ABSTRACT

Lincomycin A is a clinically important antimicrobial agent produced by Streptomyces lincolnensis. In this study, a new regulator designated LmbU (GenBank accession no. ABX00623.1) was identified and characterized to regulate lincomycin biosynthesis in S. lincolnensis wild-type strain NRRL 2936. Both inactivation and overexpression of lmbU resulted in significant influences on lincomycin production. Transcriptional analysis and in vivo neomycin resistance (Neor) reporter assays demonstrated that LmbU activates expression of the lmbA, lmbC, lmbJ, and lmbW genes and represses expression of the lmbK and lmbU genes. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) demonstrated that LmbU can bind to the regions upstream of the lmbA and lmbW genes through the consensus and palindromic sequence 5′-CGCCGGCG-3′. However, LmbU cannot bind to the regions upstream of the lmbC, lmbJ, lmbK, and lmbU genes as they lack this motif. These data indicate a complex transcriptional regulatory mechanism of LmbU. LmbU homologues are present in the biosynthetic gene clusters of secondary metabolites of many other actinomycetes. Furthermore, the LmbU homologue from Saccharopolyspora erythraea (GenBank accession no. WP_009944629.1) also binds to the regions upstream of lmbA and lmbW, which suggests widespread activity for this regulator. LmbU homologues have no significant structural similarities to other known cluster-situated regulators (CSRs), which indicates that they belong to a new family of regulatory proteins. In conclusion, the present report identifies LmbU as a novel transcriptional regulator and provides new insights into regulation of lincomycin biosynthesis in S. lincolnensis.

IMPORTANCE Although lincomycin biosynthesis has been extensively studied, its regulatory mechanism remains elusive. Here, a novel regulator, LmbU, which regulates transcription of its target genes in the lincomycin biosynthetic gene cluster (lmb gene cluster) and therefore promotes lincomycin biosynthesis, was identified in S. lincolnensis strain NRRL 2936. Importantly, we show that this new regulatory element is relatively widespread across diverse actinomycetes species. In addition, our findings provide a new strategy for improvement of yield of lincomycin through manipulation of LmbU, and this approach could also be evaluated in other secondary metabolite gene clusters containing this regulatory protein.

KEYWORDS: LmbU, LmbU homologues, Streptomyces, cluster-situated regulator, lincomycin, regulatory protein

INTRODUCTION

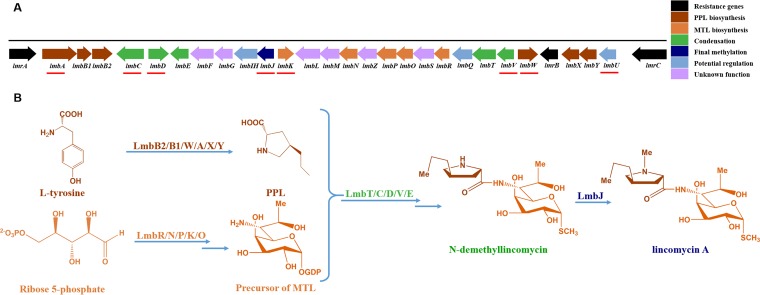

Streptomycetes spp. are Gram-positive bacteria that are known for their production of numerous secondary metabolites of medical and industrial importance (1). Lincomycin A is a medically important antibiotic that is produced by S. lincolnensis and has strong antibacterial activity against a variety of Gram-positive microorganisms and Mycoplasma. Lincomycin A is produced along with the less-useful lincomycin B, which has lower bioactivity than lincomycin A. The 35-kb lmb gene cluster (GenBank accession no. X79146.1) in S. lincolnensis industrial strain 78-11 was cloned and characterized by Peschke and collaborators (2). Subsequently, a very similar lmb gene cluster (GenBank accession no. EU124663.1) in S. lincolnensis strain ATCC 25466 was identified and sequenced and was heterologously expressed in Streptomyces coelicolor CH999 and M145 (3). Recently, the complete genome of S. lincolnensis wild-type strain NRRL 2936 (GenBank accession no. NZ_CP016438.1) was sequenced. The lmb gene cluster contains 26 open reading frames that encode putative biosynthetic or regulatory proteins and 3 putative resistance genes (2, 4) (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

The lmb gene cluster and the proposed biosynthetic pathway. (A) The lmb gene cluster contains 26 putative biosynthetic and regulatory genes and 3 resistance genes. The first gene of each putative operon is marked with a red line. (B) The lincomycin biosynthetic pathway and the proteins involved in it. Lincomycin biosynthesis can be divided into the following four steps: (i) biosynthesis of PPL (brown); (ii) biosynthesis of MTL (orange); (iii) condensation of PPL and MTL; (iv) final methylation. The genes and enzymes relevant to PPL biosynthesis are marked with brown, the genes and enzymes relevant to MTL biosynthesis are marked with orange, the genes and enzymes relevant to the condensation are marked with green, and the gene and enzyme relevant to methylation are marked with blue.

Lincomycin A is composed of two distinct building blocks: propylproline (PPL) and α-methylthiolincosaminide (MTL). The condensation of PPL and MTL leads to formation of N-demethyl-lincomycin, which is then converted to lincomycin A by methylation (5) (Fig. 1B; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The PPL biosynthetic pathway in S. lincolnensis was shown to be highly analogous to the biosynthetic pathways of the antibiotics tomaymycin (6), benzodiazepine (7), sibiromycin (8), and hormaomycin (9). l-Tyrosine was identified as a precursor of PPL through stable-isotope labeling (10), and it is converted into l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-DOPA) and then into 4-(3-carboxy-3-oxo-propenyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid (product 1) by the l-tyrosine hydroxylase LmbB2 and the l-DOPA-2,3-dioxygenase LmbB1 (11, 12). In the recent report, it was proposed that product 1 undergoes methylation by LmbW to generate product 2 (13, 14). The function of the putative γ-glutamyltransferase LmbA appears to indirectly remove the oxalyl residue of the product 2 to produce intermediate 3 (13). The subsequent isomerization and reduction reactions are catalyzed by LmbX and LmbY, respectively (see Fig. S1A).

On the other hand, it was proposed that MTL is derived from the pentose phosphate cycle (15, 16). In the early stages of MTL biosynthesis, the LmbR transaldolase catalyzes a transaldol reaction to produce the C8 sugar octulose 8-phosphate, which is subsequently isomerized to octose 8-phosphate by LmbN (15). Then, the putative LmbP kinase phosphorylates the octose 8-phosphate to octose 1,8-bisphosphate. The subsequent C8 dephosphorylation and nucleotidyl transfer reaction are catalyzed by the LmbK phosphatase and the LmbO octose 1-phosphate guanylyltransferase. The conversion of the resulting GDP-octose to GDP-d-α-d-lincosamide 9 is believed to be catalyzed by LmbL, LmbM, LmbS, LmbF, and LmbZ (16) (see Fig. S1B). The other enzymes, LmbT, LmbC, LmbN, LmbD, LmbV, and LmbE, have key roles in the use of two small-molecule thiols, mycothiol and ergothioneine, in the condensation of MTL and PPL (17) (see Fig. S1C).

The lmb gene clusters in wild-type strain NRRL 2936 and industrial strains 78-11 and B48 have identical nucleotide (nt) sequences (3). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and Southern hybridization analysis revealed that the lmb gene cluster has undergone duplication in industrial strain 78-11 (2), which suggested that this duplication contributes to the yield increase of lincomycin in strain 78-11. In addition, it has been suggested that genetic manipulations of regulatory genes that regulate the antibiotic biosynthesis also contribute to the increase in the yield of antibiotic. However, the regulatory mechanism of lincomycin biosynthesis is still unknown.

Gene clusters that encode antibiotic biosynthesis most often contain one or more regulators, which are known as cluster-situated regulators (CSRs). On the basis of their structural and functional characteristics and their amino-acid sequence similarities, these regulators are classified into several families, such as the Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory protein (SARP) family (18, 19), the TetR family (20–22), and the LuxR family (23, 24). However, no typical CSRs were identified in the lmb gene cluster.

In our previous studies, we found that deletion of the lmbIH and lmbQ genes does not prevent lincomycin production but only reduces it (our unpublished data). Sequence alignments show that LmbIH and LmbQ belong to the PmbA-TldD superfamily of putative modulators of DNA gyrase. This suggests that lmbIH and lmbQ may play regulatory roles in lincomycin biosynthesis. Meanwhile, a lmbU disruption mutant cannot produce lincomycin (25). And LmbU homologues are widely distributed in many other actinomycetes. Thus, we initially speculated that LmbU might be a cryptic CSR in the lmb gene cluster.

In the present study, we identified and characterized LmbU, which acts as a novel regulatory protein that does not belong to any of the known regulator superfamilies, and aimed to illuminate the function of LmbU and its homologues.

