Abstract

Mechanical ventilation is a common life support intervention for critically ill patients that can cause stressful psychological symptoms. Animal assisted interactions have been used in variety of inpatient settings to reduce symptom burden and promote overall well-being. Due to the severity of illness associated with critical care, use of highly technological equipment, and heightened concern for infection control and patient safety, animal-assisted interaction has not been widely adopted in the intensive care unit. This case study of the therapeutic interaction between a canine and a mechanically ventilated patient provides support for the promotion of animal-assisted interactions as an innovative symptom management strategy in the intensive care unit.

Keywords: animal assisted therapy, intensive care unit, critical care, artificial respiration, mechanical ventilation

Introduction

Mechanical ventilation, which requires a patient to be intubated with an artificial airway, is an expensive, high risk intervention that causes a multitude of debilitating psychological symptoms such as anxiety, confusion, agitation, and sleep disturbances.1–9 Animal-assisted interactions (AAI) have been used in a variety of inpatient and outpatient settings to help alleviate patients’ psychological symptoms and promote overall well-being.10,11 However, due to the severity of illness associated with critical care, the use of highly technological equipment, and heightened concern for infection control and patient safety, AAI have not been widely adopted in the ICU. The purpose of this paper is to (1) describe the process and symptoms of mechanical ventilation during critical illness, and (2) highlight, via a factual case presentation, the need for increased use of AAI in the ICU to help patients better manage distressing psychological symptoms during mechanical ventilation.

Background

Mechanical Ventilation

Mechanical ventilation is a life-sustaining intervention commonly used in the ICU to support respiratory insufficiency or failure.12 A variety of ventilator modes and settings specific to the pressure, volume, and oxygen concentration of each delivered breath are used and adjusted by medical staff based on the needs of the patient. Some patients may only temporarily require mechanical ventilation to bridge them through acute critical illness, while others may need mechanical ventilation for an extended period, from several weeks to months.12

Psychological Symptoms Associated With Mechanical Ventilation

Mechanical ventilation further complicates the distressing symptom burden experienced by ICU patients. Common psychological symptoms reported by the critically ill include anxiety, spells of terror, social isolation, nervousness, disturbed sleeping patterns, fatigue, restlessness, fear, and confusion.3–8,13 Unfortunately, these distressing symptoms are often exacerbated during mechanical ventilation because ventilated patients have extremely limited mobility, decreased capacity to communicate, and rely on healthcare providers and medical staff for survival.5,6 Jablonski described the striking awareness some ventilated patients have of their mortality and the range of emotions they experience during their frequent attempts to come to terms with dependence on the ventilator.13 The emotional and psychological stress induced by mechanical ventilation affects patients long after ICU discharge.13 A recent study found that one in three patients who underwent mechanical ventilation showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for up to two years after their hospitalization, and half of those with PTSD symptoms required psychotropic medications.14 The long-term impact of mechanical ventilation can slow patients’ recovery and keep individuals from returning to baseline levels of daily functioning.14,15

Symptom Management During Mechanical Ventilation

Nurses are primarily responsible for managing patients’ symptoms during critical illness.16–18 Due to the immense psychological and physical stress induced by mechanical ventilation, the administration of sedative and analgesic medications is often the first strategy employed by nursing staff.16–18 While the administration of these medications may be necessary to promote comfort, reduce stress, improve ventilator synchrony, facilitate nursing care, and ensure patient safety, overuse of these medications can cause sequelae of negative complications such as hypotension, delirium, fatigue, and extreme muscle weakness. In addition, continuous high doses of these medications can cause long-term issues with memory and cognition as well as problems with depression, anxiety, and paranoid delusions.14,15,18–21 Therefore, the need for these medications should be assessed on an individual, continual basis.18,20,21 Current nursing guidelines instruct nurses to limit the administration of sedative and analgesic medications to “light” levels that will maintain patient comfort but preserve cognitive alertness.21

There is growing evidence that mechanically ventilated patients can benefit from an increased awareness of their environment.4,16,19–23 In a recent study, patients who were most awake and aware of their surroundings during mechanical ventilation had the lowest PTSD-like symptoms after hospital discharge.24 Jablonski13 found patients who had been mechanically ventilated appreciated the symptom relief provided by sedatives and analgesics but expressed reservations about the amnesic effects of these medications and how they interfered with the ability to understand and accept the mechanical ventilator. Additionally, Egerod18 found that ventilated patients struggled to maintain clear thinking due to the sedatives they were receiving. In a recent study by Karlsson et al.,4 eight out of 12 patients would have chosen consciousness over sedation if given the choice.

