Abstract

Introduction

Near-infrared ray (NIR)-responsive “smart” nanoagents allow spatial and temporal control over the drug delivery process, noninvasively, without affecting healthy tissues and therefore they possess high potential for on-demand, targeted drug/gene delivery. Various NIR-responsive drug/gene delivery techniques are under investigation for peripheral disorders (especially for cancer). Nonetheless, their potential not been extensively examined for brain biomedical application.

Areas Covered

This review focuses on NIR-responsive characteristics of different NIR-nanobiophotonics-based nanoagents and associated drug delivery strategies. Together with their ongoing applications for peripheral drug delivery, we have highlighted the opportunities, challenges and possible solutions of NIR-nanobiophotonics for potential brain drug delivery.

Expert Opinion

NIR-nanobiophotonics can be considered superior among all photo-controlled drug/gene delivery approaches. Future work should focus on coupling NIR with biocompatible nanocarriers to determine the physiological compatibility of this approach. Their applications should be extended beyond the peripheral body region to brain region. Transient or intermittent NIR exposure strategies may be more accommodating for brain physiological ambience in order to minimize or avoid the possible deleterious thermal effect. In addition, while most studies are centered around the first NIR spectral window (700–1000 nm), the potential of second (1100–1350 nm) and third (1600–1870 nm) windows must be explored.

Keywords: Near infrared ray (NIR), nanoparticles, biophotonics, drug delivery, cancer, brain, and neuro-disorders

1. Introduction

Last six decades have been the years of the modern day drug delivery technology. The initial half of this period i.e. first generation witnessed multitude of successful oral and transdermal controlled release formulations for clinical use. The focus of these technologies was to control the physicochemical properties of delivery systems. Their primary mechanisms were based on dissolution, diffusion, osmosis, or ion-exchange properties. The second half or generation of the modern day drug delivery technology have not been equally successful. By this time focus had shifted to solve the inability of drug carriers to overcome various biological barriers which was of little or no priority during the first generation. This led to the development of various “smart” drug delivery systems with aim to achieve zero-order release formulation, sustained release parenteral-implanted formulation, and nanodrug carriers [1]. The conceptual depiction of zero-order and sustained release formulations are represented in Figure 1. Most of these technologies, so far, have made little progress to achieve an adequate “in-vitro::in-vivo” correlation and as such their applicability have not grown beyond pre-clinical experiments. This can be attributed to less-understood biological barriers (e.g. drug precipitation in blood, adhesion and adsorption of cellular and blood components to drug carriers, toxicity level, biodistribution through altering vascular extravasation, renal clearance, metabolism pattern, properties of endothelial barriers, disease microenvironment, etc.) which are unpredictable as well [2]. Thus, next or 3rd generation drug delivery technology must have ability to establish the homeostatic balance between physicochemical functional properties of formulations and biological barriers. A right first-step in this direction can be achieved by accommodating and modifying existing “smart” drug delivery technology to overcome functional barriers such as control of drug solubility, control on loading and release kinetics, control of therapeutic period, and control of carrier size, shape, functionality, surface chemistry, flexibility, signal specificity, stimuli sensitivity, etc. This may allow us to achieve targeted and/or self-regulated drug delivery technology for both small and large drug molecules [1].

Figure 1.

Bioavailability of drug molecule is function of time: Conceptual depiction of zero-order and sustained release formulations in compare to conventional drug delivery strategies.

Advances in nanotechnology, biotechnology, and materials sciences have led to develop various “smart” nanodrug delivery systems. These systems can react to specific stimuli in a predictable and specific way to allow spatial and temporal control over the drug delivery process. Nanoscale drug-delivery technology possess various advantages over other conventional and contemporary approaches, details of which are beyond scope of this review and have been described elsewhere [3]. Major nanoparticle based drug delivery systems are: a) polymeric and polymer nanofibers, b) dendrimers, c) micelles, d) liposomes, e) solid lipid nanoparticles, f) lipid nanocapsules and nano-emulsions, g) magnetic nanoparticles, h) gold nanoparticles, i) silver nanoparticles, j) aptamers, k) carbon nanotubes, l) graphene oxide nanoparticles, m) upconversion nanocarriers, n) nano-gels, and o) cell-based nanocarriers. These nano-systems have been engineered in one way or the other for their responsiveness to external or internal stimuli that can be physical, chemical, and/or biological. Biological-responsive nanocarriers have been inspired by existence of pathology/tissue-specific biomolecules such as ATP, ROS, glucose, Ca2+, protein, DNA, miRNA, hydrolases, oxidoreductases, and other enzyme systems. Chemical-responsive nanocarriers are largely tailored to react in different pH and redox conditions of specific tissues and cellular organelles such as lysosomes, endosomes, golgi apparatus and cytosol. Biological and chemical stimuli can also be categorize as the internal stimuli. Physical-responsive nanocarriers are designed to react in response to external exposure of magnetic field, electric field, ultrasound, mechanical pressure/stress, temperature, and light irradiation. In some cases intrinsic hyperthermic nature of pathological sites are also exploited for thermos-responsive drug delivery carriers [4,5]. Details of different stimuli-responses for nanocarriers are compared in table 1.

Table 1.

A comparison of various stimuli-responsive nanocarriers [4, 5]: Most of these systems are in laboratoy-based preclinical stages for targeted drug delivery and more rigorous research-homework (particularly in vivo) has to be elucidated to sort out various associated shortcomings.

| Nanocarrier types | Mechanisms | Current research standings and major technical limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Thermoresponsive | ✓ Nonlinear sharp change in physical properties of component(s) of nanocarrier materials due to temperature. | ✓ Phase I and Phase II Clinical trial: based on temperature sensitive liposomes. ✓ Other materials such as polymers based findings are limited to in vivo study. |

| Magnetic-responsive | ✓ Magnetic field generates torque and magnetic pulse in the MNPs so that layers of external encapsulation material of carrier are disturbed and distorted. | ✓ Phase I, II, and III Clinical trial: based on Iron oxide magnetite. ✓ Phase I and II Clinical trial: based on iron and carbon particles. ✓ European Union regulatory approval: Based on magnetic fluid. ✓ Magnetic guidance is hampered by the complexity involved in the set-up of external magnetic fields, which need adequate focusing with sufficient strength and deep penetration into tissues to reach diseased area. |

| Ultrasound-triggered | ✓ Tuning of frequency, duty cycles and time of exposure of ultrasound waves create cavitation phenomena or radiation forces which modulate nanocarriers’ physical properties. | ✓ Preclinical: In vitro and in vivo studies show controlled drug delivery and enhancement of vessel permeability. ✓ Ultrasound is strongly attenuated by bone. ✓ Possess genotoxic potential because of its ability to damage DNA. |

| Electroresponsive | ✓ Electric-field driven movement of charged molecules. ✓ Alternating current field induces dipole moment which disturbs the nanocarrier charge symmetry and subsequently ionic bond between drug and carrier is broken. |

✓ Preclinical: In vitro and in vivo studies show targeted and controlled drug delivery. ✓ Low tissue penetration depth of electric field. ✓ Way to avoid undesired tissue damage needed to be discovered. |

| Light-triggered | ✓ Photosensitiveness-induced structural modifications of nanocarriers. | ✓ Preclinical: In vitro and in vivo studies show targeted and controlled drug delivery. ✓ UV-visible lights have limited accessibility into tissue depth due to their absorption by cellular chromophores such as lipids, water, and hemoglobin. ✓ Photothermal damage upon exposure has limited this approach to cancer targeting or for certain peripheral purpose. ✓ Potential of second (1100–1350 nm) and third (1600–1870 nm) NIR window must be explored. ✓ Discovering biocompatible material(s) that can show efficient NIR absorption and photo-responsiveness even during the transient NIR exposure will take this approach forward. |

| Mechanical-responsive | ✓ Disassembly of mechanoresponsive molecules /structures of nanocarriers due to applied pressure, shear stress, or other physical stimuli cause volumetric variation. | ✓ Preclinical: only few studies are available and hence it requires more extensive analysis. |

| pH-sensitive | ✓ Ionizable groups of nanocarriers undergo conformational and/or solubility changes in response to environmental pH variation. ✓ Acid-sensitive bond’s cleavage enables release of anchored molecules. ✓ Modifications of nanocarrier’s charge upon pH change. |

✓ Preclinical: In vitro and in vivo studies show targeted and controlled drug delivery. ✓ Nanocarrier is usually tuned to respond against a specific pH. However, pH conditions in body are non-homogenously varying in tissue/organ specific manner. Thus carrier may encounter release-specific conditions before it reaches to target resulting in immature viability of carrier in physiological conditions. |

| Redox-sensitive | ✓ Disulphide bonds, prone to rapid cleavage by glutathione (GSH), are used to attain redox sensitivity. ✓ Cytosolic trigger of drug release due to differences in GSH concentrations in extracellular and intracellular compartments and in tumor tissues. |

