Abstract

This document represents the first position statement produced by the British Society of Gastroenterology and Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland, setting out the minimum expected standards in diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The need for this statement has arisen from the recognition that while technical competence can be rapidly acquired, in practice the performance of a high-quality examination is variable, with an unacceptably high rate of failure to diagnose cancer at endoscopy. The importance of detecting early neoplasia has taken on greater significance in this era of minimally invasive, organ-preserving endoscopic therapy. In this position statement we describe 38 recommendations to improve diagnostic endoscopy quality. Our goal is to emphasise practices that encourage mucosal inspection and lesion recognition, with the aim of optimising the early diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal disease and improving patient outcomes.

Keywords: OGD, quality, early upper gastro-intestinal cancer, key performance indicators

Introduction

Oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (OGD) is the gold standard test for the investigation of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) symptoms, allowing direct mucosal visualisation, tissue acquisition and when required, therapeutic intervention. Demand has been consistently increasing, with an estimated 3000 OGDs performed per 250 000 population annually.1 This figure is likely to increase further following the introduction of UGI cancer awareness campaigns.2 Certification of training and assessment of competence in the performance of OGD is the remit of the Joint Advisory Group (JAG) on gastrointestinal endoscopy.3 The main focus of this process is on technical competence and procedural safety, with the ability to complete the examination without complications being the primary objective. A combination of a known average rate of failure to diagnose cancer at endoscopy of 11.6%, coupled with a paradigm shift towards detecting early cancers which may be potentially amenable to organ-preserving endoscopic therapy, has necessitated an improvement in quality.4–7 Following the institution of auditable measures, colonoscopy has experienced a significant improvement in quality. It is hoped that a similar implementation of standards can replicate this phenomenon in UGI endoscopy.

Aims and scope

The purpose of this position statement is to reduce variation in practice and standards between individual endoscopists and units by establishing a set of auditable key performance indicators (KPIs). In particular, these recommendations aim to optimise the diagnosis of early neoplasia and premalignant conditions, in order to affect the natural history of UGI malignancies, which are currently associated with a poor prognosis due to late detection. These KPIs are aimed at all UGI endoscopists, who irrespective of background discipline should possess sufficient skill to perform a high-quality diagnostic OGD before independent practice. These KPIs have been written with standard OGD in mind, although it is recognised that alternative modalities are being explored, some of which are being used in parallel—for example, ultrathin transnasal video endoscopy. Where new technology is employed, quality should be maintained, even though technical capabilities may be different. Specific issues related to training, management of specific disease processes and unit management are beyond the scope of this position statement and have therefore not been discussed here.

Most of these recommendations have been designed to be measurable parameters, so that practice can be measured against them. It is expected that where there is a shortfall in meeting accepted targets, measures to improve quality should be instituted. This position statement was developed to provide guidance for endoscopists practising within the UK but, as with recent European guidelines, it is of international relevance.8

Methodology

This position statement was commissioned by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) in association with the Association of UGI Surgeons of Great Britain (AUGIS) and was designed and written by a Guideline Development Group. This group was formed of 10 voting individuals, with representation across the relevant disciplines, including a surgical and a nursing representative. A UGI pathologist specifically reviewed recommendations for tissue acquisition and interpretation.

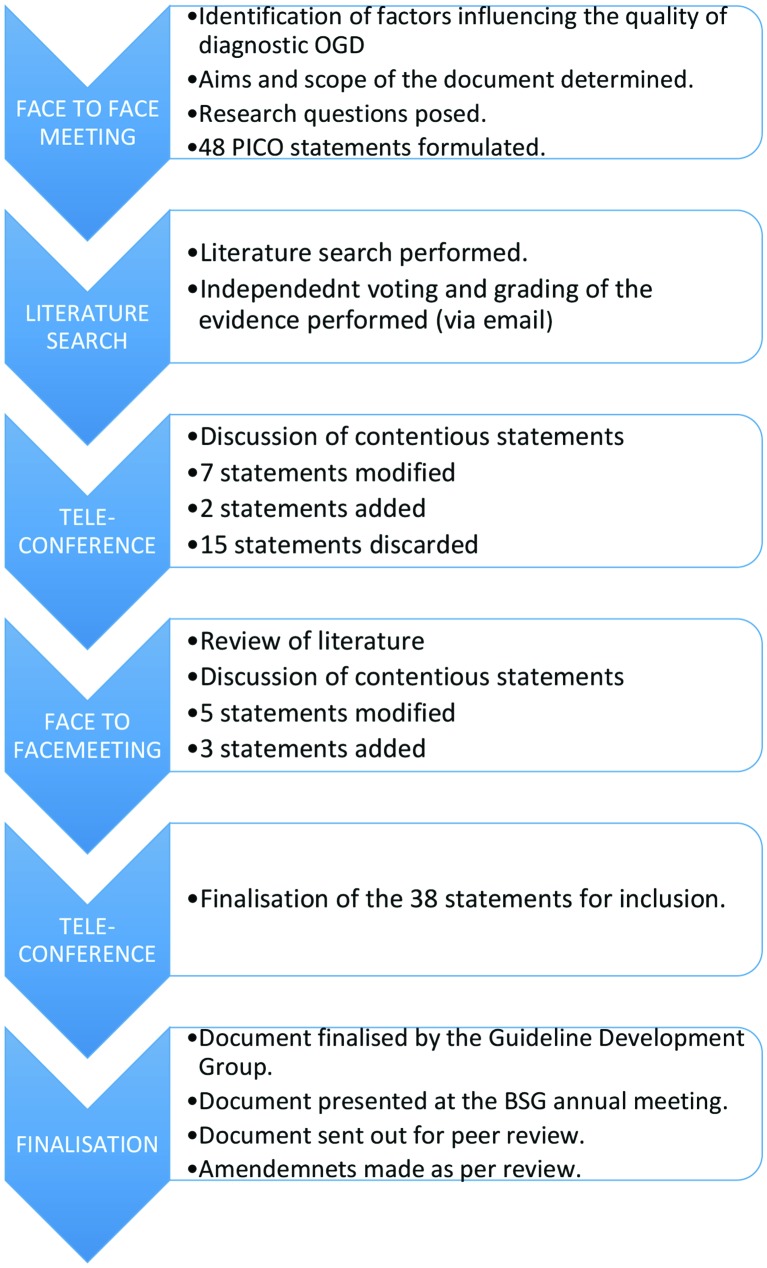

Although this document is a position statement rather than a guideline, we aimed to adopt a similar level of methodological rigour and transparency as described by the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II).9 On meeting, the Guideline Development Group identified factors that were deemed to be important in ensuring a high-quality UGI examination. Research questions were formulated using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) framework, in order to guide a comprehensive search strategy.10 A computerised literature search was performed using PubMed Medline, Embase and the Cochrane Library to identify original research papers, conference abstracts and existing guidelines, through to January 2016. Searches were limited to articles published in English. Review of the bibliographies of the identified clinical studies was used to identify further relevant studies. The resultant body of evidence was reviewed and evaluated by all the members of the group, using the Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) tool.9 Where there was insufficient clinical evidence to support a statement, recommendations were reached by expert consensus. Each member of the group voted on each statement, giving a level of agreement with each KPI using a five-point scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree), with ≥80% agreement required for inclusion. Review of the evidence and initial voting was performed individually. Where consensus was not reached, statements were reviewed, modified and re-evaluated using the Delphi process, until there was sufficient agreement to either include or discard the statement.11 This process occurred via a combination of email, teleconference and face-to-face meetings over a 12-month period (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the statement development process. OGD, oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy; PICO, Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome.

