Abstract

Oxidation of methanethiol (MT) is a significant step in the sulfur cycle. MT is an intermediate of metabolism of globally significant organosulfur compounds including dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) and dimethylsulfide (DMS), which have key roles in marine carbon and sulfur cycling. In aerobic bacteria, MT is degraded by a MT oxidase (MTO). The enzymatic and genetic basis of MT oxidation have remained poorly characterized. Here, we identify for the first time the MTO enzyme and its encoding gene (mtoX) in the DMS-degrading bacterium Hyphomicrobium sp. VS. We show that MTO is a homotetrameric metalloenzyme that requires Cu for enzyme activity. MTO is predicted to be a soluble periplasmic enzyme and a member of a distinct clade of the Selenium-binding protein (SBP56) family for which no function has been reported. Genes orthologous to mtoX exist in many bacteria able to degrade DMS, other one-carbon compounds or DMSP, notably in the marine model organism Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3, a member of the Rhodobacteraceae family that is abundant in marine environments. Marker exchange mutagenesis of mtoX disrupted the ability of R. pomeroyi to metabolize MT confirming its function in this DMSP-degrading bacterium. In R. pomeroyi, transcription of mtoX was enhanced by DMSP, methylmercaptopropionate and MT. Rates of MT degradation increased after pre-incubation of the wild-type strain with MT. The detection of mtoX orthologs in diverse bacteria, environmental samples and its abundance in a range of metagenomic data sets point to this enzyme being widely distributed in the environment and having a key role in global sulfur cycling.

Introduction

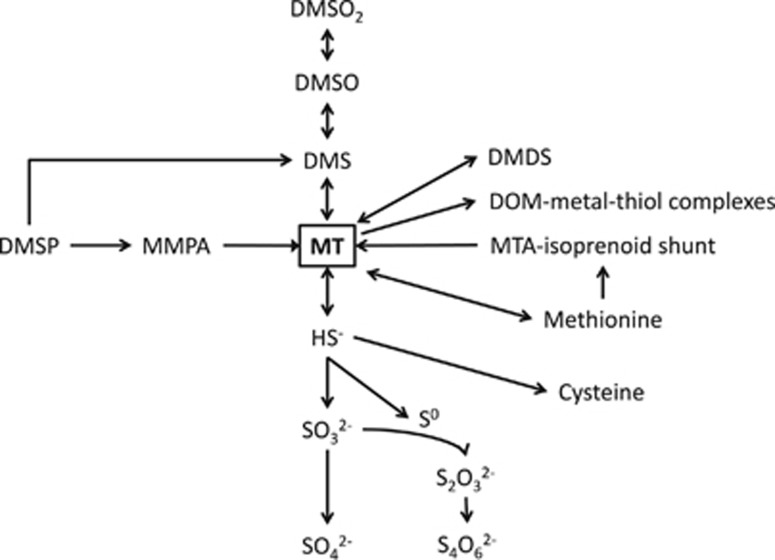

Methanethiol (CH3SH; methylmercaptan, MT) is a foul-smelling gas with a low odor threshold. As a malodorous compound that can be detected by the human nose at very low concentration (odor threshold 1–2 p.p.b., (Devos et al., 1990)), it has a significant role in causing off-flavors in foods and beverages and it is one of the main volatile sulfur compounds causing halitosis in humans (Awano et al., 2004; Tangerman and Winkel, 2007). The production and degradation of MT are major steps in the biogeochemical cycle of sulfur (Figure 1). Sources of MT include the methylation of sulfide in anoxic habitats, demethiolation of sulfhydryl groups and degradation of sulfur-containing amino acids (Lomans et al., 2001, 2002; Bentley and Chasteen, 2004). MT is produced in the marine environment as an intermediate of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) degradation by the demethylation pathway. In this pathway, initial demethylation of DMSP to methylmercaptopropionic acid (MMPA) is carried out by the DMSP-dependent demethylase (DmdA) (Howard et al., 2006). Subsequent degradation of MMPA occurs via MMPA-CoA to methylthioacryloyl-CoA and then to acetaldehyde and MT by the enzymes DmdB, DmdC and DmdD, respectively (Reisch et al., 2011b). MT is also produced as an intermediate of dimethylsulfide (DMS) degradation (Lomans et al., 1999a, 2002; Bentley and Chasteen, 2004; Schäfer et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

Simplified schematic showing the role of MT as an intermediate in the metabolism of sulfur compounds. A single arrow does not imply a single biotransformation step. DMDS, dimethyldisulfide; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; DMSO2, dimethylsulfone; DOM, dissolved organic matter; HS−, sulfide ion; MTA, 5′-methylthioadenosine; SO32−, sulfite ion; S0, elemental sulfur; S2O32−, thiosulfate; S4O62−, tetrathionate; SO42−, sulfate.

Only few measurements of MT in the environment have been reported. Analysis of volatile sulfur compounds in freshwater ditches demonstrated that MT was the dominant volatile organic sulfur compound reaching concentrations of 3–76 nm in sediments and 1–8 nm in surface freshwater (Lomans et al., 1997). Measurements of MT concentrations in the surface ocean water are scarce. Studies reporting MT measurements in seawater suggest a typical range of ~0.02–2 nm (Ulshöfer et al., 1996; Kettle et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2001).

Microbial uptake and degradation of MT are important sinks for MT. Despite low MT concentrations in seawater, radiotracer experiments showed that trace levels of MT (0.5 nm) were rapidly taken up and incorporated into biomass by marine bacterioplankton (Kiene et al., 1999). Besides this assimilation, MT degradation through its utilization as a carbon and energy source in methanogenic archaea, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and aerobic bacteria (Lomans et al., 1999b, 2001, 2002; Schäfer et al., 2010) and its methylation to DMS by the recently described methyltransferase MddA (MddA: methanethiol-dependent DMS) (Carrión et al., 2015) contribute to biological MT removal.

The molecular basis of MT degradation remains poorly understood. In aerobic sulfur-oxidizing and methylotrophic bacteria including strains of Thiobacillus (Gould and Kanagawa, 1992; Lee et al., 2002), Rhodococcus (Kim et al., 2000) and Hyphomicrobium (Suylen et al., 1987), MT is degraded by a MT oxidase (MTO) to formaldehyde, hydrogen sulfide and hydrogen peroxide; however, inconsistent data have emerged from these studies. Estimated molecular weights of MTOs characterized previously have ranged from ~29–61 kDa. The MTO from Hyphomicrobium sp. EG was reported to be a monomer of 40–50 kDa that was insensitive to metal-chelating agents (Suylen et al., 1987). In Thiobacillus thioparus (Gould and Kanagawa, 1992), MTO also appeared to be a monomer with a molecular weight of ~40 kDa; however, a later study of MTO in T. thioparus reported a different molecular weight for MTO of 61 kDa (Lee et al., 2002). MTO from Rhodococcus rhodochrous was reported to have a molecular weight of 64.5 kDa (Kim et al., 2000). The genetic basis of MT degradation has not been identified, constituting a gap in fundamental knowledge of a key step in the global sulfur cycle.

Here, we report new insights into the biochemistry, genetics and environmental distribution of methanethiol oxidases in bacteria. We purified and characterized MTO from Hyphomicrobium sp. VS a DMS-degrading methylotrophic bacterium that was isolated from activated sewage sludge and which has MTO activity during growth on DMS as a sole carbon and energy source (Pol et al., 1994). We identified the gene encoding MTO, mtoX, in Hyphomicrobium sp. VS and detected orthologous mtoX genes in a wide range of bacteria including methylotrophic, sulfur-oxidizing and DMSP-degrading bacteria. We then genetically analyzed its function and transcriptional regulation in a model isolate of the Rhodobacteraceae family, Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3, which produces MT during degradation of DMSP by the demethylation pathway (Reisch et al., 2011a). The development of mtoX-specific PCR primers allowed testing environmental samples for the presence of mtoX-containing populations. This analysis suggested that the genetic potential of MT degradation is present in a wider spectrum of phylogenetic lineages than previously realized based on bacterial cultures. This was also reflected by the presence of mtoX genes from uncultivated organisms in diverse habitats based on screening of metagenomic data sets, which suggests that MTO is widely distributed in the biosphere.

