Abstract

The current report presents data on lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation and nonfatal attempts as reported by the large representative sample of U.S. Army soldiers who participated in the Consolidated All Army Survey (AAS) of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS; n=29,982). We also examine associations of key Army career characteristics with these outcomes. Prevalence estimates for lifetime suicidal ideation are 12.7% among men and 20.1% among women, and for lifetime suicide attempts are 2.5% and 5.1%, respectively. Retrospective age-of-onset reports suggest that 53.4%–70.0% of these outcomes had pre-enlistment onsets. Results revealed that, for both men and women, being in the Regular Army, compared with being in the National Guard or Army Reserve, and being in an enlisted-rank, compared with being an officer, is associated with increased risk of suicidal behaviors and that this elevated risk is present both before and after joining the Army.

The suicide rate in the US Army has historically been below the civilian rate (Bachynski et al., 2012), but increased dramatically in the years following the start of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (Kuehn, 2009; Nock et al., 2013). As a result of this increase, among several suicide prevention efforts, the Army initiated Army STARRS (http://starrs-ls.org), a large-scale epidemiological study, to better understand the correlates and causes of suicide among soldiers (Ursano et al., 2014).

One goal of Army STARRS is to identify factors associated with heightened suicide risk and determine when this risk first occurred to generate hypotheses about why soldiers are at-risk and the optimal time to intervene with help. Prior Army STARRS reports have focused on describing the prevalence of non-lethal suicidal behaviors to examine a wider scope of risk than suicide death and determining the extent to which soldiers enter the Army already at heightened risk for suicidal behaviors versus increased risk that occurs only following Army enlistment. Understanding pre- versus post-enlistment risk is important because it can help address whether soldiers enter the Army with pre-existing suicidal behaviors or onset of these behaviors only occurs following Army-related experiences (e.g. combat). Furthermore, measures the Army could take to reduce suicidal risk would depend greatly on when certain factors increase risk. For example, substantial pre-enlistment risk could lead to changes in recruitment screening procedures whereas substantial post-enlistment risk might require efforts to psychologically prepare soldiers for experiences that elevate risk.

Army STARRS has started to provide a first glimpse into pre- versus post-enlistment suicidal risk across several different classes of factors, such as demographic differences and mental disorders. In a prior Army STARRS report, Nock and colleagues (2014) used data from early replicates of the STARRS All Army Survey (AAS), a large, representative survey of active duty Regular Army soldiers, to estimate prevalence and basic correlates of self-reported non-lethal suicidal behaviors. Lifetime prevalence estimates of suicide ideation, plans, and attempts were 13.9%, 5.3% and 2.4%, respectively. Retrospective age-of-onset reports estimated that half of the soldiers with lifetime ideation and plans began thinking and planning suicides prior to enlistment, that 47.0% of the soldiers who ever made nonfatal suicide attempts made their first attempts prior to age at enlistment, and that 31.3% of suicide attempts after enlistment were associated with pre-enlistment mental disorders (Nock et al., 2014). These results implied that increased risk of suicidal behaviors in the Army was due partly to pre-existing vulnerabilities among soldiers and not exclusively to Army experiences; but they were limited by the fact that the sample on which the results were based was small (n=5,428) and excluded both soldiers that were deployed and soldiers in the Army National Guard and Army Reserve (G/R). The current report presents data on the full Consolidated AAS sample (n=29,982), which includes soldiers who were deployed to Afghanistan at the time of the survey as well as G/R soldiers.

In addition to other factors, Nock et al. (2014) examined whether suicide risk varied across career characteristics, such as rank. Examining the association between career characteristics and suicide risk is important because identifying careers with higher suicide risk would help the Army target groups of soldiers requiring greater monitoring and additional psychiatric services. In addition, although it is assumed that some careers are at increased risk of suicidal behaviors because of Army experiences (e.g. trauma), some careers may exhibit higher suicide risk due to soldiers entering into these careers with suicidal behaviors prior to enlistment. However, no studies have examined this question.

The first aim of this report is to provide updated prevalence estimates for pre- and post-enlistment suicidal behaviors in the Army based on a larger and more broadly representative sample in the full Consolidated AAS than in the earlier Nock et al. report. The second aim is to expand the Nock et al. (2014) analysis to examine associations of three critical Army career characteristics – rank, occupation, and component (i.e., Regular Army versus Army National Guard/Army Reserve) -- with self-reported suicidal behaviors separately for the subset of these behaviors that began prior to enlistment and those that began only after enlistment. This specification goes beyond previous studies, a number of which have documented associations of these career characteristics with suicidality (Kessler et al., 2015; Nock et al., 2014; Ursano, Heeringa, et al., 2015; Ursano, Kessler, Stein, et al., 2015), by investigating the possibility that these associations are due to selection processes rather than to experiences associated with the career characteristics (e.g., higher exposure to traumatic experiences by soldiers in combat arms occupations than other occupations) (Nock et al., 2014). We did this by treating these career characteristics as predictors of first onset of the outcomes both before and after age-at-enlistment. Based on the early ages-of-onset of these outcomes found by Nock et al. (2014), we would expect that soldiers who subsequently had career characteristics associated with increased risk of suicidality in the Nock et al. (2014) report might have had high risk of these same outcomes before enlistment, whereas we would expect those associations to emerge only after enlistment if military experiences accounted for the associations. We are unaware of any previous attempt to examine these important specifications.

Prior studies have found that junior rank enlisted soldiers have higher risk of suicide death and suicidal behaviors than soldiers of higher rank (Gilman et al., 2014; Nock et al., 2014; Reger et al., 2015; Ursano, Kessler, Heeringa, et al., 2015) and that soldiers in combat-related occupations (i.e. combat arms; (Gadermann et al., 2014) have higher rates of suicide death than those in other occupations (Helmkamp, 1996; Kessler et al., 2015; Trofimovich, Reger, Luxton, & Oetjen-Gerdes, 2013), but it is not known whether these associations apply as well to the range of suicidal behaviors considered in this report. In addition to rank and occupation, differences in suicidal behavior may vary among Regular Army and G/R components. Suicide rates over the past decade have increased in both the Regular Army and G/R (Black, Gallaway, Bell, & Ritchie, 2011; Griffith, 2012), but few studies have examined whether suicidal behaviors differ between components. Ursano, Heeringa and colleagues (2015) reported a higher lifetime rate of suicidal ideation among activated G/R soldiers than soldiers in the Regular Army during the first week of Basic Combat Training (BCT) but we are unaware of any studies on suicidal behaviors that have directly compared active soldiers serving in the Regular Army versus G/R.

The large sample size included in this study provides a unique opportunity to test associations between career variables and suicidal ideation, plans and attempts and whether onset of these behaviors occurred before or after joining the Army. Importantly, given that the percentage of women varies greatly across career positions and women consistently show higher rates of non-lethal suicidal behaviors (Nock et al., 2014; Ursano, Heeringa, et al., 2015; Ursano, Kessler, Stein, et al, 2015), associations between particular careers and suicidal behaviors could be inflated by the presence of a larger proportion of women. To control for this potential confound, we examined models that included interactions with gender and focused on models stratified by gender. Examining gender and career characteristics is also important because new Army policies, such as lifting the ban on women joining ground combat units in 2013, allow women to have career roles not historically available to them (Servick, 2015) with unknown consequences for suicide risk.

