Abstract

To better understand the relationship between the environmental variables and microbial communities of activated sludge, we took winter samples from different biological treatment units (anaerobic, oxic, etc) from the WWTP’s of a number of Chinese cities. Differences in influent organic components and activated sludge microbial communities were identified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and high-throughput sequencing technology, respectively. Liquid nitrogen grinding pretreatment of samples was found to aid in the obtaining of a more bio-diversified sample. Influent type and dissolved oxygen concentration influenced the activated sludge microbial community structure. Nitrospira, Caldilineaceae and Anaerolineaceae were highly related to domestic wastewater treatment systems, whereas Thauera was the most abundant putative refractory aromatic hydrocarbon decomposer found in industrial wastewater treatment systems. Within the influent composition, we speculate that Thauera, Macellibacteroides and Desulfomicrobium are the key functional genera of the anaerobic environment of the textile dyeing industry wastewater treatment systems, whilst Thauera and Thiobacillus are key functional microbes in fine chemical wastewater treatment systems.

Introduction

During Eastern China’s recent and rapid urbanization and industrialization, there has been a rise in a number of different competitive industries. Over the past few decades these have often been concentrated at various industrial parks. In Shaoxing city, for example, textile dyeing is one of the mainstay industries concentrated within the Coastal Development Zone. Similarly, in Shangyu city, located within the Hangzhou Bay Economic Development Zone, many fine chemical industries have been established, particularly those producing synthetic organic dyes, pharmaceuticals, agro-chemicals, textile auxiliaries, and similar. To avoid environmental pollution, a series of supporting facilities have also been built. Among them, wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) play crucial roles in the environmental protection of local waters.

The WWTPs in Eastern China receive most of their specific influent as large scale industrial wastewater from local industries. This is a different situation from that of many of the normal municipal WWTPs occurring elsewhere. In comparison to domestic wastewater treatment systems, these plants often receive much higher levels of refractory organic pollutants from textile dyeing and fine chemical industries. It is exactly this that is causing a serious threat to the normal operation of the Shaoxing and Shangyu WWTPs1. Activated sludge (AS) is the key to the operation of municipal WWTPs, so an in-depth knowledge of the microbial communities and their interactions will help improve the design and efficiency of WWTPs2. Since the 1990 s, techniques derived from molecular biology, such as Denaturing Gel Gradient Electrophoresis and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, have been utilized to probe the microbial community structure in many contexts3. In a study using such molecular biotechnological methods, Yang and colleagues looked at two WWTPs of northern China and found that Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes were the 3 most abundant phylogenetic groups at the phylum level, with Nitrosomonas, Thauera and Dechloromonas the specific key genera present1. However, these molecular methods were somewhat limited due to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) bias and low sequencing depth4. More recently, high-throughput sequencing offers the opportunity of a deeper and more accurate characterization of the microbial communities of environmental samples, than using the previous molecular biological techniques5,6. Of these newly developed high-throughput sequencing technologies, the 454 Roche platform (pyrosequencing) seems to be the most commonly used method. However, Illumina sequencing can achieve even higher throughput for samples7. Using the Illumina HiSeq sequencing platform in 2016, 63 genera were found to constitute the core community of 13 Danish WWTPs. Of these, the genus Nitrotoga was identified as the primary nitrite-oxidizer, rather than Nitrospirae 8. Although such studies represent great advances in microbial community analysis technology, they have usually been focused upon the microbial communities of only one particular category of wastewater treatment system9,10 and/or on aerobic units4,8,11,12. However, takes aerobic units as the representative of entire waste-water treatment system should be experimental demonstrated because different biological treatment units takes different function, like nitrification usually happened in aeration tank, whereas denitrification mostly happened in anaerobic tank13. Moreover, researchers have sometimes overlooked the DNA extraction bias against Gram positive bacteria when using standard extraction protocols14,15. In this, the sample DNA is extracted using a commercial isolation kit, in which the cell lysis solution consists of SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfonate). However, SDS is not so effective for Gram-positive bacteria because of the differing cell wall structure and composition of such bacteria16. Thus, it is worthwhile to investigate microbial community structure in different types of WWTPs and reveal their differences using more comprehensive methods.

In another aspects, in comparison to ordinary domestic sewage, the textile dyeing industry and fine chemical industry wastewaters contain plenty of auxiliary chemicals and dyes17,18. A quantitative understanding of such influent characteristic differences which may occur in full-scale domestic sewage treatment systems and may relate specifically to textile-dyeing industrial wastewater treatment systems, is rare. Similarly, the differences between textile dyeing industrial wastewater and fine chemical industrial wastewater have not been adequately considered.

To better understand the relationship between environment variables and microbial communities, we obtained activated sludge from four different WWTPs. These represented WWTPs mainly treating either textile dyeing wastewater, fine chemical wastewater or domestic wastewater. We then analyzed the influent component and the microbial community structure based on the results of GC-MS and high-throughput sequencing, respectively. The main objectives were (1) to find out the core microbes in different WWTPs; (2) to compare the microbial community and dominant bacterial populations of different WWTPs; (3) to combine the influent characteristics data and identify the potential ecological roles of the most important phylotypes in detail. Additionally, the validation of some of the non-traditional research methods presented in this paper would afford a fundamental framework for future research on the activated sludge microbial communities of WWTPs.

Results

WWTP performance difference

The Qige and Xiangyang WWTPs are domestic sewage treatment systems with relative stable influent and effluent quality. In these, the entire removal efficiencies of chemical oxygen demand (COD) and total Kjeldhal nitrogen (T-N) were higher than those in the other industrial wastewater treatment systems (Table 1). In Shaoxing, the WWTP is mainly treating wastewater from the textile dyeing industry, where the proportion of textile dyeing industry wastewater is more than 80%. For the samples from Shaoxing, the pH ranged from 7 to 11, and the chromaticity was 250–400 times. The Shangyu WWTP mainly treats wastewater from the Shangyu industrial zone where the influent is primarily fine chemical industrial wastewater (about 85%) mainly from pharmaceutical, agro-chemical and pigment industries, with the remainder made of domestic wastewater. In this case the primary component was synthetic pigment.

Table 1.

