Abstract

Objective

To assess efficacy of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for treatment of complex atypical hyperplasia or low-grade endometrial cancer.

Methods

This retrospective case series included all patients treated with the LNG-IUD for complex atypical hyperplasia or early grade endometrial cancer from January 2003 to June 2013. Response rates were calculated and association of response with clinicopathologic factors, including age, body mass index, and uterine size, were determined.

Results

Forty-six patients diagnosed with complex atypical hyperplasia or early grade endometrial cancer were treated with the LNG-IUD. Of 32 evaluable patients at the 6-month time point, 15 had complex atypical hyperplasia (47%), 9 had G1 endometrial cancer (28%), and 8 had grade 2 endometrial cancer (25%). Overall response rate was 75% (95% CI = 57 - 89) at 6 months; 80% (95% CI = 52 - 96) in complex atypical hyperplasia, 67% (95% CI = 30 - 93) in grade 1 endometrial cancer, and 75% (CI = 35 - 97) in grade 2 endometrial cancer. Of the clinico-pathologic features evaluated, there was a trend toward the association of lack of exogenous progesterone effect in the pathology specimen with nonresponse to IUD (p = 0.05). Median uterine diameter was 1.3 cm larger in women who did not respond to IUD (p = 0.04).

Conclusion

Levonorgestrel-releasing IUD therapy for the conservative treatment of complex atypical hyperplasia or early-grade endometrial cancer resulted in return to normal histology in a majority of patients.

Introduction

In 2017, there will be 61,380 new cases and 10,920 deaths from endometrial cancer(1). Among all endometrial cancers, endometrioid histology is most common (80%)(2). In general, complex atypical hyperplasia is a precursor of endometrioid endometrial cancer tumorigenesis. Indeed, 29% of untreated complex atypical hyperplasia will progress to cancer and 46% of patients with this preoperative diagnosis will have adenocarcinoma in the hysterectomy specimen(3). Surgical resection is the standard of care for both conditions(2). However, this treatment may not be ideal for women with co-morbidities precluding surgery or who have not completed childbearing(4-6). Thus, exploration of non-surgical options in this population is of interest.

Unopposed estrogen is an important risk factor for developing complex atypical hyperplasia and endometrial cancer(7). Progesterone is known to counter proliferative actions of estrogen in the endometrium. Thus, progesterone therapy has been explored as primary therapy for complex atypical hyperplasia and endometrial cancer(8). Systemic progesterone has been moderately successful, achieving response rates of 75-85% in complex atypical hyperplasia and 50-75% in endometrial cancer(9-13); however, compliance is impaired by adverse effects including vaginal bleeding, nausea, and weight gain(14). The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) has been proposed as an option for conservative treatment of complex atypical hyperplasia and endometrial cancer, although results of small studies have been mixed(15-22). Our objective was to assess efficacy of the LNG-IUD for treatment of complex atypical hyperplasia or low grade endometrial cancer. We also sought to explore the association of clinical and pathologic features with response to treatment.

Materials and Methods

After University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approval, a retrospective case series was performed to report the response rate at various time points of patients treated with the LNG-IUD for complex atypical hyperplasia or early grade endometrial cancer. Patients diagnosed with complex atypical hyperplasia , grade 1, or grade 2 endometrioid endometrial cancer treated with LNG-IUD (Mirena) therapy between January 2003 and June 2013 at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center were identified from the Institutional Tumor Registry Database and cross-referenced to a list generated using medical billing charges for IUD placement. Patients were included if they had a LNG-IUD placed for the treatment of complex atypical hyperplasia or early grade endometrial cancer. Patients were excluded if medical records were incomplete, if baseline biopsy at the time of IUD placement did not demonstrate complex atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer, or if additional systemic progesterone agents were being used to treat the hyperplasia or cancer during or after IUD placement. Reasons for IUD placement were determined including CAH, morbid obesity, multiple medical co-morbidities, desire for future fertility, or patient preference. Patient preference was defined by request for uterine-sparing treatment by a patient in absence of any of the factors mentioned above. Patients could have multiple reasons for IUD placement. Demographic, clinical, and pathologic data were collected from the electronic medical record. Specific factors of interest included age, body mass index (BMI), uterine size, prior progesterone use and metformin use. Attempts at childbearing and fertility outcomes were also collected. Prior progesterone use was defined as the use of any progesterone treatment for at least one month duration prior to LNG-IUD placement. The presence of exogenous progesterone effect, defined as attenuated glands and pseudodecidualized stroma in the pathologic specimen(23), was collected from the report for the 3- and 6-month biopsy.

