Abstract

We present evidence from randomized field experiments that 401(k) savings choices are significantly affected by one- to two-sentence anchoring, goal-setting, or savings threshold cues embedded in emails sent to employees about their 401(k) plan. Even though these cues contain little to no marginal information, cues that make high savings rates salient increased 401(k) contribution rates by up to 2.9% of income in a pay period, and cues that make low savings rates salient decreased 401(k) contribution rates by up to 1.4% of income in a pay period. Cue effects persist between two months and a year after the email.

Keywords: nudge, cues, anchoring, goals, 401(k), retirement savings

In this paper, we show using randomized field experiments that seeing subtle cues that make a certain savings choice salient significantly affects individuals’ contributions to their 401(k) retirement savings plan, even though the cues contain little to no marginal information. The design of the three types of cues we test was inspired by psychological phenomena documented in the psychology and behavioral economics literature. Based on this literature, we predicted that savings choices would move towards the choice made salient by each of these cues. Indeed, we find that high savings cues raise 401(k) contribution rates, and low savings cues depress 401(k) contribution rates.

In the terminology of Raiffa (1982) and Thaler and Benartzi (2004), our paper is a work of prescriptive economics, which aims to provide tools to improve economic outcomes. To date, the practice of choice architecture (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008)—a prominent example of prescriptive economics—in retirement savings systems has focused on defaults and the composition of the savings rate and investment option menus (Madrian and Shea, 2001; Benartzi and Thaler, 2001; Thaler and Benartzi, 2004; Huberman, Iyengar, and Jiang, 2004; Huberman and Jiang, 2006; Iyengar and Kamenica, 2010; Beshears et al., 2013). Our results indicate that the salience of particular savings choices is another tool available to the choice architect that is less heavy-handed (and thus potentially less controversial) than changing the default or narrowing the choice menu.

Our field experiments randomized exposure to savings cues in emails about the 401(k) that were sent to one large technology company’s employees in two waves about a year apart from each other: the first in November 2009 and the second in October 2010. The only difference between the control and treatment emails was that the treatment emails included one or two additional sentences. Table 1 gives an overview of the experimental design and cue text.

Table 1.

Experimental design overview

| Cue type | Treatment | Year sent | Eligible population | Cue text added to emails |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Anchor | 1% anchor | 2009 | Employees on pace to contribute $5,000 – $16,499 to 401(k) in 2009 | For example, you could increase your contribution rate by 1% of your income and get more of the match money for which you’re eligible. (1% is just an example, and shouldn’t be interpreted as advice on what the right contribution increase is for you.) |

| 3% anchor | 2010 | Employees on pace to contribute $6,000 – $16,499 to 401(k) in 2010 | For example, you could increase your contribution rate by 3% of your income and get more of the match money for which you’re eligible. (3% is just an example, and shouldn’t be interpreted as advice on what the right contribution increase is for you.) | |

| 10% anchor | 2010 | Employees on pace to contribute $6,000 – $16,499 to 401(k) in 2010 | For example, you could increase your contribution rate by 10% of your income and get more of the match money for which you’re eligible. (10% is just an example, and shouldn’t be interpreted as advice on what the right contribution increase is for you.) | |

| 20% anchor | 2010 | Employees on pace to contribute $6,000 – $16,499 to 401(k) in 2010 | For example, you could increase your contribution rate by 20% of your income and get more of the match money for which you’re eligible. (20% is just an example, and shouldn’t be interpreted as advice on what the right contribution increase is for you.) | |

| Savings threshold | 60% threshold | 2009 | Employees on pace to contribute < $16,500 to 401(k) in 2009 | You can contribute up to 60% of your income in any pay period. |

| $3,000 threshold | 2010 | Employees on pace to contribute < $3,000 to 401(k) in 2010 | The next $x of contributions you make between now and December 31 will be matched at a 100% rate. [x is the difference between $3,000 and the recipient’s year-to-date match-eligible contributions] |

|

| $16,500 threshold | 2010 | Employees on pace to contribute < $3,000 to 401(k) in 2010 | Contributing $y more between now and December 31 would earn you the maximum possible match. [y is the difference between $16,500 and the recipient’s year-to-date match-eligible contributions] |

|

| Savings goal | $7,000 goal | 2010 | Employees on pace to contribute $3,000 – $5,999 to 401(k) in 2010 | For example, suppose you set a goal to contribute $7,000 for the year and you attained it. You would earn $500 more in matching money this year than you’re currently on pace for. |

| $11,000 goal | 2010 | Employees on pace to contribute $3,000 – $5,999 to 401(k) in 2010 | For example, suppose you set a goal to contribute $11,000 for the year and you attained it. You would earn $2,500 more in matching money this year than you’re currently on pace for. |

We call the first type of cues “anchors” (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974) because they mentioned an arbitrary savings increase amount while trying to sound maximally uninformative. Psychologists have long known that the presentation of arbitrary numbers—or anchors—can shift subjects’ judgments and willingness to pay for goods (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974; Johnson and Schkade, 1989; Green et al., 1998; Kahneman and Knetsch, 1993; Ariely, Loewenstein, and Prelec, 2003; Stewart, 2009). However, evidence is only beginning to emerge on the importance of anchoring for economic decisions outside the laboratory (Beggs and Graddy, 2009; Baker, Pan, and Wurgler, 2012; Dougal et al., 2015; Keys and Wang, 2016). Since any cue that makes a particular savings behavior salient is likely to also cause that savings behavior to become an anchor, an anchoring cue can be thought of as a constituent ingredient of all other cues and thus an interesting place to begin the study of cues.1

The second type of cue mentioned a savings threshold that was created by the 401(k)’s employer matching contribution rules or contribution limits. Choi et al. (2002) and Benartzi and Thaler (2007) argue that many people choose their 401(k) contribution rate by using a rule of thumb based on a savings threshold created by the plan’s structure, such as “contribute the maximum possible amount,” or “contribute the minimum necessary to earn the maximum possible employer matching contributions.” Making a certain threshold salient may make an employee more likely to use it as guidance in choosing her contribution rate; a high salient threshold would increase contributions more than a low salient threshold. Threshold-based cues may be more effective than anchors because they leverage these pre-existing rules of thumb. In addition, they are practically useful because they provide a pretext for cueing extremely high savings behaviors that might seem unnatural to mention as an arbitrary anchor without context.

The third type of cue mentioned an arbitrary savings level as an example of a goal. Locke and Latham (1990, 2002, 2006) summarize a large literature showing that setting concrete goals that are difficult to achieve enhances performance relative to setting unambitious or vague “do your best” goals. A number of laboratory studies have found that behavior changes even when the goals are subconsciously primed by cues in the environment rather than consciously chosen (Chartrand and Bargh, 1996; Bargh et al., 2001; Stajkovic, Locke, and Blair, 2006). The goals literature predicts that a high savings goal example will result in higher savings rates than a low savings goal example. Invoking the psychology of goals may be another way to make cues more potent than anchors.

We find that relative to the control email, emails with cues that made a high savings choice salient increased 401(k) contribution rates by up to 2.9% of income in a pay period, and emails that made a low savings choice salient decreased 401(k) contribution rates by up to 1.4% of income in a pay period. Anchors affect average contribution rates with a significant delay, and high anchors have the perverse property of decreasing the probability of making a contribution rate change in the short run. In addition, very high anchors do not raise contribution rates more than moderately high anchors. On the other hand, anchor effects are the most durable out of the cue effects we test, lasting up to nearly a year after the emails were sent. In contrast, threshold and goal cues can have more immediate effects, and they are more effective the further the cue is from the recipient’s status quo, but their effects dissipate within two to seven months.

The cue-induced contribution rate changes we find were unlikely to be financially neutral for individuals. Although we do not observe savings outside the 401(k), the generous employer matching contributions in the particular 401(k) we study means that for most employees, even if each dollar of additional 401(k) contributions was offset by a dollar of decreased saving outside the 401(k), their lifetime wealth would still increase.

Cue effects are interesting not only because they exist, but also because their magnitudes are large compared to those estimated for an expensive, commonly used economic lever to increase 401(k) savings: employer matching contributions.2 Kusko, Poterba, and Wilcox (1998) find that, at one manufacturing firm, increasing the match rate from 25% to 150% on the first 6% of income contributed raised average 401(k) contribution rates by only 0.2% to 0.3% of income. A decrease in the match rate from 139% to 0% was accompanied by an average contribution rate fall of only 0.3% of income. Other studies that identify match effects using across-plan variation come to conflicting conclusions, finding that matches increase, decrease, or have no effect on contributions (see Madrian, 2013, and Choi, 2015, for reviews).

Our findings may provide insight into the mechanisms underlying two important savings phenomena: inertia at the default 401(k) contribution rate, and the clustering of 401(k) contributions at the maximum allowable contribution rate and the employer match threshold (i.e., the maximum level of employee contributions for which the employer will make matching contributions). Although many papers have documented strong savings inertia3, the causes of this inertia are still not fully understood (Bernheim, Fradkin, and Popov, 2015).4 Choi et al. (2002) and Benartzi and Thaler (2007) show that individuals disproportionately contribute at the contribution maximum or the match threshold, but this pattern is consistent with both rational and behavioral explanations. Our experimental results suggest that people frequently end up at the default, match threshold, and contribution maximum in part because those three choices are salient; for example, a 3% default contribution rate inevitably creates a 3% contribution rate cue.