✓ Preclinical: In vitro and in vivo studies show targeted and controlled drug delivery. ✓ Similar to non-homogenous pH conditions throughout body, drug-release control by a specific redox molecular mechanism in a complex biological environment will require numerous trials and errors to achieve compatibility according to physiological viability. |

| Enzyme-sensitive | ✓ Pathological condition specific altered expression of enzymes (such as proteases, phospoholipases or glycosidases) cause change in the chemical structure of enzyme-responsive components of nanocarriers. | ✓ Preclinical: In vitro and in vivo studies show targeted and controlled drug delivery. ✓ Again complexity of biological environment is the determining factor where optimum enzyme activity is highly variable in physiological conditions in compare to experimental one. ✓ Low resistance of nanocarriers to enzyme attack is often observed. |

| Biomolecular-responsive | ✓ Pathological/diseased condition specific expression of biomolecules (such as glucose, ATP, DNA, and ROS) cause change in the chemical structure of nanocarriers made up of biomolecule-responsive materials. | ✓ Preclinical: In vitro and in vivo studies show targeted and controlled drug delivery. ✓ Similar to other biological stimuli, complexity of biological environment is the determining factor. ✓ Strong clinical evidence of the feasibility of delivery system has not yet been achieved. |

| Multistimuli-responsive | ✓ Nanocarriers are designed to be sensitive to more than one aforementioned stimulus. | ✓ Preclinical: Too complicated and still remain as proofs of concept only. ✓ To determine the viability of these strategies, evidences of regulation of response to each stimulus would be needed in both in vitro and in vivo conditions. |

Light-sensitive nanoagents have received significant interest in biological and medical research in recent years. The field has been named as “nanobiophotonics” and can be useful to achieve bio-imaging, sensing, therapy, gene delivery, and on-demand drug delivery in unique way [6]. Because most nanomaterials are sensitive to UV (10–400 nm) and visible (400–700 nm) spectra, many of initial nanobiophotonics research for drug/gene delivery or other therapeutical purposes explored these light ranges only [5,7]. Lately, NIR lights have been focus of nanobiophotonics research due to disadvantages of UV-visible light. Far-UV light (< 200 nm) are hazardous to cell and tissue and possess threat of photodestruction of active molecules such as DNAs and proteins. Other UV lights are also much more cytotoxic in compare to light spectrum of other regions. Although continuous wave long-UV lights (200–400 nm) have little or no effect on the intactness of tissue; all UV-visible lights have limited accessibility into tissue depth due to their absorption by cellular chromophores such as lipids, water, and hemoglobin. Photon’s scattering of UV-visible light by tissue also contribute significantly to prevent them from deeper penetration. In contrast, lights in the NIR region can transmit deep into the tissue (up to 10 cm) due to their low total extinction coefficient during NIR exposure i.e. NIR lights have lower energy per photon and therefore low absorption and scattering in tissue. In fact, cellular chromophores barely absorb NIR and NIR exposure cause little to zero tissue damage [5–10]. Thus, NIR-nanobiophotonics provide unique advantage in utilizing non-ionizing radiation for noninvasive tissue penetration for various therapeutical purposes including for gene/drug delivery.

2. Features of NIR-Nanosystems

Materials at their nanosized structure range acquire remarkable potential for their use as theranostic agent. In this context, feasibility of NIR-nanobiophotonics is interdependent on structural, biological, and optical characteristics of associated nanocarriers and their components. Nanostructures possess higher specific area and these features are ideal for maximizing delivery of drug molecules and/or imaging agents [11]. While increased specific area is useful for higher drug loading or ligand decoration, internal volume performs dual functions in molecule encapsulation and their protection against chemical or enzymatic degradation in peripheral circulation [3,12]. Nanocarriers tethered with target specific ligands are adequately small to interact with cell/tissue specific receptors to achieve active targeting for direct delivery of drugs into an affected organ or tissue [12]. Another important characteristic of nanocarriers is their ability to avoid reticuloendothelial system. Reticuloendothelial clearance is the function of nanocarrier’s size and their surface characteristics [13]. In contrast to conventional oral drug carriers, oral uptake of nanocarriers of <100 nm escape portal blood circulation route and pass to systemic circulation via intestinal lymphatic transport. This results in remarkable reduction of first pass hepatic metabolism and drug’s bioavailability in circulation is increased in terms of both quantity and time [3]. These features make nanocarriers compatible for passive targeting as well. For example, enhanced permeability and retention effect is highly successful in targeting tumors and HIV infections of enterohepatic circuit and lymph nodes, respectively [14]. When injected intravenously, nanocarrier’s clearance from the bloodstream can be reduced by various coating approaches which provide stealthiness to the nanosystems by altering their surface charge and hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity [13]. Surface coating with positively charged materials enhance their binding with cellular surface which are naturally negatively charged. Coatings with hydrophilic compounds such as polyethylene glycol, pluronics, etc. prevent nanocarrier’s opsonization resulting in their increased blood circulation duration. Surface coated nanocarriers can freely flow into capillaries to travel across various physiological barriers such as blood-brain barrier, stomach epithelial, etc. via transcellular and/or paracellular mechanisms. Surface charge distribution and hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity is also vital (other than size) for drug loading, especially when drug is hydrophobic in nature. Also, spontaneous reticuloendothelial uptake of nanocarriers by inflammatory-response cells such as macrophage has led to development of cell-based nanosystems where nanocarriers loaded macrophages serve as natural drug carriers to the target due to their intrinsic ability to migrate toward zones of inflammation [3,15,16].

While drug loading is one aspect of nanocarriers, nanomaterial’s characteristics greatly influence the drug release kinetics as well. Tunability of surface charge, hydrophobicity, crystallinity, etc. in response to internal or external factors influences the pattern of drug release. Cell-specific internal mechanisms such as Ca2+ concentrations, exocytosis of drug containing intracellular vesicles, pathology specific changes in temperature, pH, etc. are putatively believed to be primary reasons of disturbing drug’s bonding from nanocarriers [17]. Since these cellular phenomenon are uncontrollable, the “when and how” aspects of drug release are not defined. Hydrophobic and hydrophilic coatings respectively prolong the drug release process and reduce dose frequency of poorly soluble drugs. Crystallinity determines the molecular composition of material’s dissolution such that degradation of the amorphous regions are faster than the crystalline region which, respectively, result subsequent fast and slow release of associated drugs. Similarly, higher specific area of nanocarriers enable higher drug loading which, unlike one-time burst release from conventional carriers, result in initial burst release and subsequent slow release at constant rate for certain duration [3]. While nanomaterials certainly improve the release kinetics and minimize dose frequency in compare to conventional methods, a more pragmatic approach will be manually controllable mechanism for spatial and temporal control of drug release to exert desirable therapeutical effect as and when required. This can be achieved by several means where, tuning of nanocarrier’s physical properties such as magnetic, electrical, thermal, optical, etc. by an exterior, non-invasive source break away the bound drugs from nanocarriers [18]. In recent years, modulation of nanocarrier’s optical property has shown significant potential for the externally controlled, on demand drug release purpose. Optical characteristics, in general, are strongly dictated by particle size and therefore nanomaterials have improved optical properties than their macroscopic structures. Behavior of electrons in the nanometric confinement dictate phenomenon such as localized surface plasmon resonance, delocalized electron arrangements, anti-stokes fluorescence light emission ability, etc. that enable nanomaterials to absorb and emit lights in different wavelengths ranging from UV-Visible to near infrared [19,20]. These have led to inventing several types of nanodrug carrier composites possessing optical-signal mediated controlled release ability.

Overall, biological and structural features of nanocarriers are complementary to each-other in achieving active and/or passive targeting and avoiding their clearance by peripheral entrapments such as reticuloendothelial system, renal system, etc. Structural features help in modulating drug release kinetics as well. Physical features such as optical tunability of nanocarriers facilitate to achieve controlled, on-demand release.

3. NIR-nanobiophotonics for nanodrug delivery

NIR region light of 700–1000 nm wavelength, referred as transparency “therapeutic window” [10], have been experimented for several biological applications. NIR irradiation can cause various physical and chemical effects and can be irradiated from femtoseconds to several minutes as per the necessity. This section of the review is focused on the two aspects: a) mechanisms of NIR-nanobiophotonics controlled drug delivery, and b) NIR responsive drug delivery carriers.

