Abstract

Background

Cervical cancer incidence in the US-Affiliated Pacific Islands (USAPIs) is double that of the US mainland. American Samoa, Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), Guam and the Republic of Palau receive funding from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) to implement cervical cancer screening to low-income, uninsured or under insured women. The USAPI grantees report data on screening and follow-up activities to the CDC.

Materials and methods

We examined cervical cancer screening and follow-up data from the NBCCEDP programs in the four USAPIs from 2007 to 2015. We summarized screening done by Papanicolaou (Pap) and oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) tests, follow-up and diagnostic tests provided, and histology results observed.

Results

A total of 22,249 Pap tests were conducted in 14,206 women in the four USAPIs programs from 2007–2015. The overall percentages of abnormal Pap results (low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions or worse) was 2.4% for first program screens and 1.8% for subsequent program screens. Histology results showed a high proportion of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (57%) among women with precancers and cancers. Roughly one-third (32%) of Pap test results warranting follow-up had no data recorded on diagnostic tests or follow-up done.

Conclusion

This is the first report of cervical cancer screening and outcomes of women served in the USAPI through the NBCCEDP with similar results for abnormal Pap tests, but higher proportion of precancers and cancers, when compared to national NBCCEDP data. The USAPI face significant challenges in implementing cervical cancer screening, particularly in providing and recording data on diagnostic tests and follow-up. The screening programs in the USAPI should further examine specific barriers to follow-up of women with abnormal Pap results and possible solutions to address them.

Keywords: US-Affiliated Pacific Islands, Cervical cancer, Screening, NBCCEDP, US territories

1. Introduction

The US-Affiliated Pacific Islands (USAPI) are comprised of three US flag jurisdictions: territories of American Samoa, Guam, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), and three Freely Associated States: the Republic of Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) and the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) (Fig. 1). The USAPI are populated by more than 450,000 people living on hundreds of islands and atolls, occupying greater than one million ocean square miles, and crossing five Pacific Time zones and the International Date Line [1]. Cervical cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer death in women in the USAPI and cervical cancer incidence in the USAPIs (20.6 per 100,000) was more than two-fold that in the US mainland (7.8 per 100,000) between 2007 and 2011 [2,3]. There is limited population-level data on cervical cancer screening in the USAPI jurisdictions, but screening coverage estimates are generally lower than in the US mainland. The percentage of women who had a Papanicolaou (Pap) test in the past 5 years was reported to be 55% in Palau in 2006, and 53.5% in CNMI in 2015, compared to 88.6% in the US mainland in 2012 [3–5].

Fig. 1.

Map of the six US- Affiliated Pacific Islandsa.

aThe National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) was implemented in four US–Affiliated Pacific Islands between 2007 and 2015: American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and the Republic of Palau.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC)’s National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) provides funding to US states, tribes and territories to deliver breast and cervical cancer screening to low-income, uninsured or under insured women [6]. The NBCCEDP is a collection of individual programs that operate within a national program framework of legislation, policy, and oversight. Each state/territory grantee establishes an operational model unique to their public health infrastructure that includes strategies to reach eligible women in underserved communities and a provider network to deliver services. Program implementation decisions are made by states/territories and vary among grantees [7]. Four USAPI territories receive NBCCEDP funding: American Samoa (1998-present), Guam (2002-present), Palau (1998-present) and CNMI (1998–2002, 2007-present). The screening programs in the four USAPIs follow screening recommendations from the U.S Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); women aged 21–65 years are screened using a Pap test every 3 years, or every 5 years if an oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) test is administered with a Pap test (co-testing) for women aged 30–65 years [8]. These USPSTF recommendations for cervical cancer screening were released in March 2012, and CDC asked grantees to implement them by July 2012. Prior to 2012, screening programs in the USAPI followed previous USPSTF screening recommendations that did not include HPV testing, and allowed for screening of women under the age of 21, based on age of onset of sexual activity [9]. The screening programs in the USAPI adhere to the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) guidelines for follow-up of women with abnormal Pap results [10]. In addition to the NBCCEDP, government support for cervical cancer screening in the USAPI is also provided by the Title X Family Planning program, the Maternal Child Health program and the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) Community Health Center Program (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands receiving support for cervical cancer screening through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program.