In general, at our institution, patients eligible for conservative management have IUD treatment after endometrial biopsy or dilation and curettage reveals complex atypical hyperplasia or early endometrial cancer. Patients are not treated conservatively if there is metastatic disease or myometrial invasion noted on imaging with magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography. Patients are followed with endometrial biopsies every 3 months (+/- 3 months) for the first year(24). This is followed by continued surveillance every 3-6 months until progression of disease or definitive surgery as per National Comprehensive Cancer Network and European Society of Gynecologic Oncology Task Force guidelines(25). IUD is replaced in patients that continue therapy beyond 5 years. Routine imaging is not utilized during surveillance.

The primary study endpoint was response to LNG-IUD at 6 months after insertion. This time point was chosen based on existing National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommendations for conservative treatment of endometrial cancer(24). Response data were collected from the electronic medical record up to three years after LNG-IUD insertion. Complete response for complex atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer was defined as either no evidence of hyperplasia or hyperplasia without atypia on pathology report. For endometrial cancer, partial response was recorded if disease was downgraded to complex atypical hyperplasia. For endometrial cancer, stable disease was recorded if pathology revealed any remaining cancer. No response was recorded if pathologic report demonstrated no change or progressive disease. For complex atypical hyperplasia, progression was defined as the presence of any grade of cancer. For endometrial cancer, progression was defined as presence of a higher grade of cancer on biopsy. Secondary endpoints of the study included response at other time points (e.g. 3, 9, 12 months), complications, and association of clinicopathologic variables with nonresponse to LNG-IUD.

Based on existing literature, we expected a complete response rate of 80-90% in complex atypical hyperplasia and 50-60% in endometrial cancer. We calculated the proportion of patients with complete response to LNG-IUD therapy with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Under these circumstances, with 15 complex atypical hyperplasia patients, the 95% exact CI for complete response rate would have a width of 0.44. For 17 Grade 1 and 2 endometrioid patients, the 95% exact CI for complete response would have a width of 0.49. Response was defined as complete or partial response unless otherwise specified. We compared response rates by clinical and pathologic factors, including age, BMI, median uterine size, and presence of exogenous progesterone effect. We used chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests to analyze categorical data and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests to compare continuous data. A hierarchical linear model that accounted for repeated measures over time was used to compare percent of patients with initial response to therapy at each time point. Given the small sample size, there was limited power to detect anything but very large differences; therefore negative findings cannot be generalized. All the calculations were performed utilizing SPSS 21.0 (Chicago, IL) and SAS 9.3.

Results

During the study time period, 2,292 patients were seen with a new diagnosis of endometrial cancer or complex atypical hyperplasia. There were 55 patients diagnosed with either complex atypical hyperplasia or endometrioid endometrial cancer treated with the LNG-IUD. Nine patients did not meet eligibility criteria and were excluded from the analysis. The primary reason for ineligibility was placement of LNG-IUD after the patient had resolution of complex atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer from another progesterone therapy (n=6). Two patients were excluded for concurrent treatment of IUD and another progesterone therapy, one patient was excluded for incorrect pathologic diagnosis (actual diagnosis: recurrent breast cancer to endometrium). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics of included and excluded patients, including age (median 54 vs. 47 years, p=0.23), BMI (43 vs. 46 kg/m2, p=0.55), or race (white vs. nonwhite, p=0.3). Median follow-up time for all patients was 4.2 years (range 3.7 months to 12.0 years).