RESULTS

LmbU is a transcriptional regulator that promotes lincomycin biosynthesis.

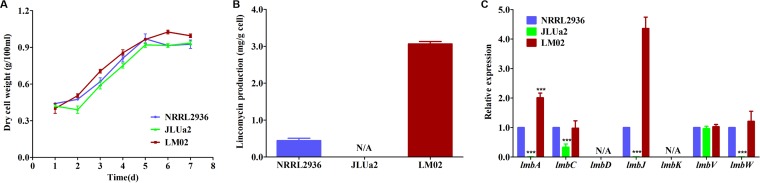

In our previous study, we speculated that the lmbU gene might encode a regulatory protein (25). To define the role of lmbU in lincomycin biosynthesis, three strains were analyzed: wild-type strain NRRL 2936, lmbU deletion strain JLUa2, and lmbU overexpression strain LM02. Both inactivation and overexpression of lmbU had no significant influences on cell growth (Fig. 2A) or colony morphology. However, inactivation of lmbU completely abolished the production of lincomycin (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast, compared with the wild-type strain, overexpression of lmbU led to a 5-fold increase in lincomycin production (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Effects of lmbU disruption and overexpression on growth and lincomycin production and qRT-PCR analysis. (A) Growth curves of S. lincolnensis strains NRRL 2936, JLUa2, and LM02. d, day. (B) Yield of lincomycin at day 5 for the NRRL 2936, JLUa2, and LM02 strains. Statistical significance is indicated versus wild-type results. (C) Transcriptional analysis of the lincomycin biosynthetic genes in the NRRL 2936, JLUa2, and LM02 strains. These strains were cultivated in fermentation medium FM2 for 3 days, and transcription analysis was carried out by qRT-PCR. The relative transcription levels of these genes were normalized using internal reference gene hrdB. The transcription level in NRRL 2936 was set to 1.0 (arbitrary units) for each gene. Data represent means ± standard deviations of results from three independent experiments. Statistical significance is indicated versus wild-type results. N/A, not analyzed. ***, P < 0.0001.

The lmb gene cluster contains eight potential promoters in addition to three resistance genes (Fig. 1A). To further evaluate whether LmbU acts as a transcriptional regulator, we used quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) to assess the influence of lmbU on the expression of seven target genes (lmbA, lmbC, lmbD, lmbJ, lmbK, lmbV, and lmbW) in three strains, NRRL 2936, JLUa2, and LM02. Compared to the wild-type strain results, the transcriptional levels of lmbA, lmbC, lmbJ, and lmbW were significantly decreased in the JLUa2 strain, and the transcriptional levels of lmbA and lmbJ were increased in the LM02 strain (Fig. 2C). Similar transcriptional levels of lmbC and lmbW were observed in the wild-type strain and LM02. In addition, the transcriptional level of lmbV was not influenced by the absence or presence of LmbU. It was not possible to detect the transcriptional levels of lmbD and lmbK in these three strains. Nonetheless, these data demonstrate that LmbU can activate the transcription of the lmbA, lmbC, lmbJ, and lmbW genes of the lincomycin gene cluster and thus can induce lincomycin production.

LmbU activates the promoters of lmbA, lmbC, lmbJ, and lmbW and represses the promoters of lmbU and lmbK in vivo.

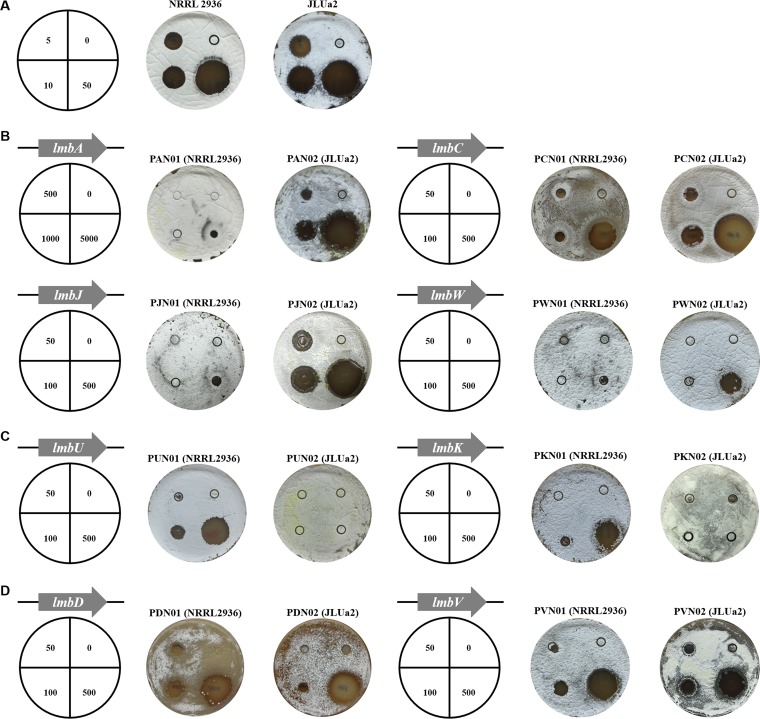

To further define the role of LmbU in lincomycin biosynthesis, the eight potential regions upstream of the lmbA, lmbU, lmbC, lmbD, lmbJ, lmbK, lmbV, and lmbW genes were amplified and fused to the Neor reporter gene to carry out Neor gene reporter assays. The NRRL 2936 and JLUa2 strains showed inhibition zones for the medium containing 5 μg/ml kanamycin (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

LmbU is required for activation or repression of its target promoters. (A) The NRRL 2936 (wild type) and JLUa2 (lmbU disruption mutant) strains show clearly visible inhibition zones on SMA medium containing 5 μg/ml kanamycin. (B) Effects of LmbU on the lmbAp, lmbCp, lmbJp, and lmbWp promoters. (C) Effects of LmbU on the lmbUp and lmbKp promoters. (D) Effects of LmbU on the lmbDp and lmbVp promoters. Strains were cultivated on SMA plates; the left plate in each panel represents the wild type, and the right plate represents the lmbU mutant strain. The activities of these promoters were determined by the Oxford cup method. Kanamycin concentrations were 0, 500, 1,000, and 5,000 μg/ml for lmbAp and 0, 50, 100, and 500 μg/ml for the other promoters.

When different promoter fusions were introduced into both the NRRL2936 strain and the JLUa2 strain, the reporter strains showed different degrees of resistance to kanamycin (Fig. 3). Among these, the lmbAp promoter showed strong activity, as strain PAN01 showed resistance to 5,000 μg/ml kanamycin (Fig. 3B). When lmbU was disrupted, the PAN02, PCN02, PJN02, and PWN02 strains showed reduced resistance to kanamycin (Fig. 3B). These data demonstrate that LmbU has a critical role in activation of the lmbAp, lmbCp, lmbJp, and lmbWp promoters. In sharp contrast, the PUN02 and PKN02 strains showed much higher resistance to kanamycin than the PUN01 and PKN01 strains (Fig. 3C), indicating that LmbU represses the lmbUp and lmbKp promoters. However, there were no significant differences in kanamycin resistance between PDN01 and PDN02 or between PVN01 and PVN02 (Fig. 3D), which suggests that LmbU has no effects on the activities of either the lmbDp promoter or the lmbVp promoter.

LmbU binds to an 8-bp palindromic sequence (5′-CGCCGGCG-3′) in the regions upstream of the lmbA and lmbW genes.

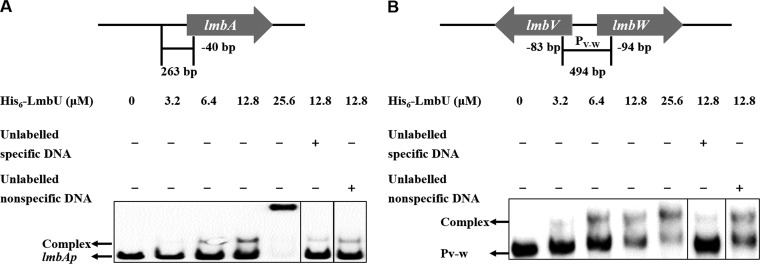

Bioinformatic analysis revealed that LmbU has no similarity to well-characterized regulators in Streptomyces or other strains. To identify LmbU binding sites, a series of electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were carried out with purified His6-LmbU and the DNA fragments upstream of lmbA and lmbU and the intergenic regions of lmbC-lmbD, lmbJ-lmbK, and lmbV-lmbW. His6-LmbU was observed to bind to the DNA fragments upstream of lmbA (designated lmbAp; 263 bp) (Fig. 4A) and lmbV-lmbW (designated PV-W; 494 bp) (Fig. 4B) in a concentration-dependent manner.