Our treatment effects are estimated on a particular sample of employees—people who are generally highly educated, very well-paid, and technology savvy—in a particular 401(k) plan. However, Goda, Manchester, and Sojourner (2014) describe a field experiment on University of Minnesota employees that shows that cues can be effective in settings that are quite different from ours. Cues are not the main focus of their experiment; they are primarily interested in the effect that providing projections of asset balances and income has on contributions to a supplemental retirement savings plan. But they did randomly vary the graphs used to deliver these projections. One set of graphs showed asset and income projections for the cases where the employees increased their savings by $0, $50, $100, or $250 per pay period. The other set of graphs showed these projections for the cases where the employees increased their savings by $0, $100, $200, or $500 per pay period. Employees receiving the graphs with the higher savings examples had a contribution rate six months after the mailing that was on average 0.2% of income higher than that of those who received the graphs with the lower savings examples. The magnitude of this treatment effect cannot be directly compared to ours because University of Minnesota employees are also covered by a primary pension that mandates high levels of saving, and changing one’s savings rate in the supplemental plan was unusually onerous.5 Our paper is distinguished from Goda, Manchester, and Sojourner (2014) by the fact that we test a greater range of savings cues in a 401(k) whose features are closer to those of a typical plan, and the fact that we are able to observe the dynamics of the contribution rate response rather than outcomes at just one point in time.6

The remainder of our paper proceeds as follows. Section I discusses the features of the company 401(k) plan. Section II describes our data. Section III describes the experimental design for the 2009 email campaign. Section IV analyzes the 2009 experiments. Section V describes the experimental design for the 2010 email campaign, and Section VI analyzes the 2010 experiments. Section VII addresses concerns about multiple hypothesis testing. Section VIII concludes. An online appendix contains details of how the joint hypothesis test in Section VII was implemented and regression tables that correspond to the figures that illustrate most of our results.

I. 401(k) plan features

Employees at the company we study can make before-tax, after-tax, and Roth contributions to their 401(k) plan.7 Before March 2011, employees specified three percentages: the percent of their paycheck they wanted to contribute on a before-tax, after-tax, and Roth basis. Starting in March 2011, employees had the option of specifying a dollar amount rather than a percentage to contribute from each paycheck to each contribution category, although doing so was rare. The sum of the contributions could not exceed 60% of income during any two-week pay period in 2009 and 2010. In 2011, employees could contribute 100% of their paycheck to the 401(k).

Starting in 2007, new hires and seasoned employees who had never enrolled in the 401(k) were automatically enrolled at a 3% before-tax contribution rate unless they opted out. At the beginning of each subsequent calendar year until 2010, seasoned employees who had never actively chosen their 401(k) elections had their before-tax contribution rate automatically increased by 1 percentage point, and the default before-tax contribution rate for new hires also increased by 1 percentage point. In 2011, the default contribution rate for new hires did not change, and seasoned employees were not subject to automatic contribution rate increases.

The company makes matching contributions to the 401(k) that depend upon each employee’s cumulative contributions during the calendar year. The match amount during 2009 was the greater of (1) 100% of before-tax plus Roth contributions up to $2,500, or (2) 50% of before-tax plus Roth contributions up to $16,500, resulting in a maximum possible match of $8,250.8 This match structure generated a 100% marginal subsidy on contributions up to $2,500, a 0% marginal subsidy on contributions between $2,501 and $5,000, and a 50% marginal subsidy on contributions between $5,001 and $16,500. In 2010, the match structure changed to be the greater of (1) 100% of before-tax plus Roth contributions up to $3,000, or (2) 50% of before-tax plus Roth contributions up to $16,500. This new match structure shifted the 0% marginal match zone to contributions between $3,001 and $6,000. Matching contributions vest immediately.

Employees receive an annual bonus that is paid each March. In 2009 and 2010, if an employee had a 5% contribution rate in effect during the pay period in which the bonus was paid, 5% of the bonus would be contributed to the 401(k) plan. As a result, many employees changed their contribution rate shortly before or during the bonus pay period in 2009 and 2010. Starting in 2011, employees could choose a separate contribution election for their bonus, and this election could specify dollar amounts to be contributed rather than percentages of the bonus. Unless actively changed by the employee, the bonus contribution election was by default set equal to the election for regular paychecks.

II. Data description

We use salary and employment termination date data from personnel records and 401(k) contribution rate data from Vanguard. Individuals in the data were assigned random identifiers; no personally identifying information was included.

Vanguard data included cross-sectional snapshots of all 401(k) contribution rate elections (before-tax, after-tax, and Roth) in effect among email recipients on January 3, 2008, November 4, 2009, October 15, 2010, and every month-end from January 2010 to August 2011. We also have a record of every 401(k) contribution rate change from January 3, 2008 to August 31, 2011.9 Vanguard additionally supplied the total dollars contributed to the 401(k) between January 1, 2009 and November 4, 2009 for each 2009 email recipient, and the total dollars contributed to the 401(k) between January 1, 2010 and October 15, 2010 for each 2010 email recipient. This allowed us to calculate how many dollars each employee would contribute to the 401(k) during the calendar year if she left her contribution rate elections unchanged—a variable that determined which treatments the employee was eligible to be assigned to.

III. Design of 2009 experiments: 1% anchor and 60% threshold cues

On November 17, 2009, we sent emails to all employees hired before 2009 who would contribute less than $16,500 on a before-tax plus Roth basis in 2009 if they left their contribution rate elections as of November 4, 2009 unchanged.10 We randomized which email version each employee received. The template used for the 2009 emails is shown in Figure 1. All emails described the matching contributions the company offered and the amount the recipient had contributed so far in 2009. Following this information was the statement, “To take greater advantage of [Company]’s 2009 match, increase your contribution rate for the remaining six weeks of 2009.” The emails concluded with step-by-step directions for changing one’s contribution rate on the Vanguard website and was signed by the company’s benefits director.

Figure 1. 2009 email text.

The 2010 emails’ text followed the same template, except for minor changes noted in the main text of Section V.

The only difference between the control and treatment emails was that the treatment emails included one or two additional sentences right after the statement about taking greater advantage of the match. We began our study of cue effects by exploring the extremes of the state space: the lowest savings rate cue that had a reasonable chance of advancing the company’s goal of increasing 401(k) savings, and a cue that made the highest possible savings rate in the 401(k) salient.

Employees assigned to the low cue treatment received the additional sentences, “For example, you could increase your contribution rate by 1% of your income and get more of the match money for which you’re eligible. (1% is just an example, and shouldn’t be interpreted as advice on what the right contribution increase is for you.)” We call this the 1% anchor treatment because it tries to make the cued savings rate sound maximally arbitrary.

Despite our efforts to make the anchor sound arbitrary, recipients may have nonetheless inappropriately inferred something about their optimal savings rate from the anchor. Our objective is not to rule out the possibility that employees performed a Bayesian update about their optimal 401(k) contribution rate based on this cue, but to see if even the most minimal, uninformative cues can have large effects on savings choices. Indeed, mistaken inference is one channel through which cues might operate. Danilowitz, Frederick, and Mochon (2011) find that about 70% of the anchoring effect magnitude identified in the laboratory using standard experimental procedures is due to mistaken inference by subjects.

We could have cued the 60% maximum allowable contribution rate using the same anchoring language, replacing the 1% increase with whatever amount would cause the recipient to contribute 60% of her income to the 401(k). However, we worried that it would sound strange to mention such a large contribution increase as an arbitrary example. Therefore, employees assigned to receive a high cue had the following 60% threshold cue added to their email: “You can contribute up to 60% of your income in any pay period.” Mentioning the extremely high 60% contribution rate was natural in the context of explaining the relevant 401(k) plan rule. In addition to creating an anchor at 60%, making the maximum plan contribution rate salient may activate a rule of thumb tied to the maximum, pushing people to increase their contribution rate. Although information about the 60% maximum was not present in the control email, it is such a high contribution rate that it is not a relevant constraint for most employees, so the marginal information contained in the cue is likely to be small. Since a 60% contribution rate is an implausible recommendation, the 60% threshold cue may also be less likely than the anchoring cue to be interpreted as a recommendation from the employer.

Table 2 shows how the 4,723 email recipients (who represent approximately a quarter of the company’s worldwide employees) in 2009 whom we analyze in this paper were allocated across experimental conditions.11 Employees fell into three categories based on their marginal incentive to increase their before-tax and Roth contribution rate in 2009: those who faced a 100% marginal match on those additional contributions, those who faced a 0% marginal match, and those who faced a 50% marginal match. Eligibility for assignment to experimental conditions depended on the employee’s category. Employees had an equal probability of being assigned to each condition for which they were eligible.

Table 2. Subjects per experimental cell for 2009 emails.