| American Samoa | Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) | Guam | The Republic of Palau | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political status with U.S. | Territory | Commonwealth | Territory | Freely Associated |

| Population (est. 2012)a,b | 55, 519 | 53, 883 | 159, 358 | 20,518 |

| Number of islands | 7 (5 inhabited) | 14 (most residents live on 3 islands) | 1 | 340 (9 inhabited) |

| Number of eligible women age 20–64b | 13,776 | 16, 398 | 44,123 | 5215 |

| Cervical Cancer Screening Resources | ||||

| NBCCEDP (CDC) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Title X – Family Planning (HHS) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Community health centers (HRSA) | 3 sites | 1 site | 2 sites | 4 sites |

| MCH Block Grant (HRSA) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Local cervical pathology lab services availablec,d | No | No | No | No |

| Number of cytopathologists/pathologistsc | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/1 | 0/0 |

| Referral practices for women with positive screening test results who require treatmentc | Referral to LBJ Tropical Medical Center; Hawaii | Referral to community health center; Philippines, or Hawaii | Referral to Medical Social Services; Philippines, or Hawaii | Philippines, or Hawaii |

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NBCCEDP, National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, HHS, US Department of Health and Human Services; HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration; MCH, Maternal and Child Health, LBJ Tropical Medical Center, Lyndon B. Johnson Tropical Medical Center in American Samoa.

US Census Bureau; 2010 Census Island Areas [updated August 2013]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/2010census/news/press-kits/island-areas/island-areas.html. Accessed 12/6/2016.

Office on Women’s Health. Quick Health Data Online. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012. Health Status of Women in Region IX. Available at: http://52.207.219.3/qhdo/Reg09%20Report.pdf. Accessed 12/06/2016.

Ref. [14].

Personal Communication 12/6/2016 with NBCCEDP Program Staff from the US-Affiliated Pacific Islands.

Cervical cancer screening programs in the USAPI face several technical, geographical and socioeconomic challenges in providing screening and treatment for precancerous and cancerous cervical lesions. None of the USAPIs have a certified laboratory to process Pap or HPV screening tests on-island; currently all CDC-funded screening programs in the USAPI ship their specimens to laboratories in Los Angeles or Hawaii for testing. Screening programs have to pay high shipping costs for the specimens and wait longer to receive results (turnaround time of up to one-month) (NBCCEDP program staff in the USAPI, personal communication, December 6, 2016). Follow-up of women with abnormal results is challenging since there is no public transportation on most islands, and some women live on outer islands or atolls with limited ship or air transportation to health centers on the main islands for multiple visits [11]. American Samoa, Palau and CNMI have a combined total of 17 vastly dispersed outer islands with women served by the NBCCEDP. Treatment of women with precancerous cervical lesions is limited by lack of medical grade carbon dioxide for cryotherapy or the inability to perform loop electrosurgical excision procedures (LEEPs) on-island [11].

In spite of all these challenges, the CDC-funded screening programs in the four USAPIs have been providing cervical cancer screening to women for the last 15 years. In this analysis, we examine the cervical cancer screening and diagnostic services provided, and outcomes observed in women served by the NBCCEDP in the four USAPI jurisdictions from 2007 to 2015. We limited our analysis to 2007–2015 since all four USAPI jurisdictions received NBCCEDP funding continuously during this period.

2. Methods

The CDC collects a standardized set of data variables, referred to as the Minimum Data Elements (MDEs), to monitor the implementation and results of the NBCCEDP’s screening, diagnostic and follow-up activities (OMB # 0920-0571). The composition and quality of the MDEs been previously described in-detail elsewhere [12,13]. For this analysis, we examined MDEs from the four funded USAPIs: American Samoa, CNMI, Guam and the Republic of Palau, from 2007 to 2015. This study was approved by CDC’s Institutional Review Board.