FIG 4.

Binding of His6-LmbU to the region upstream of lmbA (lmbAp) (A) and the intergenic region of lmbV-lmbW (PV-W) (B). Biotin-labeled lmbAp (263 bp, 5 ng) and PV-W (494 bp, 5 ng) probes were incubated with increasing concentrations (0, 3.2, 6.4, 12.8, and 25.6 μM) of His6-LmbU. EMSAs performed with 200-fold (lmbAp) and 100-fold (PV-W) excesses of unlabeled specific DNA or nonspecific DNA were added as controls to confirm the specificity of the band shifts. The DNA-protein complexes and the free probes are indicated by arrows.

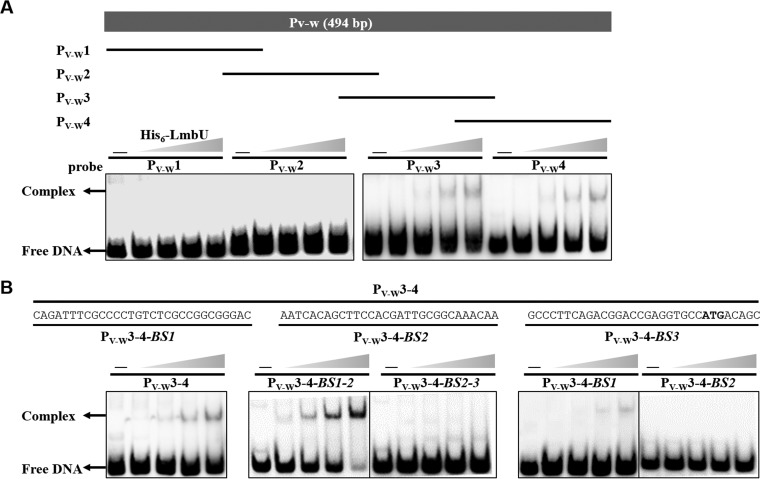

To determine the DNA-binding motif of LmbU, DNA fragment PV-W was divided into four DNA fragments with overlapping regions: PV-W1 (1 to 201 bp), PV-W2 (115 to 302 bp), PV-W3 (241 to 408 bp), and PV-W4 (317 to 494 bp). EMSAs were then carried out (Fig. 5A). Here, His6-LmbU bound to the PV-W3 and PV-W4 probes but not to the PV-W1 and PV-W2 probes, suggesting that the LmbU binding site(s) is located on the overlapping region of PV-W3 and PV-W4, which is close to the region upstream of lmbW. This is consistent with our observations that LmbU activates the transcription of lmbW but has no specific effect on the transcription of lmbV (Fig. 2C).

FIG 5.

Identification of LmbU binding region. (A) EMSAs of overlapping fragments of PV-W with His6-LmbU. Four overlapping fragments (PV-W1 to PV-W4) of PV-W are shown by lines. (B) Confirmation of His6-LmbU binding to the overlapping region PV-W3-4 and localization of the binding region on PV-W3-4-BS1. PV-W3-4-BS1-2 included PV-W3-4-BS1 and PV-W3-4-BS2, and PV-W3-4-BS2-3 included PV-W3-4-BS2 and PV-W3-4-BS3.

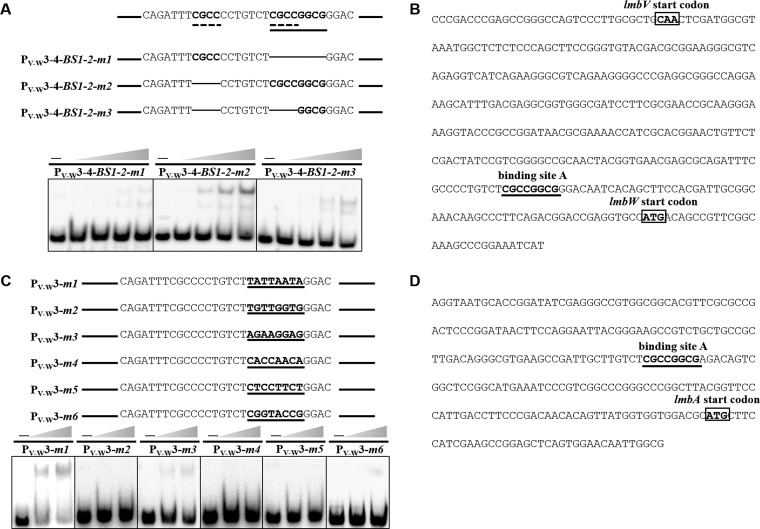

Subsequently, EMSAs were performed by amplifying the overlapping region of PV-W3 and PV-W4 (designated PV-W3-4). As expected, bands with strongly impeded migration were observed (Fig. 5B). When the subfragments were used to further analyze this region, LmbU was found to bind to PV-W3-4-BS1-2 and PV-W3-4-BS1. Higher levels of affinity of LmbU to PV-W3-4-BS1-2 were observed compared to the longer DNA fragment PV-W3-4 and the shorter DNA fragment PV-W3-4-BS1, which may have been due to the specialized structures of the target DNA. Thus, the LmbU binding site(s) is situated in PV-W3-4-BS1 (Fig. 5B). The two most likely binding sites of 5′-CGCC…CGCC-3′ and 5′-CGCCGGCG-3′ were identified via sequence analysis of PV-W3-4-BS1 (Fig. 6A). To estimate the contributions of these two DNA motifs to the DNA-binding activity of LmbU, three deletion mutations were introduced, as shown in Fig. 6A. We observed that LmbU strongly impeded the migration of the PV-W3-4-BS1-2-m2 probe when the first direct repeat was deleted. The PV-W3-4-BS1-2-m3 probe, where the entire region containing direct repeats was deleted but half of the palindromic sequence was retained, still showed weak binding to LmbU. However, the PV-W3-4-BS1-2-m1 probe, where the whole palindromic sequence was deleted, although one of the direct repeats was retained, completely inhibited the binding of LmbU. These results showed that one of the direct repeats could not bind to LmbU, but the other half of the palindromic sequence, GGCG, could bind to LmbU. These data suggest that the palindromic sequence 5′-CGCCGGCG-3′ (Fig. 6B, binding site A), which is located in the region from nt −59 to nt −66 upstream of the lmbW translation start codon (Fig. 6B), is important for LmbU binding. Furthermore, when five mutations were introduced into this motif in PV-W3, EMSA results showed that LmbU bound to the PV-W3-m1 probe, in which the motif was replaced with 5′-TATTAATA-3′. However, LmbU did not bind to the other probes (Fig. 6C). These data pinpoint the LmbU binding site and indicate that both palindromic sequence 5′-CGCCGGCG-3′ and palindromic sequence 5′-TATTAATA-3′ are important for LmbU binding.

FIG 6.

Identification of LmbU binding site. (A) PV-W3-4-BS1 contains two putative binding sites; one is a repetitive sequence (dotted line), and the other is a palindromic sequence (underlined). Deletion mutations were introduced into PV-W3-4-BS1-2 to produce mutant PV-W3-4-BS1-2-m1, PV-W3-4-BS1-2-m2, and PV-W3-4-BS1-2-m3 probes. The PV-W3-4-BS1-2-m1 probe contains the deletion of the entire palindromic sequence; the PV-W3-4-BS1-2-m2 probe contains the deletion of the first direct repeat. The PV-W3-4-BS1-2-m3 probe contains the deletion of the entire region with direct repeats. The concentration of His6-LmbU increased from left to right (0, 3.2, 6.4, 12.8, and 25.6 μM). (B) Nucleotide sequence of PV-W and the predicted binding site. The translation start site is indicated by the box. The predicted LmbU binding site, designated binding site A, is underlined. (C) Base substitution mutations were introduced into PV-W3 to produce mutant PV-W3-m1 (TATTAATA), PV-W3-m2 (TGTTGGTG), PV-W3-m3 (AGAAGGAG), PV-W3-m4 (CACCAACA), PV-W3-m5 (CTCCTTCT), and PV-W3-m6 (CGGTACCG) probes. The concentration of His6-LmbU increased from left to right (0, 6.4, and 12.8 μM). (D) Nucleotide sequence of the region upstream of lmbA and the predicted binding site. The translation start site is indicated by the box. The predicted LmbU binding site (designated binding site A) is underlined.

The region upstream of lmbA contains the conserved motif 5′-CGCCGGCG-3′, which is located in the region from nt −94 to nt −101 upstream of the lmbA translation start codon (Fig. 6D). However, the motif 5′-CGCC…CGCC-3′ is not found in this region. In addition, once this conserved motif was deleted (designated lmbAp-De), the lmbAp promoter was no longer controlled by LmbU (Fig. 7). Finally, we screened the other regions upstream of the lmb gene cluster but did not find the identified palindromic nucleotide sequence within them.

