Abstract

Background. Breast cancer patients may experience various symptoms that affect the quality of life significantly and they seek complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). To meet the needs of patients, we developed an integrative outpatient care program. Methods. This program provided CAM consultation and acupuncture for breast cancer patients at Taipei Veterans General Hospital. The outcome measures included Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) and patient satisfaction questionnaires on the first visit (baseline) and at 6 months. Results. Forty-five breast cancer patients were enrolled. All patients completed the study. The median age was 53.3 (±8.3). The symptoms most often experienced during previous cancer treatments were fatigue (35.6%), arthralgia (20%), nausea (6.7%), and insomnia (6.7%). The symptoms most wished to be diminished by the patients were arthralgia (22.2%), insomnia (17.8%), and fatigue (15.6%). Thirty-four patients (75.6%) had sought CAM therapy to reduce these symptoms. Fifteen patients (33.3%) received CAM consultation only and 30 (66.7%) received acupuncture in addition. Sixteen patients completed at least 6 sessions of acupuncture. No serious adverse effect was reported. In the SF-12 Questionnaire on all the patients, physical component summary (PCS) was 49.6 (±5.6) at baseline and 44.9 (±7.6) at 6 months (P = .001); the mental component summary (MCS) was 44.7 (±6.1) at baseline and 52.3 (±9.3) at 6 months (P < .001). For patients who had completed acupuncture, PCS was 49.2 (±4.9) at baseline and 41.4 (±7.6) at 6 months (P = .148); the MCS was 45.6 (±6.2) at baseline and 49.7 (±11) at 6 months (P = .07). Thirty-eight (84.4%) patients were satisfied with this program. Conclusions. Our results demonstrated that an integrative outpatient care program of conventional and Chinese medicine is feasible. Most patients were satisfied with this program and the quality of life was improved. It is important to conduct more research to build a model that integrates CAM with conventional medicine in Taiwan.

Keywords: breast cancer, integrative therapy, traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture, quality of life, complementary medicine

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women in Western countries and in Taiwan.1,2 Accumulated evidence suggests that the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has become increasingly popular among cancer patients.3-6 It is estimated that among breast cancer patients 70% to 80% in non-Asian countries7,8 and 35% in Taiwan have used CAM therapy.9,10 CAM comprises a diverse set of healing philosophies, therapies, and products. Moreover, using CAM to help breast cancer patients relieve their discomforts such as insomnia, hot flushes, cancer-related fatigue, and other symptoms is winning greater acceptance.11,12

Acupuncture, one of the major components of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), has now been widely accepted as a part of CAM therapy.13 Unlike TCM in the Western society, which is defined as alternative medicine, TCM in Taiwan is a government-recognized medical system parallel to modern medicine with regulations and reimbursement by the National Health System. There are 13 Chinese medicine hospitals and 3548 Chinese medicine clinics in Taiwan.14 Most large academic hospitals have also established Chinese medicine departments. However, CAM and conventional medicine are usually provided by different specialists and have not been well integrated in most institutions.

There are 2 models by which integrative oncology may be applied to cancer patients, namely, the expert-based model and the patient-centered model.15 In the expert-based model, a patient seeks medical care first from the oncologists and is then referred to CAM therapists or vice versa. In the patient-centered model, a patient chooses to visit the oncologists/surgeons and CAM providers simultaneously. Most hospitals or medical centers, including those in the Unites States and in Taiwan, adopt the first model for integrative medical therapy. However, the patient-centered model provides friendlier and less time-consuming service for cancer patients. Thus, building a one-step care model that provides CAM and mainstream medicine in the same locale at the same time is essential for establishing a patient-centered integrative therapy for breast cancer patients.

In this article, we share our experience of developing an integrative outpatient care program that provides consultation with surgeons as well as Chinese medicine physicians. Patient satisfaction and quality of life were assessed.