Animal-Assisted Interactions During Critical Illness

Although the literature supports keeping patients more awake and alert while on the ventilator, distressing symptoms may still persist, and therefore, additional nonpharmacologic symptom management techniques are imperative to promoting psychological well-being during mechanical ventilation.25,26 One of those techniques, Animal-Assisted Interaction (AAI), is defined as “any intervention that intentionally includes or incorporates animals as part of a therapeutic or ameliorative process or milieu.”27 AAI includes any aspect of direct service—inpatient, outpatient, and community settings—in which an active partnership between skilled humans and trained animals promotes human health, learning, and well-being.28 In general, domestic and farm animals such as dogs, cats, birds, equines, guinea pigs, rabbits, llamas, sheep, goats, and pigs are predominantly featured in AAI programs.29 Sessions typically last for 15–30 minutes, depending on the goals of the AAI interaction and the health, safety, and well-being of the animal, handler, and patient. Animals can be simply observed, touched, held, and petted, or more actively integrated into specific therapy activities such as brushing with different tools to exercise range of motion and fine motor coordination and tandem walking with the animal to encourage exercise.30

Current literature indicates that AAI can improve reality orientation and attention span, eliminate the sense of isolation, reduce stress and anxiety, enhance communication, promote positive social interactions, and enhance overall quality of life.10,11,30–32 In a study of 69 patients hospitalized with heart failure (HF), AAI via walking with a dog significantly reduced refusal rates of ambulation and increased the distance, or number of steps taken compared to a historical population of 537 HF patients.33 Another study showed a small sample of participants with physical impairments and functional disabilities who worked with a mobility assistance dog significantly improved their performance on functional mobility tests.34 Finally, Snipelisky and Burton35 found that AAI positively impacts motivation, providing the patient with a renewed sense of determination to recover.

Specific to the ICU, AAI can be used adjunctively to sedative and analgesic medications in order to improve psychological symptoms and promote comfort, relaxation, and positive mood in mechanically ventilated patients. Additional research is warranted to further explore the potential impact of AAI on other clinically meaningful critical care patient outcomes such as delirium rates, hemodynamic parameters, neurohormone levels, and total ICU days. Unfortunately, the highly technical, fast-paced ICU environment often limits meaningful psychological and physical connections for ICU patients, but the use of AAI in the ICU has the potential to engage patients, family members, and healthcare staff through this innovative, holistic approach to symptom management.10,11,21,25,26,30,32,33,35

Case Study

Practice and research literature support the use of AAI (animal-assisted interaction) in the hospital setting. However, limited evidence exists that specifically examines the benefits of AAI in the ICU. 10,11,21,25–26,30,32–33,35 The following case study demonstrates that AAI can be effectively used in the ICU and provides a clinical example of successful AAI with a mechanically ventilated patient.

J.S., a 76-year-old man, entered the ICU following an acute myocardial infarction and subsequent coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Post-operatively, he developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and was unable to tolerate removal of the mechanical ventilator. After two weeks of acute mechanical ventilation, a tracheostomy was surgically placed at the bedside in the ICU to support his need for long-term mechanical ventilation. One week after the tracheostomy was placed, J.S. remained on the ventilator and required only minimal doses of sedative and analgesic medications. However, he did not acknowledge family and staff interaction. Despite direct efforts by family to initiate communication, J.S. kept his eyes closed. Nursing staff noted J.S. appeared to cry silently and demonstrated signs of frustration such as banging the bedrails with his fists. In addition, he would not willingly participate in physical therapy sessions and therapists could only provide J.S. with passive range of motion exercises.