The result of this process was a series of recommendations, with a corresponding level of expert agreement and grading of the relevant evidence (table 1). From these statements a smaller number of KPIs were selected following group discussion. These were chosen based on the potential to influence patient outcomes as well as being both pragmatic and auditable. It is recognised that owing to the nature of some of the areas covered, there may be limited or weak evidence to support specific statements. Where a strong recommendation has been made despite weak evidence, this has been arrived at by expert consensus based on a pragmatic approach. These statements underwent peer review by the BSG Endoscopy Committee, AUGIS and the BSG Clinical Services and Standards Committee. In the majority we have indicated the acceptable target for achieving the measurable parameter, which should be subject to internal audit (table 2). A subset of these recommendations are by their nature either more difficult to measure or have been designed with current developments in endoscopy in mind, and therefore could be considered to be aspirational. Where evaluation of the literature has identified a paucity of evidence in areas pertinent to diagnostic OGD, we have proposed research questions, the answers to which may alter practice in the future. We have divided recommendations logically with respect to the patient pathway into:

Preprocedure

Procedure

Disease specific

Postprocedure.

Table 1.

A summary of the upper gastrointestinal endoscopy quality standards and associated strength of recommendation

| Summary of quality standards | Grade of evidence | Strength of recommendation | Agreement |

| Patients should be assessed for fitness to undergo a diagnostic OGD | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| Patients should receive appropriate information about the procedure before undergoing an OGD | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| An appropriate time slot should be allocated dependent on procedure indications and patient characteristics | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| Informed consent should be obtained before performing an OGD | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| A safety checklist should be completed before starting an OGD | Moderate | Strong | 100% |

| A checklist should be undertaken after completing an OGD, before the patient leaves the room | Weak | Strong | 90% |

| Only an endoscopist with appropriate training and the relevant competencies should independently perform OGD | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| We suggest that endoscopists should aim to perform a minimum of 100 OGDs a year, to maintain a high-quality examination standard | Weak | Weak | 100% |

| UGI endoscopy should be performed with high-definition video endoscopy systems, with the ability to capture images and take biopsies | Weak | Strong | 90% |

| Intravenous sedation and local anaesthetic throat spray can be used in conjunction if required. Caution should be exercised in those at risk of aspiration | Moderate | Strong | 100% |

| A complete OGD should assess all relevant anatomical landmarks and high-risk stations | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| Photo-documentation should be made of relevant anatomical landmarks and any detected lesions | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| The quality of mucosal visualisation should be reported. | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| Adequate mucosal visualisation should be achieved by a combination of adequate air insufflation, aspiration and the use of mucosal cleansing techniques | Moderate | Strong | 100% |

| It is suggested that the inspection time during a diagnostic OGD should be recorded for surveillance procedures, such as Barrett’s oesophagus and gastric atrophy/intestinal metaplasia surveillance | Weak | Weak | 90% |

| Where a lesion is identified, this should be described using the Paris classification and targeted biopsies taken | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| Endoscopy units should adhere to safe sedation practice | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| The length of a Barrett’s segment should be classified according to the Prague classification | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| Where a lesion is identified within a Barrett’s segment, this should be described using the Paris classification and targeted biopsies taken | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| When no lesions are detected within a Barrett’s segment, biopsies should be taken in accordance with the Seattle protocol | Moderate | Strong | 90% |

| If squamous neoplasia is suspected, full assessment with enhanced imaging and/or Lugol’s chromo-endoscopy is required | Moderate | Strong | 100% |

| Oesophageal ulcers and oesophagitis that is grade D or atypical in appearance, should be biopsied, with further evaluation in 6 weeks after PPI therapy | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| The presence of an inlet patch should be photo-documented | Weak | Weak | 90% |

| The presence of a hiatus hernia should be documented and measured | Weak | Weak | 100% |

| Biopsies from two different regions in the oesophagus should be taken to rule out eosinophilic oesophagitis in those presenting with dysphagia/food bolus obstruction, where an alternate cause is not found | Moderate | Strong | 100% |

| Varices should be described according to a standardised classification | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| Strictures should be biopsied to exclude malignancy before dilatation | Weak | Weak | 90% |

| Gastric ulcers should be biopsied and re-evaluated after appropriate treatment, including H. pylori eradication where indicated, within 6–8 weeks | Weak | strong | 90% |

| Where there are endoscopic features of gastric atrophy or IM separate biopsies from the gastric antrum and body should be taken | Weak | Weak | 100% |

| Where iron deficiency anaemia is being investigated, separate biopsies from the gastric antrum and body should be taken, as well as duodenal specimens if coeliac serology is positive or has not been previously measured | Weak | Weak | 80% |

| Where gastric or duodenal ulcers are identified, H. pylori should be tested and eradicated if positive | Moderate | Strong | 100% |

| The presence of gastric polyps should be recorded, with the number, size, location and morphology described, and representative biopsies taken | Moderate | Strong | 100% |

| Where coeliac disease is suspected, a minimum of four biopsies should be taken, including representative specimens from the second part of the duodenum and at least one from the duodenal bulb | Strong | Strong | 100% |

| A malignant looking lesion should be described, photo documented and a minimum of six biopsies taken | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| After OGD readmission, mortality and complications should be audited | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| A report summarising the endoscopy findings and recommendations should be produced and the key information provided to the patient before discharge | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| A method for ensuring histological results are processed must be in place | Weak | Strong | 100% |

| Endoscopy units should audit rates of failing to diagnose cancer at endoscopy up to 3 years before an oesophago-gastric cancer is diagnosed | Weak | Strong | 100% |

IM, intestinal metaplasia; OGD, oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Table 2.

The minimal expected achievement of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy key performance indicators

| Quality indicator | Minimal standard | Aspirational standard |

| A minimum number of 100 OGDs per year should be performed to maintain competence | Not applicable | 100% |

| Photo documentation should be made of relevant anatomical landmarks | Not applicable | >90% |

| Photo documentation should be made of any detected lesions | >90% | 100% |

| Adequate mucosal visualisation should be achieved by a combination of both aspiration and the use of mucosal cleansing techniques | 75% | 100% |

| The quality of mucosal visualisation should be reported | Not Applicable | 90% |

| It is suggested that the inspection time during a diagnostic OGD should be recorded for surveillance procedures, such as Barrett’s and gastric atrophy/intestinal metaplasia surveillance | Not applicable | >90% |

| Where a lesion is identified, this should be described using the Paris classification and targeted biopsies taken | >90% | 100% |

| The length of a Barrett’s segment should be classified according to the Prague classification | >90% | 100% |

| When no lesions are detected within a Barrett’s segment biopsies should be taken in accordance with the Seattle protocol | >90% | 100% |

| Biopsies from two different regions in the oesophagus should be taken to rule out eosinophilic oesophagitis in those presenting with dysphagia/food bolus obstruction, where an alternative cause is not found | >90% | 100% |

| Oesophageal ulcers and oesophagitis that is grade D or atypical in appearance, should be biopsied, with further evaluation in 4–6 weeks of PPI therapy | >90% | 100% |

| Gastric ulcers should be biopsied and re-evaluated after appropriate treatment, including H. pylori eradication where indicated, within 6–8 weeks | >90% | 100% |

| The presence of gastric polyps should be recorded, with the number, size, location and morphology described, with representative biopsies taken | >90% | 100% |

| Where there are endoscopic features of gastric atrophy or intestinal metaplasia separate biopsies from the antrum and body should be taken | Not applicable | >90% |

| Where iron deficiency anaemia is being investigated, separate biopsies from the gastric antrum and body should be taken as well as duodenal specimens if coeliac serology is positive or has not been previously measured | Not applicable | >90% |

| Where gastric or duodenal ulcers are identified, H. pylori should be tested and eradicated if positive | >90% | 100% |

| Where coeliac disease is suspected, a minimum of four biopsies from the second part of the duodenum including a specimen from the duodenal bulb should be taken | >90% | 100% |

| Endoscopy units should audit rates of failing to diagnose upper gastrointestinal cancer at OGD | <10% | <5% |

OGD, oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Preprocedure quality standards

Patients should be assessed for fitness to undergo a diagnostic OGD.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

An assessment of pre-existing conditions and medications should be made before performing an OGD. This can be integrated into the booking-in process or within a preprocedure checklist to avoid duplication. Where changes to antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy are indicated in accordance with existing guidelines, the management strategy should be both documented and communicated to the patient.12

Patients should receive appropriate information about the procedure, before undergoing an OGD.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

In order to be able to give informed consent, information about the proposed procedure and its associated risks must be explained.13 14 As the majority of OGDs are performed on an elective basis, information should be provided before the procedure date, with an opportunity to ask questions.14 There is evidence that information can improve patient experience.15–19 Combined written and oral information appears to be better understood than oral information alone, with little evidence for the use of videotaped information.20–22 Evidence suggests that patients prefer more information rather than less.23 However, it is noted that anxiety correlates with age and gender and may influence the way in which information is delivered.22 There is little to suggest who is best suited to delivering patient information, but in most cases it would be expected to be the referrer proposing or arranging investigations.

