Abstract

The biodegradable elastomeric polyester poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS) was developed for soft-tissue engineering. It has been used in various research applications such as wound healing, cartilage tissue engineering, and vascular grafting due to its biocompatibility and elastomeric properties. However conventional PGS manufacture is generally limited by the laborious reaction conditions needed for curing which requires elevated reaction temperatures, high vacuum and multi-day reaction times. In this study, we developed a microwave irradiation methodology to fabricate PGS scaffolds under milder conditions with curing times that are 8 times faster than conventional methods. In particular, we determined microwave reaction temperatures and times for maximum crosslinking of PGS elastomers, demonstrating that PGS is fully crosslinked using gradual heating up to 160 °C for 3 h. Porosity and mechanical properties of these microwave-cured PGS elastomers were shown to be similar to PGS elastomers fabricated by the conventional polycondensation method (150°C under 30 Torr for 24 h). To move one step closer to clinical application, we also examined the biocompatibility of microwave-cured PGS using in vitro cell viability assays with primary baboon arterial smooth muscle cells (SMCs). These combined results show microwave curing of PGS is a viable alternative to conventional curing.

Keywords: poly(glycerol sebacate), biodegradable polyester, vascular graft, microwave, polycondensation

Introduction

Poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS) elastomer has been used in tissue engineering and drug delivery due to its biodegradability and tunable mechanical properties [1-3]. In our previous work, porous, degradable PGS scaffolds were designed to provide facile cell infiltration with the capability to replace and regenerate injured or diseased tissues in a variety of applications which include small-diameter blood vessels, bone and nerves [4-16].

PGS is a thermoset polyester that has been synthesized mostly by a polycondensation process based on Fischer-Speier esterification. Hydroxyl groups of glycerol react with the carboxylic acid groups of sebacic acid while releasing water molecules [1, 17, 18]. The advantage of this material is that the monomers (sebacic acid and glycerol), the intermediate (PGS oligomers), and the final polymers, all have good biocompatibility. Most applications using PGS require a curing step to convert PGS from a sticky resin to an elastomer. However, this process is difficult to scale up because of prolonged heating (120-150°C), high vacuum (less than 25 Torr) and several days of reaction time [1, 18].

To overcome the limitations of the time and energy-consuming fabrication method, alternative methods and new polymer compositions have been studied. Nijst and co-workers fabricated ultraviolet (UV) curable PGS elastomers incorporating acrylic moieties as a photo reactive co-monomer in poly(glycerol sebacate)acrylate (PGSA) [19]. UV irradiation triggered crosslinks between the acrylate units at room temperature in the presence of an initiator. On the other hand, the crosslinking between non-photoreactive components such as esterification of sebacic acid and glycerol did not occur. This change of crosslinking mechanism induced significant modifications of the stiffness and degradation rates of the final elastomer. Aydin et al. recently demonstrated that PGS prepolymer can be prepared via microwave irradiation to reduce reaction time without a purging process [20]. However, the resultant PGS has low glycerol content, i.e. the molar ratio of glycerol:sebacic acid is 22:78 and the mechanical properties of the elastomer were different from PGS elastomer with 1:1 monomer ratio. Moreover, the crosslinking step was still long, requiring at least 16 h of microwave irradiation.

Here we report a fast and facile PGS scaffold fabrication method using microwave polymerization that increases the curing speed while maintaining the physical and mechanical properties of the classic PGS elastomer. We refer to microwaved cured PGS as mwPGS and conventionally cured ones as cPGS. Microwave polymerization has become a useful synthesis method because of its ability to accelerate the reaction with high yield while reducing the amount of solvent and catalysts. Compared to conventional heating methods, microwave-assisted processing is not as thoroughly understood. There is a dearth of information on the reaction mechanism induced by microwave irradiation which makes it difficult to predict or control the reaction inside the sample. Herein, we focused on controlling the curing process of PGS resin by applying different microwave irradiation intensities (or reaction temperatures) to define a suitable reaction condition to obtain highly crosslinked PGS elastomer. Conditions were identified for fabricating porous PGS tubes suitable for vascular grafting using significantly shorter reaction times and without purging gases, vacuum, or catalysts. The morphological and mechanical properties and in vitro biocompatibility of these tubes support the suitability of these tubes for vascular grafting.

