Abstract

Mesophilic α-amylase from Flavobacteriaceae (FSA) is evolutionary closely related to thermophilic archaeal Pyrococcus furiosus α-amylase (PWA), but lacks the high thermostability, despite the conservation of most residues involved in the two-metal (Ca, Zn) binding center of PWA. In this study, a disulfide bond was introduced near the two-metal binding center of FSA (designated mutant EH-CC) and this modification resulted in a slight improvement in thermostability. As expected, E204G mutations in FSA and EH-CC led to the recovery of Ca2+-binding site. Interestingly, both Ca2+- and Zn2+-dependent thermostability were significantly enhanced; 153.1% or 50.8% activities was retained after a 30-min incubation period at 50 °C, in the presence of Ca2+ or Zn2+. The C214S mutation, which affects Zn2+-binding, also remarkably enhanced Zn2+- and Ca2+- dependent thermostability, indicating that Ca2+- and Zn2+-binding sites function cooperatively to maintain protein stability. Furthermore, an isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) analysis revealed a novel Zn2+-binding site in mutant EH-CC-E204G. This metal ion cooperation provides a possible method for the generation of α-amylases with desired thermal properties by in silico rational design and systems engineering, to generate a Zn2+-binding site adjacent to the conserved Ca2+-binding site.

Introduction

In the field of biotechnology, there is an increasing interest in engineering proteins with enhanced thermostability and altered activity1–3. This requires a comprehensive understanding of the determinants of thermostability. By comparing the microscopic stability features of mesophilic and thermophilic protein homologs, various mechanisms underlying stabilization and adaptive mutations in thermophilic enzymes that determine the overall rigidity have been identified4, revealing common factors contributing to thermostability, such as the number of disulfide bonds, a high core hydrophobicity5, salt bridge formation1, metal-binding activity, ionic interactions6,7, and an improved quality of packing8.

Starch-hydrolyzing α-amylases (EC 3.2.1.1) are widely used for various industrial applications, e.g., in starch saccharification, textiles, food products, fermentation, the preparation of ethanol as fuel, as well as in clinical, medical, and analytical chemistry9. Based on the sequence similarity and classification in the Carbohydrate-Active Enzyme (CAZy) database (www.cazy.org)10, the vast majority of α-amylases belong to the glycoside hydrolase family 13 (GH13), which includes 40 subfamilies11. In agreement with their origins, most GH13_5 α-amylases are bacterial, but the GH13_6 and GH13_7 subfamilies include plant and archaeal α-amylases12. However, due to their close relationship with some thermophilic archaeal α-amylases13, some Flavobacteriaceae α-amylases have been assigned to GH13_7, e.g., the α-amylase FSA we described previously14.

With a general structure characterized by three domains, all GH13 α-amylases adopt a (β/α)8-barrel fold as a catalytic domain (i.e., domain A), with a catalytic triad formed by two consensus Asp residues and a Glu residue15. Based on a sequence alignment and site mutations, a short, conserved stretch covering the β1 strand of the catalytic (α/β)8-barrel has been found in many α-amylases, with the FYW compositions in archaeal α-amylases, FNW in plant-derived α-amylases, and FEW in animal-derived α-amylases16. Furthermore, Tyr39 in Thermococcus hydrothermalis has been demonstrated to contribute to thermostability17.

Thermostable (thermophilic) α-amylases are highly attractive for commercial use and have received increasing attention in industrial fields, and for studies of the physical mechanisms underlying the thermal stability of proteins18. The successfully resolved crystal structures of some Bacillus α-amylases, such as Bacillus subtilis (BSUA), B. amyloliquefaciens (BAA), and B. licheniformis (BLA)19–21, have led to the confirmation of various proposals regarding the stabilizing role of structural features18. A conserved Ca2+-binding site, located at the interface between domains A and B, confers protein stability. It is well-known that domain B is the least conserved region in the α-amylase family, with the most variation in length and sequence22. However, with a few exceptions, this Ca2+-binding site is conserved in most GH_13 family α-amylases, and is essential for retaining protein structure and catalytic activity18,23. Some Ca2+-independent α-amylases also have been reported, and these show great advantages compared to Ca2+-dependent α-amylases24–26. Crystallographic analysis of thermophilic and Ca2+-independent P. furiosus α-amylase (PWA) also uncovered a conserved Ca2+-binding site located at the interface between domains A and B27. Another metal ion, Zn2+, has also been detected near this Ca2+-binding site in domain B, and forms a novel two-metal center, i.e., a (Ca, Zn)-binding site. Mutagenesis of the cysteine (Cys166) in the Zn2+-binding site results in a drastic reduction of PWA catalytic activity at high temperatures28. Therefore, it is speculated that both sites of this two-metal center are involved in stabilizing the catalytically active conformation of PWA at high temperatures27. Based on a sequence alignment, a similar (Ca, Zn) center was also predicted in some hyperthermophilic α-amylases from Thermococcus species, such as the recently reported α-amylase from Thermococcus sp. HJ2129. However, the functional mode of this two-metal center, and potential synergistic effects are unclear.