FIG 7.

LmbU does not activate the lmbAp promoter without the conserved motif 5′-CGCCGGCG-3′. The PADeN01 (NRRL 2936, wild-type strain) and PADeN02 (JLUa2, lmbU disruption mutant) strains were cultivated on SMA plates, and the activities were determined by the Oxford cup method. Kanamycin concentrations, 0, 500, 1,000, and 5,000 μg/ml.

To summarize, these data show that LmbU can bind directly to the regions upstream of the lmbA and lmbW genes through recognition of the conserved sequence 5′-CGCCGGCG-3′. However, LmbU does not bind to the regions upstream of the lmbU, lmbC, lmbJ, and lmbK genes, although, based on our experimental data, it also regulates the expression of these genes. These data thus indicate that the LmbU regulation of the lmbU, lmbC, lmbJ, and lmbK genes, transcribed under the control of the promoters containing no CGCCGGCG motif, is likely more complex than is currently thought.

LmbU homologues exist in many actinomycete species.

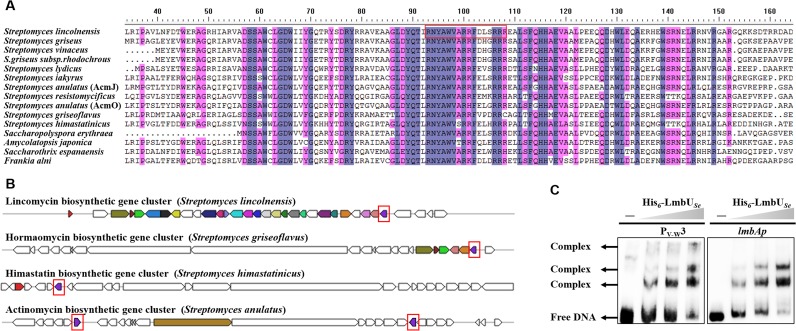

Various LmbU homologues can be found in many actinomycetes by searching in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (Fig. 8A). Protein sequence alignments show that LmbU from S. lincolnensis shares 48% to 72% identity with a number of homologues from other actinomycetes (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), some of which are located in biosynthetic gene clusters of secondary metabolites, such as HrmB (GenBank accession no. AEH41782.1) in the hormaomycin gene cluster from Streptomyces griseoflavus (12), HmtD (GenBank accession no. CBZ42138.1) in the himastatin gene cluster from Streptomyces himastatinicus, and AcmO (GenBank accession no. ADG27350.1) in the actinomycin gene cluster from Streptomyces anulatus (Fig. 8B).

FIG 8.

LmbU homologues in actinomycetes. (A) Sequence alignment of LmbU and its homologues from various actinomycete strains. (B) The location of the lmbU gene and its homologues in the lincomycin gene cluster (LmbU; ABX00623.1), the hormaomycin gene cluster (HrmB; AEH41782.1), the himastatin gene cluster (HmtD; CBZ42138.1), and the actinomycin gene cluster (AcmO; ADG27350.1). The lmbU gene and its homologues are indicated by the red boxes. (C) EMSAs of the LmbU homologue from S. erythraea D (LmbUSe; WP_009944629.1) (0, 6.4, 12.8, and 25.6 μM) with PV-W3 and lmbAp.

A hypothetical protein from Saccharopolyspora erythraea (LmbUSe) was found to have 60% identity to LmbU (see Table S1). To determine whether this LmbU homologue has DNA-binding activity similar to that of LmbU, lmbUSe was cloned and successfully expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). The His6-LmbUSe recombinant protein was purified. EMSA results showed that His6-LmbUSe also binds to the PV-W3 and lmbAp probes (Fig. 8C). Thus, these data provide strong indications that LmbU homologues generally act as transcriptional regulators in S. erythraea and other actinomycete strains.

Interestingly, at least two binding complexes were observed for the His6-LmbUSe protein compared to the single complex observed for the His6-LmbU protein from S. lincolnensis, indicating that LmbUSe shows binding specificity that is slightly different from that shown by the LmbU protein. In addition, we also carried out modeling of the LmbU protein using SwissModel (https://www.swissmodel.expasy.org/interactive; data not shown) (26), and we identified two potential DNA-binding domains (DBD), a putative helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif (amino acids [aa] 80 to 102) and a putative ribbon-helix-helix (RHH) motif (aa 167 to 206). The structure of the HTH motif of LmbU shares 13% sequence identity with that of the ParB superfamily protein Spo0J (GenBank accession no. WP_011173975.1) from Thermus thermophilus (27). The structure of the RHH motif of LmbU shares 10% to 25% sequence identity with that of the RHH family of DNA-binding proteins, such as alginate and motility regulator Z (AmrZ; GenBank accession no. ARG85760.1) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (28). These two proteins are functionally distinct from LmbU, thus demonstrating that LmbU has no structural similarity to any known Streptomyces regulatory protein. Furthermore, we have observed three different amino acids in the HTH motif and a number of different amino acids in the RHH motif in comparing LmbU from S. lincolnensis to the LmbU homologue from S. erythraea (see Fig. S3). Different amino acids may be responsible for the DNA-binding specificity.

DISCUSSION

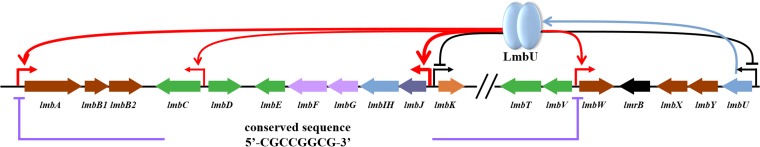

Studies on the model organism S. coelicolor and other antibiotic-producing Streptomyces species have revealed that the production of secondary metabolites generally occurs at the stationary-growth stage, which is under the control of cascade regulation systems (29–31). The biosynthetic genes of antibiotics are generally clustered together on chromosomes or plasmids (31, 32) and usually contain one or more CSRs (33) that provide a direct contributions to antibiotic production through transcriptional regulation of other biosynthetic genes in the clusters (18, 34). In the present study, we identified and characterized LmbU, a novel transcriptional regulator that is involved in the regulation of lincomycin biosynthesis. We also identified LmbU homologues in other actinomycetes species and proposed a regulatory mechanism of LmbU in lincomycin biosynthesis (Fig. 9). Our results revealed that LmbU activates the lmbA, lmbC, and lmbW genes and represses the lmbU and lmbK genes, thus regulating lincomycin biosynthesis. LmbU binds to the regions upstream of lmbA and lmbW directly by recognizing the conserved sequence 5′-CGCCGGCG-3′ but does not bind to the upstream region of lmbU, lmbC and lmbK in vitro.

FIG 9.

Proposed model of transcriptional regulation by LmbU. LmbU binds to the regions upstream of lmbA and lmbW directly by recognizing the conserved sequence 5′-CGCCGGCG-3′ but does not bind to the sequence upstream of lmbU, lmbC, and lmbK in vitro. Red arrows indicate transcriptional activation, and black perpendicular lines indicate transcriptional repression.

In this study, we have demonstrated that lincomycin biosynthesis in S. lincolnensis NRRL 2936 is promoted by LmbU. Considering the main building blocks used in lincomycin biosynthesis, the pathway can be divided into two subpathways: those of MTL and PPL (Fig. 1B). The MTL pathway is not yet well understood. Five genes (lmbR, lmbN, lmbP, lmbO, and lmbK) were identified to be involved in MTL biosynthesis (15, 16) (Fig. 1B). LmbU represses the lmbKp promoter in vivo. In contrast, LmbU does not bind to lmbKp in EMSAs (data not shown). Except for lmbK, these other genes involved in MTL biosynthesis are very likely to be transcribed from the same operon, which is controlled by the lmbVp promoter (Fig. 1A). However, LmbU has no effects on the lmbVp promoter. These data indicate that LmbU regulates MTL biosynthesis indirectly.

In contrast, the lmbA, lmbB1, lmbB2, lmbW, lmbX, and lmbY genes are involved in PPL biosynthesis (13). Among these, lmbA, lmbB1, and lmbB2 share the same operon (2) (Fig. 1A), which is transcribed under the control of the lmbAp promoter. Coexpression of lmbW and metK might increase the production of lincomycin A while also decreasing the proportion of lincomycin B (14) (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). LmbU binds directly to the regions upstream of lmbA and lmbW and consequently activates their transcription. Thus, LmbU not only may have an important role in PPL biosynthesis but also may actively inhibit the production of lincomycin B.