Materials and methods

Growth of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS

Hyphomicrobium sp. VS was grown in continuous culture in a Fermac 300 series fermenter (Electrolabs, Tewkesbury, UK) as described previously (Boden et al., 2011) using PV mineral medium using either DMS (12 mm) as sole substrate or in combination with methanol (both substrates 12 mm). The culture was held at 30 °C, aerated with sterile air at 1.5 l/min, and stirred at 200 r.p.m. pH was adjusted to 7.4±0.1 by automatic titration with 1 M NaOH. Hyphomicrobium sp. VS was initially grown for 24 h in a 1 liter volume in sterilized medium supplemented to 25 mm with methanol before beginning the addition of medium containing DMS. Overflow was collected in a vessel held on ice. Cells were collected daily, washed with 25 mm 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid (PIPES, pH 7.2) and resuspended in the same buffer. Concentrated cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Protein purification and characterization

Thawed cells (~1.5 g dry weight) were washed with 25 mm PIPES (pH 7.2), centrifuged at 12 000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C and resuspended in 50 mm N-[Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]glycine (TRICINE, pH 8.2) supplemented with DNAse I (1 μg ml−1) and 1 mm benzamidine. A crude cell extract (~600 mg protein) was prepared by breaking the suspended cells using a Constant Cell Disrupter (Constant Systems, Daventry, UK) three times at 25 MPa and 4 °C. Unbroken cells and debris were removed by centrifugation in a Beckmann JA20 at 12 000 × g for 25 min at 4 °C followed by removal of membrane fractions by centrifugation of the supernatant at 144 000 × g for 90 min (BECKMAN rotor SW28, Beckman, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The final supernatant (~300 mg protein) was concentrated using an Amicon stirred cell with PM10 ultrafiltration membrane (Millipore, Watford, UK). Aliquots of concentrated supernatant (~10 mg ml−1; 0.5 ml) were applied to an anion-exchange MonoQ 10 column (GE Lifesciences, Little Chalfont, UK) equilibrated with precooled (4 °C) 10 mm TRICINE (pH 8.2) supplied with 1 mm benzamidine. An increasing (0–1 M) NaCl gradient was used to elute fractions, which were assayed for MTO activity (see below). Fractions with MTO activity were concentrated using an Amicon stirred cell with a PM10 ultrafiltration membrane. Concentrated MonoQ 10 fractions containing mainly MTO were subjected to gel filtration using a Superdex 75 column (GE Lifesciences) equilibrated in precooled (4 °C) 10 mm TRICINE (pH 8.2) supplied with 1 mm benzamidine. Fractions containing active MTO showed a single dominant polypeptide on SDS-PAGE and were collected and concentrated as described above before storage at −80 °C. Further detail about protein purification is given in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. Analytical gel filtration was carried out using a Superdex 75 column equilibrated with 10 mm TRICINE, pH 8.2, 1 mm benzamidine, 0.15 M NaCl, at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1.

MTO activity assays

Routine analysis of enzyme activity was carried out by measuring MT degradation using gas chromatography (GC) for which MT was analyzed in headspace samples (100 μl) using an Agilent gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Cheshire, UK) fitted with a 30 m × 0.32 mm column (DB-1). Helium was used as the carrier gas at a temperature of 200 °C. The gas chromatograph had a flame ionization detector. Alternatively, MT was measured in headspace samples using a GC-2010plus (Shimadzu, Milton Keynes, UK) equipped with a Shim-1 column (30 m, 0.5 mm i.d.), at a temperature of 180 °C, with helium as carrier gas and a flame photometric detector. MTO activity was assayed in 10 mm TRICINE, pH 8.2 at 30 °C, typically using 0.1–0.5 mg of protein per assay. Alternatively, MTO activity was measured as substrate-induced O2 consumption in a Clark type oxygen electrode with and without addition of catalase (0.1 mg) and in the presence and absence of ZnSO4 (1 mm). The formation of formaldehyde by MTO was quantified using the Purpald reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) as described previously (Boden et al., 2011). Standard formaldehyde solutions were prepared from methanol-free formaldehyde in the range of 0–1 mm.

Protein electrophoresis

SDS-PAGE electrophoresis was carried out using standard protocols using precast gels supplied by Bio-Rad (Hemel Hempstead, UK) run in 1 × Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris) glycine buffer.

Metal analysis

Quantification of various elements contained in purified MTO was performed using inductively coupled plasma (ICP) mass spectrometry at the ICI Measurement Science Group, Wilton, Middlesbrough, UK.

Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy

The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectral properties of MTO were examined under various reducing (5 mm ascorbate, 1 mm dithionite) and oxidizing conditions (1.8 mm sodium hexachloroiridate (V)), and under enzyme assay condition in the presence of substrate (all at 25 °C). All analyses were carried out with a preparation of MTO of 9.2 mg ml−1 in 10 mm Tricine, pH 8.2 (with 1 mm benzamidine) on a Bruker EleXsyS 560 SuperX spectrometer fitted with a Bruker ER41116DM dual mode cavity (Bruker Biospin, Rheinstetten, Germany) and an Oxford ESR 900 Helium Flow Cryostat (Oxford Instruments plc, Abingdon, UK). EPR spectra of oxidized MTO were recorded at temperatures of 7 and 13 K after addition of sodium hexachloroiridate (V) (1.8 mm final concentration) using a microwave frequency of 9.66 GHz, microwave power of 0.63 mW, a modulation amplitude of 7 Gauss and a time constant of 81 ms. Further EPR spectra (four scans) were also recorded in the presence of enzyme substrates ethanethiol (1 mm) and oxygen (0.2 mm similar to assay conditions) using instrument settings as detailed above, except for a microwave power of 0.2 mW, a modulation amplitude of 7.6 Gauss at a temperature of 15 K.

X-ray spectroscopy analysis of methanethiol oxidase

X-ray absorption spectra were obtained in fluorescent mode on station B18 of the diamond light source (Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, Didcot, UK). This uses the technique of quick extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS), where the monochromator rotates at a constant rate during data acquisition. The fluorescence was detected using a nine-element germanium solid state detector. Data were obtained at the Cu K edge for a variety of samples and standards. All data were obtained with the samples at 77 K in a cryostat. To minimize radiation damage, the beam was rastered across the sample, which was moved between each scan. Each scan took about 20 min to acquire. Copper metal (foil), CuO and CuS were used as reference samples. The copper-containing enzyme tyrosinase (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as additional reference. Five samples of purified MTO were analyzed: as-isolated enzyme; enzyme treated with the oxidizing agent sodium hexachloroiridate (2 mm); enzyme treated with the substrate methanethiol; enzyme treated with the reducing agent sodium dithionite (1 mm). Detailed information about processing of data is provided in the Supplementary Information.

Identification of the gene encoding MTO in Hyphomicrobium sp. VS

N-terminal sequence data for MTO were obtained from gel slices of Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels by ALTA Bioscience, University of Birmingham, UK. Internal peptide sequences were determined by the biological mass spectrometry facility in the School of Life Sciences, University of Warwick, as described previously (Schäfer et al., 2005). We sequenced genomic DNA of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS using Illumina technology. After quality trimming, 26 777 191 reads with an average length of 60 bp were obtained. Reads were assembled using a combination of the CLCBio (Aarhus, Denmark) and Edena assemblers (Hernandez et al., 2014). No gap-closing was performed. This resulted in a draft genome consisting of 347 contigs (average length 9125 bp) with a total size of 3 722 323 bases (See Supplementary Table S3). Peptide sequences were matched against proteins predicted by the annotation pipeline. The draft genome assembly for Hyphomicrobium sp. VS is available on the MaGe Microscope platform at http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/agc/microscope/mage/index.php (Vallenet et al., 2013). The sequence of the contig containing mtoX, SCO1/senC and mauG has been deposited with the National Center for Biotechnology Information under accession number KY242492.

Phylogenetic analysis

Nucleic acid sequences were imported into Arb (Ludwig et al., 2004) and translated before aligning using clustalx as implemented in Arb. A phylogenetic tree was derived using amino acid sequence data based on the Arb neighbor joining method, using alignment columns corresponding to positions 85–300 of the MtoX polypeptide of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS and the PAM (point accepted mutation) distance correction as implemented in Arb. Bootstrapping (100 iterations) was carried out in MEGA 5 (Tamura et al., 2011).

Genetic analysis of mtoX in Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3

Locus SPOA0269 was identified by blast search as a homolog of mtoX in R. pomeroyi. Two PCR primer pairs were designed to amplify the flanking regions of SPOA0269 (5′-GCGAATTCTCGAAGCCATCGCTGG-3′ with 5′-CGGGATCCCATCGCCAGGGCACCGG-3′ and 5′-CGGGATCCTGGGCCTGGGCCGCGCGC-3′ with 5′-CCCAAGCTTCGGGGTCCGCCGGGTCAGG-3′). The resulting PCR products were digested with BamHI ligated together to form a clone with a truncated version of SPOA0269 (2/3 deletion in frame of the gene). The resulting fragment was digested with EcoRI and HindIII and then cloned into pK18sac. Then, a spectinomycin resistance (SpecR) cassette was cloned into a unique BamHI site within the truncated version of the gene. This construct was transferred by tri-parental conjugational mating with Escherichia coli containing the mobilizing plasmid pRK2013 as the helper strain (Figurski and Helinski, 1979) into rifampicin resistant R. pomeroyi J470 (Todd et al., 2011) (20 μg ml−1). Colonies were selected based on resistance to spectinomycin (200 μg ml−1) and sucrose (5%), but sensitivity to kanamycin (20 μg ml−1). Such colonies were checked by PCR and by southern blotting to show that they were mutated in SPOA0269.

Enzymatic assays of MTO activity in R. pomeroyi DSS-3

For the measurement of MT consumption by R. pomeroyi whole cells, R. pomeroyi DSS-3 wild-type and mtoX− strains were grown overnight at 28 °C in marine basal medium (MBM) (Baumann and Baumann, 1981) or MBM supplemented with 200 μg ml−1 spectinomycin, respectively, using succinate (10 mm) as a carbon source and NH4Cl (10 mm). Cultures were spun down and pellets were washed three times with fresh MBM. After that, cell suspensions were adjusted to an OD600=1.4 and inoculated (1/10 dilution) into 120 ml serum vials containing 20 ml MBM plus 0.5 mm MT. Vials were incubated at 28 °C and MT concentration in the headspace was measured at time 0 and after 6 h by GC as described in (Carrión et al. (2015)). Chemical degradation of MT in the medium control was subtracted from the MT removed in R. pomeroyi cultures to calculate rates of biological degradation of MT. Samples were pelleted, resuspended in Tris-HCl buffer 50 mm, pH 7.3 and sonicated (5 × 10 s) with an ultrasonic processor VC50 sonicator (Jencons, VWR, Lutterworth, UK). The protein content of the samples was estimated by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). Rates of biological MT disappearance are expressed as nmol min−1 per mg protein and represent the average of three biological replicates.