In our previous work, a novel α-amylase, was identified from a novel Flavobacteriaceae species. Using the CAZy database10, FSA was assigned to the GH13_7 subfamily; it is phylogenetically related to archaeal PWA (sequence identity, 48%), but not to other bacterial α-amylases14,30. Based on a sequence alignment, most residues involved in Ca2+ and Zn2+ binding are conserved in FSA. In the present study, the stabilizing function of this two-metal site was investigated by constructing a series of mutants and by an isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) analysis.

Results

Influence of Ca2+ and Zn2+ on the activity and thermostability of wild-type FSA

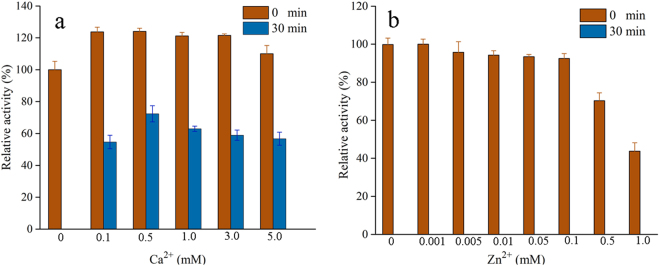

The α-amylase activity of FSA was measured in the absence or presence of various concentrations of Ca2+ and Zn2+. As shown in Fig. 1a, the α-amylase activity of FSA was moderately enhanced by the addition of Ca2+; approximately 120% activity was detected in the presence of Ca2+ (ranging from 0.1 mM to 5 mM). To evaluate the thermostability, all KH2PO4-Na2HPO4 reaction mixtures were substrate-free and were incubated at 50 °C for 30 min, with the indicated concentrations of Ca2+ or Zn2+. In the absence of Ca2+, FSA showed the complete loss of activity after 30 min of incubation. Conversely, remarkably higher residual activities were detected in the presence of Ca2+ at concentrations of 0.1 to 5 mM. Supplementation with 0.5 mM Ca2+ resulted in the highest activity (74.5%) after 30 min of incubation. In contrast to the positive effect of Ca2+ on FSA activity and thermostability, only marginally increased activity was observed in the presence of low concentrations of Zn2+, and activity was remarkably inhibited in the presence of 0.5 mM Zn2+ (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Influence of Ca2+ (a) or Zn2+ (b) on the FSA activity. Enzyme activity was measured after pre-incubation the starch-free reaction mixtures with 0.5 mM Ca2+, 0.01 mM Zn2+, at 50 °C for 0 min and 30 min, respectively. For relative activity calculation, the activity of FSA in the absence of metal ions and without pre-incubation was set as 100%.

Influence of Ca2+ and Zn2+ on the thermostability of FSA mutants

With the aim of reconstructing the two-metal (Ca, Zn) center observed in PWA and enhancing thermostability, a series of mutations involving Ca2+ and Zn2+ binding sites were evaluated (Fig. 2). Obviously, these mutations did not influence protein expression; clear, single bands of 52 kDa were detected by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (Figure S1), indicating that the expression levels for all constructs were similar to those FSA.

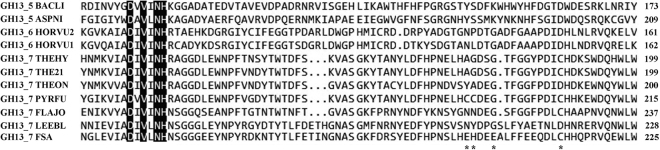

Figure 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of FSA and amylases from GH13_5, 13_6, and 13_7 subfamilies by ClustalX. The mutated residues in this study are marked as *. B. licheniformis, BACLI; Aspergillus niger, ASPNI; Hordeum vulgare, HORVU1; Hordeum vulgare, HORVU2; T. hydrothermalis, THEHY; T. sp. HJ21, THE21; T. onnurineus, THEON; P. furiosus, PYRFU; Flavobacterium johnsoniae, FLAJO; Leeuwenhoekiella blandensis, LEEBL; FSA, present study.

