Abstract

Purpose. Dyspnea is a common and distressing symptom for patients with lung cancer (LC) because of disease burden, therapy toxicity, and comorbid illnesses. Acupuncture is a centuries-old therapy with biological plausibility for relief of dyspnea in this setting. This pilot study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of acupuncture for dyspnea among patients with LC. Methods. Eligible patients had a diagnosis of LC and clinically significant dyspnea without a clear organic cause. The treatment consisted of 10 weekly acupuncture sessions, with a follow-up visit 4 weeks after therapy. The primary outcome was dyspnea severity as measured using a validated Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) of 0 to 10 (10 being “most severe shortness of breath imaginable”). Results. We enrolled 12 patients in the study. The median age was 64.5 years; 66.7% of the patients were female, and 66.7% were Caucasians. Among those enrolled, 10 (83.3%) were able to complete all 10 acupuncture sessions. Acupuncture was well tolerated; adverse events were mild and self-limited. Mean (SD) dyspnea scores on the NRS improved from 6.3 (1.7) at baseline to 3.6 (1.9; P = .003) at the end of treatment and 3.2 (2.3; P = .008) at follow-up. Fatigue and quality of life also improved significantly with acupuncture (P < .05). Conclusion. Among patients with LC, acupuncture was well tolerated and exhibited promising preliminary beneficial effects in the treatment of dyspnea, fatigue, and quality of life. Performing a trial in this population appears feasible.

Keywords: acupuncture, dyspnea, lung cancer, shortness of breath, supportive care

Background

Lung cancer (LC) is diagnosed in more than 221 000 patients in the United States annually.1 Medical advances have improved survival for LC, but because of disease burden, preexisting illness, and the toxicities of therapy, patients with LC have a significant respiratory symptom burden.2,3 Dyspnea is present in up to 87% of patients with LC and has a profound impact on quality of life and survival.4-8 The existing literature is sparse on interventions to improve dyspnea for patients with LC.9 Physicians also appear to treat the dyspnea associated with LC less aggressively than they do dyspnea associated with chronic lung disease.10 Effective interventions for dyspnea are a clear area of need for patients with LC.

Acupuncture is a component of a 2500-year-old Eastern medical system and is used by more than 2 million adults annually in the United States. Multiple studies have shown acupuncture to be safe when administered by trained practitioners.11-13 A recent systematic review has revealed significant efficacy of acupuncture for a variety of cancer-related symptoms.14 Although the exact mechanism of action for acupuncture is not fully understood, recent animal and human studies have demonstrated an effect that is mediated in part by endogenous opioid release.15,16 These molecules bind the same opioid receptors engaged by synthetic opioids currently used for dyspnea treatment. In addition, neuroimaging studies suggest that acupuncture stimulation may influence the limbic system,17 a brain region whose activity is known to be modulated by dyspnea.7 Endogenous opioid release and limbic system stimulation provide biological plausibility for the use of acupuncture as a treatment for dyspnea.

As with many other integrative modalities, the scarcity of properly designed and conducted randomized controlled trials is a major barrier to more widespread use.18,19 A single randomized study has evaluated acupuncture for dyspnea, but significant issues limit interpretation of this trial. The amount of acupuncture administered was substandard, and the study combined acupuncture with acupressure.20 To evaluate the potential role of traditional acupuncture for the treatment of dyspnea in LC in a formal manner, we performed a pilot study. The specific aims of this study were (1) to evaluate the feasibility of accruing patients with LC to a trial of acupuncture and (2) to estimate preliminary effect size and safety of the intervention.

