Abstract

An estimated 35-68% of new HIV infections among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBM) are transmitted through main partnerships. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is highly effective in reducing HIV seroconversion, yet PrEP uptake has been modest. PrEP-naïve GBM with HIV-negative, PrEP-naïve main partners enrolled in One Thousand Strong (n=409), a U.S. national cohort of GBM, were asked about 1) the importance of partner PrEP use and 2) their willingness to convince their partner to initiate PrEP. On average, participants thought partner PrEP was only modestly important and were only moderately willing to try to convince their partner to initiate PrEP. Personal PrEP uptake willingness and intentions were the strongest indicators of partner PrEP outcomes. Being in a monogamish relationship arrangement (as compared to a monogamous arrangement) and the experience of intimate partner violence victimization were associated with increased willingness to persuade a partner to initiate PrEP.

Keywords: pre-exposure prophylaxis, men who have sex with men, same-sex couples, couples interdependence theory, intimate partner violence

Introduction

In the United States (U.S.), more than 1.2 million people are living with HIV, with about 44,000 new infections a year [1]. Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBM) account for an estimated 84% of new infections among males in the U.S. [1], and an estimated 32-68% of these new HIV infections occur through main partnerships [2, 3]. In 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) approved the use of a pre-exposure prophylactic (i.e., PrEP) combination pill of tenofovir, disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine for daily use in individuals at high risk for HIV [4]. Since FDA approval, further review of PrEP in open-label demonstration projects (i.e., all enrolled patients receive the active drug) found high levels of PrEP effectiveness. No new HIV infections were found in one sample composed mostly of GBM followed over 338 person years [5], and only two new HIV infections were observed in another study of 557 GBM and transgender women [6]. However, both individuals who seroconverted to HIV-positive had biological markers consistent with poor adherence of fewer than two doses per week [6]. Thus, PrEP is highly effective at reducing HIV risk for GBM with proper adherence.

Awareness and uptake of PrEP is continually growing in the U.S., and one major reason is that PrEP provides a mechanism to reduce personal HIV-related risk even when condom use is not possible [7]. Sixty-eight percent of young GBM recruited from Atlanta, Chicago, New York City, and social media sites for a multisite randomized controlled trial had heard of PrEP, and nearly 9% reported prior PrEP use [8]. PrEP awareness among men considered at high-risk of HIV grew from 13 to 86% between 2012 and 2015, and awareness improved even among lower-risk GBM from 29 to 58% over the same time period [9]. PrEP uptake among high-risk GBM increased from 5 to 31% between 2012 and 2015 in Washington state [9], and a continued increase in PrEP uptake among GBM is expected after long-acting injectable PrEP is introduced to the market [10]. Increases in awareness have resulted in higher uptake of PrEP in some but not all studies [9, 11], suggesting further behavioral research and interventions are needed to understand and facilitate potential movement along the PrEP cascade closer to uptake [12, 13].

Our previous research on individual-level uptake of PrEP has identified critical drop-offs in the earliest stages of the Motivational PrEP Cascade for GBM [13, 14]. Most notably, only 9.1% of men objectively identified by CDC criteria [15] as candidates for PrEP were currently on PrEP, and the largest drop-offs occurred in the earliest stages of willing (i.e., PrEP pre-contemplation) and intending to initiate PrEP for oneself (i.e., one component of PrEParation) [13]. Higher intentions for PrEP use for oneself were associated with higher pressure from their partners to discontinue condom use [14], highlighting the powerful influence of the social control partners exert over one another in relationships. This paper extends this prior research to look at unique correlates of partner PrEP importance and willingness to try to convince their partner to initiate PrEP specifically with men in main partnerships in this cohort sample. Given our prior findings about self-PrEP use, we aim to control for individual perceptions of PrEP use when testing correlates of potential partner PrEP use outcomes. Uniquely, we are then able to distinguish potential priority between individual- and dyadic-level interventions to increase PrEP uptake among GBM.

Given the salience of main partnerships as a context for HIV transmission [2, 3], it is critical to understand factors that might influence PrEP uptake among partnered GBM specifically. Unlike their single counterparts, sexual health for GBM in relationships is inherently linked to their partners'. Sexual health goals are reconciled by drawing on the resources of both members of the couple [16]. In what has been termed “a transformation process” [17], HIV prevention transforms from an individual to collective behavior with implications for both partners of a relationship. Main partners exert a degree of social control over one another's health behavior in ways that directly influence HIV-related risk. Research conducted within the context of Couples Interdependence Theory [17] has demonstrated that GBM in same-sex relationships utilize a range of health-related social control strategies with the goal of enhancing their partners' health-promotion behaviors and discouraging health-risk behaviors [18]. While these efforts often encompass health beyond HIV, HIV-related behaviors were identified among those most frequently targeted by partners' health-related control efforts [18].

Incorporating attention to the manner in which partners shape one another's HIV-related health behavior and risk opens new avenues for prevention messaging. As with all sexual partnerships, the interconnected HIV risk that GBM have with their partners [2, 3] makes prevention at the dyadic-level as important as the individual-level when prioritizing population-level HIV prevention. Conceptualizing interdependency theory into HIV prevention offers a promising avenue to leverage partner influence on PrEP uptake for one or both members of the couple; however, doing so requires an understanding of which GBM are most open to encouraging PrEP uptake in their partners. Therefore, we sought to explore how partnered GBM could reduce their interconnected HIV risk through potential partner PrEP uptake (i.e., PrEP-related social control), testing the influence of sexual arrangements and other known correlates of HIV risk with interpersonal implications including sexual behavior, intimate partner violence victimization, and alcohol and drug use. While social control often includes targeted strategies for developing behavioral changes [17], we sought to study the initial impressions of partnered GBM on potential partner PrEP uptake. In this sense, we aim to study the openness to PrEP-related social control – or the “given situation” that leads into the transformation process of behavior change based on relationship motives, among other things in interdependency theory [17] – that may facilitate future research into developed strategies for individuals to influence potential partner PrEP uptake.

Research on same-sex male couples has consistently shown that GBM regularly form sexual arrangements – understandings about the boundaries and limitations on sexual activities with partners outside the relationship [19, 20]. One motivation for these arrangements is to manage HIV-related risk [21, 22]. Existing research suggests that the relevance of sexual arrangements extends to partners' communication around PrEP. While some GBM were comfortable discussing PrEP with their main partner, GBM in monogamous relationships worried their main partner would suspect they had broken their sexual agreement if PrEP discussions were initiated [23]. PrEP was seen as more appealing if it was conceptualized as a couple's activity (rather than an individual health behavior), where partner PrEP use was perceived to offer a level of social support for their personal PrEP use, particularly among GBM in seroconcordant open relationships [23].

The relevance of sexual arrangements is further reflected in CDC guidance for PrEP dissemination [15]. These guidelines specifically designate partnered GBM in non-monogamous or serodiscordant partnerships as high priority. In contrast, those who are in HIV-negative seroconcordant relationships with monogamous arrangements as a lower priority group for PrEP dissemination. Research on risk perceptions among partnered GBM indicates that personal perceptions of HIV risk mirror these guidelines. GBM in monogamous relationships are less likely to get tested for HIV [24, 25] and estimate their HIV-related risk to be lower than those in non-monogamous relationships [25]. Nonetheless, research is rather limited on the potential initiation of PrEP into established relationships, suggesting additional need to study the potential “openness to HIV prevention” which we measure as prior history of condom use within relationships.