The MDEs contain information on cervical cancer screening by Pap test and by oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) testing; women enrolled in the NBCCEDP are assigned a unique identification number to track screening and diagnostic services provided to them over time. Pap test results for the 2007–2015 period were reported using the Bethesda 2001 system categories [14]. We present the total number of Pap tests conducted by the four USAPIs each calendar year, the range of total Pap tests conducted per island, as well as the range of total unduplicated women screened by Pap test per island. We examined Pap test results by age, calculated using birth date reported at enrollment, and classified into 6 age categories: 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–64 and 65 years and older. We examined the percentage of women with abnormal Pap test results, defined as results of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) or worse. We also examined Pap test results for women’s first screen in the NBCCEDP (first round) and for all subsequent screens in the time period (subsequent rounds).

Two of the four USAPIs performed HPV testing (triage or co-testing) between 2007 and 2015; we summarized the total number of HPV tests conducted each year, as well as the range of total HPV tests conducted per island each year. In 2012, the USPSTF recommendations included the administration of HPV testing along with Pap testing (co-testing) in women 30–65 years [8]. The NBCCEDP asked states and territories to implement the new screening recommendation, including co-testing, by July 2012. HPV test data reported prior to the implementation of co-testing in the NBCCEDP in 2012 was from testing done to triage abnormal Pap test results. HPV data after July 2012 includes both triage and co-testing.

We examined follow-up and diagnostic tests conducted within each cervical cancer screening cycle, which was defined as the time between the Pap test date and the date of the diagnostic test or 6 months after the end of the screening calendar year. The categories for diagnostic procedures were: colposcopy with directed biopsy, colposcopy without biopsy, endocervical curettage alone (ECC), loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), cold knife conization and other procedures. The ‘Other’ category indicates gynecologic visits made by women, but records did not specify the type of diagnostic tests or procedures done during the visit. We examined the number of follow-up and diagnostic test procedures by Pap and HPV testing done.

We also examined the percentage of biopsy-confirmed precancers or cancers for women screened in the program by self-reported age and race, first versus subsequent screening, and screening year. Histology results were categorized as low-grade CIN (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 1), high-grade CIN (CIN2 or CIN3) and invasive cervical cancer (ICC). We examined the rates of the biopsy-confirmed precancers or cancers per 1000 Pap tests based on the women’s most severe outcomes during the study period. Due to the relatively small numbers in the low-grade CIN, high-grade CIN and ICC categories, we did not perform any statistical tests to compare rates across categories of any of the descriptive variables.

3. Results

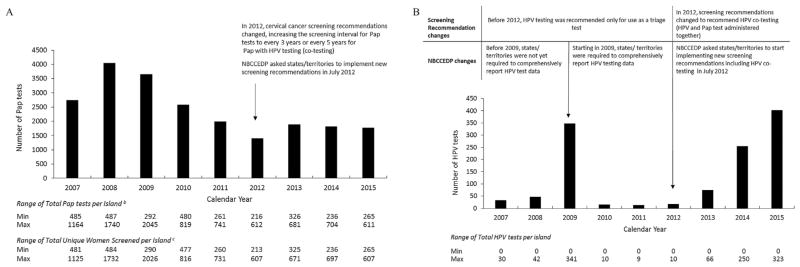

A combined total of 22, 249 Pap tests were conducted in 14,206 women by the four USAPI grantees between 2007 and 2015. The total number of Pap tests conducted was highest in 2008 (total = 4043 Pap tests), and notably decreased yearly from 2009 through 2012. (Fig. 2a). Two of the four USAPIs performed HPV testing for triage or co-testing between 2007 and 2015 and overall, very few HPV tests (total = 1203 HPV tests) were performed by these two islands, in comparison to Pap tests conducted during this period (Fig. 2b). An increase in HPV tests conducted was observed for 2009 when NBCCEDP required states to start reporting HPV test data comprehensively. The total number of HPV tests conducted every year increased annually between 2012 and 2015.

Fig. 2.

(a) Total number of Papanicolaou (Pap) tests provided by the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program by year in four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands, 2007–2015a.

aThe National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) was implemented in four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands between 2007 and 2015: American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and the Republic of Palau.

bTotals exclude Pap tests with unsatisfactory/other results.

cTotals exclude women with unsatisfactory/other Pap test results

(b) Total number of human papillomavirus(HPV) tests provided by the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program by year in four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands, 2007–2015.

aThe National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) was implemented in four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands between 2007 and 2015: American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and the Republic of Palau. Only two of the four USAPIs performed HPV testing between 2007 and 2015.

