Abstract

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Continuing Pharmacy Education (CPE) Provider Accreditation Program has been in existence for 40 years. During this time, the program has expanded and has been offered to a various types of providers, not only academic-based providers. ACPE credit has been offered to an increasing number of pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and other health professionals. This paper explains the evolution of the CPE Provider Accreditation Program, including the Definition of Continuing Education for the Profession of Pharmacy, its standards, types of activities (knowledge, application, and practice), CPE Monitor, Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education, and Continuing Professional Development (CPD).

Keywords: continuing pharmacy education, interprofessional continuing education, continuing professional development, Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE)

INTRODUCTION

In 1975, the pharmacy profession charged the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (previously known as the American Council on Pharmaceutical Education) (ACPE) to develop national quality standards for continuing pharmacy education (CPE). What led up to this request was, in 1965, Florida was the first state that required continuing education (CE) for re-licensure for pharmacists. The types of CE offerings varied in time and quality. Thus, in the early 1970s, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) and the American Pharmaceutical Association (now American Pharmacists Association; APhA) Task Force on Continuing Competence in Pharmacy deliberated and reported on its assessment of the continuing education needs of the pharmacy profession.1 The Task Force stated, “Each individual practitioner should be obliged to comply with standards of competence, developed nationally by the profession, and accepted, supported and enforced by each state through requirements for relicensure.” Competence was defined as “The ability to accomplish an essential performance characteristic in a satisfactory manner.”

In 1974, the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) passed a resolution supporting mandatory continuing education for relicensure. That same year, APhA requested ACPE to develop a system of quality assurance of pharmacy continuing education. A year later, ACPE expanded its quality assurance activities from accreditation of degree programs in pharmacy (initiated in 1932) to “approval” (changed to “accreditation” in 2002) of providers of continuing pharmacy education based on standards. The Continuing Education Unit (CEU) prepared by a national task force from many academic settings was selected as the basis of measurement for individual attainment of statements of credit for relicensure.

The first ACPE-approved providers were primarily academic- and professional association-based.2,3 More and more states began to require CPE for relicensure. Today all states and territories require CPE for relicensure. The initial CPE standards were primarily process driven and remained in use until 2009 when new standards (Standards for Continuing Pharmacy Education) focused on important aspects of provider contributions to quality continuing education.4

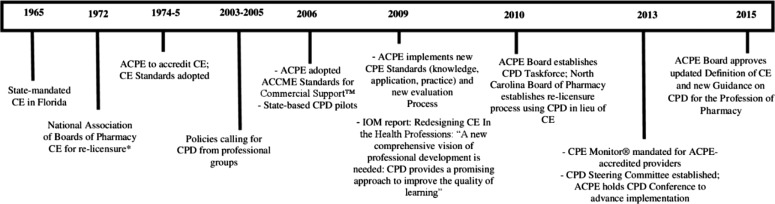

This paper will attempt to review the evolution (Figure 1) of accredited continuing education and its learners and discuss its challenges and opportunities for the future.

Figure 1.

Evolution of Continuing Pharmacy Education and Continuing Professional Development in the United States.

Definition of Continuing Education for the Profession of Pharmacy

Throughout the years, there were activities called CE that pharmacists and pharmacy technicians attended but the depth and breadth of content presented was not necessarily applicable to both pharmacists and technicians. In 2006, ACPE-accredited providers and state boards of pharmacy requested ACPE to revisit the definition of continuing education and to distinguish continuing education (CE) offerings designed for pharmacists from CE offerings designed for pharmacy technicians. ACPE drafted a revised Definition for Continuing Education for the Profession of Pharmacy5 (Definition). CE was defined as: “a structured educational activity designed or intended to support the continuing development of pharmacists and/or pharmacy technicians to maintain and enhance their competence. Continuing pharmacy education (CPE) should promote problem-solving and critical thinking and be applicable to the practice of pharmacy.”