For MTO in vitro assays, R. pomeroyi DSS-3 wild-type and mtoX− were grown as above in the presence and absence of 0.5 mm MT for 6 h and pelleted. Cell pellets were washed three times with Tris-HCl buffer 50 mm, pH 7.3. Pellets were resuspended in 20 ml of Tris-HCl buffer and sonicated (as above). Cell lysates of 5 ml were placed in 20 ml serum vials to which 0.25 mm MT was added. MT concentration in the headspace was measured at time 0 and after 2 h of incubation at 28 °C by (GC) as described previously (Carrión et al., 2015). Cell protein content and rates of biological degradation of MT were determined as described above.

There was no difference in the growth of the mtoX mutant strain compared to R. pomeroyi DSS-3 wild type in the presence of MT (0.5 mm).

Transcriptional analysis of mtoX in Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3 and Rhizobium leguminosarum

The region of the R. pomeroyi DSS-3 genome that likely spanned the promoter of the SPOA0268-0272 operon was amplified from genomic DNA using primers GCGAATTCATCGAACCGCAATAGACCAC and GCCTGCAGGATCTTGGGCATATAGGGCG and cloned into the lacZ-reporter plasmid pBIO1878 (Todd et al., 2012) to form an mtoX-lacZ fusion plasmids. The mtoX-lacZ fusion plasmid was digested with NsiI and PstI and religated to delete a ~800 bp 3′ fragment and form a SPOA0268-lacZ fusion plasmid. These plasmids were transferred by tri-parental conjugational mating (as above) into R. pomeroyi J470 and transconjugants were selected on rifampicin (20 μg ml−1) plus spectinomycin (200 μg ml−1). Transconjugants were grown overnight in MBM with succinate (10 mm) as carbon source (González et al., 1997). The media either contained or lacked 5 mm DMSP, 1 mm MMPA, 0.1 mm MT or 0.1 mm DMS. The cells were assayed for β-galactosidase activity essentially as described previously (Rossen et al., 1985).

Identification of MTO homologs in bacterial genomes

MTO homologs were identified in microbial genomes based on BLASTP searches against assembled genomes at Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) (Markowitz et al., 2009). MtoX amino acid sequences of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS, R. pomeroyi DSS-3 (locus SPOA0269) and Methylophaga thiooxydans (MDMS009_768) were used as queries. All hits used in further analysis had an e-value of 1e−151 or lower and a minimum pairwise identity at the level of the entire polypeptide of 52% or higher. On the basis of preliminary analyses showing support for a signal peptide in MTO, the start codons of two orthologous genes that appeared truncated were corrected to start at alternative start codons further upstream (locus GPB2148_3671 in marine gammaproteobacterium HTCC2148 was extended by 26 amino acids, while MDMS009_211 in M. thiooxydans was extended by 46 amino acids) as they appeared to have incomplete N-termini. Orthologs from Phaeobacter sp. LSS9 (714 amino acids) and Comamonadaceae bacterium EBPR_Bin_89 (335 amino acids) were excluded as the length of the polypeptides significantly deviated from the remaining range observed (410–491 amino acids). Sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW (Larkin et al., 2007).

Detection of mtoX homologs in metagenomic data sets

Metagenomic data sets were obtained from the CAMERA (Sun et al., 2011) project website and searched for mtoX homologs using tblastn and the amino acid sequences of MtoX of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS, M. thiooxydans (locus tags MDMS009_211 and MDMS009_768) and R. pomeroyi DSS-3 (SPOA0269) as queries with a cutoff in e-value of 1e−20. In case of libraries that represented short read data (that is, <125 bp), a cutoff value of 1e−05 was used. Similarly, the metagenomic data sets were searched for homologs of the DMSP demethylase dmdA (R. pomeroyi locus SPO1913) and the bacterial housekeeping gene recA from E. coli at a cutoff of 1e−20 to estimate the fractional abundance of mtoX-containing cells in the bacterial community and compare it to that of the DMSP demethylase gene dmdA.

Testing of MT oxidation in bacterial isolates

The potential to degrade MT by a range of pure cultures was assessed by monitoring changes in the MT concentration in the headspace after addition of 100 μM MT (Supplementary Table S4). Mineral salts medium was used to monitor MT oxidation without any other carbon source added. For Methylococcus capsulatus bath and Methylocystis sp., ATCC 49242 were tested for MT oxidation in NMS medium (Whittenbury et al., 1970) that contained methane in addition to MT (20% v/v and 40% v/v methane added to the headspace for M. capsulatus and Methylocystis, respectively). Pseudovibrio gallaeciensis and P. ascidiaceicola were grown in marine broth (Difco) to which MT was added. Sterile controls were incubated for each medium used to account for chemical MT degradation.

PCR amplification and cloning of MTO from enrichment cultures and environmental samples

PCR primers were designed based on an alignment of bacterial mtoX homologs (Supplementary Table S5). Primers were custom synthesized by Invitrogen Life Technologies (Paisley, UK) and initially tested using Hyphomicrobium sp. VS and M. thiooxydans DNA as template showing that a combination of primers 44F1/2 and 370R1/2/3 successfully amplified mtoX fragments from these two reference isolates. Further optimization of PCR conditions was carried out with DNA from additional bacterial isolates containing mtoX homologs and those showing potential for MT degradation (Supplementary Table S4). Unless noted otherwise, the PCR conditions used were 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 60 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1.5 min, followed by 72 °C for 5 min.

The presence and diversity of mtoX genes in enrichments and environmental samples was assessed using the newly designed primers on DNA extracted from Brassica rhizosphere soils enriched with dimethylsulfide or methanol (Eyice and Schäfer, 2016), DNA samples of 13C2-DMS stable isotope probing experiment carried out with soil samples (Eyice et al., 2015), Brassica oleracea rhizosphere soil, and surface sediment from the river Dene (Wellesbourne, Warwickshire, UK). DNA was extracted from 2 ml of enrichment samples or 0.5 g of soil/sediment samples using the FastDNA Spin kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In addition, mtoX diversity was assessed in surface sediments of a coastal saltmarsh (Stiffkey, Norfolk, UK). Five replicate sediment samples were obtained from the surface 5 mm oxic sediment layer of a small saline pool along transects starting at a patch of Spartina anglica plants at the periphery of the pool, extending 50 cm toward its center. The pH of the pool was 8.0, the water temperature was 16 °C. Samples were transported back to the laboratory on ice, before being centrifuged at 14 000 r.p.m. to remove the water and retain the sediment pellet. Samples were stored at −20 °C prior to DNA extraction. Extraction of DNA from the sediment samples was performed using a Qbiogene FastDNA SPIN Kit for soil (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Eluted DNA was stored at −20 °C. PCR on Stiffkey sediment samples was carried out using primers MtoX41Fmodv2_inos and MTOX346Rmod (compare Supplementary Table S5) using a cycling regime consisting of a 95 °C hot start followed by 40 cycles of denaturation for 45 s, annealing for 45 s and elongation for 60 s at 95, 52 and 72 °C, respectively. A final extension step of 72 °C for 6 min followed. All PCR products were cloned in pCRTOPO 2.1 (Invitrogen Life Technologies). DNA sequencing of randomly chosen clones was carried out at the University of Warwick Genomics Centre using BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit and ABI Prism 7900HT or ABI3100 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Sequences of mtoX genes obtained from environmental samples have been deposited at the NCBI under accession numbers KY056824-KY057025.

Results

Purification and characterization of methanethiol oxidase from Hyphomicrobium sp. VS

We purified the native MTO enzyme from soluble extracts of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS grown on DMS or a combination of methanol and DMS using anion-exchange (MonoQ) chromatography followed by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 75 column and another MonoQ column. Fractions exhibiting MTO activity and those adjacent on the final column run were analyzed on SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Figure S1A). From this it could be concluded that fraction 18 that exhibited MTO activity was dominated by a single polypeptide with an estimated molecular weight of 46 kDa. All other analyses were performed with this fraction. Electrospray-ionisation mass spectroscopy of this fraction revealed a polypeptide with a molecular mass of 46 186 Da (Supplementary Figure S2). Analysis of MTO by native gel electrophoresis suggested a molecular weight of ~180–200 kDa (Supplementary Figure S1B). Reanalysis of the excised band by SDS-PAGE resulted in a single band of 46 kDa (result not shown). Analytical gel filtration suggested an apparent size of 200 kDa (Supplementary Figure S1C) also indicating that MTO of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS is a homotetrameric enzyme.