Upon further assessment, ICU staff discovered J.S. had a 5-year-old Golden Retriever dog whom he walked daily prior to his acute illness. J.S.’s family revealed that the dog was very much a focus of his life and often his only companion after his wife died several years prior. After discussion with the palliative care team, an official request was placed with the hospital’s volunteer office to send a trained AAI team to visit J.S. as soon as possible. The following afternoon, the AAI team—a volunteer handler with previous ICU nursing experience and an adult Labrador Retriever dog with three years of volunteer experience—was assigned to work with J.S. The nursing staff introduced the AAI team to J.S. and his family. At first, J.S. refused to open his eyes or acknowledge the team. Nursing staff repositioned J.S.’s bed in an upright, chair position to better facilitate close interaction with the dog. With further encouragement from his family, J.S. opened his eyes. Upon seeing the dog, he smiled and waved. Nursing staff lowered his bedrail, and he willingly reached out to pet the dog. The AAI handler gave J.S. an information card that included the dog’s picture and personal information. J.S. asked for his glasses and even attempted to read the card. After 15 minutes of visiting and interacting with the AAI team, J.S. indicated he was feeling tired but asked that the dog be brought back as much as possible. Subsequent visits with J.S. were arranged, some in conjunction with scheduled physical therapy sessions. At the time of his transfer from the ICU to a general medicine floor two weeks later, J.S. was tossing a toy to the dog, feeding the dog treats, and posing for pictures. Several months later, J.S.’s family wrote a thank-you letter to the staff in the ICU; they mentioned how much J.S. loved dogs and still referenced his time with the AAI team as the most positive memory of his hospital experience.

Discussion

Mechanical ventilation provokes distressing psychological symptoms in critically ill patients. While sedative and analgesic medications can provide symptom relief, nurses are encouraged to limit pharmacologic interventions for symptom management in the ICU when medically appropriate.15–19,21,25,26 AAI should be considered as an appropriate adjunctive treatment to alleviate distressing psychological symptoms while maintaining alertness and promoting social interaction and physical engagement.7,10,11,30–32