Subjects and Methods

Study Design

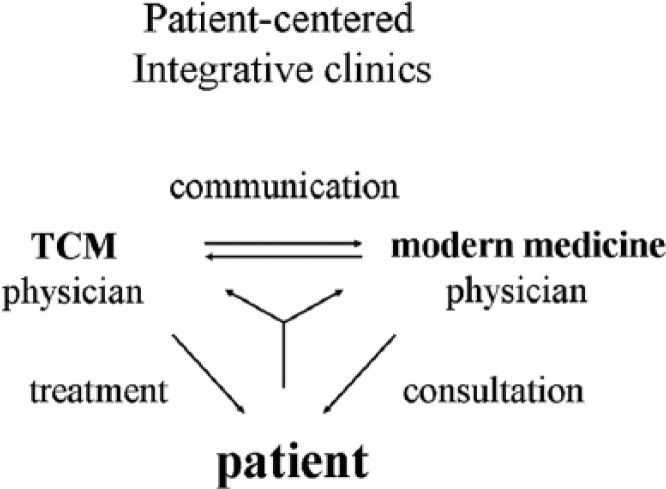

The integrative outpatient care program provides consultation with a surgeon and a Chinese medicine physician jointly regarding the use of CAM, TCM and drug-herb interactions. (Figure 1) Patients may choose acupuncture for the relief of their symptoms. A questionnaire regarding their symptoms, use of CAM, and satisfaction was completed by the patients on the first visit and at 6 months. Outcome measures included Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) and patient satisfaction questionnaire, which were completed by the patients on the first visit and at 6 months.

Figure 1.

A diagram of the one-step patient-centered integrative care program for cancer patients. A modern medicine physician who provides consultation and a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) physician who provides treatment are discussing with a patient in the clinic.

Participants

The study protocol (2101070271C) was approved by the institutional review board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital. Recruitment took place between September 2010 and March 2011. Inclusion criteria were as follows: patients who were diagnosed with breast cancer, aged 25 to 80 years old, and had visited our hospital for integrative outpatient care program. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, pacemaker implantation, history of acute myocardial infarction, non–breast cancer patients, depression, and patients taking Chinese herbal medicine. Voluntary informed consents in written form were obtained from all patients before enrollment. There were 98 breast cancer patients who visited our program, of whom 45 were enrolled.

Interventions

Breast cancer patient who visited the integrative outpatient care program were interviewed by a surgeon and given education materials on complementary/alternative medicine and drug-herb interactions. Patients who were suffering from side effects after surgery and adjuvant treatment had the option of choosing acupuncture. This includes auricle acupuncture, needle acupuncture and electrostimulation performed by a certified Chinese Medicine physician. Acupoints were selected according to the symptoms and the theory of Chinese medicine. Patients with different symptoms were prescribed different acupoints. For instance, the principle for selecting acupoints was as follows: face: S7; shoulder: GB 21, LI 15, SI 11; upper extremities: LI 11, LI 10, TW 5, LI 4; lower extremities: SP 10, ST 36, SP 9, KI 7. Electro-stimulation was applied as either electro-acupuncture (EA), transcutaneous nerve stimulation (TENS) or Silver Spike Point (SSP) therapy. SSP as needle-free EA and has been shown to have a similar analgesic effect to standard EA. Dense-Disperse frequencies (2 and 100 Hz, alternatively) and waves in Silver Spike Point (SSP) were applied to patients to prevent adaption of nerves. A course was defined as six acupuncture sessions and patients had acupuncture 2 to 3 times per week.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures for quality of life included SF-12 and patient satisfaction questionnaire obtained on the first visit (baseline) and at 6 months.16

Statistics

The data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows Version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The distribution and frequency of each category of variables were examined by chi-square tests. A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Population

Forty-five breast cancer patients participated in the integrative care program. All patients completed this program. The median age was 53.3 (±8.3) years. Table 1 shows the patients’ characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics (n = 45).

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median ± SD) | 53.3 ± 8.3 | |

| Stage | ||

| 0 | 1 | 2.2 |

| I | 13 | 28.9 |

| II | 20 | 44.4 |

| III | 11 | 24.4 |

| IV | 0 | 0.0 |

| Therapya | ||

| No therapy | 3 | 6.7 |

| Surgery | 41 | 91.1 |

| Chemotherapy | 28 | 62.2 |

| Radiotherapy | 23 | 51.1 |

| Target therapy | 7 | 15.6 |

| Hormonal therapy | 26 | 57.8 |

| Others | 1 | 2.2 |

| Drugs for hormonal therapy | ||

| Tamoxifen | 13 | 28.9 |

| Anastrozole | 8 | 17.8 |

| Others | 6 | 13.3 |

The patients may receive multiple therapies, so the total percentage exceeds 100%.

Symptoms Presented at First Visit

The patients had filled out a questionnaire regarding their symptoms, use of CAM, improvement, and satisfaction. The symptoms most often experienced during previous cancer treatments were fatigue (35.6%), arthralgia (20%), nausea (6.7%), and insomnia (6.7%). The symptoms most wished to be diminished by the patients were arthralgia (22.2%), insomnia (17.8%), and fatigue (15.6%). Thirty-four patients (75.6%) had previously sought CAM therapy to reduce these symptoms. The prior use of CAM was presented in Table 2. The most often used CAM methods were health food (55.6%), folk herbal remedies (28.9%), massage and aromatherapy (11.1%), acupuncture (8.9%), and energy healing (8.9%). Most health food was provided by nonmedical institutions (42.2%). Most users (33.3%) of health food took it 4 times per month (data not shown). The primary aims for using CAM were to improve immunity (17.8%), reduce side effects (13.3%), and reduce cancer symptoms (13.3%).

