Abstract

Background. Malignant pleural effusion (MPE) is a common complication in most malignancies. Despite its frequent occurrence, current knowledge of MPE remains limited and the effect of the management is still unsatisfying. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) external treatment has unique advantages, such as quicker efficacy and fewer side effects. Objective. To observe the effects and safety of Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment (TCM herbal ointment) in MPE. Design. This was a placebo-controlled double-blinded randomized study. A total of 80 patients were enrolled, of which 72 were randomized to receive Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment or placebo at an allocation ratio of 1:1. Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment or placebo was applied on the thorax wall for 8 hours daily. The intervention lasted 2 weeks. Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment consisted of Astragalus membranaces (黄芪), Semen pharbitidis (牵牛子), Cassia twig (桂枝), Pericarpium arecae (大腹皮), Curcuma zedoary (莪术), Borneol (冰片), and other substances. In both groups, diuresis and drainages were used as needed. Outcomes covered the quantity of pleural effusion evaluation, TCM Symptom Scale, Karnofsky Performance Scale, and safety indicators such as routine blood test, blood biochemistry test, and response table of skin irritation. Results. Of 72 patients randomized to receive Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment or placebo along with symptomatic treatment, the response rate was documented as 42.4% for the treatment group and 25.0% for the placebo group (P = .138). As for the TCM symptom scale, the treatment group showed improvement in chest distress (P = .003), fullness and distention (P = .042), shortness of breath (P < .001), no statistical significance in palpitation (P = .237), and pain (P = .063), whereas the placebo group did not show statistical significance in any of the 5 symptoms. Major adverse events related to the treatment, mainly skin irritation, were distributed equally. Conclusions. Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment showed a potential of reducing MPE, and it could alleviate symptoms of dyspnea. Thus, it may be appropriate as a supplementary intervention for MPE. There were some flaws in the study design. A larger scale and better designed trial is advocated.

Keywords: malignant plural effusion, traditional Chinese medicine, external treatment, palliative treatment, RCT

Introduction

Malignant pleural effusion (MPE) is an important complication for patients with intrathoracic and extrathoracic malignancies. In the United States, more than 175 000 people are affected by MPE annually; the figure in the United Kingdom is 40 000. It is estimated that up to 50% of patients with metastatic malignancy will develop a pleural effusion.1,2 The presence of an MPE portends a poor prognosis, with median survival ranging from 3 to 12 months.3 Furthermore, MPE severely impairs patients’ quality of life (QoL) and shortens their survival.4 Physicians must always be clearly aware that MPE usually indicates an incurable stage of cancer. Despite great advances in cancer treatment in the past decades, management for MPE remains palliative. The usual treatment options are (a) observation while awaiting treatment response to underlying malignancy, (b) repeated thoracentesis, (c) pleurodesis, (d) indwelling pleural catheter placement, and (e) palliation of symptoms with opioids and oxygen in terminal patients.1-5 The therapeutic goals of MPE treatment should not only be fluid removal but also symptom relief (especially from breathlessness), improvement in QoL, and maximizing time outside of hospital.5 Because most procedures are confined by limitations and complications, strategies for MPE management should be made with deliberation.

External treatment is an important technique with a long history and extensive application in broad disciplines in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). It has been applied in MPE and other complications of malignancies for several years.6-13 In the past decade, TCM external treatment has been successfully used in malignancy complications in our clinical practice. Meanwhile, studies of external treatment for cancer complications showed promising outcomes.14-17 Some studies showed that Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment, a TCM herbal ointment of external treatment, had some effect on decreasing MPE.16,17 The aim of this study was to observe the effect of Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment on MPE, in the hope that it could provide some higher level evidence for external treatment in MPE.

Methods

Design

This study was a multicenter, parallel, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. It was aimed to observe the safety and efficacy of Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment, a TCM herbal ointment for external treatment on MPE.

Ethics

The trial was performed with the approval of the Ethics Committee of China-Japan Friendship Hospital for Drug/Instrument Clinical Researches (2013-36). All patients signed an informed consent form before randomization and treatment.

Participants

A total of 80 patients were enrolled, of which 72 were randomized to receive Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment or placebo in an allocation ratio of 1:1.

Eligible patients had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (a) patients with malignant tumor confirmed by pathology or cytology; (b) patients with pleural effusion detected by sonogram or X-ray; (c) cancer cells can be found from subjects’ pleural effusion sample or subjects diagnosed with pleural metastasis; (d) no history of intraperitoneal chemotherapy and/or intraperitoneal immunotherapy within 3 weeks; (e) no severe dysfunction of heart, liver, or kidney; (f) age 18 to 80 years; (g) patients are able to participate in study procedures and QoL evaluations; and (h) patients understand and agree to receive the treatment, and sign information consent form.

