Abstract

Bacteria of the genus Pectobacterium are economically important plant pathogens that cause soft rot disease on a wide variety of plant species. Here, we report the genome sequence of Pectobacterium carotovorum strain SCC1, a Finnish soft rot model strain isolated from a diseased potato tuber in the early 1980’s. The genome of strain SCC1 consists of one circular chromosome of 4,974,798 bp and one circular plasmid of 5524 bp. In total 4451 genes were predicted, of which 4349 are protein coding and 102 are RNA genes.

Keywords: Pectobacterium, Soft rot, Plant pathogen, Necrotroph, Potato, Finland

Introduction

10.1601/nm.3241 species are economically important plant pathogens that cause soft rot and blackleg disease on a range of plant species across the world [1, 2]. The main virulence mechanism employed by 10.1601/nm.3241 is the secretion of vast amounts of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes [1, 3]. Due to their ability to effectively macerate plant tissue for acquisition of nutrients, 10.1601/nm.3241 species are considered classical examples of necrotrophic plant pathogens. Among the 10.1601/nm.3241 species, 10.1601/nm.10935 has the widest host range while potato is the most important crop affected in temperate regions [1, 4]. 10.1601/nm.10935 strain SCC1 was isolated from a diseased potato tuber in Finland in the early 1980’s [5]. It is highly virulent on model plant hosts such as tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) as well as on the original host, potato (Solanum tuberosum). For three decades, the strain has been used as a model strain in the study of virulence mechanisms of 10.1601/nm.3241 as well as in the study of plant defense mechanisms against necrotrophic plant pathogens ([e.g. [6–13]). Here we describe the annotated genome sequence of 10.1601/nm.10935 strain SCC1.

Organism information

Classification and features

10.1601/nm.10935 strain SCC1 is a Gram-negative, motile, non-sporulating, and facultatively anaerobic bacterium that belongs to the order of 10.1601/nm.29303 within the class of 10.1601/nm.2068. Cells of strain SCC1 are rod shaped with length of approximately 2 μm in the exponential growth phase (Fig. 1). Strain SCC1 is pathogenic causing soft rot disease in plants. It was originally isolated from a diseased potato tuber in Finland in 1982 [5]. It also provokes maceration symptoms on model plants Arabidopsis, tobacco, and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), and is used as a soft rot model in research.

Fig. 1.

Photomicrograph of Gram stained exponentially growing Pectobacterium carotovorum SCC1 cells. A light microscope with 100× magnification was used

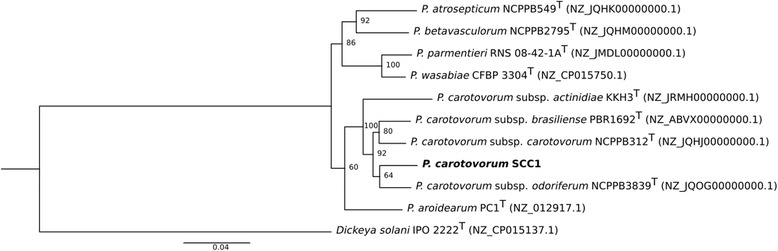

Strain SCC1 has previously been described belonging to 10.1601/nm.3242 based on biochemical properties such as its ability to grow at +37 °C and in 5% NaCl, its sensitivity to erythromycin, its ability to assimilate lactose, melibiose and raffinose but not sorbitol, and its inability to produce reducing sugars from sucrose and acid from α-methyl glucoside [14]. A phylogenetic tree generated based on seven housekeeping genes (dnaN, fusA, gyrB, recA, rplB, rpoS and gyrA) clusters strain SCC1 together with other 10.1601/nm.10935 strains (Fig. 2). However, sequence based phylogenetic analysis was inconclusive regarding the subspecies status. Overall, the phylogeny of 10.1601/nm.3241 species and subspecies is currently in turmoil and assigning strains to subspecies is challenging [15].

Fig. 2.

