Abstract

Purpose. Studies have demonstrated beneficial health effects from yoga interventions in cancer patients, but predominantly in breast cancer. Research on its role in alleviating prostate cancer (PC) patients’ side effects has been lacking. Our primary goal was to determine the feasibility of recruiting PC patients on a clinical trial of yoga while they underwent external beam radiation therapy (RT). Methods. Twice-weekly yoga interventions were offered throughout the RT course (6-9 weeks). Baseline demographic information was collected. Feasibility was declared if 15 of the first 75 eligible PC patients approached (20%) were successfully accrued and completed the intervention. Additional end points included standardized assessments of fatigue, erectile dysfunction (ED), urinary incontinence (UI), and quality of life (QOL) at time points before, during, and after RT. Results. Between May 2013 and June 2014, 68 eligible PC patients were identified. 23 patients (34%) declined, and 45 (56%) consented to the study. 18 (40%) were voluntarily withdrawn due to treatment conflicts. Of the remaining 27, 12 (30%) participated in ≥50% of classes, and 15 (59%) were evaluable. Severity of fatigue scores demonstrated significant variability, with fatigue increasing by week 4, but then improving over the course of treatment (P = .008). ED, UI, and general QOL scores demonstrated reassuringly stable, albeit not significant trends. Conclusions. A structured yoga intervention of twice-weekly classes is feasible for PC patients during a 6- to 9-week course of outpatient radiotherapy. Preliminary results are promising, showing stable measurements in fatigue, sexual health, UI, and general QOL.

Keywords: yoga, prostate cancer, radiation therapy, fatigue, quality of life

Introduction

For most cancer patients, the most common side effects of both the underlying disease and its oncological treatment are pain, depression, and fatigue.1 Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is defined as “a common, persistent, and subjective sense of tiredness related to cancer or to treatment of cancer that interferes with usual functioning.”2 CRF differs from so-called “everyday life” fatigue, which is generally temporary and can be relieved by rest or sleep. The impact of CRF on a patient’s ability to function in daily life is considerable, and it has been found to adversely affect patients’ quality of life (QOL) even more than pain.3-8 Fatigue is reported in 40% to 75% of cancer patients. The prevalence of CRF increases to 60% to 93% in patients receiving external beam radiation therapy (RT),3-5 and when Visual Analogue Fatigue Scales were used, the percentage rose to 99%.9 Furthermore, a significant number of cancer patients suffering from fatigue receive inadequate treatment for their symptoms.1 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that integrative nonpharmacological interventions be implemented for managing CRF. Various studies have demonstrated a positive effect from physical activity interventions during and after cancer treatment. These studies also showed that exercise is safe and well tolerated by patients during various cancer treatments, including RT.1,9-12