3.1. Mechanisms of NIR-nanobiophotonics controlled drug delivery

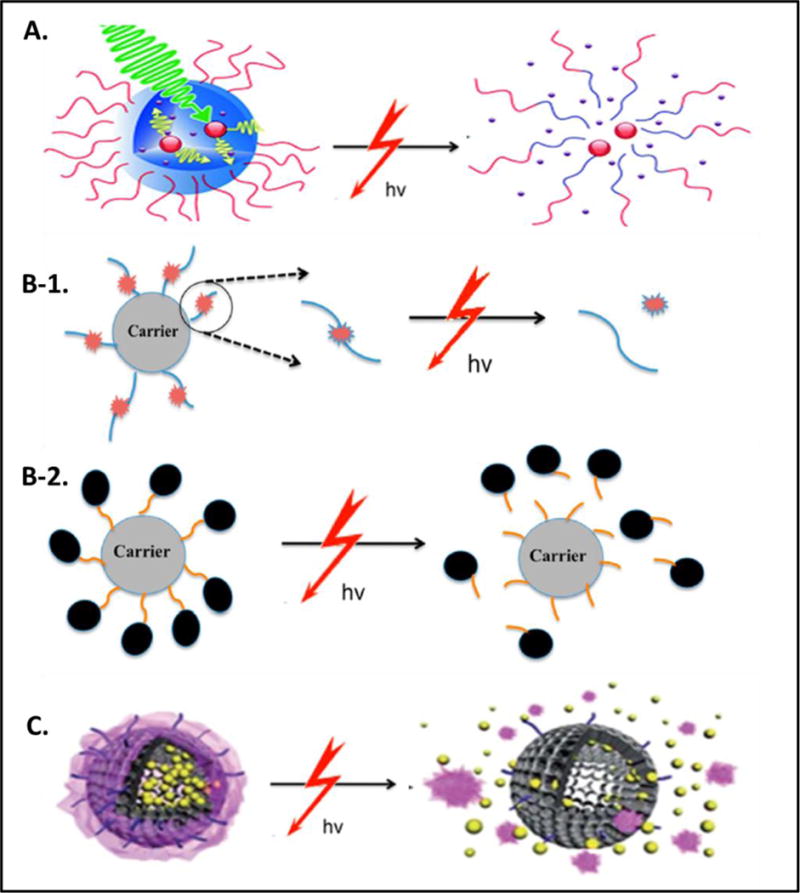

Dependent upon the composition of nanocarriers, NIR-responsive drug delivery can be achieved by three strategies: a) Self-disruption of nanocarriers in response to NIR exposure, b) Disruption of NIR-labile caging bonds, and c) Unlocking of NIR responsive “gate-keepers” caging. Figure 2 provide schematic representation of different NIR-nanobiophotonics medicated controlled drug delivery mechanisms.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustrations of mechanisms of NIR-nanobiophotonics controlled drug delivery: A) Self-disruption of nanocarriers is achieved when NIR irradiation triggers dissociation or disintegration of photo/thermolabile micelles, hydrogels, liposomes, polymers etc. [10]. B) Cleavage of NIR-labile caging bonds between photolinkers and drugs (B-1) or between carriers and photolinkers bound drugs (B-2) releases drug molecules in active form in response to NIR exposure [7]. C) Unlocking of NIR responsive “gate-keepers” caging is achieved when NIR exposure cause degradation/disruption of gating materials such as copolymer, mesoporous silica etc. which is assembled on nano-containers or scaffold loaded with drug molecules [10]. All of these NIR biophotonic mechanisms result in targeted drug delivery and controlled release in one or other way. Reproduced/Reprinted with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry (Fig. 2A and 2C; ref# 10) and from The American Chemical Society (Fig. 2B; ref# 7).

3.1.1. Self-disruption of nanocarriers upon NIR exposure

This is the most direct NIR-responsive drug delivery strategy where nanocarriers are themselves NIR-responsive. These nanocarriers innately possess high molecular extinction co-efficient or two-photon cross-section which make them capable to absorb NIR light. NIR irradiation induces remarkable physical change in these nanocarriers and subsequently they disintegrate resulting in release of bound drugs. An ideal nanocarrier in this category should have high photochemical efficiency to induce drug release with minimum NIR dose. Physical stability of nanocarriers should be intact under biological conditions and coupling of NIR irradiation should not cause deleterious effects in the biological systems [7,10]. Nanocarriers such as micelles, hydrogels, liposomes, and upconversion nanoparticles alone or in combinations have been engineered for NIR responsive drug delivery and their application have been detailed in the section 2.2.

3.1.2. Disruption of NIR-labile caging bonds

This is one of the two indirect NIR-responsive drug delivery strategies. In this case, nanocarriers are engineered in such way that NIR-photolabile caging molecules are structured on the periphery to serve as the linker elements for drug binding. The caging-bond moieties of photolabile linker molecules are modified to temporarily inactivate the drug molecule by binding/blocking to their main functional groups such as amino, hydroxyl, phosphate, and carboxyl groups. The covalently-linked caged drugs are released in response to NIR irradiation due to cleavage of caging molecules and thus control over drug release is achieved. Similar to the above case, NIR-labile caging molecules are either two-photon-sensitive or possess upconversion excitation [7,10]. While most research on this strategy utilize UV or visible light, few recent studies based on magnetic nanoparticles and upconversion nanoparticles (section 3.2.) have been engineered for the disruption of NIR-labile caging bonds.

3.1.3. Unlocking of NIR responsive “gate-keepers” caging

This caging based strategy is getting more popularity due to its unique control on the drug delivery and release process. Primarily, carriers are composed of a hollow or mesoporous inorganic nano-container/scaffold for drug loading and NIR-photolabile caging molecules to serve as the “gate-keepers” of container openings. Upon NIR irradiation, the covalently anchored “gate-keeper” molecules can undergo reversible or irreversible physicochemical changes such as translocation, controlled molecular transportation, or reversible mass movement. Utilizing these switchable characteristics of “gate-keeper” molecules, on-demand release of loaded drugs in container – as and when required – can be achieved. Nanomaterials for scafold/containers may be silica nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles, magnetic nanoparticles, upconversion nanopaticles, etc. The “gate-keeper” molecules can be polymers such as azobenzene, ruthenium complex, etc. This strategy promise to have better feasibility than above two in terms of controlled morphology and monodispersity of nanocarriers, high drug loading ability, prevention of drug leaching, protection from clearance or entrapment by reticuloendothelial systems, and protection from unwanted drug decompositon due to metabolic (enzymztic mainly) activity of peripheral circulation or tissue enzymes [7,10].

3.2. NIR responsive drug delivery carriers

Several types of nanocarriers have been engineered to comply with aforementioned mechanisms and they have been shown to exert controlled drug delivery in response to NIR exposure (Figure 3). These nanocarriers, in large, have been explored for the delivery of anti-cancer agents. This section of the review is focused on the physicochemical characteristics of different NIR-responsive nanocarriers and their in vitro and in vivo applications to date.

Figure 3.

Illustration of major nanocarriers used for NIR biophotonics mediated drug delivery to targeted area under the influence of NIR irradiation [8]. Reproduced/Reprinted with permission from The John Wiley and Sons.