Applying the P.A.C.E. Model™ to Animal-Assisted Interactions in the ICU

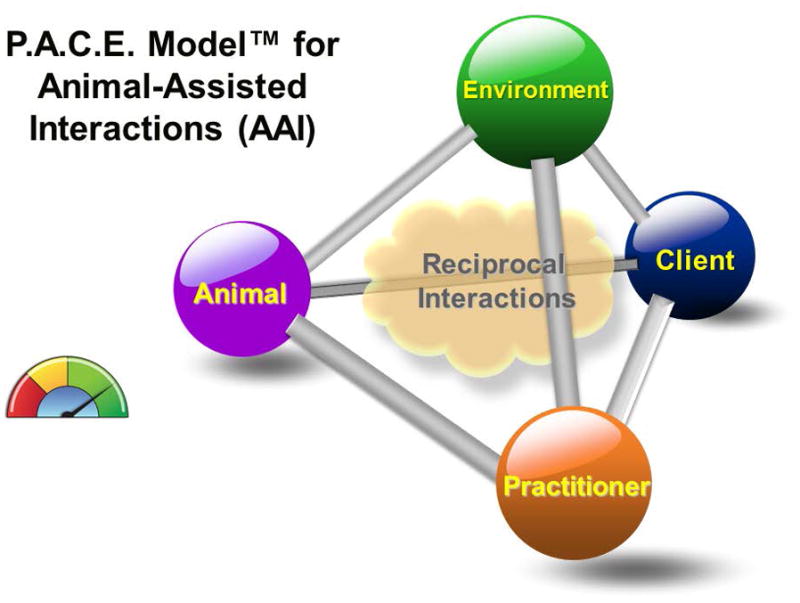

While AAI can have a multitude of positive effects on the patient experience, all those involved in an AAI session must be prepared to adjust to ensure the utmost safety and quality of each interaction. The P.A.C.E. (practitioner, animal, client, and environment) Model™ for AAI29,36 helps to conceptualize the intricate quality of an AAI session by providing a framework to assess rigor, goals and objectives, risk management, and precautions in each AAI session. First, attention is given to the four main program components (See Figure 1) —practitioner, animal, client, and environment—in each dynamic AAI session. Second, the model provides administrators or providers with a “checks and balances” tool to efficiently and effectively assess the design, implementation, and evaluation of each AAI session. The merits of the four P.A.C.E. components must be considered individually, and yet together as well, as they create a reciprocal and evolving relationship that is unique at each session and is identified in the model by connecting lines between each component. Third, each component in the model brings a level of skill and capacity to each AAI session called Quality of Competence (QOC). In Figure 1, the QOC is displayed as a gauge with a plus and minus sign to denote the level of QOC. prior to every AAI session, the four components of QOC are evaluated by both the practitioner and the program coordinator in an effort to eliminate bias and address the relationships between each component. It is important that the program coordinator be involved in the evaluation process because the program coordinator will have information about the environment and client that the practitioner will not know. AAI sessions are strengthened or limited by the QOC and synergy of all four components; it requires both art and science to combine them and create an effective therapeutic experience. The application of the P.A.C.E. Model™ to AAI in the ICU is necessary in order to maintain the integrity of the AAI session for all participants. Table 1 provides considerations of the P.A.C.E. Model™ during AAI sessions in the ICU.

Figure 1.

Table 1.

Considerations of the P.A.C.E. Model™ Specific to the ICU

| Practitioner (Animal Handler) | Animal | Client (Mechanically Ventilated Patient) | Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Should have specific ICU training related to: Technological equipment

|

Consider the size of the animal

|

The following patient factors should be evaluated with input from healthcare staff and/or family caregivers prior to each AAI session: Psychological disposition

|

To ensure safety, it is imperative that healthcare staff participate with animal handler in preparing and maintaining a safe environment. The following is necessary for each AAI session:

|

The practitioner is the identified person who plans, leads, and holds responsibility for his or her AAI sessions. It is imperative that the AAI practitioner and animal share a close, respectful relationship with each other and that the practitioner is attuned to animal behavioral cues that indicate stress, discomfort, or fear. Ultimately, the practitioner must advocate for and ensure the animal’s safety in every session, and is responsible for altering or ending sessions to maintain professional integrity. It is also important that the AAI practitioner has a baseline understanding of the psychophysiological and safety factors related to the environment and the client. In the case study presented, the AAI practitioner had experience as an ICU nurse, and while this is not required, adequate knowledge of the environment and patient experience is critical to anticipate factors that may influence the quality of the AAI session. Typically, in a complex environment like the ICU, there are multiple healthcare practitioners (i.e. nurses, doctors, technicians) who team with the AAI practitioner who has brought the animal. The healthcare team is ultimately responsible for the patient and the AAI practitioner monitors the animal’s welfare and helps guide the AAI session.The animal is the identified animal that is assisting in facilitating AAI services. Best practices dictate that one animal works with one AAI practitioner at a time, especially in medically fragile settings such as the ICU, to ensure exceptional attention and oversight is given to the interaction between the animal and the client. The animal in AAI sessions must have extensive obedience and socialization training, and be capable and well-suited for the goals of each interaction. A well-rounded AAI program will include various breeds of dogs to accommodate varying environmental conditions and client needs; for example, poodles, because they shed fur very little, and may include other, specific animal species, such as rabbits, because they are small and portable.

All AAI sessions start and end with the client in mind. The client is the identified, primary person who is receiving AAI services in either an individual or group setting. It is because of the client’s identified and unidentified needs that the AAI session exists in the first place, and every interaction should be assessed continually.29,36 For example, when the AAI team met J.S. the first time, their visit was subdued, patient, and fairly brief. Towards the end of J.S.’s hospitalization, the AAI team was much more active and deliberate regarding his therapy goals. Secondary clients can also occur and typically involve accompanying caregivers, like the family members who were with J.S. To best support the primary client’s care, the medical team will find it very helpful to include AAI sessions into a client’s treatment plan and develop session objectives and boundaries. Risks will be minimized and the AAI practitioner and animal will have greater success with the primary client by having a clear guide for their sessions.