Of the estimated 233 000 men who will be diagnosed with prostate cancer (PC) in 2014,13 at least one-third are expected to undergo definitive RT at some point in their lifetimes. In addition to CRF, PC patients typically report high levels of urinary and sexual adverse effects before, during, and after treatment, with more than half of the patients reporting poor sexual drive.14 Erectile dysfunction (ED) is defined by the National Institute of Health as “the inability to achieve or maintain an erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual performance.”15(p. 83) ED is reported in 21% to 85% of PC patients.16-19 The etiology of ED after prostate RT is still poorly understood, with studies demonstrating vascular disease and hemodynamic interference, nerve damage, and or damage to the proximal penile structures.16,18 Urinary incontinence (UI) is a broad term for loss of bladder control from any etiology, with the most common type being stress incontinence caused by loss of outlet resistance at the bladder neck. Urge UI occurs when the bladder detrusor contracts involuntarily during bladder filling and is the more common type of incontinence seen with RT. The prevalence of UI after RT is 24% and may be acute or take years to develop.14,16 The popularity of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been growing rapidly in the general population, with an estimated 70% of Americans currently using some CAM modality.20 Among cancer patients, the prevalence of CAM use has increased nearly 3-fold in the past two decades.21-23 The majority of cancer patients use some form of CAM, hoping to boost immunity, relieve pain, and/or control cancer- and cancer treatment–related morbidity.24 The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines CAM as “a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine” (http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/). Yoga is a physical, mental, and spiritual CAM practice aimed to bring body and mind together. Historically, most research on yoga as a therapeutic modality has been performed in women, and specifically breast cancer patients.25-28 In contrast, research on the use of yoga as a modality for alleviating PC patients’ side effects has been limited.29 Regarding sexual dysfunction and yoga, there are a few published reports in women, but to our knowledge, there are no data on the direct effects of yoga on ED. That said, as one of several mind-body practices, yoga has been demonstrated to elicit a relaxation response characterized by decreased oxygen consumption, increased levels of exhaled nitric oxide (NO), and reduced stress.30 NO is known to play a prominent role in vascular dilation, which affects blood pressure.31 We hypothesize that improving pelvic blood circulation as a result of an increase in circulation blood NO levels may improve ED, although this hypothesis would need to be specifically and prospectively tested with biometric and QOL correlations. With respect to UI, there is some evidence that yoga in combination with pelvic exercise can help reduce this symptom in women. We hypothesized that strengthening of the pelvic floor muscles may reduce UI in PC patients.32,33 The main goal of our study was to evaluate the feasibility of using yoga as a complementary treatment modality in PC patients. We specifically sought to (1) determine if PC patients undergoing a 6- to 9-week course of outpatient RT as definitive or postoperative treatment would consent to participate in the study and comply with attendance of an intensive twice-weekly yoga regimen and (2) study the effect of yoga on fatigue, ED, UI, and general QOL during cancer therapy.

Methods

Participants

Adult men with biopsy-proven PC who consented to undergo a 6- to 9-week course of external beam RT at the University of Pennsylvania were recruited between May 2013 and June 2014. Prospective participants were assessed for eligibility on or before the day of radiation treatment planning (simulation). Patients were prescreened with PAR-Q/PAR-MED-X34 for barriers to participation in physical activity and deemed eligible to participate when they met the following criteria: minimum age of 18 years, biopsy-proven diagnosis of clinical (intact) or pathological (postprostatectomy) stage I or II PC, suitable for a 6- to 9-week course of outpatient RT for PC, and English speaking. Patients were excluded if they, according to their physicians, had medical restrictions that could interfere with or preclude participation in the yoga interventions, were active smokers (former smokers who had been smoke free for the past 6 months or more could be included), currently participated in a yoga practice (any yoga classes on a regular basis within the past 6 months), or had clinical evidence of metastatic disease.

Intervention

Eischens yoga, an integrative style of yoga rooted in the Iyengar practice, is focused more on the energy of the poses rather than the complexity and, thus, is more readily accessible for all body types and experience levels. The hands-on feedback technique helps instructors to continually guide the students, to help them engage the weaker muscles in the body, and to actively improve alignment. This is believed to result in better posture and allow for improved flexibility, greater self-awareness, higher pain tolerance, and increased strength and energy.

Eischens yoga classes were held on several days during the work week (typically late morning and late afternoon) at the Abramson Cancer Center. Each class was led by a trained Eischens yoga instructor, had between 4 and 8 participants, and lasted 75 minutes. A typical session included seated (using a chair), standing, and reclining poses (Table 1). Yoga poses were modified and included the use of props to facilitate and adapt the poses for each participant’s specific needs and restrictions. Each session began with breathing and centering techniques as well as an inventory of energy and stress levels.

Table 1.

Description of Poses.a

| Sitting on Chair | Standing | Reclining |

|---|---|---|

| • Neck and Shoulder Series ° Neck and shoulder side ° Front and back movement ° Shoulder rolls ° Arm movement • Table pose with opposite arm and leg movement • Forward bend (Uttanasana) • Side bend (Parighasana) • Simple chair twist (Bharadvajasana) |

• Mountain pose (Tadasana Samasthithi) • Warrior II series(Virabhadrasana II), • Half-moon variation at the wall (Ardha Chandrasana) Front warrior series |

• Inverted lake pose (Viparita Karani) • Bridge pose variation (Setubandha) • Reclined/seated bound angle pose (Supta Baddhakonasana) • Modified shoulder stand • Big toe posture with a belt (Supta Padangustasana) • Corpse pose (Savasana) |

Patients were required to participate in 80% of offered classes to be considered evaluable.