The Definition indicated that the pharmacist competencies as developed by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy’s Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes6 and the specific pharmacy technician knowledge statements developed by the Pharmacy Technician Certification Board (PTCB)7 should serve as a guide to ACPE-accredited providers to generate content for CE activities that are applicable to the professional development of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. This definition better defines continuing pharmacy education (CPE), includes pharmacy technicians, describes the professional competencies identified for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, and explains the responsibilities of providers of continuing pharmacy education.

State Board of Pharmacy Continuing Education Requirements

Today, all US states and territories have legislation mandating pharmacy continuing education for relicensure of pharmacists.8 Over the years, their requirements have changed to include acceptance of continuing medical education and/or, continuing nursing education credits, specification of a certain number of live and home study credit hours, and specific topic requirements, (eg, HIV, law, consulting, medication errors, immunization, compounding).

The career path for pharmacy technicians has evolved in the past decade. Pharmacy technicians may gain their education from pharmacy technician training programs. As of 2017, there were 262 ASHP-ACPE accredited technician training programs available.9 Currently, pharmacy technicians must retain their registration or license from 43 individual boards of pharmacy. CE requirements for pharmacy technicians are evolving. As of 2015, there were 21 states that require CE for pharmacy technician renewal of registration and/or licensure. Certification is optional and is typically dependent on employer and/or state board of pharmacy requirements. To renew certification (every two years), CPhTs are required to complete CE. To qualify for PTCB recertification, CPhTs must complete 20 hours of pharmacy technician-specific CE that includes one hour of patient safety CE. In 2016, PTCB announced the requirement that by 2020, each new candidate for certification must complete an ASHP/ACPE-accredited pharmacy technician program. However, PTCB has rescinded this requirement upon further recommendations from the profession and the 2017 Pharmacy Technician Stakeholder Consensus Conference.10

Standards for Continuing Pharmacy Education

After more than 30 years in existence, the title of our quality assurance standards changed from ACPE Criteria for Quality and Interpretive Guidelines to ACPE Standards for Continuing Pharmacy Education for clarity and organizational consistency.11 The philosophy and emphasis were designed to facilitate the continuum of learning as defined in Standards 2007: Accreditation Standards for Professional Degree Programs in Pharmacy.8 Standards 2007 emphasized the foundation needed for development of the student as a lifelong learner and the Standards for Continuing Pharmacy Education provide a structure as students make the transition to practicing pharmacists. The Standards are organized in four sections: content, delivery, assessment, and evaluation. The Standards emphasize that pharmacists and pharmacy technicians should: identify their individual educational needs in order to narrow knowledge, skill, or practice gap(s); pursue educational activities that will produce and sustain more effective professional practice in order to improve practice, patient, and population health care outcomes; link knowledge, skills, and attitudes learned to their application of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in practice; continue self-directed learning throughout the progression of their careers; continue to participate in knowledge-based activity type and to strive toward application- and practice-based type activities; and engage in activities that are fair, balanced, free from commercial bias and conducted independently without any commercial influence (Standards for Commercial Support).

Standards for Commercial Support

In the early 2000s, several federal and organizational guidance documents were released to address real and perceived conflicts between the pharmaceutical industry and health care professionals, including the Office of Inspector General’s 2003 Compliance Program Guidance for Pharmaceutical Manufacturers12 which informed the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education’s (ACCME) Updated Standards for Commercial Support, October 2004.13 Existing guidance documents contributed to ACPE's decision to discontinue the eligibility of drug and device manufacturers to be accredited providers of continuing pharmacy education in 2005, resulting in the discontinuation of approximately 30 providers. Soon after, ACPE adopted ACCME’s Standards for Commercial Support which went into effect January 1, 2008, following a 15-month transition period. As with all CPE standards, ACPE continues to monitor provider performance against the Standards for Commercial Support, providing education and guidance as needed, and collaborating with other accrediting bodies around independence in continuing education for the health professions.