Materials and Methods

1. Fabrication of the scaffold

Poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS) prepolymer was synthesized in house as described previously[1]. Tubular scaffolds for vascular grafts were fabricated using a solvent casting and salt leaching method with 25-32 μm grounded salts as porogens [5]. Briefly, salts were packed into the mold that consisted of a stainless steel rod (outer diameter = 0.8 mm) was used as a mandrel and placed into a Teflon® tube (inner diameter = 1.58 mm, length = 20 mm) as a mold. Salts were filled into the space between the tube and mandrel by pushing the assembled mold into salts in a glass vial. Filled salts were pressed by two hollow plungers (outer diameter = 1.55 mm, inner diameter = 0.82 mm) from both ends of the mold to pack salts densely while keeping the mandrel centered. The salt tubes were made by pulling the mandrel out from the packed salts using pliers. Salt-packed molds were placed in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 90 min to fuse salts together. The salt tube were released from the mold by pushing one end with a stainless steel rod (outer diameter = 1.5 mm). PGS prepolymer was dissolved with tetrahydrofuran (THF) to prepare 20 weight/volume % solution. The volume of PGS solution was adjusted as 3:1 mass ratio of salt:PGS and added to the salt tubes which were then placed in a fume hood for 1 h to evaporate the solvent.

Conventional thermal curing method (cPGS)

PGS infused salt tube was placed in a vacuum oven with gradual heating to 150°C under 30 Torr vacuum for 24 h. Microwave-assisted curing method (mwPGS): Each salt mold loaded with 20 wv% PGS prepolymer solutions in THF was placed in a microwave vial with silica desiccant (approximately 1.5 g per vial) and cured in the microwave reactor (Biotage® Initiator, Charlotte, NC) under varying reaction temperature conditions of 120, 140, 160 and 170°C for 3 h. The reaction temperature was reached through gradual heating at a rate of 10°C/min from the starting temperature of 100°C. After completion of the curing process, salt molds were dissolved in a series of two 10 mL water baths (first bath for 24 h and second bath for 48 h). The final grafts were lyophilized before further examination.

2. Characterization of the scaffold

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Thermal properties of PGS scaffolds were recorded using a Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) (Q200, TA Instruments, New Caste, DE), following a cycle of heating/cooling/heating under nitrogen atmosphere with a heating range from 25°C to 150°C and cooling to -50°C with scanning rate of 10°C/min.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR spectra were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet iS10 spectrometer equipped with a diamond Smart iTR.

Scanning electron microscopy

The structure of porous PGS scaffolds was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). PGS scaffolds were cut into 2 mm segments transversely, mounted onto aluminium stubs with carbon tape, sputter-coated with gold, and observed with a field emission SEM (6330F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

X-ray Micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT)

Porosity and pore size distribution of grafts were measured using X-ray micro-computed tomography (micro-CT). PGS vascular grafts (10 mm long) were mounted in polystyrene foam tubes affixed to a brass stub and scanned using the submicron (0.35 μm) resolution micro-CT (Skyscan 1272, Bruker Corp., Billerica, MA) with the following settings: average camera pixel size = 7.4 μm, image pixel size = 2.53 μm, frame averaging of 10, rotation step size of 0.1 degrees, scanned 180 degrees around the vertical axis. Three-dimensional (3D) images were reconstructed as a stack of 2 μm thick sections in the axial plane using the reconstruction software (NRecon, Bruker Corp.). Porosity and pore size distribution were calculated using the morphometric analysis software (CTAn, Bruker Corp.) by thresholding the sample in the region of interest followed by despeckling and 3D analysis.

Mechanical testing

Mechanical properties of porous PGS scaffolds (n=4 each) were examined using uniaxial tensile testing as described in [21, 22]. Uniaxial testing was conducted since the PGS core was assumed to be isotropic due to the nature of fabrication process in which pores are distributed uniformly across the radius and length of the graft. Namely, there is no preferential alignment of material fibers or grains. The scaffold dimensions were length of 9.62 ± 0.36 mm, outer diameter of 1.51 ± 0.02 mm and wall thickness of 330 um ± 20 um. Briefly, scaffolds were sutured on cannulae and placed in a custom-designed mechanical testing device for tubular structures. Axial stretch was applied at a controlled strain-rate via a computer-controlled 176 actuator (Aerotech Inc., Model ANT-25LA) at 37°C under a video-camera (Edmund Optics, Model EO-177 5012C), providing images that were post processed to obtain local strain. Five preconditioning cycles were performed by subjecting the sample to 10% strain at a strain rate of 0.005 mm/sec followed by stretching the samples to failure. Both the ultimate tensile stress and tensile modulus were obtained from the Cauchy stress-strain curve for each sample. The tensile modulus was obtained from the high strain (>20%) region of the stress-strain curve using a linear curve-fit in the region with an R2 > 0.98 for each curve.

