Abstract

The GSTT1 and GSTM1 genes are key molecules in cellular detoxification. Null variants in these genes are associated with increase susceptibility to developing different types of cancers. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes in Mestizo and Amerindian individuals from the Northwestern region of Mexico, and to compare them with those reported worldwide. GSTT1 and GSTM1 null variants were genotyped by multiplex PCR in 211 Mestizos and 211 Amerindian individuals. Studies reporting on frequency of GSTT1 and GSTM1 null variants worldwide were identified by a PubMed search and their geographic distribution were analyzed. We found no significant differences in the frequency of the null genotype for GSTT1 and GSM1 genes between Mestizo and Amerindian individuals. Worldwide frequencies of the GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes ranges from 0.10 to 0.51, and from 0.11 to 0.67, respectively. Interestingly, in most countries the frequency of the GSTT1 null genotype is common or frequent (76%), whereas the frequency of the GSMT1 null genotype is very frequent or extremely frequent (86%). Thus, ethnic-dependent differences in the prevalence of GSTT1 and GSTM1 null variants may influence the effect of environmental carcinogens in cancer risk.

Keywords: Oxidative stress, GSTT1, GSTM1, null variants

Introduction

The family of the glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) is composed of enzymes that play an essential role in the cellular protection against a wide range of hazardous molecules, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), xenobiotics and electrophilic compounds. The mammalian GSTs can be classified into three groups: cytosolic, mitochondrial and membrane-associated proteins in eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism (MAPEG). Cytoplasmic enzymes are further subdivided into seven groups: Alpha (GSTA), Mu (GSTM), Omega (GSTO), Pi (GSTP), Sigma (GSTS), Theta (GSTT), and Zeta (GSTZ) (Tew and Townsend, 2012). Since the individual GSTs proteins can share ligands, functional redundancy is a common event in the GST-mediated biotransformation of toxic compounds (Luo et al., 2011).

GSTs catalyze the conjugation of reduced glutathione (GSH), the major antioxidant molecule in the cell, to a myriad of hazardous molecules, including carcinogens, drugs and xenobiotics. GSH-conjugated substrates are then transported out of the cell mainly via the ABC (ATP-binding cassette) efflux pumps. Additionally, GSTs are able to detoxify noxious products of the cellular metabolism, such as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species through their glutathione peroxidase activity (Board and Menon, 2013; Galal et al., 2015). These enzymes are involved in cellular processes others than detoxification, including chaperone activities, regulation of kinase-mediated signal transduction and S-glutathionylation cycle (Pajaud et al., 2012; Klaus et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014a).

Early studies highlight the presence of deletion variants (null variants) in the GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes, which are located at chromosomal positions 1p13.3 and 22q11.23, respectively. Individuals with the homozygous genotype for the deletion variants (null/null) in GSTM1 or GSTT1 genes showed the total loss of enzymatic activity of the respective protein (Pemble et al., 1994; Xu et al., 1998). In accordance with their detoxification properties, the deficiency of GSTM1 and GSTT1, either individually or in combination, greatly increases the susceptibility of developing cancer in different organs, including liver, lung and colon (Csejtei et al., 2008; Sui et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014b).

The prevalence of GSTM1 and GSTT1 null alleles shows strong variation among different ethnic groups. For instance, the frequency of the GSTM1 null allele was as low as 0.23 in South Africa, but up to 0.42 in Spain and 0.67 in Singapore (Masimirembwa et al., 1998; Chan et al., 2011; Ruano-Ravina et al., 2014). With regard to GSTT1, the frequency of the null genotype among Greek individuals was 0.10, whereas in England and Japan the frequency was 0.21 and 0.50, respectively (Garte et al., 2001; Dialyna et al., 2003; Hishida et al., 2005). These differences could modulate the risk to different types of tumors in populations of different ethnic ancestry. For instance, Japan, one of the countries with the highest frequency of the null genotype for both GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes, has a high incidence of colorectal, stomach, esophagus and prostate cancer (WHO, 2012). Although studies about the distribution of GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotypes in a Mexican-Mestizo population have been performed previously (Pérez-Morales et al., 2008; Pérez-Morales et al., 2011; Sánchez-Guerra et al., 2012; Gutiérrez-Amavizca et al., 2013; Sandoval-Carrillo et al., 2014; García-González et al., 2015; Jaramillo-Rangel et al., 2015) no reports of the prevalence of these variants in Mexican Amerindian individuals are available. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine and compare the frequencies of GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotypes in Mexican-mestizo and Amerindian individuals (Tarahumara) from the Northwestern part of the country (State of Chihuahua) with those previously found in other regions of Mexico and around the world.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The sample population was composed of 422 unrelated individuals from the State of Chihuahua, in the Northwest of Mexico: 211 subjects from the Amerindian ethnic group (Tarahumara) and 211 Mexican-mestizo persons. The Tarahumara sample consisted of 138 females and 73 males with ages ranging from seven to 18 years, whereas the Mexican-mestizo group was composed of 88 females and 123 males, with ages ranging from 16 to 30 years. Samples were collect from July 2009 to March 2014. The Tarahumara group consisted of individuals self-recognized as Amerindians, whose two parents and four grandparents were all born in the locality and speak the Tarahumara language. All participants signed a written informed consent, and in the case of underage individuals, the parents signed their informed consent. Local committees of research ethics approved the study following the Declaration of Helsinki.

GSTM1 and GSTT1 genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from 300 μL of whole blood samples using the MasterPure DNA Purification kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA integrity was verified by electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel and DNA concentration was evaluated in a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Genotyping of null variants in the GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes (GenBank accession number: AP000351 and X68676, respectively) was performed by multiplex PCR, as previously described (Arand et al., 1996). Briefly, we used primers to amplify a fragment of the genes GSTM1 (215 bp), GSTT1 (480 bp) and the housekeeping GAPDH (315 bp), as an internal amplification control, for each sample using a conventional PCR protocol. Also, we used DNA samples with known genotype for GSTM1 and GSTT1 null alleles (GST-T1/M1: wt/wt, wt/null, null/wt and null/null) as positive controls.