There were 3 trained teachers available for this pilot study, but 77% of all classes were taught by the lead teacher and study first author, who is a certified Eischens yoga teacher. The remaining 23% of the classes were taught by 2 certified yoga teachers who were trained by the lead teacher in the details of the specific poses to be used for the study participants. Both assistant teachers also had prior experience working with cancer patients.

Assessments

PAR-Q/PAR-MED-X forms were used to assess patients’ eligibility to participate in physical activity; these forms are derived from a 2007 collaboration of international authorities and regional health and fitness organizations seeking to reduce barriers for low- to moderate-intensity physical activity participation and to improve identification of individuals who may require additional screening prior to becoming more physically active. Background and demographic information were collected at the initial meeting, including age, race/ethnicity, marital/partner status, educational history, income, residence location, travel time to facility, method of travel, details regarding comorbidities, disease stage, and details of current radiotherapy.

Fatigue was assessed using the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) questionnaire, a 9-item scale that rapidly assesses fatigue severity. The first 3 questions rate the severity of the patient’s fatigue at its “worst,” “usual,” and “now” over the past 24 hours, with 0 indicating “no fatigue” and 10 indicating “fatigue as bad as you can imagine.” Six questions assess the amount that fatigue has interfered with different aspects of the patient’s life during the past 24 hours. The interference items include general activity, mode, walking ability, normal work (includes both work outside the home and housework), relations with others, and enjoyment of life. The interference items are measured on a 0 to 10 scale, with 0 being does not interfere and 10 being completely interferes. Scores are simple sums of the items in each subscale.

General QOL was assessed using the FACT-G (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General), a 27-item validated instrument measuring symptoms or problems associated with malignancies across 4 scales: physical well-being (7 items); social/family well-being (7 items); emotional well-being (6 items); and functional well-being (7 items). Patients rate all items using a 5-point rating scale ranging from not at all to very much. The measure yields information about total QOL as well as information about the dimensions of physical well-being and disease-specific concerns. FACT-G takes about 5 minutes to complete and has been written at the sixth grade level.

The International Index of Erectile Function Questionnaire (IIEF-5), also referred to as the Sexual Health inventory for Men, was used to assess ED. Scores range from 0 to 25, with scores >21 indicating normal erectile function and scores <12 indicating moderate to severe ED. The International Prostate Symptom Score Sheet (IPSS) was used to determine the severity of urinary symptoms. Scores on this scale range from 0 to 35, where a score of 8 to 19 indicates moderately symptomatic and 20 to 35, severely symptomatic. The final question on this scale addresses urinary QOL and is assigned a score of 1 to 6, where 6 is terrible.

BFI forms were completed by patients at the following time points:

within 2 to 3 weeks prior to start of radiotherapy—that is, on the day of consultation or on the day of simulation;

biweekly while receiving radiotherapy; and

within a week of the last yoga class or at the end of the EBRT course.

FACT-G, IIEF-5, and IPSS forms were completed by patients at the following time points:

within 2 to 3 weeks prior to start of radiotherapy—that is, on the day of consultation or on the day of simulation;

in the fourth week of radiotherapy (when treatment-related symptoms are expected to peak); and

within a week of the last yoga class or at the end of the EBRT course.

Statistical Considerations

This present study was designed as a single-arm longitudinal pilot study of QOL measures, with a sample of 15 participants for feasibility, to be followed by a larger randomized study. We specifically aimed to achieve this goal of 15 out of the first 75 patients approached because this represented an evaluable patient rate of 20%. We hoped to detect 80% participation in the study intervention, defined as twice-weekly yoga class attendance throughout the entire radiation course. An observed 80% participation in 15 patients gave us 80% power to reject 50% or less participation using a 1-sided test at α = .05. Analyses were conducted using Stata v13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX.). Secondary analyses examined the trends over time for QOL measures. Cross-tabulation and summary statistics were used to make illustrations. We determined significance of trends and differences using random effects regression (longitudinal regression using mixed models, fitted by maximum likelihood), treating time point as a categorical indicator and the baseline measure as reference group.35

