Abstract

The synthesis of polymer-based assemblies for light harvesting has been motivated by the multi-chromophore antennas that play a role in natural photosynthesis for the potential use in solar conversion technologies. This review describes a general strategy for using polymer-based chromophore–catalyst assemblies for solar-driven water oxidation at a photoanode in a dye-sensitized photoelectrochemical cell (DSPEC). This report begins with a summary of the synthetic methods and fundamental photophysical studies of light harvesting polychormophores in solution which show these materials can transport excited state energy to an acceptor where charge-separation can occur. In addition, studies describing light harvesting polychromophores containing an anchoring moiety (ionic carboxylate) for covalent bounding to wide band gap mesoporous semiconductor surfaces are summarized to understand the photophysical mechanisms of directional energy flow at the interface. Finally, the performance of polychromophore/catalyst assembly-based photoanodes capable of light-driven water splitting to oxygen and hydrogen in a DSPEC are summarized.

Keywords: Energy conversion and storage; Energy and charge transport; Ru-containing polymer system; Dye-sensitized photoelectrochemical cells; Water oxidation; Photoanode, polymeric chromophore-water oxidation

Introduction

Artificial photosynthesis mimics the natural process occurring in plants with specifically engineered light-harvesting systems to carry out the direct transformation of light energy to that stored in a chemical bond (i.e. a solar fuel) [1]. The ultimate goal in artificial photosynthesis is to generate carbon-based fuels from water splitting and CO2 reduction with sunlight as shown in Eq 1 [2].

| 1 |

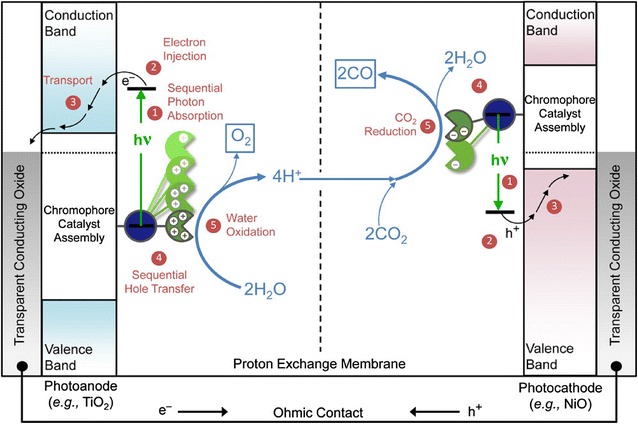

Toward this goal, artificial photosynthesis as an integrated system requires multifunctional behavior that generally consist of three parts: collection of light across a broad portion of the solar spectrum, transportation of photo excited-energy to charge separation sites of pigment (or chromophore) assemblies, and utilization of the photoexcited carriers to drive catalytic reactions that produce chemical fuel [3, 4]. Integration of multiple components to facilitate these photoelectrochemical events is necessary to achieve highly efficient solar-to-fuel conversion. In order to develop artificial photosynthesis, dye-sensitized photoelectrochemical cells (DSPECs) have been designed and investigated to provide an architecture to drive water splitting and CO2 reduction at n- and p-type semiconductor oxides with molecular-level light absorption and catalysis as shown in Fig. 1 [5, 6]. Surface-bound chromophore–catalyst assemblies at the photoanode and photocathode absorb light and perform the solar fuel half-reactions. To date DSPEC systems have integrated light harvesting assemblies utilizing a variety of architectures such as polymers, dendrimers, and peptides [7–13].

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram for a tandem DSPEC for solar-driven CO2 splitting into CO and O2 by the net reaction, 2CO2 + 4 hν → 2CO + O2

(Reproduced with permission from Ref. [5]. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society)

In natural photosynthesis, a multi-chromophore antenna system absorbs light efficiently and transmits excited-state energy rapidly to a reaction center. Related antenna strategies can be achieved with polychromophoric polymers. Ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes have been widely used over the last decades as light harvesting chromophores due to their high absorptivity in the visible spectrum for a strong metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) transition [11, 14–17]. Ruthenium(II) polypyridine complexes incorporated into a polymer scaffold offer a potential means of developing light-harvesting antenna systems for applications in dye-sensitized photovoltaic cells and artificial photosynthesis. According to previous studies, MLCT excitons in polymeric chromophore systems exhibit a site-to-site hoping mechanism along the polymer chains [18, 19]. In the past several decades there have been a number of reported polymeric chromophore systems containing pendant ruthenium(II) polypyridine as light harvesting units because of beneficial properties such as remarkable photo- and thermal stability and long-distance exciton and charge transport [20–25]. Recently, our research group has carried out investigations of the photophysical and electrochemical properties of novel polychromophores or polychromophore–catalyst assemblies in order to understand the photodynamics of charge and exciton transport in solution and at the interface of semiconductor materials [19, 26, 27].