The primers used for PCR amplification were:

GSTT1

Forward: 5-TTC CTT ACT GGT CCT CAC ATC TC-3

Reverse: 5-TCA CCG GAT CAT G GC CAG CA-3

GSTM1

Forward: 5-GAA CTC CCT GAA AAG CTA AAG C-3

Reverse: 5-GTT GGG CTC AAA TAT ACG GTG G-3

GAPDH

Forward: 5-GGA TGA CCT TGC CCA CAG CCT-3

Reverse: 5′-CAT CTC TGC CCC CTC TGC TGA-3′

DNA amplification was carried out with an initial denaturing step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The PCR reactions were performed in a Veriti 96-well thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 2.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and visualized by ultraviolet light. In addition, 10% of the samples were genotyped twice from the original DNA sample with a 100% concordance.

Literature search for genotype data

To identify studies reporting on frequencies of GSTM1 and GSTT1 null variants worldwide, a PubMed search was conducted. After excluding meta-analyses and review articles, we considered in our study a total of 57 reports. In order to avoid a bias imposed by the frequency of a gene variant in association with a disease, the frequencies of the null and wild-type genotypes of GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes were extracted only from the healthy population reported in each manuscript, but the respective frequencies in the disease-affected population was not considered.

Statistical analysis

GSTM1 and GSTT1 null and wild-type genotypes in Mestizo and Tarahumara populations were reported as frequency. Our findings were compared with those found in other ethnic groups worldwide. The frequencies of the GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotypes were used to generate maps with their geographic distribution using the QGIS 2.4.0-Chugiak shape file (www.naturalearthdata.com). Statistical analysis was performed using the Fisher’s exact test, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

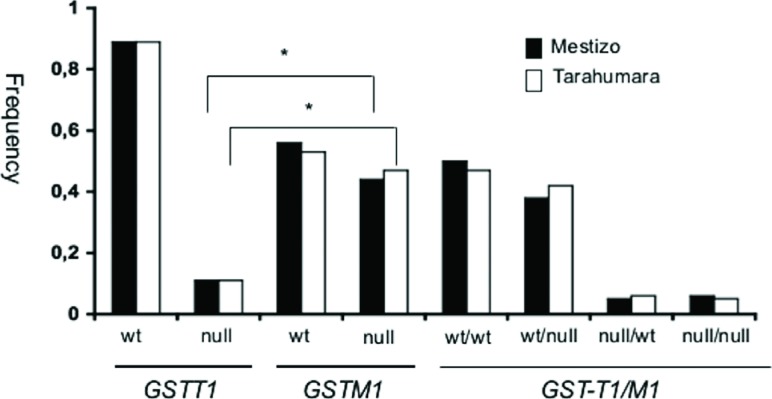

After genotyping the GSTM1 and GSTT1 null polymorphisms, we observed that the GSTM1 null genotype showed a significantly higher frequency than the GSTT1 null genotype in both the Mestizo (0.44 vs. 0.11) and Tarahumara groups (0.47 vs. 0.11). The most common compound genotype in both groups was GST-T1/M1 wt/wt (Mestizo=0.50; Tarahumara=0.47), followed by the GST-T1/M1 wt/null genotype (Mestizo=0.38; Tarahumara=0.42). The compound genotypes with lower frequency in both groups were GST-T1/M1 null/wt (Mestizo=0.05; Tarahumara=0.06) and GST-T1/M1 null/null (Mestizo=0.06; Tarahumara=0.05) (Figure 1). We found no significant difference in the frequencies of the wild type or of null genotype for GSTT1 and GSTM1 between Mestizo and Tarahumara individuals. Likewise, the frequency distribution of the compound genotypes showed no significant difference between Mestizo and Tarahumara individuals.

Figure 1. Frequencies of GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes in Mestizo (black bars) and Tarahumara individuals (white bars) from the northwestern region of Mexico. Wt: wild type. *p < 0.05.

The frequency of the GSTT1 null genotype observed in the Mestizo individuals included in our study was similar to those previously reported in Mexican-Mestizos from the northeastern and central regions of the country (0.11 vs. 0.10–0.13 and 0.12–0.15, respectively), as well as in one population from the Southeast (0.11 vs. 0.09). However, it was significantly higher in comparison with those reported in the western region (0.11 vs. 0.03) (Table 1). In the case of GSTM1, the frequencies of the null genotype found previously in Mexican-Mestizos from the northeastern and western regions were similar to those of our study (0.44 vs. 0.44–0.48, and 0.43, respectively), but populations from the central and southeastern regions showed a significantly lower frequency (0.44 vs. 0.33–0.37, and 0.31, respectively) (Table 1). It is worth mentioning that a Mexican-Mestizo population located in the coastal zone of the southeastern region showed the highest frequency of the null genotype for GSTT1 and the lowest for GSTM1 in our country (0.17 and 0.22, respectively). These data show a clear reduction in the frequency of the GSTM1 null genotype from North to South, whereas in the case of the GSTT1 null genotype no apparent tendency was observed.