3.2.1. Gold Nanocarriers

Gold (Au) nanocarriers (AuNCs) exhibit strong localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) i.e. irradiation of NIR or other external lights induce collective oscillation/excitation of surface electrons. This provides AuNCs capability to absorb NIR light and, in turn, offer suitability for imaging agent and NIR-responsive drug delivery carrier. The LSPR oscillation phenomenon is size and shape dependent. Electronic oscillation in rod shaped AuNCs perform both a longitudinal and a transverse oscillation pattern in compare to one way oscillation in round particles. Thus, absorption intensity of NIR light varies in different AuNCs forms with nanorods possessing high NIR absorption than nanoparticles and nanoshells. The optico-responsiveness of AuNCs can be enhanced by surface coatings of polymers, peptides, and other surfactants [21,22]. Surfactant coatings also improve the facile conjugation characteristics of AuNCs to load various therapeutics molecules such as drugs, siRNAs, miRNAs, DNAs, antibodies, etc. These molecules can be released in response to NIR irradiation. Shen et al. developed mesoporous silica-encapsulated gold nanorods for NIR-triggered release of anti-cancerous drug, doxorubicin, in the A549 cell culture model and tumor-bearing mice as well. The 808 nm NIR laser with power intensity of 3 W/cm2 successfully ablated cancer as a result of combined effect of photothermal treatment and drug delivery [23]. In other study, mesoporous silica coated gold nanorods showed accelerated release of doxorubicin with efficacious anti-cancerous effect on A549 cells due to 250mW 780nm NIR irradiation [24]. Agarwal et al. designed a thermosensitive liposome which in combination with PEGylated gold nanorods could deliver and release doxorubicin in response to 810 nm NIR laser with power intensity of 0.5 W/cm2. Both U87 MG cell based in vitro system and glioma cell bearing nude mice showed significant positive impact as determined by tumor-site apoptosis assay [25]. A hybrid delivery system of hollow gold nanoshell and liposome showed similar drug delivery potential because NIR irradiation caused release of liposome from this nanocarrier within seconds of exposure [26]. Similarly, release of polyethylene glycol was achieved from gold nanorods due to the retro Diels-alder reaction in response to NIR induced photothermal effect [27]. Ma et al. conjugated succinyl silane nanomicells with magnetic nanoparticles and gold nanoshells to achieve magnetic-field guided drug delivery and gold based photothermal effect in the same nanocarrier system. This carrier showed NIR-triggered stepwise release of doxorubicin [28]. A thermally responsive hydrogel coated gold-silica nanoshell was designed by Strong and West where gel remain swollen even under physiological conditions. This provided nanocarriers a unique ability to expel large amount of water and doxorubicin in response to 808 nm NIR exposure (4 W/cm2). Higher drug intake was achieved when this nanocarrier treated colon carcinoma cells were exposed to NIR irradiation [29]. Ko et al. developed a polymer-gold nanorod conjugate which, in response to 808nm NIR irradiation at the fluence of 2Wcm−2 for 10 minutes, triggered release of bound doxorubicin. In fact, in vitro cell study showed selective regulation of doxorubicin release in response to NIR irradiation [30]. A novel gold nanocage system suitable for NIR based metal enhanced fluorescence was designed by Camposeo et al. and this system can be integrated with the hollow interior and controllable surface porosity to develop a targeted drug delivery system with fluorophore based diagnostic ability [31]. Ren and chow prepared NIR-sensitive Au-Au2S nanoparticles and showed release of anti-tumor drug, cis-platin, in response to 1064 nm NIR irradiation [32]. NIR responsive gold nanocarriers can be equally efficacious in providing therapeutical benefit to peripheral diseases other than tumors. A subcutaneous implant system based on hybrid matrices of gold nanorods and liquid crystalline achieved on-demand drug release with two different rates in response to irradiation of 810 nm NIR light (506 mW/cm) [33]. In a classic display of unlocking of NIR responsive “gate-keepers” caging system, Timko et al. developed an implantable gold nanoshells based “gate-keepers” caging system with thermosensitive copolymer nanogel capping. The permeability of this nanogel-based nanocomposite membrane could be modulated for drug release by irradiating 808-nm diode laser of 0–2.5W continuous wave output in diabetic rat model [34]. A nanocarrier made up of gold nanorod core and mesoporous silica shell with reversible single-stranded DNAs valve as their cap showed NIR laser based controlled release of doxorubicin [35]. Similarly, Gold nanocage covered by smart polymers showed controlled drug release in response to NIR irradiation [36]. Hollow gold nanoparticles developed by Park et al. released doxorubicin upon NIR trigger [37]. Pissuwan et al. showed enhanced transdermal protein delivery upon NIR exposure when a solid-in-oil dispersion system was combined with gold nanorods [38]. Similarly, Nose et al. showed higher insulin delivery in stratum corneum [39]. NIR responsive gold nanocarriers have been successful for gene delivery as well. Yamashita et al. showed controlled release of single-stranded DNA in tumors of mice upon NIR irradiation on the double-stranded DNA-modified gold nanorods [40]. Conjugates DNA and gold nanorod was utilized for targeted release of cancer- targeting aptamer in response to NIR irradiation [41]. Similarly, release of green fluorescent protein coded plasmid from gold nanorods was achieved in response to NIR irradiation [42]. In a recent study, Zhang et al. designed a smart nanocarrier consisting of gold nanorods, thermosensitive polymers, and DNA Y-motifs to direct NIR mediated controlled co-release of siRNA and Doxorubicin in in vivo system [43]. These gene delivery approaches can be extended to siRNAs, miRNAs and other gene types.

3.2.2. Carbon Nanotube carriers

Primarily, rolling up of graphene sheet yield carbon nanotubes which can be categorized as single-walled and multiwalled based on only one and more than one “one-inside-the-other” seamless stacking of cylindrical arrangements, respectively. Single-walled nanotubes (SWNTs) have been focus of various biomedical applications. The SWNTs possess high absorbance in the NIR light region due to their electronic transitions between the first and second van hove singularities and therefore it can be a model nanocarrier for NIR-responsive drug delivery [44]. Nonetheless, insolubility of SWNTs in aqueous solvent for physiological compatibility and toxicity is debatable among scientific fraternity. Similar to gold nanocarriers, NIR-responsive drug delivery applications of SWNTs have been focused on cancer treatment. A nanoformulation of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) conjugated doxorubicin on SWNTs showed burst drug release within seconds of low power (1mW/cm2) 800nm NIR irradiation in in vitro cancer cell model [45]. Similarly, PEG modified mesoporous silica coat on SWNTs showed NIR (808 nm laser; 0.7 W/cm2) triggered release of doxorubicin which synergized the photothermal mediated cancer cell killing in both in vitro and in vivo system. [46]. A tumor-specific nanoformulation consisting of anti-cancer drug, tumor targeting peptide (NGR), and SWNT showed promise of NIR stimulated drug release upon irradiation with 808nm laser at a power density of 1.4 W/cm2 [47,48]. Using the same NIR wavelength and intensity Kam et al. showed release of DNA cargo from DNA functionalized SWNTs [44]. The DNA-SWNTs conjugates have been utilized for NIR mediated release of cancer- targeting aptamer [41]. Zhou et al. utilized DNA’s ability to solubilize SWNTs by π-π interactions and applied 808nm NIR irradiation at 3W/cm2 power intensity to study antitumor effect of immunostimulatory “CpG DNA-SWNTs” conjugate in colon 26 cells bearing tumor mice [49]. In a simulation based study, it was predicted that polar drugs loaded in CNTs can be released by diffusion upon NIR irradiation [50]. Sada et al. showed potential of CNTs in manipulating plasma membrane when exposed with nanoseconds NIR irradiation and this can be utilized for targeted drug delivery as well [51]. Utilizing a similar concept, crystalline magnetic carbon nanoparticles were used to deliver impermeable dyes and plasmids into cells upon irradiation of a very low power continuous wave NIR beam [52]. NIR responsive drug delivery and release from multiwalled carbon nanotubes have also been shown for cancer treatment [53–55]. Additionally, hybrid of CNTs with other nanocarriers such as gold particles can be an efficient NIR-responsive drug delivery carrier [56] and these should be explored further for gene/drug delivery of diseases other than cancer.

3.2.3. Graphene oxide nanocarriers

Graphene oxide (GO) possess heterogeneous chemical and electronic structures. Electronically GO is a hybrid material composed of both conducting π-states from its sp2 carbon sites and carrier transporting gap between the σ-states of its sp3-bonded carbons. Chemically, different types of oxygen-containing functional groups such as carboxylic acid, epoxide, ketonic, and hydroxide are available on its basal plane and edge which can interact ionically, covalently and/or non-covalently with various organic and nonorganic materials. Owing to this tunability in functional groups of GO and their hexagonal carbon ring it is possible to synthesize unique functional hybrid and composite materials to achieve physiological stability and they can be used for several biomedical applications [8,57]. Similar to CNTs, NIR absorbance of GO is due to its delocalized electron arrangements. Nonetheless, unlike CNTs, GO has excellent water solubility, does not cause cytotoxicity originating from metallic catalyst impurities, and can directly bind to various drugs via π-π stacking [57,58]. Moreover, reduction and functionalization of GO alter its optoelectronic properties and improve facile conjugation characteristics. Glucose [59] and hydrazine monohydrate [60] mediated reduction of GO showed multifold higher NIR absorbance. A possible explanation of this behavior is removal of all oxygen-containing species from the region adjacent to the sheet edges which results in clean graphene patches with large electron density [60]. Similarly, PEGylation of reduced GO increases its absorbance in both visible and near infrared lights [58,61]. The higher NIR absorbance of GO and its reduced forms (with or without functional moieties) have been used for NIR-photothermal based drug delivery in cancer treatments. Kim et al. developed a PEG and branched polyethylenimine functionalized nanotemplate of reduced GO. They demonstrated that irradiation of 808 nm laser at 6 W/cm2 power density cause release of loaded doxorubicin from their nanocarrier [62]. Further this nanocomplex was utilized for enhanced gene delivery upon NIR irradiation which shows their potential for spatial and temporal site-specific gene/siRNA delivery as well [63,64]. Kurapati and Raichur engineered a layer-by-layer assembly of GO–poly (allylamine hydrochloride) composite and dextran polymer in capsular form. They demonstrated that 1064 nm NIR irradiation at power density between 30 mW to 70 mW releases encapsulated doxorubicin in controlled fashion due to point-wise opening of capsule. This technology can further be applied for on-demand delivery and release of genes and other therapeutics [65]. Shi et al. hydrothermally synthesized a nanocomposite of GO over silver particles which was loaded with doxorubicin and was subsequently functionalized with DSPE-PEG2000-NGR for cancer cell specificity. This nanoformulation showed strong dependency on 808 nm NIR laser (power density 2 W/cm2) for drug delivery [66]. Similarly, a nanocomposite of PEGylated GO and CuS showed NIR-dependent drug release when irradiated with 980 nm laser at a power density of 1 W/cm2 [67]. Wei et al. constructed nanocookies based on reduced GO co-arranged with amorphous carbon and mesoporous silica. This unique nanocookies provided burst release of anti-cancerous drug in response to 808nm NIR irradiation [68]. Further, a nanohybrid of GO and manganese ferrite triggered doxorubicin release upon irradiation with 808-nm NIR laser at a power density of 0.5 W/cm2 [69]. Tang et al. fused Cy5.5-aptamer conjugate on the assembly of GO which was prewrapped with doxorubicin loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles. While Cy5.5 was provided for nucleolin specific targeting, the mesoporous silica wrap in nanoconjugate served as gatekeeper to prevent and release doxorubicin in the absence and presence of 808 NIR, respectively [70]. Tian et al. utilized PEGylated GO for higher cellular uptake of photosensitizer Ce6 by exposing 808 nm NIR laser at a power density of 0.3 W/cm2 [71]. A GO containing hydrogel system by Fusco et al. can also be effective in developing nano-platform for on-demand, targeted therapeutic interventions [72]. Recently, some study pertaining to GO nanocarriers based drug delivery for treating brain tumors have also been experimented which is detailed in the section 2.3.