Constructing films of defined molecular composition has been a priority of applied material and interface science. Layer-by-layer (LbL) polyelectrolyte self-assembly offers a simple and versatile tool to allow facile control of molecular assemblies prepared directly on substrate films [28]. Most LbL polyelectrolyte films feature multilayers composed of positively and negatively charged polyelectrolytes and employ the electrostatic Coulomb interaction between the oppositely charged macromolecules to form stable films. LbL technology has promising applications in solid-state light-emitting devices [29], drug delivery [30], biomembrane [31], electrodialysis membranes [32], and diagnostics [33]. Very recently, Leem et al. used the LbL approach to construct multilayers for the use in a DSPEC [26].

This review is focused on the synthesis, and photophysical properties of polymeric assemblies consisting of multiple Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes as well as the polyelectrolyte LbL chromophore–catalyst assembly deposited onto semiconductor substrates for use in a DSPEC. The review highlights light-driven water oxidation using a polymeric chromophore–catalyst assembly immobilized onto a semiconductor at a DSPEC photoanode.

Polymer-based metal complex assemblies

Synthesis and characterization of polymer-based metal complex assemblies

Our research group has been interested in developing polymerization strategies to prepare functionalized polystyrenes that feature pendant metal–organic chromophores and to investigate the photophysical and electrochemical properties of the chromophoric sites preserved in the polymer. As an early synthetic strategy, polymer assemblies containing a [tris(bipyridyl)ruthenium(II) derivatives] were considered for creating polymer assemblies that could be modified by introducing polypyridyl Ru complexes [24, 25, 34].

Polypyridyl complexes of ruthenium were attached to styrene-p-(chloromethyl) styrene copolymers derivatized via nucleophilic displacement of chloride followed by the formation of an ether (1) or ester linkage (2) in Table 1 [24]. Based on electronic absorption spectral data of ether and amide-linked polymers, the photophysical properties of the metal to ligand charge-transfer transitions of ruthenium(II) complexes on the polymeric chain are unchanged upon binding to the polymers. For an amide-linked polymer (3), the aminated poly(styrene-p-(aminomethyl)styrene) (co-PS-CH2NH2) can be coupled with a carboxylic acid derivative of the Ru metal complex in the presence of a couple of reagents [25, 34]. The amide-linked polymer strategy is a preferable coupling chemistry because of the availability of a variety of carboxylic acid derivatives of metal chromophores and quenchers. More interestingly, intra-strand energy transfer in the amide-linked polymer is known to be rapid compared to energy transfer in the ether-linked polymer due to the electron withdrawing effect of the amide link relative to the ether link.

Table 1.

Monofunctional polymers containing Ru(II) chromophoric sites

| Polymer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absmax

a

dπ − π* (nm) |

454 (1) 478 (2) |

458 | 458 | 451 | 460 | 456 |

| λem (nm) | 655 (1) 658 (2) |

646 | 645 | 623 | 640 | 657 |

| Refs | [24] | [25, 34] | [35] | [22] | [21] | [23] |

aAbsorption maximum (± 3 nm) for the most intense metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) band measured in acetonitrile solution

The polymer poly(4(2-[N,N-bis(trimethylsilyl)amino]ethyl)styrene) (4) was prepared by a living anionic polymerization method that offers well-controlled polymer chain lengths and narrow polydispersity (Mw/Mn < 1.2) compared to the previous polymer (3) that was prepared by free radical polymerization and had a PDI of 1.5 [35]. The amide coupling reaction was carried out to link a ruthenium polypyridyl complex to the amino polymer. A major drawback of this anionic polymerization is monomer functional group tolerance under the strongly basic reaction conditions. As a key advantage, however, that aids the investigations of the photophysical properties of the polymer, the amino polymers synthesized by this method are linear and optically transparent in the visible region.