The condensation of the intermediate metabolites PPL and MTL and the involvement of mycothiol and ergothioneine are carried out by lmbV, lmbT, lmbC, lmbN, lmbD, and lmbE (17) (see Fig. S1C). Although LmbU cannot directly bind to the regions upstream of lmbC and lmbJ (which is located upstream of lmbE), it can activate the lmbCp and lmbJp promoters in vivo (Fig. 3B). LmbU also upregulates the expression of lmbJ, which converts N-demethyl-lincomycin A to lincomycin A. Here, LmbU may increase lincomycin production by upregulation of the expression levels of its target genes.

We have demonstrated that LmbU activates the lmbAp, lmbCp, lmbJp, and lmbWp promoters but represses the lmbUp and lmbKp promoters. Potentially, these promoters may be regulated through different regulatory mechanisms. We have proposed a model here for LmbU-mediated regulation of lincomycin biosynthesis. In the case of the lmbAp and lmbWp promoters, we have demonstrated that LmbU activates the two promoters through binding to the conserved 8-bp palindromic sequence 5′-CGCCGGCG-3′ within them. In contrast, LmbU regulates the lmbUp, lmbCp, lmbJp, and lmbKp promoters only in vivo but does not bind to them in vitro. Hence, we can speculate that LmbU not only acts as a DNA-binding protein but also interacts with another regulatory protein(s), consequently indirectly influencing the expression of target genes lmbU, lmbCp, lmbJ, and lmbK. This suggests that the transcriptional regulatory mechanism of LmbU in lincomycin biosynthesis is very complex.

Also, we have identified numerous LmbU homologues in different actinomycetes, with most seen in Streptomyces species. We have shown that the biosynthetic gene clusters of hormaomycin, himastatin, and actinomycin also contain LmbU homologues. The conserved motif 5′-CGCCGGCG-3′ for LmbU binding is also present in putative regions upstream of the genes (from bp −400 to the start codon) within these three clusters in multiple sites (four sites in the hormaomycin gene cluster, one site in the himastatin gene cluster, and seven sites in the actinomycin gene cluster). Thus, we propose that these LmbU homologues (i.e., HrmB, HmtD, and AcmO) have important regulatory roles in the biosynthesis of hormaomycin, himastatin, and actinomycin.

As described previously, most DNA-binding domains of the CSRs contain a helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif, a helix-loop-helix (HLH) motif, or a ribbon-helix-helix (RHH) motif (35–37). Generally, in CSRs, one of the α-helices is inserted into the major groove of the target DNA and thus binds to the DNA backbone (38). However, LmbU homologues have no significant structural similarities to other known CSRs, and structural analysis of LmbU suggested there are two potential DNA-binding domains (DBD), an HTH motif (aa 80 to 102) and an RHH motif (aa 167 to 206). These results indicated that LmbU and its homologues belong to a new family of regulatory proteins. Recently, it was reported that the polar and positively charged amino acid arginine (R) is important for the DNA binding of different CSRs (39, 40). For example, MarR family member PcaV from S. coelicolor cannot bind to its target DNA when its R15 is replaced with an alanine (R15A) but can bind to the DNA when its R15 is replaced with a similarly charged amino acid lysine (R15K) (41). AraC/XylS family regulator AdpA recognizes the nucleotide bases of the HTH1 motif in the DNA-binding domain, where residues R262 and R266 are essential for binding of AdpA to the G7′ and G2 guanines (38). On the basis of the amino acid sequence alignment of the LmbU homologues, we identified a conserved arginine-rich region (Fig. 8; indicated by the red box) which overlaps the HTH motif of LmbU, suggesting that the HTH motif may be a DNA-binding domain. Further studies for identification of the structure of LmbU are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

In summary, we have identified LmbU from the lincomycin biosynthetic pathway as a positive CSR and have demonstrated that the LmbU homologues, which were previously annotated as “hypothetical proteins,” are actually new regulatory proteins. We have demonstrated that LmbU promotes lincomycin production through its regulation of the expression of the biosynthetic genes. By applying this knowledge, we believe it will be possible to develop new molecular-engineering strategies to use this regulator activity of LmbU to increase the relative levels of lincomycin A production and, potentially, to decrease the content of the less-useful by-product lincomycin B in industrial strains. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that the members of this family of regulatory proteins are distributed across other secondary metabolite biosynthetic pathways. The lack of significant structural similarities between LmbU and other CSRs also indicates that LmbU and its homologues belong to a new family of pathway-specific regulators.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and the plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli JM83 and E. coli BL21(DE3) were used for routine molecular cloning and protein overexpression, respectively. E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 (42) was used for E. coli-S. lincolnensis conjugation. S. lincolnensis wild-type strain NRRL 2936 was used for gene disruption and overexpression.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. lincolnensis | ||

| NRRL 2936 | Wild type, lincomycin producer | NRRL, USA |

| JLUa2 | NRRL 2936 ΔlmbU | 25 |

| LM02 | NRRL 2936 attBΦC31::pEU139 | This study |

| PAN01 | NRRL 2936 attBΦC31::pAN152 | This study |

| PAN02 | JLUa2 attBΦC31:: pAN152 | This study |

| PUN01 | NRRL 2936 attBΦC31:: pUN152 | This study |

| PUN02 | JLUa2 attBΦC31:: pUN152 | This study |

| PCN01 | NRRL 2936 attBΦC31:: pCN152 | This study |

| PCN02 | JLUa2 attBΦC31:: pCN152 | This study |

| PDN01 | NRRL 2936 attBΦC31:: pDN152 | This study |

| PDN02 | JLUa2 attBΦC31:: pDN152 | This study |

| PJN01 | NRRL 2936 attBΦC31:: pJN152 | This study |

| PJN02 | JLUa2 attBΦC31:: pJN152 | This study |

| PKN01 | NRRL 2936 attBΦC31:: pKN152 | This study |

| PKN02 | JLUa2 attBΦC31:: pKN152 | This study |

| PVN01 | NRRL 2936 attBΦC31:: pVN152 | This study |

| PVN02 | JLUa2 attBΦC31:: pVN152 | This study |

| PWN01 | NRRL 2936 attBΦC31:: pWN152 | This study |

| PWN02 | JLUa2 attBΦC31:: pWN152 | This study |

| PADeN01 | NRRL 2936 attBΦC31:: pADeN152 | This study |

| PADeN02 | JLUa2 attBΦC31:: pADeN152 | This study |

| S. erythraea | Wild type | 33 |

| E. coli | ||

| JM83 | F′ ara Δ(lac-pro AB) rpsL (Strr)a Φ80 lacZΔM15 | 25 |

| BL21(DE3) | F− ompT hsdS gal dcm | Novagen |

| ET12567/pUZ8002 | dam-13::Tn9 dcm-6 hsdM; contains the nontransmissible RP4 derivative plasmid pUZ8002 | 26 |

| M. luteus 28001 | Indicator strain used for the bioassay method of lincomycin production | CGMCC |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSET152 | Integrative vector based on ΦC31 integrase | 46 |

| pIB139 | Integrative vector based on ΦC31 integrase, ermE*p | 44 |

| pEU139 | pIB139 with lmbU inserted downstream of ermE*p | This study |

| pAN152 | pSET152 with the Neor reporter gene controlled by lmbAp | This study |

| pUN152 | pSET152 with the Neor reporter gene controlled by lmbUp | This study |

| pCN152 | pSET152 with the Neor reporter gene controlled by lmbCp | This study |

| pDN152 | pSET152 with the Neor reporter gene controlled by lmbDp | This study |

| pJN152 | pSET152 with the Neor reporter gene controlled by lmbJp | This study |

| pKN152 | pSET152 with the Neor reporter gene controlled by lmbKp | This study |

| pVN152 | pSET152 with the Neor reporter gene controlled by lmbVp | This study |

| pWN152 | pSET152 with the Neor reporter gene controlled by lmbWp | This study |

| pET-28a (+) | E. coli expression vector | Novagen |

| pLU-1 | LmbU cloned in NdeI/EcoRI sites of pET-28a (+) | This study |

| pLU-2 | LmbUSe cloned in NdeI/HindIII sites of pET-28a (+) | This study |

Strr, streptomycin resistance.

The E. coli strains were cultivated at 37°C in liquid or on solid Luria-Bertani media. The S. lincolnensis wild-type strain and the mutant strains were cultivated at 28°C in liquid culture media in a shaking incubator (230 rpm). SM medium (4 g/liter yeast extract, 10 g/liter glucose, 0.4 g/liter K2HPO4, 4 g/liter polypeptone, 0.2 g/liter KH2PO4, 50 mg/liter MgSO4, 340 g/liter sucrose) is used for DNA extraction (43), fermentation medium FM1 (20 g/liter lactose, 20 g/liter glucose, 10 g/liter polypeptone, 10 g/liter corn steep liquor) is used for growth curve assays, and FM2 (20 g/liter lactose, 20 g/liter glucose, 10 g/liter polypeptone, 10 g/liter corn steep liquor, 4 g/liter CaCO3) is used for lincomycin production assays (25). For preparation of spore suspensions, solid standard methods agar (SMA) medium is used (43). The media were supplemented with 50 μg/ml apramycin, 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and/or 10 μg/ml thiostrepton as appropriate.