An appropriate time slot should be allocated dependent on procedure indications and patient characteristics.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

It is recognised that the time taken to perform an OGD varies depending on indication, pathology and patient factors. Certain clinical indications—for example, the surveillance of premalignant conditions, require careful inspection and possibly the use of advanced imaging and are therefore expected to take longer.24

In Barrett’s surveillance there is some evidence that a ‘Barrett’s inspection time’ of >1 min/cm is associated with a significantly greater detection of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma.25 We would recommend that a standard diagnostic endoscopy is allocated a slot of a minimum of 20 min, increasing as appropriate for surveillance or high-risk conditions.

Informed consent should be obtained before performing an OGD.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

Obtaining informed consent from those with mental capacity is a legal requirement, as outlined in the General Medical Council’s document ‘Consent guidance: legal framework’ and BSG’s ‘Guidance for obtaining valid consent for elective endoscopic procedures’.13 14 It is generally accepted that OGD involves a degree of risk and so written consent should be recorded. Those with adequate training and sufficient knowledge of the procedure and potential complications can obtain consent. Sending information and consent forms through the post, before the procedure may be a practical way of ensuring that patients have enough time to read and consider the required information.26 27 Where an absence of capacity has been demonstrated a decision about whether to perform an OGD in the patient’s best interests should be made by a physician, preferably by the referrer.13

A safety checklist should be completed before starting an OGD.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: moderate

Strength of recommendation: strong

There is a recognised serious complication rate of 3–16% associated with major surgery, of which half of these incidents are thought to be preventable. This triggered the introduction of a 20-point preoperative checklist, as part of the ‘Safe Surgery Saves Lives’ initiative.28 The use of this tool has been tested in a variety of surgical disciplines. More recently, variations of this tool have been adopted in higher-risk medical interventions, including endoscopy.29–33 There is no standardised endoscopy checklist, however, we recommend domains that should be checked before starting an OGD include31 34:

patient identifiers (name/hospital number/date of birth)

allergies

medications/conditions that may preclude any interventions (anticoagulants)

significant comorbidities

patient understanding of proposed test

completion of a consent form.

A checklist should be undertaken after completing an OGD, before the patient leaves the room.

Level of agreement: 90%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

On completing an OGD, the following details should be reviewed and confirmed28:

the number of histological samples taken

the correct labelling of histological samples

the dose of sedation and/or analgesia given

any specific postprocedure advice to be given to the patient

follow-up arrangements.

Procedure quality standards

Only an endoscopist with appropriate training and the relevant competencies should independently perform OGD.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

OGD training is though registration and certification via JAG.3 To attain competence a minimum number of 200 diagnostic procedures must be performed, before a summative assessment using a structured objective assessment tool.3 35 36 At present, although technical competence is assessed, lesion recognition is not a component specifically assessed by the certification process. Lesions of the UGI tract are varied and may be subtle in nature, making quality difficult to measure objectively. We therefore propose that courses on lesion recognition and management form part of the continuing professional development of an UGI endoscopist.37

More experience in lesion recognition is likely to be required in high-risk and surveillance populations. With this in mind, service planning to ensure that patients at increased risk are allocated to an endoscopist with the most relevant experience would be desirable. There is some evidence of increased dysplasia yields associated with dedicated Barrett’s lists.38 Where expertise is not available, referral to a tertiary centre should be considered.39

We suggest that endoscopists should aim to perform a minimum of 100 OGDs a year to maintain a high-quality examination standard.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: weak

It is our opinion that to be able to maintain the ability to perform a high-quality examination, OGDs should be performed regularly. There is no evidence to support a specific minimum number of procedures required to maintain proficiency in OGD once an individual is deemed competent. There are data, mainly from the military and surgical specialties, that breaks in performing any given task results in a ‘skills decay’. The rate at which this occurs depends on the complexity of the task, the duration of the break and the level of previous competency achieved.40–44 In trainees it has been shown that a break in colonoscopy training results in a decline in competency.45 We propose that endoscopists should aim for a minimum of 100 OGDs performed each year to ensure the ability to perform a high-quality diagnostic examination. We accept that some endoscopists perform a large number of therapeutic endoscopies in other aspects of endoscopy while undertaking relatively few diagnostic OGDs. These endoscopists should not be prevented from undertaking UGI endoscopy, but we recommend that their practice is audited as described in these standards.

UGI endoscopy should be performed with high-definition video endoscopy systems, with the ability to capture images and take biopsies.

Level of agreement: 90%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

All diagnostic OGDs should be performed with equipment capable of achieving the intended purpose. As a minimum, endoscopes with the capacity to produce high-definition images should be used. Equipment for obtaining adequate mucosal views and acquisition of histological samples should be available

A complete OGD should assess all relevant anatomical landmarks and high-risk stations.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

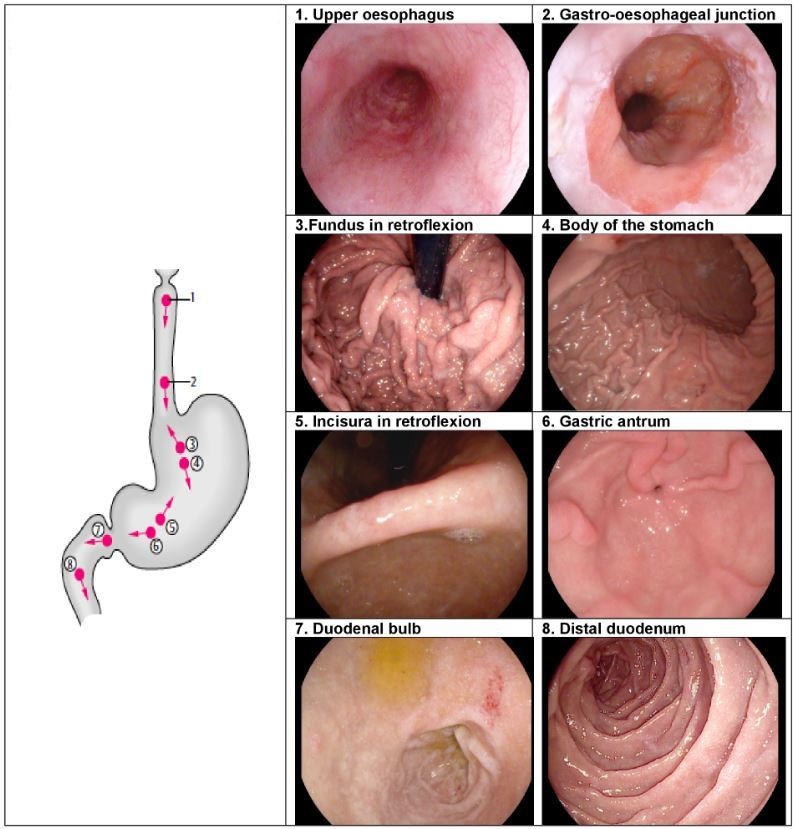

In order to achieve a complete examination of the UGI tract, a standardised set of landmarks should be examined. The procedure should start at the upper oesophageal sphincter and reach the second part of the duodenum, to include the upper oesophagus, gastro-oesophageal junction, fundus, gastric body, incisura, antrum, duodenal bulb and distal duodenum. The fundus should be inspected by a J-manoeuvre in all patients, and where there is a hiatus hernia the diaphragmatic pinch should be inspected while in retroflexion.