Our group reported the synthesis of a polystyrene backbone by the reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization method combined with the azide-alkyne Huisgen cycloaddition as a “click chemistry” reaction [22]. The azide-alkyne click reaction affords a high yield for grafting Ru(II) complexes containing a terminal acetylene group onto the methyl azide functionalized polystyrene backbone. This is followed by the formation of a triazole linker under mild reaction conditions at room temperature. From emission quantum yield and lifetime studies, the MLCT excited state is efficiently quenched in the RAFT PS-Ru polychromophores (5) relative to a model Ru complex chromophore in the absence of a polymer backbone. Interestingly, the thiol (–SH) end-groups on the polymers from the RAFT chain transfer agent can quench the MLCT state by a charge-transfer mechanism among the chromophore, leading to considerable reduction in the lifetime of the MLCT state.

Recently, in order to eliminate the thiol polymer end-groups we developed atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) and nitroxide-mediated controlled radical polymerization (NMP) methods to prepare polystyrene-based polychromophores with pendant Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes [18, 20, 21, 23]. The ATRP method allows for postpolymerization modification by incorporating –Br end group functionality [21]. The polypyridylruthenium derivatized polystyrenes were achieved in two steps. The polystyrene backbone was prepared by ATRP of the N-hydroxyscuccinimide (NHS) derivative of 4-vinyl benzoate with methyl α-bromoisobutyrate as the initiator. Subsequently an amide coupling reaction of the NHS-polystyrene with Ru(II) complexes derivatized with aminomethyl groups ([Ru(bpy)2(CH3-bpy-CH2NH2)]2+) afforded polypyridylruthenium derivatized polystyrenes, (6).

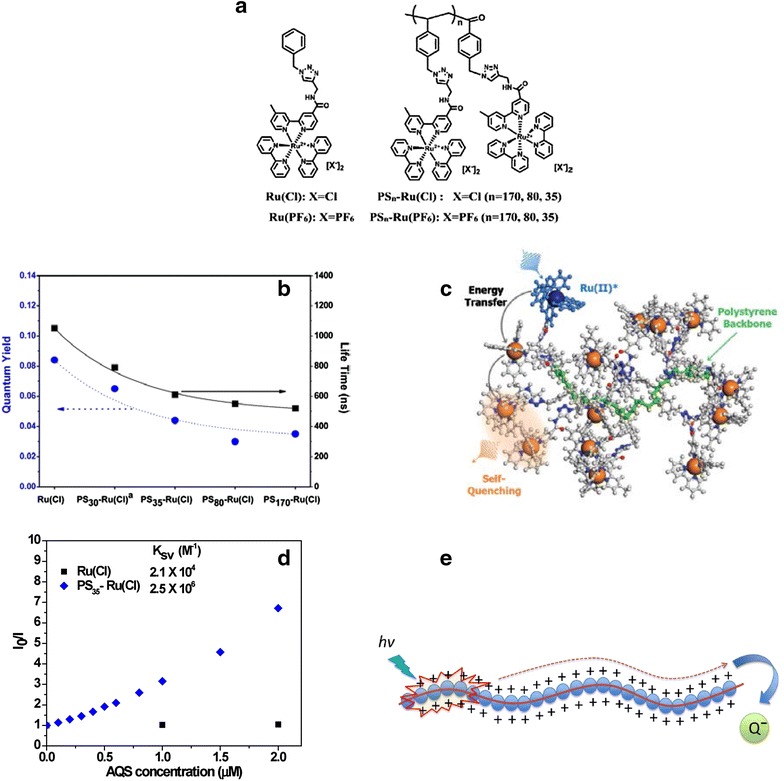

Leem et al. [23] explored systematic structure–property relationships using a series of polystyrene backbone polymers containing Ru(II) polypyridyl pendant chromophores, (7). The NMP and “click chemistry” methodology affords polymers with precisely defined number average molecular weights (Mn) ranging from ~ 5500 to 24,000 g mol−1 with a high efficiency for the click grafting of Ru chromophores to the polymer backbone. The emission quantum yield and lifetimes for the polymers in solution systematically decrease with increasing molecular weight as shown in Fig. 2. With an increased loading of Ru metal chromophores on the polymer assemblies, the probability of exciton migration from the MLCT excited states to trap sites within the close-packed Ru pendants in a polymer backbone becomes more pronounced. Exciton-exciton annihlilation also becomes important at high light flux. Importantly, we confirmed the existence of exciton hopping along the polymer chains according to emission quenching studies of the model compound, Ru(Cl) and polymers, PSn-Ru(Cl). The luminescence of the cationic Ru(Cl) and PSn-Ru(Cl) is quenched by oppositely charged sodium 9,10-anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQS). Quenching of the polymers exhibited significant amplification (~ 100-fold) in comparison to the quenching of the Ru(Cl).