Results

The main goal of this feasibility study was to evaluate the willingness of patients with PC to participate in a structured twice-weekly yoga regimen concurrent with active cancer therapy. A total of 68 eligible PC patients were approached regarding this study after they agreed (but before they started) to undergo a course of therapeutic external beam radiation. Patient demographics are summarized in Table 2. Of the 68 patients approached, 23 (34%) declined to participate in the study. The most common reasons provided for declining participation were lack of time and incompatibility with work schedules, rather than a lack of interest or “belief” in yoga. Of the 45 remaining patients who consented to the study, 18 (40%) were withdrawn from the study early voluntarily by the principal investigator because of insufficient class attendance. The most common cause cited for inadequate class attendance was an unavoidable and unanticipated conflict between the radiation treatment time and the yoga class schedule (15 of the 18; 83%). Of the remaining 27 patients, 12 (30%) patients participated in 50% or more of the classes, and 15 (59%) finished the required number of yoga classes and were ultimately deemed evaluable by the clinical protocol criteria. The successful completion of the study by 15 patients out of the first 68 approached met our predefined protocol definition of a feasible intervention, and thus, feasibility was declared.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 45) | Evaluable (n = 15) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | .77 | ||

| Mean | 66 | 66.4 | |

| Range | 46-76 | 51-74 | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | .14 | ||

| White | 31 (68.9%) | 11 (73.3%) | |

| Black | 11 (24.4%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Asian | 3 (6.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Marital/Domestic relationship status, n (%) | .79 | ||

| Married/Domestic partner, n (%) | 35 (77.8%) | 11 (73.3%) | |

| Divorced | 6 (13.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Single | 4 (8.9%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Annual income, n (%) | .602 | ||

| <$40 000 | 5 (11.1%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| $40 000-$80 000 | 18 (40.0%) | 8 (53.3%) | |

| >$80 000 | 17 (37.8%) | 5 (33.3%) | |

| Declined to comment | 5 (11.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Education level, n (%) | .207 | ||

| High school graduate | 14 (31.1%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| College graduate | 15 (33.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | |

| Master’s or doctoral degree | 14 (31.1%) | 8 (53.3%) | |

| Declined to comment | 2 (4.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Travel time to facility, n (%) | .223 | ||

| <1 hour | 26 (57.8%) | 10 (66.7%) | |

| >1 hour | 19 (42.2%) | 5 (33.3%) | |

| Patient disease status, n (%) | .909 | ||

| Intact | 37 (82.2%) | 13 (86.7%) | |

| Postoperative | 8 (17.8%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Type of radiation treatment, n (%) | |||

| Proton | 30 (66.7%) | 9 (60.0%) | |

| IMRT | 11 (24.4%) | 4 (26.7%) | |

| Both | 4 (8.9%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Baseline IIEF, n (%) | |||

| Severe ED | 14 (31.1%) | 4 (26.7%) | |

| Moderate ED | 3 (6.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Mild to moderate ED | 10 (22.4%) | 5 (33.3%) | |

| Mild ED | 6 (13.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Normal | 9 (20.0%) | 3 (20.0%) | |

| Declined to comment | 3 (6.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | |

Abbreviations: IIEF, International Index of Erectile Function Questionnaire; ED, erectile dysfunction; IMRT, Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy.