Table 2.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Modality Used by Breast Cancer Patients.

| CAM Modality | Providers (Percentage) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance-Contracted Clinics | Regional Hospitals | Medical Centers | Insurance-Noncontracted Clinics | Nonmedical Institutions | Sum | |

| Folk herbal remedies | 8.9 | 2.2 | 8.9 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 28.9 |

| Acupuncture | 4.4 | 4.4 | 8.9 | |||

| Energy healing | 8.9 | 8.9 | ||||

| Relaxation technique | 2.2 | 2.2 | 4.4 | |||

| Health food | 2.2 | 11.1 | 42.2 | 55.6 | ||

| Chiropractic | 4.4 | 4.4 | ||||

| Massage and aromatherapy | 4.4 | 6.7 | 11.1 | |||

| Spiritual healing by others | 4.4 | 4.4 | ||||

| Hypnosis | 0 | |||||

Acupuncture

The reasons for attending the program were to treat insomnia (31.1%), pain relief (26.7%), and consultation (15.6%). The patients were given treatments according to their needs, including consultation, ear magnetic acupuncture, ear acupuncture, manual acupuncture, electroacupuncture, and SSP. Fifteen patients (33.3%) received CAM consultation only while 30 (66.7%) received acupuncture in addition to consultation. Of the 30 who received acupuncture, 16 patients completed at least 6 sessions of acupuncture. Fourteen patients did not complete the course of acupuncture for the following reasons: adverse effects (14.3%), no improvement (7.1%), change to Chinese herbal medicine (7.1%), not willing to continue acupuncture (50.0%), and distant metastasis (7.1%). No serious adverse side effect was reported.

Satisfaction

As to the overall satisfaction with the integrative care program, 39 (86.7%) and 38 (84.4%) patients were satisfied with the program on the first visit and at 6 months. Thirty-nine patients (86.7%) were willing to continue the integrative care on the first visit and at 6 months. If new symptoms were present, 40 patients (88.9%) were willing to receive further treatment in the integrative care program on the first visit and at 6 months. Forty (88.9%) patients would recommend their family and other patients to the program at the first visit while 39 (86.7%) would recommend family and other patients at 6 months.

SF-12 Questionnaire Measurement

In the SF-12 Questionnaire measurement on all the patients, physical component summary (PCS) was 49.6 (±5.6) at baseline and 44.9 (±7.6) at 6 month (p=0.001); the mental component summary (MCS) was 44.7 (±6.1) at baseline and 52.3 (±9.3) at 6 month (P < .001). For the patients who completed acupuncture, PCS was 49.2 (±4.9) at baseline and 41.4 (±7.6) at 6 month (P = .148); the MCS was 45.6 (±6.2) at baseline and 49.7 (±11) at 6 months (P = .07) (Table 3).

Table 3.

SF-12 Questionnaire Measurement at Baseline and 6 Months Afterward.

| PCS1a | MCS1a | PCS2b | MCS2b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 45) | ||||

| Mean | 49.6 | 44.7 | 44.9 | 52.3 |

| SD | 5.6 | 6.1 | 7.6 | 9.3 |

| Patients receiving acupuncture (n = 16) | ||||

| Mean | 49.2 | 45.6 | 41.4 | 49.7 |

| SD | 4.9 | 6.2 | 7.6 | 11.0 |

Abbreviations: SF-12, 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey; PCS, physical component summary of SF-12; MCS, mental component summary of SF-12.

SF-12 at baseline.

SF-12 at 6 months later.

Discussion

In Western society, 5 to 7 steps are required for patients to receive CAM therapy under the guidance of their attending physicians. To our knowledge, this is the first one-step patient-centered integrative care program involving surgeons and TCM physicians for breast cancer patients in Taiwan. The patients can consult with surgeons and receive treatment by TCM physicians simultaneously in the same institution. The joint consultation between surgeon and TCM physician has 2 advantages. The first is that it addresses the issue of the surgeon’s objection to the use of CAM. Second, it enables TCM physicians to better understand the patient’s history and to cooperate with surgeons in conventional cancer treatment.