Fig. 2.

a Structures of the model complex, Ru(PF6) and Ru(Cl) and ruthenium derivatized polystyrene (PSn-Ru(PF6) and PSn-Ru(Cl)). b Plot of the lifetime (black square) and quantum yield (blue circle). c Proposed energy transfer and self-quenching mechanisms. d Stern–Volmer plot (I0/I vs. [AQS]) for emission quenching of Ru(Cl), and PS35-Ru(Cl) with AQS by monitoring the emission intensity at 673 nm. e Illustration of excition quenching in the presence of quencher

(Reproduced with permission from ref [23]. Copyright 2015 the Royal Society of Chemistry)

Polymeric chromophores on metal oxide films

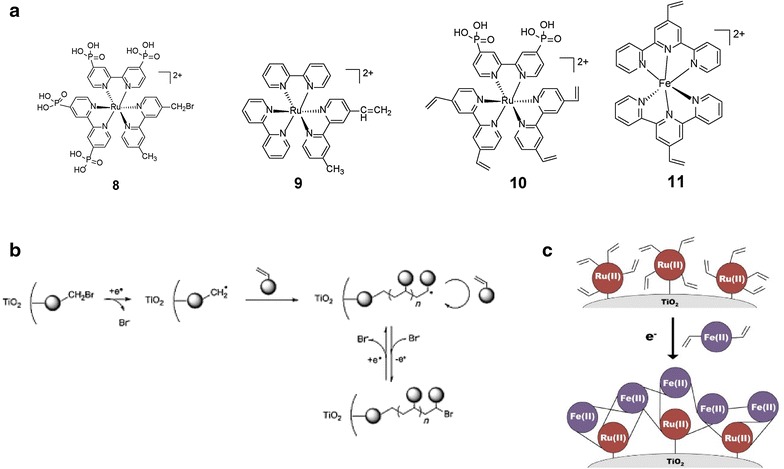

The Schanze and Meyer research groups have focused on the development of functional multi-chromophore light harvesting assemblies by coupling polymer assemblies to mesoporous semiconductor surfaces for understanding of the structure and dynamical phenomena relating to solar energy conversion systems. For example, covalently or noncovalently surface-bound polychromophoric assemblies have been used that contain anchoring group (i.e. –COOH and PO3H2) or oppositely charged chains to bind the assembly onto a mesoporous semiconductor surface for excited state electron injection into conduction band of semiconductor. As shown in Fig. 3, the initiator site, [Ru(4,4′-PO3H2-2,2′-bpy)2(4-Br-4′-Mebpy)]2+ (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine, Mebpy = 4,4′-diphosphonic acid-2,2′-bipyridine, 8 was covalently bound to the TiO2 surface. Then, the reductive initiation of [Ru(bpy)2(4-Me-4′-vinlybpy)]2+(4-Me-4′-vinylbpy = 4-vinyl-4′-methyl-2,2′-bipyridine), 9 occurs at surface bound 8 onto TiO2 nanoparticles by electrochemically controlled radical polymerization [36]. Similarly, [Ru(5,5′-divinyl-2,2′-bipyridine)2(4,4′-(PO3H2)2-bpy)]2+ containing a phosphonated bipyridine ligand as anchoring group and vinyl functionalized bipyridine ligands, 10 was selected as the monomer precursor [37]. After the immobilization of 10 as the inner molecular layer in mesoporous TiO2 film, [Fe(v-tpy)2]2+ (v-tpy = 4′-vinyl-2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine), 11 was reductively electropolymerized onto the existing surface film of 10, which resulted in enhanced photostability in comparison to the surface-bound Ru complex only. With the use of transient absorption spectroscopy of the polymer-loaded TiO2, it was shown that photoexcitation of the surface-bound Ru chromophore is followed by electron injection and FeII to RuIII electron transfer.