METHOD

Sample

Data came from self-report questionnaires (SAQs) collected in a series of three Army STARRS surveys and merged into a dataset we refer to as the Consolidated All-Army Survey to create a portrait of all active duty soldiers exclusive of those in Basic Combat Training. The first of the three surveys was the All-Army Survey (AAS), a de-identified cross-sectional survey of active duty soldiers exclusive of those in Basic Combat Training or deployed to a combat theatre based on quarterly replicates in 2011–2012 and additional G/R units in 2013 of stratified (by Army Command-location) probability samples of units or sub-units selected with probabilities proportional to authorized unit strength excluding units of fewer than 30 soldiers (less than 2% of Army personnel). All personnel in the selected units were ordered to attend an informed consent presentation explaining study purposes, confidentiality, and voluntary participation before requesting written informed consent for a group SAQ, to link their administrative records to questionnaire responses, and to participate in future data collections. Identifying information (e.g., name, SSN) was collected from consenting respondents and kept in a separate secure file.

A total of 17,462 AAS respondents completed the SAQ and provided consent for administrative data linkage. Although all unit members were ordered to report to informed consent sessions, 20.2% were absent due to conflicting duty assignments. The vast majority of attendees (95.0%) consented to the survey, 97.3% of consenters completed the survey, and 63.1% of completers provided record linkage. Most incomplete surveys were due to logistical complications (e.g., units either arriving late or having to leave the 90-minute sessions early), although some respondents needed more than the allotted time to complete the survey. The survey completion-successful-linkage cooperation rate was 58.3% (.95×.973×.631) and the response rate 46.5% ([1-.202]x.583) based on the American Association of Public Opinion Research COOP1 and RR1 calculation methods (American Association for Public Opinion Research, 2009).

As the AAS did not include soldiers currently deployed to a combat zone, a special AAS supplemental sample was selected of soldiers deployed in Afghanistan. Unlike the main AAS, though, constraints on our ability to administer surveys in Afghanistan led us to implement the data collection in Kuwait with soldiers who were waiting to be processed for transit to and from their mid-deployment leave. In all other respects, though, the recruitment, consent, and data collection procedures were identical to those in the main AAS. A total of 3,987 respondents completed the SAQ and provided consent for administrative data linkage. A majority of soldiers (80.9%) consented to the survey, 86.5% of consenters completed the survey, and 55.6% of completers provided record linkage, for a survey completion-successful-linkage cooperation rate of 38.9% (.809x.865x.556). The response rate could not be calculated because data were not collected on the denominator population of soldiers invited to the sessions.

Another Army STARRS survey was a prospective pre-post deployment survey (PPDS) of soldiers in three Brigade Combat Teams initially assessed shortly before deploying to Afghanistan and then again three times after returning from deployment. We merged the baseline PPDS with the AAS and Kuwait supplement to the AAS in order to enrich the consolidated sample for soon-to-deploy units that were under-represented because of logistical complications in the main AAS. The recruitment, consent, and data collection procedures were identical to those in the main AAS. 8,558 respondents completing the baseline PPDS SAQ and providing consent for administrative data linkage. The vast majority of soldiers recruited into the PPDS attended the consent session (96.7%), with 98.7% of the latter consenting to the survey, 99.2% of consenters completed the survey, 90.9% of completers providing record linkage, for a survey completion-successful-linkage cooperation rate of 89.0% (.987x.992x.909) and a response rate of 86.1% (.967x.89).

The recruitment, consent, and data protection procedures in the above surveys were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences for the Henry M. Jackson Foundation (the primary grantee), the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan (the organization collecting the data), and all other collaborating organizations. SAQ responses of participants in the surveys who agreed to administrative data linkage were doubly-weighted before combining to adjust for discrepancies between the sample and population. The first weight (W1) adjusted for differences in survey responses between the respondents who agreed to record linkage and those who did not. The second weight (W2) adjusted for differences in multivariate administrative record profiles of weighted (W1) survey completers with record linkage and the target population. The latter weight adjusted the sample to be representative of all active duty soldiers during the years 2011–2012 on the cross-classification of socio-demographics (age, sex, race-ethnicity, education, marital status), command (e.g., Forces Command, Training and Doctrine Command, Reserve Command [Army Reserve, Army National Guard], Component Commands), occupation (Combat Arms, Combat Support, Combat Service Support), rank (E1–E4, E5–E9, W1–W4, O1–O10), and deployment status-history (never-deployed, currently-deployed [the Kuwait supplemental sample], previously deployed). The Doubly-weighted (W1xW2) data were combined to create the Consolidated All-Army Survey. A more detailed description of AAS weighting is presented elsewhere (Kessler, Heeringa, et al., 2013). Finally, participants (n = 25) with unknown survey dates were omitted from the final analytic sample.

Measures

Suicidal behaviors

Suicidal behaviors were assessed using a modified version of the Columbia Suicidal Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; (Posner et al., 2011) that assessed lifetime occurrence and age-of-onset (AOO) of suicide ideation (“Did you ever in your life have thoughts of killing yourself” or “Did you ever wish you were dead or would go to sleep and never wake up?”) and, among respondents who reported lifetime ideation, suicide plans (“Did you ever have any intention to act [on these thoughts/on that wish]?” and, if so, “Did you ever think about how you might kill yourself [e.g., taking pills, shooting yourself] or work out a plan of how to kill yourself?”) and attempts (“Did you ever make a suicide attempt [i.e., purposefully hurt yourself with at least some intention to die]?”).

Socio-demographic and Army career variables

The socio-demographic variables we focus on here are respondent age and sex. The Army career variables considered are age-at-enlistment, component (Regular Army versus Reserve Component [i.e., activated G/R]), Military Occupational Specialty (MOS), and rank (junior enlisted E1–E4, senior enlisted E5–E9, and officers [combining Warrant officers and Commissioned officers]). Consistent with previous work on occupational differences in soldier health (Gubata, Piccirillo, Packnett, & Cowan, 2013; Lindstrom et al., 2006; Niebuhr et al., 2011), we distinguished three broad classes of occupations: combat arms occupations, which are involved directly in ground combat; combat support occupations, which provide operational assistance to combat arms; and all other occupations, which are referred to collectively as combat service support occupations (Kirin & Winkler, 1992; Layne, Naftel, Thie, & Kawata, 2001). A more detailed discussion of MOS coding in STARRS is presented elsewhere (Kessler et al., 2015).

Analysis Methods

Retrospective age-of-onset reports were analyzed using the two-part actuarial method to estimate survival curves, a method differing from the Kaplan-Meier (Kaplan & Meier, 1958) method in using a more accurate way of estimating onsets within a given year (Halli & Rao, 1992). Both absolute morbid risk (cumulative lifetime risk of ever having suicide ideation, developing a plan, or making an attempt) and relative morbid risk (the proportion of total morbid risk at each age) are reported for each outcome. Discrete-time survival analysis, with person-year the unit of analysis and a logistic link function (Efron, 1988) was used to examine associations of predictors with onset of suicidal behavior. Pre-/post-enlistment was a time-varying predictor while component, rank and occupation were considered only at the time of survey administration. Unlike conventional survival analysis, where predictors are assessed as of a time prior to the time of the outcome assessment, we consider post-enlistment career variables as “predictors” of pre-enlistment suicidality as a way of investigating the possible existence of predisposing factors that predict both pre-enlistment suicidality and post-enlistment selection into components and occupations. Survival coefficients were exponentiated to create odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (Halli & Rao, 1992; Kaplan & Meier, 1958). As the Consolidated AAS data are both clustered and weighted, the design-based Taylor series linearization method was used to produce standard errors (Wolter, 1985). Multivariate significance was examined using design-based Wald F tests.