The most overlooked and underappreciated component is the environment, the identified location where AAI services are held as well as the greater environmental milieu. An AAI session begins as soon as an AAI team gets out of their car, and the AAI team must navigate multiple settings from the time they arrive and depart from a facility. For example, a human-canine AAI team will immediately garner attention by other individuals—staff, patients, visitors —at a healthcare facility. Because animals in AAI programs are not service animals, there is typically no identifying information on the animal signifying a “do not pet” request. As an AAI team enters a healthcare building, they may encounter inconsistent or slick floor surfaces, various loud or high-pitched sounds, changes in temperature, and lingering fumes with acrid or chemical odors, and spaces and hallways containing unfamiliar people dressed in unfamiliar ways. All of these environmental logistics are considerations before an AAI team makes it to their designated session location with the client. Once an AAI team is with the client, new and different logistics can add to the layers of program complexity. As in the case study example, J.S. moved from ICU to general medicine, and each setting is a new treatment environment for an AAI team and requires some level of adjustment with each change. AAI teams must also be mindful of how to balance the primary focus of their visit—supporting a client—with all the secondary requests they may receive from staff, children, and others to spend time with or greet/pet the animal.

AAI sessions are tailored for the goals and objectives of the client, the consistency or ambiguity of the environment, and the experience and training of the practitioner and animal. Furthermore, the process and results created by the four components in the P.A.C.E. Model™ for AAI is reciprocal because each of the components engages with and impacts the other three components, producing a constant give-and-take in each session. As demonstrated in Figure 1, the relationship between each pair of components is signified by a line that can change in length and width to denote the evolving and varying strength and compatibility between each pair of components. For example, the AAI practitioner and animal would share a short line if they have worked together in AAI programs for a lengthy period of time, and a wide line if their bond together as a team was extremely strong. This same practitioner would share a long line with the environment if it was a new hospital setting for the practitioner, and a wide line if the practitioner had considerable experience in other hospitals, and more specifically, ICU environments.

Finally, the four components in the P.A.C.E. Model™ for AAI bring an evolving level of experience and quality of competence (QOC) to each AAI session. In the case study, J.S. initially displayed little motivation to engage with the AAI team at his first session—his QOC was low because he did not know what to expect or how to behave. The QOC of the AAI practitioner was high because of her previous experience in an ICU setting, and the QOC for the AAI animal would ideally be at least midrange, demonstrating a willingness and comfort with meeting new people and intense environments. By the end of his hospital stay, J.S. actively engaged with the AAI team, his healthcare team, and his family, and his QOC in AAI sessions also increased as he gained confidence, health, and strength. J.S. was initially in the ICU, a highly structured and complex environment; the QOC of an ICU setting is high because of the consistency and rigor found in each room—each machine and instrument in the ICU has a predetermined place and all extraneous items are removed to support the patient’s immediate needs. As J.S. recovered and used other healthcare services, the QOC of each environment became more variable. For example, a private physical therapy office has a higher QOC than hospital hallways when a client is working with a dog in an AAI session. Ideally, the four components in the P.A.C.E. Model™ for AAI complement each other, do not produce a deficit in safety, and provide a level of optimal benefit for all those involved in the AAI sessions.

Risk Management With Animal-Assisted Interactions in the ICU

Potential risks associated with AAI should be considered and managed appropriately in the ICU setting.30,37 Due to the severity of illness associated with mechanically ventilated patients, physical concerns such as allergic reactions, physical trauma like scratches and skin tears, as well as the risk of transmission of zoonotic disease between the animal and patient should be evaluated collectively by the healthcare team and AAI practitioner. Each medical facility must ensure sufficient training for AAI teams as well as practice frequent evaluation of AAI practitioner and animal performance. For all hospital consumers—patients, visitors, and staff— education and publicity regarding the benefits of AAI and the use of AAI services at the facility helps support AAI program administration. AAI sessions also offer opportunities to normalize institutional processes such as an ICU; however, inadvertent interaction between the animal and hospital personnel or visitors who do not care to be near animals could evoke distress. Clear policies and procedures for AAI sessions in a hospital ensure proper infection control and promote safety.30,37

Training and education is highly variable for AAI practitioners, and evaluation of AAI teams is a registration process.38 Typically, certain qualifications must be met before a human-animal team is considered a “registered therapy animal” team. Current benchmarks to assess competency include, but are not limited to, a written test, obedience training, veterinarian screening, practicum hours, and experiential evaluations whereby the human-animal team completes a series of exercises to demonstrate skill and aptitude.38 Practitioners are highly encouraged to seek out advanced training, courses, mentorships, internships, and consultation to help guide learning and AAI program development. Hospital administrators are cautioned to rigorously assess and confirm that licensed and credentialed personnel provide AAI services in a respectful and supervised manner. And most important, the welfare, training, comfort, and appropriateness of each animal working in AAI must not be overlooked. Many animals work in AAI programs without advanced training. As sentient beings, each animal brings preferences and inclinations that helps bring balance and stability to AAI, and these unique gifts change over time and with different client populations.