The purified enzyme degraded MT and ethanethiol, but not methanol, methylamine or dimethylsulfide. When MT was the substrate, we found evidence for the production of formaldehyde, hydrogen sulfide and hydrogen peroxide, although we did not quantify the latter. The O2 dependency of MT conversion was shown by measuring activity with an oxygen sensor (Clark type). The ratio O2/MT consumed was around 0.75±0.05 (with 1.2 to 26 μm MT converted). This is lower than the 1.0 expected from the proposed stoichiometry (CH3SH+O2+H2O → HCOH+H2S+H2O2) and most likely caused by a very small contamination with highly active catalase reforming additional oxygen from hydrogen peroxide. This has been observed before (Suylen et al., 1987). The remaining slow oxygen consumption after MT was depleted (rate dropping from 1.8 μm O2 per min to 0.2 μm O2 per min after 5 μm MT was depleted) was attributed to sulfide oxidation. Apart from being a (competitive) substrate for MTO, the sulfide produced in the MT oxidation was shown to be an inhibitor. This effect was also demonstrated before for the MTO purified from Hyphomicrobium strain EG (Suylen et al., 1987). Adding Zn ions to the assay buffer to trap the produced sulfide resulted in 20% faster initial MT conversion rates (when tested at 5 μm MT, oxygen respiration increased from 5.5 to 6.7 μm O2 per min) and completely abolished the sulfide oxidation. Upon acidification of the final reaction mixture, at least 75% of the added MT sulfur was recovered as hydrogen sulfide. After including Zn2+ in the assay mixture, O2 consumption rates were constant (zero order kinetics) over almost the whole MT concentration range tested (1–20 μm MT). From this, it can be concluded that the Km value is below 1 μm MT, which is below the detection limit of the respiration measurements. Using gas chromatographic analysis of MT (detection limit 0.05 μm MT), MT consumption rates at much lower concentrations could be tested. This resulted in a very low affinity constant (Km) for MT of 0.2–0.3 μm. The Km for MT of the MTO was at least 10 × lower than previously reported values for Hyphomicrobium sp. VS (5–10 μm) and T. thioparus (31 μm) (Gould and Kanagawa, 1992; Pol et al., 1994). This may be explained by the trapping of sulfide in our assays. The Vmax was about 16 μmol mg−1 protein per min (Supplementary Figure S3). Formaldehyde was formed stoichiometrically, we observed formation of 4.1 nmol (±0.5) from 4 nmol of MT and 36.4 nmol (±2.6) from 40 nmol MT.

MTO of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS is a metalloenzyme and Cu is involved in the redox process of MT oxidation

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry showed that the purified enzyme preparation contained 3.5 mol Ca and 1.4 mol of Cu per mol of MTO tetramer (Supplementary Table S6). To further assess the potential role of Cu and Ca for MTO activity, we carried out chelation experiments using ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) and ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA). Incubation of the enzyme with EDTA but not EGTA reduced the activity of MTO by 44% suggesting that Cu but not calcium has a role in the catalytic activity of MTO (Table 1).

Table 1. Effect of chelators on the activity of Hyphomicrobium VS methanethiol oxidase.

| Sample | Specific activity (μmol MT min−1 mg−1 protein) |

|---|---|

| MTO—no chelator | 12.9±1.5 |

| MTO—EDTA-treated | 5.7±1.1 |

| MTO—EGTA-treated | 12.5±0.9 |

Abbreviations: EGTA, ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid; MT, methanethiol; MTO, MT oxidase.

A role of Cu in enzyme function was also supported by EPR spectroscopy and EXAFS for which a detailed description of the results is provided in the Supplementary Data. In brief, the EPR signals of resting and oxidized MTO samples did not have well-resolved signals that would be expected from Cu(II) mono-nuclear Cu site(s) (Supplementary Figure S4). Instead, there were signals that were probably due to two magnetically interacting Cu(II) centers, similar to CuA in cytochrome c oxidase or nitrous-oxide reductase, which are both binuclear copper centers, as well as Cu model complex possibly also without bridging sulfur (Antholine et al., 1992; Solomon et al., 1996; Monzani et al., 1998; Kaim et al., 2013). The changes in features in the EPR spectra with addition of substrate also indicated changes in the coordination of Cu when substrate binds (Supplementary Figure S5), which could indicate direct interaction of the substrate with the Cu center. Although at this point the exact nature of the Cu environment and status cannot be fully resolved, the data suggest that it is likely a binuclear site, as the data do not support a single atom Cu(II) center. Analysis of MTO by means of extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) were consistent with the EPR data in that the oxidation state of the copper was between 1 and 2. The data indicated that the copper in the resting enzyme (in the absence of substrate) was coordinated by four nitrogen atoms with a Cu–N bond distance of 1.99 Å. EXAFS data from samples treated with substrate (methanethiol) or the reducing agent sodium dithionite showed that the copper was somewhat more reduced than the as-isolated, which was in line with an increased Cu–N bond length shown by the EXAFS data. The substrate-treated sample had fewer Cu–N ligands (2–3) than in the as-isolated enzyme. These observations are consistent with changes in oxidation state and coordination of the copper centers upon interaction with the substrate (Supplementary Figures S6 and S7) and support a role of Cu in the function of the enzyme.

The identification of the gene encoding MTO reveals that MTO is a homolog of the selenium-binding protein family (pfam SBP56), has a conserved genomic context and that MTO is a periplasmic enzyme

The gene encoding MTO was identified based on N-terminal and de novo peptide sequencing against a draft genome sequence of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS. N-terminal sequencing of the purified MTO resulted in the identification of 15 amino acids, DETXNSPFTTALITG, with position X potentially a cysteine residue, indicating a processed N-terminus. In addition to the N-terminal sequence, internal peptide sequences were obtained (Supplementary Figure S8). Using peptide data in BLAST searches against the draft genome of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS available on microscope (Vallenet et al., 2013), we identified the gene encoding MTO designated hereafter as mtoX (locus tag HypVSv1_1800007). A contig of 18.4 kb was assembled and confirmed by PCR and sequencing that contained a genomic region including the mtoX and additional genes downstream that are likely to be involved in its maturation (Genbank accession number KY242492). The mtoX gene is 1308 bp in size, encoding a polypeptide of 435 amino acids. Signal-P analysis (Bendtsen et al., 2004) indicated that MTO contained a signal peptide with a predicted cleavage site at position 24 resulting in an N-terminus identical to the one determined experimentally of the purified MTO polypeptide. No transmembrane helices were identified by the software TMHMM (Krogh et al., 2001) in the sequence representing the processed polypeptide, suggesting MTO to be a soluble periplasmic enzyme. The calculated molecular weight of the processed periplasmic MTO was 45 905 Da (46 192 Da assuming 4 Ca and 2 Cu in addition), in good agreement with the observed molecular weight on SDS-PAGE and the molecular weight estimated by Electrospray-ionisation mass spectroscopy (46 186). A conserved domain search with the predicted MTO amino acid sequence confirmed its homology to members of pfam05694, the SBP56 superfamily. A BLASTP search with the MTO protein sequence revealed hits with high homology in all three domains of life; including against bacteria (50–79% identity), archaea (26–29% identity) and eukarya (human SELENBP1 26% identity). The highest identities (77–79%) were with proteins annotated as selenium-binding proteins from other Hyphomicrobium species. Despite this similarity to known Se-binding proteins, no Se was found as judged by ICP elemental analysis. However, there are many cases of metalloproteins in which members of the same polypeptide family contain different specific metal co-factors, for example, in proteins of the FUR regulator superfamily (Fillat, 2014).

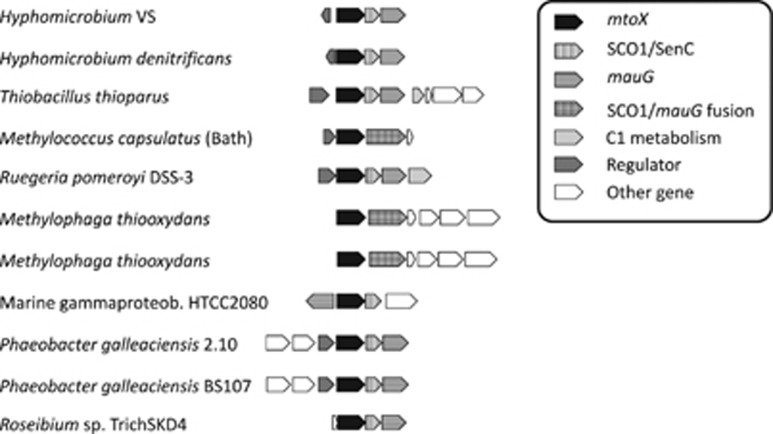

Genes downstream of mtoX in Hyphomicrobium sp. VS are predicted to encode homologs of the copper chaperone SCO1/SenC (Interpro: IPR003782) and of MauG, a protein with sequence similarity to diheme cytochrome c peroxidases that are required for the synthesis of tryptophan tryptophylquinone (TTQ) prosthetic groups (Wang et al., 2003). The MTO, SCO1/SenC and MauG-encoding genes formed an operon-like structure (Figure 2). Based on the Cu content of MTO, the SCO1/SenC domain protein may be involved in MTO maturation. In Paracoccus denitrificans, the mauG gene encodes an enzyme responsible for post-translational modification of the methylamine dehydrogenase pre-protein to produce a protein-derived TTQ co-factor (Wang et al., 2003).

Figure 2.

Genomic context of mtoX genes in selected bacteria showing the clustering of mtoX with genes encoding proteins containing SCO1/SenC and/or MauG domains, see inset for definition of coloring and patterns to particular gene annotation. As discussed in the text, in some instances, genes are encoding fusion proteins of SCO1 and mauG domains. Further information about the presence of SCO1 and MauG domain encoding genes in the vicinity of mtoX genes is given in Supplementary Table S7.

Phylogeny and distribution of mtoX in bacterial genomes

Homologs of mtoX were identified by BLASTX searches and a phylogenetic analysis was carried out based on the alignment of predicted amino acid sequences. This showed that MTO from Hyphomicrobium sp. VS belongs to a clade annotated as selenium-binding proteins (Supplementary Figure S9). In addition, the cluster with Hyphomicrobium sp. VS-MTO-like SBP included many organisms known to degrade one-carbon compounds (including DMS and MT), DMSP (for example, the model bacterium R. pomeroyi DSS-3) or sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. In many of these organisms, mtoX was also co-located with the SCO1/senC and mauG genes, or with genes encoding these two protein domains fused in a single gene as, for instance, in M. thiooxydans (Figure 2, Supplementary Table S7). In this marine gammaproteobacterium that degrades DMS via MT (Boden et al., 2010), expression of polypeptides identified as selenium-binding protein was demonstrated during growth on DMS by peptide sequencing (Schäfer, 2007).

