Abstract

Background

Hospital-based violence intervention programs (HVIP) aim to reduce violent-injury recidivism by providing intensive, case management services to high-risk patients who were violently injured. Although HVIP have been found effective at reducing recidivism, few studies have sought to identity how long their effects last. Additionally, prior studies have been limited by the fact that HVIP typically rely on self-report or data within their own healthcare system to identify new injuries. Our aim was to quantify the long-term recidivism rate of participants in an HVIP program using more objective and comprehensive data from a regional health information exchange (HIE).

Methods

The study included 328 patients enrolled in Prescription for Hope (RxH), an HVIP, between January 2009 and August 2016. We obtained RxH participants’ emergency department (ED) encounter data from a regional HIE database from the date of hospital discharge to February 2017. Our primary outcome was violent-injury recidivism rate of the RxH program. We also examined reasons for ED visits that were unrelated to violent injury.

Results

We calculated a 4.4% recidivism rate based on 8 years of statewide data, containing 1,575 unique encounters. Over 96% of participants were matched in the state database. Of the 15 patients who recidivated, only 5 were admitted for their injury. Over half of new violence-related injuries were treated outside of the HVIP-affiliated trauma center. The most common reasons for ED visits were pain (718 encounters), followed by suspected complications or needing additional postoperative care (181 encounters). Substance abuse, unintentional injuries, and suicidal ideation were also frequent reasons for ED visits.

Conclusion

The low, long-term recidivism rate for RxH indicates that HVIP have enduring positive effects on the majority of participants. Our results suggest HVIP may further benefit patients by partnering with organizations that work to prevent suicide, substance use disorders, and other unintentional injuries.

Level of Evidence

Therapeutic study, level III.

Keywords: Violence prevention, Hospital-based violence intervention, injury recidivism

BACKGROUND

Although there has been a downward trend in crime over the past two decades, violence-related injuries are a growing concern for many urban areas in the U.S. The number of homicides in the 50 largest U.S. cities increased by 17% from 2014 to 2015 and nearly 1.5 million patients were treated for nonfatal assaults in 2014 at U.S. emergency departments.1 In addition to human costs, such as health disparities and excess mortality, violent injury also results in high financial costs to society. The average cost of medical care for treating a patient hospitalized for violent injury has been estimated to be approximately $25,000.2 When accounting for indirect costs of injury, such as lost productivity and disability, the price is significantly greater with national estimates exceeding $30 billion annually.2 Finally, in addition to physical wounds, the effects of violent injury can result in long-term mental and physical health conditions and a decrease in quality of life.3

Hospital-based violence intervention programs (HVIP) aim to reduce both retaliatory injury and recidivism by providing intensive, case management services to high risk patients who were violently injured.4 Violently injured patients often face numerous obstacles after being discharged from the hospital including: accessing follow-up care, finding safe and adequate housing, returning to work or school, addressing legal issues, and managing posttraumatic stress and community pressure to retaliate.5 These obstacles can lead patients to continue to engage in behaviors that increase risk for re-injury, such as substance use, weapon carrying, or illegal activities.6 Violent injury recidivism has been estimated to be as high as 44% in the 5 years subsequent to an assault resulting in hospitalization.7 Young adults who are seriously injured in an assault are nearly twice as likely to have another violent injury requiring hospital treatment within two years compared to their counterparts with non-violent injuries.8 HVIP operate from the premise that there is a unique window of opportunity to effectively engage with victims of violent injury while they are recovering in the hospital.4 These programs often provide a broad range of services including medical, psychological, legal, and financial counseling in order to reduce criminal involvement and re-injury.5,9–12

Although published studies demonstrate that HVIP are effective, to date, few studies have been undertaken to identity which components of HVIP contribute to recidivism reduction and how long their effects last.5 Additionally, prior studies have been limited by the fact that HVIP typically rely on self-report or data within their own healthcare system to identify new injuries. Our study aims to improve upon previous work by measuring recidivism over an 8 year period and identifying injuries that are treated outside the HVIP-affiliated trauma center. Using data from the one of largest regional health information exchanges in the world, our study addresses limitations of prior studies by evaluating data that contains emergency department encounters for nearly the entire state.13,14 Additionally, using this resource we are able assess participants’ recidivism since the inception of the HVIP program, Prescription for Hope (RxH), over 8 years ago.