ACPE CPE Enterprise

Growth of ACPE-Accredited Providers

ACPE initially recognized 72 academic providers in 1978 and now accredits 356 providers of continuing pharmacy education (ACPE recognized a maximum of 410 providers in 2005),14 which include colleges and schools of pharmacy (24%); local, state, national pharmacy and other health care profession associations (22%); publishers and government agencies (5%); educational companies (18%); hospitals and health systems (22%); and others (9%). There has been a general trend upward for all types of ACPE-accredited providers. Surprisingly, although the original task force indicated that all colleges and schools of pharmacy should be ACPE-accredited providers, only 64% of colleges and schools of pharmacy are providers today.

Most of the providers are located on the East Coast, and many are in Texas and Florida in the south, and California in the west. Many of the states in the Midwest and Northwest only have one to three providers per state.

CPE Activities and Learners

At the beginning of this accreditation process, the term “program” was used to designate a specific CE offering and/or one’s collection of offerings. As the CE enterprise expanded and became more related with medicine and nursing, ACPE adjusted its terminology to be more in line with other accreditation agencies. “Program” is defined as the overall CPE activities of an accredited provider. An “activity” is an educational event which is based upon identified needs, has a purpose or objective, and is evaluated to ensure the needs are met. An activity is designed to support the continuing professional development of pharmacists and/or pharmacy technicians to maintain and enhance their competence. Each CPE activity should promote problem-solving and critical thinking while being applicable to the practice of pharmacy as defined by the current Definition of Continuing Pharmacy Education. The CPE activities should be designed according to the appropriate roles and responsibilities of the pharmacist and/or pharmacy technician.

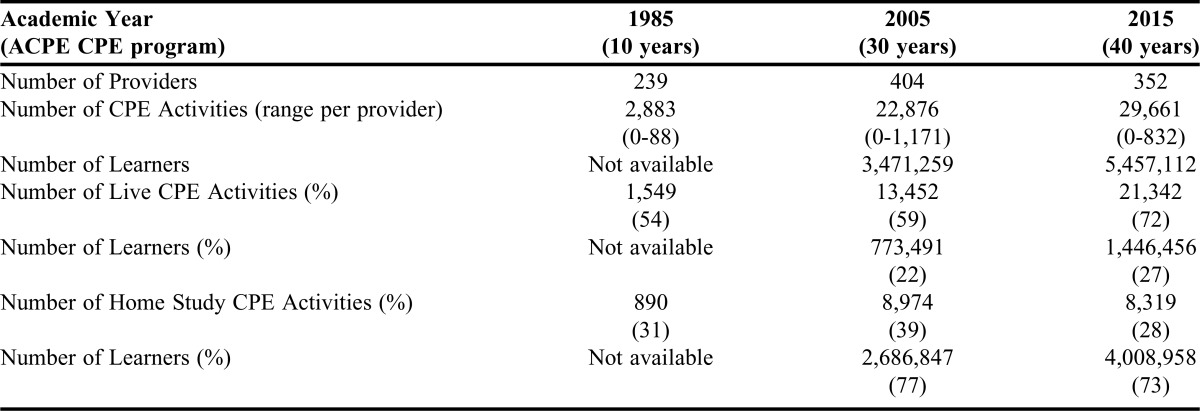

The number of CPE activities has exponentially increased over the years (Table 1). Live CE activities have always outnumbered the home study CPE activities. In recent years, this may be attributed to the additional formats available via the Internet, ie, webcasts. All provider types conduct both live and home study activities with only the publishers conducting more home study activities than live activities.

Table 1.

Number of CE Activities and Learners

The number of participants engaged in CPE activities has increased over the years. Learners have received most of their CPE credit taking home study CE activities. This may be due to the convenience, abundance and accessibility of Internet-based activities. Over the last 10 years the number of learners has increased due to the increased need for pharmacy technician CE, increased number of pharmacy graduates, and increased interprofessional education opportunities.

Evolution of Types of Activities

Historically, CE activities were known as “live” or “home study.” A live CE activity was known as an activity in which there is real-time interaction with the speaker or faculty. A home study CE activity is referred to as a course or journal article that the learner does not have real-time interaction with the author. Although this designation is still used today, the profession requested a more defined categorization of CE activities based on what the CE activity intends to do.