Materials and Methods

Study Patient Population

We recruited eligible patients from the thoracic oncology clinics at the Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania. Patients 18 years and older were eligible if they had a diagnosis of LC, a dyspnea severity score of at least 4 on a Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) from 0 to 10 (10 being most severe shortness of breath imaginable), an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 1 to 3 and could provide informed consent and complete study surveys in English. Key exclusion criteria included life expectancy of less than 12 weeks as assessed by the treating oncologist, an organic cause of dyspnea requiring immediate treatment (eg, pleural effusion, acute radiation pneumonitis as measured by treatment with steroids for less than 3 weeks, acutely progressive disease, or severe anemia), or a current bleeding disorder. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participation. This study received approval from the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

Study Intervention

The acupuncture treatment regimen was semistandardized, which has been an effective approach in prior studies of acupuncture.21 The acupuncture points were chosen based on a review of the literature and were further informed by a team of licensed acupuncturists, a palliative care physician, and an oncologist with knowledge of LC treatment. The primary acupuncture points were chosen to improve dyspnea, but additional points were presented as optional in the case of a particular symptom (see Supplemental Table 1 [available at http://ict.sagepub.com/supplemental] for acupuncture points used). The needles (25 or 40 mm and 0.25 gauge, Seirin, Seirin-America Inc, Weymouth, MA) were inserted until the patient reported a sensation of soreness (termed De Qi). Treatments occurred in 2 stages. Patients were first seated in a comfortable chair in the chemotherapy infusion suite to allow the placement of anterior needles. These needles remained in place for 15 to 20 minutes and were then removed. Patients were then placed face down in a massage chair for the placement of posterior needles. These needles were also kept in place for 15 to 20 minutes and then removed. No stimulation of the acupuncture needles was utilized. Patients received weekly treatments for 10 weeks and had a follow-up visit 4 weeks after the end of treatment. This dose of acupuncture has been effective in prior trials.22 Two licensed acupuncturists, each with greater than 10 years of experience, administered the acupuncture.

Data Collection and Outcome Measurement

Patient-reported outcome instruments were utilized to obtain information on symptom severity. Patients completed surveys at baseline, at the end of treatment, and at a follow-up visit 4 weeks after treatment completion.

The primary outcome of the study was dyspnea severity in the past 7 days, as measured by a Dyspnea NRS. Scores on the NRS ranged from 0 (no shortness of breath) to 10 (most severe shortness of breath imaginable). NRSs have been used extensively in the measurement of dyspnea and are responsive to change.23

Given the limitations of unidimensional measurement of a complex symptom such as dyspnea,23 we also used a multidimensional instrument. The Cancer Dyspnea Scale (CDS) was originally written and validated in Japan to assess the effort, anxiety, and discomfort associated with dyspnea24 and has since been validated in English.25 The CDS is structured around 3 domains: sense of discomfort, sense of anxiety, and sense of effort. Scores range from 0 to 49, and a higher score indicates more severe dyspnea. The CDS is the only multidimensional dyspnea assessment tool that is validated in cancer patients, but it has never been used in a clinical trial. Thus, we did not know its sensitivity to change and chose to use the CDS as a secondary outcome measure.

Patients with LC often describe their dyspnea as a feeling of fatigue,26 so we also measured fatigue with the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI).27 The BFI is a validated instrument for the assessment of fatigue among patients with cancer. We also measured global quality of life using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Lung version (FACT-L).28 Each of these validated instruments was utilized at baseline, at the end of treatment, and at the follow-up visit.

To monitor objective findings related to dyspnea severity, we performed spirometry and lung volume measurements in the pulmonary function laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania at baseline and at the end of treatment. In addition, patients completed a 6-minute walk test, which has been validated as a prognostic marker in patients with dyspnea.29

To define the patient’s impression of their dyspnea improvement with acupuncture, we administered the Patient Global Impression of Change instrument30 weekly throughout therapy.

Sample Size Calculation and Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in STATA (STATA v12.1, College Station, TX). For our primary outcome, we used a paired, 2-sided t test to compare the dyspnea severity as measured by NRS at baseline with the score at the end of treatment. Significance was defined at .05. Based on prior studies, the SD of a NRS measuring dyspnea among patients with LC is 2.1.23 We hypothesized that if acupuncture could cause an effect size of 1 SD reduction in dyspnea, we would need 10 individuals to have 80% power to detect such difference, using a 2-sided significance level of .05. We chose a 12-subject sample size to account for an expected loss to follow-up rate of 15%.

To better characterize the effect of acupuncture among patients with LC, we performed a series of paired t tests to compare objective pulmonary measurements and symptom severity at the end of treatment and at the follow-up visit with baseline measurements. All tests were 2-sided, and a significance level of .05 was used. Given our small sample size, these evaluations should be regarded as exploratory.