Further exploration of potential partner PrEP use is also needed accounting for additional relationship arrangements beyond monogamous and open. While a substantial amount of this existing research has distinguished between monogamous and non-monogamous arrangements [e.g., 19, 26], a growing body of literature has identified meaningful subtypes of non-monogamy among GBM. This latter work has distinguished between open arrangements – in which primary partners may have sex with people outside the relationship independently – and monogamish arrangements – in which sex with casual or outside partners is restricted to situations in which both partners in the primary relationship are present [20, 22].

Relative to condom use, which must be implemented in the moment as sex is occurring, PrEP use could potentially provide HIV protection to individuals in situations where interpersonal barriers to condom use are evident. For example, intentions to use PrEP were higher among men who viewed condom use as a barrier to intimacy or emotional closeness [14, 27]. Intimate partner violence (IPV) represents a context which may be characterized by extreme interpersonal barriers to personal HIV prevention, and the experience of IPV has been associated with lower self-efficacy to negotiate condom use [28]. PrEP use has resulted in a feeling of agency among GBM [7, 23, 29], where individuals can protect themselves against HIV without relying solely on condom use. At the same time, a history of IPV victimization may also substantially inhibit the exertion of health-related social control on one's partner. IPV is associated with dyadic inequalities [30], which may also make it less likely that a victimized partner would then attempt to influence his partner's HIV-related health behavior. Because PrEP can protect individuals against HIV when condoms are not used, PrEP has major implications for HIV protection even in forced sexual interactions.

Drug use is a well-established predictor of HIV-related risk among GBM [31-33] and is another important factor to consider in the study of potential partner PrEP uptake. The disinhibiting effects of drug and alcohol use on HIV prevention behaviors (e.g., condom use) [34, 35] make substance users ideal candidates for individual PrEP use, yet nearly 40% of drug-using GBM had concerns that their substance use would affect their ability to maintain optimal PrEP adherence in prior research [36]. Partner PrEP uptake could help GBM who use drugs reduce their risk for HIV through their partners, particularly if they perceive their substance use patterns affecting their own ability to use PrEP optimally. The use of drugs has been clearly linked to sexual arrangements among partnered GBM; monogamous men are less likely to report drug use than their non-monogamous counterparts and partners' drug use is more similar to one another among those in monogamous arrangements [33]. Partner PrEP uptake could assist substance-using men in non-monogamous relationships the most in reducing their HIV risk. In previous qualitative research with this population, men reported the desire for partner PrEP use because of the added support it would offer them in taking PrEP and added protection afforded against HIV based on their partners' sexual behavior [23]. While plausible, no studies have examined the relative utility of drug use and sexual arrangements as competing correlates of PrEP-related social control.

The purpose of the current study was to explore factors that might indicate elements of PrEP-related social control among partnered GBM. We use two items to measure important outcomes related to influencing PrEP-related social control for GBM. The first measure – the belief that going on PrEP may be an important HIV prevention strategy – is an integral component because GBM who do not find PrEP important are unlikely to try to persuade their partner to initiate its use. Our second outcome measure assessed willingness to persuade one's partner to go on PrEP, which is our primary outcome of interest to facilitate this stepwise progression toward partner PrEP uptake. Analyses examined the demographic, relationship arrangement, behavioral characteristics, and IPV victimization as correlates of these two outcomes in a U.S. nationally representative sample of GBM. We hypothesized men in open and monogamish relationship arrangements would perceive PrEP as more important for their partners and would be more willing to convince their partner to use PrEP because of higher-HIV risk perceptions. We hypothesized men with more openness to HIV prevention – measured as prior history of condom use within the relationship – to respond more favorably to partner PrEP outcomes while controlling for current condom use. Nonetheless, we acknowledge the relatively exploratory nature of including prior and current condom use in our models. Given prior research with drug users, we hypothesized that substance users would find PrEP more important for their partner and would be more willing to talk to their partner about PrEP initiation. We hypothesized IPV victimization to be negatively associated with willingness to persuade one's partner to use PrEP (but not with perceived importance of PrEP for one's partner), as men who have experienced IPV have reported less confidence in their ability to negotiate HIV prevention activities. Finally, we hypothesized participants' own PrEP willingness and intentions to be positively associated with partner PrEP importance and their willingness to convince their partner to use PrEP. Those with higher perceptions of PrEP for themselves might find it similarly important for their partner, underscoring the importance of partner protection beliefs.

Methods

Data for this study were taken from the One Thousand Strong study [37], a national cohort of 1,071 GBM in the U.S. Briefly, One Thousand Strong is a study of HIV-negative GBM prospectively followed for three years. A targeted sampling strategy was used to ensure adequate representation with census data for same-sex households based on age, race/ethnicity, and U.S. geography. All men enrolled at baseline had a confirmed HIV-negative test result. Cross-sectional data from the 12-month follow-up were used for this analysis. During this assessment, partnered men were asked about the importance of partner PrEP use and their willingness to persuade their partner to use PrEP. Recruitment and enrollment details have been detailed elsewhere [10, 13, 14, 37, 38]. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of CUNY.

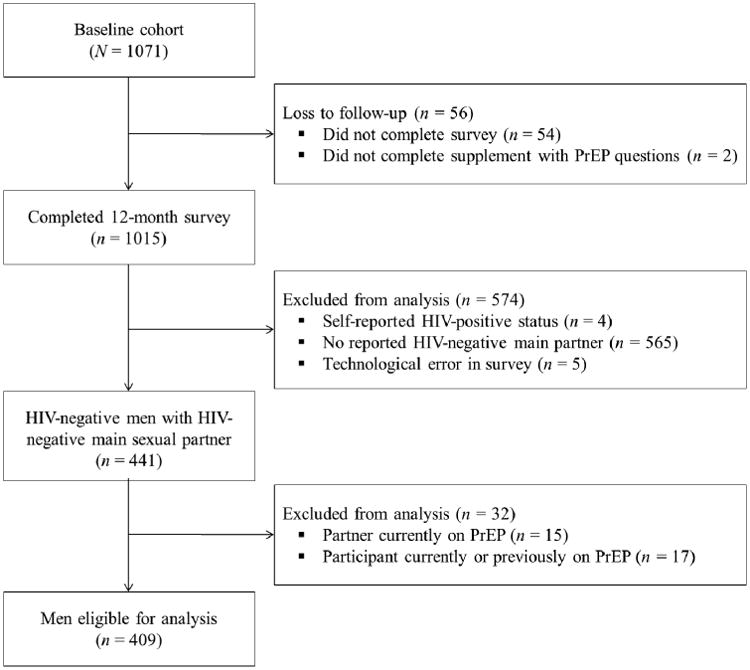

Of the 1,071 GBM enrolled at baseline, 1,015 (94.8%) completed the 12-month follow-up survey. To be considered for this analysis, men had to self-report HIV-negative and be in a main partnership with an HIV-negative or unknown status main partner (n = 441) at the time of the 12-month assessment. We excluded men with main partners already on PrEP (n = 15) and those participants who themselves were currently or previously on PrEP (n = 17). Of note, this excluded 9 participants who reported concurrent PrEP use with their partner at the time of the survey. This resulted in a final analytic sample of 409 HIV-negative, PrEP-naïve men with HIV-negative or unknown status main partners who were also PrEP-naïve (see Figure 1 for eligibility flow diagram).