Among 46 eligible patients, there were no complications at the time of LNG-IUD placement or major adverse events documented in the medical record. No additional agents were utilized in combination with the LNG-IUD to treat the complex atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient population are reported in Table 1. Median BMI was 45 kg/m2 (range; 19–76) and median age was 47 years (range; 19–85). Levonorgestrel IUD treatment was continued for a median of 24 months (range; 2-94). Indications for IUD placement included the presence of multiple medical co-morbidities, morbid obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m2), desire for future childbearing potential, or patient preference. Of the 8 patients with G2 endometrioid endometrial cancer, indications included medical co-morbidities (n=1), fertility (n=1), obesity and fertility (n=3), and obesity and medical co-morbidities (n=3).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients treated with the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD for complex atypical hyperplasia or low grade endometrioid endometrial cancer*.

| Demographic / Pathologic factor | All Patients N = 46 |

Evaluable Patients N = 32 |

Non-Evaluable Patients N = 14 |

P-Value+ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | N (%) | 95% CI | N (%) | 95% CI | ||||

| Age in years (n, median, range) | N | 46 | 32 | 14 | 0.459 | |||

| Median | 47.1 | 45.6 | 53.0 | |||||

| Min-Max | 18.5 - 85.2 | 18.5 - 85.2 | 28.5 - 69.8 | |||||

| BMI in kg/m2 (n, median, range) | N | 45 | 31 | 14 | 0.961 | |||

| Median | 45 | 45 | 43.5 | |||||

| Min-Max | 19 - 74 | 20 - 74 | 19 - 70 | |||||

| Uterine Size (n, median, range) | N | 27 | 19 | 8 | 0.059 | |||

| Median | 8.9 | 8.1 | 9.7 | |||||

| Min-Max | 5.6 - 12.4 | 6.5 - 12.4 | 5.6 - 11.2 | |||||

| Race (n, %) | White | 24 (52.2%) | 36.9%-67.1 | 18 (56.3%) | 37.7%-73.6% | 6 (42.9%) | 17.7%-71.1% | 0.411 |

| Hispanic | 15 (32.6%) | 19.5%-48.0% | 10 (31.3%) | 16.1%-50.0 | 5 (35.7%) | 12.8%-64.9% | ||

| Black | 5 (10.9%) | 3.6%-23.6% | 2 (6.3%) | 0.8%-20.8% | 3 (21.4%) | 4.7%-50.8% | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (4.3%) | 0.5%-14.8% | 2 (6.3%) | 0.8%-20.8% | 0 (0.0%) | NE-23.2% | ||

| Parity (n, %) | Nulliparous | 25 (54.3%) | 39.0%-69.1% | 19 (59.4%) | 40.6%-76.3% | 6 (42.9%) | 17.7%-71.1% | 0.349 |

| Parous | 21 (45.7%) | 30.9%-61.0% | 13 (40.6%) | 23.7%-59.4% | 8 (57.1%) | 28.9%-82.3% | ||

| Histology (n, %) | CAH | 23 (50.0%) | 34.9%-65.1% | 15 (46.9%) | 29.1%-65.3% | 8 (57.1%) | 28.9%-82.3% | 0.103 |

| G1 Endometrioid | 15 (32.6%) | 19.5%-48.0% | 9 (28.1%) | 13.7%-46.7% | 6 (42.9%) | 17.7%-71.1% | ||

| G2 Endometrioid | 8 (17.4%) | 7.8%-31.4% | 8 (25.0%) | 11.5%-43.4% | 0 (0.0%) | NE-23.2% | ||

| Reason (n, %) | CAH | 3 (6.5%) | 1.4%-17.9% | 2 (6.3%) | 0.8%-20.8% | 1 (7.1%) | 0.2%-33.9% | 0.879 |

| Obesity | 3 (6.5%) | 1.4%-17.9% | 3 (9.4%) | 2.0%-25.0% | 0 (0.0%) | NE-23.2% | ||

| Comorbidity | 4 (8.7%) | 2.4%-20.8% | 2 (6.3%) | 0.8%-20.8% | 2 (14.3%) | 1.8%-42.8% | ||

| Obesity + Comorbidity | 20 (43.5%) | 28.9%-58.9% | 13 (40.6%) | 23.7%-59.4% | 7 (50.0%) | 23.0%-77.0% | ||

| Fertility | 9 (19.6%) | 9.4%-33.9% | 6 (18.8%) | 7.2%-36.4% | 3 (21.4%) | 4.7%-50.8% | ||

| Obesity + Fertility | 6 (13.0%) | 4.9%-26.3% | 5 (15.6%) | 5.3%-32.8% | 1 (7.1%) | 0.2%-33.9% | ||

| Patient Desire | 1 (2.2%) | 0.1%-11.5% | 1 (3.1%) | 0.1%-16.2% | 0 (0.0%) | NE-23.2% |