It is noteworthy that the pattern of integrative cancer therapy in Western society is quite different from those in China and in Taiwan. In Western society, most CAM therapies are paid for out of pocket17 while in China, TCM, which accounts for 90% of CAM, is covered by government insurance.18 Owing to the insurance coverage of dual medical systems, namely, modern medicine and TCM, the latter is not defined as CAM therapy in Taiwan. The most striking difference is the concern of drug-herb interaction. In Western society, more than 50% to 60% of CAM use is prayer or mindfulness meditation and about 10% use herbal products—suggesting the consideration of nonpharmacological approach to integrative oncology.3,19 In contrast, more than 50% to 70% of patients in China and one-third in Taiwan received co-prescriptions of Chinese herbs to treat their breast cancer, with no awareness of potential herb-drug interaction.9,10 There is evidence that many Chinese herbal extracts might upregulate ERα and HER2 gene expression in vitro20,21 and interact with tamoxifen in vivo.22 This program did not include herbal medicine because previous studies indicated that there may be drug-herb interaction between herbal medicine and conventional therapy whereas there is none between acupuncture and conventional therapy. As the program went on, colleagues in the hospital gradually accepted the integrative medicine and began to refer their patients to the program. Consequently, a new integrative care program that provides traditional Chinese herbal medicine is in progress and will enroll more patients.

The findings in our survey showed that most breast cancer patients experienced various symptoms caused by cancer or by cancer treatment. For most patients, the duration between the completion of adjuvant chemo/radiation and their joining this program is no more than three months. There were only a few patients who were still undergoing adjuvant chemo/radiation when entering the program. Most of these patients have tried CAM to resolve these problems, which is consistent with existing studies. To help these patients, the program provides acupuncture in addition to consultation. It is surprising that only 30 patients (66.7%) out of 45 chose acupuncture; yet only 16 received up to 6 sessions of acupuncture. More than half of the patients did not complete the whole course of acupuncture and none dropped out due to severe side effects. In the study by Frisk et al,23 on women with breast cancer and hot flushes, 19/26 (73.1%) patients completed 12 weeks electro-acpuncture to improve health-related quality of life and sleep.23 In the study by Hervik et al,24 59 women suffering from hot flashes following breast cancer surgery and adjuvant treatment (tamoxifen) were randomized to either 10 weeks of traditional Chinese acupuncture or sham acupuncture. All patients completed the study. In the study of Liljegren et al,25 84 patients were randomized to receive either true acupuncture or control acupuncture twice a week for 5 weeks. Seventy-four (88.1%) patients were treated according to the protocol. When compared with other studies, the dropout rate for acupuncture is high in our study. This implies that conventional medicine is still the major medical option for these patients. The patients did not seem to like acupuncture as expected although acupuncture has been practiced in Chinese society for thousands of years. Previous studies show that the prevalence of acupuncture in Taiwan is less than 10%.26 However, there were still 16 patients who went through the whole course and some of them even continued to receive acupuncture up to 6 months. This suggests that some patients may have benefited from acupuncture.

Most patients were satisfied with the program. SF-12 showed improvement significantly at the end of study. Most patients joined this program after they completed conventional cancer treatment, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. There were various symptoms affecting their SF-12 scores. The improvement of SF-12 might be the result of this program. The SF-12 score of the group that completed acupuncture did not show statistical significance. This may be due to small sample size. However, we observed a trend of improvement of MCS, although it was not statistically significant. There are 2 limitations to the acupuncture study. First, improvement in symptoms on the SF-12 scores might be due to the natural progression of recovery after aggressive treatment. Second, the sample size is small. Patients with different symptoms were prescribed with different acupoints. The number of patients with the same symptom is too small to show differences. Previous studies show that acupuncture is effective in relieving nausea/vomiting, hot flush, and pain.13,23-25 In the future, further large scale studies with comparisons to a control group is warranted.

Breast cancer patients who visited the integrative outpatient care program were interviewed by a surgeon and given education materials on complementary/alternative medicine and drug-herb interactions. However, the outcome of the patient education was not collected. According to our understanding, the patients will not use the specific herbs that might interact with the drugs mentioned in our education materials. For instance, herceptin may interact with Radix Angelicae Sinensis, Rhizoma Chuanxiong, Radix Rehmanniae Glutinosae Conquitae, Radix Paeoniae Lactiflorae. Chemotherapy may interact with some food supplements and herbs. Radiation may interact with antioxidants and herbs.

Any specialist could be the physician for the clinic. However, surgeons are the primary caregivers and play a key role in adjuvant treatments for breast cancer patients in Taiwan. A surgeon in the clinic would therefore be invaluable to this program to win the trust and acceptance of other surgeons. This will reduce politics in the hospital and increase patient referrals. As the program progressed, several surgeons and other specialists became interested.