3. In vitro cell viability assays

Cell isolation and culture

Primary arterial smooth muscle cells (SMCs) were isolated from the carotid arteries of juvenile male baboons (Papio Anubis) and characterized in two-dimensional culture before passaging and seeding [23]. SMCs were expanded using the MCDB 131 medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), 1% L-glutamine (Mediatech), and an antibiotic-antimycotic solution (100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 mg/mL amphotericin B; Mediatech).

LIVE/DEAD assay

The cytotoxicity testing was performed by the extraction method according to ISO 10993-5 and using LIVE/DEAD kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The porous mwPGS and cPGS films (n = 7 each) of 3 cm (length) × 2 cm (width) × 0.2 cm (thickness) were extracted at 37°C for 24 h in MCDB culture medium (3 cm2/mL) respectively. Baboon SMCs at passage 7 were cultured at 37°C in MCDB medium at about 70 % of confluency, approximately every 3 days. Then, cells were transferred into a 96-well plate at 10,000 cells/well. After allowing cells 24 h to be attached, the culture media were exchanged for 200 μL of freshly prepared extraction media. Incubation of cells in basal culture medium was used alongside as a positive control. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h, the cells were washed with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, Mediatech), and then stained with a 100 μL solution of DPBS containing approximately 2 μM calcein AM (5 μL) and 4 μM ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1) (20 μL) solution. Fluorescent images of live and dead SMCs were taken in the FITC (calcein AM) and TRITC (EthD-1) channels after 30 min incubation at room temperature using an inverted microscope (Eclipse Ti-E, Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). The numbers of live and dead cells were counted in each of 7 wells per sample group using the image analysis software (NIS-Element, Nikon).

CellTiter-Blue assay

In vitro cell viability was quantified using CellTiter-Blue assay (Promega, Madison, WI). Baboon SMCs (passage 7) cultured by the above-mentioned cell-culture preparation were seeded in 96 well-plate at 10 000 cells/well (n = 7/each group). After 24 h incubation at 37°C, cells were treated with 20 μL blue assay solution (resazurin) per 100 μL medium (120 μL in total), then incubated for an additional 4 h at 37°C. Fluorescence intensity of blue treated cells was measured by Synergy™ Mx microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT) at the emission of 590 nm upon excitation at 560 nm.

4. Statistical Analyses

All data are reported as means ± standard deviations of n = 4 for each mwPGS and conventionally cured cPGS for tensile tests, and n = 7 (each) for cell viability tests. Welch's t-test was performed using GraphPad Prism 7 Software (La Jolla, CA) to assess the statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

1. Microwave assisted PGS scaffold fabrication

Throughout this work, we prepared all PGS elastomers using PGS prepolymers that were synthesized in-house with a molar ratio of 1:1 for sebacate:glycerol following our previous work [6]. Porous PGS tubes were fabricated following Scheme 1. using the salt tube mold. After the completion of polymer curing by thermal route or microwave irradiation, final porous PGS grafts were obtained by dissolving salts in water for 48 h.

Scheme 1. Illustration of fabrication steps of porous PGS scaffold for small arterial grafting.

Water removal from the esterification between glycerol and sebacic acid is the driving force to obtain the maximum intra/inter molecular reaction between two crosslinking moieties. The crosslinking of PGS by conventional thermal curing technique requires high temperature (150 ± 30°C) and increased water removal upon application of high vacuum (25- 30 Torr). In contrast, in the microwave-assisted curing technique, we set reaction temperatures from 120 to 170°C (with a gradual heating of 10°C/min) without vacuum for water removal. Water was immediately removed by the desiccant in the reaction vial.