This table shows the number of employees who received each version of the 401(k) email in 2009. The numbers are reported separately by projected contribution category. Projected contributions are the total before-tax plus Roth contributions to the 401(k) an employee would have ended up with in 2009 if the contribution rates effective on November 4, 2009 remained unchanged for the remainder of 2009.

| Projected 2009 before-tax + Roth contributions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| $0 – $2,499 | $2,500 – $4,999 | $5,000 – $16,499 | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Control | 257 | 651 | 973 |

| 1% anchor | 0 | 0 | 968 |

| 60% threshold | 252 | 651 | 971 |

Employees on pace to contribute at least $5,000 if they left their contribution rate unchanged for the rest of the year—and thus faced a 50% marginal match—could be assigned to the control, the 1% anchor treatment, or the 60% threshold treatment.12 The anchor cue’s implication that increasing one’s contribution rate by the anchor amount would increase the match earned was not necessarily true for employees whose marginal match on the next dollar of contribution increase was zero (i.e., employees on pace to contribute $2,500 to $4,999). And the implication could be somewhat misleading for employees whose marginal match on the next dollar of contribution increase was 100% (i.e., employees on pace to contribute less than $2,500), because much of the increase beyond the next dollar could be in the region where the marginal match was 0%. This is why we did not administer the 1% anchor to any employee on pace to contribute less than $5,000. These employees had an equal chance of receiving either the control email or the 60% threshold email.

IV. Analysis of 2009 experiments

A. Control email recipient behavior

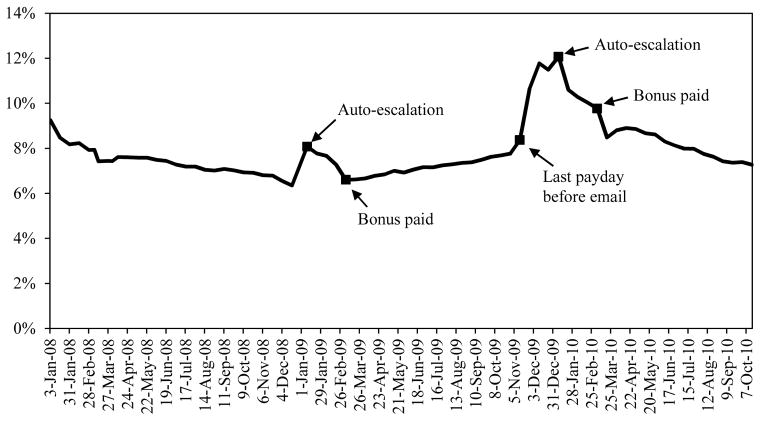

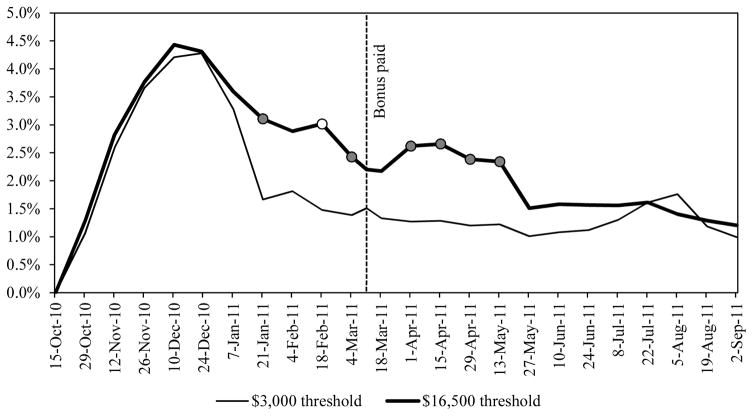

The control email contains its own plethora of information and numerical cues, and also serves as a reminder about saving.13 The cue effects that are the focus of this paper represent impacts above and beyond those of the control email. Figure 2 shows the average total contribution rate—before-tax plus Roth plus after-tax—at each payday for the subset of the 2009 control group (combined across all projected contribution categories) that was employed at the company on January 3, 2008.14 The graph ends on October 15, 2010, the last payday before the 2010 emails were sent.

Figure 2.

Average total contribution rate among November 2009 control email recipients employed at company as of January 3, 2008

The impact of the company’s 1% contribution auto-escalation is visible at the beginning of 2009, but it begins to be reversed immediately. By the beginning of March 2009, when the annual bonus was paid, the average total contribution rate is similar to what it was immediately prior to the auto-escalation—a little over 6%. This strong reversal is surprising in light of the success the auto-escalation program studied by Thaler and Benartzi (2004) had at raising long-run 401(k) contribution rates. The lack of inertia at this company may be due to the bonus serving as a focal deadline for action. The trajectory of contribution rates changes sharply after the 2009 bonus, going from trending downward to trending upward.

The impact of our 2009 control email appears to be large. The average total contribution rate on November 27, 2009—the first payday following the email—of control recipients employed since January 2008 was 10.7%, which is 2.3% of income higher than it was two weeks earlier. The average contribution rate increased further to 11.8% on December 11, 3.4 percentage points higher than it was on November 13. The average then fell slightly to 11.5% on December 24. By comparison, during the last three pay periods of the prior year, the sample’s average total contribution rate fell by 0.5% of income.

Like in the prior year, the average contribution rate of control recipients declined significantly in early 2010 as the bonus payment approached. By the first pay period after the bonus, the average contribution rate of 8.5% was only slightly above what it was in the last pay period before the email (8.4%). Some of the decline in the total contribution rate after the bonus pay period is due to employees hitting the legal calendar-year maximum of $16,500 in before-tax plus Roth contributions, at which point their before-tax and Roth contribution rates are automatically set to zero.

B. Econometric methodology for estimating cue effects

We identify our cue treatment effects by comparing employees in a projected contribution category who received a cue to control email recipients in the same category. In other words, we compare each treatment group in a column of Table 2 to control email recipients within the same column. Random assignment within projected contribution category makes the characteristics of employees who received each cue treatment in a category equal in expectation to those of their corresponding control group, so we can compare outcomes without additional control variables. Untabulated randomization checks show that contribution rates immediately prior to the email, year-to-date dollars contributed to the 401(k) prior to the email, projected 401(k) dollar contributions for the calendar year if the employee kept his pre-email contribution rate unchanged, and salaries do not differ significantly between any treatment × projected contribution category group and its corresponding control group. Any aggregate or company-wide shocks that occur during our observation period would affect both treatment and control groups equally in expectation, and therefore do not threaten the internal validity of our treatment effect estimates.

Our regressions follow an event-study framework. The event date is November 17, 2009, the event is the sending of the cue, and the benchmark is the appropriate set of control email recipients. As is the norm in event studies, we estimate the effect of the event at multiple individual post-event periods by running a separate regression for each post-email payday. Our main dependent variable is the difference in the total 401(k) contribution rate (before-tax plus after-tax plus Roth) between the payday being evaluated and the last payday prior to the email, and our explanatory variable is a treatment dummy.15

We also estimate treatment effects averaged over multiple periods by using as our dependent variable the average total 401(k) contribution rate during the averaging window (equally weighting each pay period) minus the pre-email total 401(k) contribution rate. We restrict the sample to employees who were still at the company at the end of the period we are averaging over. The advantage of this approach relative to the individual payday regressions is that it concisely estimates the longer-run impact of the treatment and can have more power to detect small treatment effects that persist for many periods. The disadvantage is that when a nonzero treatment effect has a duration that is shorter than the averaging period, statistical power to detect the effect diminishes because the cumulative treatment effect size becomes small relative to the cumulative residual variance.16 Our two averaging windows for the 2009 experiments will always be the seven paydays (November 27, 2009 to February 19, 2010) between the 2009 email send date and the 2010 bonus payday, and the sixteen paydays (March 19, 2010 to October 15, 2010) between the 2010 bonus payday and the 2010 email send date. We split the averaging windows at the bonus payday for two reasons. First, the bonus payday is a psychologically and economically significant date that motivates a great deal of 401(k) activity, and we see sharp changes in contribution rate trajectories at the bonus payday prior to our 2009 emails. Second, because we do not know how large each employee’s bonus is, we do not know how to weight the pre-bonus, bonus, and post-bonus contribution rates to construct a cue’s effect on total contributions as a percent of total compensation across all 24 paydays after the email was sent.

C. Effect of the 1% anchor

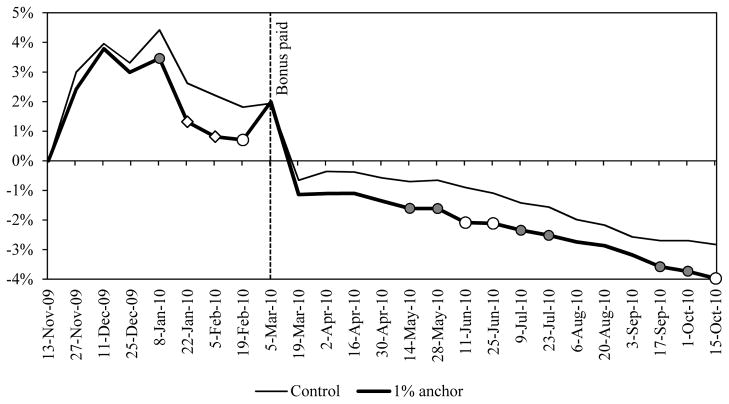

Our first experimental finding is that the low 1% anchor decreased subsequent contribution rates. Figure 3 plots for 1% anchor recipients and their corresponding control group the average total contribution rate each pay period minus the total contribution rate the recipient had in effect on November 13, 2009, the last payday before the 2009 emails. Gray circles, hollow circles, and hollow diamonds show where the 1% anchor group’s difference from its control group in a pay period is significant at the 10%, 5%, or 1% level, respectively. (The online appendix contains tables of regression coefficients that correspond to the statistical tests in this figure and subsequent figures.)