The objective of this study was to quantify the long-term recidivism rate of participants in an HVIP program using data from a regional health exchange. We hypothesized that some HVIP participants would be treated for new violent injuries outside of the original trauma center they were initially treated at. We chose to examine this because patients in urban areas have many providers that can treat their injuries and the provider they receive care from could depend on the location they are injured, how severe the injury is, and who transports them. The results of this study can provide evidence for the effectiveness of HVIP over time and may offer insight into other medical needs violently-injured patients have after trauma center discharge.

METHODS

Setting

Study participants were treated at Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Hospital, which is located in Indianapolis, IN and affiliated with Indiana University School of Medicine. The Smith Level I Shock Trauma Center at Eskenazi Hospital treats approximately 1,200 patients annually and is verified as a Level I Trauma Center by the American College of Surgeons. Eskenazi Hospital is an urban, public hospital that treats adolescent and adult trauma patients. Eskenazi Health Prescription for Hope (RxH) is a hospital-based violence intervention program focused on reducing the threat of violent injury and criminal activity in the community. RxH was established in 2009 and previous studies have been published which demonstrate its effectiveness of reducing injury recidivism.15 Currently, the program employs 4 violence intervention specialists, 2 social workers, a victims’ advocate, and a program director. RxH provides wraparound services and sets four primary goals for participants: 1) Enroll in a health insurance plan, 2) Identify a primary care provider, 3) Obtain full-time employment or return to school, and 4) Resolve any legal issues. The program also supports housing and transportation needs for participants as well as helps them navigate individual occupational, legal, and healthcare issues.

Study Population

Patients who enrolled in RxH between January 2009 and August 2016 were included in the study. In order to enroll in the program, patients must have been admitted to the trauma center for treatment of injuries that were inflicted by another person and resulted from assault, a firearm, or stabbing. Patients with self-inflicted injuries, injuries that resulted from domestic violence, or sexual assault were excluded. From 2009–2010 RxH enrolled patients 18 and older, however, this was changed in 2011 and now the program only enrolls patients ages15–30.

Follow-up Data

We obtained data on RxH participants’ emergency department (ED) encounters from the Regenstrief Institute’s Indiana Network for Patient Care (INPC) database. The INPC is a large regional health information exchange with more than 17 million unique patients over 30 years with both clinical data (e.g. provider notes, labs), as well as billing data.13 We extracted all ED records contained in the INPC for RxH patients from the date they were discharged from the hospital for their index injury through February 2017. Encounters were flagged as being potentially related to a new injury based on listed diagnosis codes and the specified reason for patients’ visits. (Table 1) We then compiled a list of unique encounter IDs that were flagged for additional review. Using these encounter IDs, all provider notes (e.g., ED progress, admission, radiology, operative, and discharge notes) associated with that encounter were reviewed. The flagged encounters were then coded as a new violent injury, a pre-existing violent injury, not a violence-related injury, or not enough information.

Table 1.

ED Diagnosis Codes for Flagged Encounters

| 379.92 | Swelling or mass of eye | 910 | Abrasion head | S31.109D | Unspecified open wound of abdominal wall, unspecified quadrant without penetration into peritoneal cavity, subsequent encounter |

| 719.47 | Pain in Joint Involving Ankle and Foot | 911 | Abrasion or Friction Burn of Trunk, without Mention of Infection | S39.81XD | Other specified injuries of abdomen, subsequent encounter |

| 723.1 | Cervicalgia | 913 | Abrasion or Friction Burn of Elbow, Forearm, and Wrist, without Mention of Infection | S50.311A | Abrasion of right elbow, initial encounter |

| 724.5 | Backache, unspecified | 916 | Abrasion or Friction Burn of Hip, Thigh, Leg, and Ankle, without Mention of Infection | S50.811A | Abrasion of right forearm, initial encounter |