The capacity to degrade MT was tested in selected isolates. All tested bacterial strains containing the mtoX gene could degrade MT supporting a role for MTO in MT oxidation in these bacteria including R. pomeroyi DSS-3 (see below), Hyphomicrobium denitrificans (DSM1869), M. capsulatus (Bath), Methylocystis sp. ATCC 49242, M. thiooxydans DMS010, T. thioparus TK-m, T. thioparus E6, Phaeobacter galleciensis (DSM 17395) and Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola (DSM 16392). Complete degradation of MT was observed within 2 days and was compared to sterile controls in which MT was not degraded over the same time period. In comparison, several strains that lacked the mtoX gene could not degrade MT, for example, Methylophaga marina and Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 (Supplementary Table S4).

Genetic analysis of mtoX in Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3

R. pomeroyi DSS-3 produces MT as an intermediate, while catabolizing DMSP via the demethylation pathway (Reisch et al., 2011b). The R. pomeroyi mtoX gene (SPOA0269), located on a megaplasmid, encodes a protein with 57% and 71% identity and similarity, respectively, to the MTO of Hyphomicrobium VS. To study the role of mtoX in MT degradation, SPOA0269 was replaced with a spectinomycin cassette in the R. pomeroyi genome.

MT removal assays conducted at the whole-cell level (0.5 mm MT) showed that wild-type R. pomeroyi had a rate of MT removal (23±1 nmol MT min−1 per mg protein) ~14-fold higher than those observed for mtoX− mutant cultures (1.7±1.4 nmol MT min−1 per mg protein) supporting a role for MTO in MT oxidation (Table 2). The enzyme responsible for the low level MT removal activity remaining in the mtoX− mutant was not identified.

Table 2. MT consumption by whole cells and lysates of R. pomeroyi DSS-3 wild-type and mtoX− strains (n=3).

| Sample | MT consumption (nmol MT min−1 per mg protein) |

|---|---|

| Whole-cell assays with 0.5 mm MT | |

| Wild type | 23.4±1.2 |

| mtoX− | 1.7±1.4 |

| Cell lysate assays with 0.25 mm MT from cells pre-incubated in the presence (0.5 mm, +MT) or absence of MT (−MT) | |

| Wild-type −MT | 39.2±14.4 |

| Wild-type +MT | 139.2±25.5 |

| mtoX− −MT | No MT degradation |

| mtoX− +MT | No MT degradation |

Abbreviation: MT, methanethiol.

MT consumption is expressed as nmol MT removed min−1 per mg protein.

Assays of MTO activity in cell lysates of wild-type and mtoX− mutants with or without prior incubation with MT (0.5 mm) further support the role of the mtoX gene in MT oxidation and showed its activity to be inducible. Cell lysates of wild-type R. pomeroyi that had not been pre-incubated with MT consumed MT (0.25 mm) at a rate of 39±11 nmol MT min−1 per mg protein. In wild-type cultures pre-incubated with MT, the degradation rate increased fourfold to 139±26 nmol MT min−1 per mg protein. Cell lysates of mtoX− mutants did not remove MT under the same conditions, irrespective of being pre-incubated in presence or absence of MT (Table 2). Thus, the R. pomeroyi gene SPOA0269 likely encodes a functional MTO enzyme whose level of MT oxidation was upregulated by exposure to MT.

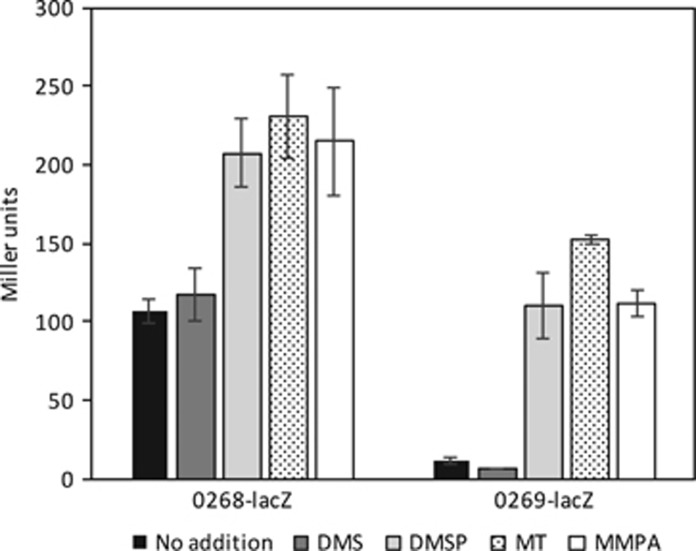

The transcription of Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3 mtoX is enhanced by MT

R. pomeroyi DSS-3 had a similar conserved mtoX gene neighborhood in which there is likely co-transcription with a gene encoding a SCO1/SenC domain protein (SPOA0270) and a mauG-like gene (SPOA0271) (Figure 2). Directly upstream of mtoX in R. pomeroyi is an IclR family transcriptional regulator (SPOA0268), and this gene arrangement is conserved in marine Roseobacter clade bacteria (Supplementary Table S7). We noted in microarrays carried out in (Todd et al., 2012) that the transcription of the predicted operon (SPOA0268-0272) containing mtoX was significantly enhanced (two to fivefold) by growth of R. pomeroyi in the presence of DMSP. To confirm these observations, transcriptional lac fusions were made to the SPOA0268 and mtoX genes and assayed in R. pomeroyi in the presence of potential inducer molecules. Consistent with the microarray results, transcription of both SPOA0268 and mtoX was enhanced by DMSP, MMPA and most significantly by MT (~14-fold for mtoX), but not DMS (Figure 3). These results are consistent with the cell lysate assays and MT being the inducer molecule since both DMSP and MMPA are catabolized to MT by DMSP demethylation.

Figure 3.

Transcriptional regulation of Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3 SPOA0268 and the methanethiol oxidase gene encoded by SPOA0269, assessed by beta galactosidase transcriptional fusion assay using various potential inducers. Values are reported in Miller units.

Diversity of mtoX in environmental samples

The diversity of mtoX in environmental samples was assessed by PCR using newly designed primers 44F1/2 and 370R1/2/3 (Supplementary Table S5), which had been optimized by testing against a range of bacterial isolates. PCR with these primers resulted in amplicons of the expected size (~987 bp) (Supplementary Figure S10). Performing the PCR with DNA extracted from samples that were shown or would be expected to contain bacteria capable of methanethiol degradation (based on their known degradation of DMS and DMSP for instance) also yielded bands of the correct size. These samples included DNA extracted from DMS enrichment cultures from Brassica rhizosphere soil, bulk agricultural soil (Eyice and Schäfer, 2016), rhizosphere sediment of S. anglica (a DMSP-producing plant) obtained from Stiffkey saltmarsh (Norfolk, UK) and surface sediments of Stiffkey saltmarsh. Saltmarshes are known to be environments with high turnover of DMSP, DMS and MT (for example, Kiene, 1988a; Kiene and Capone, 1988b). Stiffkey saltmarsh samples used here had high DMS oxidation rates and enrichment of organisms containing mtoX genes was readily observed (Kröber and Schäfer; Pratscher et al., unpublished data).

Annealing temperatures used in these PCRs varied between 53 and 60 °C. The mtoX amplicons obtained with the B. oleracea rhizosphere DMS enrichment were cloned and clones chosen at random were sequenced. The mtoX gene sequences obtained belonged to two clades closely related to T. thioparus (Figure 4). Amplification efficiency of mtoX from DNA extracted from Stiffkey saltmarsh sediment samples was more variable and the primers were refined further (MtoX41Fmodv2_inos and MTOX346Rmod, Supplementary Table S5) to introduce degeneracies that improved their performance with these samples (result not shown). Surface sediment mtoX gene diversity was investigated in a tidal pool in Stiffkey saltmarsh using five independent samples from two transects across the pool. The analysis of randomly chosen clones from mtoX gene libraries prepared for these five surface sediment samples showed a high diversity of mtoX genes in the saltmarsh environment (Figure 4), while there appeared to be little variation in mtoX diversity between samples from the saltmarsh according to terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (result not shown). This showed Stiffkey saltmarsh mtoX sequences to belong to several distinct clades that lacked cultivated representatives. The mtoX sequences from Stiffkey saltmarsh clustered more closely with mtoX of gammaproteobacteria rather than those of alpha- or betaproteobacteria. The most closely related mtoX from cultivated strains were those of marine gammaproteobacterium HTCC2148, Sedimenticola selenatireducens and Dechloromarinus chlorophilus. MTO-encoding genes detected in DNA extracted from the DMS enrichments with Brassica rhizosphere soil and 13C-DNA of DMS-SIP experiments of soil and lake sediment samples (Eyice et al., 2015) were related to betaproteobacterial taxa such as T. thioparus and Methyloversatilis sp. (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of translated methanethiol oxidase genes obtained from public databases, selected bacterial isolates by PCR, clone libraries of enrichment cultures and DNA extracted from surface sediments of Stiffkey saltmarsh. The tree was based on an alignment of full length and partial MtoX sequences in Arb and was derived using the neighbor joining algorithm and PAM correction implemented in Arb from a region comprising amino acid positions 85–300 of the Hyphomicrobium VS MtoX polypeptide. Bootstrap values (100 iterations) were derived in Mega 5, only those supporting terminal nodes with a confidence of 75% or higher are shown. Taxa shown in bold tested positive for MT oxidation.