Photo-documentation should be made of relevant anatomical landmarks and any detected lesions.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

While there is no evidence to support the practice of photo-documentation, it is intuitive that this practice encourages mucosal cleansing, mucosal inspection and ensures a complete examination. Beyond documentation, freezing an image offers the endoscopist the opportunity to inspect an area of interest, without artefact caused by patient movement. Photo-documentation may also act as a legal record of an adequate/complete procedure. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines describe a systematic approach to photo-documentation (figure 2), with a recommendation of eight anatomical landmarks.46 It is noted that countries that have a higher incidence of gastric cancers have adopted an even more rigorous approach to photo-documentation in order to optimise early diagnosis.47 The widespread availability of electronic image capture systems makes this an achievable goal.48

Figure 2.

A schematic demonstrating the recommended stations for photo-documentation during a diagnostic oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy. (Reproduced with permision from Thieme [43]).

The quality of mucosal visualisation should be reported.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

In order to be able to exclude early UGI lesions, it is necessary to be able to inspect the mucosa, free of bubbles and debris. The quality of views obtained is not routinely stated, in contrast to the reporting of bowel preparation quality during colonoscopy. We propose that the quality of views obtained are rated according to a validated scale and recorded as part of the report.49–51 Where complete views are unattainable, this should be documented, with a recommendation of whether the procedure requires repetition. Where patient agitation or intolerance precludes a complete examination, repeating the OGD with optimal sedation should be considered.

Adequate mucosal visualisation should be achieved by a combination of adequate air insufflation, aspiration and the use of mucosal cleansing techniques.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: moderate

Strength of recommendation: strong

Clear mucosal views can be attained by aspirating debris and washing the mucosal surface by flushing water through the accessory channel of the endoscope. Mucosal cleansing can be made more convenient with the use of a pump-controlled water jet, which allows for the simultaneous use of accessories through the working channel. The addition of mucolytic and defoaming agents such as simethicone, N-acetylcysteine or pronase enables the dispersion of bubbles and mucous. Premedication with a swallowed mucolytic has been shown to reduce the need for washing between procedures and consequently procedure time, as well as appearing to offer superior mucosal views.50 52–59 The optimal timing for preprocedure consumption of these agents appears to be 10–30 min before and so could be incorporated into the admission process.58

It is suggested that the Inspection time during a diagnostic OGD should be recorded for surveillance procedures, such as Barrett’s oesophagus and gastric atrophy/intestinal metaplasia surveillance.

Level of agreement: 90%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: weak

Despite the various tasks that require completion during an allocated endoscopy time slot, the time taken to perform the procedure itself should not be compromised. A high-quality examination, which includes mucosal cleansing and inspection, requires time. It is our opinion that a complete OGD begins after intubation of the upper oesophageal sphincter, then progresses to reach the distal duodenum before a careful withdrawal and inspection starts. The whole procedure should take on average 7 min. A single study has demonstrated that endoscopists taking on average of >7 min for an OGD had a threefold increase in the diagnosis of gastric cancer and dysplasia compared with those taking an average of <7 min to complete the procedure.24 Given the heterogeneity of patients presenting for OGD it is recognised that procedure times will vary. In order to move towards an optimally timed examination, an endoscopist should first be aware of the time spent on the examination. It is therefore our recommendation that the total inspection time for high-risk and surveillance procedures such as Barrett’s oesophagus or gastric atrophy surveillance is recorded and documented as part of the report.

Where a lesion is identified, this should be described using the Paris classification and targeted biopsies taken.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

Universal language in reporting aids decision-making, and thus we would recommend that the morphology of a detected lesion is described according to the Paris classification, with the anatomical location described.60 Photo-documentation should be obtained and targeted biopsy specimens acquired as appropriate.61

Endoscopy units should adhere to safe sedation practice.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

It is recognised that in some patients a high-quality examination may be possible only using sedation and/or analgesia.62 63 Endoscopy units should adhere to pre-existing safe sedation guidelines.64–66 This involves ensuring sedation is given with age and comorbidities in mind, and with appropriate monitoring.67–70 Any occasion where naloxone, flumazenil or ventilation is required owing to oversedation should be recorded and investigated. An internal audit of sedation-related complications and the frequency that sedation is used outside of recommended guidelines, should take place as described by JAG.3

Intravenous sedation and local anaesthetic throat spray can be used in conjunction if required. Caution should be exercised in those at risk of aspiration.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: moderate

Strength of recommendation: strong

There is concern that sedation used in combination with topical anaesthesia increases the likelihood of aspiration pneumonia and postprocedure complications.71–74 Several studies have shown that this combination can improve tolerance and comfort of an OGD.75–82 There is a paucity of evidence as to an increased risk of complications in routine clinical practice. It would be prudent to exercise caution in those with an increased background risk of aspiration, such as the elderly.

Disease-specific quality standards

The length of a Barrett’s segment should be classified according to the Prague classification.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

The Prague classification describes the maximal length and the circumferential extent of the Barrett’s segment, measured on withdrawal of the endoscope.83 This classification has been widely adopted, with good interobserver agreement.84–87 This method of universal reporting means that patients can be stratified according to risk, with their follow-up interval determined in line with existing guidelines.86 This may also assist in determining appropriately timed procedure slots for particularly long segments.

Where a lesion is identified within a Barrett’s segment, this should be described using the Paris classification and targeted biopsies taken.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

Lesions identified within a Barrett’s segment should be considered suspicious until proved otherwise. These should be characterised according to the Paris classification, with their location described by distance from the incisors and clock face position. Targeted biopsy specimens should be taken. Where there is doubt as to the nature of a lesion, multidisciplinary team discussion or referral to a specialist centre may be warranted.

When no lesions are detected within a Barrett’s segment, biopsies should be taken in accordance with the Seattle protocol.

Level of agreement: 90%

Grade of evidence: moderate

Strength of recommendation: strong

Dysplasia within a Barrett’s segment may not always be visible.88 It has been shown that adherence to systematic biopsy protocol throughout the normal appearing mucosa is associated with a greater detection of dysplastic change.89–93 The Seattle protocol involves sampling the Barrett’s segment with quadrantic biopsy specimens taken at 2 cm intervals. Where suspicious areas are identified, these should be imaged and biopsied before the acquisition of non-targeted biopsy specimens. The role for advanced imaging is controversial, but, where available, it can be employed in an attempt to improve lesion detection and characterisation.86

If squamous neoplasia is suspected, full assessment with enhanced imaging and/or Lugol’s chromo-endoscopy is required.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: moderate

Strength of recommendation: strong

Squamous cell oesophageal cancer accounts for more than a quarter of all oesophageal malignancies.94 While lesions may be difficult to visualise with white light endoscopy alone, it has been well established that Lugol’s iodine can aid the detection of dysplastic lesions. This dye is taken up by glycogen, with dysplastic areas relatively glycogen deplete and therefore Lugol void. Suspicious areas appear pale on a dark brown background, before fading to a pink discolouration.95–99 In order to pick up lesions, we would advocate controlled scope withdrawal, inspecting the full length of the oesophagus. Emerging studies propose narrow band imaging as an alternative to Lugol’s chromo-endoscopy. These are encouraging but are yet to be tested in community settings.100–103 Where appropriate imaging cannot be performed locally, referral to a specialist centre is required.