Abbreviations: IUD, intrauterine device; CAH, complex atypical hyperplasia; BMI, body mass index;

Mann-Whitney test for age, BMI and uterine size; Fisher's exact test for remaining variables; Tested distribution of variables between evaluable and non-evaluable participants

Among the 15 patients whose reason for conservative therapy included fertility, only 5 (33%) attempted pregnancy. One woman achieved successful pregnancy and live birth after conservative treatment of endometrial cancer the LNG-IUD.

Of 46 eligible patients, 32 had biopsy results at the 6-month time point and were evaluable for the primary endpoint. Of these patients, 15 (47%) had complex atypical hyperplasia, 9 (28%) grade 1 endometrial cancer and 8 (25%) grade 2 endometrial cancer. Table 2 demonstrates overall and histology-stratified response rates with 95% CI at the 6-month time point. Three patients had progression of disease. The first patient had complex atypical hyperplasia which was stable at 6 months but demonstrated grade 1 endometrial cancer at 9 months. Ultimately, she had complete resolution of disease at 15 months with the LNG-IUD. The second patient had a long history of complex atypical hyperplasia and grade 1 endometrial cancer, initially treated with Depo-Provera for one year. She had progression of grade 1 endometrial cancer to grade 2 endometrial cancer after 3 months of LNG-IUD therapy. Preoperative imaging was negative and hysterectomy specimen was negative for residual cancer. The third patient was treated with the LNG-IUD for grade 1 endometrial cancer with stable disease for 43 months with ultimate progression to grade 2 endometrial cancer. No imaging was obtained in the preoperative setting due to her BMI of 74 precluding performance of MRI or CT. Hysterectomy specimen demonstrated grade 2 endometrioid endometrial cancer with 7 out of 13 mm invasion. She was treated with vaginal cuff brachytherapy. She is now 5 years free of disease.

Table 2. Response Rates to the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD at the 6-month time point*.

| 6 Month (N=32) |

Number of responders (%) |

95% CI | CR Freq (%) |

95% CI | PR Freq (%) |

95% CI | SD Freq (%) |

95% CI | PD Freq (%) |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All N=32 |

24 (75) |

56.6 - 88.5 | 16 (50.0) |

31.9-68.1 | 8 (25.0) |

11.5-43.4 | 5 (15.6) |

5.3-32.8 | 3 (9.4) |

2.0-25.0 |

| CAH n=15 |

12 (80) |

51.9 - 95.7 | 11 (73.3) |

44.9-92.2 | 1 (6.7) |

0.2-31.9 | 2 (13.3) |

1.7-40.5 | 1 (6.7) |

0.2-31.9 |

| G1EEC n=9 |

6 (67) |

29.9 - 92.5 | 2 (22.2) |

2.8-60.0 | 4 (44.4) |

13.7-78.8 | 1 (11.1) |

0.3-48.2 | 2 (22.2) |

2.8-60.0 |

| G2EEC n=8 |

6 (75) |

34.9 - 96.8 | 3 (37.5) |

8.5-75.5 | 3 (37.5) |

8.5-75.5 | 2 (25.0) |

3.2-65.1 | 0 (0.0) |

NE-36.9 |

Abbreviations: IUD, intrauterine device; CI, confidence interval; CAH, complex atypical hyperplasia; G1EEC, grade 1 endometrioid endometrial cancer; G2EEC, grade 2 endometrioid endometrial cancer; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; Freq, frequency