Maximum likelihood tree of Pectobacterium carotovorum SCC1 and other closely related Pectobacterium strains. The phylogenetic tree was constructed from the seven housekeeping genes (dnaN, fusA, gyrB, recA, rplB, rpoS and gyrA). The concatenated sequences were aligned using MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program (version 7) with default parameters [42]. The phylogenetic tree was built in RAxML (Randomized Axelerated Maximum Likelihood) program with Maximum likelihood (ML) inference [43]. 88 different nucleotide substitution models were tested with jModelTest 2.0 and the best model was selected using Akaike information criterion (AIC) [44]. Bootstrap values from 1000 replicates are shown in each branch. Dickeya solani IPO2222 was used as the outgroup. Type strains are marked with T after the strain name. GenBank accession numbers are presented in the parentheses. The scale bar indicates 0.04 substitutions per nucleotide position

10.1601/nm.10935 strain SCC1 has been deposited at the International Center for Microbial Resources - French collection of plant-associated bacteria (accession: 10.1601/strainfinder?urlappend=%3Fid%3DCFBP+8537). MIGS of strain SCC1 is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Classification and general features of Pectobacterium carotovorum strain SCC1 [46]

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [47] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [48] | ||

| Class Gammaproteobacteria | TAS [49, 50] | ||

| Order Enterobacterales | TAS [51] | ||

| Family Pectobacteriaceae | TAS [51] | ||

| Genus Pectobacterium | TAS [52, 53] | ||

| Species Pectobacterium carotovorum | TAS [52, 54] | ||

| Strain: SCC1 (10.1601/strainfinder?urlappend=%3Fid%3DCFBP+8537) | TAS [5] | ||

| Gram stain | Negative | IDA | |

| Cell shape | Rod | IDA | |

| Motility | Motile | IDA | |

| Sporulation | Non-sporulating | NAS [51] | |

| Temperature range | Mesophile, able to grow at 37 °C | TAS [14] | |

| Optimum temperature | ~28 °C | IDA | |

| pH range; Optimum | Unknown | ||

| Carbon source | Sucrose, lactose, melibiose, raffinose | IDA,TAS [14] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Potato | TAS [5] |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Able to grow in 5% NaCl | TAS [14] |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Facultatively anaerobic | NAS [51] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Pathogenic | NAS [53] |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Finland | TAS [5] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection | 1982 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 60° 13′ 36.15” N | NAS |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | 25° 00′ 54.77″ E | NAS |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Unknown |

aEvidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [55]

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

10.1601/nm.10935 strain SCC1 has been used as a model soft rot pathogen in the field of plant-pathogen interactions ever since its isolation in the 1980’s. The sequencing of the genome of strain SCC1 was initiated in 2008 in order to further facilitate its use as a model pathogen.

The project was carried out jointly by the Institute of Biotechnology, Department of Biosciences and Department of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Helsinki, Finland. The genome was sequenced, assembled and annotated. The final sequence contains two scaffolds representing one chromosome and one plasmid. The sequence of the chromosome contains one gap of estimated length of 3788 bp. The genome sequence is deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers CP021894 (chromosome) and CP021895 (plasmid). Summary information of the project is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS 31 | Finishing quality | One gap remaining, otherwise finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Standard 454 and Solid libraries |

| MIGS 29 | Sequencing platforms | 454, SOLiD, Sanger |

| MIGS 31.2 | Fold coverage | Chromosome 40×, plasmid 67× |

| MIGS 30 | Assemblers | gsAssembler v 1.1.03.24 |

| MIGS 32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal |

| Locus Tag | SCC1 | |

| Genbank ID | CP021894, CP021895 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | July 27, 2017 | |

| GOLD ID | ||

| BIOPROJECT | PRJNA379819 | |

| MIGS 13 | Source Material Identifier | 10.1601/strainfinder?urlappend=%3Fid%3DCFBP+8537 |

| Project relevance | Plant pathogen |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