Oesophageal ulcers and oesophagitis that is grade D or atypical in appearance, should be biopsied, with further evaluation in 6 weeks after proton pump inhibitor therapy.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

An observed oesophageal ulcer, defined as a discrete break in the oesophageal mucosa measuring at least 5 mm in diameter, should be described, with the ulcer edge biopsied. A repeat OGD to ensure ulcer healing should be performed 6 weeks later, after high-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy.104 Similarly, where severe oesophagitis is seen, defined as grade D according to the Los Angeles classification,105 biopsy specimens should be taken to exclude underlying dysplasia. In the absence of contraindications a repeat OGD should be performed in 6 weeks to exclude underlying malignancy or Barrett’s oesophagus.

The presence of an inlet patch should be photo-documented.

Level of agreement: 90%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: weak

Heterotopic gastric mucosa proximally within the oesophagus, commonly known as a cervical inlet patch, has a prevalence of approximately 3% in those undergoing OGD.106–109 The clinical significance of this finding is unclear, although it may be associated with an increased frequency of reflux, globus and dysphagia, with several small studies suggesting ablation may result in symptomatic improvement.110–112

Several case reports have demonstrated the presence of dysplastic mucosa within inlet patches, with an estimated incidence of malignancy of 0–1.6%.113–116 While biopsies are helpful to confirm the diagnosis and exclude dysplasia, an inlet patch should not be considered to be a premalignant condition, and there is no evidence to support the acquisition of routine biopsies or surveillance where dysplasia is not found.

Detection of an inlet patch can be used as a surrogate maker of a thorough examination of the oesophagus. As these are most commonly noted just below the upper oesophageal sphincter, an inlet patch can be easily overlooked when rapidly withdrawing the endoscope. Use of narrow band imaging can increase the detection of an inlet patch threefold.117 118

The presence of a hiatus hernia should be documented and measured.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: weak

There are four types of hiatus hernia, with the sliding hiatus hernia accounting for 95% of cases.119 A hernia can be diagnosed endoscopically by establishing that the distance between the top of the gastric folds and the diaphragmatic pinch is ≥2 cm. These measurements are subject to peristalsis, air insufflation and may be difficult to measure accurately in the presence of Barrett’s oesophagus.120 121 A hiatus hernia is best inspected while in retroflexion, allowing for the assessment of both hiatal size and integrity of the oesophagogastric junction (OGJ).122

Biopsies from two different regions in the oesophagus should be taken to rule out eosinophilic oesophagitis in those presenting with dysphagia/food bolus obstruction, where an alternate cause is not found.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: moderate

Strength of recommendation: strong

Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EO) is an immune-mediated condition, characterised by eosinophilic infiltration of the oesophageal mucosa. Diagnosis is confirmed on histology, where ≥15 eosinophils per high power field are detected.123 While EO is an increasingly diagnosed phenomenon, data from population registers suggest an increased incidence and this is not merely due to increased awareness.124 125 Patients typically present with dysphagia or food bolus obstruction. While the characteristic endoscopic findings of trachealisation, white patches, linear furrows and strictures are well described, appearance may be normal in as manay as 15% of sufferers.126–132

Eosinophils are not equally distributed throughout the oesophagus and therefore a false-negative result due to sampling error is possible.133 134 Additionally, diagnostic yield is related to the number of biopsies taken. A single biopsy has a sensitivity of 55%, which increases to close to 100% when six biopsies are taken.134–137 Given that endoscopy can be normal in the presence of EO, we recommend that a total of six biopsies are taken with samples acquired from at least two areas of the oesophagus (lower, mid or upper third), in those presenting with dysphagia where no alternative cause has been identified.

Varices should be described according to a standardised classification.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

Oesophagogastric varices are the most significant of the collaterals produced as a consequence of increased portal pressure, posing a risk of rupture and life-threatening bleeding. Endoscopy is the most accurate method for the assessment of varix size, although grading is subject to interobserver variation.138 Several different classification systems exist. Clinically, differentiation between small and large varices is the most important distinction to make, as this offers the opportunity for prophylactic measures to reduce bleeding risk.139 140 It is recommended that varices are classified according to their size, as grade 1, 2 or 3, in accordance with existing guidelines.138

Strictures should be biopsied to exclude malignancy before dilatation.

Level of agreement: 90%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: weak

Strictures, when first encountered, should not be dilated before histology is obtained to exclude malignancy.141–143 Although it is often possible to determine the nature of a stricture endoscopically, there is a small, theoretical, but unacceptable risk of converting a localised tumour into disseminated disease should a malignant stricture perforate secondary to endoscopic therapy.144 This approach also facilitates diagnosis of the underlying pathology and optimal non-endoscopic therapy—for example, acid suppression for peptic strictures. This approach may not be necessary where there is an established underlying benign aetiology, such as eosinophilic oesophagitis, peptic ulceration, or previous treatment, such as endoscopic mucosal resection or radiofrequency ablation.

Gastric ulcers should be biopsied and re-evaluated after appropriate treatment, including H. pylori eradication where indicated, within 6–8 weeks.

Level of agreement: 90%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

Where a gastric ulcer is seen during an OGD, this should be fully assessed, including a description of the size and location.145 146 Helicobacter pylori status should be assessed by a rapid urease test or gastric biopsies, and if appropriate, eradication therapy should be prescribed.147 A repeat OGD to ensure that the ulcer has healed should be performed 6–8 weeks after the index OGD.148–152

Where there are endoscopic features of gastric atrophy or intestinal metaplasia separate biopsies from the gastric antrum and body should be taken.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: weak

Perhaps owing to a relatively low incidence of gastric cancer in the UK, surveillance of premalignant gastric change is not established. Gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia are thought to give rise to gastric cancer through the inflammation–metaplasia–dysplasia–carcinoma pathway.153 154 Where endoscopic features suggest potential gastric atrophy or metaplasia, representative biopsies should be taken to confirm this diagnosis and to exclude dysplasia. Histological change may be patchy and so the Sydney protocol advocates the acquisition of two non-targeted biopsies from the antrum and body and one from the incisura as separate samples, in addition to targeted biopsies of any visible lesions.155 Careful examination of the stomach with white light endoscopy should be performed as a minimum, with evaluation with chromoendoscopy considered. Where H. pylori is present, this should be eradicated, with evidence suggesting that this may cause a degree of regression of atrophy and delay the progression of intestinal metaplasia.156–159 The surveillance of intestinal metaplasia remains controversial, current ESGE guidelines suggest that 3-yearly surveillance should offered to patients, especially those with a family history or risk factors.155 160 161

Where iron deficiency anaemia is being investigated, separate biopsies from the gastric antrum and body should be taken, as well as duodenal biopsies if coeliac serology is positive or has not been previously measured.

Level of agreement: 80%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: weak

Iron deficiency anaemia has been found to be associated with gastric atrophy. We suggest biopsies are taken from the gastric antrum and body to confirm this diagnosis and avoid further unnecessary investigations. Biopsies from the duodenum should also be taken if coeliac serology is positive or has not been measured before an OGD performed for iron deficiency anaemia.

Where gastric or duodenal ulcers are identified, H. pylori should be tested and eradicated if positive.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: moderate

Strength of recommendation: strong

Where gastric or duodenal ulcers are observed, H. pylori should be excluded by a rapid urease test or gastric biopsies.147 162–164 Medication history should be reviewed to exclude contributory pharmacological agents such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.165 166 There is no role for the surveillance of duodenal ulcers, with repeat OGD having a low diagnostic yield.