Characteristic of all the WWTPs.

| Full name | The type of influent | Process | Sampling site | Code | DNA extraction method | Influent average of the month (or range) (mg/L) | Removal rate | sampling date | Temperature | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOD | COD | T-N (or NH4 + -N) | T-P | BOD | COD | TN | NH4-N | T-P | ||||||||

| Qi-ge II | Domestic sewage predominant | Inverted A2O | Oxic train | QG | Isolation Kit | 220 | 553.57 | 55 (TN); 40 (NH4 + -N) | 11 | 97% | 93.30% | 71.70% | 91.70% | 90.70% | 2015.01.24 | 10–18 °C |

| Xiang-yang | Domestic sewage predominant (20% industrial waste water) | Improved A2O | Oxic train | XY | Isolation Kit | / | 200–300 | 20 (NH4 + -N) | / | / | / | / | / | / | 2015.02.15 | 6–11 °C |

| XY_Gr | Liquid nitrogen grinding + Isolation Kit | |||||||||||||||

| Shao-xing I | Mainly dyeing wastewater (about 80%) | coagulation + A/O process (with sludge reflux) | Anaerobic train | SX_1_A | Isolation Kit | 148 | 437 | 77.5 (TN); 59.7 (NH4 + -N) | 6.74 | 94.50% | 77.80% | 65% | 98% | 97% | 2015.01.24 | 8–16 °C |

| Oxic train | SX_1_O | Isolation Kit | ||||||||||||||

| Shao-xing II | Mainly dyeing wastewater (about 85%) | Coagulation + oxidation ditch | Oxidation ditch | SX_2_O | Isolation Kit | 164 | 672 | 75.8 (TN); 65.3 (NH4 + -N) | 5.26 | 95.30% | 86% | 32.80% | 99% | 99% | 2015.01.24 | 8–16 °C |

| Shao-xing III | Same with Shao-xing I | Coagulation + anaerobic tank (oxidation ditch form) + oxidation ditch | Hydrolytic train | SX_3_A | Isolation Kit | same with I | 94.20% | 79.27% | 68% | 98.90% | 98.10% | 2015.01.24 | 8–16 °C | |||

| Oxidation ditch | SX_3_O | Isolation Kit | ||||||||||||||

| Shang-yu | Domestic sewage + Fine chemical industry waste water (about 55%) | Anaerobic hydrolyze + A/O (with sludge reflux) | Anoxic train | SY_A | Isolation Kit | 100–140 | 294 | 38.9 (NH4 + -N) | 7.47 | / | 0.42 | / | 85.19% | 14.60% | 2015.01.22 | 6–16 °C |

| Oxic train | SY_O | Isolation Kit | ||||||||||||||

BOD: biochemical oxygen demand; COD: chemical oxygen demand; T-N: total Kjeldhal nitrogen NH4+ −N: ammonia nitrogen; T-P: total phosphorus; A2O: anaerobic-anoxic-oxic; A/O: anaerobic- oxic.

The influent composition of Shaoxing, Shangyu and Qige were analyzed using GC-MS (Fig. 1). Organic compounds with relatively high peak abundances were identified by comparison with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) mass spectral library database. The results showed a significantly higher amount of organic pollutants observed in the industrial wastewater (Shaoxing, Shangyu) than in the domestic sewage treatment plant (Qige). There were totally 114, 84 and 40 organic pollutants found in Shangyu, Shaoxing and Qige respectively. Thereinto, Benzyloxybenzoic acid was detected in the raw influent of the Shangyu WWTP with significant abundances corresponding to the highest peaks at the retention time (R.T.) of 19.276 min. By contrast, no obvious organic compounds were found in the influent of Qige WWTP. In the Shaoxing WWTP, the main possible organic compounds found in the influent were 9-desoxo-9-x-acetoxy-3,8,12-tri-O-acetylingol, ethyl iso-allocholate, C32H54O2 (analog), C23H32O and phenol.

Figure 1.

TIC chromatogram of Shang-yu, Qi-ge and Shao-xing WWTP influent and the main possibly organic compounds. R.T = Retention Time.

α diversity (within-habitat diversity)

After filtering the low-quality reads using a RDP (ribosomal database project) classifier and trimming the adapters, barcodes and primers, 293,404 reads were assigned to bacterial 16 S rRNA gene sequences for the 10 samples. The reads, as selected above, were defined as ‘raw reads’ for each sample and the average length of all bacterial sequences without the primers was 443 bp. The number of assigned reads per sample was between 21,207 and 34,108. The operational taxonomic units (OTUs), Chao and ACE (abundance based coverage estimator) values are summarized in Table 2. The ACE, Chao and Shannon indexes demonstrated the richness of the microorganism community, the higher value indicating the greater richness. The activated sludge sample from the returned sludge of Qige had the highest diversity, with a Shannon index of 5.28. This was followed by the returned sludge from Xiangyang, with a Shannon index of 4.755. These two WWTPs both represent A2O processes (anaerobic-anoxic-oxic) where their influent is dominated by domestic sewage.

Table 2.

Values of OTUs, Chao 1 and ACE (Alpha-diversity index) in different WWTPs.

| Sample ID | Reads | OUT | ACE | Chao | Coverage | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QG | 29058 | 806 | 893(867,930) | 896(863,948) | 0.995802 | 5.28(5.26,5.29) | 0.0172(0.0165,0.0178) |

| SX-1-A | 33570 | 546 | 651(619,697) | 642(607,699) | 0.996425 | 4.1(4.08,4.12) | 0.0381(0.0375,0.0388) |

| SX-1-O | 24803 | 655 | 855(804,923) | 854(792,944) | 0.992219 | 4.13(4.1,4.15) | 0.0582(0.0564,0.06) |

| SX-2-O | 21207 | 588 | 694(662,738) | 727(677,806) | 0.993776 | 4(3.96,4.03) | 0.0991(0.0957,0.1026) |

| SX-3-A | 34099 | 570 | 657(629,696) | 683(641,751) | 0.996569 | 4.19(4.17,4.21) | 0.0434(0.0424,0.0445) |

| SX-3-O | 30613 | 611 | 709(679,751) | 751(700,833) | 0.995851 | 3.76(3.74,3.79) | 0.1303(0.1267,0.1338) |

| SY-A | 32098 | 545 | 606(585,640) | 634(596,700) | 0.997321 | 4.59(4.57,4.61) | 0.0278(0.0271,0.0284) |

| SY-O | 25636 | 478 | 525(507,553) | 533(508,578) | 0.997269 | 4.33(4.31,4.35) | 0.0379(0.0369,0.039) |

| XY | 34108 | 802 | 857(839,884) | 870(843,914) | 0.997068 | 4.68(4.65,4.7) | 0.0564(0.0546,0.0582) |

| XY-Gr | 28212 | 791 | 859(838,891) | 886(850,943) | 0.995824 | 4.83(4.8,4.85) | 0.046(0.0444,0.0477) |