Results

Participant Characteristics

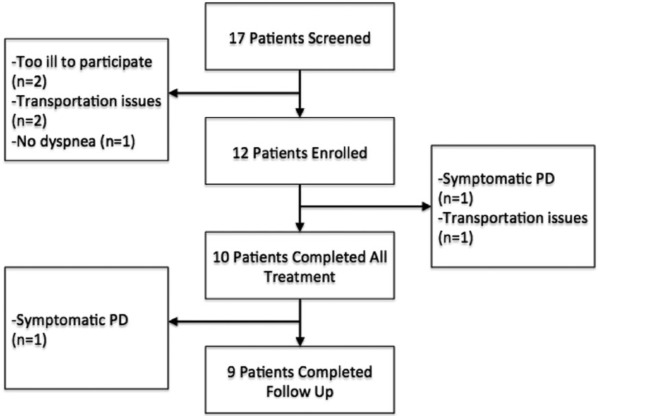

We screened 17 patients to identify the 12 patients who enrolled in our study (see Figure 1). The median age of enrolled patients was 64.5 years, with a SD of 10 years, and 66.7% of patients were female. The racial breakdown of enrolled patients included 66.7% Caucasians, 25% African Americans, and 8.3% Asian Americans. Prior treatment included surgery (25%), radiation therapy (58.3%), and chemotherapy (75%); 33.3% of patients had recurrent/metastatic disease and were receiving active treatment (see Table 1). Of note, all patients who received radiation therapy also received concurrent chemotherapy.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Abbreviations: PD, progressive disease.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics.

| Age, Median (SD) | 64.5 (10) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 8 (66.7%) |

| Male | 4 (33.3%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 8 (66.7%) |

| African American | 3 (25%) |

| Asian | 1 (8.3%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Former smoker | 9 (75%) |

| Never smoker | 3 (25%) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed full time | 2 (16.7%) |

| Not currently employed | 10 (83.3%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 9 (75%) |

| Divorced | 2 (16.7%) |

| Widowed | 1 (8.3%) |

| Initial cancer stage | |

| I | 1 (8.3%) |

| III | 7 (58.3%) |

| IV | 4 (33.3%) |

| Prior surgery | |

| Yes | 3 (25%) |

| No | 9 (75%) |

| Prior radiationa | |

| Yes | 7 (58.3%) |

| No | 5 (41.7%) |

| Prior chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 9 (75%) |

| No | 3 (25%) |

| Recurrent/Persistent disease | |

| Yes | 4 (33.3%) |

| No | 8 (66.7%) |

All patients receiving radiation therapy received concurrent chemotherapy.

Feasibility and Safety

In this study, 83.3% of patients were able to receive all scheduled acupuncture treatments, with only 2 patients unable to attend all sessions. One patient withdrew from the study because of a long commute to the center, and another had progression of LC while on the study and was unable to participate further because of illness. A third patient had progression of disease after the final acupuncture appointment and was unable to attend the follow-up visit. All patients who completed at least 1 acupuncture session were included in the final analysis.

Despite the use of chest wall acupuncture points in a population with a high incidence of emphysema, no patient experienced a pneumothorax. There were no attributable adverse events of grade 2 or higher seen in this study.

There were 3 possibly related or related adverse events noted during >100 acupuncture sessions. There were 2 patients who experienced mild redness/bruising near a needle site, and 1 patient experienced a minor exacerbation of chronic back pain. All adverse events were mild and resolved without intervention.