After isolation from potato in 1982, 10.1601/nm.10935 strain SCC1 has been stored in 22% glycerol at −80 °C. For preparation of genomic DNA, the strain was first grown overnight on solid LB medium (10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 10 g NaCl, and 15 g agar per one liter of medium) at 28 °C. A single colony was then picked and grown overnight in 10 ml of liquid LB medium at 28 °C with shaking. Cells were harvested by centrifugation for 20 min at 3200 g at 4 °C and resuspended into TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA). SDS (5% w/v) and Proteinase K (1 mg/ml) were used to break the cells for one hour at 50 °C. Genomic DNA was extracted using phenol-chloroform purification followed by ethanol precipitation. The quantity and quality of the DNA was assessed by spectrophotometry and agarose gel electrophoresis.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Genome sequencing was performed at DNA and Genomics Laboratory, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Finland. Genomic DNA was sequenced using 454 (454 Life Sciences/Roche), SOLiD3 (Life Technologies) and ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies) instruments. DNA was fragmented into approximate size of 800 bp using Nebulizer (Roche) followed by standard fragment 454 library with the GS FLX series reagents. For the SOLiD library genomic DNA was fragmented with a Covaris S2 Sonicator (Covaris Inc.) to approximate size of 250 bp. The library was prepared using the SOLiD library kit (Life technologies).Newbler (version 1.1) was used to assemble 366,453 pyrosequencing reads (77,6 Mbp) in approximate length of 240 bp with default settings into 100 large (>1000 bp) contigs. GAP4 program (Staden package) was used for contig editing, primer design for PCRs and primer walking, and finishing the genome. Gaps were closed using PCR and traditional primer walking Sanger sequencing method. Finally, SOLiD reads were mapped to the genome and fifteen single genomic positions were fixed. Final sequencing coverages were 40× in genome and 67× in plasmid sequences.

Genome annotation

Coding sequences were predicted using the Prodigal gene prediction tool [16]. GenePRIMP [17] was run to correct systematic errors made by Prodigal and to reanalyze the remaining intergenic regions for missed CDSs. Functional annotation for the predicted genes was performed using the PANNZER annotation tool [18]. The annotation was manually curated with information from publications and the following databases: COG [19], KEGG [20], CDD [21], UniProt and NCBI non-redundant protein sequences. To identify RNA genes, RNAmmer v1.2 [22] (rRNAs) and tRNAscan-SE [23] (tRNAs) were used. Clusters of Orthologous Groups assignments and Pfam domain predictions were done using the WebMGA server [24]. Transmembrane helices were predicted with TMHMM [25] and Phobius [26]. For signal peptide prediction, SignalP 4.1 [27] was used. CRISPRFinder [28] was used to detect Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPRs).

Genome properties

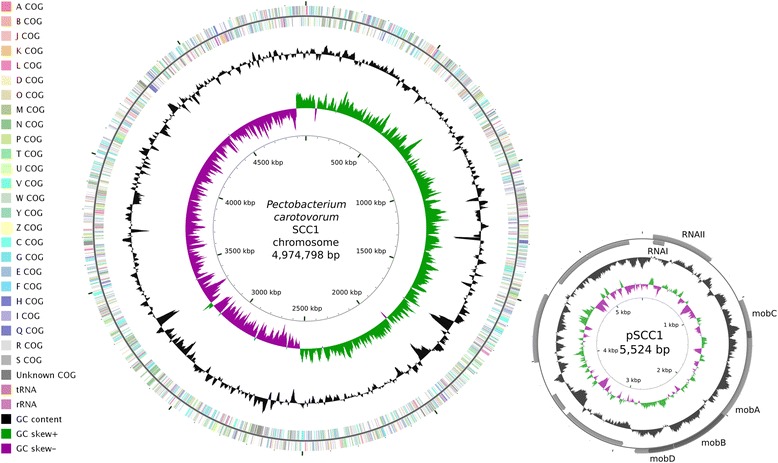

The genome of 10.1601/nm.10935 SCC1 consists of one circular 4,974,798 bp chromosome and one circular 5524 bp plasmid (Table 3, Fig. 3). The total genome size is 4,980,322 bp with an overall G + C content of 51.85% (Table 4). A total of 4451 genes were predicted, out of which 4440 are chromosomal and 11 reside on the plasmid. 4349 (97.71%) genes are protein coding and 102 (2.29%) are RNA genes (77 tRNA, 22 rRNA, and 3 other RNA genes). Of the 4349 protein coding genes, 3812 (87.65%) could be assigned to COG functional categories (Table 5).