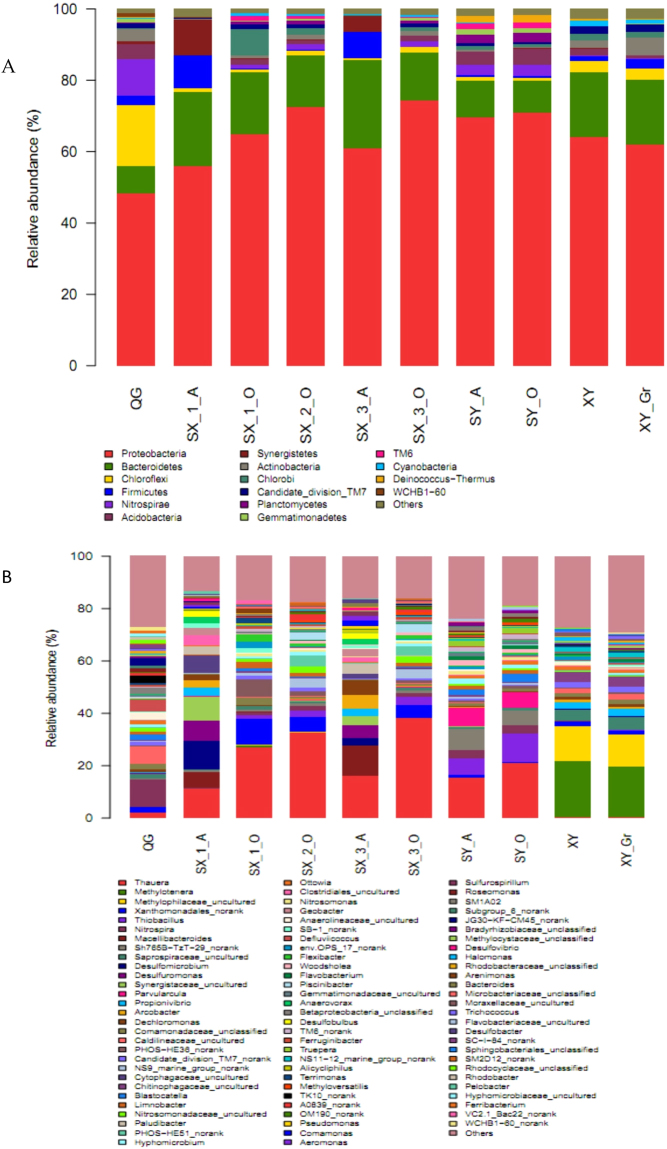

All effective bacterial sequences in each sample were assigned to levels from genus to phylum. At the phylum level (see Supplementary Material S1 and Fig. 2A), the most abundant phylum was Proteobacteria, incorporating 64.4% of the sequences on average (minimum 48.5% in QG and maximum 74.4% in SX_3_OD). The next major phyla were Bacteroidetes (mean 15.4%, 7.6–20%), Chloroflexi (mean 2.99%), Firmicutes (mean 2.46%), Nitrospirae (mean 2.15%), Acidobacteria (mean 1.99%), and Synergistetes (mean 1.5%). It is interesting that in the sample QG, of a domestic sewage treatment system, Chloroflexi was the second most abundant phylum, accounting for 17% of the total bacterial effective sequences, whereas Chloroflexi only averaged 1.4% across the other samples. Moreover, Nitrospirae represented 10.2% of the total bacterial effective sequences in QG, whereas Nitrospirae were rare in the other samples and no Nitrospirae was found in the anaerobic tank of Shaoxing III.

Figure 2.

Bacterial community composition at phylum (A) and genus level (B).

At a genus level (see Supplementary Material S2 and Fig. 2B), the sample from Xiangyang harbored mainly Methylotenera and uncultured Methylophilaceae. The most abundant genus in Qige was an unknown genera, representing 27%, followed by Nitrospira and Caldilineaceae_uncultured which accounted for 10.23% and 6.8% respectively. Compared to the samples from the WWTPs that mainly treat domestic sewage, the most abundant microbe in the samples from Shaoxing and Shangyu was Thauera (ranging from 11.3% to 38.3%). The two samples from the oxidation ditch of the Shaoxing 2nd and 3rd project had the most Thauera, (accounting for 32.8% and 38.36% respectively). Sample SY-A had a similar microbial composition with SY-O, with the main constituents being Thauera, Thiobacillus and Parvularcula. SX-3-A mostly contained Thauera, Macellibacteroides, Dechloromonas, Desulfuromonas and Arcobacter. Similarly to SX-3-A, microbes related to desulfuration were also represented in SX-1-A. In SX-1-O, SX-2-O and SX-3-O, Xanthomonadales was the third largest constituent after Thauera and unclassified genera (others).

ß diversity (between-habitat diversity)