In the literature, the melting points (Tm) of sebacic acid and glycerol were reported respectively in the range of 130-133°C and 16-18°C, and fully cured PGS has a glass transition temperature about -37 to -5°C and an endothermic peak between 0-15°C according to the monomer ratio[24, 25]. We monitored curing states of PGS elastomers based on the progression of their thermal properties using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (Figure 1). Thermal properties of mwPGS changed as the reaction temperature varied from 120°C to170°C (or microwave reactor power from 60 W to 110 W) for 3 h. The mwPGS sample cured at 170°C was burnt during microwave irradiation because of excessively high temperatures, therefore we didn't proceed with this condition. In Figure 1A, the DSC curves of mwPGS cured at 120°C, 140°C, and 160°C (with heating rates of 10°C/min) were plotted with the curves of non-cured PGS prepolymer and cPGS, cured at 150°C under 30 Torr for 24 h. PGS prepolymer was reported to have two endothermal peaks at 10.7°C and at 27.80°C respectively for sebacic acid and glycerol units in the chain. No traces of Tm of monomers were observed in DSC data as all monomers were removed by purification process during prepolymer preparation. The thermogram of mwPGS cured at 120°C for 3 h showed that the polymer was not fully cured since it had a thermogram similar to that of PGS prepolymer. A decrease of endothermic peak at 27.8°C and an appearance of two glass transition temperature transitions at -27.5°C and -11°C were progressively observed with an increase of reaction temperature up to 160°C and reaction time up to 3h. During the cooling cycle, we observed a recrystallization peak of PGS prepolymer at -20°C. This peak was also shifted to - 24°C for cPGS and mwPGS cured at 160°C.

Figure 1.

(A) Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms showing heating cycle of PGS at different curing temperatures and processing methods: curves represented respectively PGS prepolymer, PGS cured in microwave at 120°C, 140°C, and 160°C for 3 h (mwPGS), and PGS cured in the oven at 150°C for 24 h under 30 Torr vacuum atmosphere (cPGS). (B) Comparison between DSC curves of cPGS (with vacuum) and mwPGS (without vacuum) cured at 160°C for 3 h. All DSC curves were recorded 1st heating from 25°C to 150°C, 1st cooling to -50°C, and 2nd heating to 160°C with heating rate of 10°C/min under nitrogen atmosphere.

The characteristic functional groups of PGS were additionally analysed by FTIR spectroscopy. PGS prepolymer and cured PGS by either curing method have similar FTIR spectra. We observed a peak at 1416.41cm–1, which was attributed to the O–H bending mode while the O-H stretch was observed as a broad peak at 3467.49 cm-1. Peaks at 2927.21 and 2853.97 cm–1 were attributed to alkene (–CH2) groups. Two pronounced peaks at 1159.36 and 1732.46 cm–1 were attributed to O–C=O and C=O, respectively. Quantitative analysis to check the crosslinking density of PGS was not performed since the O-H peak was too broad to measure the integral precisely.

In order to compare microwave with desiccant and conventional curing, the optimized microwave irradiation curing condition was applied to thermal curing. The PGS sample was processed in a vacuum oven at 160°C for 3 h at 30 Torr (Figure 1B). The results showed that the PGS cured in the oven was not fully crosslinked, the endothermic peak of prepolymer was still present and the glass transition temperature of the elastomer was not distinct on DSC. The thermal properties demonstrated that porous PGS scaffolds were completely cured after 3 h of microwave irradiation at 160°C, which was 8 times faster than conventional curing technique.

2. Physical properties of the PGS scaffolds

SEM images of the cross-section surface morphology of cured PGS grafts displayed both large and small pores (1-80 μm) with little difference between the two types of scaffolds (Figure 2A). In order to assess the morphology of the scaffolds, we measured their porosity and pore size distribution using micro-CT scanning and 3D image analysis. Most pores in both PGS scaffolds were in the range of 25-35 μm which was directly correlated to the salt size (25-32 μm) (Figure 2B). For cPGS, the pore distribution spread broadly from 1 to 80 μm, whereas for mwPGS the pores size was concentrated between 15-25 μm. The porosity of mwPGS and cPGS, based on total pore volume calculations, were 77.2 ± 1.92 % and 74.2 ± 3.66 %, respectively with no statistically significant difference between them (p = 0.322). The spread of pore size distribution (1-80 μm for cPGS and 1-50 μm for mwPGS) is due to the water evaporation and the interconnection formed between salt crystals during the fusion process. We hypothesize that the application of high vacuum for cPGS curing process induced the formation of large size pores (over 50 μm) since we observed large pores only in cPGS samples. A narrower pore distribution was observed in mw PGS samples as the total volume of pores in mwPGS was similar to cPGS, but the average pore size of mwPGS was reduced. This is likely attributable to the more homogenous microwave irradiation compared with the more pronounced temperature gradient in conventional heating in an oven.

