop-Guevara A, et al. A GM-CSF/IL-33 pathway facilitates allergic airway responses to sub-threshold house dust mite exposure. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.O'Grady SM, et al. ATP release and Ca2+ signalling by human bronchial epithelial cells following Alternaria aeroallergen exposure. J Physiol. 2013;591:4595–4609. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.254649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kool M, et al. An unexpected role for uric acid as an inducer of T helper 2 cell immunity to inhaled antigens and inflammatory mediator of allergic asthma. Immunity. 2011;34:527–540. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dulek DE, et al. Allergic airway inflammation decreases lung bacterial burden following acute Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in a neutrophil- and CCL8-dependent manner. Infect Immun. 2014;82:3723–3739. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00035-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sharma M, Sharma S, Roy S, Varma S, Bose M. Pulmonary epithelial cells are a source of interferon-gamma in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:229–237. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Murdock BJ, Huffnagle GB, Olszewski MA, Osterholzer JJ. Interleukin-17A enhances host defense against cryptococcal lung infection through effects mediated by leukocyte recruitment, activation, and gamma interferon production. Infect Immun. 2014;82:937–948. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01477-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lee HS, et al. IL-23 secreted by bronchial epithelial cells contributes to allergic sensitization in asthma model: role of IL-23 secreted by bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;312:L13–L21. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00114.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Spolski R, Leonard WJ. Interleukin-21: a double-edged sword with therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:379–395. doi: 10.1038/nrd4296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Di Stefano A, et al. T helper type 17-related cytokine expression is increased in the bronchial mucosa of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157:316–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ouyang W, Kolls JK, Zheng Y. The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity. 2008;28:454–467. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Schneider DS, Ayres JS. Two ways to survive infection: what resistance and tolerance can teach us about treating infectious diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:889–895. doi: 10.1038/nri2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Westphalen K, et al. Sessile alveolar macrophages communicate with alveolar epithelium to modulate immunity. Nature. 2014;506:503–506. doi: 10.1038/nature12902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Koga T, et al. TNF-alpha induces MUC1 gene transcription in lung epithelial cells: its signaling pathway and biological implication. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L693–701. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00491.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ueno K, et al. MUC1 mucin is a negative regulator of toll-like receptor signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:263–268. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0336RC. doi:2007-0336RC [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kim KC, Lillehoj EP. MUC1 mucin: a peacemaker in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:644–647. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0169TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lu W, et al. Cutting edge: enhanced pulmonary clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by Muc1 knockout mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:3890–3894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sawa T, et al. Evaluation of antimicrobial and lipopolysaccharide-neutralizing effects of a synthetic CAP18 fragment against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a mouse model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3269–3275. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tecle T, White MR, Gantz D, Crouch EC, Hartshorn KL. Human neutrophil defensins increase neutrophil uptake of influenza A virus and bacteria and modify virus-induced respiratory burst responses. J Immunol. 2007;178:8046–8052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Uddin M, Levy BD. Resolvins: natural agonists for resolution of pulmonary inflammation. Prog Lipid Res. 2011;50:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Levy BD, Serhan CN. Resolution of acute inflammation in the lung. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:467–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]