Detection of mtoX in metagenomic data sets

Homologs of mtoX of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS, M. thiooxydans and R. pomeroyi were also detected in metagenomic data sets (Table 3). The relative abundance of mtoX-containing bacteria was estimated based on the frequency of detection of mtoX in comparison to recA, a universal housekeeping gene present in all bacteria and compared to that of dmdA, the DMSP demethylase. The relative abundance of mtoX varied across the different data sets (0–46%) and, in most cases, was lower than that of dmdA. On the basis of this analysis, it is difficult to delineate a general abundance pattern of mtoX-containing bacteria in different environments, however, it demonstrates that mtoX can be an abundant gene in some microbial communities. Selected mtoX sequences of sufficient length from the global ocean survey (Rusch et al., 2007) and other metagenomic data sets were included in the phylogenetic analysis (Figure 4). Global ocean survey mtoX formed distinct clades, some of which were closely related to saltmarsh sediment mtoX types, or to the marine gammaproteobacterium HTCC2080, suggesting that most of the mtoX detected in metagenomics studies are originating from previously uncultured bacteria.

Table 3. Analysis of metagenomic data sets for the presence of mtoX, dmdA and recA homologs.

| Metagenome name (CAMERA project name) | Biome | No. of sequences |

Number of hits |

Estimate |

See footnote | CAMERA/imicrobe/NCBI data set accession | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mtoX | dmdA | recA | % Of cells with mtoX | % Of cells with dmdA | |||||

| Antarctica aquatic microbial metagenome | Antarctic lake | 64 626 265 | 230 | 533 | 504 | 45.6 | 106 | PRJNA33179 | |

| Botany bay metagenomes | Coastal marine pelagic | 15 538 531 | 95 | 551 | 511 | 18.6 | 108 | CAM_PROJ_BotanyBay | |

| Western channel observatory microbial metagenomic study | Coastal marine pelagic | 7 354 754 | 46 | 622 | 623 | 7.4 | 100 | CAM_PROJ_WesternChannelOMM | |

| Metagenomic analysis of the North Atlantic spring bloom | Marine pelagic | 6 784 781 | 8 | 268 | 510 | 1.6 | 53 | CAM_PROJ_BATS | |

| Microbial community genomics at the HOT/ALOHA | Marine pelagic | 5 687 251 | 10 | 524 | 534 | 1.9 | 98 | CAM_PROJ_HOT | |

| North Pacific metagenomes from Monterey Bay to Open ocean (CalCOFI line 67) | Marine pelagic | 5 618 147 | 7 | 4 | 117 | 6.0 | 3 | CAM_P_0000828 | |

| Monterey bay transect CN207 sampling sites | Coastal marine pelagic | 5 248 980 | 19 | 230 | 514 | 3.7 | 45 | CAM_P_0000719 | |

| Guaymas Basin deep-sea metagenome | Marine deep water | 4 970 673 | 56 | 69 | 340 | 16.5 | 20 | CAM_P_0000545 | |

| Marine metagenome from coastal waters project at Plymouth marine laboratory | Coastal marine pelagic | 1 444 540 | 3 | 79 | 172 | 1.7 | 46 | CAM_PROJ_PML | |

| Marine bacterioplankton metagenomes | Marine pelagic | 1 314 590 | 1 | 80 | 239 | 0.4 | 33 | CAM_PROJ_Bacterioplankton | |

| Sargasso sea bacterioplankton community | Marine pelagic | 606 285 | 11 | 21 | 91 | 12.1 | 23 | a | CAM_PROJ_SargassoSea |

| Sapelo island bacterioplankton metagenome | Coastal marine pelagic | 354 908 | 9 | 14 | 30 | 30.0 | 47 | b | CAM_PROJ_SapeloIsland |

| Washington lake metagenomes | Lacustrine | 252 427 | 4 | 12 | 75 | 5.3 | 16 | PRJNA30541 | |

| Two HOT fosmid end depth profiles (HOT179 and HOT186) | Marine pelagic | 194 593 | 2 | 20 | 54 | 3.7 | 37 | CAM_P_0000828 | |

| Waseca county farm soil Metagenome | Soil | 139 340 | 1 | 4 | 16 | 6.3 | 25 | c | CAM_PROJ_FarmSoil |

| Hydrothermal vent Metagenome | Marine hydrothermal vent | 49 636 | 1 | 0 | 28 | 3.6 | 0 | CAM_PROJ_HydrothermalVent | |

Abbreviation: DMSP, dimethylsulfoniopropionate.

The distribution of hits against sampling sites (‘control’ or ‘DMSP’) in the Sargasso sea bacterioplankton study was as follows: mtoX 7 control, 4 DMSP; dmdA 4 control, 17 DMSP; recA 42 in control, 49 in DMSP.

Because of the very short reads in Sapelo Island bacterioplankton metagenome an e-value cutoff of 1e−05 was used. Hits at that level had a high pairwise similarity, for dmdA, there were shorter 100% identity hits with higher e-values than the cutoff used, which were therefore rejected by this approach suggesting this as a stringent cutoff value.

The dmdA hits in the Waseca county farm soil study had low maximum pairwise identities between 24 and 29% at the amino acid level.

Discussion

New insights into biochemical, genetic and environmental aspects of bacterial methanethiol oxidation presented here address a major knowledge gap in the biogeochemical sulfur cycle and the fundamental understanding of MT degradation by bacteria. Data presented here indicate that MTO is a periplasmic enzyme that is present in a wide range of bacteria, not limited to those known to produce MT as a metabolic intermediate during DMS and DMSP degradation, such as Hyphomicrobium VS, Thiobacillus sp. and R. pomeroyi DSS-3. The mtoX gene was also found in diverse cultivated bacteria that had not previously been recognized for their potential to degrade methanethiol. Homologous genes are also present in archaea and eukarya (including humans). In addition, the overall diversity of mtoX in environmental samples suggests that the potential for MT oxidation is also present in diverse uncultivated microorganisms and that MTO is a widely distributed enzyme in different terrestrial and marine environments, many of which have demonstrated potential for degradation of methylated sulfur compounds. MTO requires copper for its catalytic activity, and in R. pomeroyi, the gene encoding MTO is induced by MT. The enzyme from Hyphomicrobium sp. VS has a very high affinity for MT, with a Km (0.2–0.3 μm) at least 10-fold lower than those previously reported, which may explain the low MT concentrations found in the environment.

Distinct molecular weights for MTOs from Hyphomicrobium, Thiobacillus and Rhodococcus strains have been reported previously. On the basis of high sequence homology of mtoX genes found in several Hyphomicrobium and Thiobacillus strains and the fact that previously purified MTOs from Hyphomicrobium sp. EG (Suylen et al., 1987) and T. thioparus (Gould and Kanagawa, 1992) had similar molecular weights to the MTO of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS suggests that the previously purified MTOs are similar enzymes. Although previous studies reported MTO as a monomeric enzyme in Hyphomicrobium sp. EG and T. thioparus Tk-m (Suylen et al., 1987; Gould and Kanagawa, 1992), rather than a homotetramer as in this study, these differences may be due to sensitivity of the MTO’s oligomeric state to pH. At pH 8.2, we found tetrameric MTO, but when we carried out analytical gel filtration at pH 7.2, as used by Suylen et al. (1987), MTO was detected in monomeric and tetrameric state (result not shown). Other observed differences between these MTOs may be due to different analytical approaches that were employed. For instance, a role of metals in MTO activity was previously ruled out based on chelation experiments, but these can fail to deplete the metals from the enzyme depending on variations in incubation conditions. The presence in and role of Cu for the functioning of the enzyme from Hyphomicrobium sp. VS is supported by ICP mass spectrometry analysis, changes in EPR spectra recorded with MTO in resting, reduced and oxidized state, and by chelation experiments showing a reduced activity of the enzyme. The presence of genes encoding putative Cu chaperones (SCO1/SenC) in close proximity to mtoX homologs in many bacterial genomes provides further circumstantial evidence for a role of copper in MT oxidation and provides a focus for future genetic and biochemical studies.

Besides the presence of a mauG homolog, involved in maturation of a protein-derived TTQ co-factor in methylamine dehydrogenase, we found supporting evidence that the MTO also contains a TTQ co-factor. The PDB database contains the structure of the heterologously expressed SBP56 protein of Sulfolobus tokodaii (PDB entry: 2ECE). Analysis of the structure of this non-matured protein (no copper, no TTQ) made it possible to identify the putative ligands involved in copper binding (histidines) and TTQ synthesis (tryptophans) in the Sulfolobus homolog (Supplementary Figure S11). Alignments of the tryptophan and histidine residues identified showed strict conservation over the three domains of life. EPR and EXAFS analyses suggest that Cu in MTO of Hyphomicrobium sp. VS is coordinated by four nitrogen atoms, which would fit with the strictly conserved histidine residues which in Hyphomicrobium sp. VS-MTO are His89, His90, His140, His412 (Supplementary Figures S8 and S12). The structural information and the presence of the SCO1/senC and mauG-like genes support the presence of a TTQ co-factor and two copper atoms per monomer; further, if we assume 4 Ca and 2 Cu per monomer, the calculated mass exactly fits the Electrospray-ionisation mass spectroscopy analysis: 46 193 vs 46 186 Da. The arrangement of the genes mtoX, SCO1/senC and mauG encoding MTO, a copper chaperone, and homolog of the enzyme known to be involved in maturation of a protein-derived TTQ co-factor in methylamine dehydrogenase was highly conserved in a wide range of bacteria (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S7).