Although Chinese medicine is the traditional medicine in Taiwan, the conventional (Western) medicine has been the mainstream in the medical system for several decades. Most medical centers have set up divisions of TCM. However, Chinese and Western medicines have not been integrated in most hospitals. This is because of the medical education system, regulations, and health insurance coverage. This program is an innovative project designed to provide a patient-centered service and to improve cooperation and mutual understanding of Chinese and Western medicines. Most patients were satisfied with this integrative care program and showed improvement in their quality of life. Our results showed that this program is feasible. Cancer patients often suffer from various problems that cannot be relieved by conventional medicine. However, we should conduct more research to clarify issues such as the indications and benefits of acupuncture, herb use, members of the clinics, and the outcome of patient education. CAM is increasingly becoming more relevant by relieving some symptoms and improving quality of life. It is important to conduct more research to build a model that integrates CAM with conventional medicine in Taiwan.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miss Lin-Jen Tai for her help in collecting the data.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Bureau of Health Promotion. 2007 Annual Report. Taipei, Taiwan: Department of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569-1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Su D, Li L. Trends in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: 2002-2007. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22:296-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ernst E, Cassileth BR. The prevalence of complementary/alternative medicine in cancer: a systematic review. Cancer. 1998;83:777-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boon HS, Olatunde F, Zick SM. Trends in complementary/alternative medicine use by breast cancer survivors: comparing survey data from 1998 and 2005. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leggett S, Koczwara B, Miller M. The impact of complementary and alternative medicines on cancer symptoms, treatment side effects, quality of life, and survival in women with breast cancer-a systematic review. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67:373-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huebner J, Muenstedt K, Prott FJ, et al. Online survey of patients with breast cancer on complementary and alternative medicine. Breast Care (Basel). 2014;9:60-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lai JN, Wu CT, Wang JD. Prescription pattern of Chinese herbal products for breast cancer in Taiwan: a population-based study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:891893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lin YH, Chiu JH. Use of Chinese medicine by women with breast cancer: a nationwide cross-sectional study in Taiwan. Complement Ther Med. 2011;19:137-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wanchai A, Armer JM, Stewart BR. Complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(4):E45-E55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davis SR, Lijovic M, Fradkin P, et al. Use of complementary and alternative therapy by women in the first 2 years after diagnosis and treatment of invasive breast cancer. Menopause. 2010;17:1004-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1444-1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2013 Hospital and Clinic Statistics. Taipei, Taiwan: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cramer H, Cohen L, Dobos G, Witt CM. Integrative oncology: best of both worlds-theoretical, practical, and research issues. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:383142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mandelblatt JS, Bierman AS, Gold K, et al. Constructs of burden of illness in older patients with breast cancer: a comparison of measurement methods. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(6 pt 1):1085-1107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, Bloom B. Costs of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and frequency of visits to CAM practitioners: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2009;(18):1-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li X, Yang G, Li X, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine in cancer care: a review of controlled clinical studies published in Chinese. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60338 Erratum in: PLoS One 2013;8(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kang DH, McArdle T, Suh Y. Changes in complementary and alternative medicine use across cancer treatment and relationship to stress, mood, and quality of life. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:853-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chang CJ, Chiu JH, Tseng LM, et al. Si-Wu-Tang and its constituents promote mammary duct cell proliferation by up-regulation of HER-2 signaling. Menopause. 2006;13:967-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chiu JH, Chang CJ, Wu JC, et al. Screening to identify commonly used Chinese herbs that affect ERBB2 and ESR1 gene expression using the human breast cancer MCF-7 cell line. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:965486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen JL, Wang JY, Tsai YF, et al. In vivo and in vitro demonstration of herb-drug interference in human breast cancer cells treated with tamoxifen and trastuzumab. Menopause. 2013;20:646-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frisk J, Kallstrom AC, Wall N, Fredrikson M, Hammar M. Acupuncture improves health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) and sleep in women with breast cancer and hot flushes. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:715-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hervik J, Mjaland O. Acupuncture for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer patients, a randomized, controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116:311-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liljegren A, Gunnarsson P, Landgren BM, Robeus N, Johansson H, Rotstein S. Reducing vasomotor symptoms with acupuncture in breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant tamoxifen: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135:791-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen FP, Kung YY, Chen TJ, Hwang SJ. Demographics and patterns of acupuncture use in the Chinese population: the Taiwan experience. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:379-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]