RESULTS

Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset of suicidal behaviors

Lifetime prevalence estimates of suicide ideation are 12.7% among men and 20.1% among women in the total AAS. (Table 1) Lifetime prevalence estimates of suicide attempts are 2.5% among men and 5.1% among women. Female gender is associated with significantly greater odds of suicide ideation (OR=1.7 [95% CI: 1.5–2.0]) and attempt (OR=2.2 [1.7–3.0]). Women also have slightly higher rates (but not significantly so) of the three transition probabilities we examined between ideation and attempts – the probability that ideators go on to develop a suicide plan (41.8% among men versus 46.0% among women; OR=1.0 [0.8–1.3]); the probability that ideators with a plan go on to make an attempt (33.9% among men versus 38.3% among women; OR=1.3 [0.9–1.9]), and the probability that ideators without a plan make an attempt (14.8% among women versus 9.2% among men; OR=1.6 [1.0–2.7]).

Table 1.

Lifetime suicidality by selected army characteristics, stratified by sex, weighted analysis (n=29,982)

| Total sample | Ideators | Ideators with plan | Ideators without plan | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lifetime ideation | Lifetime attempt | Lifetime plan | Lifetime attempt | Lifetime attempt | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| % | SE | n numerator |

n denominator |

% | SE | n numerator |

n denominator |

% | SE | n numerator |

n denominator |

% | SE | n numerator |

n denominator |

% | SE | n numerator |

n denominator |

|

| Men | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Component: Regular army | 13.2 | 0.4 | (3,135) | (24,788) | 2.6 | 0.2 | (598) | (24,788) | 41.1 | 1.7 | (1,083) | (3,135) | 35.5 | 2.0 | (392) | (1,057) | 9.0 | 1.0 | (206) | (2,078) |

| Component: Guard-reserve | 8.4 | 0.9 | (209) | (2,139) | 1.2 | 0.2 | (37) | (2,139) | 52.3 | 4.5 | (111) | (209) | 16.1 | 3.0 | (24) | (111) | 11.6 | 3.4 | (13) | (98) |

| F(1,210), p-value | 24.8* | <.001 | 26.8* | <.001 | 5.0* | 0.026 | 15.4* | <.001 | 0.6 | 0.46 | ||||||||||

| MOS: Combat arms | 12.4 | 0.4 | (1,622) | (13,371) | 2.5 | 0.2 | (311) | (13,371) | 38.1 | 2.4 | (533) | (1,622) | 40.1 | 2.9 | (201) | (522) | 8.8 | 1.1 | (110) | (1,100) |

| MOS: Combat support | 12.7 | 0.8 | (746) | (5,877) | 2.4 | 0.4 | (145) | (5,877) | 46.5 | 3.1 | (291) | (746) | 29.0 | 5.0 | (93) | (282) | 10.4 | 1.8 | (52) | (464) |

| MOS: Combat service support | 13.3 | 0.7 | (976) | (7,679) | 2.4 | 0.3 | (179) | (7,679) | 43.2 | 2.3 | (370) | (976) | 30.8 | 3.4 | (122) | (364) | 8.9 | 1.9 | (57) | (612) |

| F(2,209), p-value | 0.8 | 0.47 | 0.1 | 0.88 | 2.7 | 0.07 | 3.1* | 0.045 | 0.3 | 0.74 | ||||||||||

| Rank: Junior | 12.7 | 0.4 | (1,706) | (14,370) | 2.9 | 0.3 | (363) | (14,370) | 39.8 | 2.5 | (584) | (1,706) | 39.7 | 3.3 | (220) | (566) | 12.1 | 1.3 | (143) | (1,140) |

| Rank: Senior | 13.2 | 0.6 | (1,260) | (9,497) | 2.5 | 0.2 | (240) | (9,497) | 44.8 | 3.0 | (480) | (1,260) | 34.1 | 2.7 | (175) | (472) | 7.0 | 1.4 | (65) | (788) |

| Rank: Officer | 12.0 | 1.1 | (378) | (3,060) | 1.2 | 0.3 | (32) | (3,060) | 40.6 | 5.1 | (130) | (378) | 17.0 | 4.0 | (21) | (130) | 5.3 | 2.2 | (11) | (248) |

| F(2,209), p-value | 0.5 | 0.62 | 7.8* | <.001 | 0.8 | 0.46 | 9.8* | <.001 | 7.0* | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Total | 12.7 | 0.4 | (3,344) | (26,927) | 2.5 | 0.2 | (635) | (26,927) | 41.8 | 1.6 | (1,194) | (3,344) | 33.9 | 1.9 | (416) | (1,168) | 9.2 | 0.9 | (219) | (2,176) |

| Pre-enlistment suicidality risk | 61.2 | 1.3 | (2,164) | (3,344) | 56.7 | 3.4 | (390) | (635) | 55.7 | 2.0 | (739) | (1,194) | 57.9 | 4.2 | (262) | (416) | 53.5 | 5.2 | (128) | (219) |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Women | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Component: Regular army | 21.1 | 0.9 | (530) | (2,751) | 5.2 | 0.6 | (155) | (2,751) | 44.7 | 3.3 | (233) | (530) | 37.3 | 4.8 | (105) | (227) | 15.1 | 2.5 | (50) | (303) |

| Component: Guard-reserve | 11.4 | 2.3 | (45) | (304) | 4.0 | 1.4 | (15) | (304) | 68.0 | 9.4 | (30) | (45) | 49.3 | 7.9 | (14) | (29) | 7.1 | 6.9 | (1) | (16) |

| F(1,210), p-value | 12.4* | <.001 | 0.7 | 0.42 | 3.5 | 0.06 | 1.1 | 0.29 | 1.1 | 0.30 | ||||||||||

| MOS: Combat arms | 13.5 | 2.3 | (40) | (217) | 4.5 | 1.6 | (14) | (217) | 46.5 | 9.9 | (19) | (40) | 60.1 | 12.1 | (11) | (19) | 10.3 | 6.5 | (3) | (21) |

| MOS: Combat support | 20.7 | 2.0 | (160) | (765) | 5.8 | 1.1 | (50) | (765) | 44.8 | 6.0 | (73) | (160) | 44.4 | 9.0 | (36) | (72) | 15.6 | 3.9 | (14) | (88) |

| MOS: Combat service support | 20.6 | 1.0 | (375) | (2,073) | 4.9 | 0.6 | (106) | (2,073) | 46.4 | 4.1 | (171) | (375) | 34.9 | 5.3 | (72) | (165) | 14.8 | 3.5 | (34) | (210) |

| F(2,209), p-value | 3.8* | 0.024 | 0.3 | 0.74 | 0.0 | 0.97 | 1.3 | 0.27 | 0.3 | 0.77 | ||||||||||

| Rank: Junior | 17.9 | 1.2 | (299) | (1,723) | 6.2 | 0.9 | (103) | (1,723) | 50.5 | 4.7 | (138) | (299) | 48.8 | 6.4 | (75) | (136) | 21.3 | 4.9 | (28) | (163) |

| Rank: Senior | 21.8 | 2.0 | (183) | (887) | 5.0 | 0.8 | (53) | (887) | 41.7 | 5.3 | (87) | (183) | 35.7 | 6.7 | (34) | (82) | 14.5 | 4.4 | (19) | (101) |

| Rank: Officer | 22.8 | 1.9 | (93) | (445) | 2.5 | 0.7 | (14) | (445) | 44.4 | 6.3 | (38) | (93) | 19.6 | 6.2 | (10) | (38) | 3.9 | 2.1 | (4) | (55) |

| F(2,209), p-value | 2.4 | 0.09 | 5.0* | 0.007 | 0.8 | 0.45 | 4.3* | 0.015 | 6.1* | 0.003 | ||||||||||

| Total | 20.1 | 0.9 | (575) | (3,055) | 5.1 | 0.5 | (170) | (3,055) | 46.1 | 3.2 | (263) | (575) | 38.3 | 4.4 | (119) | (256) | 14.8 | 2.4 | (51) | (319) |

| Pre-enlistment suicidality risk | 70.0 | 2.6 | (400) | (575) | 64.3 | 6.1 | (122) | (170) | 68.6 | 4.1 | (185) | (263) | 65.7 | 7.8 | (89) | (119) | 61.4 | 10.6 | (33) | (51) |