The presence of gastric polyps should be recorded, with the number, size, location and morphology described, and representative biopsies taken.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: moderate

Strength of recommendation: strong

The presence, number and size of any detected gastric polyps should be documented. It is recommended that the actual number of polyps is recorded where there are five or less; however, it is acceptable where there are more than five to use the description of multiple polyps. All atypical polyps should be described. The majority of gastric polyps are accounted for by fundic gland and hyperplastic polyps.167–169 Although fundic gland polyps can be predicted with a high degree of accuracy based on endoscopic appearances, biopsies are recommended to confirm the histological diagnosis and exclude dysplasia.170 171 A single biopsy of a polyp is usually sufficient, with this approach having been found to be as accurate as polypectomy in 97.3% of cases.172 Repeat biopsies of a previously diagnosed benign gastric polyps are not indicated.171 Where there are multiple polyps, representative biopsies should be taken, as it is known that coexisting polyps are usually of the same histological type.173 Premalignant polyps should undergo surveillance in accordance with existing guidelines, while some dysplastic polyps should be considered for removal.171

It should be noted that approximately 30–50% of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis have adenomas in the stomach and up to 90% in the duodenum.174 175 Often these patients have a carpet of fundic gland polyps in the proximal stomach making it technically challenging to identify the adenomatous change.175 The diagnosis and surveillance of familial adenomatous polyposis in the UGI tract should follow in accordance with published guidelines.174

Where coeliac disease is suspected, a minimum of four biopsies should be taken, including representative biopsies from the second part of the duodenum and at least one from the duodenal bulb.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: strong

Strength of recommendation: strong

Coeliac disease is an autoimmune condition, characterised by gluten-induced small bowel villous atrophy. Classic endoscopic features of flattened mucosal appearance, nodularity, a reduction in duodenal folds and scalloping have been described. Coeliac disease may be present in the absence of endoscopic features and therefore biopsies to obtain a histological diagnosis where there is a suspicion of coeliac disease are recommended.176–179 Villous atrophy may occur in a patchy distribution and so in order to optimise diagnosis a minimum of four biopsies taken at different locations throughout the duodenum, including the bulb, are required.180–184 Where an OGD is being performed specifically to obtain histological confirmation of coeliac disease, patients should adhere to a gluten-rich diet to avoid a false-negative result, consuming gluten in more than one meal a day for at least 6 weeks.185 Once a diagnosis has been established, management should be in accordance with existing guidelines.182 185

A malignant looking lesion should be photo-documented and a minimum of six biopsies taken.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

A standardised approach to reporting malignant lesions enables the planning of potential endoscopic therapy and, where this is not possible, this may guide surgical or palliative measures. As a minimum, a report should describe the anatomical location, including the distance from a fixed landmark, (eg, from the incisors), number, size and morphology of any lesions as well as any abnormalities of the background mucosa.

There is little evidence for the optimal number of biopsies required to ensure a diagnosis where malignancy is present.186 187 Accepted convention is to obtain at least six representative biopsies of the lesion in question. This would appear to be an appropriate number given the biopsy protocols used for other pathologies of the gastrointestinal tract and in view of the importance of establishing a prompt diagnosis of malignancy without the need for repeated examinations. In addition to confirming a diagnosis, it may be necessary to obtain sufficient tissue to perform additional techniques, which may influence treatment options, such as HER2 testing.188–190 Acquisition of fewer biopsies may need to be considered in individual patients—for example, those who are being anticoagulated, those with bleeding diathesis, or on the basis of lesion characteristics.

Methods for early escalation of malignant lesions to an upper gastrointestinal multidisciplinary team meeting should be in place. This will usually be in the form of a team to which an endoscopist can refer a patient following the detection of a potentially malignant lesion.

Postprocedure quality standards

After OGD readmission, mortality and complications should be audited.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

Complications related to the procedure or associated with the use of sedation should be audited annually. Units should record the 8-day readmission rate and 30-day mortality after OGD in accordance with standards set out byJAG.3 After a procedure verbal and written instructions should be given to patients, with advice about when, where and how to seek medical attention if required. 3

A report summarising the endoscopy findings and recommendations should be produced and the key information provided to the patient before discharge.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

A report describing the main findings of the OGD and key recommendations should be produced contemporaneously. This should include the extent of the examination, any abnormal findings, documentation of any samples taken and the proposed management plan, including the need for any further endoscopy or imaging.191–193 Where surveillance is required—for example, in Barrett’s oesophagus, the recommended interval should be specified. Any instructions to the patient about changes in medication, pending results or follow-up should be recorded. Where appropriate, the patient should be offered a copy of the written report, with an opportunity to ask questions. This report should be made available to the referring physician and GP within 24 hours. Where an endoscopy has taken place outside of the endoscopy department or out of hours, a written report in the patient notes is sufficient until an official report can be issued at the earliest time practical.

A method for ensuring histological results are processed must be in place.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

Histology results taken during endoscopic procedures should be promptly reviewed.3 Where an unsuspected case of high-grade dysplasia or malignancy is detected on histological review, this should also be highlighted to the relevant multidisciplinary team by the histopathologist.

Endoscopy units should audit rates of failing to diagnose cancer at endoscopy up to 3 years before an oesophago-gastric cancer is diagnosed.

Level of agreement: 100%

Grade of evidence: weak

Strength of recommendation: strong

An UGI cancer detected within 3 years of an OGD should be considered as a failure to diagnose the cancer earlier (termed post OGD UGI cancer or POUGIC). Retrospective studies have shown that the rate of POUGIC ranges between 4.6% and 14.4%.4 6 194–197 We recommend that units audit performance data to ensure that POUGIC rates do not exceed 10% and a root cause analysis of factors contributing to individual cases is performed. We suggest that this evaluation is performed every 3 years, in order to have sufficient POUGIC cases to compare against the set standard. Prospective collection of this data at the point of a patient’s referral to an UGI multidisciplinary team may be a practical way of ensuring these data are collected.

Conclusions

It is hoped that with the institution of the above recommendations there will be a focus on improving quality in diagnostic UGI endoscopy. Key performance indicators have been determined from the above recommendations (figure 2), which should be instituted, measured and audited within departments. Improvement will be confirmed by an increased rate of early detection of neoplasia and a reduced incidence of interval cancers.

Footnotes

Contributors: SB (joint first author): systematic review of the evidence, author of the manuscript and coordinator of the process. KR (joint first author): formulation of KPIs, review and voting on evidence, review and contribution to the manuscript, overseeing the process. AW (AUGIS representative), MB, NT, DMP, SR, JA, HG, PB, AV: formulation of KPIs, review and voting on evidence, review and contribution to the manuscript. PK (histopathology representative): review and contribution to the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Barrison I, Bramble M, Wilkinson M. Provision of endoscopy related services in district general hospitals: British Society of Gastroenterology. Endoscopy Committee 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.England PH. National Cancer intelligence Network be clear on Cancer: oesophago-gastric cancer awareness regional pilot campaign: Interim evaluation report, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint advisory group on GI endoscopy http://www.thejag.org.uk.

- 4.Chadwick G, Groene O, Hoare J, et al. . A population-based, retrospective, cohort study of esophageal cancer missed at endoscopy. Endoscopy 2014;46:553–60. 10.1055/s-0034-1365646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veitch AM, Uedo N, Yao K, et al. . Optimizing early upper gastrointestinal cancer detection at endoscopy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:660–7. 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menon S, Trudgill N. How commonly is upper gastrointestinal Cancer missed at endoscopy? A meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open 2014;2:E46–E50. 10.1055/s-0034-1365524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chadwick G, Groene O, Riley S, et al. . Gastric cancers missed during Endoscopy in England. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1264–70. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bisschops R, Areia M, Coron E, et al. . Performance measures for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a european Society of gastrointestinal endoscopy quality improvement initiative. United European Gastroenterol J 2016;4:629–56. 10.1177/2050640616664843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.PLUS MA. AGREE II Instrument.