Table 3.

Summary of P. carotovorum SCC1 genome: one chromosome and one plasmid

Fig. 3.

Circular maps of the chromosome and plasmid of Pectobacterium carotovorum SCC1. Rings from the outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (colored by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (colored by COG categories), GC content, GC skew. Maps were generated using the CGView Server [45]

Table 4.

Genome statistics

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,980,322 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 4,314,063 | 86.62 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 2,580,564 | 51.85 |

| DNA scaffolds | 2 | |

| Total genes | 4451 | 100.00 |

| Protein coding genes | 4349 | 97.71 |

| RNA genes | 102 | 2.29 |

| Pseudo genes | NA | NA |

| Genes in internal clusters | NA | NA |

| Genes with function prediction | 3955 | 88.86 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3812 | 85.64 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 3782 | 84.97 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 428 | 9.62 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 939 | 21.10 |

| CRISPR repeats | 5 |

Table 5.

Number of genes associated with general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 183 | 4.21 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 2 | 0.05 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 332 | 7.63 | Transcription |

| L | 161 | 3.70 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0.00 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 40 | 0.92 | Cell cycle control, Cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| V | 61 | 1.40 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 242 | 5.56 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 241 | 5.54 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 114 | 2.62 | Cell motility |

| U | 122 | 2.81 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 152 | 3.50 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 248 | 5.70 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 376 | 8.65 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 435 | 10.00 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 94 | 2.16 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 177 | 4.07 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 103 | 2.37 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 318 | 7.31 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 67 | 1.54 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 445 | 10.23 | General function prediction only |

| S | 358 | 8.23 | Function unknown |

| – | 537 | 12.35 | Not in COGs |

The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the genome

Insights from the genome sequence

10.1601/nm.10935 strain SCC1 harbors a small cryptic plasmid of 5524 bp, pSCC1. The plasmid contains sequences for RNAI and RNAII, two non-coding RNAs involved in replication initiation and control in enterobacterial RNA priming plasmids such as ColE1 [29]. A similar replication region has previously been described in the small cryptic plasmid pEC3 of 10.1601/nm.3242 strain 10.1601/strainfinder?urlappend=%3Fid%3DIFO+3380 [30]. In addition to the two RNA genes, pSCC1 was predicted to contain nine protein-coding genes. Four of these (mobABCD) encode mobilization proteins. The mob locus is required for mobilization of non-self-transmissible plasmids and is found on many enterobacterial plasmids including pEC3 [31]. No function could be assigned to the remaining five genes on pSCC1. One of them, SCC1_4463, is very similar to genes found in many 10.1601/nm.3091 genomes, especially those of genera 10.1601/nm.3148, 10.1601/nm.3092 and 10.1601/nm.3291, whereas similar genes to the other four on pSCC1 are not widely present in other sequenced genomes.

10.1601/nm.3241 infection is characterized by maceration symptoms caused by the secretion of a large arsenal of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes. Accordingly, the genome of 10.1601/nm.10935 strain SCC1 was found to contain genes for eleven pectate lyases (pelABCILWXZ, hrpW, SCC1_1311, and SCC1_2381), one pectin lyase (pnl), four polygalacturonases (pehAKNX), one oligogalacturonate lyase (ogl), three cellulases (celSV, bcsZ), one rhamnogalacturonate lyase (rhiE), two pectin methylesterases (pemAB), and two pectin acetylesterases (paeXY). In addition, the genome harbors two genes encoding proteases previously characterized as plant cell wall-degrading enzymes (prt1, prtW) as well as a number of putative proteases, some of which may function in plant cell wall degradation. Different 10.1601/nm.3241 species and strains have been found to harbor very similar collections of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes [32], and the number and types of enzymes in the genome of strain SCC1 fit this picture well.