It has been reported that a disulfide bond adjacent to the Zn2+-binding site was engaged between Cys163 and Cys164 in PWA27. This disulfide bond was unusual in the sequences included in the comparative analysis, as shown in Fig. 2, and was suspected to be functional in maintaining the rigidity of PWA at higher temperatures27. In this study, we first introduced a disulfide bond by constructing a mutant of EH-CC, in which Glu200 and His201 in FSA were both replaced with Cys. Consequently, this mutation resulted in a detectable increase in activity and thermostability, with minor activity (3.2%) after 30 min of incubation at 50 °C.

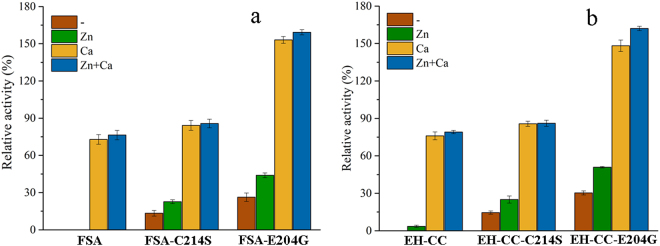

Further site-directed mutations involving this two-metal binding site were then evaluated, using wild-type FSA or mutant EH-CC as the template. When compared to the Zn2+-binding residues, site 214 displayed high conservation (Asp or Cys), but lacked subfamily specificity (Fig. 2). To alter Zn2+ binding in FSA, site Cys214 was replaced with Ser or Asp, and thereby four mutants were constructed from FSA and EH-CC. As a result, the replacement of Cys214 with the charged Asp led to the complete loss of enzyme activity (data not shown), despite a high level of protein expression (Figure S1). Conversely, high enzyme activity was retained after the replacement with Ser in FSA-C214S and EH-CC-C214S mutants, and thermostability was unexpectedly enhanced, with 13.4% and 9.3% residual activity detected after the 30-min incubation period. It is noteworthy that both C214S mutants exhibited obvious Zn2+-stimulated stability, and approximately 20% of the activity was retained by the addition of 0.01 mM Zn2+. In addition, the thermostability of these two C214S mutants was obviously enhanced by the presence of Ca2+, with higher residual activity (84.2% and 85.7%) in the FSA and EH-CC mutants (Fig. 3a and b).

Figure 3.

Relative activities of FSA and EH-CC variants in the presence of Ca2+ and Zn2+. (a) FSA and its mutants; (b) EH-CC and its mutants. The activity was measured after pre-incubating the starch-free reaction mixtures with 0.5 mM Ca2+, 0.01 mM Zn2+, or both ions, at 50 °C for 30 min. The activity of FSA in the absence of metal ions and without pre-incubation was set as 100%.