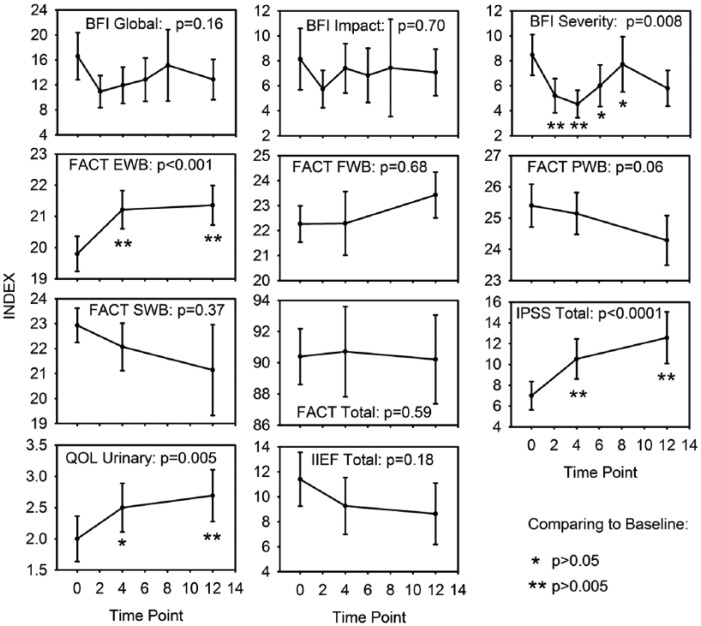

We have summarized the data across all time points in Figure 1. The measures were highly correlated within subject. BFI scales were correlated among time points, with ρ ranging from 0.6 to 0.7. FACT scales were slightly lower, ranging from 0.34 to 0.81. IPSS, QOL, and IIEF-5 gave ρ values of 0.87, 0.84, and 0.78, respectively. The measures were also correlated with each other, averaging 0.41 among measures.

Figure 1.

Quality-of-life measures recorded across prostate cancer treatment in conjunction with Yoga. Sample is 13 to 15 patients at most time points. Bars are 1 standard error (SE). SEs understate separation because of high within-subject correlation.

Abbreviations: BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; FACT, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; EWB, Emotional Well-Being; FWB, Functional Well-Being; PWB, Physical Well-Being; SWB, Social/Family Well-Being; IPSS total, International Prostate Symptom Score; QOL urinary, quality of life associated with urinary symptoms; IIEF-5 Total, International Index of Erectile Function.

Fatigue

Figure 1 shows all 3 measures of fatigue (BFI–severity, BFI–impact and BFI–global). The global fatigue scores (Figure 1) show a slight downward trend in the graph, with fatigue scores staying in the low to midrange levels, but the model was not significant (P = .16). When looking at the impact of fatigue on daily life (Figure 1), variation was also nonsignificant (P = .7). Nevertheless, the severity of fatigue scores demonstrate a significant variability over time over the course of treatment (P = .008; Figure 1). Scores declined over the first 3 weeks but returned to their prior levels by weeks 6 and 8.

Function and Quality of Life

Sexual health scores (IIEF-5) fell slightly over the course of treatment, but the variation among time points was not significant. The IPSS increased sharply over the course of treatment (P < .0001), with significant differences from baseline at 4 and 12 weeks. QOL scores associated with urinary symptoms increased over the course of treatment (P = .005), with significant changes at weeks 4 and 8. Functional, physical, and social well-being parameters showed no significant changes from baseline. Emotional well-being increased from baseline to 4 weeks and 12 weeks (P < .001).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first published pilot study demonstrating the feasibility of an intensive yoga intervention for patients with PC undergoing outpatient radiotherapy. Two-thirds of the men approached were initially very enthusiastic and willing to take part in the yoga program. However, almost entirely because of conflicts between the radiation treatment times and the available yoga class schedule, one-third of the patients who started the program were unable to attend the requisite minimum number of yoga classes. Resource limitations in terms of staffing and room availability restricted the number and timing of yoga classes offered. Radiation treatment machine malfunction leading to unpredictable delays, severe inclement weather, and long travel time to and from the hospital were among the main issues that prevented enrolled patients from attending the twice-weekly classes offered at the hospital. But even despite these issues, the study met our stringent definition of feasibility in this pilot study, in which we mandated a 20% rate of evaluable patients. Typical clinical trial enrollment rates among cancer patients have historically been reported to be as low as 3%36; our rate of enrollment was a surprising 66%, despite the prevailing perception that “old men don’t do yoga.” According to a published national survey of yoga practitioners, we estimate that a little less than 7% of the adult yoga practitioner population comprises men older than 44 years.37-39 Even after removing the study patients who had to be withdrawn early for noncompliance, our rate of enrollment of eligible patients was nearly 40%. Furthermore, we found that all the selected Eischens yoga poses were well tolerated by this patient population and were approached with good will and, at times, a good sense of humor. Most yoga participants reported a sense of well-being at the end of each class; on finishing the yoga program and concluding their involvement in the study, many patients requested and received an at-home practice routine to fit their needs.