Nursing Implications of Animal-Assisted Interactions With Mechanically Ventilated Patients

As patient advocates and frontline providers of care, nurses play a vital role in facilitating successful AAI sessions. Nurses often have the most intimate knowledge of patients’ personal needs and desires; therefore, they are primed to initiate requests for AAI sessions. By asking patients and families simple questions related to (1) the presence of a pet at home, (2) previous experience with animals, and (3) a desire to interact with an animal in the hospital, nurses can identify whether or not AAI is appropriate for each individual patient. In addition, it is imperative that nurses participate in the preparation of the patient and environment prior to AAI sessions, as well as to continually assess the P.A.C.E. Model™ program components during AAI sessions in order to promote patient participation and safety. Before implementing AAI as a supportive modality in the ICU, the unit leadership should offer training sessions to nursing staff as well as coordinate an introduction to the handlers and their animals in order to encourage the nurses’ familiarization with the AAI teams. It is important to also note the potential benefits of AAI for patients’ family members and the healthcare staff. The animals are often welcome visitors in such a high stress environment. While the patient remains the focus of AAI sessions, the aforementioned benefits of AAI can be easily translated to families and staff through their interactions with AAI teams.

Conclusion

AAI is an effective, useful, and flexible intervention that can be implemented in the ICU with sufficient program planning and oversight. In addition, AAI can be tailored to meet the needs of diverse situations, which makes this therapeutic modality desirable to a vast number of patients, including those undergoing mechanical ventilation. While the current body of research regarding the positive effects of human-animal interactions continues to grow, the specific mechanisms to explain and reinforce how an animal supports human well-being remain a hypothesis in need of further testing. This case study provides a promising example of the potential benefits of animal-assisted intervention (AAI) for patients on mechanical ventilation in the ICU.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This publication was made possible by funding from grant award 4T32NR014213-04 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NINR or the NIH.

Thank you to Dr. Barbara Daly for providing scholarly guidance for this manuscript.

References

- 1.Hayman WR, Leuthner SR, Laventhal NT, Brousseau D, Lagatta JM. Cost comparison of mechanically ventilated patients across the age span. J Perinatol. 2015;35(12):1020–1026. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox CE, Carson SS. Medical and economic implications of prolonged mechanical ventilation and expedited post-acute care. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33(4):357–361. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1321985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamdar BB, Needham DM, Collop NA. Sleep deprivation in critical illness: Its role in physical and psychological recovery. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27(2):97–111. doi: 10.1177/0885066610394322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karlsson V, Bergbom I, Forsberg A. The lived experiences of adult intensive care patients who were conscious during mechanical ventilation: A phenomenological-hermeneutic study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2012;28:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumgarten M, Poulsen I. Patients’ experiences of being mechanically ventilated in an ICU: A qualitative metasynthesis. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29(2):205–214. doi: 10.1111/scs.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engström A, Nyström N, Sundelin G, Rattray J. People’s experiences of being mechanically ventilated in an ICU: A qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2013;29(2):88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tate JA, Devito Dabbs A, Hoffman L, Milbrandt E, Happ MB. Anxiety and agitation in mechanically ventilated patients. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(2):157–173. doi: 10.1177/1049732311421616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puntillo KA, Arai S, Cohen NH, et al. Symptoms experienced by intensive care unit patients at high risk of dying. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(11):2155–2160. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f267ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brummel NE, Girard TD. Preventing delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2013;29(1):51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beetz A, Uvnäs-Moberg K, Julius H, Kotrschal K. Psychosocial and psychophysiological effects of human-animal interactions: The possible role of oxytocin. Front Psychol. 2012;3:234. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamioka H, Okada S, Tsutani K, et al. Effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22:371–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Covidien [Accessed August 8, 2017];What is mechanical ventilation? http://www.livingwithavent.com/pages.aspx?page=Basics/What. Updated 2017.