Figure 3. 1% anchor vs. control: Average total contribution rate in excess of November 13, 2009 contribution rate.

Gray circles, hollow circles, and hollow diamonds indicate a difference from the control in that pay period that is significant at the 10%, 5%, or 1% level, respectively.

The average contribution rate of the 1% anchor group and its control group both rose during the first two pay periods before beginning to fall, but the 1% anchor group was persistently below the control group until March 5, 2010, when the two converged as bonuses were paid. Surprisingly—given our prior expectation that anchoring effects would be strongest immediately after the email was sent—the gap between the 1% anchor group and the control group took eleven weeks to reach its peak magnitude of 1.4% on February 5. The treatment effect is not statistically significant before year-end 2009, but from January 22 to February 19, 2010, the 1% anchor decreased average total contribution rates by between 1.1% and 1.4% of income at the 5% significance level during one payday and at the 1% level during the other two. We will see in Section VI.C that when we tested anchor cues in the 2010 emails, we once more observed significant delays in their effects on average contribution rates.

The average contribution rate series diverged from each other after March 5, with the 1% anchor group again consistently contributing less than the control group through October 15 by as much as 1.2% of income. Of the sixteen post-bonus paydays in Figure 3, the 1% anchor effect is significant at the 5% level on June 11 and June 25, and again on October 15—eleven months after the email date. During these three dates, the 1% anchor decreased contribution rates by between 1.0% and 1.2% of income. The 1% anchor effect is also marginally significant at the 10% level on six other post-bonus paydays.

The fact that the 1% anchor had no significant effect on average contribution rates in 2009 does not mean it had no effect at all that year. A linear probability regression (not shown in exhibits) reveals that 1% anchor recipients were 1.5 percentage points more likely (p = 0.035) than the control group to have a contribution rate exactly 1% of income higher than their November 13, 2009 contribution rate during at least one pay period between November 27 and December 24, 2009. This increase represents a doubling of the control group’s baseline probability of 1.6%. On the other hand, there is much less clustering at the cued action than there typically is at a default contribution rate. Choi et al. (2004), for example, find that shortly after the deadline to opt out of 401(k) automatic enrollment has passed, 68% to 86% of newly hired employees are at the contribution rate default.

We can examine the 1% anchor effect integrated over periods of time longer than one payday. Averaged across both individually significant and insignificant paydays, the 1% anchor decreased contribution rates by 0.8% of income (p = 0.047) during the seven pre-bonus paydays between November 27 and February 19, had no effect on the March 5 bonus payday (+0.05% of income, p = 0.933), and decreased contribution rates by 0.8% of income (p = 0.076) during the sixteen post-bonus paydays from March 19 to October 15.

Note that there is no contradiction between the fact that the 1% anchor mentioned a contribution increase and the fact that its treatment effect relative to the control email is negative. Recipients of the 1% anchor did raise their contribution rates on average relative to where they were before the email. They simply did not raise them as much as the control group, in accordance with the low contribution increase that was cued.

The delayed reaction of the average contribution rate to the 1% anchor may be consistent with previous findings that minor psychological interventions can influence behavior after a significant delay. Research on “mere measurement” (e.g., Morwitz, Johnson, and Schmittlein, 1993) and the “self-prophecy effect” (e.g., Spangenberg, 1997) has shown that asking people about their future intentions or asking them to predict their future behavior can change their actual behavior months later. For example, Dholakia and Morwitz (2002) find that asking customers of a financial services firm about their satisfaction with their current firm led to an increased likelihood of opening an additional account and a decreased likelihood of ending their relationship with the firm, and these effects increased in magnitude for 3 to 6 months after the intervention. Alternatively, our delayed effect may be due not to a single cue exposure’s effect growing over time, but to the cumulative impact of multiple exposures that occurred when employees re-read the email weeks after it had been sent in order to remind themselves of the instructions on how to change their contribution rate.17

The treatment effect on the average contribution rate is not delayed because employees who reacted to the email later are more susceptible to anchors. The average contribution rate among employees who changed their contribution rate between the email send date and year-end 2009 also exhibited a growing divergence between the 1% anchor and control groups in January, an attenuation of the anchor effect on the bonus payday, and a re-emergence of the anchor effect after the bonus. The delayed treatment effect was also not caused by fewer anchor recipients being subject to auto-escalation at the beginning of 2010 than control employees. In fact, slightly more anchor recipients (17%) than control employees (16%) increased their contribution rate by exactly 1% at that time.

The 1% anchor effect’s disappearance on the bonus payday might be explained by previous laboratory evidence that even tiny discrepancies between the choice domain and the anchor domain are enough to eliminate the anchoring effect. Chapman and Johnson (1994) find that valuation of a good in dollar units responds to dollar anchors but not life expectancy anchors, and valuation of a good in life expectancy units responds to life expectancy anchors but not dollar anchors. Strack and Mussweiler (1997) report that height anchors affect height estimates much more than width estimates, and width anchors affect width estimates much more than height estimates. Our 1% anchor text referred to contribution rates on non-bonus paydays. The company’s employees think quite differently about bonus versus non-bonus payday contributions, a mindset reflected in the fact that in 2012, the company introduced a new set of 401(k) contribution rate elections that applies only to the bonus.

Although the 1% anchor resulted in lower average contribution rate increases, did it encourage a larger fraction of recipients to make small contribution rate increases? Online Appendix Table 1, Panel B shows regressions of the probability that a recipient’s total contribution rate during a given pay period was different from her November 13, 2009 total contribution rate, regardless of the size of the change. By the bonus payday, over 70% of 1% anchor recipients and their control group had a different contribution rate in effect, but we find little evidence that the 1% anchor affected the probability of action at any point in time. The contrast between these null results on the probability of action and the significant results on average contribution rates indicates that the 1% anchor did not work by changing the action bands within an Ss model (e.g., Grossman and Laroque, 1990; Lynch, 1996; Gabaix and Laibson, 2002; Sims, 2003; Reis, 2006; Carroll et al., 2009; Alvarez, Guiso, and Lippi, 2012). Instead, the anchor changed the target contribution rate of the recipient.

D. Effect of the 60% contribution rate threshold cue

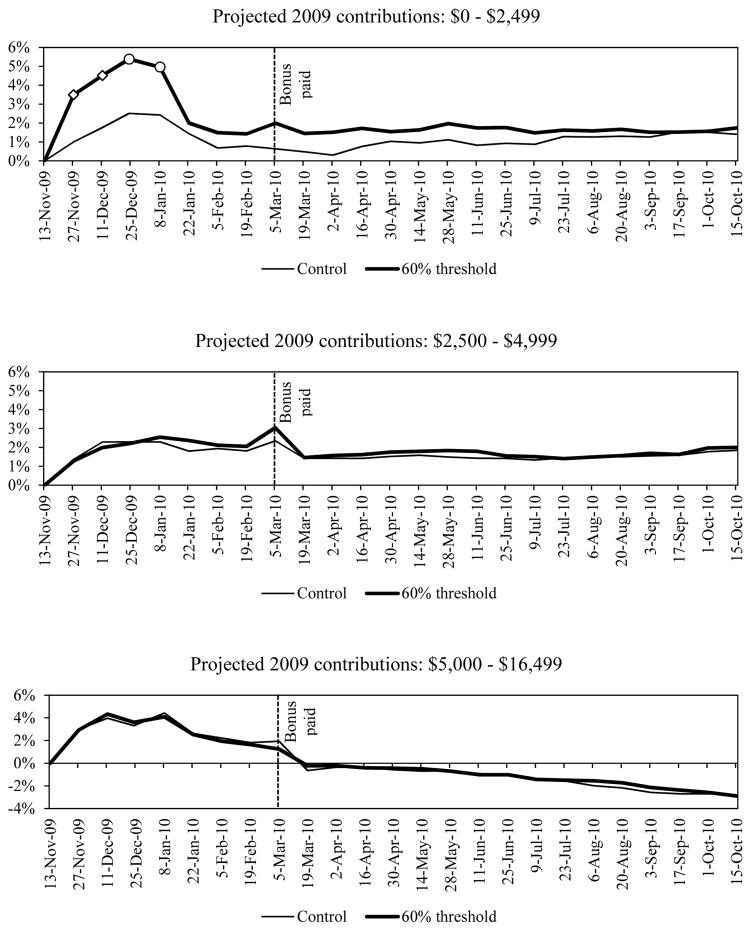

We analyze the effect of the 60% contribution rate threshold cue separately for recipients who were on pace to contribute less than $2,500, between $2,500 and $4,999, and between $5,000 and $16,499 in 2009, since each of these groups faced different marginal matching incentives. We find that this extremely high cue increased subsequent contribution rates, but only among low savers.