Abbreviations: Pap test, Papanicolaou Test.

Pap test results for the first program screen and subsequent program screens are shown in (Table 2). The overall percentage of abnormal Pap test results in the first round was 2.4%, and appeared to decrease in subsequent screening rounds to 1.8%. In both first and subsequent round screenings, the percentage of abnormal Pap results generally decreased with increasing age, with the highest percentage in women aged 18–29 years, and the lower percentages in women aged 50–59, 60–64 and 65 years or older. The decrease in the percentage of abnormal Pap tests in subsequent screening rounds was seen for older women, but little or no difference was seen for women 59 years and younger. The overall percentage of results found to be atypical squamous cells of unknown significance (ASC-US) or unsatisfactory appeared to increase in subsequent screens compared to the first screening round.

Table 2.

Distribution of Papanicolaou (Pap) Test Results by Age Group and Screening Round in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program for four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands, 2007–2015.a

| All | Age (y) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 18–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–64 | ≥65 | ||

| First Program Screening Round | |||||||

| Total Pap tests (n) | 10,933 | 2496 | 2883 | 2992 | 1910 | 441 | 211 |

| Results (%)b | |||||||

| Normal | 95.0 | 92.7 | 94.8 | 95.4 | 97.3 | 95.7 | 97.6 |

| ASC-US | 1.7 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| LSIL | 1.5 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0 |

| ASC-H | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.9 |

| HSIL | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| SCC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 |

| AGC | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Other | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Unsatisfactory | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| Total Abnormalsc | 2.4 | 3.6 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.4 |

| Subsequent Program Screening Rounds | |||||||

| Total Pap tests (n) | 11316 | 826 | 2128 | 3628 | 3194 | 949 | 581 |

| Results (%)b | |||||||

| Normal | 93.4 | 88.0 | 91.6 | 93.4 | 95.2 | 95.5 | 94.7 |

| ASC-US | 2.4 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.4 |

| LSIL | 1.1 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| ASC-H | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 |

| HSIL | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| SCC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AGC | 0.1 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Unsatisfactory | 2.3 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| Total Abnormalsc | 1.8 | 4.1 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) was implemented in four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands between 2007 and 2015: American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and the Republic of Palau. First screening round refers to a woman’s first Pap test in the NBCCEDP program, and subsequent screening rounds refer to all other Pap tests after the first screen.

ASC-US = Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; LSIL = Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; HSIL = High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; ASC-H = Atypical squamous cells, cannot rule out HSIL; SCC = Squamous cell carcinoma; AGC = Atypical glandular cells.

Includes LSIL, ASC-H, HSIL, SCC and AGC.

Screening records with “Unsatisfactory” or “Other” Pap test results were excluded from follow-up analyses; a total of 21, 872 (98.3%) cervical cancer screens had valid Pap test results and were included in analyses on follow-up and diagnostic procedures done (Table 3). A total of 515 screens had Pap or oncogenic HPV test results warranting follow-up or diagnostic procedures; 456 (2.1%) screens had abnormal low- or high-grade Pap results and 59 (0.3%) had ASC-US and HPV-positive results. Of these 515 Pap screens, colposcopy with directed-biopsy was performed for 243 (47.2%) screens, colposcopy with no biopsy was performed for 12 (2.3%) screens, ECC alone was performed for 7 (1.4%) screens, other or unspecified tests were done for 87 (16.9%) screens, and 166 (32.2%) screens had no data on diagnostic tests or follow-up done. A small number of Pap screens with normal results reported having diagnostic tests or follow-up done (0.2%, n = 37 screens), including colposcopy with directed biopsy (0.07%, n = 16 screens).

Table 3.