Beginning in 2008, CPE activities are categorized into three types: knowledge, application, and practice.4 A knowledge-based CPE activity (minimum 15 minutes) is primarily constructed to transmit knowledge (ie, facts). Informing health care professionals about the Ebola virus, specifically by detecting cases, or preventing transmission of infection, or safely managing patients with the virus, would be an example of a knowledge-based activity.

An application-based CPE activity (minimum of 60 minutes) is designed to apply the information learned in the timeframe allotted. An example may include informing learners of the facts and then providing a case(s) to learners regarding the selection of an anti-hypertensive agent in a diabetic patient. Practice-based CPE activity (previously named Certificate Programs in Pharmacy) are constructed to instill, expand, or enhance practice competencies through the systematic achievement of specified knowledge, skills, attitudes, and performance behaviors. The format of these CPE activities includes a minimum of 15 hours of a didactic component (live and/or home study) and a practice experience component (designed to evaluate the skill or application). The provider employs an instructional design that is rationally sequenced, curricular based, and supportive of achievement of the stated professional competencies. An example of this type of activity is developing an immunization program in a pharmacy. The didactic component may be in the classroom or a home study activity regarding the study of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s immunization guidelines. The practice component may be a hands-on component of the learner mastering the skill of immunizing a patient and/or beginning the immunization program in the pharmacy. During the activity, formative and summative assessments are conducted so the learner may receive feedback as he/she progresses in the activity.

Currently, all providers are conducting more knowledge-based activities (88%) than application-based (11%) and practice-based (1%) activities. Consultation with staff and accreditation evaluations encourage providers to move toward the development of application- and practice-based activities. Regulatory and certification bodies have explored these activity types to include as requirements for relicensure and recertification.

Ideally providers are encouraged to guide pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and learners to engage in the best combination of CPE activity types to meet their learning, professional development, and practice needs.

Identification of Activity - Universal Activity Number

Due to the increasing number and variety of CE activities, the state boards of pharmacy indicated a need for a uniform identifier to distinguish CE from ACPE-accredited providers. ACPE identified the Universal Activity Number (UAN) as an identification number that is assigned to each CPE activity developed and sponsored, or joint provided, by an ACPE-accredited provider.15 This number is developed by appending to the ACPE accredited provider identification number (eg, 0197), the joint provider designation number (0000 for no joint provider, 9999 for all joint providers), the year of CPE activity development (eg, 17), the sequential number of the CPE activity from among the new CPE activities developed during that year (eg, 001), the topic designator (eg, 01 - Disease State Management/Drug Therapy, 02 - AIDS Therapy, 03 - Law related to Pharmacy Practice, 04 - General Pharmacy, 05 - Patient Safety), the target audience (eg, P designed for pharmacists and T designed for pharmacy technicians), and format designators (eg, L - live activities, H - home study and other enduring activities, B - home study and live for practice-based activities). The UAN is the identifier that serves as the basis for learners to obtain ACPE credit. A live seminar CE activity related to medication safety that is designed for pharmacists may have a UAN as follows: 0197-0000-17-001-L05-P. A home study CE activity conducted jointly by an ACPE-accredited provider with a state pharmacy association related to pharmacy law that is designed for pharmacy technicians may have a UAN as follows: 0197-0000-17-002-H03-T.

CPE Monitor

ACPE and the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) developed an electronic and paperless continuing pharmacy education (CPE) tracking service, CPE Monitor. CPE Monitor authenticates and stores data for completed CPE units received by pharmacists and pharmacy technicians from ACPE-accredited providers. The service saves state boards of pharmacy, CPE providers, pharmacists, and pharmacy technicians time and cost by streamlining the process of verifying that licensees and registrants meet CPE requirements and by providing a centralized repository for pharmacists’ and pharmacy technicians’ continuing education details.

Providers no longer need to provide electronic or printed statements of credit to their pharmacist and pharmacy technician participants. Instead, once information is received by NABP, the tracking system will make CPE data for each participant available to the state boards of pharmacy where the participant is licensed or registered. To date, over 350,000 pharmacists and 240,000 pharmacy technicians completed an e-profile and 380 ACPE-accredited providers uploaded approximately 25 million records into CPE Monitor.

Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education

In 1998, the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), ACPE and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) began the process of aligning the three accrediting systems to create a unified “joint accreditation” process for organizations that develop education for the health care team (www.jointaccreditation.org).16 The goals of this joint accreditation are to support interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP) through interprofessional continuing education (IPCE), and simultaneously, to streamline the accreditation processes. Interprofessional education (IPE) is designed to address the professional practice gaps of the health care team using an educational planning process that reflects input from those health care professionals who make up the team. The education is designed to change the skills/strategy, performance, or patient outcomes of the health care team. In March 2009, specific joint accreditation criteria, eligibility information and process steps for joint accreditation were released. The ACCME, ACPE and ANCC began making Joint Accreditation decisions in July 2010. Now, these criteria and processes have been updated to reflect the experiences of the providers and the accreditors, and to be more aligned with other stakeholders of IPCP. At the time of this printing, there are more than 50 jointly accredited providers.

In May 2016, a Joint Accreditation Leadership Summit brought together education leaders from more than 24 organizations across the country, from Hawaii to New York. Participants representing hospitals, health systems, medical schools, specialty societies, education companies, and government agencies shared strategies for advancing health care education, by the team for the team. The Leadership Summit, report, and videos conducted were partly supported by the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation.17

This summit revealed how interprofessional continuing education (IPCE) contributes to improving health care team collaboration and patient care. The report entitled, “By the Team for the Team: Evolving Interprofessional Continuing Education for Optimal Patient Care – Report from the 2016 Joint Accreditation Leadership Summit,” includes best practices, challenges, case examples, key recommendations, and data about the value and impact of IPCE.

Evidence that CE is Effective

One of the biggest challenges ACPE-accredited providers still face is the question “Is CE effective?” Many studies have shown CE is effective. Robertson and colleagues examined whether research supports the effectiveness of continuing education and, if so, for what outcomes.18 They found that the literature provides evidence that, in controlled studies, continuing education has been shown to support improvement in practitioner knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors, as well as in patient health outcomes. They also examined the effectiveness of various kinds of continuing education and found that continuing education is most relevant when it is ongoing, interactive, contextually relevant, and based on needs assessment. Cervero and Gaines also looked into numerous reviews and found similar results.19 Instead of asking whether CE is effective, we should be asking how an individual can use CE and how is CE best applied.

Continuing Professional Development (CPD)

While accredited CPE has been the means by which pharmacists have maintained and enhanced their professional competency for more than 40 years as recommended in the 1975 AACP/APhA Task Force on Continuing Competence in Pharmacy report, discussion and study of continuing professional development (CPD) as an approach to foster and support lifelong learning and competence has been underway within the profession for approximately 20 years. Early efforts included a recommendation of the 1994-95 AACP Professional Affairs Committee that urged colleges and schools of pharmacy to replace existing approaches to “continuing pharmacy education” with a system of career-long “continuing competency contracts.”20 Starting in the early 2000s, CPD-related statements and policies were adopted by a number of national and state pharmacy organizations, including the NABP, AACP, ACPE, ASHP, APhA, and the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP).21-26 U.S. policies advocated exploration and implementation of CPD concepts as well as development of CPD tools and resources to support self-directed lifelong learning.

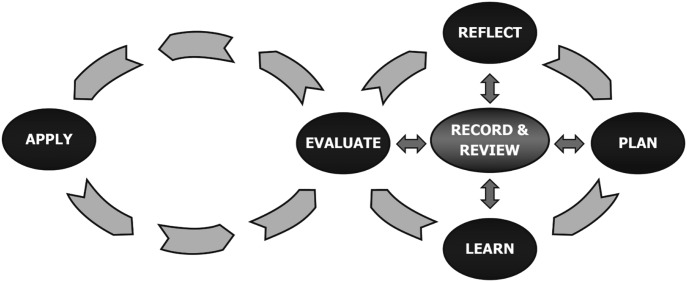

In line with its mission to ensure and advance quality in pharmacy education, ACPE has been the lead organization in advocating for CPD adoption and implementation. It has been ACPE’s position that the CPD approach provide the opportunity for quality improvement of the current system of continuing education, building on the existing foundation of quality-assured, accredited continuing pharmacy education. ACPE defines CPD as a self-directed, ongoing, systematic and outcomes-focused approach to lifelong learning that is applied to practice. It involves the process of active participation in formal and informal learning activities that assist in developing and maintaining competency, enhancing professional practice, and supporting achievement of career goals.27 The CPD approach is cyclical in nature where each stage of the process can be recorded in a personal learning portfolio (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Continuing Professional Development Cycle.