| 729.5 | Pain in Limb | 918.1 | Superficial Injury of Cornea | S50.812A | Abrasion of left forearm, initial encounter |

| 729.81 | Swelling of Limb | 919 | Abrasion or Friction Burn of Other, Multiple, and Unspecified Sites, without Mention of Infection | S60.031A | Contusion of right middle finger without damage to nail, initial encounter |

| 784 | Headache | 920 | Contusion face/scalp/nck | S60.211A | Contusion of right wrist, initial encounter |

| 784.92 | Jaw pain | 921.9 | Contusion of eye nos | S60.212A | Contusion of left wrist, initial encounter |

| 786.5 | Unspecified chest pain | 922.1 | Contusion of chest wall | S60.811A | Abrasion of right wrist, initial encounter |

| 789.04 | Abdominal pain, left lower quadrant | 924.8 | Multiple contusions nec | S61.212A | Laceration without foreign body of right middle finger without damage to nail, initial encounter |

| 789.09 | Abdominal pain, other specified site; multiple sites | 924.9 | Contusion of Unspecified Site | S61.215A | Laceration without foreign body of left ring finger without damage to nail, initial encounter |

| 801.01 | Cl base fx s inj - s loc | 958.3 | Posttraum wnd infec nec | S61.237A | Puncture wound without foreign body of left little finger without damage to nail, initial encounter |

| 802 | Nasal bones, closed fracture | 959.01 | Head injury, unspecified | S61.402A | Unspecified open wound of left hand, initial encounter |

| 807 | Closed Fracture of Rib(s), Unspecified | 959.11 | Other Injury of Chest Wall | S61.411A | Laceration without foreign body of right hand, initial encounter |

| 807.01 | Closed Fracture of One Rib | 959.12 | Other injury of abdomen | S61.501A | Unspecified open wound of right wrist, initial encounter |

| 807.09 | Closed Fracture of Multiple Ribs, Unspecified | 959.19 | Other injury other sites trunk | S62.232A | Other displaced fracture of base of first metacarpal bone, left hand, initial encounter for closed fracture |

| 808.41 | Fracture of ilium-closed | 959.3 | Other and Unspecified Injury to Elbow, Forearm, and Wrist | S70.311A | Abrasion, right thigh, initial encounter |

| 810 | Closed Fracture of Clavicle, Unspecified Part | 959.4 | Hand injury nos | S71.101D | Unspecified open wound, right thigh, subsequent encounter |

| 810.03 | Closed Fracture of Acromial End of Clavicle | 959.7 | Other and Unspecified Injury to Knee, Leg, Ankle, and Foot | S71.111A | Laceration without foreign body, right thigh, initial encounter |

| 813.52 | Fx distal radius nec-opn | 995.8 | Adult maltreatment, unspecified | S72.452S | Displaced supracondylar fracture without intracondylar extension of lower end of left femur, sequela |

| 814.01 | Closed Fracture of Navicular [scaphoid] Bone of Wrist | E029.9 | Other activities | S72.91XD | Unspecified fracture of right femur, subsequent encounter for closed fracture with routine healing |

| 815 | Closed Fracture of Metacarpal Bone(s), Site Unspecified | E849.6 | Accident in public bldg | S80.01XA | Contusion of right knee, initial encounter |

| 815.01 | Closed Fracture of Base of Thumb [first] Metacarpal | E849.9 | Accidents Occurring in Unspecified Place | S80.02XA | Contusion of left knee, initial encounter |

| 815.02 | Fx metacarp base nec-cl | E916 | Struck by falling object | S80.11XA | Contusion of right lower leg, initial encounter |

| 816 | Closed Fracture of Phalanx or Phalanges of Hand, Unspecified | E917.4 | Striking Against or Struck Accidentally, by Other Stationary Object without Subsequent Fall | S80.211A | Abrasion, right knee, initial encounter |

| 816.01 | Closed Fracture of Middle or Proximal Phalanx or Phalanges of Hand | E917.9 | Other Accident Caused by Striking Against or Being Struck Accidentally by Objects or Persons with or without Subsequent Fall | S81.801D | Unspecified open wound, right lower leg, subsequent encounter |