Description of screening and diagnostic tests provided by the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program in four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands, 2007–2015.a

| Pap Test Result | Oncogenic HPV Test or Resultb | No data on Diagnostic Tests | Colposcopy with Directed Biopsy | Colposcopy (with no biopsy) | Endocervical Curettage | Other/Test Unspecifiedd | Total (N = 21,872)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| n | % | |||||||

| Normal | No HPV Test | 19,872 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 19,900 | 90.99 |

| HPV-Positive | 55 | 5e | 0 | 0 | 2 | 62 | 0.28 | |

| HPV-Negative | 993 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 995 | 4.55 | |

| ASC-USf | No HPV Test | 313 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 336 | 1.54 |

| HPV-Positive | 17 | 33 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 59 | 0.27 | |

| HPV-Negative | 61 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 0.29 | |

| Abnormal, LSILg | No HPV Test | 106 | 104h | 6 | 4 | 46 | 266 | 1.22 |

| HPV-Positive | 2 | 10i | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0.06 | |

| HPV-Negative | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.01 | |

| Abnormal, High-gradej | No HPV Test | 37 | 89k | 3 | 1 | 36 | 166 | 0.76 |

| HPV-Positive | 1 | 6l | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.03 | |

| HPV-Negative | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | |

The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) was implemented in four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands between 2007 and 2015: American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and the Republic of Palau. Screening and subsequent diagnostic results are examined starting at the date of the Pap test until the end of the diangostic test or 6 months after end of the screening calendar year.

Oncogenic HPV testing before 2012 was conducted only to triage abnormal Pap test results. In 2012, screening guidelines changed to allow HPV test to be administered together with Pap (co-testing).

Screening records with Unsatisfactory or Other Pap test results were excluded from follow-up analyses (n = 377 records).

‘Other’ category indicates gynecologic visits made by women, but records did not specify the type of diagnostic tests or procedures done during the visit.

One additional diagnostic test, endocervical curettage, was noted for 1 record.

ASC-US = Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance.

LSIL = Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions.

One additional diagnostic test was noted for 12 records: endocervical curettage = 8; cold knife conization = 2; loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) = 2.

One additional diagnostic test was noted for 5 records: endocervical curettage = 2; cold knife conization = 1; loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) = 2.

Abnormal, High-Grade category includes high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), atypical squamous cells, cannot rule out HSIL (ASC-H), atypical glandular cells (AGC) or squamous cell carcinoma.

One additional diagnostic test was noted for 16 records: endocervical curettage = 5; cold knife conization = 5; loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) = 9.

One additional diagnostic test was noted for 5 records: endocervical curettage = 1; cold knife conization = 1; loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) = 3.

Histological outcomes of women screened are described in Table 4. There were 68 low-grade CIN, 80 high-grade CIN and 10 ICC cases detected in the 14,206 unique women screened in the period examined. The majority of low-grade CIN were detected in women younger than 50 years, with the greatest percentage detected in women aged 18–29 years (35.3%). The rates of low-grade CIN (per 1000 Pap tests) were higher in younger women aged 18–29 years, compared to other age groups. The majority of high-grade CIN were also detected in women aged 49 years or younger, with the greatest percentage detected in women aged 40–49 years (36.3%). The rates of high-grade CIN (per 1000 Pap tests) appeared to be higher in women aged 49 years or younger, compared to older women. There were no ICC cases in women aged 18–29 years and the majority of ICC cases were in women aged 40–49 years (40%). The ICC rates (per 1000 Pap tests) appeared to be higher in older women, aged 60 years and older, compared to younger women. The majority of low-grade CIN (60%), high-grade CIN (56%) and ICC (60%) were detected in the first round screens, compared to subsequent screens, and the rates per 1000 Pap tests appeared to be higher in first versus subsequent rounds. The rates of precancers or cancers detected varied each year; no apparent trend was seen in these rates between 2007 and 2015.

Table 4.

Precancers and Cancers detected in women served in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program in four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands, 2007–2015.a

| Unduplicated Women screened with Pap tests | Biopsy Confirmed Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN) and Invasive Cancer (Worst Outcome)b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| N = 14,206 | Low-grade CIN (N = 68) | High-grade CIN (N = 80) | Invasive Cervical Cancer (N = 10) | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| n | % | % | Rate/1000 Pap screens | % | Rate/1000 Pap screens | % | Rate/1000 Pap screens | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 2626 | 18.5 | 35.3 | 7.3 | 17.5 | 4.3 | 0 | 0 |