Figure 2.

(A) SEM cross- section images of cPGS (left) and mwPGS (right). (B) 3D reconstructions of micro-CT scanning of PGS scaffolds. PGS elastomer is represented in red and pores (empty space) in green. The pore size distribution are reported as a percentage of pore volume and ranged between 0-90 μm. (C) Cauchy stress-strain curves for the PGS scaffolds with the corresponding ultimate tensile stress (UTS) and elastic moduli (n = 4, p > 0.05).

We examined the mechanical properties of both PGS scaffolds using uniaxial tensile test. The tensile modulus for mwPGS was 132 ± 26.75 kPa and for cPGS was 143 ± 29.02 kPa. The ultimate tensile strength values for mwPGS and cPGS were 78 ± 10.23 kPa, and 66 ± 7.67 kPa, respectively (Figure 2C). These values for UTS and tensile modulus for the mwPGS and cPGS were not significantly different (p = 0.391 and 0.782, respectively).

The tensile modulus of PGS is dependent on fabrication conditions, especially the molar ratio of glycerol and sebacic acid and curing temperatures. For the fabrication conditions used in this study, the high strain modulus of both cPGS and mwPGS scaffolds are similar to those reported in our previous study on mature elastin synthesis by culturing baboon smooth muscle cells in porous PGS scaffolds [5].

3. Biocompatibility

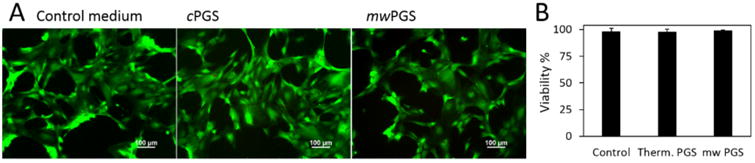

In order to further test the suitability of mwPGS as vascular grafting material, we examined its cytotoxicity qualitatively using LIVE/DEAD assay with primary baboon arterial smooth muscle cells (SMCs). Fluorescent images from LIVE/DEAD assay show mostly live SMCs in all three groups without significant presence of dead cells (Figure 3A). Moreover, we quantified the cell viability of mwPGS using CellTiter-Blue assay. As shown in Figure 3B, there were no statistically significant differences in percent cell viability among the three groups. These results indicate that mwPGS has the same cytocompatibility as the controls.

Figure 3.

(A) Representative fluorescent images of LIVE/DEAD-stained primary baboon SMCs which were cultured over 24 h in intact culture medium, extracts of mwPGS and cPGS.(n = 7) (B) Percentage of cell viability was determined by cell quantification assay using CellTiter-Blue assay (n = 7, p > 0.05).

Conclusion

We have developed a fabrication method for porous PGS scaffolds via microwave assisted curing that is 8 times faster than the conventional curing process and does not require vacuum. In this methodology, curing is achieved through gradual heating to 160°C for 3 h using a microwave reactor, The resultant scaffolds display similar porosity and mechanical properties to conventional PGS scaffolds. These scaffolds also preserved their biocompatibility. These results show that microwave curing of PGS is a viable alternative to conventional curing.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01HL 089658 and 1R21HL124479-01.