Construction of lmbU disruption mutant JLUa2 and lmbU overexpression strain LM02.

The lmbU JLUa2 disruption mutant was described in our previous study (25). Briefly, lmbU mutant JLUa2 was constructed by the replacement of the internal region of lmbU (from +333 to +565 relative to the lmbU start codon) with the thiostrepton resistance gene. For lmbU overexpression, a fragment covering the coding region of lmbU was amplified by PCR using the primer pair U139-F/U139-R, digested with NdeI/EcoRI, and ligated into the NdeI/EcoRI-restricted E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle plasmid pIB139 (44), where lmbU is under the control of the strong constitutive promoter ermE*p. The resulting plasmid, pEU139, was introduced into wild-type strain NRRL 2936 by conjugal transfer and was integrated into the attB site of the chromosome by the use of ΦC31 recombinase to generate lmbU-overexpressing strain LM02.

Growth curves and lincomycin production analysis.

The S. lincolnensis wild-type strain and the mutant strains were cultivated in the FM1 and FM2 fermentation media at 28°C. The dry weight of cells from FM1 cultures was determined as the measurement of biomass formation. The supernatant from FM2 culture was used for lincomycin production analysis (25). Briefly, the S. lincolnensis strains were inoculated into 500-ml flasks with 100 ml FM2 from seed cultures and were incubated at 28°C for 5 days in a shaking incubator (230 rpm). The supernatants were collected by centrifugation (8,000 rpm for 10 min) and were used to measure lincomycin production. The bioassay method was performed using Micrococcus luteus 28001 as an indicator strain, according to reference 49. M. luteus was cultured at 37°C in medium III (5 g/liter polypeptone, 1.5 g/liter beef extract, 3 g/liter yeast extract, 3.5 g/liter NaCl, 3.68 g/liter K2HPO4, 1.32 g/liter KH2PO4, 1 g/liter glucose, 18 g/liter agar) for 16 to 18 h. The cell pellets were washed with sterile 0.9% NaCl solution to prepare the M. luteus culture suspension. Lincomycin standard solutions (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 μg/ml) were used to prepare the standard curves. Inhibition zone diameters were linear with the logarithmic values of the concentrations of the lincomycin standard solutions. The concentrations of the samples were calculated according to the standard curves.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR).

RNA was extracted from the NRRL 2936, JLUa2, and LM02 strains after 3 days of culture in FM2 medium, using RNA extraction kits (Aidlab Biotech, China). Before extraction, the mycelia were ground in liquid nitrogen (22). After 1 h of incubation with RNase-free DNase I (TaKaRa, Japan) at 28°C, the concentrations and quality of RNA were analyzed using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cDNA from 1 μg RNA was synthesized using reverse transcription Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) (RNase-free) kits (TaKaRa, Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out with SYBR green PCR master mix (ToYoBo, Japan). The PCR conditions were as follows: 98°C for 3 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 20 s; and, finally, 72°C for 5 min. PCR was performed in triplicate for each transcript. Primer pairs qA-F/R, qC-F/R, qD-F/R, qJ-F/R, qK-F/R, qV-F/R, qW-F/R, and qhrdB-F/R are listed in Table 2. The amplicons were 100 bp to 200 bp from the internal gene sequences. To normalize the gene expression, hrdB was treated as the positive internal control. The transcription levels of the tested genes were determined using the threshold cycle (2−ΔΔCT) method (45).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this studya

| Primer and use | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| Construction of lmbU overexpression strain LM02 | |

| U139-F | TCTAATACATATGGTGGTGAGGTCGAATTTATCGGTTGCGGACAGG |

| U139-R | GCGGAATTCGGATGGACGGTGGGGGGTGGAGGT |

| qRT-PCR | |

| qA-F | CGACACCGCAAGCCTTCTCCGAT |

| qA-R | CGAGCAACCGCAGCCAGCCAC |

| qC-F | CGCGACGACGAGTTCACCC |

| qC-R | TACGGCCCGACCGAGACCAAC |

| qD-F | CCGGGCTGCTGCCGCACACG |

| qD-R | TCAGGGCCAGACGCAGGCTCAGG |

| qJ-F | AGCGACGGGATCGTGTTTG |

| qJ-R | CCTGGTCCTTCAGTGCCTCA |

| qK-F | GGTTTCGCCCTGGCCGTCGTCAC |

| qK-R | GTCGTCGTGGAGGCAGGTGAAGAAG |

| qV-F | CCCACCAGCACCGTCATG |

| qV-R | TGACCCGTGAGCAGTTCGTG |

| qW-F | CGGTTCCCGCACCAGAAGA |

| qW-R | GCTGCGTGAGGACGTGGATG |

| qhrdB-F | GCGGGCGTCGTCTCCATGC |

| qhrdB-R | TGCGAGCGCGAGGGGTGA C |

| Neor gene reporter assays in vivo | |

| pAneo-1 | CTTCGCTATTACGCCAGAGGTAATGCACCGGATATCG |

| pAneo-2 | CATCTTGTTCAATCATGCGTCCACCACCATAAC |

| pUneo-1 | CTTCGCTATTACGCCAGCGTTGGGTTGCCGCTTTGGATGGTC |

| pUneo-2 | CATCTTGTTCAATCATGCGGCTGCCATCCCTTTCTCACG |

| pCneo-1 | CTTCGCTATTACGCCAGGAAGGACGTCGAAGAGGTCACAGCG |

| pCneo-2 | CATCTTGTTCAATCATGCCTCCGCCATCGGGTACCGGCCCG |

| pDneo-1 | CTTCGCTATTACGCCAGCTCGTCCCCGTCCGATGGCAG |

| pDneo-2 | CATCTTGTTCAATCATGTCCGCCGCTGTGACCTCTTC |

| pJneo-1 | CTTCGCTATTACGCCAGCCGTCGGCGTCGTCGTGGAGG |

| pJneo-2 | CATCTTGTTCAATCATTGAATTCTCTTTCCTCACCAG |

| pKneo-1 | CTTCGCTATTACGCCAGCGATCTGCTCGTCCTGCGTCAGCAG |

| pKneo-2 | CATCTTGTTCAATCATGCCACCGTCTCCCTGCGGCCGCTCG |

| pVneo-1 | CTTCGCTATTACGCCAGGTGTCTTGGAGTTCGATGATTTCCG |

| pVneo-2 | CATCTTGTTCAATCATCTCGATGGCGTAAATGGCTCTCTCC |

| pWneo-1 | CTTCGCTATTACGCCAGGGACGTTCCACTCCGCACAGCGTGT |

| pWneo-2 | CATCTTGTTCAATCATGGCACCTCGGTCCGTCTGAAGGGCT |

| pWneo-3 | ATGATTGAACAAGATGGATTGCACGCAG |

| pWneo-4 | GGCCGATTCATTAATGCAGTCAGAAGAACTCGTCAAGAAG |

| pA-De1-P2 | CCGACTGTCTAGACAAGCAATCGGCTTC |

| pA-De1-P3 | GATTGCTTGTCTAGACAGTCGGCTCCGGC |

| Overexpression of the recombinant proteins | |

| U-F28a | AGCCATATGGTGAGGTCGAATTTAT |

| U-R28a | GCAGGGATCCGGTGCTCAGAGTTAG |

| Use-F28a | TACTCGCCATATGAATTCGTCGGCCTGGTTCCTC |

| Use-R28a | GCGGAATTCTGCGGGCACACGCCGTAAGGATG |

| Electrophoretic mobility shift assays | |

| lmbA-BF | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG AGGTAATGCACCGGATATCG |

| lmbA-BR | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG GCCAATTGTTCCACTGAGCT |

| Pv-w-F | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG GTGAGCCAGGCCCGCAGGTG |

| Pv-w-R | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG CGGGCAGTTGGGAGAGGGTG |

| EMSA-B* | Biotin-AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG |

| Pv-w1-1-B | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG CGCAGGTGTCTTCCCTCGTCG |

| Pv-w1-2-B | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG GCCTCGTCAAATGCTTTCCTGG |

| Pv-w2-1-B | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG CCGGGTGTACGACGCGGAAGG |

| Pv-w2-2-B | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG AGTTGCGGCCCCGACGGATAG |

| Pv-w3-1-B | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG CGCCGGATAACGCGAAAACCAT |

| Pv-w3-2-B | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG GCTGTCATGGCACCTCGGTCC |