| 30–39 | 3498 | 24.6 | 27.9 | 3.8 | 27.5 | 4.5 | 10.0 | 0.2 |

| 40–49 | 4043 | 28.5 | 29.4 | 3.1 | 36.3 | 4.5 | 40.0 | 0.6 |

| 50–59 | 2862 | 20.1 | 2.9 | 0.4 | 12.5 | 2.0 | 20.0 | 0.4 |

| 60–64 | 733 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 2.9 | 20.0 | 1.5 |

| 65+ | 444 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 10.0 | 1.3 |

| Screening round with worst outcome | ||||||||

| First | 10677 | 75.2 | 60.3 | 3.8 | 56.3 | 4.2 | 60.0 | 0.6 |

| Subsequent | 3529 | 24.8 | 39.7 | 2.4 | 43.7 | 3.2 | 40.0 | 0.4 |

| Race | ||||||||

| Asian/Pacific Islanderc | 13848 | 97.5 | 98.5 | 3.1 | 97.5 | 3.6 | 100.0 | 0.5 |

| Other | 358 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Screening Year | ||||||||

| 2007 | 2617 | 18.4 | 23.5 | 5.8 | 15.0 | 4.4 | 20.0 | 0.7 |

| 2008 | 3208 | 22.6 | 14.7 | 2.5 | 18.8 | 3.7 | 20.0 | 0.5 |

| 2009 | 2341 | 16.5 | 19.1 | 3.6 | 17.5 | 3.8 | 30.0 | 0.8 |

| 2010 | 1371 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 2.7 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 10.0 | 0.4 |

| 2011 | 1038 | 7.3 | 4.4 | 1.5 | 10.0 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2012 | 697 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 2.9 | 7.5 | 4.3 | 20.0 | 1.4 |

| 2013 | 943 | 6.6 | 4.4 | 1.6 | 10.0 | 4.3 | 0 | 0 |

| 2014 | 1004 | 7.1 | 8.8 | 3.3 | 8.8 | 3.9 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015 | 987 | 6.9 | 8.8 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 |

The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) was implemented in four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands between 2007 and 2015: American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and the Republic of Palau.

Low-grade CIN = CIN1; High-grade CIN = CIN2 and CIN3.

“Asian/Pacific Islander” is a standard category for race used by NBCCEDP, and could not be further separated into “Pacific Islander” and “Asian” categories.

4. Discussion

This is the first report of cervical cancer screening and outcomes of women served by the NBCCEDP in the four US-Affiliated Pacific Islands. The 14,206 women screened for cervical cancer from 2007 to 2015 represent roughly 17.9% of all women aged 20–64 years in the four USAPI jurisdictions (Table 1); the total number of women who qualify for NBCCEDP in the four USAPIs based on limited or no-insurance and low-income requirements is unknown. The reach of the NBCCEDP in providing cervical cancer screening to women in the USAPI is partly limited by the unique technical and geographical challenges faced in this region. During the 2007–2015 period, some of the USAPI jurisdictions could not reach eligible women in their outer islands for cervical screening due to the lack of ship or airline transportation to these outer islands in some years (NBCCEDP program staff in the USAPI, personal communication, December 6, 2016). This challenge in reaching some of the USAPI outer islands may explain some of the annual variation seen in the total number of Pap and HPV tests provided by the NBCCEDP during this period.

Only two of the four USAPI grantees conducted any HPV testing (for triage or co-testing), and overall, very few HPV tests were conducted in this period. The USAPIs have to ship specimens to Hawaii or Los Angeles for Pap or HPV testing since none of the four jurisdictions currently have the capacity to process these tests on-island (NBCCEDP program staff in the USAPI, personal communication, December 6, 2016) [15]. The implementation of HPV testing in the USAPI has been slow, partly due to challenges that USAPI face in planning for high shipping and testing costs and also coordinating with the off-island laboratories to ensure timely processing and receipt of screening results.