- 10.Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, et al. . The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club 1995;123:A12–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalkey NC, Brown BB, Cochran S. The Delphi method: an experimental study of group opinion. CA: Rand Corporation Santa Monica., 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veitch AM, Vanbiervliet G, Gershlick AH, et al. . Endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, including direct oral anticoagulants: british Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and european society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines. Endoscopy 2016;48:385–402. 10.1055/s-0042-102652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Council GM. Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together: general Medical Council, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepherd H, Hewett D. Guidance for obtaining a Valid Consent for Elective Endoscopic Procedures: British Society of Gastroenterology, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clements H, Melby V. An investigation into the information obtained by patients undergoing gastroscopy investigations. J Clin Nurs 1998;7:333–42. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1998.00161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayberry MK, Mayberry JF. Towards better informed consent in endoscopy: a study of information and consent processes in gastroscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001;13:1467–76. 10.1097/00042737-200112000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toomey DP, Hackett-Brennan M, Corrigan G, et al. . Effective communication enhances the patients' endoscopy experience. Ir J Med Sci 2016;185:203–14. 10.1007/s11845-015-1270-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy N, Landmann L, Stermer E, et al. . Does a detailed explanation prior to gastroscopy reduce the patient’s anxiety? Endoscopy 1989;21:263–5. 10.1055/s-2007-1012965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aabakken L, Baasland I, Lygren I, et al. . Development and evaluation of written patient information for endoscopic procedures. Endoscopy 1997;29:23–6. 10.1055/s-2007-1004056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felley C, Perneger TV, Goulet I, et al. . Combined written and oral information prior to gastrointestinal endoscopy compared with oral information alone: a randomized trial. BMC Gastroenterol 2008;8:22 10.1186/1471-230X-8-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bytzer P, Lindeberg B. Impact of an information video before colonoscopy on patient satisfaction and anxiety - a randomized trial. Endoscopy 2007;39:710–4. 10.1055/s-2007-966718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trevisani L, Sartori S, Gaudenzi P, et al. . Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: are preparatory interventions or conscious sedation effective? A randomized trial. World J Gastroenterol 2004;10:3313–7. 10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bassi A, Brown E, Kapoor N, et al. . Dissatisfaction with consent for diagnostic gastrointestinal endoscopy. Dig Dis 2002;20:275–9. 10.1159/000067680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teh JL, Tan JR, Lau LJ, et al. . Longer examination time improves detection of gastric cancer during diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:e2:480–7. 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta N, Gaddam S, Wani SB, et al. . Longer inspection time is associated with increased detection of high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;76:531–8. 10.1016/j.gie.2012.04.470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shepherd HA, Bowman D, Hancock B, et al. . Postal consent for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut 2000;46:37–9. 10.1136/gut.46.1.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sidhu R, Sakellariou V, Layte P, et al. . Patient feedback on helpfulness of postal information packs regarding informed consent for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;64:229–34. 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lancet T. WHO’s patient-safety checklist for surgery. Lancet 2008;372:1 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60964-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silver SA, Thomas A, Rathe A, et al. . Development of a hemodialysis safety checklist using a structured panel process. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2015;2:39 10.1186/s40697-015-0039-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hale G, McNab D. Developing a ward round checklist to improve patient safety. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2015;4:u204775.w2440–w2440. 10.1136/bmjquality.u204775.w2440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matharoo M, Thomas-Gibson S, Haycock A, et al. . Implementation of an endoscopy safety checklist. Frontline Gastroenterol 2014;5:260–5. 10.1136/flgastro-2013-100393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hazelton JP, Orfe EC, Colacino AM, et al. . The impact of a multidisciplinary safety checklist on adverse procedural events during bedside bronchoscopy-guided percutaneous tracheostomy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79:111–6. 10.1097/TA.0000000000000700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong SS, Cleverly S, Tan KT, et al. . Impact and culture change after the implementation of a preprocedural checklist in an interventional radiology department. J Patient Saf 2015:1 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matharoo M, Sevdalis N, Thillai M, et al. . The endoscopy safety checklist: A longitudinal study of factors affecting compliance in a tertiary referral centre within the United Kingdom. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2015;4:u206344.w2567 10.1136/bmjquality.u206344.w2567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cass OW. Objective evaluation of competence: technical skills in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy 1995;27:86–9. 10.1055/s-2007-1005640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vassiliou MC, Kaneva PA, Poulose BK, et al. . How should we establish the clinical case numbers required to achieve proficiency in flexible endoscopy? Am J Surg 2010;199:121–5. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Q, Chen ZY, Chen CD, et al. . Training in early gastric cancer diagnosis improves the detection rate of early gastric cancer: an observational study in China. Medicine 2015;94:e384 10.1097/MD.0000000000000384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ooi J, Wilson P, Walker G, et al. . Dedicated Barrett’s surveillance sessions managed by trained endoscopists improve dysplasia detection rate. Endoscopy 2017;49:C1 10.1055/s-0043-109623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anagnostopoulos GK, Pick B, Cunliffe R, et al. . Barrett’s esophagus specialist clinic: what difference can it make? Dis Esophagus 2006;19:84–7. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00545.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ginzburg S, Dar‐El EM. Skill retention and relearning – a proposed cyclical model. J Workplace Learn 2000;12:327–32. 10.1108/13665620010378822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bailey CD. Forgetting and the learning curve: a laboratory study. Manage Sci 1989;35:340–52. 10.1287/mnsc.35.3.340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perez RS, Skinner A, Weyhrauch P, et al. . Prevention of surgical skill decay. Mil Med 2013;178:76–86. 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snyder CW, Vandromme MJ, Tyra SL, et al. . Retention of colonoscopy skills after virtual reality simulator training by independent and proctored methods. Am Surg 2010;76:743–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chamberlain D, Smith A, Woollard M, et al. . Trials of teaching methods in basic life support (3): comparison of simulated CPR performance after first training and at 6 months, with a note on the value of re-training. Resuscitation 2002;53:179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jorgensen JE, Elta GH, Stalburg CM, et al. . Do breaks in gastroenterology fellow endoscopy training result in a decrement in competency in colonoscopy? Gastrointest Endosc 2013;78:503–9. 10.1016/j.gie.2013.03.1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rey JF, Lambert R. ESGE Quality Assurance Committee. ESGE recommendations for quality control in gastrointestinal endoscopy: guidelines for image documentation in upper and lower GI endoscopy. Endoscopy 2001;33:901–3. 10.1055/s-2001-42537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yao K. The endoscopic diagnosis of early gastric cancer. Annals of Gastroenterology 2012;26:11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murad FM, Banerjee S, Barth BA, et al. . Image management systems. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;79:15–22. 10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asl SM, Sivandzadeh GR. Efficacy of premedication with activated dimethicone or N-acetylcysteine in improving visibility during upper endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:4213–7. 10.3748/wjg.v17.i37.4213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuo CH, Sheu BS, Kao AW, et al. . A defoaming agent should be used with pronase premedication to improve visibility in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy 2002;34:531–4. 10.1055/s-2002-33220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang CC, Chen SH, Lin CP, et al. . Premedication with pronase or N-acetylcysteine improves visibility during gastroendoscopy: an endoscopist-blinded, prospective, randomized study. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:444 10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neale JR, James S, Callaghan J, et al. . Premedication with N-acetylcysteine and simethicone improves mucosal visualization during gastroscopy: a randomized, controlled, endoscopist-blinded study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;25:778–83. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32836076b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asl S, Sivandzadeh GR. Efficacy of premedication with activated dimethicone or N-acetylcysteine in improving visibility during upper endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:4213 10.3748/wjg.v17.i37.4213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhandari P, Green S, Hamanaka H, et al. . Use of gascon and pronase either as a pre-endoscopic drink or as targeted endoscopic flushes to improve visibility during gastroscopy: a prospective, randomized, controlled, blinded trial. Scand J Gastroenterol 2010;45:357–61. 10.3109/00365520903483643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang CC, Chen SH, Lin CP, et al. . Premedication with pronase or N-acetylcysteine improves visibility during gastroendoscopy: an endoscopist-blinded, prospective, randomized study. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:444–7. 10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee SY, Han HS, Cha JM, et al. . Endoscopic flushing with pronase improves the quantity and quality of gastric biopsy: a prospective study. Endoscopy 2014;46:747–53. 