Table 1. Frequencies of GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes in different regions of Mexico.

| Region | n | GSTT1 | GSTM1 | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt | null | wt | null | |||

| Northeastern | 118 | 0.87 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 0.48 | Jaramillo-Rangel et al., 2015 |

| Northeastern | 233 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.56 | 0.44 | Sandoval-Carrillo et al., 2014 |

| Northwestern | 211 | 0.89 | 0.11 | 0.56 | 0.44 | This study |

| Western | 125 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.43 | Gutiérrez-Amavizca et al., 2013 |

| Center | 529 | 0.88 | 0.12 | 0.67 | 0.33 | Pérez-Morales et al., 2008 |

| Center | 382 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.63 | 0.37 | Pérez-Morales et al., 2011 |

| Southeastern | 151 | 0.91 | 0.09 | 0.69 | 0.31 | García-González et al., 2015 |

| Southeastern | 82 | 0.83 | 0.17 | 0.78 | 0.22 | Sánchez-Guerra et al., 2012 |

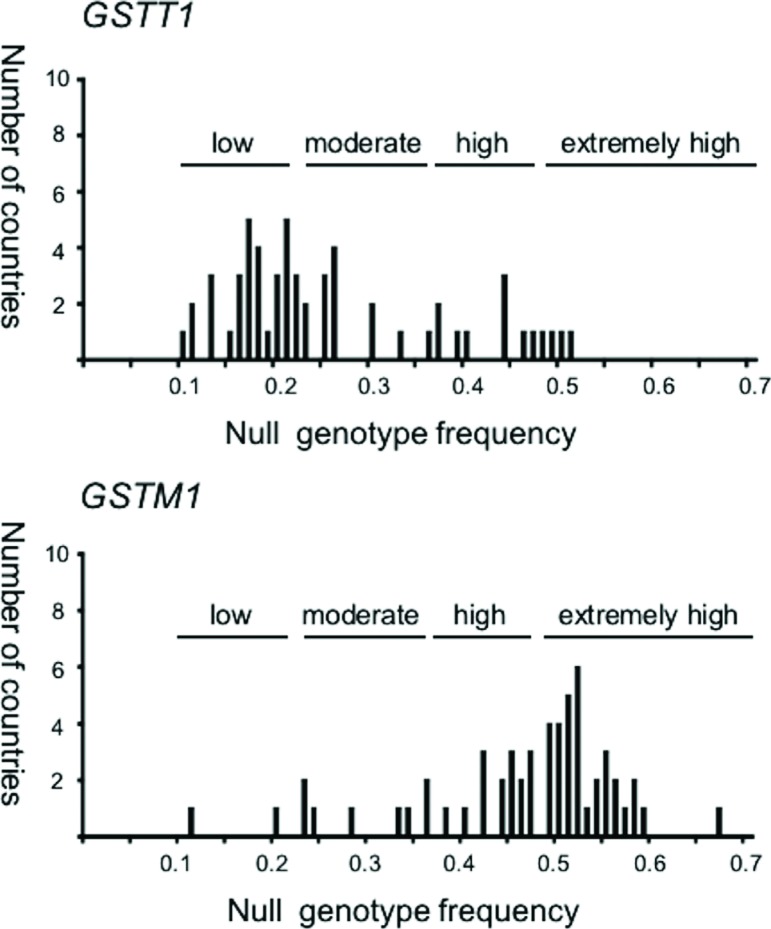

We also collected from the literature the frequencies of the GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes found in 57 countries around the world. The worldwide frequency of the GSTT1 null genotype ranges from 0.10 to 0.51, whereas that of the GSTM1 null genotypes ranges from 0.11 to 0.67 (Table 2). To further compare the prevalence of GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes worldwide, we classified these frequencies in four groups: common (0.10–0.22), frequent (0.23–0.35), very frequent (0.36–0.48), and extremely frequent (more than 0.48). We observed that the reported frequencies for the GSTT1 null genotype were common in 31 countries (55%), frequent in 12 (21%), very frequent in 11 (19%) and extremely frequent only in three (5%) (Figure 2, upper panel). In sharp contrast, the reported frequencies of the GSTM1 null genotype were common in only two countries (3%), frequent in six (10%), very frequent in 17 (30%) and extremely frequent in 32 (56%) (Figure 2, lower panel). Because of the low number of studies reporting frequencies for the compound genotypes, it was not possible make comparisons.

Table 2. Frequencies of GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotype in 57 countries worldwide.

| Continent/Country | Sample size | GSTT1 | GSTM1 | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| America | Argentina | 69 | 0.15 | 0.49 | Fundia et al., 2014 |

| Brazil | 137 | 0.26 | 0.38 | Hatagima et al., 2004 | |

| Canada | 274 | 0.17 | 0.51 | Krajinovic et al., 1999 | |

| Chile | 260 | 0.13 | 0.42 | Acevedo et al., 2014 | |

| Costa Rica | 2042 | 0.20 | 0.51 | Cornelis et al., 2007 | |

| Mexico | 211 | 0.11 | 0.44 | This study | |

| Paraguay | 67 | 0.18 | 0.36 | Gaspar et al., 2002 | |

| USA | 1752 | 0.21 | 0.52 | Gates et al., 2008 | |

| Venezuela | 120 | 0.11 | 0.51 | Chiurillo et al., 2013 | |

| Greenland | 100 | 0.46 | 0.47 | Buchard et al., 2007 | |

| Africa | Cameroon | 126 | 0.47 | 0.28 | Piacentini et al., 2011 |

| Egypt | 200 | 0.30 | 0.55 | Hamdy et al., 2003 | |

| Ethiopia | 153 | 0.37 | 0.44 | Piacentini et al., 2011 | |

| Gambia | 337 | 0.37 | 0.20 | Wild et al., 2000 | |

| Ivory Coast | 133 | 0.33 | 0.36 | Santovito et al., 2010 | |

| Moroco | 60 | 0.22 | 0.45 | Kassogue et al., 2014 | |

| Nambia | 134 | 0.36 | 0.11 | Fujihara et al., 2009 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 513 | 0.25 | 0.55 | Al-Dayel et al., 2008 | |