The distribution of Pap test results by screening round in the USAPI was fairly similar to US national NBCCEDP Pap test results. The overall percentages of abnormal Pap test results in first and subsequent screening rounds were 2.4% and 1.8% for the USAPI grantees from 2007 to 2015, and these were 3.3% and 2.2%, respectively, for the national NBCCEDP data from 2003 to 2014 (NBCCEDP program staff in Atlanta, personal communication, December 15, 2016). In women aged 40 years or younger, the percentage of abnormal Pap test results in the US nationalNBC-CEDP data is observed to decrease by about half in first versus subsequent rounds [13]; however, this reduction in the percentage of abnormal Pap test results was not observed in subsequent rounds in the USAPI program data, possibly due to challenges in follow-up or treatment of precancerous lesions in women in the USAPI.

The majority of biopsy-confirmed cases detected in the USAPI were CIN2 or worse (57%); this was higher than the proportion of CIN2 or worse lesions observed in the US national NBCCEDP data (38% for the 2010–2015 period) [16]. The majority of ICC (90%) and high-grade CIN (55%) cases in the USAPI, occurred in women aged 40 years or older; however, the majority of low-grade CIN cases and abnormal Pap test results were observed in younger women. These findings are consistent with those from national NBCCEDP data and with the natural history of cervical cancer disease (NBCCEDP program staff in Atlanta, personal communication, December 15, 2016) [17]. The higher percentage of abnormal Pap test results in women aged 40 years and younger may also be due to referral of women with suspected cervical abnormalities from reproductive health clinics or programs into the NBCCEDP for cervical cancer screening and diagnosis.

We found that roughly one third (32%) of Pap screens with results warranting follow-up or diagnostic testing (results of LSIL or worse, or ASC-US with HPV-Positive results) had no data recorded on diagnostic tests or follow-up done. NBCCEDP program staff in the USAPI identified some of the reasons for the lack of data on follow-up or diagnostic tests to include: travel of women off-island for a second opinion, failure to contact women in outer islands, women not showing up for scheduled follow-up visits, and refusal of women to undergo diagnostic tests for various reasons such as fear of outcomes or the absence of female providers to conduct diagnostic tests (NBCCEDP program staff in the USAPI, personal communication, December 6, 2016). These and more challenges to following-up women screened for cervical cancer in the USAPI such as the lack of transportation for women to get to the clinics for follow-up, the fact that most women in the USAPI do not have phones, and the resistance of male partners to have their spouses examined for cervical cancer, have been discussed in the literature [11,18]. Since follow-up data was examined for each Pap screen conducted, it is possible that some tests may lack follow-up information because repeat Pap tests were conducted. However, the proportion of repeat Pap tests conducted in the US national NBCCEDP data has been previously found to be low (8.6% for ASC-US results) and would only explain a small fraction of the of Pap tests that lack information on follow-up or diagnostic testing in this analysis [19]. We also found that a small number of Pap screens with normal results reported having diagnostic tests done, including colposcopy with directed biopsy. These Pap screens need to be further investigated; they may be surveillance Pap tests for women with previously abnormal results that may have not been captured, or they may reflect the need for continued education of healthcare providers on evidence based practices and algorithms for cervical cancer screening and treatment.

The interpretation of findings on HPV testing and outcomes in this analysis may be limited by incomplete data for 2007–2008, since NBCCEDP programs were not required to comprehensively report on HPV tests and outcomes until 2009. Interpretations of outcomes by first program screening versus subsequent program screening are limited by the lack of information on women’s cervical cancer screening history and outcomes prior to entering the NBCCEDP.

5. Conclusion

In this analysis of cervical cancer screening in the USAPIs, we found that the distribution of Pap test results from the NBCCEDP’s USAPI grantees was fairly similar to that observed in US national NBCCEDP data; however, women in USAPI appeared to have a greater proportion of biopsy-confirmed high grade lesions (CIN2 or worse), compared to national NBCCEDP data. We also found that the screening programs in the USAPI had no information on follow-up or diagnostic services for roughly one-third of cases; this is likely due to geographical, technical and cultural challenges in providing diagnostic services and recording follow-up data, most of which are unique to the USAPI region. The NBCCEDP continues to work with the USAPI screening programs to thoroughly review and verify the data on women lost to follow-up after each program data submission, and examine ways to track these women for diagnostic services, and treatment initiation, if needed. The screening programs in the USAPI should further examine specific barriers to follow-up of women with abnormal Pap results and possible solutions to address them. The CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, along with partners including the Title X Family Planning program, the Maternal Child Health program and the HRSA Community Health Center Program, continue to examine resource-appropriate strategies to increase cervical cancer screening and treatment of precancerous lesions in the USAPI, taking into account the unique geographical, technical and socioeconomic challenges faced in this region [11].