Figure 1.

Eligibility flow diagram

Measures

Demographics

Participants provided demographic data, including age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, employment status, income, and their geographic region of residence determined from postal codes.

Relationship characteristics

Men were asked about their relationship arrangement with their main sexual partner. Men were coded as being monogamous if they responded, “neither of us has sex with others, we are monogamous” or “I don't have sex with others, but I don't know about my partner.” Men who reported an exclusive play-together arrangement (“both of us have sex with others together”), where only outside partners are allowed if they have sex with them together, were coded as in a monogamish relationship arrangement; this included men who reported a monogamous arrangement but reported sex together with an outside partner in the past 3 months [22, 33, 39]. Finally, men were coded as in an open arrangement if they reported allowing outside sexual partners in any form other than an exclusive play-together arrangement (“only I have sex with others;” “only my partner has sex with others;” “both of us have sex with others separately;” “we both have sex with others together and separately;” “I have sex with others, but I don't know about my partner”). Some men in monogamous relationship arrangements reported having casual sex partners; therefore we included a separate dichotomous variable measuring any casual partners in the past 3 months (regardless of relationship arrangement). Relationship duration in years was calculated using the month and year of the relationship's start as reported by the participant. Participants were asked whether they currently used condoms with their main partner as a dichotomous indicator, and we similarly assessed whether they had ever used condoms with their current main partner as a proxy for “openness to HIV prevention.”

Substance use

Men were asked about prior drug use in the past 12 months, including cocaine, crystal meth, ecstasy, GHB/GBL, heroin/opiates, ketamine, and crack. We then created a dichotomous indicator of any drug use in the past year, excluding marijuana as we assessed marijuana separately. We assessed for hazardous drinking patterns in the past 12 months using the AUDIT-C, a 3-item questionnaire used to identify hazardous alcohol use with good reliability, sensitivity, and specificity in prior research [40]. Men were considered to engage in hazardous drinking if they reported an AUDIT-C score of 4 points or higher (α = .69; scale range: 0-12), the recommended threshold to identify hazardous alcohol use in men [40]. Marijuana dependence was measured using the DAST-10 questionnaire for marijuana use, a 10-item questionnaire about life complications associated with marijuana use [41]. Marijuana dependence was coded if men scored 4 or higher on the DAST-10 for marijuana (α = .66; scale range: 0-10), and men who did not report any marijuana use were coded as non-dependent. This scale has demonstrated good sensitivity and specificity when compared with the structured clinical interview for DSM-IIIR in prior research [42].

Intimate partner violence victimization

Participants were asked a series of questions about victimization of IPV [43, 44]. Men were asked if they had experienced each of 12 forms of IPV measuring psychological/symbolic, physical, and sexual abuses in the past 12 months. We then coded men as having experienced any form of IPV if they selected one or more forms of IPV victimization.

PrEP willingness and intentions for oneself

Perceptions of PrEP use for themselves – the participant – were measured using two questions [10, 13, 14]: 1) PrEP willingness, and 2) PrEP intentions. PrEP willingness was measured by a single question: “How likely would you be to take PrEP if it were available for free?” with responses ranging from 1 (I would definitely not try) to 5 (I would definitely try). PrEP intentions were also measured by a single question: “Do you plan to begin PrEP?” Response categories ranged from 1 (no, I definitely will not begin taking PrEP) to 5 (yes, I will definitely begin taking PrEP).

Perceptions of PrEP use for partners

Two outcomes were measured: 1) importance of partner PrEP, and 2) partner persuasion to use PrEP. Importance of partner PrEP was measured by a single question: “How important would it be for your partner to take PrEP?” with response options ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 4 (very important). Partner persuasion to use PrEP was also measured by a single question: “How likely would you be to try to convince him to consider starting PrEP?” Response options ranged from 1 (I would definitely not try) to 5 (I would definitely try).

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate associations with indications of PrEP-related social control outcomes were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc comparisons to compare means across categorical predictors and Pearson's correlation for continuous predictors on partner PrEP importance and partner persuasion to use PrEP. All post-hoc analyses were adjusted for multiple-comparison testing using Scheffe's method, as applicable. All variables were retained for inclusion in fully-adjusted regression models, which were conducted using ordinary least squares regression models calculated separately for perceived partner PrEP importance and willingness to persuade one's partner to use PrEP.

Results

Four-hundred nine HIV-negative, PrEP-naïve GBM with HIV-negative, PrEP-naïve main partners responded to questions about the importance of partner PrEP and their willingness to persuade their partner to start PrEP. Average respondent age was 41 years old (range: 19-80; see Table 1). The majority of men were White and identified as gay. Men had a relatively equal distribution of educational backgrounds; most men were employed full-time (76%), and more than half earned $50,000 or more per year. Of the 409 partnered men, more than half reported a monogamous relationship arrangement, 10% reported a monogamish arrangement, and 37% an open arrangement with their main partner. Average relationship duration was 9 years and 61% of men reported using a condom at least once with their main partner, with 11% reporting current condom use. Over a third of the participants reported having casual sex partners. A small number of men reported drug use in the past 12 months (7%) and marijuana dependence (2%), but roughly half of the men reported hazardous drinking patterns in the past year. Recent IPV victimization was reported by more than 19% of these GBM.

Table 1. Demographics, relationship characteristics, substance use, and intimate partner violence victimization and their bivariate associations with the importance of partner PrEP and partner persuasion to use PrEP (n = 409).

| Importance of Partner PrEP Use | Partner Persuasion to use PrEP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical Predictors | n | % | M | SD | M | SD |

| Race/Ethnicity | F(3, 405) = 3.4*† | F(3, 405) = 1.6 | ||||

| Black | 25 | 6.1 | 2.1a | 1.0 | 2.6 | 1.2 |

| Latino | 57 | 13.9 | 2.1a | 0.9 | 2.6 | 1.2 |

| White | 301 | 73.6 | 1.8a | 0.9 | 2.3 | 1.2 |

| Other/Multiracial | 26 | 6.4 | 2.1a | 0.9 | 2.5 | 1.3 |

| Education | F(2, 406) = 1.9 | F(2, 406) = 5.4** | ||||

| Less than Bachelor's degree | 153 | 37.4 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.6a | 1.3 |

| Bachelor's degree | 138 | 33.7 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 2.3b | 1.2 |

| More than Bachelor's degree | 118 | 28.9 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 2.2b | 1.0 |

| Employment | F(2, 406) = 1.1 | F(2, 406) = 0.8 | ||||

| Unemployed | 45 | 11.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 1.3 |

| Part-time employment | 53 | 13.0 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 1.3 |

| Full-time employment | 311 | 76.0 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.2 |