References

- 1.Wang YD, Ameer GA, Sheppard BJ, Langer R. A tough biodegradable elastomer. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:602–606. doi: 10.1038/nbt0602-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pego AP, Poot AA, Grijpma DW, Feijen J. Biodegradable elastomeric scaffolds for soft tissue engineering. J Control Release. 2003;87:69–79. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruggeman JP, de Bruin BJ, Bettinger CJ, Langer R. Biodegradable poly(polyol sebacate) polymers. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4726–4735. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasseri BA, Pomerantseva I, Kaazempur-Mofrad MR, Sutherland FWH, Perry T, Ochoa E, Thompson CA, Mayer JE, Oesterle SN, Vacanti JP. Dynamic rotational seeding and cell culture system for vascular tube formation. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:291–299. doi: 10.1089/107632703764664756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee KW, Stolz DB, Wang YD. Substantial expression of mature elastin in arterial constructs. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2705–2710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017834108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu W, Allen RA, Wang YD. Fast-degrading elastomer enables rapid remodeling of a cell-free synthetic graft into a neoartery. Nat Med. 2012;18:1148. doi: 10.1038/nm.2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeong CG, Hollister SJ. A comparison of the influence of material on in vitro cartilage tissue engineering with PCL, PGS, and POC 3D scaffold architecture seeded with chondrocytes. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4304–4312. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KW, Johnson NR, Gao J, Wang YD. Human progenitor cell recruitment via SDF-1 alpha coacervate-laden PGS vascular grafts. Biomaterials. 2013;34:9877–9885. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guler S, Hosseinian P, Aydin HM. Hybrid Aorta Constructs via In Situ Crosslinking of Poly(glycerol-sebacate) Elastomer Within a Decellularized Matrix. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods. 2016;23:21–29. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2016.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webb AR, Yang J, Ameer GA. Biodegradable polyester elastomers in tissue engineering. Expert Opin Biol Th. 2004;4:801–812. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.6.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaky S, Gao J, Lee K, Almarza A, Wang Y, Sfeir C. Poly (glycerol sebacate) Elastomer Supports Bone Regeneration by Its Mechanical Properties Similar to Osteoid Tissue. Tissue Eng Pt A. 2014;20:S7–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaky SH, Lee KW, Gao J, Jensen A, Verdelis K, Wang Y, Almarza AJ, Sfeir C. Poly (glycerol sebacate) Elastomer Supports Bone Regeneration by Its Mechanical Properties Being Closer to Osteoid Tissue Rather than to Mature Bone. Acta Biomater. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen R, Stowell C, Tillman B, Breuer C, Wang Y. In situ tissue engineering of arteries: the regeneration of nerve and the formation of elastic fibers. J Tissue Eng Regen M. 2014;8:202–202. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagandora CK, Gao J, Wang Y, Almarza AJ. Poly (glycerol sebacate): a novel scaffold material for temporomandibular joint disc engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:729–37. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadlock T, Sundback C, Hunter D, Cheney M, Vacanti JP. A polymer foam conduit seeded with Schwann cells promotes guided peripheral nerve regeneration. Tissue Eng. 2000;6:119–127. doi: 10.1089/107632700320748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeffries EM, Wang YD. Incorporation of parallel electrospun fibers for improved topographical guidance in 3D nerve guides. Biofabrication. 2013;5 doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/5/3/035015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrett DG, Yousaf MN. Design and Applications of Biodegradable Polyester Tissue Scaffolds Based on Endogenous Monomers Found in Human Metabolism. Molecules. 2009;14:4022–4050. doi: 10.3390/molecules14104022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu QY, Tian M, Ding T, Shi R, Feng YX, Zhang LQ, Chen DF, Tian W. Preparation and characterization of a thermoplastic poly(glycerol sebacate) elastomer by two-step method. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;103:1412–1419. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nijst CLE, Bruggeman JP, Karp JM, Ferreira L, Zumbuehl A, Bettinger CJ, Langer R. Synthesis and characterization of photocurable elastomers from poly(glycerol-co-sebacate) Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:3067–3073. doi: 10.1021/bm070423u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aydin HM, Salimi K, Rzayev ZMO, Piskin E. Microwave-assisted rapid synthesis of poly(glycerol-sebacate) elastomers. Biomater Sci-Uk. 2013;1:503–509. doi: 10.1039/c3bm00157a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gade PS, Lee KW, Wang Y, Robertson AM. Experimental methods to drive a computational growth and remodeling framework for in situ tissue engineered vascular grafts. 2017 Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gade PS, Lee KW, Wang Y, Robertson AM. Degradation and Erosion Mechanisms of Bioresorbable Porous Acellular Vascular Grafts: An In Vitro Investigation. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2017.0102. In Revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao J, Ensley AE, Nerem RM, Wang YD. Poly(glycerol sebacate) supports the proliferation and phenotypic protein expression of primary baboon vascular cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;83a:1070–1075. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai W, Liu LL. Shape-memory effect of poly (glycerol-sebacate) elastomer. Mater Lett. 2008;62:2171–2173. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rai R, Tallawi M, Grigore A, Boccaccini AR. Synthesis, properties and biomedical applications of poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS): A review. Prog Polym Sci. 2012;37:1051–1078. [Google Scholar]