3.2.4. Upconversion nanocarriers

The unique characteristic of upconversion nanocarriers is rooted in their intrinsic anti-Stokes fluorescence light emission ability. As per conventional Stokes law, fluorescence light emitters release weaker output photon energy (emission) than their input photon energy (excitation) [73]. In contrast, upconversion materials convert absorbed single-band NIR lights into high energy photons in the bands range of UV to visible lights. Higher NIR to shorter NIR upconversion is also possible [74]. This exhibition of frequency conversion capability resides in their unique molecular orbitals where intra-4f or 4f-5d electronic transitions occur with concomitant wave functions localized within a single ion [75]. The upconversion phenomenon is mainly observed in rare earth element of trivalent lanthanide series. Details of different upconversion luminescence mechanisms can be accessed in previous reviews [73,75,76]. The upconversion nanocarriers (UCNs) for biomedical applications are engineered by doping emitter/sensitizer of lanthanide series (guest materials) on inorganic metal based matrix (host materials). Typical host lattices used for this purpose are LaF3, YF3, Y2O3, LaPO4, and NaYF4 and guest materials are Yb3+, Er3+, and/or Tm3+. While fluoresce generation ability of UCNs have been of great interest for biological imaging, several core−shell structures have been employed for concomitant drug delivery. Different drugs, antibodies and/or other ligands can be loaded on UCNs by electrostatic interactions or adsorption [8] and they can be released upon NIR irradiation. Zhang et al. used polymer coated UCNs where they showed NIR mediated controlled release of Nile Red as their model drug [77]. Yan et al. also encapsulated UCNs in block copolymer micelles. In this case, micellar dissociation via photocleavage activation of o-nitrobenzyl group was achieved by exposing 980 nm NIR light and this releases co-loaded hydrophobic species. Same research group in another study developed a nanoconjugate of photosensitive hybrid hydrogels loaded on UCNs to achieve release of proteins and enzymes due to gel-sol transition upon NIR mediated upconversion [78]. Similarly, design of 3′,5′-dialkoxybenzoin derivatives with red-shifted absorptions by Carling et al. was used for photo-controlled release of UCNs caged compounds upon 980 nm NIR [79]. Uncaging of D-luciferin and nitric oxide from UCNs due to NIR irradiation have also been shown [80,81]. A NIR mediated remotely controlled release phenomenon was achieved by encapsulating UCNs with a unique polymer which is degradable due to UV light generated during NIR mediated upconversion mechanism [82]. Oleic acid capped UCNs showed release of trans-platinum (IV) pro-drug due to upconversion phenomenon upon NIR exposure [83]. Dacona et al. grafted UCNs with a photocaged analog of doxorubicin which was released in controlled fashion in response to NIR exposure [84]. Thus, these nanocarriers possess remarkable potential for remote-controlled drug delivery using NIR laser.

Nanocarriers containing mesoporous silica coating on UCNs (MS@UCNs) have gained special interest for controlled drug delivery because it enables delivery of higher drug payload. The MS@UCNs also protects drugs from harsh physiological environment in peripheral circulation. Porous silica fibers decorated with upconversion nanocrystals showed controlled release property for loaded Ibuprofen in response to NIR irradiation [85]. Liu et al. coated UCNs with azobenzene modified mesoporous silica to achieve NIR mediated controlled release of doxorubicin [86]. Similarly, controlled release of doxorubicin was achieved with high efficiency via NIR mediated photocleavage of theo-nitrobenzyl linker-capping of MS@UCNs and it was proposed that functionalization of this nanocarrier with folic acid can allow simultaneous intracellular drug delivery and fluorescence imaging [87]. In fact, application of folate-conjugated UCNs to target cancer cells have been shown by Chien et al.[88]. Zhao et al. developed yolk-shell arrangements of UCNs and mesoporous silica to trigger controlled release of caged anticancer drug chlorambucil in both in vitro and live tissue by exposing continuous-wave 980 nm NIR light at a power density of 570mW/cm2 [89]. In a unique approach MS@UCNs grafted with ruthenium complexes showed release of loaded doxorubicin upon exposure of 974 nm NIR light at a power density of 0.35 W cm−2. In this case NIR exposure did not showed sign of overheating and photodamage [90]. Recently, Wang et al. developed a nanocomposite which contained a UCNs core, a photosensitizer-embodied silica sandwich shell, and a β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) gated mesoporous silica outmost shell with inside-load of Rhodamine B. Irradiation of 980 nm NIR on this nanocomposite lead to upconversion phenomenon with 660 nm red light emissions. This resulted in dissociation of β-CD gatekeeper to release Rhodamine B and simultaneously singlet oxygens were generated which are helpful in cancer therapeutics [91]. Chen et al. trapped a novel UCNs in biocompatible silica matrix to develop core-shell nanocarriers for photodynamic therapy. This system can also generate and release singlet oxygen upon irradiation of 980 nm laser [92]. MS@UCNs have also been used for delivery and release of caged DNAs/siRNAs [93]. Several other UCNs based drug/gene delivery nanocarrier systems have been developed which are discussed in a recent detailed review on UCNs [94].

3.2.5. Other NIR responsive nanocarriers

The growing popularity of nanobiophotonics has steadily opened the field for development of various NIR responsive nanomaterials for drug delivery. NIR-responsive hydrogels and liposomes have been developed by incorporating various metals, carbon based nanoagents, and/or upconversion nanomaterials in their matrix [95,96]. Similarly, NIR-responsive polymeric nanomaterials for on-demand drug delivery have been experimented in combination with other nanocarriers [97]. Kumar et al. synthesized a biocompatible NIR-responsive block copolymer by conjugating 6-bromo-7-hydroxycoumarin-4-ylmethyl groups into PEG-poly (L-glutamic acid). Exposure of 794 nm NIR on nanomicellar form of this material caused their disruption due to shift in the hydrophilic/hydrophobic balance and subsequently loaded paclitaxel (anticancer drug) and rifampicin (antibacterial drug) was released [98]. A similar study by Li et al. showed release of doxorubicin from polymeric micelles of block copolymers, poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylate)- block -poly(furfuryl methacrylate) in response to 805 nm NIR irradiation [99]. Nanogel developed by adamantine-conjugated copolymer, poly[poly(ethylene glycol)monomethyl ether metharcylate]-co-poly(N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide)-co-poly(N-adamantan-1-yl-2-methacrylamide) and β-cyclodextrin (β-CD)-functionalized poly(amidoamine) dendrimer was used to encapsulate indocyanine green and doxorubicin. Drug release was achieved by photothermal-induced relaxation or dissociation of nanogel upon NIR laser irradiation [100]. In a novel approach, silica-coated lanthanum hexaboride (LaB6@SiO2) nanostructures were incorporated into polycaprolactone microneedles which, upon NIR irradiation, resulted in drug release due to increased mobility of the polymer chains in response to light-to-heat transduction mediated by the LaB6 [101]. Palladium and metal chalcogenide nanoparticles have also been experimented for NIR-responsive therapy and they possess potential of on-demand drug delivery carrier [9]. Magnetic (iron oxide) nanoparticles have been extensively investigated for drug delivery purposes [3,16,19,102–108]. Nonetheless, NIR mediated drug delivery with magnetic nanocarriers have found little relevance because photoexcitation properties and charge carrier dynamics in iron oxide is not high in the NIR region. A small absorbance peak is observed at ~840 nm NIR light due to electron traps created by O2 vacancies on the tetrahedral sites of magnetic particles, however, this peak get reduced upon coating with poly (acrylic acid), polystyrene matrix, silica or beads [109]. Therefore, NIR-responsive magnetic carrier for drug delivery include composites of iron oxide with other NIR-absorbing nanomaterials such as gold and carbon nanoparticles [52,110]. Urris et al. designed PEGylated magneto-plasmonic nanoparticles for NIR responsive drug delivery [111]. Similarly, coatings of NIR-responsive liposomes, hydrogels, etc. can be combined with MNPs to achieve targeted and on-demand chemotherapy. This can be further improved by developing a transient NIR exposure strategy [19] where intrinsic photothermal, cytotoxic effect of iron oxide nanoparticles due to NIR induced non-radiated recombination [109] can be minimized [19]. NIR responsive composites of other nanocarriers such as solid lipid nanoparticles, lipid nanocapsules and lipid nano-emulsions can also be developed for the drug delivery purpose.