Demographics and diagnoses for the 14 patients ineligible for the primary endpoint due to lack of 6 month biopsy can be found in Table 1. One patient had a hysterectomy after two months due to preference with complete response. Two patients only had biopsy at 3 months prior to loss of follow up, with a patient with grade 1 endometrial cancer demonstrating stable disease and a patient with complex atypical hyperplasia demonstrating complete response. The remaining 11 patients had pathology available from a later biopsy time point of 9 to 12 months. Complete responses were observed in 9 of patients by the later time point (5 complex atypical hyperplasia, 4 endometrial cancer). Stable disease was noted in 2 of patients by the later time point (1 complex atypical hyperplasia, one endometrial cancer). When these 14 patients are included in calculation of response rate to therapy, there are minimal changes to the results reported for the 6 month timepoint. Specifically, the overall response rate for the study is 76% (35/46). Response rate for complex atypical hyperplasia is 82% (18/22) and response rate for grade 1 endometrial cancer is 69% (11/16).

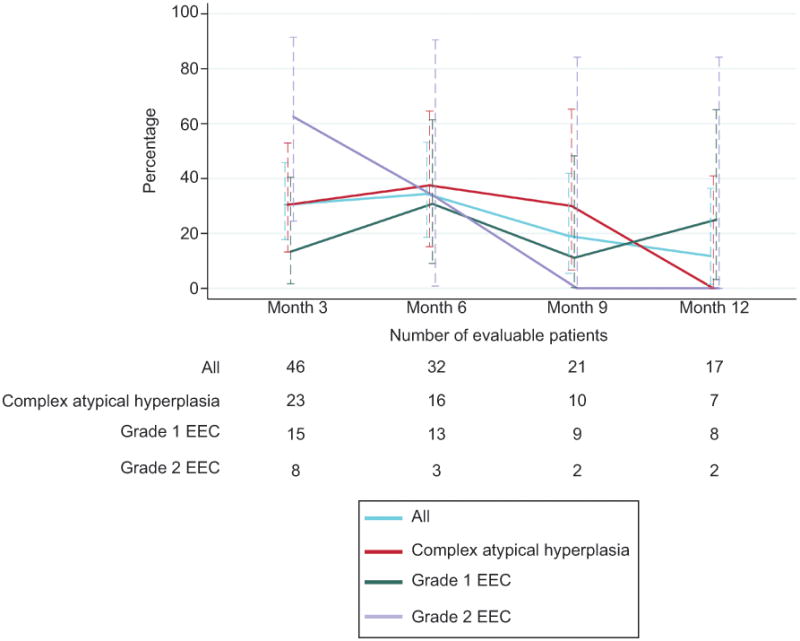

To observe the trend in initial response over time, we explored proportion of new response at each 3-month time point. Figure 1 demonstrates the comparison of histology-stratified “new” response rates at each time point. The highest response rates were found at the 3- and 6-month time points.

Figure 1.

Percentage of new responders to levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device at each time point among the entire cohort and stratified by histology. EEC, endometrioid endometrial cancer

Table 3 demonstrates the association of response at 6 months with various clinical factors. Non-responders had larger uterine size based on maximum uterine diameter (9.3 vs. 8 cm; p=0.04). However, there was no difference in response based on BMI, age, parity, and race. There was a trend toward a higher proportion of nonresponders with lack of exogenous progesterone effect (25% vs. 0%, p=0.05). Further, all responders with evaluable pathology were found to have some amount of exogenous progesterone effect at 3 or 6 months. Thirteen patients (41%) were treated with progesterone (median duration 8 months, range 1 – 48) before LNG-IUD placement and there was no association between prior therapy and response (p=0.99). Further, concurrent metformin usage (29.2% in responders and 37.5% in non-responders) was not associated with response (p=0.68).