Protein secretion plays an essential role in soft rot pathogenesis [33]. The most important secretion system in 10.1601/nm.3241 is the type II secretion system, also known as the Out system (outCDEFGHIJKLMN), which transports proteins from the periplasmic space into the extracellular environment [34]. It is responsible for the secretion of most plant cell wall-degrading enzymes such as pectinases and cellulases as well as some other virulence factors such as the necrosis-inducing protein Nip [33, 35]. Furthermore, 10.1601/nm.3241 genomes typically harbor multiple type I secretion systems, which secrete proteases and adhesins [33]. At least four type I secretion systems are encoded in the genome of 10.1601/nm.10935 SCC1 (prtDEF, SCC1_1144–1146, SCC1_1589–1591, and SCC1_3286–3288). Strain SCC1 also harbors a type III secretion system cluster (SCC1_2406–2432), which has previously been characterized in this strain and shown to affect the speed of symptom development during infection [6, 36]. Overall, the role of the type III secretion system in 10.1601/nm.3241 is not well understood and 10.1601/nm.3254 and 10.1601/nm.29447 seem to lack it completely [32, 37]. The type IV secretion system has been shown to have a minor contribution to virulence of 10.1601/nm.3247 [38]. However, it is sporadically distributed among 10.1601/nm.3241 strains [33], and no type IV secretion genes could be found from the genome of 10.1601/nm.10935 SCC1. Finally, the type VI secretion system has also been shown to have a small effect on virulence at least in some 10.1601/nm.3241 species [32, 39]. In 10.1601/nm.10935 SCC1, one type VI secretion system cluster is present in the genome (SCC1_0988–1002).

Soft rot pathogens have been suggested to be able to use insect vectors in transmission, and indeed, certain 10.1601/nm.10935 strains can infect Drosophila flies and persist in their guts [40]. This ability has been linked to the Evf (10.1601/nm.3165 virulence factor) protein [41]. The evf gene is present in the genome of 10.1601/nm.10935 SCC1 suggesting that the strain may have the ability to interact with insects.

Conclusions

In this study, we presented the annotated genome sequence of the pectinolytic plant pathogen 10.1601/nm.10935 SCC1 consisting of a chromosome of 4,974,798 bp and a small cryptic plasmid of 5524 bp. Strain SCC1 was originally isolated from a diseased potato tuber and it has been used as a model strain to study interactions between soft rot pathogens and their host plants for decades. In accordance with the pathogenic lifestyle, the genome of strain SCC1 was found to harbor a large arsenal of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes similar to other sequenced 10.1601/nm.3241 genomes. In addition, an insect interaction gene, evf, is present in the genome of strain SCC1 suggesting the possibility of insects as vectors or alternative hosts for this strain. The genome sequence will drive further the use of 10.1601/nm.10935 SCC1 as a model plant pathogen.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

We acknowledge the support of the Academy of Finland (Center of Excellence program 2006–2011, grants 213,509 and 129,628 and grants 136,470, 120,821, and 128,566), Biocentrum Helsinki, Biocenter Finland, University of Helsinki, the Emil Aaltonen foundation, the Finnish Doctoral Program in Computational Sciences FICS, the Viikki Doctoral Program in Molecular Biosciences, and the Finnish Doctoral Program in Plant Science.