Fig. 3.

a Structures of [Ru(4,4′-PO3H2-2,2′-bpy)2(4-Br-4′-Mebpy)]2+ (8), [Ru(bpy)2(4-Me-4′-vinlybpy)]2+ (9), Ru(5,5′-(R)2-bpy)2Cl2 (R=CH=CH2) (10), [Fe(v-tpy)2]2+ (v-tpy = 4′-vinyl-2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine) (11). b Mechanism of the oligomeric growth of RuII complexes from 8 in the cavities of the mesoporous TiO2 film. c Schematic diagram of the surface structure following reductive polymerization of 11 on TiO2-10

(Reproduced with permission from Ref. [36, 37]. Copyright 2014, Wiley–VCH Verlag Gmbh & Co. and 2013, American Chemical Society, respectively)

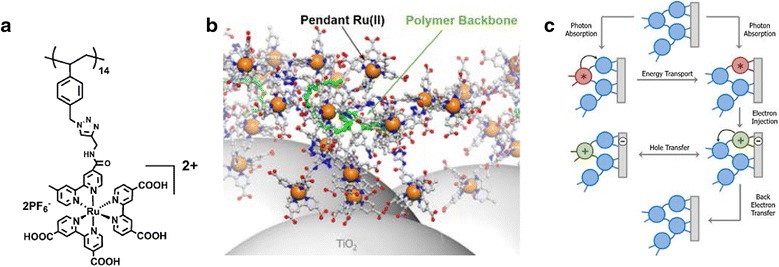

Instead of electropolymerization of Ru(II) polypyridyl chromophore onto a TiO2 surface, Leem et al. [19] reported the preparation of conjugated and non-conjugated [18] polymer-based Ru(II) chromophores with carboxylic acid anchoring groups followed by covalent immobilization of the polymeric chromophores to the surface of semiconductor nanoparticles. The carboxylic acid-derivatized ruthenium-functionalized polymer, PS-Ru-A, was obtained by a NMP method and click assembly via an azide-alkyne Huisgen cycloaddition reaction allowing the attachment of Ru(II) polypyridyl to the polystyrene backbone as shown in Fig. 4. PS-Ru-A was anchored to mesoporous TiO2 films (TiO2//PS-Ru-A) in order to understand the interfacial photophysical dynamics of energy and charge transport among tand he pendant complexes along the polymer chain at the interfaces. The MLCT exciton from Ru(II) diffuses efficiently among pendant Ru complexes that are attached along the polymer backbone. Based on transient absorption spectra and time-resolved emission spectra measurements, an antenna effect of the assembly occurs in TiO2//PS-Ru-A consisting of the following photophysical events; (1) photoexcitation of surface-bound RuII chromophores and electron injection into TiO2 on the picosecond time scale, (2) multiple Ru* → Ru energy hopping events after photoexcitation of unbound RuII chromophores followed by electron injection, (3) intra-assembly hole transfer to pendant complexes away from the TiO2 surface, and (4) back electron transfer between RuIII and TiO2(e−).

Fig. 4.

a Structure of carboxylic acid-derivatized polymer, PS-Ru-A. b Cartoon of PS-Ru-A anchored to a TiO2 nanoparticle surface. c Schematic representation of the photophysical events of the PS-Ru-A assembly at the surface of TiO2. The blue circles represent Ru(L)32 + chromophores while the green and red circles correspond to Ru(L)3+3 and Ru(L)2+*3

(Reproduced with permission from Ref. [18]. Copyright 2016, Wiley–VCH Verlag Gmbh & Co)