| Pv-w4-1-B | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG CAGATTTCGCCCCTGTCTCGCCG |

| Pv-w4-2-B | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG CGGGCAGTTGGGAGAGGGTGAAAGC |

| Pv-w-BS1-F | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG CAGATTTCGCCCCTGTC |

| Pv-w-BS1-R | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG GTCCCGCCGGCGAGAC |

| Pv-w-BS2-F | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG AATCACAGCTTCCACGATTG |

| Pv-w-BS2-R | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG TTGTTTGCCGCAATCG |

| Pv-w-BS3-F | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG GCCCTTCAGACGGACC |

| Pv-w-BS3-R | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG GCTGTCATGGCACCTCG |

| BS1-2-m1-F | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAGCAGATTTCCTGTCTGGACAATCACAGCTTCCACGATTG |

| BS1-2-m2-F | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG CAGATTTCCTGTCTGGAC |

| BS1-2-m3-F | AGCCAGTGGCGATAAGCAGATTTCCTGTCTGGACAATCACAGCTTCCACG |

| PV-W3-m1-R2 | TGTCCTATTAATAAGACAGGGGCGAAATCTGC |

| PV-W3-m2-F3 | CTGTCTTATTAATAGGACAATCACAGCTTCCAC |

| PV-W3-m2-R2 | TGTCCCACCAACAAGACAGGGGCGAAATCTGC |

| PV-W3-m2-F3 | CTGTCTTGTTGGTGGGACAATCACAGCTTCCAC |

| PV-W3-m3-R2 | TGTCCCTCCTTCTAGACAGGGGCGAAATCTGC |

| PV-W3-m3-F3 | CTGTCTAGAAGGAGGGACAATCACAGCTTCCAC |

| PV-W3-m4-R2 | TGTCCTGTTGGTGAGACAGGGGCGAAATCTGC |

| PV-W3-m4-F3 | CTGTCTCACCAACAGGACAATCACAGCTTCCAC |

| PV-W3-m5-R2 | TGTCCAGAAGGAGAGACAGGGGCGAAATCTGC |

| PV-W3-m5-F3 | CTGTCTCTCCTTCTGGACAATCACAGCTTCCAC |

| PV-W3-m6-R2 | TGTCCCGGTACCGAGACAGGGGCGAAATCTGC |

| PV-W3-m6-F3 | CTGTCTCGGTACCGGGACAATCACAGCTTCCAC |

Italics and underlining, restriction enzyme cutting site; bold, italics, and underlining, sequences homologous to plasmid pSET152; bold only, sequences homologous to bold and italic sequences of pWneo-3; bold and underlining, mutation of LmbU binding site A.

Assay of neomycin resistance (Neor) reporter system in vivo.

The reporter gene encoding Neor was amplified by PCR using primer pair pWneo-3/4. The regions upstream (all expressed relative to the translation start codon) of the lmbA (bp −223 to −1), lmbU (bp −329 to −1), lmbC (bp −513 to −1), lmbD (bp −439 to −1), lmbJ (bp −388 to −1), lmbK (bp −441 to −1), lmbV (bp −364 to −1), and lmbW (bp −456 to −1) genes were amplified using primer pairs pAneo-1/2, pUneo-1/2, pCneo-1/2, pDneo-1/2, pJneo-1/2, pKneo-1/2, pVneo-1/2, and pWneo-1/2, respectively, as listed in Table 2. The two DNA fragments (promoter and gene encoding Neor) were inserted into the PvuII site of the integrative vector pSET152 (46) using Super Efficiency Fast Seamless Cloning kits (DoGene, China). In Table 2, the DNA sequences in bold, italic, and underlined text are homologous to the flanking sequences of the PvuII site of pSET152. The resulting reporter plasmids pAN152, pUN152, pCN152, pDN152, pJN152, pKN152, pVN152, and pWN152 that contained ΦC31 integrase were introduced into the NRRL 2936 and JLUa2 strains and were integrated into the attB site of the chromosome to generate the PAN01, PUN01, PCN01, PDN01, PJN01, PKN01, PVN01, and PWN01 strains and the PAN02, PUN02, PCN02, PDN02, PJN02, PKN02, PVN02, and PWN02 strains, respectively. The transformants that contained the corresponding plasmids were streaked on SMA plates and used for kanamycin sensitivity analysis performed with the Oxford cup method. Deletion of binding site A from the region upstream of lmbA was achieved using overlap PCR. For the first step, primer pairs pAneo-1/pA-De1-P2 and pA-De1-P3/pAneo-2 were used to make the PCR amplicons which were used as templates for the second PCR.

Overexpression and purification of recombinant proteins in E. coli.

The lmbU gene and its homologue from S. erythraea (lmbUSe) were amplified by PCR using primer pairs U-F28a/R28a and Use-F28a/R28a listed in Table 2. The amplified DNA fragments were cloned into the corresponding sites of the pET-28a (+) vector (Novagen) after digestion with NdeI/BamHI or NdeI/EcoRI to provide expression plasmids pLU-1 and pLU-2. The resulting plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) for protein expression. The strains were cultivated at 37°C in 250-ml flasks with 30 ml Luria-Bertani medium, with an agitator tip speed of 190 rpm. Isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to reach a final concentration of 1 mM when the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached about 0.6. Then, the cultures were incubated at 16°C overnight. The cell pellets were washed twice with buffer (0.1 M phosphate buffer solution, pH 7.5) after centrifugation (8,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C) and then resuspended in the same buffer. The proteins were released by sonication on ice and were purified using nickel-iminodiacetic acid–agarose chromatography (WeiShiBoHui, China). The purified proteins were dialyzed against binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol, 20 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 1.2% glycerol) and were concentrated using 10-kDa-cutoff centrifugal filter units (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The target proteins were analyzed using 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and were quantified using the Bradford assay with bovine serum albumin as a standard (47).

EMSAs.

EMSAs were carried out as described previously (48), using chemiluminescent EMSA kits (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). DNA fragments were amplified by PCR using the primer pairs listed in Table 2. Biotin-labeled primer EMSA-B* was used in the second-round PCR to make the labeled probes. The binding reaction mixture contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol, 20 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 1.2% glycerol, and 50 μg/ml poly(dI·C). Deletion and mutation of the probes were achieved using overlap PCR.

Homology modeling.

We constructed the LmbU model using the online software SwissModel (https://www.swissmodel.expasy.org/interactive).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Ju Chu for providing the industrial strain. We thank Bang-Ce Ye for kindly sharing the EMSA technology. We are grateful to the other members of our laboratory, and specifically to Rui-Da Wang, Ya-Jing Kang, Hui Xia, and Jian Mo, for critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (3120026).

B.H., J.Y., and H.W. designed the experiments; B.H., Y.L., L.T., and X.Z. carried out the experiments; B.H., J.Y., H.W., H.Z., and M.G. analyzed the data; B.H. and H.W. wrote the manuscript; H.P. discussed the experimental design and contributed to the manuscript. All of us assisted with critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00447-17.