Male lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts is significantly higher among soldiers who at the time of survey were in the Regular Army than the G/R (2.6% versus 1.2%; F(1,210)=26.8, p<.001) and among junior and senior enlisted soldiers than officers (2.9–2.5% versus 1.2%; F(2,209)=7.8, p<.001), but does not differ by MOS at the time of survey (F(2,209)=0.1, p=.88). The significant association with component is due to Regular Army soldiers having significantly higher prevalence than those in the G/R of ideation in the total sample (13.2% versus 8.4%; F(1,210)=24.8, p<.001) and of attempts among planners (35.5% versus 16.1%; F(1,210)=15.4, p<.001) despite having a significantly lower probability of plans among ideators (41.1% versus 52.3%; F(1,210)=5.0, p=.03). The significant association with rank is due to enlisted soldiers having significantly higher prevalence than officers of attempts both among planners (39.7–34.1% versus 17.0%; F(2,209)=9.8, p<.001) and among ideators without a plan (12.1–7.0% versus 5.3%; F(2,209)=7.0, p<.001) despite not differing in prevalence of ideation in the total sample F(2,209)=0.5, p=.62) or plans among ideators F(2,209)=0.8, p=.46). In other words, officers are as likely as enlisted soldiers to think-plan about suicide but significantly less likely to act on those thoughts-plans.

The situation is somewhat different for female soldiers, where prevalence of suicide attempts is significantly higher among junior and senior enlisted soldiers than officers (6.2–5.0% versus 2.5%; F(2,209)=5.0, p=.01), but does not differ by component (F(1,210)=0.7, p=.42), or MOS F(2,209)=0.3, p=.74). As with males, the significant association of rank with suicide attempts among female soldiers is due to enlisted soldiers having significantly higher prevalence than officers of attempts both among planners (48.8–35.7% versus 19.6%; F(2,209)=4.3, p=.02) and among ideators without a plan (21.3–14.5% versus 3.9%; F(2,209)=6.1, p<001) despite not differing in prevalence either of ideation (F(2,209)=2.4, p=.09) or of plans among ideators (F(2,209)=0.8, p=.45).

The last row in both the male and female panels of Table 1 presents a summary statistic about the timing of suicidality: the proportion of all cases where the outcome defined in the column first occurred prior versus subsequent to the soldier’s age of enlistment. The majority of cases of each outcome among both males (53.4–61.2%) and females (61.4–70.0%) first occurred before age of enlistment. The highest proportion for both males and females is for ideation, with 61.2% of the males and 70.0% of the females with lifetime ideation reporting that they first thought about suicide prior to age of enlistment. The lowest proportion for both males and females, in comparison, is for impulsive suicide attempts (53.4–61.4%), which is more likely than planned attempts to occur as of or after age of enlistment.

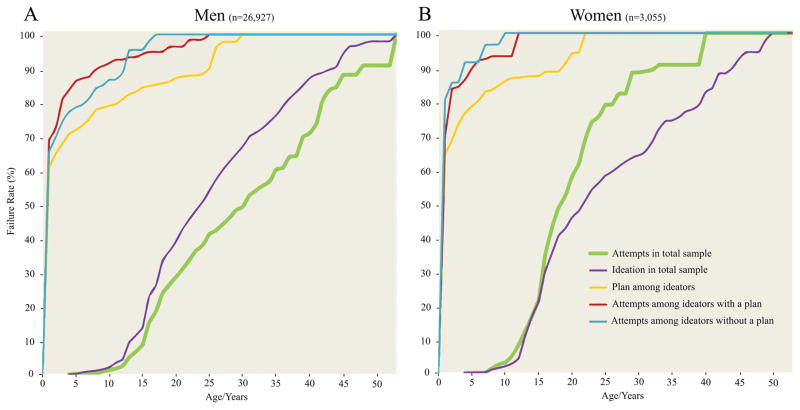

Additional insight into the timing of onset of suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts comes from inspection of age-of-onset (AOO) curves. (Figure 1) These curves have very similar shapes for males and females, with cumulative probability of onset of ideation and first attempts both quite low up to early adolescence, at which time cumulative risk rises sharply through the late teens and then increases with a reduced slope for males through the 30s and for females through the mid-20s and then decreases more at later ages. Another noteworthy consistency between the male and female AOO curves for ideation and attempts is that the two curves are closer to each other for both genders in adolescence than later ages, suggesting that the conditional probability of a first attempt among ideators is highest in adolescence. The speed-of-transition curves do not take this possible interaction into account, but rather look at aggregate transitions between first having suicide ideation and first making a suicide plan, first developing a plan and first making an attempt, and first having suicide ideation and first making an unplanned attempt. These transitions are uniformly very rapid, with 60–70% of plans and attempts occurring within the same year as the onset of the earlier phase of the transition.

Figure 1.

Age-of-onset and speed of transition curves for lifetime suicide ideation, attempts, plan among ideators, and attempts among those with and without a plan.

Note: Age of onset curves (i.e. ideation and attempt in the total sample) were measured starting at age 4 of life. Speed of transition curves (i.e. plan among ideators, attempts among ideators with and without a plan) were measured starting at the first year after ideation.

Joint associations of command, MOS, and rank with suicidality before and after enlistment

Based on the above results, we estimated a series of survival models in which we examined the joint associations of command, MOS, rank, and age (pre-enlistment versus post-enlistment) with first onset of suicidality adjusting for the AOO distributions in Figure 1. It is noteworthy that command, MOS, and rank can all change over time, but were defined as of the time of survey in these analyses. This means that suicidality both prior to and after enlistment were “predicted” by characteristics of service that in the majority of cases did not occur until after the onset of the “outcomes.” We used this approach in order to consider the possibility of unrecognized or unidentified factors leading to soldiers with prior suicidality subsequently ending up in different commands, MOSs, and ranks. Models were estimated separately for males and females. We also estimated models that combined males and females but found significant differences in associations by gender foreshadowed in Table 1 that justified focusing on gender-specific models (detailed results are available on request). We consequently focus on gender-specific models here. Whereas we estimated both additive models and models that included interactions of all other predictors with command, age, and both, the best-fitting model for suicide attempt was the one that included interactions with age but not command. The joint associations of the other predictors with first onset of suicide attempts were additive. This means, in particular, that the associations of MOS and rank with suicide attempts were not significantly different among Regular Army soldiers compared to soldiers in the G/R. This was true for both males and females.

Among males, the coefficients in the additive model in the total sample, where we ignored interactions with age, for the most part parallel the patterns seen previously in Table 1: a significantly elevated OR of suicide attempts among soldiers in the Regular Army versus the G/R (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.7–3.5) due to elevated odds of ideation in the total sample and attempts among planners. (Table 2) There is no significant association between command and unplanned attempts among ideators and, unlike in Table 1, there is no significant inverse association between being in the Regular Army and making plans among ideators. The time-varying coefficient for whether or not the soldier was yet enlisted also is non-significant (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.6–1.4), indicating that no significant disjunction occurs in the underlying age distribution with enlistment. Despite model fit improving when interactions were added for the associations of other predictors with age, command and rank both remain significant in separate models for first suicide attempts pre-enlistment and post-enlistment, with the only noticeable differences being more elevated ORs for both command and junior rank in the post-enlistment model than the pre-enlistment model. Disaggregation also shows a remarkable consistency of component associations between the pre-enlistment and post-enlistment models. For example, the relative-odds of planned, but not unplanned, attempts among ideators are significantly elevated for soldiers in the Regular Army versus G/R both before (OR 2.6 versus 0.6 for planned and unplanned attempts) and after (3.0 versus 1.1) enlistment. The only pre-post difference is a significantly decreased OR of plans among ideators pre-enlistment (0.6) that is non-significant post-enlistment (1.1).