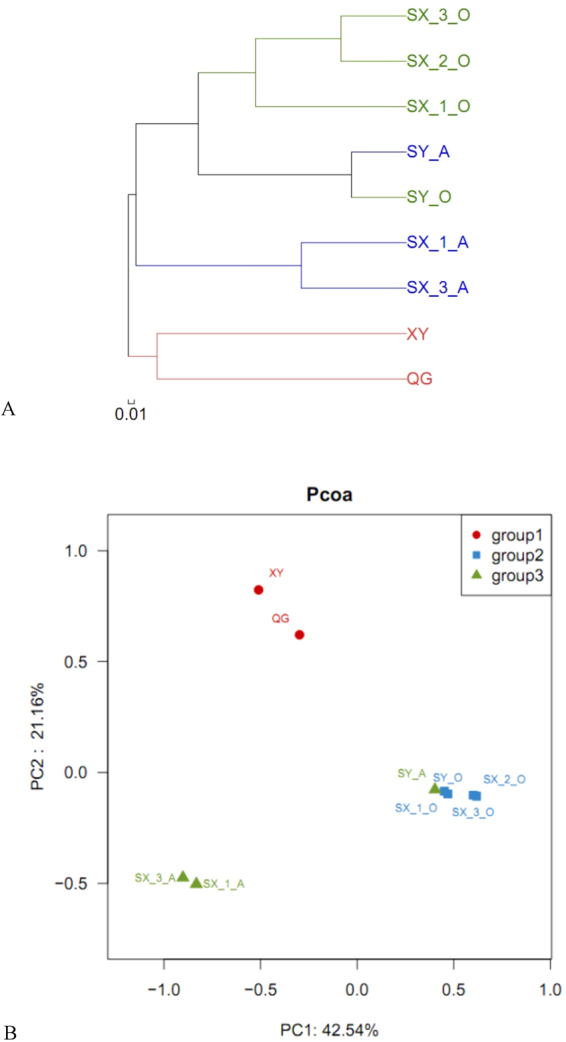

The ß diversity reflects the similarity of the microbial community compositions of the sludge samples. The similarity of the 9 sludge samples was evaluated using two independent methods: correspondence analysis (CA) and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). CA is based on abundances of OTUs and PCoA is based on weighted UniFrac distances19. These methods reveal the similarities of different active sludge samples.

According the linkage of OTUs (CA analysis, Fig. 3A), the bacterial communities in the 9 samples were clustered into 4 large groups: Group I contained all the activated sludge samples from the aeration tank of Shaoxing; Group II contained the two samples from Shangyu; Group III was the sludge from the anaerobic tank of Shaoxing 1st, and 3rd project, which share the same influent; Group IV consisted of the sludge from the two WWTPs that mainly treat domestic sewage and use A2O processes (Qige and Xiangyang).

Figure 3.

Similarity analysis of the 9 sludge samples. (A) Based on CA cluster analysis, according to Bray Curtis distance (the average linkage); (B) Based on PCoA (Principle co-ordinates analysis). Every dot represent a sample plotted according to their OUT composition and abundance(stress value = 0.12), a positive correlation between the distance of two dot and their similarity. Cluster the 9 samples into 3 groups. Group I contains SX-1-O, SX-2-O, SX-3-O, SY-A, SY-O; Group II contains SX-1-A, SX-3-A; Group III contains QG and XY.

According to weighted UniFrac distances (PCoA analysis, Fig. 3B), significant position differences occurred between the sludge samples from the ordinary municipal wastewater treatment systems (Qige and Xiangyang), the anaerobic tank of industrial wastewater treatment system (SX-1-A, SX-3-A) and the other industrial wastewater treatment systems (SX-1-O, SX-2-O, SX-3-O, SY-A, SY-O). For PC1 dimensionality, the samples from the municipal wastewater treatment systems were located between −0.51 and −0.3; samples from the anaerobic tank sample of industrial wastewater treatment system were located between −0.902 and −0.832; and the other samples of industrial wastewater treatment systems were located between 0.4 and 0.62. For PC2 dimensionality, the samples from municipal wastewater treatment systems were located between 0.62 and 0.823; the anaerobic tank samples of industrial wastewater treatment system were located between −0.503 and −0.474; and the other samples of industrial wastewater treatment systems were located between −0.107 and −0.078. The exact positions on PC1, PC2 and PC3 dimensionality can be found in Supplementary Material 3.

Core genera identification

Core bacterial phylotypes were defined as OUT when they constituted greater than 3% of the total number of sequence reads for each sample. There were no common core genera detected in all the samples, this can be inferred by functional redundancy. In other words, if some of the core genera could be replaced by other genera that have the same functional role in active sludge, that genera may not need to be presented in all active sludge. For instance, although high concentrations of Thauera were found in all 7 samples from industrial wastewater treatment plants (Shao-xing and Shang-yu) Thauera had a low concentration in the domestic sewage treatment system (Xiangyang and QiGe WWTPs). Macellibacteroides and Desulfuromonas were mostly found in the anaerobic tank of Shaoxing, where Xanthomonadales was abundant in their aeration tank. Thus, in this study, core genera were discussed respectively according to the aforementioned group categories.

The core genera of the sample from three aeration units of Shaoxing (Group I) were Thauera and Xanthomonadales. The core genera of the two samples from Shangyu (Group II) were Thauera, Thiobacillus and Nitrospira. In the anaerobic units of Shaoxing (Group III), the core genera were Desulfuromonas and Thauera. Noticeably, although the cluster relationship between Xiangyang and QiGe WWTPs is closely clustered in Group IV, their population structure was quite different at the genera level. The core genera of QiGe WWTP were Nitrospira, Caldilineaceae, Defluviicoccus and Anaerolineaceae. The core genera of XiangYang WWTP were Methylotenera (within family Methylophilaceae), uncultured Methylophilaceae, Saprospiraceae, Chitinophagaceae. The distribution of core phylotypes in every sample is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The core genera distribution.

| sample code | SX-1-A | SX-3-A | SX-1-O | SX-2-O | SX-3-O | SY-A | SY-O | QG | XY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| core genus (percentage) | Thauera (11.34%) | Thauera (16.22%) | Thauera (27.32%) | Thauera (32.86%) | Thauera (38.36%) | Thauera (15.67%) | Thauera (21.17%) | Nitrospira (10.23%) | Methylotenera (19.2%) |

| Desulfomicrobium (11.11%) | Macellibacteroides (11.25%) | Xanthomonadales_norank (10.16%) | Xanthomonadales_norank (5.56%) | Xanthomonadales_norank (4.95%) | Sh765B-TzT-29_norank (7.91%) | Thiobacillus (10.57%) | Caldilineaceae_uncultured (6.87%) | Methylophilaceae_uncultured (12.25%) | |

| Synergistaceae_uncultured 9.23%) | Dechloromonas (5.61%) | PHOS-HE36_norank (6.56%) | PHOS-HE51_norank (4.2%) | PHOS-HE51_norank (3.65%) | Parvularcula (7.27%) | Parvularcula (5.97%) | Defluviicoccus (4.77%) | Saprospiraceae_uncultured (4.94%) | |

| Desulfuromonas (7.67%) | Desulfuromonas (5.23%) | Comamonadaceae_unclassified (3.07%) | NS9_marine_group_norank (3.76%) | NS9_marine_group_norank (3.57%) | Thiobacillus (6.44%) | Sh765B-TzT-29_norank (5.62%) | Anaerolineaceae_uncultured (3.09%) | Chitinophagaceae_uncultured (3.85%) | |

| Cytophagaceae_uncultured (6.72%) | Arcobacter (5.23%) | Nitrospira (3.08%) | Nitrospira (3.28%) | TK10_norank (3.03%) | |||||

| Macellibacteroides (6.02%) | Paludibacter (3.97%) | ||||||||

| Clostridiales_uncultured (3.99%) | Synergistaceae_uncultured (3.2%) | ||||||||

| Arcobacter (3.15%) | Geobacter (3.07%) | ||||||||

| Propionivibrio (3.1%) | |||||||||

| Totally | 62.35% | 53.79% | 47.10% | 46.39% | 50.50% | 40.37% | 46.61% | 27.99% | 40.25% |