- 13.Jablonski RS. The experience of being mechanically ventilated. Qual Health Res. 1994;4(2):186–207. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bienvenu OJ, Gellar J, Althouse BM, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: A 2-year prospective longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2013;43(12):2657–2671. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1206–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reade MC, Phil D, Finfer S. Sedation and delirium in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:444–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balas MC, Vasilevskis EE, Burke WJ, et al. Critical care nurses; role in implementing the “ABCDE” bundle: Into practice. Crit Care Nurse. 2012;32(2):35–38. doi: 10.4037/ccn2012229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egerod I. Uncertain terms of sedation in ICU. how nurses and physicians manage and describe sedation for mechanically ventilated patients. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11(6):831–840. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes CG, McGrane S, Pandharipande PP. Sedation in the intensive care setting. Clin Pharmacol. 2012;4:53–63. doi: 10.2147/CPAA.S26582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balas MC, Vasilevskis EE, Olsen KM, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of the Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium Monitoring/Management, and Early Exercise Mobility (ABCDE) Bundle. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1024–1036. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263–306. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta S, Burry L, Cook D, et al. Daily sedation interruption in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients cared for with a sedation protocol: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;308(19):1985–1992. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bassuoni AS, Elgebaly AS, Eldabaa AA, Elhafz AA. Patient-ventilator asynchrony during daily interruption of sedation versus no sedation protocol. Anesth Essays Res. 2012;6(2):151–156. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.108296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulkami AP, Agarwal V. Extubation failure in intensive care unit: Predictors and management. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2008;12(1):1–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.40942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tracy MF, Chlan L. Nonpharmacological interventions to manage common symptoms in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Nurse. 2011;31(3):19–28. doi: 10.4037/ccn2011653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chlan LL. Engaging critically ill patients in symptom management: Thinking outside the box! Am J Crit Care. 2016;25(4):293–300. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2016932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fine AH. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 4. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey T, Christenson G, Lust K. The role of an animal-assisted interaction (AAI) program as a means of reducing stress and anxiety within a college community. Oxford, UK: Inter-Disciplinary Press; In press. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey T. Animal-assisted interactions (AAI): A creative modality to support youth with depression. In: Brooke SL, Myers CE, editors. The use of the creative therapies in treating depression. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 2015. p. 269. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burres S, Edwards N, Beck A, Richards E. Incorporating pets into acute inpatient rehabilitation: A case study. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2016;41(6):336. doi: 10.1002/rnj.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phung A, Joyce C, Ambutas S, et al. Animal-assisted therapy for inpatient adults. Nursing2016. 2017;47(1):63–66. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000504675.26722.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siegel J. Pet ownership and health. In: Blazina C, Boyraz G, Shen-Miller DS, editors. The psychology of the human–animal bond: A resource for clinicians and researchers. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abate SV, Zucconi MA, Boxer B. Impact of canine-assisted ambulation on hospitalized chronic heart failure patients’ ambulation outcomes and satisfaction: A pilot study. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2011;26(3):224–230. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182010bd6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanchet M, Gagnon D, Vincent C, Boucher P, Routhierpeng F, Martin-Lemoyne V. Effects of a mobility assistance dog on the performance of functional mobility tests among ambulatory individuals with physical impairments and functional disabilities. Assistive Technology. 2013;25(4):247–252. doi: 10.1080/10400435.2013.810183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snipelisky D, Burton MC. Canine-assisted therapy in the inpatient setting. Southern Medical Journal. 2014;107(4):265–273. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0000000000000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey T. The P.A.C.E. Model™for animal-assisted interactions (AAI) https://www.scribd.com/document/228227109/Pace-Model-for-Aai-2014. Updated 2014.

- 37.Murthy R, Bearman G, Brown S, et al. Animals in healthcare facilities: Recommendations to minimize potential risks. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(5):495–516. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pet Partners. [Accessed August 8, 2017];Become a Handler. https://petpartners.org/volunteer/become-a-handler/