| Income | F(2, 406) = 1.0 | F(2, 406) = 1.9 | ||||

| Less than $20k per year | 48 | 11.7 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 1.3 |

| $20k to $49k per year | 148 | 36.2 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 1.3 |

| $50k or more per year | 213 | 52.1 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 1.1 |

| Geographic Region | F(3, 405) = 3.1*†† | F(3, 405) = 3.5*†† | ||||

| Northeast | 78 | 19.1 | 1.8ab | 0.9 | 2.3ab | 1.1 |

| Midwest | 76 | 18.6 | 1.7a | 0.8 | 2.1a | 1.2 |

| South | 160 | 39.1 | 2.0b | 0.9 | 2.6b | 1.3 |

| West | 95 | 23.2 | 1.8ab | 0.9 | 2.3ab | 1.2 |

| Relationship Arrangement with Main Partner | F(2, 406) =19.8*** | F(2, 406) = 20.8*** | ||||

| Monogamous | 217 | 53.1 | 1.6a | 0.8 | 2.0 a | 1.1 |

| Monogamish | 42 | 10.3 | 2.2b | 0.9 | 3.0b | 1.3 |

| Open | 150 | 36.7 | 2.2b | 0.9 | 2.7b | 1.2 |

| Any Casual Sex Partners | F(1, 407) =32.4*** | F(1, 407) = 26.9*** | ||||

| No | 268 | 65.5 | 1.7a | 0.8 | 2.2a | 1.1 |

| Yes | 141 | 34.5 | 2.2b | 0.9 | 2.8b | 1.2 |

| Current Condom Use with Main Partner | F(1, 407) = 0.0 | F(1, 407) = 0.6 | ||||

| No | 365 | 89.2 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.2 |

| Yes | 44 | 10.8 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 1.1 |

| Ever Condom Use with Main Partner | F(1, 407) = 2.3 | F(1, 407) = 3.7 | ||||

| No | 161 | 39.4 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 1.4 |

| Yes | 248 | 60.6 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 1.1 |

| Any Drug Use (Past 12-Months) | F(1, 407) =11.9*** | F(1, 407) = 18.4*** | ||||

| No | 382 | 93.4 | 1.8a | 0.9 | 2.3a | 1.2 |

| Yes | 27 | 6.6 | 2.4b | 1.0 | 3.3b | 1.5 |

| Hazardous Drinking (Past 12-Months)1 | F(1, 407) = 2.0 | F(1, 407) = 2.1 | ||||

| No | 212 | 51.8 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 1.2 |

| Yes | 197 | 48.2 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| Marijuana Dependent (Past 12-Months)2 | F(1, 407) = 1.5 | F(1, 407) = 5.3* | ||||

| No | 402 | 98.3 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.4a | 1.2 |

| Yes | 7 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 3.4b | 1.6 |

| Any IPV Experienced (Past 12-Months) | F(1, 407) = 9.3** | F(1, 407) = 14.7*** | ||||

| No | 330 | 80.7 | 1.8a | 0.9 | 2.3a | 1.2 |

| Yes | 79 | 19.3 | 2.2b | 1.0 | 2.8b | 1.3 |

| Continuous Predictors | M | SD | Pearso n's r | Pears on's r | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age | 40.8 | 13.7 | -0. 1 | -0. 1** | ||

| Relationship Duration with Main Partner in Years | 9.0 | 9.1 | -0. 1 | -0 .1* | ||

| PrEP Willingness for Oneself (Range: 1-5) | 3.3 | 1.3 | 0.5*** | 0.6*** | ||

| PrEP Intentions for Oneself (Range: 1-5) | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.5*** | 0.6*** | ||

Notes:

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.001;

determined by AUDIT-C with threshold ≥ 4 (scale range: 0-12; Reinart & Allen, 2007);

determined by DAST-10 for marijuana with threshold ≥ 4 (scale range: 0-10; Bohn, Barbor, & Kranzler, 1992);

means in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) in pairwise comparisons, but complex comparisons are described as a note. Percentages may not add up to 100 because of rounding. All post-hoc comparisons were adjusted for multiple-comparison testing by Scheffe's method.

White is significantly different than all other race/ethnicity combined (p ≤ 0.01), but not separately.

South is significantly different than all three regions combined (p ≤ 0.01).

Importance of Partner PrEP Use

Men found partner PrEP moderately important (M = 1.9, SD = 0.9, range: 1-4). In bivariate analyses (see Table 1 for complete results), White GBM found partner PrEP use less important than all other racial groups combined. Moreover, men in the South thought PrEP was more important for their partners compared to all other U.S. geographical regions combined. While men in monogamish and open relationship arrangements did not differ in perceptions of partner PrEP importance, men in monogamous arrangements found PrEP significantly less important for their partner compared to other arrangements. Having a casual sex partner, compared to not, was also significantly associated with higher partner PrEP importance, as was any recent drug use compared to not. Men who recently experienced any form of IPV victimization thought partner PrEP use was significantly more important than men who had not experienced IPV. Lastly, higher PrEP willingness and intentions were significantly associated with higher partner PrEP use importance.

In the first regression model – excluding self-willingness and self-intentions around PrEP (see Model 1a, Table 2), Latino men found partner PrEP significantly more important than White men, and men from the Midwest found partner PrEP less important than men from the South. Men in monogamish and open relationship arrangements with their main partners thought partner PrEP use was significantly more important than men in monogamous relationships. Having a casual sex partner was associated with significantly higher partner PrEP use importance, but any prior use of condoms with their main partner was associated with less importance of partner PrEP. Prior IPV victimization was associated with significantly higher partner PrEP importance.

Table 2. Results of fully-adjusted linear regression models predicting the importance of partner PrEP use and partner persuasion to use PrEP (n = 409).

| Importance of Partner PrEP Useb | Partner Persuasion to Use PrEPb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 1b | Model 2b | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | |

| Age | -0.00 (0.00) | -0.02 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.08 | -0.00 (0.01) | -0.05 | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.06 |

| Race/Ethnicity (Ref: White) | ||||||||

| Black | 0.15 (0.18) | 0.04 | 0.01 (0.16) | 0.00 | 0.05 (0.24) | 0.01 | -0.17 (0.19) | -0.03 |

| Latino | 0.26 (0.13)* | 0.10 | 0.18 (0.11) | 0.07 | 0.13 (0.17) | 0.04 | -0.01 (0.14) | -0.00 |

| Other/Multiracial | 0.28 (0.17) | 0.08 | 0.19 (0.16) | 0.05 | 0.16 (0.23) | 0.03 | -0.00 (0.19) | -0.00 |

| Education (Ref: Less than Bachelor's degree) | ||||||||

| Bachelor's degree | -0.10 (0.10) | -0.05 | 0.00 (0.09) | 0.00 | -0.33 (0.13)* | -0.13 | -0.16 (0.11) | -0.06 |

| More than Bachelor's degree | -0.17 (0.11) | -0.09 | -0.10 (0.10) | -0.05 | -0.35 (0.15)* | -0.13 | -0.23 (0.12)* | -0.09 |