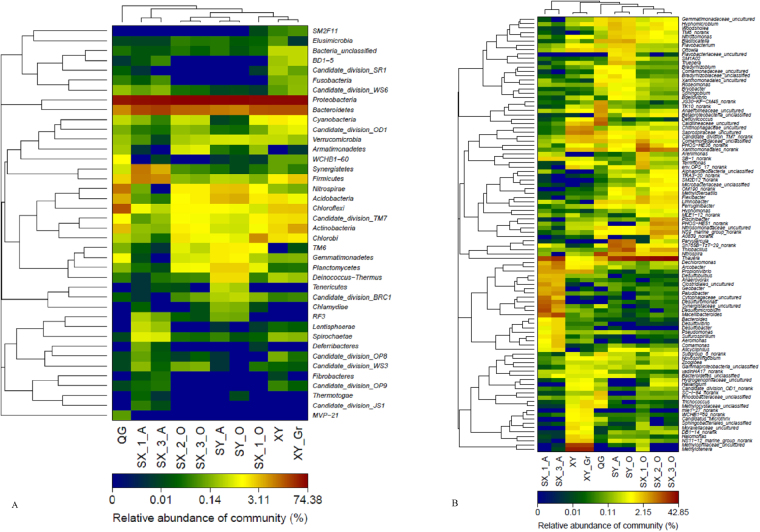

To visualize the differences in the bacterial community structures of the samples, a heat-map with cluster analysis was performed at the phylum and genus level (Fig. 4). Consistent with the PCoA results, the heat-map analysis also revealed the significant effect of influent characteristics on the microbial community biodiversity.

Figure 4.

Heat-map of microbial community composition with cluster analysis. The color intensity in each panel shows the percentage in a sample, referring to color key at the bottom.

Discussion

Previous papers have suggested that the observed read abundance may be affected by the DNA extraction method8,20. In this study, the DNA of the Xiangyang sample was extracted using two different cell disruption methods. In the first, DNA was extracted using a normal commercial isolation kit. In the second the sample it was firstly ground with liquid nitrogen prior to the using of the isolation kit. The results show that the Shannon-index varied according to the DNA extraction method. The sample DNA extracted with the method that included nitrogen grinding had a higher Shannon index (4.83) than of that without (4.68). This indicated that liquid nitrogen grinding could be an effective supplemental protocol for sample DNA preparation to obtain more accurate sequencing data.

Although Shaoxing and Shangyu WWTPs were both deal with dyeing industry wastewater, the GC-MS test results demonstrated that their influent differed considerably. Benzyloxy-benzoic acid, was thought to be specific to that of Shangyu and absent in Shaoxing. The influent organic components of the general domestic wastewater treatment systems (Qige and Xiangyang) was obviously different to the influent components of the industrial ones (Shaoxing and Shangyu), where long chain organic pollutants were rare in the domestic sewage treatment system. Zhou and colleagues suggest that that microbial richness is strongly influenced by the diversity of carbon substrates21. However, in the activated sludge, the taxonomic richness found in the domestic sewage treatment systems was significantly greater than that found in the industrial activated sludge. This might be due to the concentration of volatile fatty acids in influent not being fully reflected by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

In accordance with previous study results22, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Chloroflexi were detected as the dominant phyla regardless of the sample site. Many researchers have reported Proteobacteria as the most dominant phylum in various municipal wastewater treatment plants, representing from 21–53% of the total bacterial effective sequences4,22–25. Compared to previous reports, Proteobacteria occupied higher percentages in the WWTPs of this study. Bacteroidetes and Chloroflexi participate in the degradation of polymers and complex organic substances. These bacteria decompose dead cells and EPS (Exopolysaccharides), which contain polysaccharides and proteins, into simple organic molecules such as ethanol and lactate. These simple molecules can be utilized by other species in their metabolism. These bacteria can be sustained in rigorous environments and can act to refresh bacterial communities26. However, the similarities existed on phylum level, were not reflected on the genus level (Fig. 2). Results of ß diversity analysis (Fig. 3) indicate that the microbial community composition varied with influent type and dissolved oxygen concentration. Whilst Ibarbalz and colleagues indicated that it is the influent characteristics that determine the bacterial community composition24, Wells and colleagues suggested that it is the oxygen concentration that has the main influence27. Given that our studied WWTPs were of very different configuration, process and influent type, we were able conclude that influent type was the most important factor to determine bacterial community structure and that dissolved oxygen concentration was a secondary factor.

Comparing the Xiangyang and Qige samples, although they were both from reflux sludge of a domestic sewage treatment plants with similar A/A/O processes, the dominant genera of XY were from the Methylophilaceae. It has been reported that methanol, and a very limited range of other carbon compounds such as methylated amines, formate, glucose, and fructose, can be utilized as sole carbon and energy sources28. Nitrate and ammonium salts are used as nitrogen sources. No vitamins or other growth factors are required29. Trotsenko reports that the culture of the Methylophilaceae family is appropriate for elimination of methanol from industrial sewage, such as in the case of influent from cellulose sulfate manufacturing facilities30. Methylophilaceae has also been found to be abundant in a unique WWTP (Viborg) in Denmark where additional methanol was added as carbon source for denitrification8. Addition of external carbon sources to post-denitrification systems is frequently used in wastewater treatment plants to enhance nitrate removal31. Therefore, it has been hypothesized that Methylophilaceae is linked with methanol enhanced denitrification in WWTPs. In the Qige WWTP, a well-described nitrite oxidizing bacteria (NOB) - Nitrospira was the most abundant microbe (10.23%). The ability of Nitrospira to perform complete nitrification has also been discovered recently32. Another two highly presented genera- uncultured Caldilineaceae and Anaerolineaceae, have been reported as the PAOs (phosphorus accumulating organisms) in wastewater treatment systems33,34. The potential nitrification and phosphorus accumulation ability of these microbes provides a plausible explanation for the relatively higher removal rate of NH4 +-N and T-P of the Qige WWTP.