Improvement in Dyspnea

Mean dyspnea severity (SD) on the NRS was 6.3 (1.7) at baseline, 3.6 (1.9) at the end of treatment, and 3.2 (2.3) at follow-up. There was a statistically significant difference between both later time points and baseline (P = .003 and .008, respectively). There was a 49% reduction in dyspnea severity from baseline to follow-up. This was a clinically significant effect size, correlating with a Cohen’s d of 1.49 at the end of treatment and 1.53 at the follow-up. Scores on the CDS also improved from 12.3 (6.8) at baseline to 7.1 (4.8) at the end of treatment and 6.3 (4.8) at follow-up. This was also a statistically significant difference (P = .04 for both comparisons). There was a numerical improvement in all subscales of the CDS at the end of treatment and at follow-up (see Table 2). At the end of treatment, 60% of patients reported that their dyspnea was at least somewhat better, and at the follow-up visit, 77.8% of patients reported at least some improvement in dyspnea. No patient experienced worsening of dyspnea.

Table 2.

Symptom Scales.

| Symptom Scale | Baseline Mean (SD) | EOT Mean (SD) | p Value | FU Mean (SD) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyspnea NRS | 6.3 (1.7) | 3.6 (1.9)a | .003 | 3.2 (2.3)a | .008 |

| Cancer Dyspnea Scale–Total | 12.3 (6.8) | 7.1 (4.8)a | .04 | 6.3 (4.8)a | .04 |

| Sense of discomfort | 3.8 (1.9) | 2.5 (2.0) | .08 | 2.1 (1.8)a | .01 |

| Sense of anxiety | 3.9 (2.9) | 2.1 (2.0) | .27 | 1.8 (1.8) | .21 |

| Sense of effort | 4.5 (3.2) | 2.5 (2.1)a | .03 | 2.4 (2.3) | .10 |

| FACT-L | 72.4 (20) | 94.4 (17)a | .03 | 95.5 (13) | .07 |

| BFI | 4.8 (2.4) | 2.8 (2.1)a | .05 | 3.6 (2.0)a | .04 |

P value of <.05 when compared with baseline.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; EOT, end of treatment; FU, follow-up; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; FACT-L, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Lung version; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory.

Improvement in Related Symptoms

Overall, participants experienced an improvement in fatigue and global quality of life at the end of treatment. The effect on fatigue maintained statistical significance at the follow-up visit (see Table 2). No statistically significant changes were seen in pulmonary function testing or in 6-Minute Walking Distance (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Pulmonary Function Test Results.

| Variable | Baseline Mean (SD) | EOT Mean (SD) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FVC (L) | 2.0 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.6) | .30 |

| FVC (percentage expected) | 65.3 (14.4) | 67.6 (15.9) | .15 |

| FEV1 actual (L) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.5) | .41 |

| FEV1 (percentage expected) | 60.6 (14.3) | 62.9 (15.5) | .19 |

| 6MWD (feet) | 1017.8 (323.9) | 1026.3 (341.4) | .89 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; EOT, end of treatment; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; 6MWD, 6-Minute Walking Distance.

Discussion

Dyspnea is a distressing symptom that is highly prevalent among patients with LC4-8; mitigating this symptom is a high priority and a clear unmet need. In this pilot study, we demonstrated successful recruitment and retention to a study of acupuncture for dyspnea in LC. There was a statistically and clinically significant improvement in dyspnea, as measured with both the NRS and CDS. At the time of follow-up, nearly 80% of patients reported some improvement in their dyspnea. Acupuncture was well tolerated, and there were no episodes of pneumothorax despite a significant rate of emphysema among patients with LC. In addition to improving dyspnea, acupuncture was also associated with improved fatigue and quality of life.

Although dyspnea is a debilitating symptom, with even mild symptoms leading to significant interruption of normal activities of daily living,26 currently available therapies are inadequate. The current standard of care for dyspnea among patients with advanced cancer is low-dose opioids, which are associated with significant side effects.9 Our study revealed an effect size for acupuncture that was similar to that previously reported for opioids,31,32 with an improved side effect profile for acupuncture. This observation needs to be confirmed in a larger, randomized study.

Dyspnea has previously shown a strong correlation with quality of life and fatigue.33,34 Indeed, for some patients with LC, fatigue and dyspnea represent the same clinical entity.26 Thus, the effect seen in our study on quality of life and fatigue is not surprising. Interestingly, subjective dyspnea severity has historically exhibited poor correlation with expected objective factors predicting degraded lung function. For instance, dyspnea severity is not associated with the extent of LC surgery, and its correlation with pulmonary function tests has been inconsistent.5,35 Therefore, it is not surprising that we were able to see an improvement in dyspnea severity without a change in objective pulmonary measurements. It should be noted, however, that all objective measurements exhibited a numerical improvement. Prior studies of acupuncture for other lung diseases have shown improvement in pulmonary function test measurements.36,37 Our pilot study was not adequately powered to detect a significant improvement.