Exclusion criteria were the following: (a) patients with skin ulceration or severe hypersusceptibility and (b) patients undergoing radiotherapy/chemotherapy or had radiotherapy/chemotherapy within 1 month.

The subjects were enrolled from 1 of the following 3 centers: China-Japan Friendship Hospital (Center 1), Beijing University of Chinese Medicine Third Affiliated Hospital (Center 2), and Beijing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Center 3).

Outcomes and Response Assessment

Primary outcome was the quantity of pleural effusion evaluation, which was assessed by imagological examination (sonogram or X-ray).18,19 The other primary outcome was TCM Symptom Scale20 (Supplementary Table 1, available online at http://ict.sagepub.com/}supplemental). Secondary outcomes were drainage quantity of pleural effusion/body surface and Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS). There were safety indicators such as routine blood tests, blood biochemistry test, and response table of skin irritation. All indicators were evaluated before enrollment and weekly after randomization. According to maximum of effusion depth, our rating scale defined depth less than 5 cm as Small, 5 cm to 10 cm as Moderate, more than 10 cm as Large. Complete response (CR) was defined as plural effusion having disappeared and symptoms relieved completely. Partial response (PR) was defined as plural effusion having decreased more than 1 grade and symptoms apparently relieved. No change (NC) was defined as no plural effusion decrease and no relief of symptoms. Response was defined as CR + PR.

Intervention

Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment or placebo 10 g was applied on the lateral thorax wall of the effusion side and covered with dressing for 8 hours daily. In both groups, diuresis and drainage were used as needed. The intervention lasted 2 weeks. Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment is a hospital preparation of China-Japan Friendship Hospital. The formula consisted of Astragalus membranaces (黄芪), Semen pharbitidis (牵牛子), Cassia twig (桂枝), Pericarpium arecae (大腹皮), Curcuma zedoary (莪术), Borneol (冰片), and other substances. The placebo composition was starch and pigmentum. It was prepared by the Pharmaceutical Department of China-Japan Friendship Hospital, as was the placebo. The ointment and placebo were packed in sealed identical bottles that contained a supply for about 1 week. The patients were randomized to begin therapy after the enrollment and baseline assessment and after signing the consent form.

Randomization and Blinding

Randomization was used to allocate patients 1:1 to each treatment arm. It was stratified with centers, and with block size of 6. Randomization was made with SAS 9.1.3. Labels with continuous code, which represented randomization and intervention arms, were pasted on the corresponding bottles. Every code had 3 copies of the label pasted on the corresponding bottles. The randomization and codes were kept by an independent personnel blinded to the patients and researchers.

Sample Size Considerations

The sample size calculations were based on the results of previous studies. We assumed that the effect rate of Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment was 60%, while that of placebo was 25%.17 For 80% power with α set at .05, we would need 29 participants in each arm. Considering 20% as the noncompletion rate, the sample size was 35 for each arm.

Statistical Analysis

We used 2-sample t tests or the Wilcoxon test for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. All tests were with a .05 significance level. Statistical analyses were done using SAS software version 9.1.3. A third party (Guoxinzeding International Medical Technology Co, Beijing, China) did the statistical analysis independently.