In this study, although Thauera was detected in all samples, it was only dominant in the industrial WWTPs (Shaoxing and Shangyu) rather than in the domestic WWTPs (Qige and Xiangyang). This is consistent with the results of several other studies35,36 that the Thauera genus is a functionally important group. The genus Thauera belongs to the family Rhodocyclaceae of Beta-Proteobacteria which has been widely found in WWTPs and has been shown to be a high versatile aromatic compound with high degrading ability in aerobic and denitrification conditions37,38. Under anaerobic conditions, aromatics, such as phenol and cresol, are firstly transformed into a central intermediate benzoyl-CoA by Thauera through various peripheral pathways, and then degraded through the same central benzoyl-CoA pathway39. Therefore, Thauera is considered to be important for all industrial wastewater treatment systems because it plays a key role in refractory aromatic hydrocarbon (e.g. indole and toluene) degradation under denitrification,. A high concentration of textile dying industrial influent would contribute to a wider ecological amplitude for Thauera.

Comparing the aeration tank and anaerobic tanks within the three Shaoxing wastewater treatment systems, sulfate reducing bacteria (Desulfomicrobium) and fermentative bacteria (Macellibacteroides and Clostridiales) were the dominant genera in the anaerobic system. Desulfomicrobium could utilize ethanol as an electron donor and reduce sulfate in the reaction and have commonly been isolated from the oxic/anoxic interlayer of the oligotrophic lake stechlin40. This indicates that these species are particularly adapted to starvation conditions41. Considering the intensity of Desulfomicrobium, we hypothesize that this species may consume residual sulfate and organic substances produced from other bacterial fermentations42,43 such as those of Macellibacteroides and Clostridiales. Fermentative bacteria could hydrolyze proteins into polypeptides and amino acids; hydrolyze lipids into long-chain fatty acid (LCFAs) and glycerol; and hydrolyze polycarbohydrates into sugars and alcohols. Fermentative bacteria then convert the intermediates into volatile fatty acids, hydrogen and carbon dioxide44. Concurrently, some major species (such as Xanthomonadales) decrease in aeration tanks, owing to the presence of ammonia and sulfide as other by-products of organic fermentation. Thus, it could be speculated that within sewage treatment plants that treat dye industry wastewater containing aromatic hydrocarbons, the core genera of their anaerobic system would likely consist of aromatic hydrocarbon degrading bacteria, primarily Thauera sp, fermentative bacteria, such as Macellibacteroides, and sulfate reducing bacteria, such as Desulfomicrobium. Thauera destroys aromatic organics under anaerobic conditions. Fermentative bacteria then turn the organic pieces into volatile fatty acids, which are used as electronic donors for biological desulphurization. In the actual operation of dyeing wastewater treatment processes, the bioactivity and quantity of Thauera and fermentative bacterial should be considered relating to high nitrogen removal and organic pollutant degradation performance.

Many synthetic sulphonated aromatic compounds are used as primary materials to produce dyes and many of these are released as by-products in the effluents of the textile dyeing industry17. In addition, Na2SO4 is a widely-used textile dyeing auxiliary and sulfuric acid is also used to regulate the pH within wastewater treatment process of textile dyeing industry. Therefore, sulphate reducing bacteria like Desulfomicrobium, Desulfuromonas, Desulfovibrio, Sulfurospirillum, Desulfobacter and Thiobacillus were found in industrial wastewater treatment system of this study. Among these, Thiobacillus is an an autotrophic facultative anaerobic bacteria, known for its ability to couple denitrification to inorganic sulfur-compound oxidation45. In the Shangyu WWTP, in addition to the previously mentioned Thauera, 10% of the microbe samples in the aeration tank and 6% in the anaerobic tank consisted of Thiobacillus where the presence of synthetic dye and other dyeing auxiliary effluent components seems to create an ideal growth environment for them.

In summary, nitrogen grinding is an effective pretreatment protocol in sample DNA preparation, to obtain more accurate sequencing data. The microbiological compositions of activated sludge were greatly influenced by the influent composition and level of dissolved oxygen. Additionaly, the sludge from domestic sewage treatment plants formed different clusters to that of those from the sludge of industrial wastewater treatment. It could be inferred that Nitrospira, Caldilineaceae and Anaerolineaceae were highly related to domestic wastewater treatment systems and perform roles of nitrogen and phosphorus removal, whereas Thauera remained highly related to all the industrial wastewater treatment systems. Thauera, Macellibacteroides and Desulfomicrobium worked together in the WWTPs that process a high proportion of textile dye wastewater. Thauera and Thiobacillus were key functional microbes relating to fine chemical wastewater treatment systems. Good control of these functional species will be of great significance for WWTP process management.

Methods

Sample collection

Prior to the date of sampling, the WWTPs were operated under stable conditions. The air temperature fluctuations upon the days of sampling ranged from 6–18 °C. A volume of 200 mL wastewater containing suspended biomass was collected from the municipal WWTPs of Shaoxing city, Shangyu city, Hangzhou city and Xiangyang city. The characteristics of all these WWTPs are listed in Table 1. The samples were stored on ice. Biomass was collected by centrifugation of the samples at 4,000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature. Samples were then stored at −80 °C for further molecular biological analysis.

Influent quality analysis of WWTPs

The features of the WWTPs were provided by the WWTP personnel. Chemical oxygen demand and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5), total Kjeldhal nitrogen (T-N), ammonia (NH4 + -N) and total phosphorus (T-P) were determined by standard analytical procedures46.

In accordance with the sampling and analytic steps of the EPA47, organic pollutants were extracted from the samples as follows: 500 ml wastewater was adjusted to neutral pH, and then extracted with 50 ml of dichloromethane (DCM). The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min, twice. The extractions were then combined and the raffinate was adjusted to pH 12 using 5 mol/L NaOH, and then extracted twice with 25 mL DCM. The extractions were combined again, the raffinate adjusted to pH 2 with 20% sulfuric acid, and then extracted twice with 25 mL DCM. Finally, all the three extractions were combined and evaporated to dry under nitrogen flow and immediately dissolved in 200 μL DCM for injection onto GC-MS.