| Somalia | 100 | 0.44 | 0.40 | Buchard et al., 2007 | |

| South Africa | 96 | 0.20 | 0.23 | Masimirembwa et al., 1998 | |

| Tanzania | 220 | 0.25 | 0.33 | Dandara et al., 2002 | |

| Tunisia | 79 | 0.44 | 0.46 | Ouerhani et al., 2006 | |

| Zimbabwe | 150 | 0.26 | 0.24 | Dandara et al., 2002 | |

| Asia | China | 763 | 0.39 | 0.52 | Liu et al., 2009 |

| India | 251 | 0.16 | 0.34 | Dunna et al., 2013 | |

| Iran | 280 | 0.23 | 0.49 | Rafiee et al., 2010 | |

| Japan | 476 | 0.50 | 0.52 | Hishida et al., 2005 | |

| Korea | 1700 | 0.51 | 0.54 | Kim and Hong, 2012 | |

| Mongolia | 207 | 0.26 | 0.46 | Fujihara et al., 2009 | |

| Philippines | 127 | 0.25 | 0.59 | Baclig et al., 2012 | |

| Singapore | 177 | 0.49 | 0.67 | Chan et al., 2011 | |

| Syria | 172 | 0.17 | 0.23 | Al-Achkar et al., 2014 | |

| Taiwan | 574 | 0.44 | 0.50 | Fujihara et al., 2009 | |

| Thailand | 81 | 0.48 | 0.58 | Klinchid et al., 2009 | |

| Vietnam | 100 | 0.30 | 0.42 | Agusa et al., 2010 | |

| Europe | Bulgaria | 112 | 0.16 | 0.52 | Toncheva et al., 2004 |

| Croatia | 60 | 0.22 | 0.45 | Zuntar et al., 2014 | |

| Czech Rep. | 67 | 0.22 | 0.57 | Binková et al., 2002 | |

| Denmark | 537 | 0.13 | 0.52 | Buchard et al., 2007 | |

| Estonia | 202 | 0.18 | 0.55 | Juronen et al., 2000 | |

| Finland | 482 | 0.13 | 0.47 | Garte et al., 2001 | |

| France | 115 | 0.26 | 0.49 | Abbas et al., 2004 | |

| Germany | 3054 | 0.17 | 0.52 | Kabesch et al., 2004 | |

| Greece | 171 | 0.10 | 0.52 | Dialyna et al., 2003 | |

| Holland | 419 | 0.23 | 0.50 | Garte et al., 2001 | |

| Italy | 546 | 0.17 | 0.49 | Palli et al., 2010 | |

| Lithuania | 456 | 0.16 | 0.47 | Danileviciute et al., 2012 | |

| Poland | 365 | 0.21 | 0.45 | Reszka et al., 2014 | |

| Russia | 352 | 0.19 | 0.50 | Gra et al., 2010 | |

| Serbia | 50 | 0.40 | 0.56 | Stosic et al., 2014 | |

| Slovakia | 332 | 0.18 | 0.51 | Garte et al., 2001 | |

| Slovenia | 386 | 0.21 | 0.50 | Petrovic and Peterlin, 2014 | |

| Spain | 461 | 0.20 | 0.42 | Ruano-Ravina et al., 2014 | |

| Sweden | 203 | 0.18 | 0.51 | Bu et al., 2007 | |

| Turkey | 140 | 0.21 | 0.55 | Aydin-Sayitoglu et al., 2006 | |

| England | 1122 | 0.21 | 0.58 | Garte et al., 2001 | |

| Oceania | Australia | 1246 | 0.17 | 0.54 | Spurdle et al., 2007 |

Figure 2. Frequencies of GSTT1 (upper panel) and GSTM1 (lower panel) null genotypes in 57 countries.

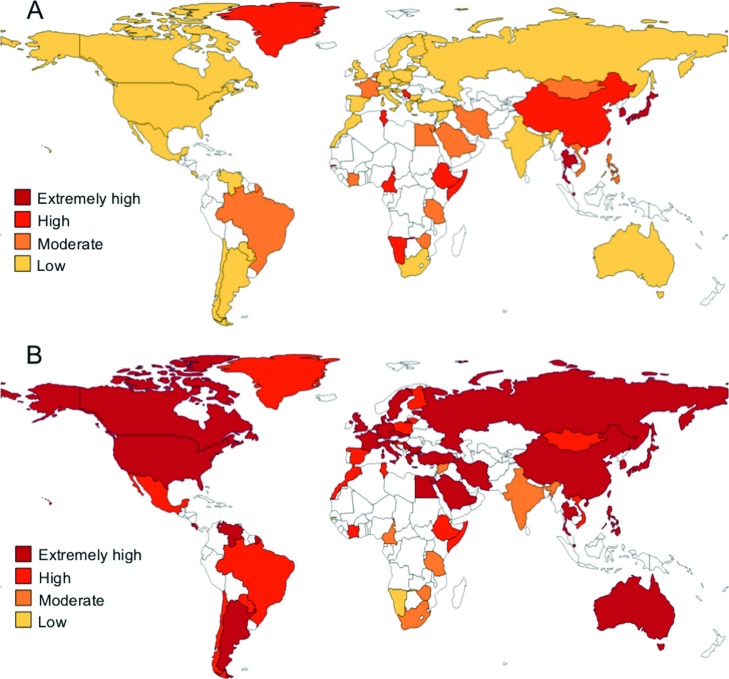

Regarding the geographical distribution of these null variants, the countries where GSTT1 null genotype frequencies were common or frequent were distributed over the five continents, whereas those where the GSTT1 null genotype was very frequent were concentrated mainly in Africa (Namibia, Gambia, Ethiopia, Tunisia, Somalia and Cameroon) and Asia (China, Taiwan and Thailand). It is worth mentioning that the only three countries with extremely frequent presence of this variant were in East Asia (Singapore, Japan and Korea) (Figure 3A). In the case of the GSTM1 null genotype, this variant was common in Namibia and Gambia (Africa), and frequent in Syria and India (Asia), and in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Cameroon and Tanzania (Africa), whereas countries with very frequent and extremely frequent frequency were distributed all over the world (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Distribution of GSTT1 (A) and GSTM1 (B) null genotypes in 57 countries. Low: 0.10–0.22; moderate: 0.23–0.35; high: 0.36–0.48; extremely high: 0.48–0.67.