Thus far, we have also observed the potential for improvement of CRF with this yoga intervention for PC patients undergoing active radiation treatment. The levels of fatigue that are normally expected to increase midtreatment (weeks 4 to 5) stayed unchanged, and the severity of the fatigue—the ability to lead normal work and social lives—went to pretreatment levels. These results are consistent with early studies that demonstrated the ability of yoga interventions to reduce fatigue symptoms in breast cancer survivors.27

Albeit from nonrandomized data, our findings demonstrate a potential positive signal for improvement in urinary symptoms in patients undergoing radiation treatment for PC. Although the severity of the urinary symptoms expectedly increased during the course of RT, the QOL associated with urinary symptoms stayed unchanged, with lower scores at the range of “pleased to mostly satisfied.” Regarding male sexual health, with the exception of 1 patient who reported no ED, most patients had mild-moderate (IIEF-5 12-16) or moderate (IIEF-5 8-11) ED. At present, we can only report stability in sexual function among those participating in the yoga intervention during radiation treatment. Further follow-up and comparison with non-yoga-participating controls are necessary. Overall, QOL parameters were maintained throughout the treatment, with the exception of a statistically significant decline in emotional well-being. This initial decline (weeks 1 to 4) stabilized with the continuation of the yoga sessions. Because most patients reported a sense of well-being at the end of each class, one hypothesis is that the emotional burden of daily radiation treatments was harder to overcome during the first half of radiation treatment, but its negative effect decreased, and emotional well-being stabilized as patients became increasingly proficient with their yoga practice.

There are several limitations to the present study. The small sample size of this pilot study and lack of a control arm negates the ability to exclude an argument that the findings were caused by a placebo effect. Furthermore, this study was not designed to follow the participants’ sustainability with any structured yoga practice and subsequently measure the long-term effects (over a period of 1 to 3 years) of RT on ED and UI and, thus, QOL. Finally, attention and social support from other group members and/or instructors may have biased the treatment effect and may have added to the overall mental and emotional well-being of the participants.

Fortunately, because our pilot feasibility criteria have been met, this study has continued seamlessly to a randomized phase II design. Future analysis of data from the full complement of yoga and non–yoga participants in the randomized phase of the study will permit more detailed evaluation of the impact of a yoga intervention on fatigue, UI, ED, and overall QOL. Until then, our study does strongly suggest that PC patients, a population perhaps not traditionally believed to have great interest in integrative and complementary therapies because of stereotypes of age and gender, may in fact prove to be a viable and attractive audience for such targeted interventions. At a minimum, the preliminary work presented here underscores the fact that PC patients have a clinically and emotionally significant need for symptomatic management of fatigue and pelvic floor compromise during cancer therapy and that nonmedical approaches should be considered in this setting.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by an American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant.