GC-MS analysis

The samples were analyzed using an Angilent 7890 A GC combined with a 5975 C mass selective detector (MSD) with an HP-5 silica capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The oven temperature was increased from 70 °C to 270 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. Helium was used as the carrier gas with a constant flow mode of 1.2 ml/min. The injector, ion source and interface temperatures were 250 °C, 230 °C and 240 °C respectively. The split ratio was 100:1. Samples (1 μl) were injected. The MSD was operated in EI mode at 70 ev and the full scan data was collected at a scan rate of 2.6 scans/s and 1200 EMV. The quantitative GC-MS data of major organic pollutants from waste-water were based on base peak abundances as obtained from total ion current (TIC) analysis. The identification of compounds was based on retention times, GC-MS library comparisons and published data. Chromatographic data was collected and evaluated using ChemStation software (Agilent).

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and Illumina sequencing

Total DNA extraction was performed in duplicate for each sample using a DNA Isolation Kit (E.Z.N.A., Omega, Norcross, Georgia, U.S.) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The sample from Xiang-yang was simultaneously processed using a liquid nitrogen grinding method to be used as a reference (see Supplementary Material 4). The purity and quantity of extracted DNA were determined by UV spectrophotometry at 260 and 280 nm. DNA extracts were stored at −20 °C. Bacterial 16 S rRNA gene fragments were PCR-amplified with primers 338 F (5′-CCTACGGGNBGCASCAG -3′) and 806 R (5′-GGACTACNVGGGTATCTAAT-3′). The primer set amplifies fragments corresponding to the V3-V4 hypervariable regions of the 16 S rRNA and each barcode represents an eight-base sequence unique to each sample. PCR reactions were performed in triplicate upon 20 μL of mixture containing 4 μL 5 × FastPfu buffer. All PCR amplifications were performed using an ABI GeneAmp® 9700 thermocycler. Each of the PCR reactions were performed in triplicate upon 20 μL of mixture containing 4 μL of 5 × FastPfu Buffer, 2 μL of 2.5 mM dNTPs, and 0.8 μL of each primer (5 μM). Amplicons were extracted from 2% agarose gels and purified using an AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, U.S.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then quantified using QuantiFluor™ -ST (Promega, U.S.). Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts and paired-end sequencing (2 × 250) was conducted on an Illumina MiSeq platform according to standard protocols.

Post run analysis

Raw fastq files were demultiplexed and quality-filtered using QIIME (version 1.17) with the following criteria: (i) The 250 bp reads were truncated at any site receiving an average quality score of <20 over a 10 bp sliding window. Truncated reads that were shorter than 50 bp were discarded; (ii) Any cases of exact barcode matching, 2 nucleotide mismatch in primer matching, and reads containing ambiguous characters, were all removed. (iii) Only sequences with segments that overlaped for more than 10 bp were assembled according to their overlap sequence. Reads which could not be assembled were discarded48.

Operational Units (OTUs) were clustered with 97% similarity cutoff using UPARSE (version 7.1 http://drive5.com/uparse/). Chimeric sequences were identified and removed using UCHIME. The phylogenetic affiliation of each 16 S rRNA gene sequence was analyzed by RDP Classifier using a confidence threshold of 70%49.

Correspondence analysis (CA) grouped the bacterial communities of different activated sludge samples on the basis of (1) taxonomy results obtained using the RDP Classifier (excluding those unclassified sequences), and (2) operational taxonomic units (OTUs) generated using RDP Complete Linkage Clustering from the merged pool of sequences of all the sludge samples50.

Availability of data and materials

The data is included within the manuscript, and all data is fully available without restriction.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Accession number(s)

The sequences were deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive under accession numbers: SRP110572 (SRS2316506- SRS2316515).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Lizong Zhu of Zhejiang University, Mr Dan Yu, Huang Cheng Hua and manager Pan Wei long for sludge samples. This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 51478416 and 51008269], Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province [No. LY13E080003], Public Projects of Zhejiang Province [No. 2014C33017], and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Author Contributions