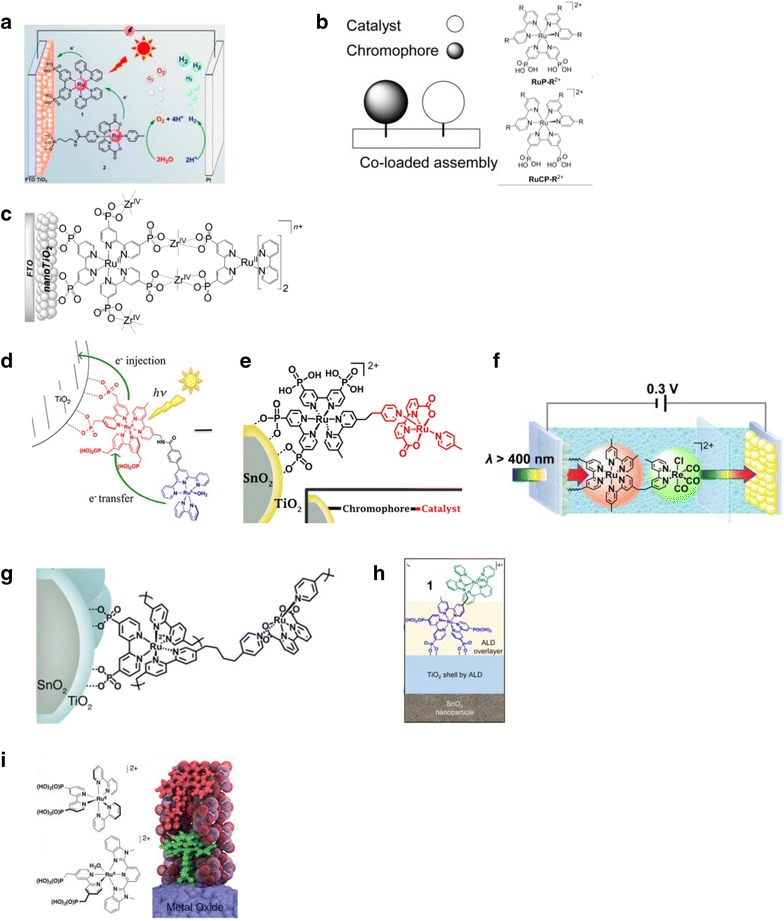

Polymer chromophore–catalyst assemblies for solar energy conversion

Multiple strategies have been explored for assembling chromophores and catalysts onto semiconductors including co-loading of chromophore and catalyst species [38, 39], forming bilayer assemblies with Zr(IV)-phosphate bridges [40], adsorbing pre-synthesized covalently linked chromophore–catalyst assemblies [41–44], electro-assembly by reductive vinyl coupling [45, 46], and the deposition of molecular overlayers [47, 48]. An example of a pre-synthesized chromophore–catalyst assembly is shown in Fig. 5, and this approach often requires multistep procedures with poor overall yields. The co-loading strategy requires less synthetic effort with the use of discrete chromophore and catalyst species but with the trade-off of less control of the orientation between the components and less special separation between catalyst and oxide surface. The use of metal cation bridged bilayers addresses the latter shortcoming of co-immobilization by allowing the sequential surface deposition of the phosphate-derivatized chromophore and catalyst species, with the catalyst not in direct contact with the semiconductor surface. While this gives a similar hierarchal surface structure with less synthetic effort as with the use pre-synthesized assemblies, the metal bridge is susceptible to hydrolysis and is generally unstable over long times.

Fig. 5.

a, b Co-loaded assembly on TiO2 [38, 39]. c Bilayer assembly with Zr(IV) bridging on TiO2 [40]. (d–f) Surface formed with pre-synthesized chromophore–catalyst assemblies [41–44]. g, h Electro-assembly by reductive vinyl coupling [45, 46]. i Molecular overlayers [48]

(Reproduced with permission from Ref. [38, 39]. Copyright 2012, WILEY‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co., 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016, and 2017, American Chemical Society, and 2015, The Royal Society of Chemistry)