Authors’ contributions

ETP and MPi initiated the study and provided the strain and background information. HH isolated the genomic DNA. PL, PA and LP designed sequencing strategy and performed genome sequencing and assembly. PK, LH and ON annotated the genome. ON manually corrected the functional annotation. MPa and MPi conducted the phylogenetic analysis. ON, MPa and MPi performed biological experiments. ON, VP, JN and MPi analysed the contents of the genome. ON wrote the manuscript. MPi, PL and MPa contributed to writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pérombelon MCM. Potato diseases caused by soft rot erwinias: an overview of pathogenesis. Plant Pathol. 2002;51:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.0032-0862.2001.Shorttitle.doc.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czajkowski R, Pérombelon MCM, van Veen JA, van der Wolf JM. Control of blackleg and tuber soft rot of potato caused by Pectobacterium and Dickeya species: a review. Plant Pathol. 2011;60:999–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2011.02470.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidsson PR, Kariola T, Niemi O, Palva ET. Pathogenicity of and plant immunity to soft rot pectobacteria. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:191. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toth IK, Bell KS, Holeva MC, Birch PRJ. Soft rot erwiniae: from genes to genomes. Mol Plant Pathol. 2003;4:17–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saarilahti HT, Palva ET. Major outer membrane proteins in the phytopathogenic bacteria Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora and subsp. atroseptica. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1986;35:267–270. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rantakari A, Virtaharju O, Vähämiko S, Taira S, Palva ET, Saarilahti HT, et al. Type III secretion contributes to the pathogenesis of the soft-rot pathogen Erwinia carotovora: partial characterization of the hrp gene cluster. Mol PlantMicrobe Interact. 2001;14:962–968. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.8.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Brader G, Palva ET. The WRKY70 transcription factor: a node of convergence for Jasmonate-mediated and Salicylate-mediated signals in plant defense. Plant Cell. 2004;16:319–331. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brader G, Sjöblom S, Hyytiäinen H, Sims-Huopaniemi K, Palva ET. Altering substrate chain length specificity of an acylhomoserine lactone synthase in bacterial communication. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10403–10409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kariola T, Brader G, Li J, Palva ET. Chlorophyllase 1, a damage control enzyme, affects the balance between defense pathways in plants. Plant Cell. 2005;17:282–294. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kariola T, Brader G, Helenius E, Li J, Heino P, Palva ET. EARLY RESPONSIVE TO DEHYDRATION 15, a negative regulator of Abscisic acid responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:1559–1573. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon SJ, Jin HC, Lee S, Nam MH, Chung JH, Kwon SI, et al. GDSL lipase-like 1 regulates systemic resistance associated with ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;58:235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Po-Wen C, Singh P, Zimmerli L. Priming of the Arabidopsis pattern-triggered immunity response upon infection by necrotrophic Pectobacterium carotovorum bacteria. Mol Plant Pathol. 2013;14:58–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh P, Kuo Y-C, Mishra S, Tsai C-H, Chien C-C, Chen C-W, et al. The Lectin receptor Kinase-VI.2 is required for priming and positively regulates Arabidopsis pattern-triggered immunity. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1256–1270. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.095778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasanen M, Laurila J, Brader G, Palva ET, Ahola V, van der Wolf J, et al. Characterisation of Pectobacterium wasabiae and Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum isolates from diseased potato plants in Finland. Ann Appl Biol. 2013;163:403–419. doi: 10.1111/aab.12076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Fan Q, Loria R. A re-evaluation of the taxonomy of phytopathogenic genera Dickeya and Pectobacterium using whole-genome sequencing data. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2016;39:252–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hyatt D, Chen G-L, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pati A, Ivanova NN, Mikhailova N, Ovchinnikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, et al. GenePRIMP: a gene prediction improvement pipeline for prokaryotic genomes. Nat Methods. 2010;7:455–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koskinen P, Törönen P, Nokso-Koivisto J, Holm L. PANNZER: high-throughput functional annotation of uncharacterized proteins in an error-prone environment. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1544–1552. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchler-Bauer A, Lu S, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, et al. CDD: a conserved domain database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D225–D229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Stærfeldt H-H, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu S, Zhu Z, Fu L, Niu B, Li W. WebMGA: a customizable web server for fast metagenomic sequence analysis. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:444. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Käll L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer ELL. Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction—the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W429–W432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grissa I, Vergnaud G, Pourcel C. CRISPRFinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W52–W57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cesareni G, Helmer-Citterich M, Castagnoli L. Control of ColE1 plasmid replication by antisense RNA. Trends Genet. 1991;7:230–235. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nomura N, Murooka Y. Characterization and sequencing of the region required for replication of a non-selftransmissible plasmid pEC3 isolated from Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. J Ferment Bioeng. 