Table 2.

Predictors of lifetime suicidality in male only sample, weighted analysis.

| Total sample (npersons =26,927) | Ideators (npersons=3,344) | Ideators with plan (npersons=1,168) | Ideators without plan (npersons=2,176) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Lifetime ideation | Lifetime attempt | Lifetime plan | Lifetime attempt | Lifetime attempt | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| (nperson-years=653,626) | (nperson-years=681,557) | (nperson-years=25,028) | (nperson-years=9,082) | (nperson-years=20,815) | |||||||

| Model number and included variables | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Model 1 (total) | Regular Army (vs. Guard-Reserve) | 1.9* | (1.5–2.4) | 2.5* | (1.8–3.5) | 0.7 | (0.5–1.1) | 2.8* | (1.8–4.3) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.6) |

| MOS: Combat arms (vs. Combat service support) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.2) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.5) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.3) | 1.4 | (0.9–2.2) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.8) | |

| MOS: Combat support (vs. Combat service support) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.2) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.5) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.5) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.6) | 1.1 | (0.6–1.9) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 0.3 | 0.76 | 0.8 | 0.45 | 0.4 | 0.68 | 2.2 | 0.12 | 0.0 | 0.96 | |

| Post-Enlistment (vs. Pre-) | 0.9 | (0.8–1.1) | 0.9 | (0.6–1.4) | 0.9 | (0.8–1.1) | 0.6* | (0.3–0.9) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.7) | |

| Rank: Junior (vs. Officer) | 1.8* | (1.4–2.1) | 4.6* | (2.6–8.1) | 1.2 | (0.7–2.0) | 3.0* | (1.6–5.7) | 2.9* | (1.2–6.9) | |

| Rank: Senior (vs. Officer) | 1.2 | (1.0–1.5) | 2.3* | (1.3–4.2) | 1.2 | (0.7–2.0) | 2.1* | (1.1–4.1) | 1.2 | (0.5–3.4) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 29.3* | <.001 | 23.9* | <.001 | 0.2 | 0.79 | 5.5* | 0.005 | 7.2* | <.001 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Model 2 (pre- enlistment) | Regular Army (vs. Guard-Reserve) | 1.6* | (1.2–2.1) | 1.7* | (1.0–2.8) | 0.6* | (0.4–1.0) | 2.6* | (1.4–4.9) | 0.6 | (0.2–1.8) |

| MOS: Combat arms (vs. Combat service support) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.3) | 1.3 | (0.8–2.0) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.4) | 1.4 | (0.7–2.8) | 1.3 | (0.6–2.7) | |

| MOS: Combat support (vs. Combat service support) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.3) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.5) | 1.0 | (0.5–1.9) | 1.2 | (0.6–2.5) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 0.8 | 0.46 | 0.5 | 0.63 | 0.0 | 0.99 | 0.8 | 0.46 | 0.3 | 0.76 | |

| Rank: Junior (vs. Officer) | 1.5* | (1.2–1.8) | 3.6* | (1.7–7.2) | 1.3 | (0.7–2.5) | 3.1* | (1.2–7.5) | 1.8* | (0.5–6.2) | |

| Rank: Senior (vs. Officer) | 1.3* | (1.0–1.5) | 2.3* | (1.1–4.7) | 1.5 | (0.8–3.0) | 2.0 | (0.8–5.0) | 0.9 | (0.2–3.7) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 9.8* | <.001 | 7.2* | <.001 | 0.7 | 0.49 | 3.1* | 0.046 | 2.4 | 0.10 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Model 2 (post- enlistment) | Regular Army (vs. Guard-Reserve) | 2.1* | (1.5–2.9) | 3.4* | (1.8–6.2) | 1.1 | (0.6–1.9) | 3.0* | (1.3–6.7) | 1.1 | (0.4–3.2) |

| MOS: Combat arms (vs. Combat service support) | 0.9 | (0.8–1.1) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.6) | 1.5 | (0.7–3.2) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.8) | |

| MOS: Combat support (vs. Combat service support) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.3) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.6) | 1.3 | (0.8–2.0) | 0.7 | (0.3–2.0) | 0.9 | (0.4–2.0) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 0.2 | 0.79 | 0.2 | 0.79 | 0.8 | 0.45 | 1.1 | 0.34 | 0.2 | 0.86 | |

| Rank: Junior (vs. Officer) | 1.8* | (1.2–2.6) | 5.0* | (2.2–11.5) | 1.4 | (0.8–2.3) | 3.7* | (1.4–9.7) | 6.0* | (2.0–17.6) | |

| Rank: Senior (vs. Officer) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.5) | 2.2 | (0.9–5.1) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.7) | 2.2 | (0.9–5.5) | 1.8 | (0.5–6.1) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 9.5* | <.001 | 14.9* | <.001 | 0.8 | 0.44 | 4.9* | 0.009 | 9.4* | <.001 | |

Note. Person-year interval variable OR’s were not reported.

As with males, the coefficients in the additive model in the total sample of females (Table 3), where we ignored interactions with age, for the most part parallel the patterns seen previously in Table 1: significantly elevated ORs of suicide attempts among junior and senior enlisted soldiers compared to officers (OR 3.8, 95% CI 2.0–7.3 junior; OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.2–3.9 senior) due to elevated odds of both planned and unplanned attempts among ideators but no significant elevations in either ideation or plans among ideators. As with men, the time-varying coefficient for whether or not the soldier was yet enlisted also is non-significant (OR 1.5, 95% CI 0.8–2.8), indicating that no significant disjunction occurs in the underlying age distribution with enlistment. Even though model fit improved when interactions were added for the associations of other predictors with age, rank remains the only significant predictor of both pre-enlistment and post-enlisted suicide attempts, but with the elevated relative-odds among junior enlisted soldiers versus officers much more pronounced after enlistment than before (7.3 versus 2.2). Disaggregation shows consistency of component associations between the pre-enlistment and post-enlistment models with the exception of a significantly elevated OR of ideation among junior enlisted soldiers versus officers in the post-enlistment model (2.0) but not the pre-enlistment model (0.9).

Table 3.