| 816.11 | Fx mid/prx phal, hand-op | E918 | Caught Accidentally in or Between Objects | S81.802D | Unspecified open wound, left lower leg, subsequent encounter |

| 821.01 | Fx femur shaft-closed | E920.3 | Accidents Caused by Knives, Swords, and Daggers | S81.812A | Laceration without foreign body, left lower leg, initial encounter |

| 823.2 | Closed Fracture of Shaft of Tibia | E920.8 | Accidents Caused by Other Specified Cutting and Piercing Instruments or Objects | S82.252D | Displaced comminuted fracture of shaft of left tibia, subsequent encounter for closed fracture with routine healing |

| 823.92 | Fx tibia w fib nos-open | E920.9 | Acc-cutting instrum nos | S82.422D | Displaced transverse fracture of shaft of left fibula, subsequent encounter for closed fracture with routine healing |

| 824 | Fracture of Medial Malleolus, Closed | E922.9 | Firearm accident nos | S86.912A | Strain of unspecified muscle(s) and tendon(s) at lower leg level, left leg, initial encounter |

| 825 | Fracture calcaneus-close | E928.8 | Other accidents | S89.82XA | Other specified injuries of left lower leg, initial encounter |

| 825.25 | Fracture of Metatarsal Bone(s), Closed | E928.9 | Unspecified accident | S92.001D | Unspecified fracture of right calcaneus, subsequent encounter for fracture with routine healing |

| 826 | Closed Fracture of One or More Phalanges of Foot | E950.0 | Suicide-analgesics | S92.002A | Unspecified fracture of left calcaneus, initial encounter for closed fracture |

| 831 | Closed Dislocation of Shoulder, Unspecified Site | E960.0 | Unarmed fight or brawl | S92.151A | Displaced avulsion fracture (chip fracture) of right talus, initial encounter for closed fracture |

| 834 | Closed Dislocation of Finger, Unspecified Part | E965.0 | Assault by Handgun | T14.8 | Other injury of unspecified body region |

| 845 | Unspecified Site of Ankle Sprain | E965.4 | Assault-firearm nec | T74.11XA | Adult physical abuse, confirmed, initial encounter |

| 850.5 | Concussion with Loss of Consciousness of Unspecified Duration | E966 | Assault by Cutting and Piercing Instrument | T81.4XXA | Infection following a procedure, initial encounter |

| 850.9 | Concussion nos | E967.0 | Child abuse by parent | V15.51 | Personal History of Traumatic Fracture |

| 860 | Traumatic Pneumothorax without Mention of Open Wound Into Thorax | E968.0 | Assault-fire | V15.59 | Hx injury nec |

| 860.1 | Traum pneumothorax-open | E968.2 | Assault by Striking by Blunt or Thrown Object | V54.15 | Aftercare healing traumat fx u |

| 861.3 | Lung injury nos-open | E968.8 | Assault by Other Specified Means | V54.17 | Aftercare heal traumat fx vert |

| 872.01 | Open wound of auricle | E968.9 | Assault nos | V54.89 | Other orthopedic aftercare |

| 873 | Open wound of scalp | E969 | Late effect assault | V58.32 | Encounter for Removal of Sutures |

| 873.4 | Open Wound of Face, Unspecified Site, Uncomplicated | E977 | Late Effects of Injuries Due to Legal Intervention | V58.43 | Aftercare follow surg injury&t |

| 873.42 | Open wound of forehead | E985.4 | Undeter circ-firearm nec | V62.84 | Suicidal ideation |

| 873.44 | Open Wound of Jaw, Uncomplicated | E988.9 | Injury by Unspecified Means, Undetermined Whether Accidentally or Purposely Inflicted | V62.85 | Homicidal ideation |

| 873.49 | Open Wound of Face, Other and Multiple Sites, Uncomplicated | M79.5 | Residual foreign body in soft tissue | V71.4 | Observation following other accident |