Central to the CPD approach is linking learning to practice where the learner’s educational outcomes are aligned with patient and organizational outcomes. This important component was an expectation of continuing education as part of the 1975 Task Force Report and is consistent with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions, which states a major attribute of the CPD approach is the emphasis on stretching learning beyond the classroom to the point of care.28

In 2010, the ACPE CPD Task Force was established to serve in an advisory capacity to the ACPE CPE Commission and ACPE Board of Directors on matters relating to the CPD approach to lifelong learning. The task force transitioned to the CPD Steering Committee in July 2013 with the intent of developing strategic partnerships to advance the concepts of CPD. Two overarching goals have guided the work of the committee: facilitate profession-wide implementation of CPD through education, awareness, and resources; and promote research with the CPD model and its ability to improve the process and outcomes of self-directed lifelong learning. Since its inception, the committee has been involved in educational outreach, authoring/reviewing numerous CPD-related publications, and developing CPD resources and tools. Additionally, the committee has participated in and/or supported implementation studies that have demonstrated the use of CPD to support lifelong learning and professional development needs,29 improved perceptions of pharmacy practice and sustained confidence in the ability to identify learning needs and utilization of CPD concepts,30,31 and greater likelihood to identify strengths and weaknesses through self-assessment, development of SMART goals, and participation in activities selected to achieve predetermined objectives.32,33

To guide future initiatives, the CPD Steering Committee conducted a survey of boards of pharmacy in 2011 to assess perspectives and approaches of pharmacist lifelong learning models.34 Survey responses indicated strengths in the CPD approach from an educational and learning perspective but regulators’ perspectives raised uncertainties about implementation and outcomes. To date, three states have piloted and/or integrated CPD in lieu of traditional hours-based CE as an option for license renewal: North Carolina, Iowa, and New Mexico.

In January 2015, ACPE released the Guidance on Continuing Professional Development for the Profession of Pharmacy, which described the components of CPD and offered categories and examples of learning activities that can contribute to the development of pharmacy professionals.35 Learning activities are divided into six categories: continuing education, academic/professional study, scholarly activities, teaching/precepting, workplace activities, and professional/community service. Key messages of the guidance document include: CPE is an integral and essential component of CPD; the CPD approach allows for flexibility to engage in learning activities that are most beneficial to one’s practice; the breadth of learning activities chosen should meet identified learning objectives and collectively address the competency areas relevant to one’s practice; and self-directed lifelong learning is a competency, requiring knowledge, skills, attitudes and values.

While a greater understanding of the importance of self-directed lifelong learning is developing within the profession along with initial implementation efforts at academic, employer, and regulatory levels, further progress is needed to move beyond the early adopters toward acceptance and integration into practice by the majority. To that end, continued study of developments in CPD in other countries as well as its place in the U.S. is needed.

Successes and Challenges for ACPE-Accredited Providers and Learners

ACPE-accredited providers have endured many successes and challenges. Successes include increased collaboration among providers, companies, and vendors for the development of quality education. CE organizations have increased resources and efficiencies. As such, over the years, the number of CE activities and the types of educational formats have increased and are more easily accessible to pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. Moreover, the development of CPE Monitor allows for the pharmacy profession to inquire and report in aggregate the CE habits of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. For learners, CPE Monitor serves as a one-place repository for all their CE activities.