Predictors of lifetime suicidality in female only sample, weighted analysis.

| Total sample (npersons=3,055) | Ideators (npersons=575) | Ideators with plan (npersons=256) | Ideators without plan (npersons=319) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Lifetime ideation | Lifetime attempt | Lifetime plan | Lifetime attempt | Lifetime attempt | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| (nperson-years=71,451) | (nperson-years=75,871) | (nperson-years=3,949) | (nperson-years=1,783) | (nperson-years=2,972) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Model number and included variables | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Model 1 (total) | Regular Army (vs. Guard-Reserve) | 2.2* | (1.6–3.0) | 1.4 | (0.9–2.3) | 0.3* | (0.2–0.5) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.4) | 2.3 | (0.3–16.4) |

| MOS: Combat arms (vs. Combat service support) | 0.7* | (0.5–1.0) | 1.0 | (0.5–2.0) | 0.9 | (0.4–1.7) | 2.8 | (0.7–11.6) | 0.5 | (0.1–2.3) | |

| MOS: Combat support (vs. Combat service support) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.4) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.6) | 0.6 | (0.4–1.1) | 1.6 | (0.8–3.6) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.2) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 3.3* | 0.041 | 0.4 | 0.64 | 1.4 | 0.24 | 1.3 | 0.27 | 1.3 | 0.28 | |

| Post-Enlistment (vs. Pre-) | 0.7* | (0.6–0.9) | 1.5 | (0.8–2.7) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.3) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.7) | 2.6 | (0.8–8.6) | |

| Rank: Junior (vs. Officer) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.5) | 3.8* | (2.0–7.3) | 1.5 | (0.7–3.1) | 3.2* | (1.4–7.5) | 6.1* | (1.3–27.8) | |

| Rank: Senior (vs. Officer) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.3) | 2.2* | (1.2–3.9) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.5) | 2.6* | (1.0–6.8) | 4.3* | (1.0–18.1) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 0.5 | 0.63 | 7.8* | <.001 | 2.9 | 0.06 | 3.6* | 0.030 | 2.8 | 0.06 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Model 2 (pre- enlistment) | Regular Army (vs. Guard-Reserve) | 2.1* | (1.4–3.1) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.7) | 0.2* | (0.1–0.5) | 0.5 | (0.2–1.2) | 2960.0* | (417.0–20047.0) |

| MOS: Combat arms (vs. Combat service support) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.0) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.7) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.5) | 2.7 | (0.6–11.7) | 0.3 | (0.0–2.6) | |

| MOS: Combat support (vs. Combat service support) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.7) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.7) | 0.4* | (0.2–0.9) | 1.3 | (0.5–3.4) | 0.5 | (0.2–1.3) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 3.5* | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.62 | 2.8 | 0.06 | 0.9 | 0.41 | 1.3 | 0.27 | |

| Rank: Junior (vs. Officer) | 0.9 | (0.6–1.2) | 2.3* | (1.1–4.8) | 1.3 | (0.5–3.5) | 2.2 | (0.9–5.4) | 5.9 | (0.7–52.9) | |

| Rank: Senior (vs. Officer) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.4) | 2.3* | (1.0–5.4) | 0.7 | (0.3–2.0) | 2.5 | (0.7–8.2) | 13.9* | (1.9–102.0) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 0.7 | 0.50 | 2.3 | 0.10 | 2.5 | 0.09 | 1.5 | 0.23 | 3.9* | 0.022 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Model 2 (post- enlistment) | Regular Army (vs. Guard-Reserve) | 2.4* | (1.4–4.0) | 2.8 | (0.9–8.5) | 0.4* | (0.2–0.9) | 1.7 | (0.4–7.0) | 0.8 | (0.1–8.0) |

| MOS: Combat arms (vs. Combat service support) | 0.6 | (0.3–1.3) | 1.2 | (0.3–5.3) | 1.2 | (0.3–4.9) | 3.9 | (0.4–41.1) | 0.6 | (0.1–5.4) | |

| MOS: Combat support (vs. Combat service support) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.5) | 1.2 | (0.6–2.5) | 1.0 | (0.5–2.0) | 2.7 | (1.0–7.8) | 0.2 | (0.0–1.4) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 0.7 | 0.49 | 0.1 | 0.90 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 1.9 | 0.16 | 1.3 | 0.28 | |

| Rank: Junior (vs. Officer) | 2.0* | (1.2–3.4) | 7.3* | (2.1–26.0) | 2.4 | (0.9–6.5) | 12.4* | (1.6–99.1) | 7.3* | (1.4–37.2) | |

| Rank: Senior (vs. Officer) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.9) | 1.9 | (0.5–7.1) | 1.1 | (0.4–2.9) | 4.6 | (0.5–39.8) | 0.7 | (0.1–3.7) | |

| F(2,209), p-value | 4.1* | 0.018 | 6.1* | 0.003 | 2.6 | 0.08 | 2.9 | 0.06 | 5.0* | 0.008 | |

Note. Person-year interval variable OR’s were not reported.

DISCUSSION

There are four major limitations to this study. First, the relatively low AAS response rate and linkage rates limit the external validity of findings. Second, some respondents might have failed to report their suicidal thoughts or behaviors due to stigma (Zinzow et al., 2013), fear of breaches in confidentiality or other reasons. Failures to disclose suicidal behaviors might have been related to some of the predictors considered here (e.g., possibly higher non-disclosure among men, combat arms, officers), which could introduce bias in tests of association between predictors and outcomes. Third, retrospective AOO reports might have been biased. Fourth and finally, we examined only a limited set of Army characteristics as predictors of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Fourth, there may be cohort effects. For example, by examining risk factors across all ages, we might have obscured factors that increase risk of suicidal behaviors for soldiers that enlisted in the 1980’s and 1990’s but not those that enlisted in the 2000’s or vice versa. Fourth, there are several other factors (e.g. demographics) that could account for the associations in the current study. It is infeasible to test all possible interactions but future Army STARRS studies will continue to examine how different factors work together to increase suicide risk.

Within the context of these limitations, there are several noteworthy findings from this study. First, the overall prevalence estimates from the Consolidated AAS sample are consistent with those found by Nock et al. (2014) in an initial AAS sample that did not include deployed soldiers or members of the G/R. Also consistent with this prior report as well as large representative samples from the general population (Nock et al., 2008), women have higher rates than men of each suicidal outcome examined. For instance, women have nearly twice the lifetime prevalence of men for suicidal ideation (20.1% vs. 12.7%, respectively) and suicide attempts (5.1% vs. 2.5%, respectively). However, it should be noted that much of the increased risk of suicide attempts for women is accounted for by increased ideation.

Second, we found substantial pre-enlistment suicidal behaviors, suggesting that Army-related experiences (e.g. combat experiences) do not entirely account for suicidal behaviors in the Army. For example, the majority of nonfatal lifetime suicidal outcomes (e.g., 56–70% of lifetime ideation, attempts and suicide plans among those with ideation) experienced by Army soldiers had their first onset before the soldiers enlisted in the Army. Notably, these high rates of pre-enlistment suicidal outcomes also are directly consistent with prior studies of new soldiers reporting similar rates of pre-enlistment suicidal outcomes (Ursano, Heeringa, et al., 2015), and indirectly consistent with prior studies of new soldiers going through BCT (Nock et al., 2015; Rosellini et al., 2015) showing high rates of pre-enlistment mental disorders, which are strong predictors of subsequent suicidal behavior (Nock et al., 2014, 2015). Taken together, these findings show clearly that a substantial number of recruits elude the Army’s efforts to identify and reject applicants with pre-existing suicidal histories. Therefore, additional outreach and intervention efforts for soldiers may help reduce suicidal behaviors within the Army. Additionally, permitting soldiers with mental health difficulties or previous suicidal behaviors to join the Army may increase disclosure and provide the Army with information about which soldiers might require additional monitoring and intervention.