Xiangyang Xu conceived the project. Bo Zhang wrote the main manuscript text. Liang Zhu revised the manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-17743-x.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yang C, et al. Phylogenetic Diversity and Metabolic Potential of Activated Sludge Microbial Communities in Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment Plants. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:7408–7415. doi: 10.1021/es2010545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang YH, et al. Nitrogen removal and microbial characteristics in CANON biofilters fed with different ammonia levels. Bioresour Technol. 2014;171:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sogin ML, et al. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored “rare biosphere”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12115–12120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605127103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang T, Shao MF, Ye L. 454 Pyrosequencing reveals bacterial diversity of activated sludge from 14 sewage treatment plants. ISME J. 2012;6:1137–1147. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SH, et al. Monitoring bacterial community structure and variability in time scale in full-scale anaerobic digesters. J Environ Monit. 2012;14:1893–1905. doi: 10.1039/c2em10958a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werner JJ, et al. Bacterial community structures are unique and resilient in full-scale bioenergy systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4158–4163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015676108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye L, Zhang T, Wang TT, Fang ZW. Microbial structures, functions, and metabolic pathways in wastewater treatment bioreactors revealed using high-throughput sequencing. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:13244–13252. doi: 10.1021/es303454k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saunders AM, Albertsen M, Vollertsen J, Nielsen PH. The activated sludge ecosystem contains a core community of abundant organisms. ISME J. 2016;10:11–20. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu D, Liu ST, Chen Q, Ni JR. Microbial community compositions in different functional zones of Carrousel oxidation ditch system for domestic wastewater treatment. AMB Express. 2017;7:13. doi: 10.1186/s13568-016-0310-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YS, et al. Performance of a full-scale modified anaerobic/anoxic/oxic process: High-throughput sequence analysis of its microbial structures and their community functions. Bioresour Technol. 2016;220:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shchegolkova NM, et al. Microbial Community Structure of Activated Sludge in Treatment Plants with Different Wastewater Compositions. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu M, Wang XH, Wen XH, Xia Y. Microbial community structures in different wastewater treatment plants as revealed by 454-pyrosequencing analysis. Bioresour Technol. 2012;117:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner M, Loy A. Bacterial community composition and function in sewage treatment systems. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2002;13:218–227. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(02)00315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albertsen M, Hansen LBS, Saunders AM, Nielsen PH, Nielsen KL. A metagenome of a full-scale microbial community carrying out enhanced biological phosphorus removal. ISME J. 2012;6:1094–1106. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding XC, et al. The total and functional bacterial community of nitrogen removal in the SND ditches. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2017;118:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2016.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wada A, et al. Rapid Discrimination of Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria in Liquid Samples by Using NaOH-Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Solution and Flow Cytometry. PLoS One. 2012;7:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwitzguebel JP, Aubert S, Grosse W, Laturnus F. Sulphonated aromatic pollutants - Limits of microbial degradability and potential of phytoremediation. Environ Sci Poll R. 2002;9:62–72. doi: 10.1007/BF02987317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogleni N, Ovez S, Ogleni O. Wastewater characterization and microbial diversity of a textile industry wastewater treatment system. Fresenius Environ Bull. 2010;19:1911–1916. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lozupone C, Hamady M, Knight R. UniFrac - An online tool for comparing microbial community diversity in a phylogenetic context. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielsen PH, et al. A conceptual ecosystem model of microbial communities in enhanced biological phosphorus removal plants. Water Res. 2010;44:5070–5088. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou JZ, et al. Spatial and resource factors influencing high microbial diversity in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:326–334. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.1.326-334.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cydzik-Kwiatkowska A, Zielinska M. Bacterial communities in full-scale wastewater treatment systems. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;32:8. doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ariesyady HD, Ito T, Okabe S. Functional bacterial and archaeal community structures of major trophic groups in a full-scale anaerobic sludge digester. Water Res. 2007;41:1554–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2006.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibarbalz FM, Figuerola ELM, Erijman L. Industrial activated sludge exhibit unique bacterial community composition at high taxonomic ranks. Water Res. 2013;47:3854–3864. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Q, et al. Bacterial community compositions of coking wastewater treatment plants in steel industry revealed by Illumina high-throughput sequencing. Bioresour Technol. 2015;179:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang K, Cao XL, Sheng YX, Cao HB. Spatial distribution of bacterial community in EGSB reactor treating synthetic sulfate-containing wastewater at low organic loading rate. Chin Sci Bull. 2014;59:54–61. doi: 10.1007/s11434-013-0043-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells GF, Park HD, Eggleston B, Francis CA, Criddle CS. Fine-scale bacterial community dynamics and the taxa-time relationship within a full-scale activated sludge bioreactor. Water Res. 2011;45:5476–5488. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eyice O, et al. SIP metagenomics identifies uncultivated Methylophilaceae as dimethylsulphide degrading bacteria in soil and lake sediment. ISME J. 2015;9:2336–2348. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rissanen AJ, Ojala A, Fred T, Toivonen J, Tiirola M. Methylophilaceae and Hyphomicrobium as target taxonomic groups in monitoring the function of methanol-fed denitrification biofilters in municipal wastewater treatment plants. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;44:35–47. doi: 10.1007/s10295-016-1860-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trotsenko YA, Doronina NV, Khmelenina VN. Biotechnological potential of aerobic methylotrophic bacteria: A review of current state and future prospects. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2005;41:433–441. doi: 10.1007/s10438-005-0078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torresi E, et al. Impact of external carbon dose on the removal of micropollutants using methanol and ethanol in post-denitrifying Moving Bed Biofilm Reactors. Water Res. 2017;108:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daims, H. et al. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature528, 504- + (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Kindaichi T, Nierychlo M, Kragelund C, Nielsen JL, Nielsen PH. High and stable substrate specificities of microorganisms in enhanced biological phosphorus removal plants. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:1821–1831. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bond PL, Hugenholtz P, Keller J, Blackall LL. Bacterial community structures of phosphate-removing and non-phosphate-removing activated sludges from sequencing batch reactors. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1910–1916. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1910-1916.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomsen TR, Kong Y, Nielsen PH. Ecophysiology of abundant denitrifying bacteria in activated sludge. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;60:370–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao YJ, Zhang XJ, Xia X, Zhong HH, Zhao LP. Versatile aromatic compound-degrading capacity and microdiversity of Thauera strains isolated from a coking wastewater treatment bioreactor. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;37:927–934. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foss S, Harder J. Thauera linaloolentis sp. nov. and Thauera terpenica sp. nov., isolated on oxygen-containing monoterpenes (linalool, menthol, and eucalyptol) and nitrate. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1998;21:365–373. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(98)80046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shinoda Y, et al. Aerobic and anaerobic toluene degradation by a newly isolated denitrifying bacterium, Thauera sp strain DNT-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:1385–1392. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1385-1392.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harwood CS, Burchhardt G, Herrmann H, Fuchs G. Anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds via the benzoyl-CoA pathway. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1998;22:439–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00380.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sass H, Cypionka H, Babenzien HD. Vertical distribution of sulfate-reducing bacteria at the oxic-anoxic interface in sediments of the oligotrophic Lake Stechlin. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;22:245–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1997.tb00377.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bade K, Manz W, Szewzyk U. Behavior of sulfate reducing bacteria under oligotrophic conditions and oxygen stress in particle-free systems related to drinking water. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2000;32:215–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2000.tb00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jabari L, et al. Desulfotomaculum peckii sp nov., a moderately thermophilic member of the genus Desulfotomaculum, isolated from an upflow anaerobic filter treating abattoir wastewaters. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:2082–2087. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.043893-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jabari L, et al. Macellibacteroides fermentans gen. nov., sp nov., a member of the family Porphyromonadaceae isolated from an upflow anaerobic filter treating abattoir wastewaters. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:2522–2527. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.032508-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salminen E, Rintala J. Anaerobic digestion of organic solid poultry slaughterhouse waste - a review. Bioresour Technol. 2002;83:13–26. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(01)00199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beller HR, et al. The genome sequence of the obligately chemolithoautotrophic, facultatively anaerobic bacterium Thiobacillus denitfificans. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:1473–1488. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.4.1473-1488.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.China, S. E. P. A. o. (Chinese Environmental Science Press, Beijing, 2002).

- 47.Castillo M, Barcelo D. Characterisation of organic pollutants in textile wastewaters and landfill leachate by using toxicity-based fractionation methods followed by liquid and gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometric detection. Anal Chim Acta. 2001;426:253–264. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)00828-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amato KR, et al. Habitat degradation impacts black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) gastrointestinal microbiomes. ISME J. 2013;7:1344–1353. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLellan SL, Huse SM, Mueller-Spitz SR, Andreishcheva EN, Sogin ML. Diversity and population structure of sewage-derived microorganisms in wastewater treatment plant influent (vol 12, pg 378, 2010) Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:1376–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data is included within the manuscript, and all data is fully available without restriction.