4. Potential of NIR-nanobiophotonics for brain drug delivery

Current treatment strategies to alleviate the damaging effect of neurological disorders are less effective, primarily due to structural and functional complexities of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The BBB possesses ultra-selective permeability of molecules from peripheral selection where > 98% of small and large drugs are unable to transmigrate across tight-junctioned endothelial cells of brain microvasculature [3]. Several nanotechnology based approaches have been attempted to getting into the brain for management for various neuro-disorders [16]. Similarly, transcranial NIR exposure have been shown effective in treating neuro-disorders [112,113]. NIR laser can penetrate 40 mm deep into human skull, meninges, and scalp upon transcranial and intraparenchymal exposure [114]. Therefore “yet-to-be-extensively-explored” status of NIR nanobiophotonics based drug delivery for brain must be driven towards its full potential. Considering high degree sophistications and interdependence of brain cell networks in driving nuances of body physiology, neuro-disorders (barring brain tumors) provide no space for cell-damaging photothermal effect of NIR for their treatment. Cell-damaging effect, in general, is caused upon longer NIR exposure in the presence of magnetic or other nanoparticles [115–119]. As such, care must be taken to minimize or avoid such damages. In this context, transient NIR exposure in conjugation with nanocarriers can be beneficial. In one such experiment our group has shown that coupling of transient near infrared lights with magnetic nanoparticles is dissipation-free and does not affect the brain cell viability, growth behavior, and neuronal plasticity (Figure 4) [19]. Now this can certainly be extended to NIR-responsive controlled drug delivery in brain because magnetic nanoparticles can transmigrate across BBB under the influence of external magnetic force. Other NIR-responsive nanocarriers may also be useful for the brain drug delivery and have been outlined in table 2. Agarwal et al. showed NIR-triggered release of doxorubicin in mouse model of glioblastoma tumors where nanocarriers included thermosensitive liposomes and gold nanorods [25]. Cheon et al. synthesized functional bovine serum albumin coated GO nano-sheets which could release loaded doxorubicin upon NIR treatment with a purpose to accelerated killing of glioblastoma cell during photothermal treatment [120]. Similarly, Wang et al. synthesized mesoporous silica-coated graphene nanosheet for chemo-photothermal therapy of glioma in response to NIR exposure [121]. In a rare example or neuro-disorders other than brain tumors, GO nanocarriers in conjugation with NIR were shown to disrupt Alzheimer’s pathology causing amyloid-β plaque due to photothermal effect [122] and this approach may also be useful for drug delivery by conjugating nanocarriers with drugs. Other brain-specific NIR-nanophototherapy approaches [118,119,123] may also be shaped into NIR responsive drug delivery carriers. But again, for neuro-disorders other than brain tumors, modulations of NIR exposure time will be required for drug delivery from these carriers, so that non-specific cell death can be avoided. Functionalization of nanocarriers with those materials that can respond during transient NIR exposure will be more accommodating for this purpose.

Figure 4.

Effect of transient coupling of near infrared photonic with magnetic nanoparticle on SKNMC neuroepithelioma cells: Transient NIR exposure in conjugation with nanocarriers may avoid cell-damaging photothermal effect as suggested by Sagar et al.[19]. Confocal microscopy images presented here shows SKNMC neuroepithelioma cells exposed to 808 nm NIR for 2 minutes in the absence (C) or presence (D) of magnetic nanoparticles in compare to control (A & B). Healthy dendrite and spine morphology of SKNMC cells after 72 hours of NIR treatment suggest transient NIR phototargeting do not alter the neuronal synaptic plasticity. Thus, transient NIR coupling with magnetic nanocarriers possesses potential towards safe use for brain biomedical applications [19].

Table 2.

Potential NIR-responsive nanocarriers for brain drug delivery purposes:

| NIR-nanosystems and their components | Disease | Drugs | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO nano-sheets and albumin coating | Glioblastoma | Doxorubicin | Dose-dependent cellular uptake without any cytotoxic effect | Cheon et al. [120] |

| GO nano-sheets and mesoporous silica coating | Glioma | Heptamethine carbocyanine dyes | Prolonged survival of animals | Wang et al. [121] |

| GO nanocarriers with thioflavin-S modifications | Alzheimer | _ | Disruption of amyloid-β plaque | Li et al. [122] |

| Porphyrin immobilized nano-graphene oxide (PNG) | Brain cancer | _ | Tumor elimination | Su et al. [117] |

| PEGylated Gold nanorods and liposomes | Glioblastoma | Doxorubicin | Increase in tumor-site apoptosis | Agarwal et al. [25] |

| Gold-nanoshell-loaded macrophages | Brain tumors | _ | Suppress tumor growth | Christie et al. [118] |

| Poly lactide-co-glycolide (PLGA) | Glioma | Indocyanine green (ICG) and docetaxel (DTX) | Prolonged the life span of brain orthotopic U87MG glioma xenograft-bearing mice | Hao et al. [119] |

| Dye mediated delivery (no nanocarriers were used) | Brain tumors and brain metastases | Heptamethine carbocyanine dyes and Gemcitabine | Restricted growth of both intracranial glioma xenografts and prostate tumor brain metastases and prolonged survival in mice | Wu et al. [123] |

| Transient coupling of NIR with Magnetic Nanoparticles | – | – | No harmful effect on neuronal cells. | Sagar et al. [19] |

5. Biological perspectives of NIR-Nanosystems

While nanoparticles within the permissible dose limit possess non-significant safety concerns, the biological perspectives of NIR exposure must be delineated before “NIR-nanoparticles” coupling for medical purposes. Intrinsically, the human body has evolved multiple layers of protective mechanisms against NIR exposure. Limited NIR exposure may have beneficial applications such as collagen and elastin stimulation, skin rejuvenation, long-lasting vasodilation and, in turn, increased blood circulation, activation of mitochondrial metabolism, prevention of UV-induced toxicity, stem-cell stimulation based regenerative medicine, skin, bone, and nerve angiogenesis, reduction of oxidant-mediated damage of cellular proteins, etc. [124,125]. In contrast, continuous and long-term NIR exposure exerts deleterious effects and this aspect is in frequent use for killing cancerous cells using photodynamic therapy. The kind of NIR exposure required in this therapy also have negative effect on healthy cells or tissues [19,124,125]. Factors that contribute to the NIR-mediated photodisruptive destruction of tumors are their increased sensitivity to NIR which leads to apoptosis. Disassembly of nuclear lamina in cancerous condition exposes cellular DNAs for NIR mediated damage and subsequently apoptosis is induced (intact nuclear lamina in healthy cells absorbs NIR and, in turn, protects DNA from NIR mediated damage) [124]. Nonetheless, different NIR wavelength range must be examined for their case-specific effectiveness and lesser harmful effects. For example, NIR absorption in melanin for wavelength beyond 1100 nm is negligible in compare to 904 nm and therefore different population with high or low body melanin may have different NIR-wavelength recommendations. Undesirable conditions and parameters during specific NIR exposure may induce skin ptosis, photoaging, superficial muscle thinning, photocarcinogenesis, and clouding of cornea and cataract. NIR above 1850 nm can result in heating, painful sensations, and burns [126]. Although probable occurrence of harmful effects during NIR exposure is much lesser than UV-visible lights, cautions recommended by the International Commission on Nonionizing Radiation Protection can prevent any possible injuries in entirety [127].