Discussion

GST proteins are essential molecules in cellular protection against a myriad of environmental and intracellular compounds. Null variants occurring in the GSTT1 and GSTM1 genes are the most common polymorphisms in GST proteins, and their association with various chronic-degenerative diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and different types of cancer including prostate, neck, colorectal, liver and leukemia has been thoroughly studied in different populations (Song et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013; Eslami and Sahebkar, 2014; He et al., 2014; Rao et al., 2014; Masood et al., 2015). Both the prevalence of the GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes as well as their association with disease phenotypes are highly dependent on ethnic background.

The Mexican-Mestizo population is a complex genetic admixture consisting of Amerindian (56%), Caucasian (41%) and African alleles (3%), with a decreasing Caucasian and an increasing Amerindian ancestry from North to South (Lisker et al., 1986).

In our study, we found no significant difference in the frequencies of the GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes among Mexican-Mestizo and Tarahumara individuals from the northwestern region of the country. In addition, we observed a high variability in the frequency of the null genotypes for GSTT1 and GSTM1 among the different geographic regions of the country, ranging from 0.03 to 0.17 for GSTT1 and from 0.22 to 0.48 for GSMT1 (Pérez-Morales et al., 2008, 2011; Sánchez-Guerra et al., 2012; Gutiérrez-Amavizca et al., 2013; Sandoval-Carrillo et al., 2014; García-González et al., 2015; Jaramillo-Rangel et al., 2015). In the case of GSTM1, the frequencies of the null genotypes showed a clear reduction from North to South, whereas the frequency of the GSTT1 null genotypes showed no apparent tendency. The genetic structure of the Mexican population is very complex and is strongly affected by geographical location. For example, populations located in the northern region near to the US border are characterized by an intense admixture with European-derived populations. In contrast, more than 90% of the Amerindian populations in Mexico (68 ethnic groups) are located in the southern region of the country. As the frequency of the GSTM1 null genotype is higher in American populations with European ancestry (e.g., USA and Canada) than in Latino American populations (e.g,. Mexico, Chile and Paraguay), it may be possible that the decreasing frequency from North to South of this variant could be caused by the admixture occurring with Caucasian populations.

Regarding the prevalence of the GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes worldwide, the GSTM1 null genotype was very frequent or extremely frequent (0.36 and above) in the majority of the analyzed countries (86%), whereas the GSTT1 null genotype was common or frequent (from 0.10 to 0.35) in most of the countries (76%). Since the GSTM1 null genotype is more frequent than GSTT1 in every country, this indicates that the loss of function of GSTT1 has a more deleterious effect than GSTM1. However, we cannot discard that other GST proteins could replace GSTM1 but not GSTT1 function.

The lowest frequencies of the GSTT1 null genotype were found in America (0.11–0.20), with exception of Greenland (0.46), followed by Europe (0.10–0.26) and Africa (0.20–0.47); the highest frequencies were in Asia (0.16–0.51). For GSTM1, the lowest frequencies were observed in Africa (0.11–0.55), followed by Asia (0.23–0.67) and America (0.36–0.52); Europe had the highest frequencies (0.42–0.58). Middle East countries showed lower frequencies for both GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes than those from far East Asia (GSTT1: 0.16-0.23 vs. 0.25-0.51; GSTM1: 0.23-0.49 vs. 0.42-0.69). Moreover, countries such as Japan, Korea, Singapore and Thailand showed extremely high frequencies for both the GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes (Table 2). It is worthy of note that the frequency of the GSTM1 null genotype found in a Mexican-Mestizo population from the southeastern region, which has a high African ancestry, was very similar to the frequency found in several African populations, including Cameroon, Gambia, and Zimbabwe (0.22 vs. 0.28, 0.20 and 0.24, respectively) (Wild et al., 2000; Dandara et al., 2002; Piacentini et al., 2011; Sánchez-Guerra et al., 2012).

In summary, the prevalence of the GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes showed a very high diversity, dependent on ethnic background.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the SEP-CONACyT grant number 243587 and PIFIs-UACH 2013-2015.