Table 3. Association of clinical and pathologic factors and response to the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD at 6 months*.

| Variable | Responders (n=24) | 95% CI | Non-responders (n=8) | 95% CI | p-value+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (median, range) | 44.7 (18.5 – 85.2) | 48.6 (26.9 – 66.5) | 0.54 | ||

| BMI kg/m2, (median, range) | 45 (20 – 76.2) | 40 (37 - 74) | 0.95 | ||

| Uterine size, (median, range) | 8.0 (6.5 – 9.8) | 9.3 (7.6 – 12.4) | 0.04 | ||

| Uterine size | |||||

| < 9 cm | 12 (50) | 29.1-70.9 | 2 (25) | 3.2-65.1 | 0.18 |

| ≥ 9 cm | 2 (8.3) | 1.0-27.0 | 3 (37.5) | 8.5-75.5 | |

| Unknown | 10 (41.7) | 22.1-63.4 | 3 (37.5) | 8.5-75.5 | |

| Race (n, %) | |||||

| Other than whites | 12 (50) | 29.1-70.9 | 2 (25.0) | 3.2-65.1 | 0.41 |

| Whites | 12 (50) | 29.1-70.9 | 6 (75.0) | 34.9-96.8 | |

| Parity (n, %) | |||||

| Nulliparous | 15 (62.5) | 40.6-81.2 | 4 (50) | 15.7-84.3 | 0.68 |

| Parous | 9 (37.5) | 18.8-59.4 | 4 (50) | 15.7-84.3 | |

| Prior Hormone use (n, %) | |||||

| No prior progesterone | 9 (37.5) | 18.8-59.4 | 3 (37.5) | 8.5-75.5 | 0.99 |

| Prior progesterone | 10 (41.7) | 22.1-63.4 | 3 (37.5) | 8.5-75.5 | |

| Unknown | 5 (20.8) | 7.1-42.2 | 2 (25) | 3.2-65.1 | |

| Exogenous progesterone effect (n, %) | |||||

| No or minimum effect | 0 | NE-14.2 | 2 (25) | 3.2-65.1 | 0.05 |

| Marked or significant effect | 20 (83.3) | 62.6-95.3 | 4 (50) | 15.7-84.3 | |

| Unknown effect | 4 (16.7) | 4.7-37.4 | 2 (25) | 3.2-65.1 | |

| Metformin usage (n, %) | |||||

| No Concurrent Metformin | 17 (70.8) | 48.9-87.4 | 5 (62.5) | 24.5-91.5 | 0.68 |

| Concurrent Metformin | 7 (29.2) | 12.6-51.1 | 3 (37.5) | 8.5-75.5 | |

| CAH/EEC limited to polyp | |||||

| Yes | 3 (12.5) | 2.7-32.4 | 1 (12.5) | 0.3-52.7 | 0.99 |

| No | 21 (87.5) | 67.6-97.3 | 7 (87.5) | 47.3-99.7 |

Abbreviations: IUD, intrauterine device; CAH, complex atypical hyperplasia; EEC, endometrioid endometrial cancer; BMI, body mass index;

Mann-Whitney test for age, BMI and uterine size; Fisher's exact test for remaining variables, statistically significant values are bolded.

Discussion

Overall, the LNG-IUD achieved a response rate of 75% in patients with complex atypical hyperplasia and early grade endometrioid endometrial cancer. We observed high response rates in patients with grade 1 (67%) and grade 2 endometrioid endometrial cancer (75%), despite a high proportion of patients with prior progesterone treatment. Our findings must be taken carefully, as higher than expected response rates may be related to careful selection of patients for conservative therapy or due to bias inherent to retrospective studies. There were no major complications or adverse effects from LNG-IUD therapy associated with suspension or non-compliance to treatment. Indeed, patients continued the LNG-IUD treatment for a median of 23 months, demonstrating high tolerability and compliance to this modality.

Systemic progesterone therapy is an accepted conservative treatment modality for complex atypical hyperplasia and low grade endometrial cancer. Our findings in patients with complex atypical hyperplasia are in line with other studies of the LNG-IUD (10,11). The response rates of endometrial cancer to the LNG-IUD in our study are consistent with response rates reported for oral progestins, which range from 60%-80% in the literature(9, 10, 12). The low number of patients with progressive disease (n=3) during the study is intriguing. In contrast, a phase II study of the LNG-IUD in combination with a GnRH agonist and a phase II study of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate achieved response rates of 57.1% (8 of 14) and 55% (15 of 28), respectively, among endometrial cancer patients(11, 15).