The role of MTO in metabolism of MT and DMSP as well as its transcriptional regulation were demonstrated in R. pomeroyi showing that this enzyme has an important role in metabolism of DMSP. Transcriptional fusions of the IclR type regulator upstream also demonstrated that MT as well as DMSP and MMPA (which are degraded to MT) induced MTO transcription. Interestingly, despite the presence of a functional MTO, it has long been known that R. pomeroyi DSS-3 liberates MT when grown in the presence of DMSP, this being one of the products of the DMSP demethylation pathway (Reisch et al., 2011b). Thus, under these circumstances, the MTO does not have sufficient activity to oxidize all the DMSP-dependent MT that is formed. However, we noted (unpublished) that the mtoX− mutant R. pomeroyi DSS-3 released more MT (~1.5-fold) when grown in the presence of DMSP than did the wild type.

The identification of the gene encoding MTO in bacteria has allowed assessing the distribution of the enzyme in the environment and identified its evolutionary relationship to the selenium-binding protein family (SBP56), a protein family that has as yet an unresolved function. Metal analysis by ICP mass spectrometry did not show the presence of selenium in MTO. SBP56 is a highly conserved intracellular protein (Bansal et al., 1989). Previous reports stated that it is involved in the transport of selenium compounds, regulation of oxidation/reduction and late stages of intra-Golgi protein transport, but its exact role has remained unclear (Jamba et al., 1997; Porat et al., 2000; Ishida et al., 2002). Homologs of SBP56 were found in human, mouse, fish, horse, birds, abalone and plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana and maize in addition to bacteria and archaea (Jamba et al., 1997; Flemetakis et al., 2002; Self et al., 2004; Song et al., 2006). The human SBP56 homolog has been shown to be a methanethiol oxidase ((Pol et al.), Nat Genet, in revision). To what extent the other SBP56 have similar function to MTO needs to be addressed, but a possible relationship of SBP56 with C1 metabolism was previously pointed out based on the presence of the SBP56-encoding gene in the vicinity of genes encoding selenocysteine-containing formate dehydrogenases in the genome of Methanococcus vannielli and M. maripaludis (Self et al., 2004).

Homologs of mtoX are present in a wide range of bacteria, and metagenomes from marine pelagic, coastal, hydrothermal and terrestrial environments, including DMS stable isotope probing experiments of soil and lake sediment samples. On the basis of processes that contribute to MT production in marine and terrestrial environments, a wide distribution of this enzyme is not surprising. The diversity of mtoX-containing organisms present in the environment is currently not well represented by isolated organisms, which suggests that the ability to degrade MT is more widely distributed than currently realized. This lack of environmentally relevant model bacteria limits our ability to appreciate which organisms are important as sinks for MT in different environments, how the expression of MTO in these organisms is regulated and which other degradative capabilities they may have. Using a stable isotope probing approach with 13C2-DMS, we recently identified Methylophilaeceae and Thiobacillus spp. as DMS-degrading bacteria in soil and lake sediment (Eyice et al., 2015). The finding of mtoX genes in representatives of Thiobacillus and Methylophilaceae is consistent with the role that MT has as a metabolic intermediate in previously characterized DMS-degrading bacteria such as Thiobacillus spp. and adds further weight to the suggestion that certain Methylophilaceae have the metabolic potential to degrade DMS. The detection of mtoX in a saltmarsh environment is in agreement with such environments being hotspots of organic sulfur cycling (Steudler and Peterson, 1984; Dacey et al., 1987) based on production of DMSP and DMS by benthic microalgae, macrophytes and macroinvertebrates (Otte et al., 2004; Van Alstyne and Puglisi, 2007), and MT production through anaerobic processes in the sediment (Lomans et al., 2002).

Overall, this study adds to our fundamental understanding of a key step in the sulfur cycle. The identification of the gene encoding this enzyme reveals its homology to a protein superfamily of which homologs are present in organisms ranging from bacteria to humans, but for which only sketchy functional information has been reported previously. The outcomes of this study will therefore facilitate future investigations of the role of MTO homologs in a wide range of organisms by providing testable hypotheses regarding its physiological relevance in these organisms. At the same time, the identification of the gene encoding MTO as well as its metal dependence will provide key foci for investigation of the diversity and distribution of MTO and potential constraints on its activity such as metal availability on MT degradation rates in the environment as well as aspects of the catalytic mechanism of MTO.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sue Slade for mass spectrometry analyses, Rich Boden for providing Thiobacillus strains and DNA, Colin Murrell and Julie Scanlan for providing M. capsulatus (Bath), Lisa Stein for supplying Methylocystis sp. ATCC 49242 and technical support from Diego Gianolio at DIAMOND Synchrotron. We gratefully acknowledge the help of Joachim Reimann identifying the potential copper ligands and TTQ forming amino acids and producing Supplementary Figures S10 and S11. We are also grateful for funding that supported this study which came from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant reference BB/H003851/1) to HS and TDHB, a Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) Advanced Fellowship (NE/E013333/1) and project grant (NE/H008918/1) to HS, beam time support from DIAMOND Synchrotron (SP8769) to HS, NM, TJS and SJG; NERC project grants (NE/J01138X/1, NE/P012671/1 and NE/M004449/1) to JDT; a grant supporting KKA’s work from the Research Council of Norway (grant no. 214239); a PhD stipend from the University of Warwick to ÖE; and an ERC Advanced grant 669371 (VOLCANO) to HJMOdC.

Author contributions

HS, HJMOdC, NM, AP, KKA, TJS, SJG, JDT, TDHB and AWBJ designed the research; OE, NM, OC, JDT, TJS, SJG, MASHM-K, AP, HS, KKA, AC and SM performed the research; HS, JDT, TJS, KKA, AWBJ, AP and HJMOdC wrote the paper with editorial help of co-authors.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Antholine WE, Kastrau DHW, Steffens GCM, Buse G, Zumft WG, Kroneck PMH. (1992). A comparative EPR investigation of the multicopper proteins nitrous-oxide reductase and cytochrome-c-oxidase. Eur J Biochem 209: 875–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awano S, Koshimune S, Kurihara E, Gohara K, Sakai A, Soh I et al. (2004). The assessment of methyl mercaptan, an important clinical marker for the diagnosis of oral malodor. J Dent 32: 555–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal MP, Oborn CJ, Danielson KG, Medina D. (1989). Evidence for two selenium-binding proteins distinct from glutathione peroxidase in mouse liver. Carcinogenesis 10: 541–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann P, Baumann L (1981). The Marine Gram Negative Eubacteria: Genera Photobacterium, Beneckea, Alteromonas, Pseudomonas and Alcaligenes. In: Starr MP, Stolp H, Trüper HG, Balows A, Schlegel HG (eds). The Prokaryotes. Springer: Berlin, pp 1302–1331..

- Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. (2004). Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol 340: 783–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley R, Chasteen TG. (2004). Environmental VOSCs - formation and degradation of dimethyl sulfide, methanethiol and related materials. Chemosphere 55: 291–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden R, Kelly DP, Murrell JC, Schäfer H. (2010). Oxidation of dimethylsulfide to tetrathionate by Methylophaga thiooxidans sp. nov.: a new link in the sulfur cycle. Environ Microbiol 12: 2688–2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden R, Borodina E, Wood AP, Kelly DP, Murrell JC, Schäfer H. (2011). Purification and characterization of dimethylsulfide monooxygenase from Hyphomicrobium sulfonivorans. J Bacteriol 193: 1250–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrión O, Curson ARJ, Kumaresan D, Fu Y, Lang AS, Mercade E et al. (2015). A novel pathway producing dimethylsulphide in bacteria is widespread in soil environments. Nat Commun 6: 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacey JWH, King GM, Wakeham SG. (1987). Factors controlling emission of dimethylsulfide from salt marshes. Nature 330: 643–645. [Google Scholar]

- Devos M, Patte F, Rouault J, Laffort P, Gemert LJ (1990). Standardized Human Olfactory Thresholds. IRL Press: Oxford, UK..