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Carlos R. Machado

References

- Abbas A, Delvinquiere K, Lechevrel M, Lebailly P, Gauduchon P, Launoy G, Sichel F. GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1 and CYP1A1 genetic polymorphisms and susceptibility to esophageal cancer in a French population: Different pattern of squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3389–3393. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i23.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo CA, Quiñones LA, Catalán J, Cáceres DD, Fullá JA, Roco AM. Impact of CYP1A1, GSTM1, and GSTT1 polymorphisms in overall and specific prostate cancer survival. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agusa T, Iwata H, Fujihara J, Kunito T, Takeshita H, Minh TB, Trang PT, Viet PH, Tanabe S. Genetic polymorphisms in glutathione S-transferase (GST) superfamily and arsenic metabolism in residents of the Red River Delta, Vietnam. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;242:352–362. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Achkar W, Azeiz G, Moassass F, Wafa A. Influence of CYP1A1, GST polymorphisms and susceptibility risk of chronic myeloid leukemia in Syrian population. Med Oncol. 2014;31:889–889. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dayel F, Al-Rasheed M, Ibrahim M, Bu R, Bavi P, Abubaker J, Al-Jomah N, Mohamed GH, Moorji A, Uddin S, et al. Polymorphisms of drug-metabolizing enzymes CYP1A1, GSTT and GSTP contribute to the development of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma risk in the Saudi Arabian population. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:122–129. doi: 10.1080/10428190701704605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arand M, Mühlbauer R, Hengstler J, Jäger E, Fuchs J, Winkler L, Oesch F. A multiplex polymerase chain reaction protocol for the simultaneous analysis of the glutathione S-transferase GSTM1 and GSTT1 polymorphisms. Anal Biochem. 1996;236:184–186. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin-Sayitoglu M, Hatirnaz O, Erensoy N, Ozbek U. Role of CYP2D6, CYP1A1, CYP2E1, GSTT1, and GSTM1 genes in the susceptibility to acute leukemias. Am J Hematol. 2006;81:162–170. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baclig MO, Alvarez MR, Lozada XM, Mapua CA, Lozano-Kühne JP, Dimamay MP, Natividad FF, Gopez-Cervantes J, Matias RR. Association of glutathione S-transferase T1 and M1 genotypes with chronic liver diseases among Filipinos. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2012;3:153–159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binková B, Smerhovsky Z, Strejc P, Boubelík O, Stávková Z, Chvátalová I, Srám RJ. DNA-adducts and atherosclerosis: A study of accidental and sudden death males in the Czech Republic. Mutat Res. 2002;501:115–128. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Board PG, Menon D. Glutathione transferases, regulators of cellular metabolism and physiology. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3267–3288. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu H, Rosdahl I, Holmdahl-Källen K, Sun XF, Zhang H. Significance of glutathione S-transferases M1, T1 and P1 polymorphisms in Swedish melanoma patients. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:859–864. doi: 10.3892/or.17.4.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchard A, Sanchez JJ, Dalhoff K, Morling N. Multiplex PCR detection of GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 gene variants: Simultaneously detecting GSTM1 and GSTT1 gene copy number and the allelic status of the GSTP1 Ile105Val genetic variant. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:612–617. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.070030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JY, Ugrasena DG, Lum DW, Lu Y, Yeoh AE. Xenobiotic and folate pathway gene polymorphisms and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in Javanese children. Hematol Oncol. 2011;29:116–123. doi: 10.1002/hon.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiurillo MA, Griman P, Santiago L, Torres K, Moran Y, Borjas L. Distribution of GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1 and TP53 disease-associated gene variants in native and urban Venezuelan populations. Gene. 2013;531:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csejtei A, Tibold A, Varga Z, Koltai K, Ember A, Orsos Z, Feher G, Horvath OP, Ember I, Kiss I. GSTM, GSTT and p53 polymorphisms as modifiers of clinical outcome in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:1917–1922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis MC, El-Sohemy A, Campos H. GSTT1 genotype modifies the association between cruciferous vegetable intake and the risk of myocardial infarction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:752–758. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandara C, Sayi J, Masimirembwa CM, Magimba A, Kaaya S, De Sommers K, Snyman JR, Hasler JA. Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 1A1 (Cyp1A1) and glutathione transferases (M1, T1 and P1) among Africans. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2002;40:952–957. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2002.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danileviciute A, Grazuleviciene R, Paulauskas A, Nadisauskiene R, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. Low level maternal smoking and infant birthweight reduction: Genetic contributions of GSTT1 and GSTM1 polymorphisms. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:161–161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dialyna IA, Miyakis S, Georgatou N, Spandidos DA. Genetic polymorphisms of CYP1A1, GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes and lung cancer risk. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:1829–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunna NR, Vure S, Sailaja K, Surekha D, Raghunadharao D, Rajappa S, Vishnupriya S. Deletion of GSTM1 and T1 genes as a risk factor for development of acute leukemia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:2221–2224. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.4.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eslami S, Sahebkar A. Glutathione-S-transferase M1 and T1 null genotypes are associated with hypertension risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 studies. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16:432–432. doi: 10.1007/s11906-014-0432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujihara J, Yasuda T, Iida R, Takatsuka H, Fujii Y, Takeshita H. Cytochrome P450 1A1, glutathione S-transferases M1 and T1 polymorphisms in Ovambos and Mongolians. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2009;(Suppl 1):S408–S410. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fundia AF, Weich N, Crivelli A, La Motta G, Larripa IB, Slavutsky I. Glutathione S-transferase gene polymorphisms in celiac disease and their correlation with genomic instability phenotype. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014;38:379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galal AM, Walker LA, Khan IA. Induction of GST and related events by dietary phytochemicals: Sources, chemistry, and possible contribution to chemoprevention. Curr Top Med Chem. 2015;14:2802–2821. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666141208110721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-González I, Mendoza-Alcocer R, Pérez-Mendoza GJ, Rubí-Castellanos R, González-Herrera L. Distribution of genetic variants of oxidative stress metabolism genes: Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) and glutathione S-transferase (GSTM1/GSTT1) in a population from Southeastern, Mexico. Ann Hum Biol. 2015;30:31–39. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2015.1126353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garte S, Gaspari L, Alexandrie AK, Ambrosone C, Autrup H, Autrup JL, Baranova H, Bathum L, Benhamou S, Boffetta P, et al. Metabolic gene polymorphism frequencies in control populations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:1239–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar PA, Hutz MH, Salzano FM, Hill K, Hurtado AM, Petzl-Erler ML, Tsuneto LT, Weimer TA. Polymorphisms of CYP1a1, CYP2e1, GSTM1, GSTT1, and TP53 genes in Amerindians. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2002;119:249–256. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates MA, Tworoger SS, Terry KL, Titus-Ernstoff L, Rosner B, De Vivo I, Cramer DW, Hankinson SE. Talc use, variants of the GSTM1, GSTT1, and NAT2 genes, and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2436–2444. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gra O, Mityaeva O, Berdichevets I, Kozhekbaeva Z, Fesenko D, Kurbatova O, Goldenkova-Pavlova I, Nasedkina T. Microarray-based detection of CYP1A1, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, GSTT1, GSTM1, MTHFR, MTRR, NQO1, NAT2, HLA-DQA1, and AB0 allele frequencies in native Russians. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14:329–342. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2009.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Amavizca BE, Orozco-Castellanos R, Ortíz-Orozco R, Padilla-Gutiérrez J, Valle Y, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez N, García-García G, Gallegos-Arreola M, Figuera LE. Contribution of GSTM1, GSTT1, and MTHFR polymorphisms to end-stage renal disease of unknown etiology in Mexicans. Indian J Nephrol. 2013;23:438–443. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.120342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy SI, Hiratsuka M, Narahara K, Endo N, El-Enany M, Moursi N, Ahmed MS, Mizugaki M. Genotype and allele frequencies of TPMT, NAT2, GST, SULT1A1 and MDR-1 in the Egyptian population. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55:560–569. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatagima A, Marques CF, Krieger H, Feitosa MF. Glutathione S-transferase M1 (GSTM1) and T1 (GSTT1) polymorphisms in a Brazilian mixed population. Hum Biol. 2004;76:937–942. doi: 10.1353/hub.2005.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He HR, You HS, Sun JY, Hu SS, Ma Y, Dong YL, Lu J. Glutathione S-transferase gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to acute myeloid leukemia: Meta-analyses. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:1070–1081. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hishida A, Terakura S, Emi N, Yamamoto K, Murata M, Nishio K, Sekido Y, Niwa T, Hamajima N, Naoe T. GSTT1 and GSTM1 deletions, NQO1 C609T polymorphism and risk of chronic myelogenous leukemia in Japanese. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2005;6:251–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo-Rangel G, Ortega-Martínez M, Cerda-Flores RM, Barrera-Saldaña HA. Polymorphisms in GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1, and GSTM3 genes and breast cancer risk in northeastern Mexico. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:6465–6471. doi: 10.4238/2015.June.11.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juronen E, Tasa G, Veromann S, Parts L, Tiidla A, Pulges R, Panov A, Soovere L, Koka K, Mikelsaar AV. Polymorphic glutathione S-transferase M1 is a risk factor of primary open-angle glaucoma among Estonians. Exp Eye Res. 2000;71:447–452. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabesch M, Hoefler C, Carr D, Leupold W, Weiland SK, von Mutius E. Glutathione S transferase deficiency and passive smoking increase childhood asthma. Thorax. 2004;59:569–573. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.016667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassogue Y, Quachouh M, Dehbi H, Quessar A, Benchekroun S, Nadifi S. Effect of interaction of glutathione S-transferases (T1 and M1) on the hematologic and cytogenetic responses in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib. Med Oncol. 2014;31:47–47. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0047-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Hong YC. GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 polymorphisms and associations between air pollutants and markers of insulin resistance in elderly Koreans. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:1378–1384. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus A, Zorman S, Berthier A, Polge C, Ramirez S, Michelland S, Sève M, Vertommen D, Rider M, Lentze N, et al. Glutathione S-transferases interact with AMP-activated protein kinase: Evidence for S-glutathionylation and activation in vitro. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinchid J, Chewaskulyoung B, Saeteng S, Lertprasertsuke N, Kasinrerk W, Cressey R. Effect of combined genetic polymorphisms on lung cancer risk in northern Thai women. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2009;195:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajinovic M, Labuda D, Richer C, Karimi S, Sinnett D. Susceptibility to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Influence of CYP1A1, CYP2D6, GSTM1, and GSTT1 genetic polymorphisms. Blood. 1999;93:1496–1501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S, Wei X, Gong C, Wei J, Chen Z, Chen X, Wang Z, Deng J. Significant association between asthma risk and the GSTM1 and GSTT1 deletion polymorphisms: An updated meta-analysis of case-control studies. Respirology. 2013;18:774–783. doi: 10.1111/resp.12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisker R, Perez-Briceño R, Granados J, Babinsky V, de Rubens J, Armendares S, Buentello L. Gene frequencies and admixture estimates in a Mexico City population. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1986;71:203–207. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330710207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Liu Y, Ran L, Shang H, Li D. GSTT1 and GSTM1 polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk in Asians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:2539–2544. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0778-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Li C, Gao J, Li K, Gao L, Gao T. Genetic polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferase and risk of vitiligo in the Chinese population. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2646–2652. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Kinsey M, Schiffman JD, Lessnick SL. Glutathione S-transferases in pediatric cancer. Front Oncol. 2011;1:39–42. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2011.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masimirembwa CM, Dandara C, Sommers DK, Snyman JR, Hasler JA. Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P4501A1, microsomal epoxide hydrolase, and glutathione S-transferases M1 and T1 in Zimbabweans and Venda of southern Africa. Pharmacogenetics. 1998;8:83–85. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199802000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masood N, Mubashar A, Yasmin A. Epidemiological factors related to GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes deletion in colon and rectum cancers: A case-control study. Cancer Biomark. 2015;15:583–589. doi: 10.3233/CBM-150498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouerhani S, Tebourski F, Slama MR, Marrakchi R, Rabeh M, Hassine LB, Ayed M, Elgaaïed AB. The role of glutathione transferases M1 and T1 in individual susceptibility to bladder cancer in a Tunisian population. Ann Hum Biol. 2006;33:529–535. doi: 10.1080/03014460600907517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajaud J, Kumar S, Rauch C, Morel F, Aninat C. Regulation of signal transduction by glutathione transferases. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:137676–137676. doi: 10.1155/2012/137676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palli D, Polidoro S, D’Errico M, Saieva C, Guarrera S, Calcagnile AS, Sera F, Allione A, Gemma S, Zanna I, et al. Polymorphic DNA repair and metabolic genes: A multigenic study on gastric cancer. Mutagenesis. 2010;25:569–575. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geq042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemble S, Schroeder KR, Spencer SR, Meyer DJ, Hallier E, Bolt HM, Ketterer B, Taylor JB. Human glutathione S-transferase theta (GSTT1): cDNA cloning and the characterization of a genetic polymorphism. Biochem J. 1994;300:271–276. doi: 10.1042/bj3000271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Morales R, Castro-Hernández C, Gonsebatt ME, Rubio J. Polymorphism of CYP1A1*2C, GSTM1*0, and GSTT1*0 in a Mexican Mestizo population: A similitude analysis. Hum Biol. 2008;80:457–465. doi: 10.3378/1534-6617-80.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Morales R, Méndez-Ramírez I, Castro-Hernández C, Martínez-Ramírez OC, Gonsebatt ME, Rubio J. Polymorphisms associated with the risk of lung cancer in a healthy Mexican Mestizo population: Application of the additive model for cancer. Genet Mol Biol. 2011;34:546–552. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572011005000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic D, Peterlin B. GSTM1-null and GSTT1-null genotypes are associated with essential arterial hypertension in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:574–577. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini S, Polimanti R, Porreca F, Martínez-Labarga C, De Stefano GF, Fuciarelli M. GSTT1 and GSTM1 gene polymorphisms in European and African populations. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:1225–1230. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafiee L, Saadat I, Saadat M. Glutathione S-transferase genetic polymorphisms (GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTO2) in three Iranian populations. Mol Biol Rep. 2010;37:155–158. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao DK, Shaik NA, Imran A, Murthy DK, Ganti E, Chinta C, Rao H, Shaik NS, Al-Aama JY. Variations in the GST activity are associated with single and combinations of GST genotypes in both male and female diabetic patients. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:841–848. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2924-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reszka E, Jablonowski Z, Wieczorek E, Jablonska E, Krol MB, Gromadzinska J, Grzegorczyk A, Sosnowski M, Wasowicz W. Polymorphisms of NRF2 and NRF2 target genes in urinary bladder cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:1723–1731. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1733-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruano-Ravina A, Pereyra MF, Castro MT, Pérez-Ríos M, Abal-Arca J, Barros-Dios JM. Genetic susceptibility, residential radon, and lung cancer in a radon prone area. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:1073–1080. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Guerra M, Pelallo-Martínez N, Díaz-Barriga F, Rothenberg SJ, Hernández-Cadena L, Faugeron S, Oropeza-Hernández LF, Guaderrama-Díaz M, Quintanilla-Vega B. Environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) exposure and DNA damage in Mexican children. Mutat Res. 2012;742:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval-Carrillo A, Aguilar-Duran M, Vázquez-Alaniz F, Castellanos-Juárez FX, Barraza-Salas M, Sierra-Campos E, Téllez-Valencia A, La Llave-León O, Salas-Pacheco JM. Polymorphisms in the GSTT1 and GSTM1 genes are associated with increased risk of preeclampsia in the Mexican mestizo population. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:2160–2165. doi: 10.4238/2014.January.17.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santovito A, Burgarello C, Cervella P, Delpero M. Polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 1A1, glutathione s-transferases M1 and T1 genes in Ouangolodougou (Northern Ivory Coast) Genet Mol Biol. 2010;33:434–437. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572010005000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K, Yi J, Shen X, Cai Y. Genetic polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferase genes GSTM1, GSTT1 and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurdle AB, Chang JH, Byrnes GB, Chen X, Dite GS, McCredie MR, Giles GG, Southey MC, Chenevix-Trench G, Hopper JL. A systematic approach to analysing gene-gene interactions: Polymorphisms at the microsomal epoxide hydrolase EPHX and glutathione S-transferase GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 loci and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:769–774. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stosic I, Grujicic D, Arsenijevic S, Brkic M, Milosevic-Djordjevic O. Glutathione S-transferase T1 and M1 polymorphisms and risk of uterine cervical lesions in women from central Serbia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:3201–3205. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.7.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui C, Ma J, He X, Wang G, Ai F. Interactive effect of glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 polymorphisms on hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:8235–8241. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tew KD, Townsend DM. Glutathione-s-transferases as determinants of cell survival and death. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:1728–1737. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toncheva DI, Von Ahsen N, Atanasova SY, Dimitrov TG, Armstrong VW, Oellerich M. Identification of NQO1 and GSTs genotype frequencies in Bulgarian patients with Balkan endemic nephropathy. J Nephrol. 2004;17:384–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild CP, Yin F, Turner PC, Chemin I, Chapot B, Mendy M, Whittle H, Kirk GD, Hall AJ. Environmental and genetic determinants of aflatoxin-albumin adducts in the Gambia. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:1–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000401)86:1<1::aid-ijc1>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Wang Y, Roe B, Pearson WR. Characterization of the human class Mu glutathione S-transferase gene cluster and the GSTM1 deletion. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3517–3527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wu X, Xiao Y, Chen M, Li Z, Wei X, Tang K. Genetic polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1, and evaluation of oxidative stress in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Med Res. 2014b;19:67–67. doi: 10.1186/s40001-014-0067-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Grek C, Ye ZW, Manevich Y, Tew KD, Townsend DM. Pleiotropic functions of glutathione S-transferase P. Adv Cancer Res. 2014a;122:143–175. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420117-0.00004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Ni Y, Zhang H, Pan Y, Ma J, Wang L. Association between GSTM1 and GSTT1 allelic variants and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuntar I, Petlevski R, Dodig S, Popovic-Grle S. GSTP1, GSTM1 and GSTT1 genetic polymorphisms and total serum GST concentration in stable male COPD. Acta Pharm. 2014;64:117–129. doi: 10.2478/acph-2014-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- World health organization http://www.who.int/ionizing_radiation/research/iarc/en/