| Employment (Ref: Unemployed) | ||||||||

| Part-time employment | -0.26 (0.17) | -0.10 | -0.16 (0.15) | -0.06 | -0.30 (0.23) | -0.08 | -0.13 (0.19) | -0.04 |

| Full-time employment | -0.09 (0.15) | -0.04 | -0.08 (0.13) | -0.04 | -0.04 (0.20) | -0.01 | -0.03 (0.16) | -0.01 |

| Income (Ref: Less than $20k per year) | ||||||||

| $20k to $49k per year | -0.14 (0.15) | -0.07 | -0.02 (0.14) | -0.01 | -0.09 (0.20) | -0.03 | 0.11 (0.16) | 0.04 |

| $50k or more per year | -0.12 (0.16) | -0.07 | -0.03 (0.14) | -0.02 | -0.13 (0.22) | -0.05 | 0.02 (0.17) | 0.01 |

| Geographic Region (Ref: South) | ||||||||

| Northeast | -0.14 (0.12) | -0.06 | -0.01 (0.10) | -0.00 | -0.26 (0.15) | -0.08 | -0.03 (0.13) | -0.01 |

| Midwest | -0.31 (0.12)** | -0.14 | -0.14 (0.11) | -0.06 | -0.41 (0.16)** | -0.13 | -0.13 (0.13) | -0.04 |

| West | -0.13 (0.11) | -0.06 | -0.06 (0.10) | -0.03 | -0.25 (0.14) | -0.09 | -0.13 (0.12) | -0.04 |

| Relationship Arrangement with MPa (Ref: Monogamous) | ||||||||

| Monogamish | 0.43 (0.15)** | 0.15 | 0.19 (0.14) | 0.07 | 0.80 (0.20)*** | 0.20 | 0.40 (0.16)* | 0.10 |

| Open | 0.34 (0.13)** | 0.18 | 0.12 (0.11) | 0.06 | 0.52 (0.17)** | 0.21 | 0.15 (0.14) | 0.06 |

| Relationship Duration with MP in Years | -0.01 (0.01) | -0.08 | -0.00 (0.01) | -0.05 | -0.01 (0.01) | -0.11 | -0.01 (0.01) | -0.08 |

| Any Casual Sex Partners (Ref: No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.26 (0.12)* | 0.14 | 0.09 (0.11) | 0.05 | 0.25 (0.16) | 0.10 | -0.05 (0.13) | -0.02 |

| Current Condom Use with MP (Ref: No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.05 (0.14) | 0.02 | 0.02 (0.12) | 0.01 | -0.00 (0.19) | -0.00 | -0.06 (0.15) | -0.01 |

| Ever Condom Use with MP (Ref: No) | ||||||||

| Yes | -0.18 (0.09)* | -0.10 | -0.05 (0.08) | -0.03 | -0.25 (0.12)* | -0.10 | -0.03 (0.10) | -0.01 |

| Any Drug Use (Past 12-Months; Ref: No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.31 (0.18) | 0.09 | 0.15 (0.16) | 0.04 | 0.50 (0.23)* | 0.10 | 0.23 (0.19) | 0.05 |

| Hazardous Drinking (Past 12-Months; Ref: No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.08 (0.08) | 0.05 | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.00 | 0.10 (0.11) | 0.04 | -0.02 (0.09) | -0.01 |

| Marijuana Dependent (Past 12-Months; Ref: No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.05 (0.33) | 0.01 | 0.02 (0.29) | 0.00 | 0.47 (0.44) | 0.05 | 0.40 (0.35) | 0.04 |

| Any IPV Experienced (Past 12-Months; Ref: No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.22 (0.11)* | 0.10 | 0.13 (0.09) | 0.06 | 0.41 (0.14)** | 0.13 | 0.27 (0.11)* | 0.09 |

| PrEP Willingness | -- | -- | 0.18 (0.04)*** | 0.28 | -- | -- | 0.27 (0.05)*** | 0.30 |

| PrEP Intentions | -- | -- | 0.25 (0.05)*** | 0.28 | -- | -- | 0.46 (0.06)*** | 0.39 |

|

| ||||||||

| Model Statistics | ||||||||

| F-test (df) | 4.2 (23, 385)*** | 9.3 (25, 383)*** | 5.3 (23, 385)*** | 16.3 (25, 383)*** | ||||

| Adj-R2 | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.48 | ||||

Notes:

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.001;

MP = main partner;

Model 1a and Model 2a are the adjusted regression models – excluding PrEP willingness and intentions, whereas Model 1b and Model 2b further adjust for self-willingness and self-intentions around PrEP.

When adjusted for self-PrEP use willingness and intentions (see Model 2a, Table 2), all of the aforementioned associations became non-significant. Higher PrEP willingness and intentions were the largest contributors in the model predicting higher partner PrEP use importance, as evident by moderately large standardized beta coefficients (β = 0.28, p ≤ 0.001, for both associations).

Partner Persuasion to Use PrEP

Partner persuasion to use PrEP was modest in this sample (M = 2.4, SD = 1.2, range: 1-5). In bivariate analyses (see Table 1 for complete results), older men and men who had a Bachelor's degree or higher were significantly less willing to try to convince their partner to use PrEP (referred to as partner persuasion to use PrEP hereafter). Men in the South had significantly higher partner persuasion to use PrEP than all other U.S. regions. Men in monogamous relationships had significantly lower partner persuasion to use PrEP, but no differences were observed between men in monogamish and open arrangements. Longer relationship duration with the main partner was negatively associated with partner persuasion to use PrEP; men in longer relationships were less willing to initiate partner PrEP discussions. Having a casual sex partner was associated with higher partner persuasion to use PrEP, but no effects were observed by condom use indicators on partner persuasion to use PrEP. Drug users had higher partner persuasion to use PrEP, but hazardous drinking and marijuana dependency had no effect on partner persuasion to use PrEP. Men with a history of IPV victimization had higher partner persuasion to use PrEP compared to those who had not experienced IPV victimization. Similar to partner PrEP importance, partner persuasion to use PrEP was significantly associated with self-willingness and intentions to use PrEP.

In the adjusted regression model predicting partner persuasion to use PrEP – excluding self-willingness and self-intentions regarding PrEP (see Model 1b, Table 2), men with higher educational attainment had significantly lower partner persuasion to use PrEP than those with less than a Bachelor's degree. Men from the Midwest had lower scores on the partner persuasion to use PrEP question than men from the South, but no other geographical differences were found. Men in monogamish and open relationship arrangements had significantly higher partner persuasion to use PrEP than men in a monogamous agreement, and prior condom use with their partner was associated with lower partner persuasion to use PrEP. Men who experienced IPV victimization had higher partner persuasion to use PrEP compared to those who had, and drug use in the past year was associated with significantly higher partner persuasion to use PrEP.