Results

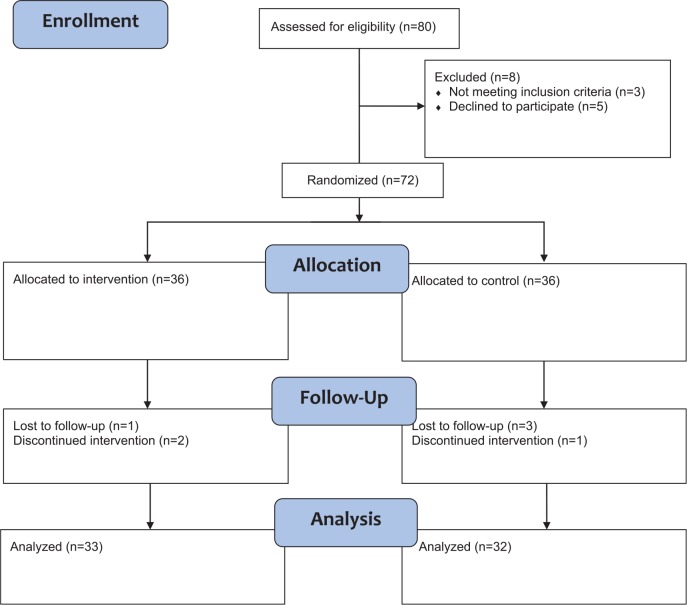

A total of 72 patients with malignancies were randomized. Thirty-seven patients were male. The mean age of the patients was 64.3 (range 40-79) years. The mean disease course was 716.0 days, and the median was 481.0 days. The patients in the 2 groups were well matched for baseline characteristics (Table 1). All patients stayed in the same group as assigned. Of these, 65 were eligible for analysis, 33 of the treatment group and 32 of the placebo group, as shown in the flow diagram in Figure 1. Of the 7 cases of noncompletion, 4 were lost to follow-up. Two ceased due to adverse events, and 1 patient declined the intervention and requested chemotherapy (Supplementary Table 2, available online at http://ict.sagepub.com/supplemental).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Both Study Arms.

| Patients | Treatment, N = 36 | Placebo, N = 36 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 60.0 | 69.0 | .067 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 20 (55.6) | 17 (47.2) | .479 |

| Female | 16 (44.4) | 19 (52.8) | |

| Disease course (days) | 549.9 | 887.4 | .082 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.49 | 22.40 | .064 |

| Disease, n (%) | |||

| Lung | 27 (75.0) | 20 (55.6) | .357 |

| Breast | 3 (8.3) | 5 (13.9) | |

| Digestive tract | 5 (13.9) | 8 (22.2) | |

| Others | 1 (2.8) | 3 (8.3) | |

| Effusion amount (%) | |||

| Large | 8 (22.2) | 3 (8.3) | .210 |

| Moderate | 20 (55.6) | 23 (63.9) | |

| Small | 8 (22.2) | 10 (27.8) | |

| TCM syndrome (none/mild/moderate/severe) | |||

| Palpitation | 16/7/8/5 | 14/15/4/3 | .681 |

| Chest distress | 3/13/19/1 | 4/17/13/2 | .341 |

| Fullness and distention | 7/13/13/3 | 9/11/15/1 | .672 |

| Shortness of breath | 1/11/19/5 | 2/15/13/6 | .406 |

| Pain | 11/16/7/2 | 13/16/3/4 | .625 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Enrollment.

Treatment Outcomes

Of the 72 patients randomized to receive TCM herbal ointment or placebo along with supportive treatment, 65 were eligible for analysis. Twenty-two were reported as PR, 43 were NC, with no CR was reported. The response rate was documented as 42.4% (14/33) in patients receiving TCM herbal ointment and 25.0% (8/32) in those receiving placebo. There was a trend that the treatment group was more effective than the placebo group, but no statistical significance was shown (P = .138; Table 2). However, in relieving symptoms of chest distress, fullness and distention, and shortness of breath, the treatment group showed statistical significance, while the placebo group showed no significant differences in any of the 5 symptoms. Symptoms of heart palpitation and pain in the treatment group showed no statistical significance (Table 3). No thoracentesis/drainage was conducted throughout the treatment. In the treatment group, mean KPS was 69.4 and the median was 70 at baseline. In the last interview, the mean KPS was 71.9 and the median was 70. There was no statistical significance of KPS within the treatment group (P = .277). In placebo group, the mean was 65.3 versus 67.1, and the median was 67.5 versus 70. There was no statistical significance (P = .599).

Table 2.

Response Rate.

| Treatment | Placebo | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 0 | 0 | .138 |

| PR | 14 (42.4%) | 8 (25.0%) | |

| NC | 19 (57.6%) | 24 (75.0%) | |

| LSmean (SE) | −0.305(0.352) | −1.099 (0.408) | .141 (Z = 1.471)a |

| 95% CI | −0.996, 0.385 | −1.899, −0.298 |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; PR, partial response; NC, no change; CI, confidence interval.

P value from Wald test.

Table 3.

TCM Symptomsa.

| Interview 2 (Day 7 ± 1) |

Interview 3 (Day 14 ± 2) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (n = 36) | Placebo (n = 36) | P | Treatment (n = 36) | Placebo (n = 36) | P | |||

| Palpitation | Decrease | 8 (23.5%) | 5 (15.1%) | .794 | Decrease | 8 (26.7%) | 4 (15.4%) | .253 |

| No change | 22 (64.7%) | 26 (78.8%) | No change | 19 (63.3%) | 18 (69.2%) | |||

| Increase | 4 (11.7%) | 2 (6.1%) | Increase | 3 (10.0%) | 4 (15.4%) | |||

| P | .378 | .359 | P | .237 | 1.000 | |||

| Chest distress | Decrease | 12 (35.3%) | 7 (21.2%) | .311 | Decrease | 17 (56.7%) | 6 (23.1%) | .015 |