Twenty years ago, CPE units were staffed by one person. Over the years, the units have evolved to teams of CE staff working collectively to plan and conduct CPE activities. The roles and responsibilities of the CPE administrator (team) have evolved. ACPE has adopted the Alliance for CE in the Health Professions (Alliance) competencies36 to assist CPE units to identify individuals and teams to effectively manage and lead the CPE units. CPE professionals plan CPE activities by identifying professional practice gaps with the goal to narrow or rid the gap for a better health care system and ultimately, better patient outcomes.

The changing economic environment is also a challenge for the CPE units. Colleges and schools of pharmacy share resources with their respective state pharmacy associations to consolidate to one ACPE-accredited provider, multitude of hospitals have consolidated under one health care network, and with the dwindling amount of commercial support over the years, the funds available for quality staff to conduct quality programming have decreased. Providers are hesitant to charge or increase fees for participation in CE activities for fear of losing learners and/or members and/or alum to providers who do not charge a fee. Providers are trying to find alternative means. For example, colleges and schools of pharmacy are recruiting or retaining preceptors by providing increased opportunities to engage in professional development opportunities.

Learners are challenged to move from a culture of meeting an hour requirement for relicensure or recertification to becoming self-directed learners and have that learning maintain and enhance their practice. Learners turn to their state boards for approval of courses for CE, specifically in states where pharmacists and pharmacy technicians are located in rural geographic locations. The state boards of pharmacy approval across the states are not very consistent in their procedures and thus the quality of the CPE suffers.

Moreover, the application of technology has caused a divide in learners. In general, millennial learners will not sit through a 1-hour lecture while “seasoned” pharmacists look for that type of educational format. The millennials look for active learning activities and for the “click of a button” while “seasoned” learners would rather network with one another.

CONCLUSION

The CE world is changing as is the role of the pharmacist and pharmacy technician. Today's health care environment is rapidly changing with greater societal needs, expectations, and calls for greater accountability within the health professions and their employers for ensuring competency of its practitioners. What will the next 40 years hold?

What will be the educational needs and/or practice gaps of the pharmacist and pharmacy technician in the future? Will practitioners identify them through a CPD process? What role will technology play? And who will regulate the CE and/or CPD process?

Those are just some questions to think about…let’s begin on the next journey.

Footnotes

The first pass through the CPD cycle results in evaluation of learning; the second is evaluation of outcomes and impact of learning.

REFERENCES

- 1.AACP/APhA Task Force on Continuing Competence in Pharmacy. The continuing competence of pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1975;15(8):432–457. doi: 10.1016/s0003-0465(15)32103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shannon MC. A national survey of pharmacy continuing education programs offered in 1980. Am J Pharm Educ. 1982;46(2):119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shannon MC, Schnobrich K. A descriptive analysis of pharmacy continuing education offerings offered by ACPE-approved providers in 1989. Am J Pharm Educ. 1991;55:317–321. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards for Continuing Pharmacy Education. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/CPE_Standards_Final.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 5.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Definition of Continuing Education for the Profession of Pharmacy. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/DefinitionContinuingEducationProfession%20Pharmacy2015.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2016.

- 6.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) educational outcomes 2013. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8) doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. Article 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pharmacy Technician Certification Board. Important updates to the PTCE. https://www.ptcb.org/get-certified/prepare/important-changes#.WEHsGY3rvAg. Accessed December 1, 2016.

- 8.National Association Boards of Pharmacy. 2015. NABP Survey of Pharmacy Law.

- 9.Pharmacy Technician Accreditation Commission. Technician Accreditation. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pharmacy-technician-education-accreditation-collaboration. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 10.Pharmacy Technician Certification Board. Certification program changes. http://www.ptcb.org/about-ptcb/crest-initiative#.V2hs1zHrsn0. Accessed June 1, 2016.

- 11.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree standards. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf . Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 12.US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. Compliance program guidance for pharmaceutical manufacturers. Federal Register 68, No. 86. 2003:23731–23743. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. ACCME Standards for Commercial Support: Standards to Ensure Independence in CME Activities. http://www.accme.org/sites/default/files/174_20150323_ACCME_Standards_for_Commercial_Support.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2016.