Identification of non-response to LNG-IUD early in the treatment course has potential for clinical utility. We hypothesized high BMI or large uterine size might be associated with less effective local progesterone therapy. Interestingly, we found increased uterine size was associated with non-response to LNG-IUD therapy. This may be related to suboptimal placement in the uterine cavity or inadequate progesterone dosage in the enlarged uterus, allowing for reservoirs of resistant tissue. This has not been reported in the literature and should explored. Conversely, there was no significant association of elevated BMI and lack of therapy response. This may be secondary to the high overall median BMI in our population, low numbers reported in this study, or our low number of non-responders. However, these findings mirror the report by Gonthier and colleagues which noted no difference in response or recurrence rates between obese and non obese patients after fertility sparing management of complex atypical hyperplasia and endometrial cancer (13).

In our study, prior progesterone therapy did not appear to impact response to LNG-IUD therapy. The transition of patients previously treated with oral progesterone to the LNG-IUD may be an option when patients are unwilling or unable to undergo definitive surgical therapy. This finding has not been reported in the literature and will be studied further in our ongoing prospective trial of the LNG-IUD for primary treatment of patients with early endometrial neoplasia (NCT02397083).

Use of pathologic factors at interval biopsy has potential to predict response at an earlier time point. In our study, we found a trend toward association between exogenous progesterone effect and non-response at 6 months. This is in line with preliminary findings of our completed prospective study of the LNG-IUD (NCT00788671), which demonstrated an association between absence of exogenous progesterone effect at 3 months and non-response 12 months(26).

External validity of the study is strong, as there was real world variability in management. The limitations of this study are those inherent to retrospective analysis. Due to the small number of patients in the study, there exists the possibility of understating or overstating results. In addition, our study is subject to selection bias. Although the overall number of subjects reported in this study was small, this report remains one of the largest studies of the LNG-IUD in early endometrial neoplasia, especially among patients with grade 2 endometrioid histology. Further, the study is strengthened by review of all pathology results by a gynecologic pathologist.

Optimal management of patients with complex atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer who desire future fertility is unknown. In the current cohort, few patients attempted pregnancy after completion of treatment. At our center, we treat patients with progesterone until endometrial biopsy is negative for one year. IUD is removed when the patient is ready to attempt pregnancy. At completion of child-bearing, the patient is followed as any patient in surveillance for endometrial cancer, focusing on symptoms that may indicate recurrence. Decision for performance of post-childbearing hysterectomy is left to discussion between physician and patient.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH K12CA088084 K12, Calabresi Scholar Award; NIH 2P50CA098258-06, SPORE in Uterine Cancer; NIH P30CA016672, MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant; and the Andrew Sabin Family Fellowship.