The findings and conclusion of this analysis do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the program staff in the USAPI for their input in interpreting these results.

Footnotes

Author’s contributions

VS initiated and conceptualized the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. JR analyzed program data. JWM, LB, VBB and MS contributed to the interpretation of the data and revised manuscript drafts. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved it in its final form.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rural Health Information Hub. US Affiliated Pacific Basin Jurisdictions: Legal, Geographic and Demographic Information [Internet] Rural Health Information Hub: Region IX Office of the Regional Health Administrator, HHS. [cited 6 December 2016]. Available from: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/pdf/pacific_basin_chart.pdf.

- 2.Pacific Regional Central Cancer Registry. Cancer in the US Affiliated Pacific Islands 2007–2012 [Internet] Pacific Cancer Programs. 2015 [updated 2015 May; cited 6 December 2016]]. Available from: http://www.pacificcancer.org/programs/pacific-regional-central-cancer-registry.html.

- 3.Benard VB, Thomas CC, King J, Massetti GM, Doria-Rose VP, Saraiya M, et al. Vital signs: cervical cancer incidence, mortality, and screening—United States, 2007–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(44):1004–1009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palau Bureau of Public Health, Ministry of Health. National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007–2012 [Internet] Cancer Control PLANET. [updated 2006; cited 6 December 2016]. Available from: https://cancercontrolplanet.cancer.gov/state_plans/Republic_of_Palau_Cancer_Control_Plan.pdf.

- 5.Senkomago V, Cash H, Robles B, Saraiya M. Cervical Cancer Screening Prevalence in a US limited-resource setting: Results from the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands NCD Survey, 2015. Poster Presentation at HPV 2017; 2017 Feb 28–Mar 4; Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee NC, Wong FL, Jamison PM, Jones SF, Galaska L, Brady KT, et al. Implementation of the national Breast and cervical cancer early detection program: the beginning. Cancer. 2014;120(Suppl 16):2540–2548. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) Variation Across Programs. 2015 [updated 15 September 2015]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp/data/index.htm.

- 8.Moyer VA. USPSTF, Screening ffor cervical cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880–891. W312. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPTF) Screening for cervical cancer: recommendations and rationale. Am J Nurs. 2003;103(11):101–102. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, Katki HA, Kinney WK, Schiffman M, et al. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(4):829–846. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182883a34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waxman AG, Buenconsejo-Lum LE, Cremer M, Feldman S, Ault KA, Cain JM, et al. Cervical cancer screening in the United States-Affiliated pacific islands: options and opportunities. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20(1):97–104. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eheman CR, Leadbetter S, Benard VB, Blythe Ryerson A, Royalty JE, Blackman D, et al. National Breast and cervical cancer early detection program data validation project. Cancer. 2014;120(Suppl 16):2597–2603. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benard VB, Eheman CR, Lawson HW, Blackman DK, Anderson C, Helsel W, et al. Cervical screening in the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program, 1995–2001. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(3):564–571. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000115510.81613.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O’Connor D, Prey M, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2114–2119. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Townsend JS, Stormo AR, Roland KB, Buenconsejo-Lum L, White S, Saraiya M. Current cervical cancer screening knowledge, awareness, and practices among US-Affiliated Pacific Islands providers: opportunities and challenges. Oncologist. 2014;19(4):383–393. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC Cancer Division. National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), National Aggregate. Five-Year Summary: July 2010 to June 2015 [Internet] CDC Cancer Division; [updated 2016 September 9; cited 6 December 2016]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp/data/summaries/national_aggregate.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiffman M, Wentzensen N. Human papillomavirus infection and the multistage carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2013;22(4):553–560. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee opinion No. 624: cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):526–528. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000460763.59152.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watson M, Benard V, Lin L, Rockwell T, Royalty J. Provider management of equivocal cervical cancer screening results among underserved women, 2009–2011: follow-up of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(5):759–764. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0549-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]