For a commentary on this article, see https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00559-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hopwood DA. 2007. Streptomyces in nature and medicine: the antibiotic makers. Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peschke U, Schmidt H, Zhang HZ, Piepersberg W. 1995. Molecular characterization of the lincomycin-production gene cluster of Streptomyces lincolnensis 78-11. Mol Microbiol 16:1137–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koberská M, Kopecký J, Olsovská J, Jelínková M, Ulanova D, Man P, Flieger M, Janata J. 2008. Sequence analysis and heterologous expression of the lincomycin biosynthetic cluster of the type strain Streptomyces lincolnensis ATCC 25466. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 53:395–401. doi: 10.1007/s12223-008-0060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang HZ, Schmidt H, Piepersberg W. 1992. Molecular cloning and characterization of two lincomycin-resistance genes, lmrA and lmrB, from Streptomyces lincolnensis 78-11. Mol Microbiol 6:2147–2157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spízek J, Rezanka T. 2004. Lincomycin, cultivation of producing strains and biosynthesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 63:510–519. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li W, Chou S, Khullar A, Gerratana B. 2009. Cloning and characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster for tomaymycin, an SJG-136 monomeric analog. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:2958–2963. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02325-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu YF, Phelan V, Ntai I, Farnet CM, Zazopoulos E, Bachmann BO. 2007. Benzodiazepine biosynthesis in Streptomyces refuineus. Chem Biol 14:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W, Khullar A, Chou SC, Sacramo A, Gerratana B. 2009. Biosynthesis of sibiromycin, a potent antitumor antibiotic. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:2869–2878. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02326-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Höfer I, Crüsemann M, Radzom M, Geers B, Flachshaar D, Cai XF, Zeeck A, Piel J. 2011. Insights into the biosynthesis of hormaomycin, an exceptionally complex bacterial signaling metabolite. Chem Biol 18:381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witz DF, Hessler EJ, Miller TL. 1971. Bioconversion of tyrosine into the propylhygric acid moiety of lincomycin. Biochemistry 10:1128–1133. doi: 10.1021/bi00783a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neusser D, Schmidt H, Spizèk J, Novotnà J, Peschke U, Kaschabeck S, Tichy P, Piepersberg W. 1998. The genes lmbB1 and lmbB2 of Streptomyces lincolnensis encode enzymes involved in the conversion of l-tyrosine to propylproline during the biosynthesis of the antibiotic lincomycin A. Arch Microbiol 169:322–332. doi: 10.1007/s002030050578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novotná J, Honzátko A, Bednár P, Kopecký J, Janata J, Spízek J. 2004. l-3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl alanine-extradiol cleavage is followed by intramolecular cyclization in lincomycin biosynthesis. Eur J Biochem 271:3678–3683. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiraskova P, Gazak R, Kamenik Z, Steiningerova L, Najmanova L, Kadlcik S, Novotna J, Kuzma M, Janata J. 2016. New concept of the biosynthesis of 4-alkyl-l-proline precursors of lincomycin, hormaomycin, and pyrrolobenzodiazepines: could a γ-glutamytransferase cleave the C-C bond? Front Microbiol 7:276. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pang AP, Du L, Lin CY, Qiao J, Zhao GR. 2015. Co-overexpression of lmbW and metK led to increased lincomycin A production and decreased byproduct lincomycin B content in an industrial strain of Streptomyces lincolnensis. J Appl Microbiol 119:1064–1074. doi: 10.1111/jam.12919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasaki E, Lin CI, Lin KY, Liu HW. 2012. Construction of the octose 8-phosphate intermediate in lincomycin A biosynthesis: characterization of the reactions catalyzed by LmbR and LmbN. J Am Chem Soc 134:17432–17435. doi: 10.1021/ja308221z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin CI, Sasaki E, Zhong A, Liu HW. 2014. In vitro characterization of LmbK and LmbO: identification of GDP-d-erythro-α-d-gluco-octose as a key intermediate in lincomycin A biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc 136:906–909. doi: 10.1021/ja412194w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao QF, Wang M, Xu DX, Zhang QL, Liu W. 2015. Metabolic coupling of two small-molecule thiols programs the biosynthesis of lincomycin A. Nature 518:115–119. doi: 10.1038/nature14137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu G, Tian YQ, Yang HH, Tan HR. 2005. A pathway-specific transcriptional regulatory gene for nikkomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces ansochromogenes that also influences colony development. Mol Microbiol 55:1855–1866. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurniawan YN, Kitani S, Maeda A, Nihira T. 2014. Differential contributions of two SARP family regulatory genes to indigoidine biosynthesis in Streptomyces lavendulae FRI-5. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:9713–9721. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5988-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang YY, Pan GH, Zou ZZ, Fan KQ, Yang KQ, Tan HR. 2013. JadR*-mediated feed-forward regulation of cofactor supply in jadomycin biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol 90:884–897. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramos JL, Martínez-Bueno M, Molina-Henares AJ, Terán W, Watanabe K, Zhang X, Gallegos MT, Brennan R, Tobes R. 2005. The TetR family of transcriptional repressors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 69:326–356. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.326-356.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu YP, Yan TT, Jiang LB, Wen Y, Song Y, Chen Z, Li JL. 2013. Characterization of SAV7471, a TetR-family transcriptional regulator involved in the regulation of coenzyme A metabolism in Streptomyces avermitilis. J Bacteriol 195:4365–4372. doi: 10.1128/JB.00716-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng ZL, Bown L, Tahlan K, Bignell DR. 2015. Regulation of coronafacoyl phytotoxin production by the PAS-LuxR family regulator CfaR in the common scab pathogen Streptomyces scabies. PLoS One 10:e0122450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mo S, Yoon YJ. 2016. Interspecies complementation of the LuxR family pathway-specific regulator involved in macrolide biosynthesis. J Microbiol Biotechnol 26:66–71. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1510.10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lv CX, Yang J, Ye J, Wu HZ, Zhang HZ. 2008. Knockout and retro-complementation of a lincomycin biosynthetic gene lmbU. J East China Univ Sci Technol 34:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang H, Grove A. 2013. The transcriptional regulator TamR from Streptomyces coelicolor controls a key step in central metabolism during oxidative stress. Mol Microbiol 87:1151–1161. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonard TA, Butler PJ, Löwe J. 2004. Structural analysis of the chromosome segregation protein Spo0J from Thermus thermophilus. Mol Microbiol 53:419–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pryor EE Jr, Waligora EA, Xu B, Dellos-Nolan S, Wozniak DJ, Hollis T. 2012. The transcription factor AmrZ utilizes multiple DNA binding modes to recognize activator and repressor sequences of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes. PloS Pathog 8:e1002648. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martín JF, Liras P. 2010. Engineering of regulatory cascades and networks controlling antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces. Curr Opin Microbiol 13:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Wezel GP, McDowall KJ. 2011. The regulation of the secondary metabolism of Streptomyces: new links and experimental advances. Nat Prod Rep 28:1311–1333. doi: 10.1039/c1np00003a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu G, Chater KF, Chandra G, Niu GQ, Tan HR. 2013. Molecular regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:112–143. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00054-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Rourke S, Wietzorrek A, Fowler K, Corre C, Challis GL, Chater KF. 2009. Extracellular signalling, translational control, two repressors and an activator all contribute to the regulation of methylenomycin production in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol 71:763–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li XX, Yu TF, He Q, McDowall KJ, Jiang BY, Jiang ZB, Wu LZ, Li GW, Li QL, Wang SM, Shi YY, Wang LF, Hong B. 2015. Binding of a biosynthetic intermediate to AtrA modulates the production of lidamycin by Streptomyces globisporus. Mol Microbiol 96:1257–1271. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu WS, Zhang QL, Guo J, Chen Z, Li JL, Wen Y. 2015. Increasing avermectin production in Streptomyces avermitilis by manipulating the expression of a novel TetR-family regulator and its target gene product. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:5157–5173. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00868-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaiser BK, Stoddard BL. 2011. DNA recognition and transcriptional regulation by the WhiA sporulation factor. Sci Rep 1:156. doi: 10.1038/srep00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JM, Won HS, Kang SO. 2014. The C-terminal domain of the transcriptional regulator BldD from Streptomyces coelicolor A3 (2) constitutes a novel fold of winged-helix domains. Proteins 82:1093–1098. doi: 10.1002/prot.24481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards AL, Meijer DH, Guerra RM, Molenaar RJ, Alberta JA, Bernal F, Stiles CD, Walensky LD. 2016. Challenges in targeting a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor with hydrocarbon-stapled peptides. ACS Chem Biol 11:3146–3153. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao MD, Ohtsuka J, Nagata K, Miyazono KI, Zhi YH, Ohnishi Y, Tanokura M. 2013. Complex structure of the DNA-binding domain of AdpA, the global transcription factor in Streptomyces griseus, and a target duplex DNA reveals the structural basis of its tolerant DNA sequence specificity. J Biol Chem 288:31019–31029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.473611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong MS, Fuangthong M, Helmann JD, Brennan RG. 2005. Structure of an OhrR-ohrA operator complex reveals the DNA binding mechanism of the MarR family. Mol Cell 20:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim D, Poole K, Strynadka NC. 2002. Crystal structure of the MexR repressor of the mexRAB-oprM multidrug efflux operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem 277:29253–29259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis JR, Brown BL, Page R, Sello JK. 2013. Study of PcaV from Streptomyces coelicolor yields new insights into ligand-responsive MarR family transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res 41:3888–3900. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacNeil DJ, Klapko LM. 1987. Transformation of Streptomyces avermitilis by plasmid DNA. J Ind Microbiol 2:209–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01569542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilkinson CJ, Hughes-Thomas ZA, Martin CJ, Böhm I, Mironenko T, Deacon M, Wheatcroft M, Wirtz G, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. 2002. Increasing the efficiency of heterologous promoters in Actinomycetes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 4:417–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD.. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bierman M, Logan R, O'Brien K, Seno ET, Rao RN, Schoner BE. 1992. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene 116:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liao CH, Yao L, Xu Y, Liu WB, Zhou Y, Ye BC. 2015. Nitrogen regulator GlnR controls uptake and utilization of non-phosphotransferase-system carbon sources in actinomycetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:15630–15635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508465112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pharmacopoeia Commission of the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China 1990. Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China, 1990 ed, appendices 113–116. China Medico-Pharmaceutical Science & Technology Publishing House, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.