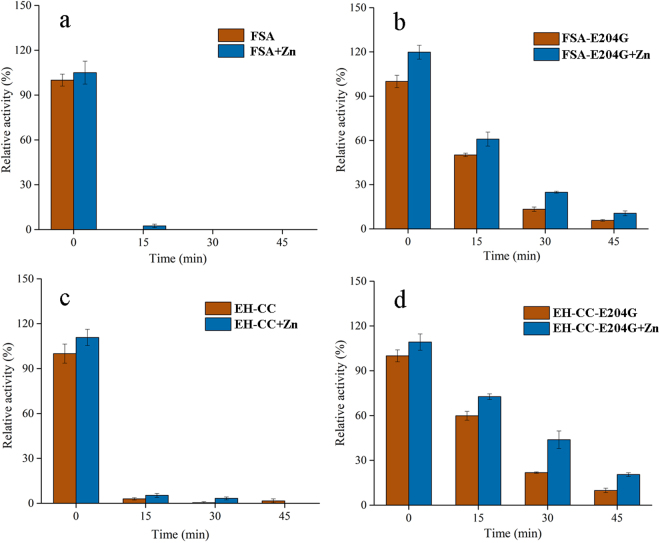

In the alignment of the two-metal (Ca, Zn) center, all sequences of GH13_6 and GH13_7 α-amylases, except FSA, possessed a conserved Gly for Ca2+-binding (Fig. 2). The corresponding residue was replaced with Glu (G204) in the sequence of FSA. By site-directed mutagenesis, the replacement of Glu204 with Gly resulted in a remarkable increase in thermostability, with 50.2% and 59.9% activity retained in FSA-E204G and EH-CC-E204G, respectively, after 15 min of incubation in the absence of any metal ions (Fig. 4). Of note, the Ca2+-mediated stimulation of thermostability was greatly enhanced after the introduction of this mutation. Compared to its initial activity without the addition of any metal ion, FSA-E204G exhibited a remarkably high activity of 153.1% after 30 min of incubation at 50 °C in the presence of Ca2+. Furthermore, EH-CC-E204G exhibited a higher thermostability than that of FSA-E204G, implying that the mutant has a much more stable structure (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, Zn2+ had a positive effect on the constructs with a mutation at site 204, with 44.0% activity for FSA-E204G, and a higher residual activity (50.8%) in EH-CC-E204G after the 30-min incubation period.

Figure 4.

Influence of Zn2+ on the thermostability of FSA (a) and FSA-E204G (b), EH-CC (c) and EH-CC-E204G (d). The activity was measured after pre-incubating the starch-free reaction mixtures with 0.01 mM Zn2+ at 50 °C and sampled interval for activity measurement. The measured activity of FSA in the absence of metal ions and without pre-incubation was set as 100%.

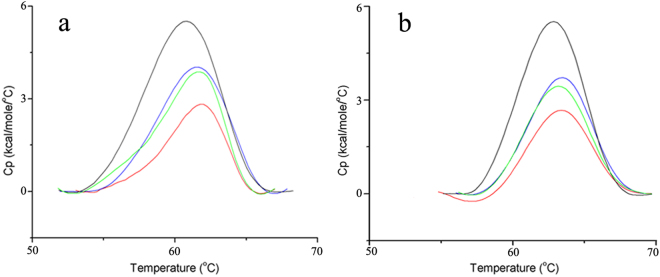

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis of the thermal stability of FSA and EH-CC-E204G

DSC experiments were performed using purified FSA and EH-CC-E204G to quantitatively assess the effects of Ca2+ and Zn2+ on protein folding stability. DSC scans of each sample are shown in Fig. 5. Both proteins were stabilized by the addition of Ca2+ and Zn2+; an increase in the melting temperature (T m) from 60.5 °C to 61.3 °C was obtained for FSA in the presence of Ca2+, while the T m value increased to 61.1 °C in the presence of Zn2+ (Table 1). In agreement with the enzyme thermostability data, FSA retained the highest thermostability in the presence of both ions (61.5 °C). Compared to wild-type FSA, the replacement of Glu with Gly in EH-CC resulted in an enhanced T m value (62.7 °C), even without additional ions. Furthermore, supplementation with Ca2+ also enhanced the T m value of EH-CC-E204G to 63.3 °C, whereas slightly weaker elevation was detected in the presence for Zn2+ (63.1 °C).

Figure 5.

DSC spectrums of the purified FSA (a) and EH-CC-E204G (b). The scanning profile in the absence of metal ions (black line), in the presence of 0.5 mM Ca2+ (blue line), 0.01 mM Zn2+ (green line), and both ions (red line). Using the dialysis buffer as the reference, 0.8 mg ml−1 of FSA and EH-CC-204 were scanned from 20 to 90 °C.

Table 1.

T m values of FSA and EH-CC-E204G determined by DSC analysis. “−” represents no metal ion addition, each sample were measured for three times and the systematic errors for these measurement are ± 0.2 °C.

| FSA (°C) | EH-CC-E204G (°C) | |

|---|---|---|

| − | 60.5 | 62.7 |

| Zn2+ | 61.1 | 63.1 |

| Ca2+ | 61.3 | 63.3 |

| Ca2+ + Zn2+ | 61.5 | 63.4 |

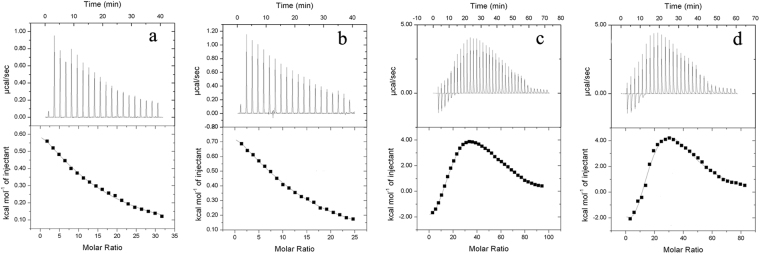

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) analysis

Titration of 15 mM CaCl2 into FSA and EH-CC-E204G resulted in endothermic and monophasic isotherm. As shown in Fig. 6a and b, the best fit model for the ITC data was a one-set binding sites model showing that at least one Ca2+ binds enthalpically to FSA with a low affinity (K d = 746.3 μM and ΔH = 1.3 kcal/mol), and a higher affinity was observed for EH-CC-E204G (K d = 653.6 μM and ΔH = 1.2 kcal/mol).