This study has a number of important limitations. First, the lack of a control group makes it impossible to rule out the possibility of a placebo effect or symptomatic improvement independent of the intervention itself. Whereas prior studies have raised the concern of a placebo response to acupuncture,38 this seems to be mostly limited to sham acupuncture. Prior work by our group has indicated that response expectancy, a key component of the placebo effect, is not a predictor of response to true acupuncture.39 Although we cannot exclude symptomatic improvement independent of the intervention, dyspnea and other symptoms generally worsen over time among patients with LC.2,40 The presence of a significant improvement in dyspnea is, thus, notable. Next, our population was relatively heterogeneous, including patients with cured and active cancer who had received a variety of prior treatments. For instance, some patients became quite ill related to their disease and were unable to complete follow-up. Although this is certainly a limitation, it may reflect a more “real-world” application of acupuncture for dyspnea and would be expected to bias our study toward the null. Finally, our sample size in this pilot trial was small, which, when combined with the heterogeneous population, may limit generalizability of our findings. Our findings should be confirmed in a larger, randomized study.

In spite of these limitations, our study has notable strengths. Dyspnea is a major cause of symptomatic distress for patients with LC,4,8 and currently available therapies for its treatment are inadequate and can have significant toxicities (eg, opioids).9 Acupuncture was well tolerated by a group of patients with LC, and performing a trial in this population was feasible. This was the first trial to use the CDS in the context of a clinical trial, and it seemed to be responsive to change. In conclusion, acupuncture exhibited promising preliminary effects in the treatment of dyspnea. This benefit needs to be confirmed in a larger, randomized controlled study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study. We thank the physicians, nurse practitioners, acupuncturists, and staff for their support. We would like to thank our hardworking students and staff for their dedication to the data collection and management process.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by an institutional research grant awarded from the American Cancer Society to the Abramson Cancer Center (PI Joshua Bauml). The design of this protocol was enhanced through Dr Bauml’s attendance at the ASCO/AACR Methods in Clinical Cancer Research Workshop.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schag CA, Ganz PA, Wing DS, Sim MS, Lee JJ. Quality of life in adult survivors of lung, colon and prostate cancer. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:127-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Degner LF, Sloan JA. Symptom distress in newly diagnosed ambulatory cancer patients and as a predictor of survival in lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:423-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xue D, Abernethy AP. Management of dyspnea in advanced lung cancer: recent data and emerging concepts. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2010;4:85-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dales RE, Belanger R, Shamji FM, Leech J, Crepeau A, Sachs HJ. Quality-of-life following thoracotomy for lung cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1443-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dudgeon DJ, Kristjanson L, Sloan JA, Lertzman M, Clement K. Dyspnea in cancer patients: prevalence and associated factors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:435-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith EL, Hann DM, Ahles TA, et al. Dyspnea, anxiety, body consciousness, and quality of life in patients with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:323-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ben-Aharon I, Gafter-Gvili A, Leibovici L, Stemmer SM. Interventions for alleviating cancer-related dyspnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:996-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Edmonds P, Karlsen S, Khan S, Addington-Hall J. A comparison of the palliative care needs of patients dying from chronic respiratory diseases and lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2001;15:287-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Melchart D, Weidenhammer W, Streng A. Prospective investigation of adverse effects of acupuncture in 97,733 patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:104-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. MacPherson H, Thomas K, Walters S, Fitter M. A prospective survey of adverse events and treatment reactions following 34,000 consultations with professional acupuncturists. Acupunct Med. 2001;19:93-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. White A, Hayhoe S, Hart A, Ernst E. Adverse events following acupuncture: prospective survey of 32 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists. BMJ. 2001;323:485-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garcia MK, McQuade J, Haddad R, et al. Systematic review of acupuncture in cancer care: a synthesis of the evidence. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:952-960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ulett GA, Han J, Han S. Traditional and evidence-based acupuncture: history, mechanisms, and present status. South Med J. 1998;91:1115-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu DZ. Acupuncture and neurophysiology. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1990;92:13-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hui KK, Liu J, Makris N, et al. Acupuncture modulates the limbic system and subcortical gray structures of the human brain: evidence from fMRI studies in normal subjects. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;9:13-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller FG, Emanuel EJ, Rosenstein DL, Straus SE. Ethical issues concerning research in complementary and alternative medicine. JAMA. 2004;291:599-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, Higginson I. Non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness in advanced stages of malignant and non-malignant diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD005623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vickers AJ, Feinstein MB, Deng GE, Cassileth BR. Acupuncture for dyspnea in advanced cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled pilot trial [ISRCTN89462491]. BMC Palliat Care. 2005;4:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mao JJ, Styles T, Cheville A, Wolf J, Fernandes S, Farrar JT. Acupuncture for nonpalliative radiation therapy-related fatigue: feasibility study. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2009;7:52-58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Xie SX, Bruner D, DeMichele A, Farrar JT. Electroacupuncture versus gabapentin for hot flashes among breast cancer survivors: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3615-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bausewein C, Farquhar M, Booth S, Gysels M. Measurement of breathlessness in advanced disease: a systematic review. Respir Med. 2007;101:399-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tanaka K, Akechi T, Okuyama T, Nishiwaki Y, Uchitomi Y. Development and validation of the Cancer Dyspnoea Scale: a multidimensional, brief, self-rating scale. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:800-805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uronis HE, Shelby RA, Currow DC, et al. Assessment of the psychometric properties of an English version of the Cancer Dyspnea Scale in people with advanced lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44:741-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tanaka K, Akechi T, Okuyama T, Nishiwaki Y, Uchitomi Y. Impact of dyspnea, pain, and fatigue on daily life activities in ambulatory patients with advanced lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:417-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer. 1999;85:1186-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cella DF, Bonomi AE, Lloyd SR, Tulsky DS, Kaplan E, Bonomi P. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) quality of life instrument. Lung Cancer. 1995;12:199-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miyamoto S, Nagaya N, Satoh T, et al. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of six-minute walk test in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: comparison with cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(2, pt 1):487-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sloan JA, Aaronson N, Cappelleri JC, Fairclough DL, Varricchio C. Clinical Significance Consensus Meeting Group. Assessing the clinical significance of single items relative to summated scores. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:479-487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mazzocato C, Buclin T, Rapin CH. The effects of morphine on dyspnea and ventilatory function in elderly patients with advanced cancer: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:1511-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bruera E, MacEachern T, Ripamonti C, Hanson J. Subcutaneous morphine for dyspnea in cancer patients. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:906-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Henoch I, Bergman B, Gustafsson M, Gaston-Johansson F, Danielson E. Dyspnea experience in patients with lung cancer in palliative care. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:86-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chan CWH, Richardson A, Richardson J. A study to assess the existence of the symptom cluster of breathlessness, fatigue and anxiety in patients with advanced lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2005;9:325-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bruera E, Schmitz B, Pither J, Neumann CM, Hanson J. The frequency and correlates of dyspnea in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:357-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Martin J, Donaldson AN, Villarroel R, Parmar MK, Ernst E, Higginson IJ. Efficacy of acupuncture in asthma: systematic review and meta-analysis of published data from 11 randomised controlled trials. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:846-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lau KSL, Jones AYM. A single session of Acu-TENS increases FEV1 and reduces dyspnoea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:179-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vickers AJ, Linde K. Acupuncture for chronic pain. JAMA. 2014;311:955-956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bauml J, Xie SX, Farrar JT, et al. Expectancy in real and sham electroacupuncture: does believing make it so? JNCI Monogr. 2014;2014:302-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Muers MF, Round CE. Palliation of symptoms in non-small cell lung cancer: a study by the Yorkshire Regional Cancer Organisation Thoracic Group. Thorax. 1993;48:339-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.