After adjusting for the participants' willingness and intentions to use PrEP (see Model 2b, Table 2), higher educational attainment and IPV remained significant predictors. PrEP willingness and intentions were both significantly associated with partner persuasion to use PrEP with large standardized coefficients (β = 0.3, p ≤ 0.001; β = 0.4, p ≤ 0.001; respectively). Attainment of an educational degree higher than a Bachelor's degree was associated with lower partner persuasion to use PrEP than men with less than a Bachelor's degree. Compared to men in a monogamous arrangement, men in monogamish relationships had higher partner persuasion to use PrEP. No difference between men in open and monogamous relationships was observed after adjusting for the participants' willingness and intentions to use PrEP. Experiencing any IPV in the past 12 months was still significantly associated with higher partner persuasion to use PrEP in Model 2b. The explanation of variance was good in all models, and the adjusted Model 2b of partner persuasion to use PrEP including self-willingness and self-intentions explained 48% of the variance after adjustment for the number of variables added into the model.

Discussion

This study centered on the potential of PrEP-related social control for HIV-negative partnered GBM, but findings from our study suggest the largest predictors of partner PrEP use outcomes measured were the willingness and intentions of GBM to use PrEP personally. Based on the observed strong effects of self-PrEP willingness and intentions on partner PrEP use importance and persuasion, we suggest individual-level interventions should be prioritized for GBM at higher-HIV risk. Interventions targeting individuals may have a large spillover effect into couples, even without intervening on partners. Nonetheless, we found sexual arrangements, IPV, and drug use were also important factors in the willingness of GBM to talk to their partner about PrEP, suggesting individual interventions – albeit substantially more feasible and cost-effective – would be limited if they did not account for relationship factors including the couple's relationship arrangement, condom use history, patient's history of IPV victimization, and current drug use patterns. PrEP use has also been considered more appealing for partnered GBM when conceptualized as a couple's activity [23]. Thus, we suggest the need for both individual and dyadic-level interventions to more fully support PrEP uptake among partnered GBM, especially when we consider the importance of both uptake and adherence.

Findings related to sexual arrangements and PrEP-related social control (both perceived importance of PrEP for one's partner and willingness to persuade a partner to use PrEP) conformed to hypotheses. This finding is consistent with research indicating that monogamous men perceive themselves at lower risk of HIV infection [25]. Broadly, these results support previous work that monogamous men were hesitant to communicate about PrEP out of concern that broaching the topic of HIV prevention would cause a partner to suspect that their sexual agreement had been violated in some way [23]. For many GBM in monogamous relationships, their perceptions of lower HIV risk are accurate. However, dyadic-level interventions could help improve communication about sexual behaviors and HIV prevention among those couples whose perceived relationship arrangement is different from their sexual behaviors collectively as a couple. Because some men in monogamous relationship arrangements reported having casual sex partners in this sample (presumably in violation of their sexual arrangement), interventions with partners together using a third-party counselor could potentially help couples accurately assess their HIV risk.

Even after accounting for variability in sexual arrangements, men who reported sex with outside partners viewed a partner's use of PrEP as more important compared to those who had no casual partners. However, sexual behavior with casual partners did not contribute to the prediction of willingness to persuade a partner to use PrEP above and beyond sexual arrangement. This pattern would suggest that while sexual behavior with casual partners may shape the perception of partner PrEP use importance among GBM regardless of sexual arrangement, sexual arrangements are a much stronger factor than actual behavior in determining willingness to communicate about PrEP.

These findings have implications for HIV prevention with partnered GBM, and our findings highlight the challenges faced particularly by monogamous GBM in discussing PrEP with their partners. While many of these couples may be at relatively low-HIV risk, findings suggest GBM in monogamous relationships may experience barriers to discussing PrEP even in instances where they perceive the potential importance of PrEP. Dyadic interventions – such as Couples HIV Testing and Counseling (CHTC) [45] – may provide a context to effectively elicit PrEP discussions because CHTC involves facilitating a discussion about the couple's sexual agreement and responses to potential arrangement violations. These findings suggest that providers of CHTC should introduce the topic of PrEP even for monogamous couples. The introduction of the topic by a neutral third party (i.e., the CHTC facilitator) may reduce some of the interpersonal barriers to PrEP discussion and offer an opportunity for men who believe PrEP could be useful to express this to their partners.

Only men in monogamish relationship arrangements had higher partner persuasion to use PrEP after adjusting for perceptions of self-willingness and intentions to use PrEP. This finding mirrors previous research, which indicated that men in monogamish relationships are more likely to engage in HIV prevention (i.e., condom use) with casual partners compared to those in open relationships [22]. Men in monogamish arrangements may have higher partner protection beliefs compared to men in open relationships, despite similar perceptions of partner PrEP importance. Men in open relationships might believe their partners are responsible for their own health given their (and/or their partner's) autonomy in sexual behaviors; yet partner PrEP uptake could be considered an individual protection belief – thus why they find it important, understanding the HIV risk associated with their partner's behaviors – but may be unwilling to try to convince their partner to initiate PrEP because of less perceived responsibility to protect their partner's health. Further research is needed exploring individual and partner protection beliefs between the various relationship arrangements to more fully understand this phenomenon.

Findings related to IPV were counter to hypothesized associations. IPV victimization was associated with higher partner PrEP importance, and experiencing IPV was a significant factor associated with higher partner persuasion to use PrEP, even after adjusting for self-PrEP use perceptions. IPV victimization has commonly been associated with less engagement in HIV prevention activities such as condom use [46, 47] and higher HIV incidence [48]. These results suggest it is possible that IPV may interact very differently with indications of PrEP-related social control relative to other HIV prevention methods. The experience of IPV victimization could trigger components of the interdependency theory that lead to greater consideration of partner PrEP. Specifically, IPV experiences could trigger greater cognition and emotion related to their own needs and motives and connects them to their partners' potential needs. These components are based on initial reactions and part of the decision-making process for transformational behavioral change [17] – in this case, attempting to convince a partner to initiate PrEP. IPV might also diminish one's sense of joint or shared control and leave the victim with the perception that sexual health is actually an individual-level matter. Perceptions of PrEP for both self and partner could increase precisely because the individual believes they are not responsible for each other's HIV prevention. Alternatively, these findings may arise from circumstances in which IPV from another relationship then shapes PrEP-related social control in the current relationship with the main partner. Our measure of IPV victimization examined occurrences of IPV in the past year and did not specify whether the perpetrator was a current or former partner, or whether the perpetrator was a main or casual partner. Others have noted that PrEP uptake is associated with an enhancement in self-efficacy [7, 23, 29]. It may be that for men who experienced IPV in a different relationship, partner PrEP use is viewed as affording HIV protection even from unforeseen HIV risk events.

The influence of drug use remained a significant correlate of partner PrEP outcomes, even after adjusting for relationship factors. Men who engaged in drug use were more willing to try to convince their partner to use PrEP despite no significant differences in importance as compared to non-drug users. This effect became non-significant after adjusting for self-willingness and intentions for PrEP use. This pattern suggests personal perceptions of PrEP might be a better predictor of their potential PrEP-related social control than drug use per se. Interestingly, we found no difference in self-willingness and intentions to use PrEP at baseline within our full sample of GBM by drug use [14], but we found drug users within this sample of only partnered GBM more willing to talk to their partner about PrEP. These patterns support a hypothesis that relationship status may moderate the association between drug use and PrEP-related social control. Thus, partnered men may engage in drug use differently, and this finding could suggest higher engagement in biomedical HIV prevention.