Figure 4 plots over time the average total contribution rate in excess of the November 13, 2009 total contribution rate. Recipients of the 60% threshold cue who were projected to contribute less than $2,500 in 2009 immediately raised their contribution rate by 2.5% of income more than their control group, and this gap grew to 2.9% of income on December 24 before attenuating to less than 1% of income from January 22 to October 15. The treatment effects are statistically significant at the 5% level or better through January 8, 2010 and insignificant afterwards. Averaging across paydays, the 60% threshold treatment increased contribution rates by 1.8% of income (p = 0.011) from the email send date to the last pre-bonus payday, and had large but insignificant positive effects on the bonus payday (+1.4%, p = 0.153) and the post-bonus paydays through October 15, 2010 (+0.4%, p = 0.615).

Figure 4. 60% threshold vs. control: Average total contribution rate in excess of November 13, 2009 total contribution rate.

Gray circles, hollow circles, and hollow diamonds indicate a difference from the control in that pay period that is significant at the 10%, 5%, or 1% level, respectively.

Is the 60% threshold treatment effect on low contributors due to their learning from it that the plan’s maximum contribution rate is 60%? According to this explanation, employees in the control group chose smaller contribution increases than they otherwise would have because they falsely believed they were not allowed to contribute more.18 Online Appendix Table 3 presents regression evidence that suggests this explanation is not valid. The dependent variable is a binary indicator for having a higher total contribution rate in a given pay period than one had in effect on November 13, 2009. Among low contributors, those who received the 60% threshold treatment were significantly more likely to make an increase of any size after the email (between 5.7 and 14.7 percentage points in the significant paydays), whereas the information story predicts that both groups would have similar likelihoods of making a contribution increase (albeit of different sizes).

In contrast to what we saw among low contributors, the bottom two graphs in Figure 4 show that the 60% threshold treatment had no effect on average contribution rates among recipients on pace to contribute between $2,500 and $4,999 or between $5,000 and $16,499 in 2009. Because we have many more individuals in the two higher projected contribution categories than in the lowest projected contribution category, the 60% threshold effect is not significant when averaged across the entire sample.

In untabulated regressions, we examine whether the 60% threshold treatment caused recipients to contribute exactly 60% of their income in any pay period between November 27, 2009 and October 15, 2010.19 These regressions show that the 60% threshold treatment made contributing at 60% more likely only for recipients who were previously on pace to contribute less than $2,500 in 2009. The effect for these recipients is a 5.7 percentage point increase (p = 0.020) in the probability of contributing 60%, up from a baseline probability of 5.4% in the control group.

Why did the 60% threshold cue have such heterogeneous effects? Four differences across the three projected contribution categories could be responsible. First, average salaries differ. If low-income individuals are generally more susceptible to “nudges” because of lower financial sophistication, and low-income individuals are more likely to be in the lowest projected contribution category, then the threshold cue would have the strongest effect in the lowest projected contribution category. Second, individuals in the lowest projected contribution category had a low average contribution rate in effect when they received the email, so there was a large gap on average between their status quo and the cued contribution rate. This larger gap may have been more motivating. Third, employees in the lowest projected contribution category had the highest marginal match rate, which may have made them more likely to act upon the motivation created by a cue. Fourth, employees in the lowest projected contribution category may have the lowest dispositional inclination to save, which might give the cue more room to work than in higher-saving employees, who might already have hit the ceiling on their savings motivation.

Any explanation that predicts a monotonic relationship between the treatment effect and salary is easy to rule out. In fact, relative to recipients on pace to contribute less than $2,500, recipients on pace to contribute between $2,500 and $4,999 have an average salary that is 8% lower, while recipients on pace to contribute at least $5,000 have an average salary that is 35% higher.

Evidence in favor of the “large gap” explanation comes from treatment interaction regressions run separately for each projected contribution category. Online Appendix Table 4 shows that within every category, whether or not the 60% cue had a significant overall effect in that category, the treatment effect on average contribution rates is significantly more positive for employees whose November 13 contribution rate was 0% or 1%—and hence furthest from the 60% cue—than for employees with higher November 13 contribution rates.20 For 0% to 1% contributors in the $0 – $2,499 category, the $2,500 – $4,999 category, and the $5,000 – $16,499 category, the 60% cue increased contribution rates in a pay period by as much as 5.2%, 8.9%, or 6.4% of income, respectively. The uninteracted treatment coefficients are never significant, indicating that any non-zero 60% threshold treatment effect resides exclusively among 0 to 1% contributors. Apparently, it is not enough for the gap between the status quo and the threshold cue to be large; it must be extremely large.

Evidence against the marginal match rate and dispositional savings inclination explanations comes from comparing the treatment effect size among 0 to 1% contributors across projected contribution categories. Holding the gap between the status quo and the cue fixed, the 60% threshold treatment effect is more positive in the higher projected contribution categories (as shown in the previous paragraph), where employees have a lower match rate and a higher savings disposition.

In sum, it appears that the 60% threshold cue had a smaller overall treatment effect in the higher projected contribution categories because fewer employees with an extremely large gap between their status quo contribution rate and the cue were in those higher categories. If the number of employees with such a large gap were equally distributed across categories, the higher categories would have responded more positively on average to the 60% threshold cue.

V. Design of 2010 experiments: Dollar threshold cues, higher anchor cues, and goal cues

Our second set of experiments filled three gaps left by the first experiments. First, we had found that cueing a high savings threshold created by the 401(k) plan rules increased contribution rates only if the recipient’s status quo savings behavior was extremely far from the cued threshold. We identified this treatment interaction using variation arising from the distance between one fixed threshold cue and an endogenously chosen status quo. Could we confirm using randomized variation that cueing a more distant savings threshold created by the 401(k) plan rules has a more positive savings effect? Second, a low anchor lowers contribution rates, but do higher anchors raise contribution rates? Third, is there any cue that could raise contribution rates outside the lowest projected contribution category, averaging across all employees in these categories?

The sample for the second round of emails was employees who were on pace to contribute less than $16,500 on a before-tax plus Roth basis in 2010 if they left their contribution elections as of October 15, 2010 unchanged.21 Emails were sent on October 19, 2010. The 2010 email template was identical to the 2009 template, except that the match information was updated to reflect the new match structure, the year-to-date contribution information reflected 2010 contributions, and the statement about increasing one’s contribution rate was replaced by, “To take greater advantage of [Company]’s 2010 match, increase your contribution rate soon before the year is over.” Treatment emails were identical to the control emails except for the addition of a cue at the point indicated in Figure 1.

Table 3 shows how the 3,487 email recipients in 2010 (who represent about one-seventh of the company’s worldwide employees) whom we analyze in this paper were allocated across experimental conditions. Assignment to conditions in 2010 was independent of assignments in 2009. The sample size is smaller than in 2009 because fewer employees in 2010 were not on pace to contribute $16,500 for the year.

Table 3. Subjects per experimental cell for 2010 emails.

This table shows the number of employees who received each version of the 401(k) email in 2010. The numbers are reported separately by projected contribution category. Projected contributions are the total before-tax plus Roth contributions to the 401(k) an employee would have ended up with in 2010 if the contribution rate effective on October 15, 2010 remained unchanged for the remainder of the calendar year.

| Projected 2010 before-tax + Roth contributions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| $0 – $2,999 | $3,000 – $5,999 | $6,000 – $16,499 | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Control | 0 | 263 | 560 |

| $3,000 threshold | 226 | 0 | 0 |

| $16,500 threshold | 225 | 0 | 0 |

| 3% anchor | 0 | 0 | 561 |

| 10% anchor | 0 | 0 | 562 |

| 20% anchor | 0 | 0 | 565 |

| $7,000 savings goal | 0 | 263 | 0 |

| $11,000 savings goal | 0 | 262 | 0 |

We tested the effect of cueing closer versus farther savings thresholds created by the 401(k) plan rules on those who faced a marginal match rate of 100%—employees on pace to contribute less than $3,000 on a before-tax plus Roth basis in 2010. This is a population similar to the one in which the 60% threshold treatment was effective on average in 2009. These employees were equally likely to have one of two thresholds created by the 401(k) match cued. The $3,000 threshold cue was, “The next $x of contributions you make between now and December 31 will be matched at a 100% rate,” where x was the difference between $3,000 and the employee’s year-to-date before-tax plus Roth contributions. The $16,500 threshold cue was, “Contributing $y more between now and December 31 would earn you the maximum possible match,” where y was the difference between $16,500 and the employee’s year-to-date before-tax plus Roth contributions. Both dollar threshold cues contain no information that could not be inferred from the 2010 email template, which described the plan’s matching structure and how many dollars the employee had contributed so far in 2010. Since not many employees were on pace to contribute less than $3,000 in 2010, we did not send the control email to anybody in this projected contribution category.