- Eyice Ö, Namura M, Chen Y, Mead A, Samavedam S, Schäfer H. (2015). SIP metagenomics identifies uncultivated Methylophilaceae as dimethylsulfide degrading bacteria in soil and lake sediment. ISME J 9: 2336–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyice Ö, Schäfer H. (2016). Culture-dependent and culture-independent methods reveal diverse methylotrophic communities in terrestrial environments. Arch Microbiol 198: 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figurski DH, Helinski DR. (1979). Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 76: 1648–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillat MF. (2014). The FUR (ferric uptake regulator) superfamily: diversity and versatility of key transcriptional regulators. Arch Biochem Biophys 546: 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemetakis E, Agalou A, Kavroulakis N, Dimou M, Martsikovskaya A, Slater A et al. (2002). Lotus japonicus gene Ljsbp is highly conserved among plants and animals and encodes a homologue to the mammalian selenium-binding proteins. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 15: 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González JM, Mayer F, Moran MA, Hodson RE, Whitman WB. (1997). Sagittula stellata gen. nov., sp. nov., a lignin-transforming bacterium from a coastal environment. Int J Syst Bacteriol 47: 773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould WD, Kanagawa T. (1992). Purification and properties of methyl mercaptan oxidase from Thiobacillus thioparus TK-m. J Gen Microbiol 138: 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez D, Tewhey R, Veyrieras J-B, Farinelli L, Østerås M, François P et al. (2014). De novo finished 2.8 Mbp Staphylococcus aureus genome assembly from 100 bp short and long range paired-end reads. Bioinformatics 30: 40–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard EC, Henriksen JR, Buchan A, Reisch CR, Buergmann H, Welsh R et al. (2006). Bacterial taxa that limit sulfur flux from the ocean. Science 314: 649–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T, Ishii Y, Yamada H, Oguri K. (2002). The induction of hepatic selenium-binding protein by aryl hydrocarbon (Ah)-receptor ligands in rats. J Health Sci 48: 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jamba L, Nehru B, Bansal MP. (1997). Redox modulation of selenium binding proteins by cadmium exposures in mice. Mol Cell Biochem 177: 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaim W, Schwederski B, Klein A (2013). Bioinorganic Chemistry - Inorganic Elements in the Chemistry of Life: An Introduction and Guide, 2nd edn, vol. 2. Wiley: Chichester, UK..

- Kettle AJ, Rhee TS, von Hobe M, Poulton A, Aiken J, Andreae MO. (2001). Assessing the flux of different volatile sulfur gases from the ocean to the atmosphere. J Geophys Res Atmos 106: 12193–12209. [Google Scholar]

- Kiene RP. (1988. a). Dimethyl sulfide metabolism in salt marsh sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 53: 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kiene RP, Capone DG. (1988. b). Microbial transformations of methylated sulfur compounds in anoxic salt marsh sediments. Microb Ecol 15: 275–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene RP, Linn LJ, Gonzalez J, Moran MA, Bruton JA. (1999). Dimethylsulfoniopropionate and methanethiol are important precursors of methionine and protein-sulfur in marine bacterioplankton. Appl Environ Microbiol 65: 4549–4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S-J, Shin H-J, Kim Y-C, Lee D-S, Yang J-W. (2000). Isolation and purification of methyl mercaptan oxidase from Rhodococcus rhodochrous for mercaptan detection. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng 5: 465–468. [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. (2001). Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 305: 567–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H et al. (2007). Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics23: 2947-2948.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee H-H, Kim S-J, Shin H-J, Park J-Y, Yang J-W. (2002). Purification and characterisation of methyl mercaptan oxidase from Thiobacillus thioparus for mercaptan detection. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng 7: 375–379. [Google Scholar]

- Lomans BP, Smolders AJP, Intven LM, Pol A, Op Den Camp HJM, Van Der Drift C. (1997). Formation of dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol in anoxic freshwater sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 63: 4741–4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomans BP, Maas R, Luderer R, Op den Camp HJ, Pol A, van der Drift C et al. (1999. a). Isolation and characterization of Methanomethylovorans hollandica gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from freshwater sediment, a methylotrophic methanogen able to grow on dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol. Appl Environ Microbiol 65: 3641–3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomans BP, Op den Camp HJ, Pol A, van der Drift C, Vogels GD. (1999. b). Role of methanogens and other bacteria in degradation of dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol in anoxic freshwater sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 65: 2116–2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomans BP, Luderer R, Steenbakkers P, Pol A, van der Drift C, Vogels GD et al. (2001). Microbial populations involved in cycling of dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol in freshwater sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 67: 1044–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomans BP, van der Drift C, Pol A, Op den Camp HJM. (2002). Microbial cycling of volatile organosulfur compounds. Cell Mol Life Sci 59: 575–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig W, Strunk O, Westram R, Richter L, Meier H, Yadhukumar et al. (2004). ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1363–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IM, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. (2009). IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 25: 2271–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monzani E, Quinti L, Perotti A, Casella L, Gullotti M, Randaccio L et al. (1998). Tyrosinase models. Synthesis, structure, catechol oxidase activity, and phenol monooxygenase activity of a dinuclear copper complex derived from a triamino pentabenzimidazole ligand. Inorg Chem 37: 553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte ML, Wilson G, Morris JT, Moran BM. (2004). Dimethylsulphoniopropionate (DMSP) and related compounds in higher plants. J Exp Bot 55: 1919–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pol A, Renkema GH, Tangerman A, Winkel EG, Engelke UF, de Brouwer APM et al (2017). Mutations in SELENBP1, encoding a novel human methanethiol oxidase, cause extra-oral halitosis. Nat Genet (in review). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pol A, Op den Camp HJM, Mees SGM, Kersten MASH, van der Drift C. (1994). Isolation of a dimethylsulfide-utilizing Hyphomicrobium species and its application in biofiltration of polluted air. Biodegradation 5: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porat A, Sagiv Y, Elazar Z. (2000). A 56-kDa selenium-binding protein participates in intra-Golgi protein transport. J Biol Chem 275: 14457–14465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisch CR, Moran MA, Whitman WB. (2011. a). Bacterial catabolism of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP). Front Microbiol 2: 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisch CR, Stoudemayer MJ, Varaljay VA, Amster IJ, Moran MA, Whitman WB. (2011. b). Novel pathway for assimilation of dimethylsulphoniopropionate widespread in marine bacteria. Nature 473: 208–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossen L, Shearman CA, Johnston AWB, Downie JA. (1985). The nodD gene of Rhizobium leguminosarum is autoregulatory and in the presence of plant exudate induces the nodA,B,C genes. EMBO J 4: 3369–3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch DB, Halpern AL, Sutton G, Heidelberg KB, Williamson S, Yooseph S et al. (2007). The Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling expedition: Northwest Atlantic through Eastern Tropical Pacific. PloS Biol 5: 398–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer H, McDonald IR, Nightingale PD, Murrell JC. (2005). Evidence for the presence of a CmuA methyltransferase pathway in novel marine methyl halide-oxidising bacteria. Environ Microbiol 7: 839–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer H. (2007). Isolation of Methylophaga spp. from marine dimethylsulfide-degrading enrichment cultures and identification of polypeptides induced during growth on dimethylsulfide. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 2580–2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer H, Myronova N, Boden R. (2010). Microbial degradation of dimethylsulphide and related C1-sulphur compounds: organisms and pathways controlling fluxes of sulphur in the biosphere. J Exp Bot 61: 315–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self WT, Pierce R, Stadtman TC. (2004). Cloning and heterologous expression of a Methanococcus vannielii gene encoding a selenium-binding protein. IUBMB life 56: 501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon EI, Sundaram UM, Machonkin TE. (1996). Multicopper oxidases and oxygenases. Chem Rev 96: 2563–2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Zou H, Chang Y, Xu W, Wu L. (2006). The cDNA cloning and mRNA expression of a potential selenium-binding protein gene in the scallop Chlamys farreri. Dev Comp Immunol 30: 265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steudler PA, Peterson BJ. (1984). Contribution of gaseous sulfur from salt marshes to the global sulfur cycle. Nature 311: 455–457. [Google Scholar]

- Sun SL, Chen J, Li WZ, Altintas I, Lin A, Peltier S et al. (2011). Community cyberinfrastructure for advanced microbial ecology research and analysis: the CAMERA resource. Nucleic Acids Res 39: D546–D551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suylen GMH, Large PJ, Vandijken JP, Kuenen JG. (1987). Methyl mercaptan oxidase, a key enzyme in the metabolism of methylated sulfur-compounds by Hyphomicrobium EG. J Gen Microbiol 133: 2989–2997. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28: 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangerman A, Winkel EG. (2007). Intra- and extra-oral halitosis: finding of a new form of extra-oral blood-borne halitosis caused by dimethyl sulphide. J Clin Periodontol 34: 748–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd JD, Curson ARJ, Kirkwood M, Sullivan MJ, Green RT, Johnston AWB. (2011). DddQ, a novel, cupin-containing, dimethylsulfoniopropionate lyase in marine roseobacters and in uncultured marine bacteria. Environ Microbiol 13: 427–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd JD, Kirkwood M, Newton-Payne S, Johnston AWB. (2012). DddW, a third DMSP lyase in a model Roseobacter marine bacterium, Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3. ISME J 6: 223–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulshöfer VS, Flock OR, Uher G, Andreae MO. (1996). Photochemical production and air-sea exchange of carbonyl sulfide in the eastern Mediterranean sea. Mar Chem 53: 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Vallenet D, Belda E, Calteau A, Cruveiller S, Engelen S, Lajus A et al. (2013). MicroScope—an integrated microbial resource for the curation and comparative analysis of genomic and metabolic data. Nucleic Acids Res 41: D636–D647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Alstyne KL, Puglisi MP. (2007). DMSP in marine macroalgae and macroinvertebrates: distribution, function, and ecological impacts. Aquat Sci 69: 394–402. [Google Scholar]

- Wang YT, Graichen ME, Liu AM, Pearson AR, Wilmot CM, Davidson VL. (2003). MauG, a novel diheme protein required for tryptophan tryptophylquinone biogenesis. Biochemistry 42: 7318–7325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittenbury R, Phillips KC, Wilkinson JF. (1970). Enrichment, isolation and some properties of methane-utilizing bacteria. J Gen Microbiol 61: 205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Bingemer HG, Georgii H-W, Schmidt U, Bartell T. (2001). Measurements of carbonyl sulfide (COS) in surface seawater and marine air, and estimates of the air-sea flux from observations during two Atlantic cruises. J Geophys Res Atmos 106: 3491–3502. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.