References

- 1. Patrick DL, Ferketich SL, Frame PS, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science conference statement: symptom management in cancer: pain, depression, and fatigue. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1110-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mock V, Atkinson A, Barsevick A, et al. NCCN practice guidelines for cancer-related fatigue. Oncology. 2000;14:151-161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, Jean-Pierre P, Morrow GR. Cancer related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist. 2007;12(suppl 1):4-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Henry DH, Viswanathan HN, Elkin EP, Traina S, Wade S, Cella D. Symptoms and treatment burden associated with cancer treatment: results from a cross-sectional national survey in the U.S. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:791-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roberto S, Abriani L, Beccaglia P, Terzoli E, Amadori S. Cancer related fatigue: evolving concepts in evaluation and treatment. Cancer. 2003;98:1786-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Poulson MJ. The art of oncology: when the tumor is not the target. Not just tired. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4180-4181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thomas J, Beinhorn C, Norton D, Richardson M, Sumle SS, Frankel M. Managing radiation therapy side effects with complementary medicine. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2010;8:65-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Servaes P, Verhagen C, Bleijenberg G. Fatigue in cancer patients during and after treatment: prevalence, correlates and interventions. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:27-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mustian KM, Morrow GR, Carroll JK, Figuero-Moseley CD, Jean-Pierre P, Williams GC. Integrative nonpharmacologic behavioral interventions for the management of cancer-related fatigue. Oncologist. 2007;12:52-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cramp F, Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD006145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knols R, Aaronson NK, Uebelhart D, Fransen J, Aufdemkampe G. Physical exercise in cancer patients during and after medical treatment: a systematic review of randomized and controlled clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3830-3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ingram C, Visovsky C. Exercise intervention to modify physiologic risk factors in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23:275-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Cancer Institute. SEER State Fact Sheet: Prostate, 2011 National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Panel. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2012. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. Accessed October 29, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kyrdalen AE, Dahl AA, Hernes E, Smastuen MC, Fossa SD. A national study of adverse effects and global quality of life among candidate for curative treatment for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2013;111:221-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. NIH Consensus Conference. Impotence: NIH consensus development panel on impotence. JAMA. 1993;270:83-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mirza M, Griebling TL, Kazer MW. Erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence after prostate cancer treatment. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011;27:278-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burnett AL, Aus G, Canby-Hagino ED, et al. Erectile function outcome reporting after clinically localized prostate cancer treatment. J Urol. 2007;178:597-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown MW, Brooks JP, Albert PS, Poggi MM. An analysis of erectile function after intensity modulated radiation therapy for localized prostate carcinoma. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007;10:189-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wagner W, Bolling T, Hambruegge C, Hartlapp J, Krukemeyer MG. Patients’ satisfaction with different modalities of prostate cancer therapy: a retrospective survey among 634 patients. Anticancer Res. 2011;31;3903-3908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richardson MA, Sanders T, Palmer JL, Greisinger A, Singletary E. Complementary/alternative medicine use in a comprehensive cancer center and the complications for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2505-2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thomas J, Beinhorn C, Norton D, Richardson M, Sumler SS, Franke M. Managing radiation therapy side effects with complementary medicine. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2010;8:65-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yates JS, Mustian KM, Morrow GR, et al. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer patients during treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:806-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swarup AB, Barrett W, Jazieh AR. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:468-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mansky PJ, Wallerstedt DB. Complementary medicine in palliative care and cancer symptoms management. Cancer J. 2006;12:425-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vadiraja HS, Rao MR, Nagarathna R, et al. Effects of yoga on quality of life and affect in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trail. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17:274-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Danhaur SC, Mihalko SL, Russell GB, et al. Restorative yoga for women with breast cancer: finding from a randomized pilot study. Psychooncology. 2009;18:360-368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bower JE, Gare D, Sternlieb B. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: results of a pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hwang JH, Chang HJ, Shim YH, et al. Effects of supervised exercise therapy in patients receiving radiotherapy for breast cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2008;49:443-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carlson LE, Speca M, Faris P, Patel KD. One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcome of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast cancer and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:1038-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dusek JA, Otu HH, Wohlhueter AL, et al. Genomic counter-stress changes induced by the relaxation response. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dusek JA, Benson H. Mind-body medicine: a model of the comparative clinical impact of the acute stress and relaxation responses. Minn Med. 2009;92(5):47-50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim GS, Kim EG, Shin KY, Choo HJ, Kim MJ. Combined pelvic muscle exercise and yoga program for urinary incontinence in middle-aged women. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2015;12:330-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huang AJ, Jenny HE, Chesney MA, Schembri M, Subak LL. A group-based yoga therapy intervention for urinary incontinence in women: a pilot randomized trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20:147-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thomas S, Reading J, Shephard RJ. Revision of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q). Can J Sport Sci. 1992;17:338-345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Education Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Drug Discovery, Development, and Translation. Transforming Clinical Research in the United States: Challenges and Opportunities: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ross A, Friedman E, Bevans M, Thomas S. National survey of yoga practitioners: mental and physical health benefits. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21:313-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. NAMASTA: North American Studio Alliance. http://www.namasta.com/pressresources.php#8. Wellness Industry Data and Statistics; July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015;74:1-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]