Like in 2009, we tested anchors on employees who faced a marginal match rate of 50%—those who were on pace to make at least $6,000 in before-tax plus Roth contributions in 2010. This group could be assigned to the control, the 3% anchor, the 10% anchor, or the 20% anchor.22 The 3%, 10%, and 20% anchor cue text was identical to the 1% anchor cue text from 2009, except that the example increase was 3%, 10%, or 20%.

At the time we designed the 2010 experiments, we did not know whether the higher anchors would raise contribution rates. Therefore, to see whether a more potent cue would successfully raise the average higher saver’s contribution rate, we also administered cues with an additional psychological element: goal-setting. We tested goal cues on employees whose marginal match rate was 0%—those on pace to contribute between $3,000 and $5,999 on a before-tax plus Roth basis in 2010. Recall that individuals facing this match rate were on average unresponsive to the 60% threshold cue in 2009.

Employees in this middle projected contribution category were equally likely to receive the control email, the $7,000 savings goal treatment, or the $11,000 savings goal treatment. The $7,000 savings goal treatment consisted of two additional sentences added to the control email: “For example, suppose you set a goal to contribute $7,000 for the year and you attained it. You would earn $500 more in matching money this year than you’re currently on pace for.” We chose $7,000 because it was a modest distance above the $6,000 threshold at which the marginal match rate would turn positive for these employees. The $11,000 savings goal treatment email instead contained the sentences, “For example, suppose you set a goal to contribute $11,000 for the year and you attained it. You would earn $2,500 more in matching money this year than you’re currently on pace for.” The goal cues contain no information that could not be inferred from the control email. Although we could have chosen $16,500 as the high goal, an advantage of using $11,000 instead is that any additional effect of the high cue would not be attributable to the high amount being a more focal number than the low goal cue’s amount.

VI. Analysis of 2010 experiments

A. Econometric methodology

Our econometric methodology for analyzing the 2010 experiments mirrors our methodology for the 2009 experiments: We identify treatment effects by comparing employees within a projected contribution category who were assigned to receive a treatment to control email recipients in the same category. Because we did not send control emails to employees on pace to contribute less than $3,000 in 2010, our dollar threshold treatment analysis will only estimate the $3,000 threshold treatment effect relative to the $16,500 threshold treatment effect. When averaging over multiple pay periods, the two averaging windows we use will always be the ten paydays (October 29 to March 4) between the 2010 email send date and the 2011 bonus payday, and the thirteen paydays between the 2011 bonus payday and the end of our sample period (March 18 to September 2).

Untabulated randomization checks show that contribution rates immediately prior to the email, year-to-date dollars contributed to the 401(k) prior to the email, projected 401(k) dollar contributions for the calendar year if the employee kept his pre-email contribution rate unchanged, and salaries do not differ significantly between any treatment group and its corresponding control group or between the $3,000 and $16,500 threshold treatment groups.

B. Effect of the $3,000 and $16,500 savings threshold cues

Our analysis confirms using randomized variation that cueing a more distant savings threshold created by the 401(k) plan rules generates higher contributions than cueing a closer savings threshold. Figure 5 shows that the average total contribution rates in excess of the October 15, 2010 total contribution rates were quite similar between the $3,000 and $16,500 threshold cue recipients through year-end 2010. But a large gap opened up in 2011, as $3,000 threshold cue recipients dropped their contribution rate much more than $16,500 threshold cue recipients. Seeing the lower threshold appears to have made recipients satisfied with achieving a lower savings level, causing them to contribute less afterwards. The difference between the two groups’ average total contribution rates peaked at 1.5% of income on February 18, when it also achieves statistical significance at the 5% level. The difference is also marginally significant at the 10% level on January 21, March 4, and April 1 through May 13, and completely disappears by July 22. Online Appendix Table 5 indicates that the threshold treatments generated differential effects on average contribution rates without significantly affecting the probability of changing one’s contribution rate from one’s October 15 contribution rate. Because the significant effects on average contribution rates straddle the bonus pay period but do not extend far away from it, the effects averaged over the ten pre-bonus paydays from October 29 to March 4 (+0.7, p = 0.381) or over the thirteen post-bonus paydays from March 18 to September 2 (+0.6%, p = 0.150) are not statistically significant.23 The $16,500 threshold group contributed 0.7% more of its March 11 bonus, but that difference too is not statistically significant (p = 0.359).24

Figure 5. $16,500 threshold vs. $3,000 threshold: Average total contribution rate in excess of October 15, 2010 total contribution rate.

Gray circles, hollow circles, and hollow diamonds indicate a difference from the $3,000 threshold group in that pay period that is significant at the 10%, 5%, or 1% level, respectively.

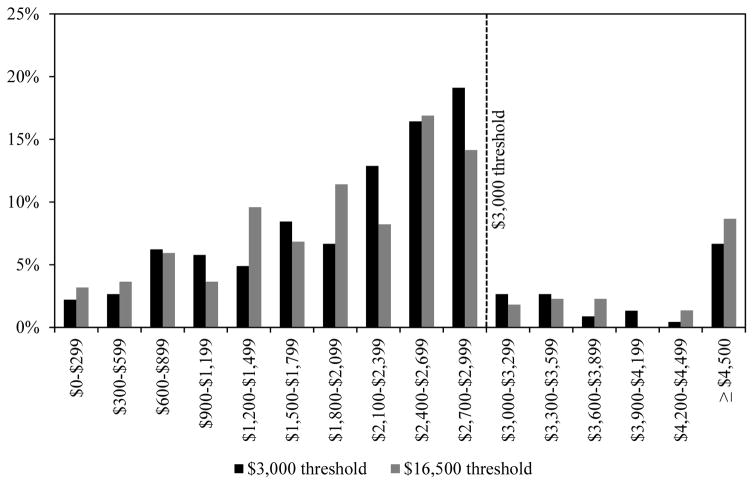

We also examine histograms of total 2010 before-tax plus Roth contribution amounts to see whether the $3,000 threshold cue caused clustering of 2010 contributions around $3,000.25 Figure 6 shows that those who received the $3,000 threshold treatment appear more likely than those who received the $16,500 threshold treatment to end up with 2010 before-tax plus Roth contributions clustered around $3,000. However, we do not have enough power to statistically distinguish from zero the 5.8 percentage point increase in the probability of having 2010 contributions totaling between $2,700 and $3,299 (p = 0.120).

Figure 6.

Histogram of total before-tax plus Roth 2010 contributions, email recipients projected to contribute less than $3,000 in 2010

Although the dollar threshold cues are like the 60% threshold cue in that they are more effective when further away from the recipient’s status quo, the timing of this interaction effect differs. Comparing the 60% threshold treatment interaction analysis in Online Appendix Table 4 to the difference between the two dollar threshold groups in Figure 5, we see that the 60% threshold cue immediately caused recipients far away from the cue to contribute more than those who are closer, whereas the $16,500 dollar threshold cue didn’t increase contributions relative to the $3,000 threshold cue for the first three months. This difference could be due to the fact that the $3,000 threshold cue was quite close to most recipients’ status quo—their average year-to-date contribution prior to the email was only about $1,000 below the $3,000 threshold, and 15% of $3,000 threshold recipients ended up contributing more than $3,000 in 2010—whereas even those who were relatively close to the 60% threshold cue were still quite far away in an absolute sense on average. The goal literature has documented that motivation increases when an individual is close to a goal but diminishes upon attainment (Förster, Liberman, and Friedman, 2007; Pope and Simonsohn, 2011; Allen et al., 2013). If savings thresholds operate in a similar fashion, then cueing the close $3,000 threshold may have increased contributions in the short run—thus eliminating any average contribution rate gap with respect to the $16,500 threshold group while causing the spike in 2010 contributions around $3,000—and decreased them in the medium run, creating the pattern in Figure 5. But we cannot directly test this hypothesis because we did not send a control email to any employees in the lowest contribution category in 2010.