Larissa A. Meyer received research funding for an unrelated work from Astra Zeneca; a grant (K07 CA201013-01) from the National Institutes of Health; a training grant from the Cancer Prevention Institute of Texas-CERCIT Scholar RP140020-C2; and personal fees from Clovis Oncology for serving as a one-time consultant on the advisory board.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017 Jan;67(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amant F, Moerman P, Neven P, Timmerman D, Van Limbergen E, Vergote I. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2005 Aug 6-12;366(9484):491–505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaino RJ, Kauderer J, Trimble CL, Silverberg SG, Curtin JP, Lim PC, et al. Reproducibility of the diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2006 Feb 15;106(4):804–11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soliman PT, Oh JC, Schmeler KM, Sun CC, Slomovitz BM, Gershenson DM, et al. Risk factors for young premenopausal women with endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Mar;105(3):575–80. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000154151.14516.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaaks R, Lukanova A, Kurzer MS. Obesity, endogenous hormones, and endometrial cancer risk: a synthetic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002 Dec;11(12):1531–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soisson AP, Soper JT, Berchuck A, Dodge R, Clarke-Pearson D. Radical hysterectomy in obese women. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Dec;80(6):940–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiderpass E, Adami HO, Baron JA, Magnusson C, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, et al. Risk of endometrial cancer following estrogen replacement with and without progestins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Jul 07;91(13):1131–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.13.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JJ, Chapman-Davis E. Role of progesterone in endometrial cancer. Semin Reprod Med. 2010 Jan;28(1):81–90. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Bodurka DC, Sun CC, Levenback C. Hormonal therapy for the management of grade 1 endometrial adenocarcinoma: a literature review. Gynecologic oncology. 2004 Oct;95(1):133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunderson CC, Fader AN, Carson KA, Bristow RE. Oncologic and reproductive outcomes with progestin therapy in women with endometrial hyperplasia and grade 1 adenocarcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2012 May;125(2):477–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ushijima K, Yahata H, Yoshikawa H, Konishi I, Yasugi T, Saito T, et al. Multicenter phase II study of fertility-sparing treatment with medroxyprogesterone acetate for endometrial carcinoma and atypical hyperplasia in young women. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Jul 01;25(19):2798–803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shan BE, Ren YL, Sun JM, Tu XY, Jiang ZX, Ju XZ, et al. A prospective study of fertility-sparing treatment with megestrol acetate following hysteroscopic curettage for well-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma and atypical hyperplasia in young women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013 Nov;288(5):1115–23. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2826-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonthier C, Walker F, Luton D, Yazbeck C, Madelenat P, Koskas M. Impact of obesity on the results of fertility-sparing management for atypical hyperplasia and grade 1 endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 Apr;133(1):33–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thigpen JT, Brady MF, Alvarez RD, Adelson MD, Homesley HD, Manetta A, et al. Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma: a dose-response study by the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1999 Jun;17(6):1736–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.6.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minig L, Franchi D, Boveri S, Casadio C, Bocciolone L, Sideri M. Progestin intrauterine device and GnRH analogue for uterus-sparing treatment of endometrial precancers and well-differentiated early endometrial carcinoma in young women. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2011 Mar;22(3):643–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giannopoulos T, Butler-Manuel S, Tailor A. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) as a therapy for endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):762–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahamondes L, Ribeiro-Huguet P, de Andrade KC, Leon-Martins O, Petta CA. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) as a therapy for endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003 Jun;82(6):580–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vereide AB, Kaino T, Sager G, Arnes M, Orbo A. Effect of levonorgestrel IUD and oral medroxyprogesterone acetate on glandular and stromal progesterone receptors (PRA and PRB), and estrogen receptors (ER-alpha and ER-beta) in human endometrial hyperplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006 May;101(2):214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wildemeersch D, Janssens D, Pylyser K, De Wever N, Verbeeck G, Dhont M, et al. Management of patients with non-atypical and atypical endometrial hyperplasia with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: long-term follow-up. Maturitas. 2007 Jun 20;57(2):210–3. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker WD, Pierce SR, Mills AM, Gehrig PA, Duska LR. Nonoperative management of atypical endometrial hyperplasia and grade 1 endometrial cancer with the levonorgestrel intrauterine device in medically ill post-menopausal women. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Jul;146(1):34–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orbo A, Vereide A, Arnes M, Pettersen I, Straume B. Levonorgestrel-impregnated intrauterine device as treatment for endometrial hyperplasia: a national multicentre randomised trial. BJOG. 2014 Mar;121(4):477–86. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laurelli G, Di Vagno G, Scaffa C, Losito S, Del Giudice M, Greggi S. Conservative treatment of early endometrial cancer: preliminary results of a pilot study. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Jan;120(1):43–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cotran RS, Kumar V, Fausto N, Robbins SL, Abbas AK. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Uterine Neoplasms. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. [cited 2017 April 25];Version 2.2017:[National Comprehensive Cancer Network] 2017 doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2023.0006. Available from: NCCN.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Rodolakis A, Biliatis I, Morice P, Reed N, Mangler M, Kesic V, et al. European Society of Gynecological Oncology Task Force for Fertility Preservation: Clinical Recommendations for Fertility-Sparing Management in Young Endometrial Cancer Patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015 Sep;25(7):1258–65. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore K, Stone R, Walter A. Society of Gynecologic Oncology 2016 Annual Meeting: Highlights and context. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Jun;141(3):416–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.04.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]