Figure 6.

Isothermal titration microcalorimetric analysis of Ca2+ and Zn2+ binding to FSA (a,c) and EH-CC-E204G (b,d). Trace of the calorimetric titration of 20 × 2-μl aliquots of 15 mM CaCl2 or 30 (36) × 1-μl aliquots of 15 mM ZnCl2 into 50 μM proteins (top), and integrated binding isotherms (bottom).

The titration of ZnCl2 into these two proteins resulted in a multiphasic calorimetric isotherm that was best fit by the sequential binding model. In the isothermal comparison between FSA and EH-CC-E204G (Fig. 6c and d), it is noteworthy that one additional site (site 4) was observed in the titration profile of EH-CC-E204G, implying that this site might be the Zn2+-binding site in the two-metal region. This endothermic reaction showed a high dissociation constant for Zn2+ binding (K d4 = 1422.5 μM, ΔH 4 = 260.8 kcal/mol), indicating that the created Zn2+-binding site can bind to Zn2+, but with low affinity. This is in agreement with the modest increased thermostability of those E204G mutants when in the presence of Zn2+. In addition to this novel binding site, the isotherm of Fig. 6c exhibited an initial exothermic phase (K d1 = 1642.0 μM, ΔH 1 = −108.3 kcal/mol) representing stoichiometric Zn2+ binding to a low-affinity site, followed by a second endothermic, another low-affinity binding site. Subsequent Zn2+ binding was an endothermic reaction with modest affinity to site 3 (K d3 = 444.4 μM). The last phase (site 5) in FSA was an exothermic phase and exhibited a similar affinity to that of site 1 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Thermodynamics of metal ions binding.

| Metal ion | Site | Parameter | FSA | EH-CC-E204G |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca2+ | Site 1 | K d (μM) | 746.3 | 653.6 |

| ΔH (kcal/mol) | 1.3 | 1.2 | ||

| Zn2+ | Site 1 | K d (μM) | 1642.0 | 724.6 |

| ΔH (kcal/mol) | −108.3 | −64.2 | ||

| Site 2 | K d (μM) | 2941.2 | 4524.9 | |

| ΔH (kcal/mol) | 185.4 | 6.9 | ||

| Site 3 | K d (μM) | 444.4 | 96.2 | |

| ΔH (kcal/mol) | 242.1 | 67.7 | ||

| Site 4 | K d (μM) | 1422.5 | ||

| ΔH (kcal/mol) | 260.8 | |||

| Site 5 | K d (μM) | 961.5 | 869.6 | |

| ΔH (kcal/mol) | −159.4 | −109.7 |

Discussion

The identification of various features underlying the stability of thermostable enzymes remains a subject of ongoing study18. Mesophilic FSA from bacteria is evolutionary closely related to thermophilic archaeal PWA, but displays a sharply decreased thermostability, thus providing an ideal target for revealing strategies for the adaption of this mesophilic protein to a mesophilic environment. As an important signal for lateral gene transfer from PWA to FSA, the uncommon (Ca, Zn) two-metal center only exists in a few GH13_7 α-amylases, including PWA and those of some Thermococcus species27,29,31,32. By site-directed mutagenesis, both Ca2+- and Zn2+-binding sites were found to be important for the thermostability of PWA27,28. As these two sites are in close proximity, we suspected that they might function cooperatively in retaining the rigidity of the protein under higher temperature conditions.