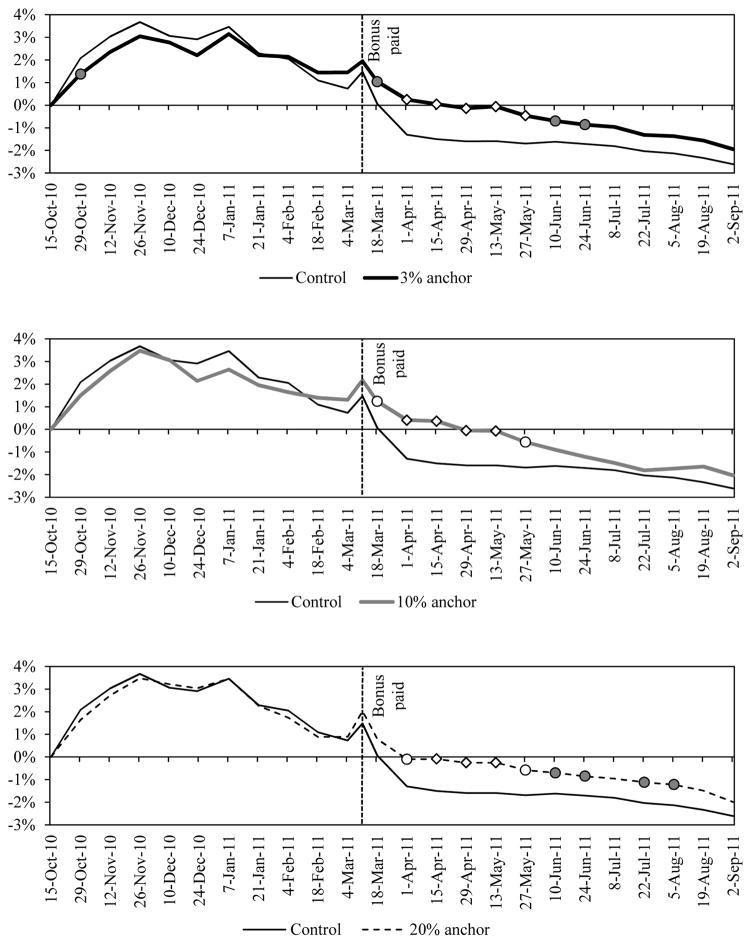

C. Effect of the 3%, 10%, and 20% anchors

We find that higher anchors increased average contribution rates, but as with the 1% anchor, the effect on average contribution rates emerged only with a substantial delay. Figure 7 shows the average total contribution rates in excess of the October 15, 2010 contribution rates of anchor recipients and their corresponding control group. Up through the March 11 bonus, there is no effect on average contribution rates that is significant at the 5% level, and we cannot reject the equality of all the anchor treatment effects in every pay period before the bonus. Averaging across the ten pre-bonus paydays between October 29 and March 4, the 3%, 10%, and 20% anchor groups had contribution rates that were lower than the control group’s by 0.2% of income (p = 0.451), 0.2% of income (p = 0.458), and 0.1% of income (p = 0.836), respectively. The anchors also had no significant effects on bonus contribution rates.

Figure 7. 3%, 10%, and 20% anchors vs. control: Average total contribution rate in excess of October 15, 2010 total contribution rate.

Gray circles, hollow circles, and hollow diamonds indicate a difference from the control in that pay period that is significant at the 10%, 5%, or 1% level, respectively.

But after the bonus, all three higher anchors became highly effective at raising contribution rates. The effects are statistically significant at the 5% level—and often at the 1% level—from March 18 to May 27, and their magnitudes are large: up to 1.5% of income for the 3% anchor, 1.9% of income for the 10% anchor, and 1.4% of income for the 20% anchor. However, we again cannot reject the three effects’ equality in any pay period. Averaging across the thirteen post-bonus paydays from March 18 to September 2, the 3%, 10%, and 20% anchors increased contribution rates by 1.1% (p = 0.028), 1.1% (p = 0.031), and 1.0% (p = 0.019) of income, respectively.

The fact that the anchoring effect does not increase as the anchor rises above 3% is perhaps surprising. But it is consistent with the laboratory evidence of Quattrone et al. (1981) and Chapman and Johnson (1994), who find that extremely high anchors have effects that are similar to moderately high anchors. This pattern of effects that quickly level off with distance contrasts with the threshold cue effects, which are strongest at great distance, suggesting that our anchoring effects are psychologically distinct from our threshold cue effects.

The higher anchors do have some effects on outcomes other than the average contribution rate that differ from the corresponding effects of the 1% anchor. Unlike the 1% anchor, they caused some recipients to disengage from their 401(k) in the short run. Online Appendix Table 6, Panel B shows that the higher anchors decreased the probability of having a contribution rate that differs from one’s October 15 contribution rate in a given pay period by as much as 8 percentage points before the bonus, perhaps because the mention of arbitrary high savings increases with no accompanying justification or context discouraged some recipients who could not afford such an increase. The statistical significance of this effect seems stronger for higher anchors, but we cannot reject equality across anchors. The disengagement effect disappears after the bonus, perhaps because the accompanying increased financial slack allowed recipients to overcome their discouragement. In untabulated regressions, we also find that none of the anchors increased the probability that the recipient’s contribution rate was exactly 3%, 10%, or 20% higher than her October 15, 2010 contribution rate in a subsequent pay period before year-end 2010.

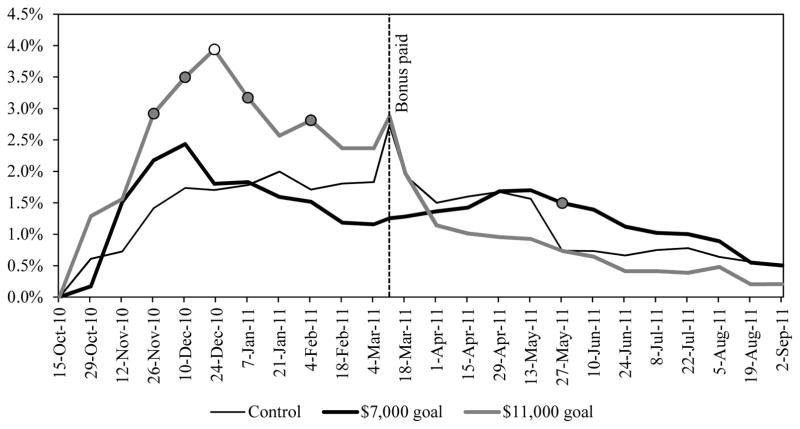

D. Effect of the $7,000 and $11,000 savings goal cues

Employees facing a 0% marginal match rate did not respond significantly on average to the 60% threshold cue in 2009, but cueing a very high arbitrary savings threshold using goal-setting language did raise average contribution rates among this group in 2010. Figure 8 shows that through March 4, 2011, the $11,000 goal group had persistently higher average contribution rates than the control group, with the gap peaking at 2.2% of income and achieving significance at the 5% level at year-end 2010 before disappearing from April 1 onward. Averaging across paydays, the $11,000 goal increased contribution rates by 1.1% of income (p = 0.043) from the email send date to the last pre-bonus payday, had no effect on the bonus contribution (+0.1%, p = 0.893), and had no average effect from the first post-bonus payday to September 2 (−0.2%, p = 0.621).

Figure 8. Goals vs. control: Average total contribution rate in excess of October 15, 2010 total contribution rate.

Gray circles, hollow circles, and hollow diamonds indicate a difference from the control in that pay period that is significant at the 10%, 5%, or 1% level, respectively.

On the other hand, the $7,000 goal treatment effect is never significant at the 5% level on any individual payday. Nor does it have a significant effect averaged over paydays before the bonus (+0.02%, p = 0.971), on the bonus contribution (−1.5%, p = 0.145), or averaged over paydays after the bonus (+0.3%, p = 0.358). The $7,000 savings threshold was a fairly high cue, since it was quite a bit above its recipients’ year-to-date contributions prior to the email—$3,157 higher on average—and only 5% of recipients ended up contributing at least $7,000 in 2010. Thus, our finding is that a moderately high goal cue had no effect, whereas an extremely high goal cue did have a positive effect. This result is similar to our finding that the 60% threshold cue raised contribution rates only among recipients extremely far from the cue. However, the $11,000 goal cue was considerably more effective among moderate savers than the 60% threshold cue.

Heath, Larrick, and Wu (1999) argue that goals very far from the status quo create a “starting problem,” where individuals find it difficult to get themselves to start a task. But Online Appendix Table 7, Panel B shows no evidence that the extremely ambitious $11,000 goal generated a starting problem. The probability of having a contribution rate different than one’s October 15, 2010 contribution rate was between 1.5 and 5.9 percentage points higher among $11,000 goal recipients than control email recipients, depending on the pay period, although this difference is never significant at the 5% level. Nor was there ever a significant difference in the probability of action between the $7,000 and $11,000 goal groups. Therefore, unlike high anchors, high goal cues raised contribution rates without decreasing engagement with the 401(k), perhaps because of the salutary motivational effects of ambitious goal-setting.

VII. Multiple hypothesis testing concerns

Savings choices move towards savings cues, but this effect often emerges only after a delay. In addition, cueing high savings thresholds—with or without goal language—raises contribution rates only if the threshold is very far from the recipient’s status quo. The fact that we find null effects in some time periods and circumstances may cause concern that our statistically significant cue effects are all Type I errors arising from testing hypotheses on multiple cues over multiple time periods. If this is the case, then we should not be able to reject the hypothesis that all of the cue effects on our main outcome variable—average contribution rate in excess of the pre-email contribution rate—are jointly zero.

For each cue, we include three contribution rate effects in our test: its average effect before the first bonus following the cue, its effect on the bonus period contribution, and its average effect after the bonus. For the 2009 cues, the post-bonus period ends on October 15, 2010; for the 2010 cues, the post-bonus period ends on September 2, 2011. Because we analyzed the 60% threshold cue effects separately by projected contribution category, we include a separate triplet of pre-bonus, bonus, and post-bonus 60% threshold cue effects for each category, so that nine 60% threshold treatment effects are included. For the dollar threshold cues, we include only the effects of the $16,500 threshold cue relative to the $3,000 threshold cue, since there is no control email group that is an appropriate benchmark for these employees. The joint test encompasses 30 treatment effect estimates. We describe the details of the test’s implementation in the online appendix.