| 873.5 | Open wnd face nos-compl | O9A.212 | Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes complicating pregnancy, second trimester | W20.8XXA | Other cause of strike by thrown, projected or falling object, initial encounter |

| 873.8 | Other and Unspecified Open Wound of Head without Mention of Complication | S00.12XA | Contusion of left eyelid and periocular area, initial encounter | W22.8XXA | Striking against or struck by other objects, initial encounter |

| 874.8 | Open wound of neck nec | S00.431A | Contusion of right ear, initial encounter | W29.3XXA | Contact with powered garden and outdoor hand tools and machinery, initial encounter |

| 875 | Open Wound of Chest (Wall), without Mention of Complication | S00.81XA | Abrasion of other part of head, initial encounter | W29.4XXA | Contact with nail gun, initial encounter |

| 876 | Open wound-back/s comp | S00.83XA | Contusion of other part of head, initial encounter | W34.00XA | Accidental discharge from unspecified firearms or gun, initial encounter |

| 879.2 | Open Wound of Abdominal Wall, Anterior, without Mention of Complication | S01.01XA | Laceration without foreign body of scalp, initial encounter | W34.00XD | Accidental discharge from unspecified firearms or gun, subsequent encounter |

| 879.4 | Opn wnd lateral abdomen | S01.112A | Laceration without foreign body of left eyelid and periocular area, initial encounter | W34.00XS | Accidental discharge from unspecified firearms or gun, sequela |

| 879.8 | Open wound site nos | S01.119A | Laceration without foreign body of unspecified eyelid and periocular area, initial encounter | X95.9XXD | Assault by unspecified firearm discharge, subsequent encounter |

| 879.9 | Opn wound site nos-compl | S01.81XA | Laceration without foreign body of other part of head, initial encounter | X95.9XXS | Assault by unspecified firearm discharge, sequela |

| 881 | Open Wound of Forearm, without Mention of Complication | S05.01XA | Injury of conjunctiva and corneal abrasion without foreign body, right eye, initial encounter | X99.1XXA | Assault by knife, initial encounter |

| 882 | Open Wound of Hand Except Fingers Alone, without Mention of Complication | S06.2X9A | Diffuse traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness of unspecified duration, initial encounter | X99.8XXA | Assault by other sharp object, initial encounter |

| 882.1 | Opn wound hand-complicat | S09.8XXA | Other specified injuries of head, initial encounter | Y04.0XXA | Assault by unarmed brawl or fight, initial encounter |

| 883 | Open wnd finger/s comp | S10.91XA | Abrasion of unspecified part of neck, initial encounter | Y04.1XXA | Assault by human bite, initial encounter |

| 890 | Open wound up leg/s comp | S20.211A | Contusion of right front wall of thorax, initial encounter | Y04.8XXA | Assault by other bodily force, initial encounter |

| 891.1 | Open wnd knee/leg-compl | S20.212A | Contusion of left front wall of thorax, initial encounter | Y07.04 | Female partner, perpetrator of maltreatment and neglect |

| 892 | Open Wound of Foot Except Toe(s) Alone, without Mention of Complication | S21.111D | Laceration without foreign body of right front wall of thorax without penetration into thoracic cavity, subsequent encounter | Y09 | Assault by unspecified means |

| 905.2 | Late effect arm fx | S21.112D | Laceration without foreign body of left front wall of thorax without penetration into thoracic cavity, subsequent encounter | Y35.813A | Legal intervention involving manhandling, suspect injured, initial encounter |

| 906 | Lt eff opn wnd head/trnk | S21.211A | Laceration without foreign body of right back wall of thorax without penetration into thoracic cavity, initial encounter | Y83.8 | Other surgical procedures as the cause of abnormal reaction of the patient, or of later complication, without mention of misadventure at the time of the procedure |

| 906.1 | Late Effect of Open Wound of Extremities without Mention of Tendon Injury | S24.109D | Unspecified injury at unspecified level of thoracic spinal cord, subsequent encounter | Z48.02 | Encounter for removal of sutures |

| 908.9 | Late effect injury nos | S27.9XXD | Injury of unspecified intrathoracic organ, subsequent encounter | Z87.828 | Personal history of other (healed) physical injury and trauma |

ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes associated with flagged ED encounters where a potential violence-related injury was suspected. Encounters were flagged based on both diagnosis codes and the listed reason for ED visit. We flagged all ED encounters for injury, even when intent could not be determined by the diagnosis code.

Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome of interest was long-term injury recidivism of RxH participants. Patients were considered to have recidivated if they had an ED visit for a new injury that was purposefully inflicted by another person during the follow-up period. Because ED encounters commonly use injury diagnosis codes for patients with non-acute injuries, we distinguished between old and new injuries using provider notes. ED encounters were also classified based on common reasons for visits including pain, suspected complications or need for additional postoperative care, substance use, chronic medical conditions, chronic pain, unintentional injuries, and suicidal ideation. Because each ED visit can have multiple diagnoses associated with it, categories were not mutually exclusive.

Analysis

ED visit data was analyzed descriptively and frequencies and percentages for types of encounters are presented. Participant characteristics of those who recidivated versus those who did not were compared using chi square and t tests. All tests were two sided and alpha was set a 0.05.

RESULTS

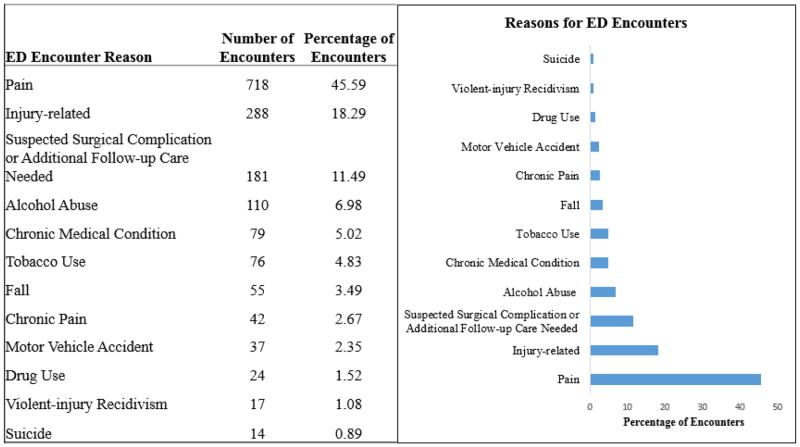

Between January 2009 and August 2016, The RxH program enrolled 328 patients. We were able to identify 317 patients (96.6%) in the INPC database. Of these 317 patients, 242 patients (76.3%) had ED visits. Patients had 1,575 unique encounters at 11 different EDs. Based on diagnosis codes and the patient’s stated reason for visit, the most common reason for being treated at the emergency department was due to pain (718 encounters). The second most common reason was due to suspected complications or the need for additional postoperative care (181 encounters). Encounters were also commonly coded for substance use (110 encounters for alcohol abuse, 76 for tobacco use, and 24 for other types of drug use). We also identified 79 encounters related to chronic medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, asthma, etc.), 42 for chronic pain, and 14 encounters for suicidal ideation. Encounters for accidental injuries were also common in this cohort, with 37 visits related to motor vehicle crashes and 55 related to falls. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. ED Encounter Types and Frequencies.

Pain was the most common reason for visiting the ED, followed by other injury-related complaints, and suspected surgical complications or additional follow-up care needed. Other co-morbid conditions were also common. “Injury-related” visits were a general category that captured conditions such as fracture, abrasions, contusions, etc. If a mechanism of injury was specified, such as a fall, then the encounter was categorized as such. Because encounters often have multiple diagnoses, these categories are not mutually exclusive. For example, a single encounter may be coded as both injury-related and alcohol abuse, if both were indicated in the ED data.