| No change | 18 (52.9%) | 22 (66.7%) | No change | 11 (36.7%) | 17 (65.4%) | |||

| Increase | 4 (11.8%) | 4 (12.1%) | Increase | 2 (6.7%) | 3 (11.5%) | |||

| P | .077 | .549 | P | .003 | .508 | |||

| Fullness and distention | Decrease | 16 (47.1%) | 3 (9.1%) | .006 | Decrease | 15 (50.0%) | 4 (15.4%) | .013 |

| No change | 15 (44.1%) | 28 (84.8%) | No change | 12 (40.0%) | 17 (65.4%) | |||

| Increase | 3 (8.8%) | 2 (6.1%) | Increase | 3 (10.0%) | 5 (19.2%) | |||

| P | .057 | 1.000 | P | .042 | 1.000 | |||

| Shortness of breath | Decrease | 16 (47.1%) | 6 (18.2%) | .019 | Decrease | 16 (53.3%) | 7 (26.9%) | .031 |

| No change | 16 (47.1%) | 24 (72.7%) | No change | 13 (43.3%) | 17 (65.4%) | |||

| Increase | 2 (5.8%) | 3 (9.1%) | Increase | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (7.7%) | |||

| P | .006 | .508 | P | <.001 | .180 | |||

| Pain | Decrease | 0 | 1 (3.0%) | .431 | Decrease | 7 (23.3%) | 6 (23.1%) | .732 |

| No change | 26 (76.5%) | 26 (78.8%) | No change | 22 (73.3%) | 18 (69.2%) | |||

| Increase | 8 (23.5%) | 6 (18.2%) | Increase | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (7.7%) | |||

| P | .008 | .125 | P | .063 | .289 | |||

Abbreviation: TCM, traditional Chinese medicine.

Comparison between groups: Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Comparison in group: Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Adverse Events

During the intervention, 24 adverse events (AEs) were recorded. There was no severe AE. The comparison of AEs in the 2 groups had no statistical significance (12 vs 12, P = .723). Of all AEs, 9 were considered as related or possibly related to intervention (4 in the treatment group, 5 in the placebo group), most of which were skin irritation or allergy. Two cases led to ceasing the intervention, while the other 7 were merely mild skin reactions. The incidence of intervention related AEs was 12.5% (11.1% vs 13.8%).

Blood routine and biochemical tests showed no statistically significant differences in both groups.

Discussion

Malignant pleural effusion, as a common complication for malignancies, portends a poor prognosis and affects patients’ QoL.3,4 The therapeutic goals of MPE treatment should take fluid removal and symptom relief into account. Despite great advances in cancer treatment, management for MPE remains palliative.1-5

Restricted by complications and some other factors, the management for MPE remains intractable.

This randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled study was performed to investigate the efficacy of Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment, a TCM herbal ointment for external treatment, in dealing with MPE. It was planned to provide some high level of evidence. However, the effect on effusion volume showed no statistical significance between the treatment group and the placebo group, which was not in accordance with the results of previous studies.16,17 After we reviewed the design and process, we found some flaws in the study that might lead to a negative outcome. However, we still consider this study as a meaningful one. So we will pay some attention to discussing those flaws in hopes of helping formulate a better design.

The response rate was documented as 42.4% in the treatment group versus 25.0% in the placebo group, which showed no statistical significance (P = .138). Most probably, this lack of statistical significance is caused by a too small sample size (36 for each arm), as we were overly optimistic in evaluating the effect of the ointment observed in a pilot trial17 for sample size calculation. If we take the data of this study to recalculate sample size, the result will be as follows: set α = 0.05, 1 − β = 0.8, efficiency: 42.4% versus 25.0%, N1 = N2 = 112. If α = 0.05, n1 = n2 = 36, efficiency: 42.4% vs 25.0%, 1 − β = 0.357.

Fortunately, there was no thoracentesis and drainage during the study. In this study, thoracentesis or drainage would be a confounding factor that severely influenced the response, but it was allowed by the protocol, which was a flaw in the study design. To eliminate the confounding, subjects who need thoracentesis or drainage should be excluded.

The protocol allowed using either X-ray or sonogram to evaluate the effusion amount. However, there was no consensus on pleural effusion grading of sonograms. Based on clinical experience and feasibility, a grading criterion was discussed and agreed through a Delphi method by the chiefs of Ultrasonography Departments of all enrollment centers. According to maximum of effusion depth, the grading criterion defined depth less than 5 cm as Small, 5 cm to 10 cm as Moderate, and more than 10 cm as Large.