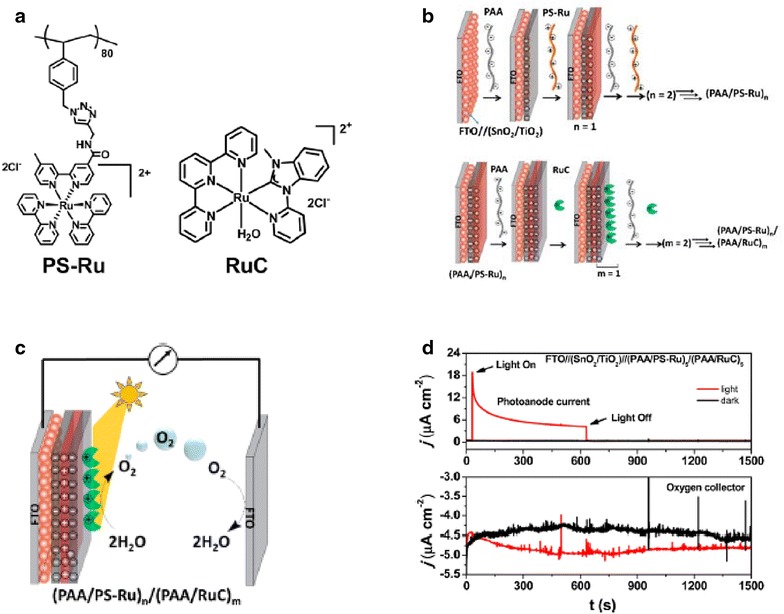

Our group has been interested in developing a different method for preparing dye-sensitized photoelectrode surfaces referred to as the ‘layer-by-layer’ (LbL) strategy using polychromophore–catalyst assemblies. Figure 6 illustrates the stepwise sequence of preparing an LbL surface with a polystyrene-based Ru polychromophore (PS-Ru) and the molecular water oxidation catalyst [Ru(tpy)(Mebim-py)(OH2)]2+ (Mebim-py = 2-pyridyl-N-methylbenzimidazole) (RuC) [26]. This sequence first involves the deposition of one to several layers of the cationic polymer chromophore chain, with the deposition of an anionic polymer alternated when depositing several thicknesses of the chromophore-containing polymer. The representative study in Fig. 6 details the use of polystyrene-based assemblies featuring pendant [Ru(bpy)3]2+ chromophores deposited onto mesoporous wide band gap metal oxide substrates, with alternating deposition of poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) as an oppositely charged polyelectrolyte via the LbL method. Following the adsorption of the PS-Ru layer, soaking the electrode in solution containing the RuC water oxidation catalyst introduces this species to the surface, with the catalyst layer thickness increased with alternating soakings in a PAA solution to build out RuC/PAA layers on the underlying PS-Ru/PAA surface.

Fig. 6.

a Structures of polychromophore (PS-Ru) and catalyst (RuC). b Schematic of the step-wise assembly of the LbL interface using a mesoporous SnO2/TiO2 core/shell layer deposited on a fluorine doped tin oxide (FTO) substrate. c Scheme depicting the C–G setup for detecting photochemically generated O2 by the (PAA/PS-Ru)n/(PAA/RuC)m prepared electrodes. d Current–time traces for the as prepared photoanode under bias with the simultaneous current response measured at the FTO collector electrode shown below

(Reproduced with permission from Ref. [26]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society)

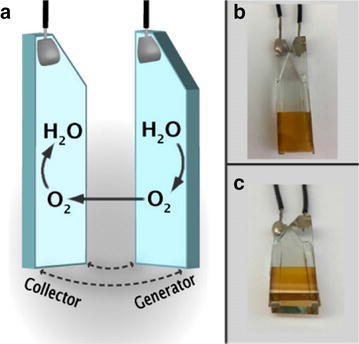

Photoelectrochemical investigations of PS-Ru/RuC were carried out to explore the ability of this surface to support light driven water oxidation in aqueous solution at pH 7 by using a collector-generator (C–G) dual working electrode cell. The C–G electrochemical setup is specifically designed to monitor the in situ photoelectrochemical production of O2 by dye-sensitized photoanodes, with the real time response of the setup providing additional information on the photocatalytic stability of the photoanode as shown in Fig. 7 [46, 49, 50]. In addition to the as prepared dye-sensitized photoanode under study (the generator electrode), the C–G setup consists of a transparent FTO electrode (the collector electrode) held 1 mm from the photoanode surface with the conductive surfaces facing. Narrow, 1 mm thick glass spacers are used to hold the two electrodes at the set distance, and the lateral edges are sealed with inert epoxy to create a small volume between the electrodes. When placed in solution, the volume fills with electrolyte via capillary action and serves to spatially constrain O2 produced at the photoanode for accurate detection and quantification at the collector [49].

Fig. 7.

a Collector–generator schematic and photographs of the front (b) and bottom (c) of an example C–G assembly consisting of a FTO|nanoTiO2 photoanode derivatized with a chromophore–catalyst assembly and a FTO collector electrode

(Reproduced with permission from ref [49]. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society)

Using the C–G setup, it was shown that the PS-Ru/RuC LbL system could carry out light driven water oxidation at a SnO2/TiO2 core/shell electrode with the best performance observed for FTO//(SnO2/TiO2)//(PAA/PS-Ru)5/(PAA/RuC)5 [26]. The photocurrent density of this photoanode was ca. 10 μA cm−2 after 30 s of illumination (0.44 V vs. NHE bias) and the C–G analysis showed the generation of O2 with a 22% Faradaic efficiency. This performance mirrored other DSPEC studies using the same RuC catalyst with more modest overall photocurrent densities than observed compared to the use of [Ru(bda)(L)2]-type water oxidation catalysts (bda = 2,2′-bipyridine-6,6′-dicarboxylate; L = neutral donor ligand) [51–53]. The performance of the PS-Ru/RuC LbL system did demonstrate the viability of this approach for to preparing photoelectrode interfaces and improvement will likely occur through further optimization of the LbL deposition strategy and introduction of more active molecular catalysts such as [Ru(bda)(L)2].