1994;78:250–254. doi: 10.1016/0922-338X(94)90299-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nomura N, Yamashita M, Murooka Y. Genetic organization of a DNA-processing region required for mobilization of a non-self-transmissible plasmid, pEC3, isolated from Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. Gene. 1996;170:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00806-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nykyri J, Niemi O, Koskinen P, Nokso-Koivisto J, Pasanen M, Broberg M, et al. Revised phylogeny and novel horizontally acquired virulence determinants of the model soft rot Phytopathogen Pectobacterium wasabiae SCC3193. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003013. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charkowski A, Blanco C, Condemine G, Expert D, Franza T, Hayes C, et al. The role of secretion systems and small molecules in soft-rot enterobacteriaceae pathogenicity. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2012;50:425–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson TL, Abendroth J, Hol WGJ, Sandkvist M. Type II secretion: from structure to function. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;255:175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laasik E, Põllumaa L, Pasanen M, Mattinen L, Pirhonen M, Mäe A. Expression of nipP.W of Pectobacterium wasabiae is dependent on functional flgKL flagellar genes. Microbiology. 2014;160:179–186. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.071092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehtimäki S, Rantakari A, Routtu J, Tuikkala A, Li J, Virtaharju O, et al. Characterization of the hrp pathogenicity cluster of Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora: high basal level expression in a mutant is associated with reduced virulence. Mol Gen Genomics. 2003;270:263–272. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim H-S, Ma B, Perna NT, Charkowski AO. Phylogeny and virulence of naturally occurring type III secretion system-deficient Pectobacterium strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:4539–4549. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01336-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell KS, Sebaihia M, Pritchard L, Holden MTG, Hyman LJ, Holeva MC, et al. Genome sequence of the enterobacterial phytopathogen Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica and characterization of virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11105–11110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402424101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H, Coulthurst SJ, Pritchard L, Hedley PE, Ravensdale M, Humphris S, et al. Quorum sensing coordinates brute force and stealth modes of infection in the plant pathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000093. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basset A, Khush RS, Braun A, Gardan L, Boccard F, Hoffmann JA, et al. The phytopathogenic bacteria Erwinia carotovora infects drosophila and activates an immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3376–3381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basset A, Tzou P, Lemaitre B, Boccard F. A single gene that promotes interaction of a phytopathogenic bacterium with its insect vector, Drosophila Melanogaster. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:205–209. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katoh K, Asimenos G, Toh H. Multiple alignment of DNA sequences with MAFFT. In: Posada D, editor. Bioinformatics for DNA sequence analysis. New York: Humana Press; 2009. pp. 39–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Posada D. ModelTest server: a web-based tool for the statistical selection of models of nucleotide substitution online. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W700–W703. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grant JR, Stothard P. The CGView server: a comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W181–W184. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:541–547. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria Phyl. Nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Volume 2 (part B) 2. New York: Springer; 2005. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class III. Gammaproteobacteria class. Nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Volume 2 (part B) 2. New York: Springer; 2005. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams KP, Kelly DP. Proposal for a new class within the phylum Proteobacteria, Acidithiobacillia classis nov., with the type order Acidithiobacillales, and emended description of the class Gammaproteobacteria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:2901–2906. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.049270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adeolu M, Alnajar S, Naushad S, Gupta RS. Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: proposal for Enterobacterales ord. Nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. Nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. Nov., Yersiniaceae fam. Nov., Hafniaceae fam. Nov., Morganellaceae fam. Nov., and Budviciaceae fam. Nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:5575–5599. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waldee EL. Comparative studies of some peritrichous phytopathogenic bacteria. Iowa state Coll. J Sci. 1945;19:435–484. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hauben L, Moore ER, Vauterin L, Steenackers M, Mergaert J, Verdonck L, et al. Phylogenetic position of phytopathogens within the Enterobacteriaceae. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1998;21:384–397. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(98)80048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gardan L, Gouy C, Christen R, Samson R. Elevation of three subspecies of Pectobacterium carotovorum to species level: Pectobacterium atrosepticum sp. nov., Pectobacterium betavasculorum sp. nov. and Pectobacterium wasabiae sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:381–391. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02423-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]