In this study, the results of evaluation such as CR, PR, or NC were based on the grading criterion mentioned above. This criterion was different from the criterion that is usually used in other studies, and had not been validated. Moreover, the observation period in this study was 14 days, shorter than other studies. Therefore, effect of a longer treatment period remains to be seen. Furthermore, since the treatment goal for MPE includes improvement in QoL and maximizing time outside of hospital, it seems to be more valuable for a future study to observe the duration of effusion decrease, times and drainage or thoracentesis in a certain span of time.

As TCM naturally concerns patients’ subjective feelings, we designed the TCM Symptom Scale. However, the validity of the scale might be weakened. For example, chest distress, fullness and distention, and shortness of breath are 3 TCM symptoms that describe dyspnea from different aspects. They may help TCM doctors with syndrome differentiation and treatment decision. As there was no TCM syndrome differentiation involved, the 3 symptoms could be replaced by dyspnea. Otherwise, patients would be confused. We intended to observe palpitation and pain that was caused by effusion, but confounding of heart disease and cancer pain could not be ruled out.

In consideration of this add-on study design, it would be better to record the disease condition of cancer, which might help identify confounding caused by cancer remission.

Conclusion

Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment showed a potential for reducing MPE and could alleviate symptoms of dyspnea. Thus, it may be appropriate as a supplementary intervention for MPE. There were some flaws in the study design. A larger scale and better designed trial is advocated.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Wu Feize and Liu Meng are co–first authors. This trial was registered at www.chictr.org.cn as ChiCTR-TRC-13003580.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This trial was supported by Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission.

References

- 1. Kastelik JA. Management of malignant pleural effusion. Lung. 2013;191:165-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bennett R, Maskell N. Management of malignant pleural effusions. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:296-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roberts ME, Neville E, Berrisford RG, Antunes G, Ali NJ; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65(suppl. 2):1132-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heffner JE, Klein JS. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of malignant pleural effusions. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2008;83:235-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davies HE, Lee YC. Management of malignant pleural effusions: questions that need answers. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:374-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu L, Lao LX, Ge A, Yu S, Li J, Mansky PJ. Chinese herbal medicine for cancer pain. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6:208-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang B, Hou W, Zhao B, et al. Applications and researches of TCM external treatment on malignant plural effusion. Inf Tradit Chin Med. 2013;12:100-102. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li PW, Tan HY, Wan DG, et al. A herbal ointment of external use for malignant plural effusion: 120 cases clinical study and experimental research. J Tradit Chin Med. 2000;6:358-359. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang X, Chen T. Applications of TCM external treatment on cancer therapies. J Ext Ther Tradit Chin Med. 2008;6:51-53. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zheng L, Wang D, Wu J. Applications of TCM external treatment on postradiotherapy and postchemotherapy treatment. Yunnan J Tradit Chin Med Mater Medica. 2012;11:75-77. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xiao L, He XL, Hu KW, et al. Role of TCM external treatment on malignant tumor therapies. Chin J Basic Med Tradit Chin Med. 2011;2:198-200. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou CH, Bao J, Yin J. Applications of TCM external treatment on malignancy therapies. Guangming J Chin Med. 2009;1:34-35. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang B, Hou W, Du B, et al. Common applications of TCM external treatment in malignancy therapies. Inf Tradit Chin Med. 2013;4:134-137. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jia LQ, Lou YN. Study on external Chinese herbal medicine LC07 treating capecitabine-induced hand-foot syndrome in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15 suppl). Abstract 1088. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sima L, Jia LQ. Study of traditional Chinese medicine LC07 effect on oxaliplatin-induced chronic neurotoxicity. Ann Oncol. 2008;26:431-436. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jia LQ, Li PW, Wei GC, et al. The effect of Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment on malignant plural effusion and its correlation with factor Th1/Th2 in plural effusion. Inf Tradit Chin Med. 2002;12:6-7. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jia LQ, Li PW, Tan HY, et al. A clinical study of Kang’ai Xiaoshui ointment on malignant plural effusion. J Beijing Univ Tradit Chin Med. 2002;4:63-65. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xing W, Ding Y. The X-Ray Differential Diagnosis in Clinical Radiology. Zhenjiang, China: Jiangsu Press of Science and Technology; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shen G, Song ST, Yang WW, et al. The clinical value of ultrasound B on assessing plural effusion amount. Chin J Clin Oncol Rehabil. 2004;1:63-65. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zheng XY. Guiding Principle of Clinical Study on New Medicine Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Beijing, China: Traditional Chinese Medicine Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.