To underscore PrEP as only one strategy to reduce HIV risk among GBM, we assessed for differences in outcomes based on condom use with their main partners using two measures. While we found no difference in partner PrEP outcomes based on current condom use, we found men who reported prior condom use with their main partner thought PrEP was significantly less important for their partner and were significantly less willing to try to convince their partner to initiate PrEP. One plausible explanation is that PrEP use may be subject to interpersonal barriers in a manner similar to condom use. Intimacy motivations were found to be a reason for condom use cessation among GBM with main sexual partners in prior research [49]. While some have found that partnered GBM who perceive condoms as a barrier to intimacy or emotional closeness had more positive views of PrEP [27], it is simultaneously possible that perceptions of PrEP could be similar – PrEP may disrupt intimacy among partnered GBM. PrEP use could be a reminder about lack of mutual monogamy, thus disrupting the emotional closeness of men. A second possibility is that couples who have used condoms in the past view them as a satisfactory prevention option if a future need arose and therefore perceive less benefit from the addition of PrEP as a prevention alternative. Additional research is needed exploring the perceptions of partnered GBM on the relational implications of PrEP and how condom behavior and related beliefs covary with PrEP initiation and attitudes.

With regard to general demographics, our findings are consistent with our prior reports on PrEP willingness and intentions (for self-use of PrEP) within our cohort study [14]. GBM with higher education were less willing to try to convince their partner to use PrEP, and those with more than a Bachelor's degree were still significantly less willing after adjustment of their self-PrEP use perceptions. These results are consistent with our prior assessment of PrEP willingness and intentions for oneself, which found GBM with lower educational attainment were more interested in PrEP [14]. A plausible explanation for differences by educational attainment is that men with lower educational attainment are often more highly targeted by HIV prevention efforts and could perceive themselves at higher HIV risk, thus men with higher education might be less concerned about HIV prevention comparatively. Moreover, men with higher educational attainment may have more perceived agency for HIV prevention compared to those with lower education and are therefore less reliant on partner protection because of individual protection beliefs. GBM in the Midwest differed from those who live in the South on both partner PrEP outcomes. Midwestern men found partner PrEP significantly less important and were significantly less willing to try to convince their partner to initiate PrEP than those in the South. Differences between these two groups are likely based on HIV risk appraisal because incidence rates dramatically differ between these two geographical regions [1].

Public health campaigns aimed at enhancing personal, positive perceptions of PrEP may facilitate PrEP-related social control between partners. We found that the best intendent predictors of our partner PrEP outcomes were willingness and intentions to use PrEP personally. To this end, efforts to enhance the acceptability of PrEP within the GBM community more broadly may facilitate dyadic processes that enhance PrEP uptake among partnered men, thus facilitating movement along the PrEP cascade [12]. Main partners have a unique supportive role in PrEP initiation [23] and likely adherence, based on analogous research with serodiscordant couples [50]. Thus, further research exploring the role and potential for PrEP within main partnerships is warranted to better support intervention development among partnered men at higher-HIV risk.

Limitations

Several limitations of this research are worthy of mention, despite the many strengths of our research. First, GBM in this study were based on a U.S. nationally representative sample of GBM; however, we were unable to purposively sample subgroups of GBM at higher-HIV risk. Second, as all data were collected by self-report based on responses at 12-month follow-up, we cannot rule out multiple testing effects and potential for response bias. We took steps to reduce demand effects by using a self-administered, online survey, but PrEP was described as at least 90% effective, perhaps biasing true immediate perceptions of PrEP. Third, the previously validated scales to measure hazardous alcohol use and marijuana dependence had less than ideal reliability. Further research is needed to improve the internal consistency of these abbreviated measures among this sample. Forth, this study excluded men currently or previously on PrEP. While these men are important for potential partner PrEP research, and we hope future research is expanded in this area, we think PrEP-naïve men are distinctly different than those who have prior PrEP use experience. Fifth, only HIV-negative men were included in this analytical sample; HIV-positive men with HIV-negative main partners may have very different determinants of PrEP-related social control. Sixth, while our measure of condom use points to the utility of future studies focused in this area, we are unable to determine why or when couples stopped using condoms in this study. Lastly, we do not have data related to whether couples have discussed PrEP previously, so we cannot distinguish between couples who have tried talking about PrEP with their partner previously. It is plausible that some men have talked to their partner about PrEP previously and this influenced their responses.

Conclusion

In this study, GBM believed partner PrEP was only moderately important, and men had a modest amount of willingness to try to convince their partner to initiate PrEP use. Men who found partner PrEP more important were in non-monogmous relationships (i.e., monogamish and open relationship agreements), had casual sex partners, had not used condoms with their partner previously, and had recently experienced IPV victimization. Partner persuasion to use PrEP was similarly associated with relationship arrangement, ever condom use with their partner, and IPV victimization, but drug users and those with lower educational attainment also had higher partner persuasion to use PrEP. The effects of a monogamish relationship arrangement and IPV victimization, in particular, remained significant predictors of partner persuasion to use PrEP even after adjusting for self-PrEP use perceptions – the largest predictor of willingness to convince a partner to initiate PrEP. Further research is needed with GBM in main sexual partnerships to aid in intervention development within this at-HIV risk population. Increasing individual perceptions of PrEP – including efforts to increase movement of GBM along the PrEP cascade closer to uptake – will be important for both individual and partner PrEP uptake.

Acknowledgments

One Thousand Strong study was funded by a research grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA036466; Jeffrey T. Parsons & Christian Grov, MPIs). H. Jonathon Rendina was supported by a Career Development Award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01-DA039030; H. Jonathon Rendina, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the other members of the One Thousand Strong Study Team (Ana Ventuneac, Demetria Cain, Mark Pawson, Ruben Jimenez, Chloe Mirzayi, Brett Millar, Raymond Moody, and Thomas Whitfield) and other staff from the Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies and Training (Chris Hietikko, Andrew Cortopassi, Brian Salfas, Doug Keeler, Chris Murphy, Carlos Ponton, and Paula Bertone). We would also like to thank the staff at Community Marketing Inc. (David Paisley, Heather Torch, and Thomas Roth). Finally, we thank Jeffrey Schulden at NIDA, the anonymous reviewers of this manuscript, and all of our participants in the One Thousand Strong study.

Funding: Funding support was provided by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01-DA036466; PIs: Parsons & Grov). H. Jonathon Rendina was supported by a National Institute on Drug Abuse Career Development Award (K01-DA039030).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards: Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.CDC. HIV surveillance report, 2015. 2015 Feb;27 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodreau SM, Carnegie NB, Vittinghoff E, et al. What drives the US and Peruvian HIV epidemics in men who have sex with men (MSM)? PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, Sanchez TH. Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. AIDS. 2009;23(9):1153–62. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832baa34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.USFDA. FDA approves first medication to reduce HIV risk. [Accessed April 3, 2015];2012 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm311821.htm.