- 14.Travlos DV, Sesti AM, Evans HE, Chung UK, Vlasses PH.Pharmacy’s Continuing Education Enterprise – 2005 Update. Poster presented at American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Annual Meeting 2006. July San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. ACPE Continuing Pharmacy Education Provider Accreditation Program Policies and Procedures Manual: A Guide for ACPE-accredited Providers. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/CPE_Policies_Procedures.pdf . Accessed December 1, 2016.

- 16.Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education. http://www.jointaccreditation.org . Accessed June 1, 2016.

- 17.Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education. By the Team for the Team: Evolving Interprofessional Continuing Education for Optimal Patient Care – Report from the 2016 Joint Accreditation Leadership Summit. http://www.jointaccreditation.org/sites/default/files/2016_Joint_Accreditation_Leadership_Summit_Report_0.pdf . Accessed December 1, 2016.

- 18.Robertson MK, Umble KE, Cervero RM. Impact studies in continuing education for health professions: update. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23(3):146–156. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340230305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cervero R, Gaines JK. Effectiveness of continuing medical education: updated synthesis of systematic reviews. Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. July 2014.

- 20. Argus Commission: Roche VF, Nahata MC, et al. Roadmap to 2015: preparing competent pharmacists and pharmacy faculty for the future. Combined Report of the 2005-06 Argus Commission and the Academic Affairs, Professional Affairs, and Research and Graduate Affairs Committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(Suppl):S5.

- 21.National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Resolution 99-7-03. https://nabp.pharmacy/continuing-pharmacy-practice-competency-resolution-no-99-7-03/. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 22.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. House of Delegates Resolution, 2003. http://www.ajpe.org/doi/full/10.5688/aj6704S12. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 23.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Statement on Continuing Professional Development. 2003. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/CPDGuidance%20ProfessionPharmacyJan2015.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 24.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/policy-guidelines/docs/browse-by-document-type-policy-positions-1982-2017-with-rationales-pdf.ashx?la=en&hash=67A2096B82EAF85FAA7491CF83E9A6B12D212578 . Accessed November 1, 2017.

- 25.American Pharmacists Association. 2005 APhA Policy Committee: Continuing Professional Development. https://www.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/HOD_APhA_Policy_Manual_0.pdf . Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 26.The Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. An Action Plan for Implementation of the JCPP Future Vision of Pharmacy Practice January 2008. https://jcpp.net/resourcecat/jcpp-vision-for-pharmacists-practice/ . Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 27.Rouse MJ. Continuing professional development in pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2004;44(4):517–520. doi: 10.1331/1544345041475634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Institute of Medicine Committee on Planning a Continuing Health Professional Education Institute. Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions. Washington, DC: National Academies Press: 2009.

- 29.Dopp AL, Moulton JR, Rouse MJ, Trewet CLB. A five-state continuing professional development pilot program for practicing pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(2) doi: 10.5688/aj740228. Article 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McConnell KJ, Newlon CL, Delate T. The impact of continuing professional development versus traditional continuing pharmacy education on pharmacy practice. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(10):1585–1595. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McConnell KJ, Delate T, Newlon CL. The sustainability of improvements from continuing professional development in pharmacy practice and learning behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(3) doi: 10.5688/ajpe79336. Article 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tofade T, Chou S, Foushee L, Caiola SM, Eckel S. Continuing professional development training program among pharmacist preceptors and non-preceptors. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2010;50(6):730–735. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janke KK. Continuing professional development: don’t miss the obvious. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(2) doi: 10.5688/aj740231. Article 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baumgartner JL, Rouse MJ, Kondic AM. ACPE Survey of US Board of Pharmacy Members on CPD Models for Lifelong Learning. Poster presented at 10th International Conference on Life Long Learning in Pharmacy, June 2-5, 2014, Orlando, FL.

- 35. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (2015). Guidance on Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for the Profession of Pharmacy. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/CPDGuidance%20ProfessionPharmacyJan2015.pdf.

- 36.Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions. National Learning Competencies. http://www.acehp.org/p/cm/ld/fid=15 . Accessed June 1, 2016.