To gain further insight into the function of this two-metal center, we first generated a mutation in EH-CC around the Zn2+-binding center by introducing a disulfide bond. This disulfide bond is adjacent to the Zn2+-binding site in PWA and rigidifies the active site area at high temperatures27. However, the molecular roles of this disulfide bond on thermostability of PWA remains to be experimental verified. In this study, a slightly enhanced thermostability observed in the EH-CC mutant implies that this disulfide bond contributes to the protein stabilization under restrict temperatures. Furthermore, the thermostability of EH-CC-derived proteins showed higher Zn2+-dependence than those of FSA and FSA-derived mutants. In the PWA structure, this disulfide bridge is in close vicinity to the zinc-binding site, these findings raise the possibility that this disulfide bond relating to the Zn2+ binding and ensuring a compact FSA structure. In PWA, besides the conserved Ca2+ located at the interface between domain A and B, another anomalous signal matching Zn2+ was detected near the Ca2+-binding site27. In contrast, the undetectable Zn2+ stimulation of FSA suggested that tight Zn2+-binding or no binding occurs in the FSA structure. Among three residues that act as Zn2+-binding residues, a mutation of Cys165 to Ser dramatically decreased the thermostability of PWA at 115 °C28. Conversely, the same mutation (C214S) in FSA not only resulted in an increased thermostability, but also enhanced the Zn2+-induced stimulation of thermostability. An explanation for this stimulation is that no Zn2+ binds to the wild-type FSA protein, and the replacement of Cys with Ser facilitates this binding. Meanwhile, the substitution of Cys214 with Asp completely abolished the activities of FSA and EH-CC, further demonstrating the important roles of this site in retaining the protein folding of FSA.

In the PWA structure, totally eight residues are binding amino acids involved in the two-metal center27. Based on a multiple alignment, we found only one residue (Gly204) was substituted by Glu in FSA. High conservation of this site in the α-amylases of GH13_6 and GH13_7 implies that this site is critical to the thermostability of these proteins. In this study, the replacement of Glu204 with Gly greatly enhanced the thermostability of EH-CC-E204G in the absence of any metal ions. In addition, the Ca2+-dependence of two E204G mutants became much higher than that of their parental proteins, demonstrating that mutations at this site may contribute to Ca2+-binding and further stabilize the protein. Interestingly, the modest enhanced Zn2+-stimulated thermostability, together with the appearance of a novel binding site after titration of Zn2+ into EH-CC-E204G, implied that the Zn2+ binding site was also resumed. This provides further evidence for the cooperative functions of this two-metal center in maintaining the protein rigidity and stability. However, both ion binding affinities revealed by ITC analysis are much lower, indicating that the pockets for Ca2+ and Zn2+ binding need to be further addressed. In FSA, we suspected that Ca2+ can bind to this two-metal region but with very low affinity, while no Zn2+ binding occurs at this site. Mutant EH-CC-E204G creates a relative compact binding pocket for Ca2+ and Zn2+ accommodation, and thereby gains an improved thermostability upon these two ions. However, in compared to PWA, these binding affinities are much lower and need to be improved in our future work.

In summary, most residues involving the (Ca, Zn) two-metal center in the thermophilic archaeal α-amylase PWA are also found in its mesophilic homolog, FSA. In the mesophilic environment, FSA retained most of its residues for ion binding but lost its thermostability during evolution. Mutations leading to the reconstruction of this two-metal center suggested that these two ion binding sites have synergistic effects. As most α-amylases contain a conserved Ca2+, this synergic cooperation provides a basis for designing engineered α-amylases with desired thermal properties, by in silico rational design and the systems engineering of a Zn2+-binding site adjacent to the Ca2+-binding site.

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and materials

Escherichia coli DH5α was used for plasmid construction and E. coli BL21-CodonPlus was used to express FSA and mutants. Unless otherwise indicated, recombinant strains were cultured in the Luria-Bertani (LB) medium consisting of 1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% NaCl (pH 7.0).

Sequence alignment and mutant construction

Some α-amylases encoding sequences from GH13_5, 13_6, and 13_7 subfamilies were extracted from NCBI and aligned by ClustalX33. Gene splicing by overlap extension PCR (SOE-PCR) was used for site-directed mutagenesis34. All the primers used for mutant generating were listed in Table S1. According to the corresponding sequence of PWA, Glu200 and His201 in FSA were replaced by Cys, which resulted in a double mutant designated as EH-CC. Then, other mutants involving in Ca2+ or Zn2+ binding site were generated on the basis of FSA or EH-CC, respectively. The PCR product was ligated into pGM-18T vector (Promega), and transformed into E. coli 5α for sequencing. Correct plasmid was digested, ligated into the expression vector pETDuet-1, and transformed into E. coli BL21-CodonPlus for protein expression.