A Wald test with standard errors clustered by employee rejects with a p-value of 0.021 the hypothesis that the treatment effects are jointly equal to zero.

VIII. Conclusion

This paper documents that minimal numerical cues can influence decisions as economically significant and familiar as retirement savings plan contributions. Low cues decreased contribution rates by up to 1.4% of income in a pay period, and high cues increased contribution rates by up to 2.9% of income in a pay period. Minimal anchoring cues have the most enduring effect—up to a year after the initial email is sent—but take several months to begin affecting average contribution rates. In addition, high anchors reduce the probability of changing one’s 401(k) contribution rate in the short run, and extremely high anchors raise contribution rates by no more than moderately high anchors. Cueing a threshold created by 401(k) plan rules can have more immediate effects and does not reduce the probability of action, but at the cost of a less enduring effect that is confined to those very far away from (and possibly also those very close to) the cued threshold. Goal language added to an arbitrary savings threshold cue appears to be more potent than a threshold cue alone.

The potency of cues presents an opportunity for organizations and policymakers to influence savings outcomes at lower cost than providing financial education or increasing the return to saving. Cues have the advantage of being less heavy-handed than other choice architecture interventions currently in wide use, such as changing the default or narrowing choice menus. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that cues become less effective with repeated exposure, in untabulated results, we find no systematic evidence that treatment effects are weaker among 2010 email recipients who had also received 2009 emails than among those who had not. One piece of evidence of the attractiveness of cues is the fact that, based on the findings of our study, the company at which we ran our experiments has incorporated savings cues into its ongoing 401(k) communications to employees.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kalok Chan, Eric Johnson, David Hirshleifer, Christoph Merkle, Alessandro Previtero, Shanthi Ramnath, Joeri Sol, Victor Stango, and audiences at Columbia, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, George Washington University, Harvard, HKUST Household Finance Symposium, IZA/WZB Field Days conference, University of Mannheim, Miami Behavioral Finance Conference, Michigan State University, NBER Household Finance Meeting, NBER Aging Summer Institute, Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, Queen’s University Behavioral Finance Conference, UCSB/UCLA Conference on Field Experiments, UCLA, University of Melbourne, and Yale for helpful comments, and Google and the National Institute on Aging (grant R01-AG-021650) for financial support. We are grateful for Minhua Wan’s comments and assistance with database management. Part of the work on this paper was done while Emily Haisley was a post-doctoral associate at Yale and Jennifer Kurkoski was a doctoral student at UC Berkeley.

Footnotes

JEL codes: D03, D14, D91, G02

Of course, an anchor may also be subsequently adopted as a goal, or may coincide with a certain savings threshold created by the plan’s rules.

See Benartzi et al. (2017) for other comparisons of impact to cost ratios of nudges versus traditional financial inducements.

See Samuelson and Zeckhauser (1988), Madrian and Shea (2001), Choi et al. (2002, 2004), Thaler and Benartzi (2004), Beshears et al. (2008), and Benartzi, Peleg, and Thaler (2012).

There is evidence that procrastination, cognitive costs of action, and forgetfulness contribute to inertia (Huberman, Iyengar, and Jiang, 2004; Carroll et al., 2009; Choi, Laibson, and Madrian, 2009; Iyengar and Kamenica, 2010; Beshears et al., 2013; Karlan et al., 2014). Employees may also interpret the default as conveying implicit advice (Madrian and Shea, 2001; Beshears et al., 2008), although there is little direct empirical evidence for this in 401(k) contribution rates. Bernheim, Fradkin, and Popov (2014) argue that the data are more consistent with anchoring driving default effects.

Those covered by the mandatory defined contribution plan have 15.5% of their income contributed to the plan. Seventy-six percent of recipients were not enrolled in the supplemental plan before the mailing. If these recipients wanted to start contributing, they had to mail in a request for an enrollment kit, at which point they would receive the enrollment forms in a few weeks. They would then have to complete these enrollment forms and physically mail them back. Recipients who were already enrolled in the plan had to physically mail in a form to change their contribution rate.

There are also related papers on communications affecting debt choices in developing countries. See Bertrand et al. (2010) and Cadena and Schoar (2011).

Both principal and capital gains of before-tax contributions are taxed upon withdrawal. Only capital gains of after-tax contributions are taxed upon withdrawal. Roth contributions are made using after-tax dollars, but both principal and capital gains are not taxed upon withdrawal.

hese matching contributions are substantially more generous than the typical 401(k) match.

Because the changes file does not record the contribution rate elections employees had in effect when they first joined the 401(k), we cannot construct a complete contribution rate history between January 3, 2008 and November 3, 2009 for email recipients who were hired after January 3, 2008.

We excluded employees hired in 2009 because we did not know how much they had contributed in 2009 to a 401(k) at a previous employer, so we could not be sure how much they were eligible to contribute to their current employer’s 401(k) in 2009.

Early drafts of this paper also reported results from a 10% anchor treatment administered in 2009. Like the 10% anchor treatment in 2010, the 2009 recipients of the 10% anchor had average contribution rates similar to the control group prior to the bonus and higher average contribution rates afterwards. We exclude the 2009 10% anchor treatment from the current paper because we discovered that by chance, randomization had created a significant difference in the average pre-email contribution rate of the 2009 10% anchor recipients relative to the control group.

We do not analyze employees in this projected contribution category who were not eligible for all three conditions (and they do not appear in Table 2). Employees were eligible for all three conditions if increasing their before-tax plus Roth contribution rate by 1% of income for the remainder of 2009 would not cause their 2009 before-tax plus Roth contributions to exceed $16,500.

See Cadena and Schoar (2011) and Karlan et al. (2014) for other studies on how reminders affect financial behaviors.

Employees who left the company are not included in the averages after their departure date.

Using a first-differenced contribution rate as the dependent variable makes our cross-sectional regression equivalent to a two-period panel regression where the dependent variable is the total contribution rate and the explanatory variables are individual fixed effects, a dummy for whether the observation comes after the email date, and a treatment dummy interacted with the post-email dummy. A difference in differences regression specification, which replaces the vector of individual fixed effects with a constant and a treatment dummy, gives an identical treatment effect point estimate but has a larger standard error because it discards information from the data’s panel structure.

Cochrane (1999) gives the following example of the former case: “[Y]ou can predict that the temperature in Chicago will rise about one-third of a degree per day in spring. This forecast explains very little of the day to day variation in temperature, but tracks almost all of the rise in temperature from January to July.” An example of the latter case is the presence today of storm clouds 100 miles to the west, which explains much of the precipitation during the next 24 hours but little of the cumulative precipitation over the next six months.

Unfortunately, we do not have data on when emails were read.

More explicitly, this explanation assumes that the distribution of latent desired contribution rates x* after the emails is identical across treatment and control groups. However, the control group believes that the maximum possible contribution rate is y < 60%, whereas the treatment group knows that the maximum contribution rate is 60%. Each member i of the control group chooses a contribution rate , while each member of the treatment group chooses . Then the average control group contribution rate is less than the average treatment group contribution rate, but unless a significant mass of people believes that they were already contributing the maximum (which would be contradicted by the emails’ exhortation to “increase your contribution rate”), the probability of increasing one’s contribution rate would be equal across both groups.

The results are qualitatively similar if we only consider the period from November 27, 2009 to December 24, 2009.

We pool together the 0 to 1% contributors because in untabulated regressions where we estimate separate treatment interactions with each November 13 contribution rate from 0% to 5%, the 0% and 1% interactions are large and the other interactions are small or negative.

As we did for the 2009 emails, we excluded employees who were hired in 2010. A sizable number of employees in the 2010 experiments were also sent emails in 2009. However, the number of employees in each 2009 treatment × 2010 treatment cell is relatively small, making us unable to test year-over-year treatment interactions.

We do not analyze employees in this category who were not eligible to be assigned to all four of these conditions—those whose before-tax plus Roth contributions in 2010 would exceed $16,500 if they increased their before-tax plus Roth contribution rate by 20% of income for just one 2010 pay period after the email.

Averaging across the January 7 through July 8 non-bonus paydays, the $16,500 threshold group on average contributed 1.0% of income (p = 0.045) more than the $3,000 threshold group.

Because we do not have information on each employee’s bonus size, if an employee chose to contribute a certain dollar amount out of his bonus (rather than a percentage), we cannot translate that choice into a percentage election. We therefore do not include employees who chose a dollar amount for their bonus contribution in any of our analyses of the 2011 bonus. Only 4.5% of 2010 email recipients chose a dollar amount for their bonus contribution, so the sample loss is small.

We examine before-tax plus Roth contributions instead of total contributions in the histogram because the thresholds in the treatments were linked to the match, which was only earned on before-tax and Roth contributions.

Contributor Information

James J. Choi, Yale University and NBER.

Emily Haisley, BlackRock.

Jennifer Kurkoski, Google Inc.

Cade Massey, University of Pennsylvania.