- 5.Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(10):1601–3. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal- and community-based sexual health services. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(1):75–84. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant RM, Koester KA. What people want from sex and preexposure prophylaxis. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(1):3–9. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strauss BB, Greene GJ, Phillips G, et al. Exploring patterns of awareness and use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1288–98. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1480-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hood JE, Buskin SE, Dombrowski JC, et al. Dramatic increase in preexposure prophylaxis use among MSM in Washington state. AIDS. 2016;30(3):515–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Whitfield TH, Grov C. Familiarity with and preferences for oral and long-acting injectable HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national sample of gay and bisexual men in the US. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1390–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1370-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grov C, Rendina HJ, Whitfield TH, Ventuneac A, Parsons JT. Changes in familiarity with and willingness to take preexposure prophylaxis in a longitudinal study of highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. LGBT Health. 2016;3(4):252–7. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelley CF, Kahle E, Siegler A, et al. Applying a PrEP continuum of care for men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(10):1590–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Lassiter JM, Whitfield THF, Starks TJ, Grov C. Uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national cohort of gay and bisexual men in the United States: The Motivational PrEP Cascade. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2017;74(3):285–292. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rendina HJ, Whitfield THF, Grov CS, TJ, Parsons JT. Distinguishing hypothetical willingness from behavioral intentions to initiate HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Findings from a large cohort of gay and bisexual men in the U.S. Soc Sci Med. 2017;172:115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CDC. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infectionin the United States 2014. [Accessed April 25, 2016];A clinical practice guideline. 2014 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/prepguidelines2014.pdf.

- 16.Starks TJ, Grov C, Parsons JT. Sexual compulsivity and interpersonal functioning: sexual relationship quality and sexual health in gay relationships. Health Psychol. 2013;32(10):1047–56. doi: 10.1037/a0030648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rusbult CE, Van Lange PA. Interdependence, interaction, and relationships. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003;54:351–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis MA, Gladstone E, Schmal S, Darbes LA. Health-related social control and relationship interdependence among gay couples. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(4):488–500. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoff CC, Beougher SC. Sexual agreements among gay male couples. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39:774–87. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9393-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grov C, Starks TJ, Rendina HJ, Parsons JT. Rules about casual sex partners, relationship satisfaction, and HIV risk in partnered gay and bisexual men. J Sex Marital Ther. 2014;40(2):105–22. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2012.691948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoff CC, Beougher SC, Chakravarty D, Darbes LA, Neilands TB. Relationship characteristics and motivations behind agreements among gay male couples: Differences by agreement type and couple serostatus. AIDS Care. 2010;22(7):827–35. doi: 10.1080/09540120903443384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons JT, Starks TJ, DuBois S, Grov C, Golub SA. Alternatives to monogamy among gay male couples in a community survey: Implications for mental health and sexual risk. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(2):303–12. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9885-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mimiaga MJ, Closson EF, Kothary V, Mitty JA. Sexual partnerships and considerations for HIV antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis utilization among high-risk substance using men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(1):99–106. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0208-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell JW, Petroll AE. HIV testing rates and factors associated with recent HIV testing among male couples. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(5):379–81. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182479108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephenson R, White D, Darbes L, Hoff CC, Sullivan P. HIV testing behaviors and perceptions of risk of HIV infection among MSM with main partners. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:553–60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0862-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell JW, Harvey SM, Champeau D, Seal DW. Relationship factors associated with HIV risk among a sample of gay male couples. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):404–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9976-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamarel KE, Golub SA. Intimacy motivations and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adoption intentions among HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) in romantic relationships. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(2):177–86. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9646-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephenson R, Freeland R, Finneran C. Intimate partner violence and condom negotiation efficacy among gay and bisexual men in Atlanta. Sex Health. 2016 doi: 10.1071/SH15212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koester KA, Liu A, Eden C, et al. Acceptability of drug detection monitoring among participants in an open-label pre-exposure prophylaxis study. AIDS Care. 2015;27(10):1199–204. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1039958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldenberg T, Stephenson R, Freeland R, Finneran C, Hadley C. ‘Struggling to be the alpha’: Sources of tension and intimace partner violece in same-sex relationships between men. Cult Health Sex. 2016;18(8):875–89. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1144791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rendina HJ, Moody RL, Ventuneac A, Grov C, Parsons JT. Aggregate and event-level associations between substance use and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men: Comparing retrospective and prospective data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parsons JT, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Botsko M, Golub SA. Predictors of day-level sexual risk for young gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1465–77. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parsons JT, Starks TJ. Drug use and sexual arrangements among gay couples: Frequency, interdependence, and associations with sexual risk. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(1):89–98. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drumright LN, Patterson TL, Strathdee SA. Club drugs as causal risk factors for HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men: A review. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(10-12):1551–601. doi: 10.1080/10826080600847894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grov C, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. In the shadows of a prevention campaign: Sexual risk behavior in the absence of crystal methamphetamine. AIDS Educ Prev. 2008;20(1):42–55. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oldenburg CE, Mitty JA, Biello KB, et al. Differences in attitudes about HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use among stimulant versus alcohol using men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1451–60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1226-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grov C, Cain D, Whitfield TH, et al. Recruiting a U.S. national sample of HIV-negative gay and bisexual men to complete at-home self-administered HIV/STI testing and surveys: Challenges and Opportunities. Sex Res Social Policy. 2016;13(1):1–21. doi: 10.1007/s13178-015-0212-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grov C, Cain D, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Parsons JT. Characteristics associated with urethral and rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia diagnoses in a US national sample of gay and bisexual men: Results from the One Thousand Strong panel. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(3):165–71. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsons JT, Starks TJ, Gamarel KE, Grov C. Non-monogamy and sexual relationship quality among same-sex male couples. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26(5):669–77. doi: 10.1037/a0029561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test: An update of research findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(2):185–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1991;7:363–71. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR, editors. Validity of the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) in inpatient substance abusers: Problems of drug dependence. 53rd Annual Scientific Meeting from the Committee on Problems of Drug Dependence Inc: 1991; Rockville, MD. Department of Health and Human Services; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenwood GL, Relf MV, Huang B, Pollack LM, Canchola JA, Catania JA. Battering victimization among a probability-based sample of men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(12):1964–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.12.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):939–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sullivan PS, White D, Rosenberg ES, et al. Safety and acceptability of couples HIV testing and counseling for US men who have sex with men: A randomized prevention study. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2014;13(2):135–44. doi: 10.1177/2325957413500534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duncan DT, Goedel WC, Stults CB, et al. A study of intimate partner violence, substance abuse, and sexual risk behaviors among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in a sample of geosocial-networking smartphone application users. Am J Mens Health. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1557988316631964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stults CB, Javdani S, Greenbaum CA, Kapadia F, Halkitis PN. Intimate partner violence and sex among young men who have sex with men. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(2):215–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beymer MR, Weiss RE, Halkitis PN, et al. Disparities within the disparity-determining HIV risk factors among latino gay and bisexual men attending a community-based clinic in Los Angeles, CA. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2016;73(2):237–44. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldenberg T, Finneran C, Andes KL, Stephenson R. ‘Sometimes people let love conquer them’: How love, intimacy, and trust in relationships between men who have sex with men influence perceptions of sexual risk and sexual decision-making. Cult Health Sex. 2015;17(5):607–22. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.979884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, et al. What's love got to do with it? Explaining adherence to oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-serodiscordant couples. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2012;59(5):463–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824a060b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]