Protein expression and purification

The E. coli BL21-CodonPlus recombinants were cultivated in LB medium with 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin and 40 μg ml−1 chloromycetin. When reaching at the mid-exponential growth phase, cells were induced by isopropyl-β-Dthiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at a final concentration of 1 mM. After incubated at 16 °C, cells were harvested, washed and resuspended as we previously described14. For enzyme activity assay, the purified proteins were prepared by passing through a His-trap column. For DSC analysis, proteins with high purity were obtained by a three-step purification procedure14. The resulting protein fractions were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE. The protein concentration was determined by coomassie brilliant method.

Influences of Ca2+ and Zn2+ on the α-amylase’s activity and thermal stability

α-Amylase activity was determined by measuring the amount of reducing sugar released during the enzymatic hydrolysis of 5 g l−1 of soluble starch in 50 mM PBS (pH 6.0) at 50 °C for 15 min. Reducing sugar was measured by a modified dinitrosalicylic acid method35. One unit of α-amylase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 μmol of reducing sugar as glucose per minute under the assay conditions36. For thermostability assay, enzymes were diluted to a final concentration of 10 μg mg−1 in buffer A and the assay mixtures were incubated at 50 °C for 30 min. The residual activity was measured as standard procedures described above, in the presence or absence of indicated concentrations of Ca2+ and (or) Zn2+.

DSC analysis for thermal stability

Proteins from Superdex-200 were dialyzed overnight in buffer consisting of 20 mM Hepes, and concentrated by ultrafiltration. After degassing by stirring under vacuum prior to scanning, samples in the MicroCal VP-DSC (Malven) were cooled down to 20 °C and gradually heated, at a scan rate of 1.5 °C min−1. Using the dialysis buffer as a baseline, 0.8 mg ml−1 of FSA and EH-CC-204 were scanned from 20 to 90 °C, in the absence or presence of 0.5 mM Ca2+, 0.01 mM Zn2+, or both ions. Using the Origin software from MicroCal Inc, the thermal midpoints (T m) was analyzed by subtracting the baseline.

ITC analysis for Ca2+ and Zn2+ binding

ITC experiments were performed with a MicroCal VP-ITC microcalorimeter. The sample of FSA or EH-CC-E204G was placed in the sample cell, and the corresponding dialysis buffer was placed in the reference cell. The titrations CaCl2 and ZnCl2 solutions were prepared with the dialysis buffer and degassed in a ThermoVac apparatus (Microcal). Titrations were performed at 25 °C with protein concentrations between 50 and 60 μM. The titration isotherm was integrated by using the Origin software provided by Microcal Inc.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the grant from the Focus on research and development plan in Shandong province (2011GSF11715). We also thank Jing Zhu and Zhifeng Li from Shandong University for the technical help in DSC and ITC analysis.