We flagged 288 encounters for additional review based on diagnosis codes and the listed reason for ED visit. There were 1,949 provider notes associated with the flagged encounters in the INPC. There were 40 encounters with no notes available, 93 with notes that did not specify what happened to the patient, and 4 notes where we could not ascertain whether an old or new violent injury was being treated. We identified 17 encounters for new violence-related injuries, which were treated at 3 different hospitals, all belonging to different health systems. Nine of these injuries were treated at the hospital associated with the RxH program, whereas 8 were treated at other institutions. A total of 15 patients recidivated (4.4%), with two participants sustaining multiple violence-related injuries during the follow-up period. Of these 17 encounters, 5 were admitted to inpatient care and 12 were discharged from the ED. Most encounters were the result of physical assault (10), however, 6 new injuries were caused by firearms and 1 was due to stabbing. None of the encounters indicated that the patient died, however, based on an obituary search, we are aware of at least one participant who is deceased.

There were no significant differences in regards to age, gender, race/ethnicity, mechanism of injury, education level, employment at time of injury, and program goal completion between those who recidivated and those who did not. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics by Recidivism Status

| Did Not Recidivate (n=313*) | Recidivated (n=15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 27.8 (10.5) | 32.5 (12.1) | 0.092 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.968 | ||

| Female | 38 (12.1) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Male | 274 (87.5) | 13 (86.7) | |

| Transgender | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.775 | ||

| White | 58 (18.5) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Black | 243 (77.6) | 11 (73.3) | |

| Hispanic | 6 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 6 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Type of Injury, n (%) | 0.860 | ||

| Assault | 45 (14.4) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Gunshot Wound | 215 (68.7) | 9 (60.0) | |

| Stab Wound | 50 (16.0) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.649 | ||

| Less Than HS | 146 (50.5) | 6 (40.0) | |

| High School Graduate/GED | 105 (36.3) | 6 (40.0) | |

| Some College or More | 38 (13.1) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Employed at Time of Injury, n (%) | 0.544 | ||

| No | 153 (56.0) | 9 (64.3) | |

| Yes | 120 (44.0) | 5 (35.7) | |

| Program Goal Completion, n (%) | 0.583 | ||

| Incomplete | 141 (46.4) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Partial Completion | 74 (24.3) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Completion | 89 (29.3) | 5 (33.3) |

This category combines 302 patients with follow-up data that did not recidivate with 11 patients who were not in the INPC database. Patients not in the database did not have any additional healthcare encounters in any setting within the region after their initial injury.

DISCUSSION

Overall our study demonstrated that the recidivism rate for RxH participants remains low compared to published U.S. data.7 Our results show that over half of new violence-related injuries were treated outside of the HVIP-affiliated trauma center, indicating that relying on single-institution data to evaluate HVIP programs may be unreliable. We also found that most new injuries were relatively minor compared to the index injury and were treated and released from the emergency department.14 In the first year of the RxH program, we reported a 2.9% 1-year recidivism rate.15 The current study found a 4.4% recidivism rate based on 8 years of statewide data, which indicates that RxH has an enduring positive effect on the vast majority of participants.

Our study also demonstrates that violently-injured patients have a variety of medical issues that are being treated in emergency departments. Pain was the most common reason for ED visits which may indicate patients are not being discharged with adequate pain medication or that they are developing chronic pain from their injuries. It is also possible that they are either misusing pain medication or selling it as a means to provide income. Finally, our data shows that patients often receive follow-up care for their injuries in an ED setting, suggesting there is a need to improve access to outpatient care after hospital discharge. This may indicate that discharge instructions regarding wound care may be unclear or symptoms of infection are not well understood by patients and caregivers. Future studies on what prompts these types of ED encounters are needed and this information could be applied to improving the discharge planning process.

Our study shows that HVIP patients are also susceptible to other types of injuries, including overdoses, suicides, motor vehicle accidents, and falls. This suggests the need to broaden the focus beyond violence-related injuries in this population. In particular, we found that patients who attempt suicide often do so beyond the typical 1 year HVIP follow-up period. Additionally, suicidal patients tend to have more ED encounters and present with other behavioral health issues.

Limitations

The primary limitation of our study was that it examined the recidivism rates from participants in a single HVIP program. Our study did not include controls since previous studies, including one on our own program, have found that HVIP successfully reduce recidivism rates. Our study aim was to examine long-term recidivism outcomes of participants and identify potential gaps in how HVIP evaluate their recidivism rates as opposed to assessing the efficacy of HVIP.