Assessment of NIR’s impact on molecular integrity of drug is equally essential to determine the physiological and biological effectiveness of NIR biophotonics based nanodrug systems. All aforementioned studies in section 3 & 4 suggest that end-point phenotypical outcomes during treatment of a representative disease have been the major indicating factor of altered or unaltered integrity of drug(s) associated with NIR-nanocarriers. Nonetheless, NIR exposure may induce modifications in the molecular structure depending on composition and molecular bonds. NIR exhibits wave-particle dualism which has been shown to resonate with and absorbed by hydrogen bond containing groups (O-H, C-H, and N-H) and α-helices as well [124]. These groups and helices are abundant in proteins and nucleic acids and therefore, NIR induced resonance, based on their power intensity, possess thereat to the molecular integrity of peptide drugs, siRNA, miRNAs, nucleic acid analogs or other organic drug molecules. Thus, drug integrity assessment before and after NIR exposure must be verified and brought into common practice by technique such as mass spectrophotometry before their real-time application(s) in NIR-based nanodrug delivery systems.

6. Expert opinion

Nanotechnology mediated drug delivery approaches are at crucial juncture because most new strategies are based on only slight changes in similar conventional concepts or materials resulting in absence of clinically useful formulations. Thus, it is imperative to look for ideas outside the current box of nanotechnology. In this review we have summarized different drug release mechanisms of NIR-responsive nanodrug carriers and their applications. The NIR based optical resonance has three purposes in the field of biomedicine: localized heating, localized fluorescence imaging, and localized release of drugs or other chemical substances from the carrier. Various NIR-responsive “smart” nanoagents have been experimented to show their application in targeted drug delivery and these studies have been basis of several intellectual property rights (Table 3). But again these studies, in large, are limited to laboratory based pre-clinical experiments in targeting tumors. By implementing novel advances in the approach we may be able to regularize the sporadic use of current NIR-nanobiophotonics (especially “first window” i.e. 700–1000 nm NIR) for diseases other than cancer. Advances in drug delivery towards clinical trials are results of evolutionary process where numerous trials (and errors) are required to achieve physiological viability of drug carriers. As such, existing challenges of NIR-nanobiophotonics based drug delivery must be addressed to achieve their feasibility for clinical studies. Toxicology remains as the major issue in all fields of nanomedicines including NIR-nanobiophotonics. While most studies suggest use of case-specific safe level of nanocarriers’ concentration (depending on in vitro and in vivo conditions), toxicological inconsistencies for nanocarriers is often noticed. Different measures have been taken to overcome this issue where PEGylation of nanocarriers have been quite successful. This can further be improved by selecting or discovering biocompatible analogous of toxic components of certain nanocarriers. Also, physicochemical factors such as size, shape, surface area, and charge of nanocarriers must be considered to mitigate the toxic effect. Most studies lack thorough evaluation of nanocarriers-cells interaction and its subsequent effect on biological processes such as oxidation, ROS production, ATP production, DNA replication, lysosomal routes, non-immunogenicity, and mitochondrial metabolism. Studying nanocarriers-cells interactions become more important due to cell/tissue specific complexity in surrounding microenvironment where presence of special receptors or enzymes play vital role in driving influx and/or efflux of nanocarriers. The protein corona effect i.e. accumulation of surrounding biomolecules on nanocarriers in physiological ambience is another factor that need attention because it prevents stimuli-responsive drug release from nanocarriers in addition to causing immunotoxicity to some cells. Emphasis must also be given on to examine nanocarriers’ hepatic and renal clearance processes together with their excretion and degradation issues. For NIR coupling to nanoparticles for drug release, a standardization of NIR dose must be conducted such that deleterious thermal effect of irradiation can be precisely limited to the diseased cells, without harming the healthy one. This may be resolved in entirety by discovering biocompatible material(s) that can show efficient NIR absorption and photo-responsiveness even during transient NIR exposure. Thus, dissipation free optico-electronic modulations on material’s exterior can be achieved even upon transient NIR exposure which can be sufficient to disturb the ionic bonds between drugs and carriers and subsequently drug release can be achieved. For the “no-effect” exhibition of cell viability during NIR-nanobiophotonics experiments, an approach to minimize light absorption by cellular cytochromes can be beneficial because this may prevent temperature elevation. Also, moving towards second (1100–1350 nm) and third (1600–1870 nm) NIR spectral window may be more beneficial in solving practical problems of NIR-nanobiophotonics based drug delivery. Additionally, NIR based fluorescent properties can be incorporated in nanocarriers to achieve visually guided drug delivery to precise locations. The focus of next-generation medicine is shifting from conventional drugs to personalized or precision medicine and therefore improvement in NIR nanobiophotonics is required for successful delivery of those therapeutic agents which can exert the desired temporal/permanent genetic changes such as siRNA, miRNA, CRISPR, etc. Overall, at present NIR-nanobiophotonics based drug delivery possess excellent prospect where their clinical success will depend on pace of scientific efforts in resolving the aforementioned challenges with assimilation of new technologies.

Table 3. List of patents for NIR biophotonics based nanodrug release systems.

A search for “Near Infrared + Drug Delivery” from the website of the world intellectual property organization (https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/search.jsf) were scrutinized and following patents relating to NIR biophotonics based nanodrug release systems were found:

| Patent No. | Title |

|---|---|

| US20110318415 | Hollow gold nanospheres (HAuNSs) and HAuNSs-loaded microspheres useful in drug delivery |

| US20100285994 | Gold nanoparticle composition, DNA chip, near infrared absorbent, drug carrier for drug delivery system (dds), coloring agent, biosensor, cosmetic, composition for in vivo diagnosis and composition for therapeutic use |

| US20140369935 | Liposome composite body |

| US20020169235 | Temperature-sensitive polymer/nanoshell composites for photothermally modulated drug delivery |

| US09233147 | Nano-vector prodrug delivery system |

| US20100228237 | gold nanocages containing magnetic nanoparticles |

| US20120283695 | Transdermal drug delivery patch and method of controlling drug release of the same by near-IR |

| CN104056269 | Drug-delivering system for glioma combined therapy |

| CN104436210 | Malignant-tumour-resistant graphene oxide nano-drug delivery system and preparation method thereof |

| CN104771756 | Preparation method and application of rare earth up-conversion drug-delivery nano-carrier |

| US20100003326 | Drug delivery device comprising a pharmaceutically or biologically active component and an infrared absorbing compound |

| CN101954085 | Method for preparing magnetic-targeted thermos-chemotherapy gold shell nano-drug delivery system |

| US20140193331 | Multifunctional infrared-emitting composites |

| US20110230568 | Heating of polymers and other materials using radiation for drug delivery and other applications |

| US20100224823 | Superparamagnetic colloidal nanocrystal structures |

| US20060099146 | NIR-sensitive nanoparticle |

| US20140120167 | Multifunctional chemo- and mechanical therapeutics |

| US20130115295 | Rare earth-doped up-conversion nanoparticles for therapeutic and diagnostic applications |

| US20150258195 | Polymeric nanocarriers with light-triggered release mechanism |

| US20140308208 | Caged compound delivery and related compositions, methods and systems |

| US20110052671 | Near infra-red pulsed laser triggered drug release from hollow nanoshell disrupted vesicles and vesosomes |

| US20100189650 | Near-infrared responsive carbon nanostructures |

Article highlights box.

Optical characteristics, in general, are strongly dictated by particle size and therefore nanomaterials have improved optical properties than their macroscopic structures.

NIR-nanobiophotonics provide unique advantage in utilizing non-ionizing radiation for noninvasive tissue penetration and the NIR based optical resonance has three major purposes in the field of biomedicine: localized heating, localized fluorescence imaging, and localized release of drugs or other chemical substances from the carrier.

Dependent upon the composition of nanocarriers, NIR-responsive drug delivery can be achieved by three strategies: a) Self-disruption of nanocarriers in response to NIR exposure, b) Disruption of NIR-labile caging bonds, and c) Unlocking of NIR responsive “gate-keepers” caging.

Transient NIR exposure strategy in conjugation with nanocarriers may be useful for brain specific targeting because cell-damaging photothermal effect is reduced to zero in case of transient NIR exposure.

Biological perspectives of NIR exposure in different population groups must be delineated before “NIR-nanoparticles” coupling for real-time medical purposes.