Third, we found that risk varied among difference career characteristics. For example, a new finding in this study is that soldiers in the Regular Army, compared to those in the G/R, have higher rates of suicide ideation (males and females) and attempts (males only). For men, the higher prevalence of suicide attempts among those in the Regular Army is accounted for by higher rates of both lifetime ideation and suicide attempts among those with a suicide plan and this was the case for during both pre- and post-enlistment. Future Army STARRS studies will explore associations with on-the-job experiences that may be associated with increased risk for suicide attempts and may help explain this finding. For women, those in the Regular Army show higher rates of suicidal ideation but similar rates of attempting suicide. This latter null result could be due to low statistical power, as only 15 women in the G/R attempted suicide. This overall finding of higher prevalence of ideation and attempts among Regular Army relative to G/R is partially consistent with prior studies on suicide death in the military in which Active Duty personnel across all branches showed higher rates of suicide death that those in Reserve and National Guard positions; however, the higher rates were not statistically significant (LeardMann, Powell, Smith, & et al, 2013). In contrast, it is inconsistent with a recent study that found that among new soldiers in BCT, G/R soldiers have higher rates of lifetime ideation and similar rates of lifetime attempts relative to those in the Regular Army (Ursano, Heeringa, et al., 2015). These inconsistent results could be due to differences between the types of G/R soldiers included in the present study (i.e., activated G/R soldiers of all ages) and those included in the study focused on BCT (i.e., new recruits). For example, G/R soldiers with a history of suicidal behaviors may be less likely to achieve (and remain at) active duty status (thus lowering the rate of suicide ideation and attempt among those captured in the current study). Future studies examining suicidal behavior among G/R at various stages of their Army career are needed to gain a clearer understanding of the prevalence, as well as risk and protective factors, of this group of servicemembers.

Fourth, along with being in the Regular Army, the other career characteristic significantly associated with suicidal behaviors is being in an enlisted rank, particularly a junior rank. Interestingly, enlisted soldiers and officers do not differ in the prevalence of suicide ideation or plans. Instead, these results showed that enlisted soldiers have higher rates of suicide attempts because they are more likely than officers to act on their suicidal thoughts or plans. Increased risk of suicidal behavior among enlisted soldiers is consistent with an earlier AAS paper (Nock, et al., 2014) and several other studies looking at suicidal behaviors and suicide death (Allen, Cross, & Swanner, 2005; Bachynski et al., 2012; Hyman, Ireland, Frost, & Cottrell, 2012; Schoenbaum et al., 2014; Skopp, Zhang, Smolenski, & Reger, 2016) as well as a prior study within the Regular Army that found that, compared with officers, enlisted troops had higher 30-day prevalence for nearly all internalizing and externalizing mental disorders (Kessler et al., 2014).

Fifth, the results suggest that Army-related experiences could not entirely account for the higher risk found in some careers. The two career characteristics with higher prevalence of suicidal outcomes – being in the Regular Army or being an enlisted soldier – showed elevated rates of increased risk both before and after joining the Army. This suggests that careers with higher prevalence of suicidal behaviors show this increased risk, at least in part, because people with pre-existing vulnerabilities select these careers. One possibility could be that people with externalizing disorders, which are associated with suicidal behaviors in the Army (Nock et al., 2014, 2015), are more likely to join the Regular Army or join in an enlisted rank. Future studies are needed to further investigate this possibility and to identify other possible explanations for this association.

Sixth, against expectations, we observed no increased risk of suicidal behaviors among those in combat-related occupations. This is inconsistent with prior studies reporting increased suicide death among combat arms occupations (Helmkamp, 1996; Kessler et al., 2015; LeardMann, Powell, Smith, & et al, 2013; Trofimovich et al., 2013), but consistent with a recent case-control study that found that, compared with troops in other occupations, those in combat-related occupations had a lower prevalence of suicide attempts and no greater risk of suicide death (Skopp et al., 2016). There are at least two explanations why these occupations would be associated with suicide death but not non-lethal suicidal behaviors. First, those in combat-related positions could be more likely to conceal prior suicidal behaviors because of cultural norms that include avoiding negative emotions or stimuli that produce them (Bryan, Stephenson, Morrow, Staal, & Haskell, 2014), withholding expressions of negative or difficult emotions (Jakupcak, Blais, Grossbard, Garcia, & Okiishi, 2014), and stigma associated with reporting mental health problems or using mental health services (Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, 2006; Zinzow et al., 2013). Second, combat arms soldiers may truly have similar rates of suicidal behaviors as other occupations but be more likely to act on suicidal thoughts with more lethal means, such as firearms (Shenassa, Catlin, & Buka, 2003), resulting in death.

Interestingly, women in combat arms occupations had lower odds of suicidal ideation than other women, an association not observed among men. Given the rigorous standards one must meet to be considered fit for these occupations (Servick, 2015), this reduced suicide risk may represent a resilience among women that select and meet the requirements for combat arms occupations, only a few of which were open to women at the time of the study. This finding does not conflict with the prior study examining suicide death among occupational specialty (Kessler et al., 2015) because that study did not examine suicide ideation and the two identified high-risk occupations were closed to women during the period of data collection. Additional well-powered studies are needed to further examine the risk and protective factors for suicidal behaviors among female soldiers.

This study provides new information about the prevalence of suicidal behaviors in the Army as well as about the role of Army history variables as risk and protective factors for suicidal behaviors. Future studies using this Consolidated AAS will examine a much broader set of potential risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior among Army soldiers. Taken together, this series of studies aims to improve the understanding, prediction, and prevention of suicidal behavior among Army soldiers.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions: Kessler had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Conception and design of Army STARRS: Ursano, Kessler; Conception and design of the data analysis plan for the current paper: Nock, Kessler, Millner; Acquisition of AAS data: Ursano, Kessler, Sampson; Analysis and interpretation of data: Kessler, Millner, Nock, Zaslavsky; Drafting of the manuscript: Millner, Nock, Kessler; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors; Statistical analysis: Hwang, King, Sampson. Zaslavsky; Obtaining funding: Ursano, Stein, Kessler; Administrative, technical, or material support: All authors; Supervision: Kessler, Nock, Sampson, Zaslavsky.

Financial Disclosure: In the past 3 years, Dr. Kessler received support for his epidemiological studies from Sanofi Aventis, was a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, and served on an advisory board for the Johnson & Johnson Services Inc. Lake Nona Life Project. Kessler is a co-owner of DataStat, Inc., a market research firm that carries out healthcare research. Dr Stein has been a consultant for Healthcare Management Technologies, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Tonix Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors report nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support: Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number U01MH087981 with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIMH, the Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense.

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors specified the topic in the RFP but had no role in the design of the study. However, as a cooperative agreement, collaborating scientists appointed to the project by NIMH and Army liaisons/consultants participated in the refinement of the study protocol originally proposed by Ursano, Kessler, and the other initial Army STARRS collaborators. None of the Army or NIMH collaborators was involved in planning or supervising data analyses for this report, but they did read a draft and offered suggestions for revision. Although a draft of this manuscript was submitted to the Army and NIMH for review and comment prior to submission, this was with the understanding that comments would be no more than advisory. Other than for the above, the funding organization played no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The STARRS-LS Collaborators: The Army STARRS Team consists of Co-Principal Investigators: Robert J. Ursano, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) and Murray B. Stein, MD, MPH (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System). Site Principal Investigators: Steven Heeringa, PhD (University of Michigan) and Ronald C. Kessler, PhD (Harvard Medical School). National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) collaborating scientists: Lisa J. Colpe, PhD, MPH and Michael Schoenbaum, PhD. Army liaisons/consultants: COL Steven Cersovsky, MD, MPH (USAPHC (Provisional)) and Kenneth Cox, MD, MPH (USAPHC (Provisional)). Other team members: Pablo A. Aliaga, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); COL David M. Benedek, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); K. Nikki Benevides, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul D. Bliese, PhD (University of South Carolina); Susan Borja, PhD (NIMH); Evelyn J. Bromet, PhD (Stony Brook University School of Medicine); Gregory G. Brown, PhD (University of California San Diego); Laura Campbell-Sills, PhD (University of California San Diego); Catherine L. Dempsey, PhD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Carol S. Fullerton, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Nancy Gebler, MA (University of Michigan); Robert K. Gifford, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Stephen E. Gilman, ScD (Harvard School of Public Health); Marjan G. Holloway, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul E. Hurwitz, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Sonia Jain, PhD (University of California San Diego); Tzu-Cheg Kao, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Karestan C. Koenen, PhD (Columbia University); Lisa Lewandowski- Romps, PhD (University of Michigan); Holly Herberman Mash, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James E. McCarroll, PhD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James A. Naifeh, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Tsz Hin Hinz Ng, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Matthew K. Nock, PhD (Harvard University); Rema Raman, PhD (University of California San Diego); Holly J. Ramsawh, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Anthony Joseph Rosellini, PhD (Harvard Medical School); Nancy A. Sampson, BA (Harvard Medical School); CDR Patcho Santiago, MD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Michaelle Scanlon, MBA (NIMH); Jordan W. Smoller, MD, ScD (Harvard Medical School); Amy Street, PhD (Boston University School of Medicine); Michael L. Thomas, PhD (University of California San Diego); Leming Wang, MS (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Christina L. Wassel, PhD (University of Vermont); Simon Wessely, FMedSci (King’s College London); Christina L. Wryter, BA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Hongyan Wu, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); LTC Gary H. Wynn, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); and Alan M. Zaslavsky, PhD (Harvard Medical School). Additional Information: A complete list of Army STARRS publications can be found at http://www.STARRS-LS.org.