Conclusion

Based on our results and those of other studies, we conclude that HVIP, and the RxH program in particular, are effective at decreasing recidivism of violent injuries and can sustain their effects over many years. However, adequate evaluation of HVIP likely requires access to data from multiple institutions that contain detailed information on encounters in the form of provider notes. Furthermore, HVIP may benefit patients by seeking out partnerships with organizations that work to prevent suicide, substance use disorders, and other unintentional injuries.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources:

This publication was made possible with support from Grant Numbers, KL2TR001106, and UL1TR001108 (A. Shekhar, PI) from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award; The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma; and Grant Number 1R01AG052493-01A (B Zarzaur, Co-PI) from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

TMB designed the study, performed data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. DG, BAM, JM, BO, BM, RM, and CJS acquired data and made critical revisions to the manuscript. BLZ interpreted data and provided critical revisions of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Major Cities Chiefs Association. [Accessed April 21, 2017];Violent Crime Survey - Totals Comparison between 2015 and 2014. 2016 https://www.majorcitieschiefs.com/pdf/news/vc_data_20152014.pdf.

- 2.Corso PS, Mercy JA, Simon TR, Finkelstein EA, Miller TR. Medical costs and productivity losses due to interpersonal and self-directed violence in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(6):474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Potenza B, Sise M, Anderson JP. High rates of acute stress disorder impact quality-of-life outcomes in injured adolescents: mechanism and gender predict acute stress disorder risk. J Trauma. 2005;59(5):1126–1130. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196433.61423.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin-Mollard M, Becker M. [Accessed April 21, 2017];Key Components of Hospital-based Violence Intervention Programs. 2009 http://nnhvip.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/key.pdf.

- 5.Juillard C, Cooperman L, Allen I, Pirracchio R, Henderson T, Marquez R, Orellana J, Texada M, Dicker RA. A decade of hospital-based violence intervention: Benefits and shortcomings. J Trauma. 2016;81(6):1156–1161. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson JB, St Vil C, Sharpe T, Wagner M, Cooper C. Risk factors for recurrent violent injury among black men. J Surg Res. 2016;204(1):261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goins WA, Thompson J, Simpkins C. Recurrent intentional injury. J Natl Med Assoc. 1992;84(5):431–435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham RM, Carter PM, Ranney M, Zimmerman MA, Blow FC, Booth BM, Goldstick J, Walton MA. Violent reinjury and mortality among youth seeking emergency department care for assault-related injury: a 2-year prospective cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(1):63–70. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper C, Eslinger DM, Stolley PD. Hospital-based violence intervention programs work. J Trauma. 2006;61(3):534–537. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000236576.81860.8c. discussion 537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juillard C, Smith R, Anaya N, Garcia A, Kahn JG, Dicker RA. Saving lives and saving money: hospital-based violence intervention is cost-effective. J Trauma. 2015;78(2):252–257. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000527. discussion 257–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purtle J, Dicker R, Cooper C, Corbin T, Greene MB, Marks A, Creaser D, Topp D, Moreland D. Hospital-based violence intervention programs save lives and money. J Trauma. 2013;75(2):331–333. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318294f518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith R, Dobbins S, Evans A, Balhotra K, Dicker RA. Hospital-based violence intervention: risk reduction resources that are essential for success. J Trauma. 2013;74(4):976–980. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31828586c9. discussion 980–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biondich PG, Grannis SJ. The Indiana network for patient care: an integrated clinical information system informed by over thirty years of experience. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;(Suppl):S81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman E, Rising K, Wiebe DJ, Ebler DJ, Crandall ML, Delgado MK. Recurrent violent injury: magnitude, risk factors, and opportunities for intervention from a statewide analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(9):1823–1830. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez G, Simons C, St John W, Creasser D, Hackworth J, Gupta P, Joy T, Kemp H. Project Prescription for Hope (RxH): trauma surgeons and community aligned to reduce injury recidivism caused by violence. Am Surg. 2012;78(9):1000–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]