10.1055/s-0034-1365811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fujii T, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, et al. . Effectiveness of premedication with pronase for improving visibility during gastroendoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc 1998;47:382–7. 10.1016/S0016-5107(98)70223-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woo JG, Kim TO, Kim HJ, et al. . Determination of the optimal time for premedication with pronase, dimethylpolysiloxane, and sodium bicarbonate for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:389–92. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182758944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen HW, Hsu HC, Hsieh TY, et al. . Pre-medication to improve esophagogastroduodenoscopic visibility: a meta-analysis and systemic review. Hepatogastroenterology 2014;61:1642–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Inoue H, Kashida H, Kudo S, et al. . The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;58(6 Suppl):S3–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aabakken L, Barkun AN, Cotton PB, et al. . Standardized endoscopic reporting. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:234–40. 10.1111/jgh.12489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McQuaid KR, Laine L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of moderate sedation for routine endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;67:910–23. 10.1016/j.gie.2007.12.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meining A, Semmler V, Kassem AM, et al. . The effect of sedation on the quality of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: an investigator-blinded, randomized study comparing propofol with midazolam. Endoscopy 2007;39:345–9. 10.1055/s-2006-945195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.NCEPOD. Scoping our practice: the 2004 Report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Waring JP, Baron TH, Hirota WK, et al. . Guidelines for conscious sedation and monitoring during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;58:317–22. 10.1067/S0016-5107(03)00001-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riphaus A, Wehrmann T, Weber B, et al. . S3 guideline: sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy 2008. Endoscopy 2009;41:787–815. 10.1055/s-0029-1215035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lord D, Bell G, Gray A, et al. . Sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures in the elderly: getting safer but still not nearly safe enough. The British Society of Gastroenterology Website 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Colleges AoMR. Safe Sedation Practice for Healthcare Procedures, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Triantafillidis JK, Merikas E, Nikolakis D, et al. . Sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy: current issues. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:463–81. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Richter JM, Kelsey PB, Campbell EJ. Adverse event and complication management in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:348–52. 10.1038/ajg.2015.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Quine MA, Bell GD, McCloy RF, et al. . Prospective audit of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in two regions of England: safety, staffing, and sedation methods. Gut 1995;36:462–7. 10.1136/gut.36.3.462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prout BJ, Metreweli C. Pulmonary aspiration after fibre-endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Br Med J 1972;4:269–71. 10.1136/bmj.4.5835.269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Byrne MF, Mitchell RM, Gerke H, et al. . The need for caution with topical anesthesia during endoscopic procedures, as liberal use may result in methemoglobinemia. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004;38:225–9. 10.1097/00004836-200403000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brown CM, Levy SA, Susann PW. Methemoglobinemia: life-threatening complication of endoscopy premedication. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:1108–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Campo R, Brullet E, Montserrat A, et al. . Topical pharyngeal anesthesia improves tolerance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a randomized double-blind study. Endoscopy 1995;27:659–64. 10.1055/s-2007-1005783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Davis DE, Jones MP, Kubik CM. Topical pharyngeal anesthesia does not improve upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in conscious sedated patients. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1853–6. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lachter J, Jacobs R, Lavy A, et al. . Topical pharyngeal anesthesia for easing endoscopy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc 1990;36:19–21. 10.1016/S0016-5107(90)70915-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Froehlich F, Schwizer W, Thorens J, et al. . Conscious sedation for gastroscopy: patient tolerance and cardiorespiratory parameters. Gastroenterology 1995;108:697–704. 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90441-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gordon MJ, Mayes GR, Meyer GW. Topical lidocaine in preendoscopic medication. Gastroenterology 1976;71:564–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cantor DS, Baldridge ET. Premedication with meperidine and diazepam for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy precludes the need for topical anesthesia. Gastrointest Endosc 1986;32:339–41. 10.1016/S0016-5107(86)71879-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Evans LT, Saberi S, Kim HM, et al. . Pharyngeal anesthesia during sedated EGDs: is “the spray” beneficial? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:761–6. 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ristikankare M, Hartikainen J, Heikkinen M, et al. . Is routine sedation or topical pharyngeal anesthesia beneficial during upper endoscopy? Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60:686–94. 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02048-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, et al. . The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett’s esophagus: the Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology 2006;131:1392–9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dunn SJ, Neilson LJ, Hassan C, et al. . ESGE Survey: worldwide practice patterns amongst gastroenterologists regarding the endoscopic management of Barrett’s esophagus. Endosc Int Open 2016;4:E36–E41. 10.1055/s-0034-1393247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alvarez Herrero L, Curvers WL, van Vilsteren FG, et al. . Validation of the Prague C&m classification of Barrett’s esophagus in clinical practice. Endoscopy 2013;45:876–82. 10.1055/s-0033-1344952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, et al. . British Society of Gastroenterology. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2014;63:7–42. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vahabzadeh B, Seetharam AB, Cook MB, et al. . Validation of the Prague C & M criteria for the endoscopic grading of Barrett’s esophagus by gastroenterology trainees: a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:236–41. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reid BJ, Weinstein WM, Lewin KJ, et al. . Endoscopic biopsy can detect high-grade dysplasia or early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus without grossly recognizable neoplastic lesions. Gastroenterology 1988;94:81–90. 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90613-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Abela JE, Going JJ, Mackenzie JF, et al. . Systematic four-quadrant biopsy detects Barrett’s dysplasia in more patients than nonsystematic biopsy. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:850–5. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Abrams JA, Kapel RC, Lindberg GM, et al. . Adherence to biopsy guidelines for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance in the community setting in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:736–42. 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Das D, Ishaq S, Harrison R, et al. . Management of Barrett’s esophagus in the UK: overtreated and underbiopsied but improved by the introduction of a national randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1079–89. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01790.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fitzgerald RC, Saeed IT, Khoo D, et al. . Rigorous surveillance protocol increases detection of curable cancers associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Dig Dis Sci 2001;46:1892–8. 10.1023/A:1010678913481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Peters FP, Curvers WL, Rosmolen WD, et al. . Surveillance history of endoscopically treated patients with Early Barrett’s neoplasia: nonadherence to the Seattle biopsy protocol leads to sampling error. Dis Esophagus 2008;21:475–9. 10.1111/j.1442-2050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Arnold M, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, et al. . Global incidence of oesophageal cancer by histological subtype in 2012. Gut 2015;64:381–7. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mori M, Adachi Y, Matsushima T, et al. . Lugol staining pattern and histology of esophageal lesions. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:701–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Inoue H, Rey JF, Lightdale C. Lugol chromoendoscopy for esophageal squamous cell cancer. Endoscopy 2001;33:75–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shimizu Y, Omori T, Yokoyama A, et al. . Endoscopic diagnosis of early squamous neoplasia of the esophagus with iodine staining: high-grade intra-epithelial neoplasia turns pink within a few minutes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:546–50. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04990.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ishihara R, Yamada T, Iishi H, et al. . Quantitative analysis of the color change after iodine staining for diagnosing esophageal high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:213–8. 10.1016/j.gie.2008.04.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dubuc J, Legoux J-, Winnock M, et al. . Endoscopic screening for esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma in high-risk patients: a prospective study conducted in 62 French endoscopy centers. Endoscopy 2006;38:690–5. 10.1055/s-2006-925255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ide E, Maluf-Filho F, Chaves DM, et al. . Narrow-band imaging without magnification for detecting early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:4408–13. 10.3748/wjg.v17.i39.4408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lecleire S, Antonietti M, Iwanicki-Caron I, et al. . Lugol chromo-endoscopy versus narrow band imaging for endoscopic screening of esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma in patients with a history of cured esophageal cancer: a feasibility study. Dis Esophagus 2011;24:418–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chai TH, Jin XF, Li SH, et al. . A tandem trial of HD-NBI versus HD-WL to compare neoplasia miss rates in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 2014;61:120–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]