Advances in drug delivery towards clinical trials are results of evolutionary process where numerous trials (and errors) are required to achieve physiological viability of drug carriers. As such, existing challenges of NIR-nanobiophotonics based drug delivery must be addressed to achieve their feasibility for clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants R01DA040537, R01DA037838, and R01DA034547 from the National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1•.Yun YH, Lee BK, Park K. Controlled Drug Delivery: Historical perspective for the next generation. J Control Release [Internet] 2015;219:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.10.005. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.10.005). This review includes nice critics of different drug delivery technologies in historical perspectives and their prospects for achieving physiological relevance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu Y, Kim S, Park K. In vitro – in vivo correlation : Perspectives on model development. Int J Pharm [Internet] 2011;418:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.01.010. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3••.Sagar V, Pilakka-Kanthikeel S, Pottathil R, et al. Towards nanomedicines for neuroAIDS. Rev Med Virol. 2014;24:103–124. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1778. This is an extensive review of various nanocarriers for their use in neurological disorders with emphasis on neuroAIDS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Mura S, Nicolas J, Couvreur P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery. Nat Mater [Internet] 2013;12:991–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat3776. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmat3776.) Nice descriptions of all stimuli-responsive nanosystems and how these may be useful for clinical applications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karimi M, Ghasemi A, Sahandi Zangabad P, et al. Smart micro/nanoparticles in stimulus-responsive drug/gene delivery systems [Internet] Chem Soc Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1039/c5cs00798d. Available from: http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=C5CS00798D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Song J, Qu J, Swihart MT, et al. Near-IR responsive nanostructures for nanobiophotonics: Emerging impacts on nanomedicine. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology Biol Med [Internet] 2016;12:771–788. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.11.009. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bansal A, Zhang Y. Photocontrolled nanoparticle delivery systems for biomedical applications. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:3052–3060. doi: 10.1021/ar500217w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim H, Chung K, Lee S, et al. Near-infrared light-responsive nanomaterials for cancer theranostics. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomedicine Nanobiotechnology. 2016;8:23–45. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bao Z, Liu X, Liu Y, et al. Near-infrared light-responsive inorganic nanomaterials for photothermal therapy. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2015;11:349–364. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu B, Li C, Cheng Z, et al. Functional nanomaterials for near-infrared-triggered cancer therapy. Biomater Sci [Internet] 2016 doi: 10.1039/c6bm00076b. Available from: http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=C6BM00076B. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Chacko AM, Hood ED, Zern BJ, et al. Targeted nanocarriers for imaging and therapy of vascular inflammation. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2011:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva AKA, Letourneur D, Chauvierre C. Polysaccharide nanosystems for future progress in cardiovascular pathologies. Theranostics. 2014:579–591. doi: 10.7150/thno.7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moghimi SM, Szebeni J. Stealth liposomes and long circulating nanoparticles: Critical issues in pharmacokinetics, opsonization and protein-binding properties. Prog Lipid Res. 2003:463–478. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunaseelan S, Gunaseelan K, Deshmukh M, et al. Surface modifications of nanocarriers for effective intracellular delivery of anti-HIV drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010:518–531. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chellat F, Merhi Y, Moreau A, et al. Therapeutic potential of nanoparticulate systems for macrophage targeting. Biomaterials. 2005;26:7260–7275. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nair M, Jayant RD, Kaushik A, et al. Getting into the brain: Potential of nanotechnology in the management of NeuroAIDS. Adv Drug Deliv Rev [Internet] 2016;103:202–217. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.02.008. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0169409X1630059X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikehara Y, Niwa T, Biao L, et al. A carbohydrate recognition-based drug delivery and controlled release system using intraperitoneal macrophages as a cellular vehicle. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8740–8748. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim BYS, Rutka JT, Chan WCW. Nanomedicine. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2010;363:2434–2443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0912273. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMra0912273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19••.Sagar V, Atluri VSR, Tomitaka A, et al. Coupling of transient near infrared photonic with magnetic nanoparticle for potential dissipation-free biomedical application in brain. Sci Rep [Internet] 2016;6:29792. doi: 10.1038/srep29792. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/srep29792.) This research article shows an important observation that transient coupling of NIR with nanoparticles is dissipation-free and have no adverse effect on the brain cell viability, growth behavior, and neuronal plasticity. Thus, approach may be very useful in brain drug delivery. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michalet X, Pinaud FF, Bentolila La, et al. Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. Science [Internet] 2005;307:538–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1201471&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sönnichsen C, Franzl T, Wilk T, et al. Drastic reduction of plasmon damping in gold nanorods. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;88:77402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.077402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Kelly KL, Coronado E, Zhao LL, et al. The Optical Properties of Metal Nanoparticles: The Influence of Size, Shape, and Dielectric Environment. J Phys Chem B [Internet] 2003;107:668–677. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jp026731y\nhttp://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jp026731y. This article explains how optical properties of metal nanoparticles are influenced by shapes, sizes and dielectric environments. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen S, Tang H, Zhang X, et al. Targeting mesoporous silica-encapsulated gold nanorods for chemo-photothermal therapy with near-infrared radiation. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3150–3158. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Wang L, Wang J, et al. Mesoporous Silica Coated Gold Nanorods as a Light Mediated Multifunctional Theranostic Platform for Cancer Treatment. Adv Mater. 2012;24:1418–1423. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agarwal A, MacKey MA, El-Sayed MA, et al. Remote triggered release of doxorubicin in tumors by synergistic application of thermosensitive liposomes and gold nanorods. ACS Nano. 2011;5:4919–4926. doi: 10.1021/nn201010q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu G, Mikhailovsky A, Khant HA, et al. Remotely triggered liposomal release by near-infrared light absorption via hollow gold nanoshells. J Am Chem Soc [Internet] 2008;130:8175–8177. doi: 10.1021/ja802656d. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2593911/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niidome T. 近赤外光でコントロールする薬物デリバリーシステム 新留 琢郎 (Drug Delivery System Controlled by Near Infrared Light) The Pharmaceutical Society of Japan. 2013;133:11–14. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.12-00239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma Y, Liang X, Tong S, et al. Gold nanoshell nanomicelles for potential magnetic resonance imaging, light-triggered drug release, and photothermal therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23:815–822. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strong LE, West JL. Hydrogel-Coated Near Infrared Absorbing Nanoshells as Light-Responsive Drug Delivery Vehicles. ACS Biomater Sci Eng [Internet] 2015 doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00111. 150713080020006. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Ko H, Son S, Bae S, et al. Near-infrared light-triggered thermochemotherapy of cancer using a polymer–gold nanorod conjugate. Nanotechnology. 2016:175102. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/27/17/175102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Camposeo A, Persano L, Manco R, et al. Metal-Enhanced Near-Infrared Fluorescence by Micropatterned Gold Nanocages. ACS Nano. 2015;9:10047–10054. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren L, Chow GM, Systems C. Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Mol Eng [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fong WK, Hanley TL, Thierry B, et al. External manipulation of nanostructure in photoresponsive lipid depot matrix to control and predict drug release in vivo. J Control Release. 2016;228:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34•.Timko BP, Arruebo M, Shankarappa SA, et al. Near-infrared-actuated devices for remotely controlled drug delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA [Internet] 2014;111:1349–1354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322651111. Available from: http://www.pnas.org/content/111/4/1349. This research article shows development of implantable reservoirs that release drug in response to NIR irradiation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li N, Yu Z, Pan W, et al. A near-infrared light-triggered nanocarrier with reversible DNA valves for intracellular controlled release. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23:2255–2262. [Google Scholar]

- 36•.Yavuz MS, Cheng Y, Chen J, et al. Gold nanocages covered by smart polymers for controlled release with near-infrared light. Nat Mater [Internet] 2009;8:935–939. doi: 10.1038/nmat2564. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmat2564. This research is an excellent example of controlled drug release by unlocking of NIR responsive “gate-keepers” caging. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park J, Park J, Ju EJ, et al. Multifunctional hollow gold nanoparticles designed for triple combination therapy and CT imaging. J Control Release. 2015;207:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pissuwan D, Nose K, Kurihara R, et al. A Solid-in-Oil Dispersion of Gold Nanorods Can Enhance Transdermal Protein Delivery and Skin Vaccination. 2011:215–220. doi: 10.1002/smll.201001394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nose K, Pissuwan D, Goto M, et al. Gold nanorods in an oil-base formulation for transdermal treatment of type 1 diabetes in mice. Nanoscale [Internet] 2012;4:3776–3780. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30651d. Available from: <Go\nto\nISI>://WOS:000304666700030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamashita S, Fukushima H, Akiyama Y, et al. Controlled-release system of single-stranded DNA triggered by the photothermal effect of gold nanorods and its in vivo application. Bioorganic Med Chem [Internet] 2011;19:2130–2135. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.02.042. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2011.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Y, Liu J, Sun X, et al. Near-infrared light-activated cancer cell targeting and drug delivery with aptamer-modified nanostructures. Nano Res. 2016;9:139–148. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen CC, Lin YP, Wang CW, et al. DNA-gold nanorod conjugates for remote control of localized gene expression by near infrared irradiation. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3709–3715. doi: 10.1021/ja0570180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]