Author Contributions

Y.H.J. and Y.C.Y. designed the research. Y.H.J., Y.Z., N.X.Y., L.S.N., S.X.Y., G.C., W.Z.H. and Z.G.M. performed the experiments. Y.C.Y. and Y.H.J. wrote the manuscript. X.P. and Y.Z. revised the manuscript, all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-18085-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chakravarty S, Varadarajan R. Elucidation of factors responsible for enhanced thermal stability of proteins: a structural genomics based Study. Biochemistry. 2002;41:8152–8161. doi: 10.1021/bi025523t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.England JL, Shakhnovich BE, Shakhnovich EI. Natural selection of more designable folds: a mechanism for thermophilic adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:8727–8731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530713100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sammond DW, et al. Comparing residue clusters from thermophilic and mesophilic enzymes reveals adaptive mechanisms. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0145848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Stites WE. Replacement of staphylococcal nuclease hydrophobic core residues with those from thermophilic homologs indicates packing is improved in some thermostable proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;344:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gromiha MM, Pathak MC, Saraboji K, Ortlund EA, Gaucher EA. Hydrophobic environment is a key factor for the stability of thermophilic proteins. Proteins. 2013;81:715–721. doi: 10.1002/prot.24232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogt G, Woell S, Argos P. Protein thermal stability, hydrogen bonds, and ion pairs. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;269:631–643. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berezovsky IN, Shakhnovich EI. Physics and evolution of thermophilic adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:12742–12747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503890102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radestock S, Gohlke H. Protein rigidity and thermophilic adaptation. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2011;79:1089–1108. doi: 10.1002/prot.22946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Souza PM, Magalhues PO. Application of microbial α-amylase in industry–a review. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2010;41:850–861. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822010000400004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantarel BL, et al. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2009;37:233–238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majzlová K, Pukajová Z, Janeček S. Tracing the evolution of the α-amylase subfamily GH13_6 covering the amylolytic enzymes intermediate between oligo-1,6-glucosidases and neopullulanases. Carbohydr. Res. 2013;367:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stam MR, Danchin EG, Corinne R, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. Dividing the large glycoside hydrolase family 13 into subfamilies: towards improved functional annotations of α-amylase-related proteins. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2006;549:555–562. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janeček S, Svensson B, MacGregor EA. α-Amylase: an enzyme specificity found in various families of glycoside hydrolases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014;71:1149–1170. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li CF, et al. Close relationship of a novel Flavobacteriaceae α-amylase with archaeal α-amylases and good potentials for industrial applications. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2014;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janeček S. Amylolytic enzymes-focus on the alpha-amylases from archaea and plants. Nova Biotechnol. 2009;9:5–25. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janeček S. Sequence similarities and evolutionary relationships of microbial, plant and animal α-amylases. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994;224:519–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godány A, Majzlová K, Horváthová V, Janeček S. Tyrosine 39 of GH13 α-amylase from Thermococcus hydrothermalis contributes to its thermostability. Biologia. 2010;65:408–415. doi: 10.2478/s11756-010-0030-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prakash O, Jaiswal N. α-Amylase: an ideal representative of thermostable enzymes. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010;160:2401–2414. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8735-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alikhajeh J, et al. Structure of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens α-amylase at high resolution: implications for thermal stability. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F: Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2010;66:121–129. doi: 10.1107/S1744309109051938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Machius M, Wiegand G, Huber R. Crystal Structure of Calcium-depleted Bacillus licheniformis α-amylase at 2.2 Å Resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;246:545–559. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kagawa M, Fujimoto Z, Momma M, Takase K, Mizuno H. Crystal structure of Bacillus subtilis alpha-amylase in complex with acarbose. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:6981–6984. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.23.6981-6984.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janecĕk S. alpha-Amylase family: molecular biology and evolution. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1997;67:67–97. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6107(97)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boel E, et al. Calcium binding in alpha-amylases: an X-ray diffraction study at 2.1-Å resolution of two enzymes from Aspergillus. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6244–6249. doi: 10.1021/bi00478a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koch R, Zablowski P, Spreinat A, Antranikian G. Extremely thermostable amylolytic enzyme from the archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990;71:21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb03792.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nonaka T, et al. Crystal structure of calcium-free α-amylase from Bacillus sp. strain KSM-K38 (AmyK38) and its sodium ion binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:24818–24824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212763200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sajedi RH, Taghdir M, Naderimanesh H, Khajeh K, Ranjbar B. Nucleotide sequence, structural investigation and homology modeling studies of a Ca2+-independent alpha-amylase with acidic pH-profile. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007;40:315–324. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2007.40.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linden A, Mayans O, Meyer-Klaucke W, Antranikian G, Wilmanns M. Differential regulation of a hyperthermophilic α-amylase with a novel (Ca, Zn) two-metal center by zinc. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:9875–9884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savchenko A, Vieille C, Kang S, Zeikus JG. Pyrococcus furiosus α-amylase is stabilized by calcium and zinc. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6193–6201. doi: 10.1021/bi012106s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng HX, Luo ZD, Lu MS, Wang SJ. The hyperthermophilic α-amylase from Thermococcus, sp. HJ21 does not require exogenous calcium for thermostability because of high-binding affinity to calcium. J. Microbiol. 2017;55:379–387. doi: 10.1007/s12275-017-6416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janeček S, Lévêque E, Belarbi A, Haye B. Close evolutionary relatedness of α-amylases from archaea and plants. J. Mol. Evol. 1999;48:0421–0426. doi: 10.1007/PL00006486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leveque E, Haye B, Belarbi A. Cloning and expression of an alpha-amylase encoding gene from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Thermococcus hydrothermalis and biochemical characterization of the recombinant enzyme. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000;186:67–71. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(00)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim JK, et al. Critical factors to high thermostability of an α-amylase from hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus onnurineus NA1. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007;17:1242–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene. 1989;77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller GL. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959;31:426–428. doi: 10.1021/ac60147a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagihara H, et al. Novel α-amylase that is highly resistant to chelating reagents and chemical oxidants from the alkaliphilic Bacillus isolate KSM-K38. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:1744–1750. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.4.1744-1750.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).