References

- Allen JP, Cross G, Swanner J. Suicide in the Army: A Review of Current Information. Military Medicine. 2005;170:580–584. doi: 10.7205/milmed.170.7.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 6. Deerfield, IL: American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bachynski KE, Canham-Chervak M, Black SA, Dada EO, Millikan AM, Jones BH. Mental health risk factors for suicides in the US Army, 2007–8. Injury Prevention. 2012;18:405–412. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SA, Gallaway MS, Bell MR, Ritchie EC. Prevalence and risk factors associated with suicides of Army soldiers 2001–2009. Military Psychology. 2011;23:433. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Stephenson JA, Morrow CE, Staal M, Haskell J. Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Work-Related Accomplishment as Predictors of General Health and Medical Utilization Among Special Operations Forces Personnel. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2014;202:105–110. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Logistic Regression, Survival Analysis, and the Kaplan-Meier Curve. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1988;83:414–425. [Google Scholar]

- Gadermann AM, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, et al. Classifying U.S. Army Military Occupational Specialties Using the Occupational Information Network. Military Medicine. 2014;179:752–761. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Bromet EJ, Cox KL, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Gruber MJ, et al. Sociodemographic and career history predictors of suicide mortality in the United States Army 2004–2009. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44:2579–2592. doi: 10.1017/S003329171400018X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith J. Army suicides: “knowns” and an interpretative framework for future directions. Military Psychology. 2012;24:488–512. [Google Scholar]

- Gubata ME, Piccirillo AL, Packnett ER, Cowan DN. Military Occupation and Deployment: Descriptive Epidemiology of Active Duty U.S. Army Men Evaluated for a Disability Discharge. Military Medicine. 2013;178:708–714. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halli SS, Rao KV. Advanced techniques of population analysis. New York, NY: Plenum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Helmkamp JC. Occupation and suicide among males in the US armed forces. Annals of Epidemiology. 1996;6:83–88. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(95)00121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to iraq or afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295:1023–1032. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman J, Ireland R, Frost L, Cottrell L. Suicide Incidence and Risk Factors in an Active Duty US Military Population. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:S138–S146. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Blais RK, Grossbard J, Garcia H, Okiishi J. “Toughness” in association with mental health symptoms among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking Veterans Affairs health care. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2014;15:100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Gebler N, Hwang I, et al. Response bias, weighting adjustments, and design effects in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2013;22:288–302. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Hwang I, et al. Thirty-day prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among nondeployed soldiers in the US Army: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:504–513. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Stein MB, Bliese PD, Bromet EJ, Chiu WT, Cox KL, et al. Occupational differences in US Army suicide rates. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45:3293–3304. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirin SJ, Winkler JD. The Army Military Occupational Specialty Database. DTIC Document. 1992 Retrieved from http://oai.dtic.mil/oai/oai?verb=getRecord&metadataPrefix=html&identifier=ADA428376.

- Kuehn BM. Soldier suicide rates continue to rise. JAMA. 2009;301:1111–1113. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne M, Naftel S, Thie HJ, Kawata JH. Military Occupational Specialties. RAND Corporation; 2001. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monograph_reports/2009/MR977.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- LeardMann CA, Powell TM, Smith TC, Bell MR, Smith B, Boyko EJ, et al. Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former us military personnel. JAMA. 2013;310:496–506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.65164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom KE, Smith TC, Wells TS, Wang LZ, Smith B, Reed RJ, et al. The Mental Health of U.S. Military Women in Combat Support Occupations. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15:162–172. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebuhr DW, Krampf RL, Mayo JA, Blandford CD, Levin LI, Cowan DN. Risk factors for disability retirement among healthy adults joining the US Army. Military Medicine. 2011;176:170–175. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Deming CA, Fullerton CS, Gilman SE, Goldenberg M, Kessler RC, et al. Suicide Among Soldiers: A Review of Psychosocial Risk and Protective Factors. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2013;76:97–125. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2013.76.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Stein MB, Heeringa SG, Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Suicidal Behavior Among Soldiers: Results From the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:514. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Ursano RJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, Jain S, Raman R, et al. Mental Disorders, Comorbidity, and Pre-enlistment Suicidal Behavior Among New Soldiers in the U.S. Army: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2015;45:588–599. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger MA, Smolenski DJ, Skopp NA, Metzger-Abamukang MJ, Kang HK, Bullman TA, et al. RIsk of suicide among us military service members following operation enduring freedom or operation iraqi freedom deployment and separation from the us military. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:561–569. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosellini AJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, Ursano RJ, Chiu WT, Colpe LJ, et al. Lifetime Prevalence of DSM-IV Mental Disorders Among New Soldiers in the U.S. Army: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (army Starrs) Depression and Anxiety. 2015;32:13–24. doi: 10.1002/da.22316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum M, Kessler RC, Gilman SE, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, et al. Predictors of Suicide and Accident Death in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS): Results From the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:493. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servick K. Setting the bar. Science. 2015;349:468–471. doi: 10.1126/science.349.6247.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenassa ED, Catlin SN, Buka SL. Lethality of firearms relative to other suicide methods: a population based study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:120–124. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skopp NA, Zhang Y, Smolenski DJ, Reger MA. Risk factors for self-directed violence in US Soldiers: A case-control study. Psychiatry Research. 2016;245:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trofimovich L, Reger MA, Luxton DD, Oetjen-Gerdes LA. Suicide Risk by Military Occupation in the DoD Active Component Population. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2013;43:274–278. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB. The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2014;77:107–119. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, Jain S, Raman R, Sun X, et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among new soldiers in the U.S. Army: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Depression and Anxiety. 2015;32:3–12. doi: 10.1002/da.22317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Cox KL, Naifeh JA, Fullerton CS, et al. Nonfatal Suicidal Behaviors in U.S. Army Administrative Records, 2004–2009: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Psychiatry. 2015;78:1–21. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2015.1006512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Stein MB, Naifeh JA, Aliaga PA, Fullerton CS, et al. Suicide attempts in the US Army during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, 2004 to 2009. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:917–926. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter KM. Introduction to variance estimation. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Britt TW, Pury CLS, Raymond MA, McFadden AC, Burnette CM. Barriers and facilitators of mental health treatment seeking among active-duty army personnel. Military Psychology. 2013;25:514–535. [Google Scholar]