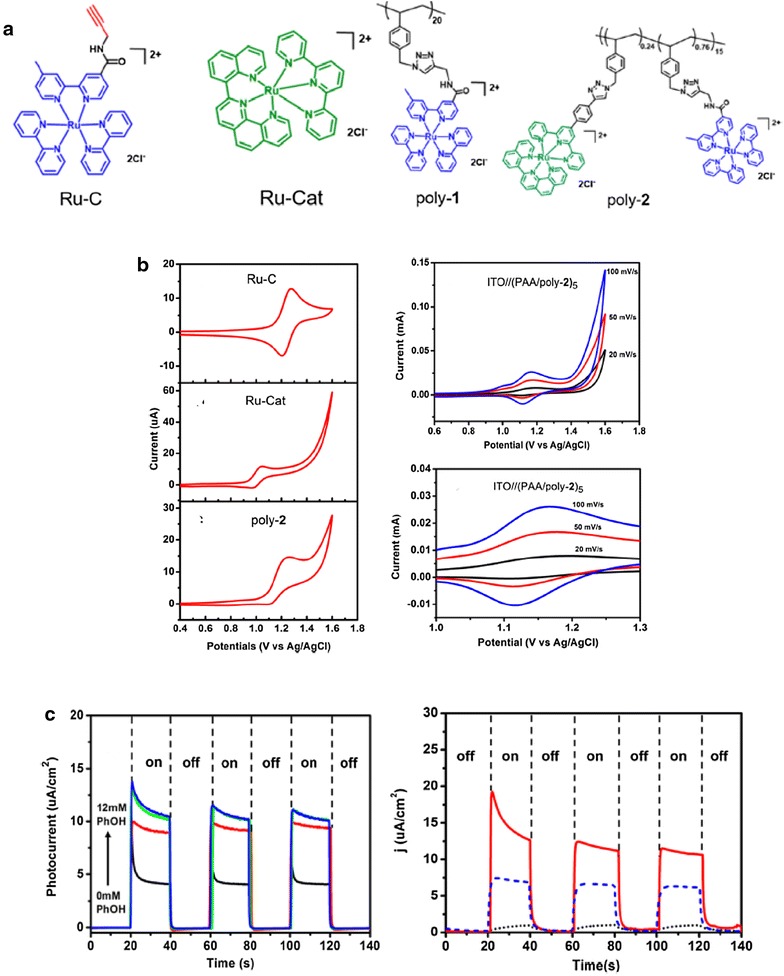

Recently, we elaborated on the LbL method with the use of a covalently linked Ru chromophore–catalyst polymeric assembly [27]. In contrast with the previous LbL study which involved the surface deposition of individual cationically charged Ru-C complexes, in this study the catalyst [Ru(trpy)(phenq)]2+ (Ru-Cat; troy = 2,2′:6,2″-terpyridine; phenq = 2-(quinol-8′-yl)-1,10-phenanthroline) was incorporated onto the same polymer backbone as the chromophore, and then deposited onto a mesoporous substrate via the LbL method. This approach enables the control of the chromophore-to-catalyst ratio within the polymer assembly. The chemical structure of a representative polymer, poly-2, is shown in Fig. 8. The Ru-Cat water oxidation catalyst and Ru-C chromophore moieties were attached to a polystyrene backbone via an azide-alkyne Huisgen cycloaddition reaction, with the relative ratio of the alkyne precursors of the chromophore and catalyst added to the click reaction feed dictating the ratio of each in the final polymer construct. Both 1H NMR and the comparison of the absorbance spectrum of the polymer with simulated component spectra of the Ru-C and Ru-Cat complexes verified the incorporation of each in the desired ratio into the final polymer strand.

Fig. 8.

a Structures of Ru–C, Ru-Cat, poly-1, and poly-2. b Cyclic voltammograms of the indicated species in solution (left) and of the LbL films on an ITO electrode (right). c Photocurrent activity of FTO//nanoTiO2//(PAA/poly-2)10 with increasing concentrations of phenol in solution (left) and of FTO//(SnO2/TiO2)//(PAA/poly-2)5 (red), FTO//(SnO2/TiO2)//(PAA/poly-1)5 (blue, dashed), and FTO//(SnO2/TiO2) (black, dotted) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 7

(Reproduced with permission from Ref. [27]. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society)

Electrochemical analysis of poly-2 showed behavior characteristic of both the Ru-C and Ru-Cat subunits (Fig. 8b). While the poly-2 shows an anodic wave for the RuIII/II couple of the Ru-C component at 1.2 V vs NHE and a catalytic wave at Eapp > 1.4 V vs NHE characteristic of Ru-Cat, the oxidation of the Ru-C is irreversible in the polymer. This was taken as evidence for hole transfer from Ru-C III to Ru-Cat within the polymer structure. FTO//nanoTiO2 photoanodes with 10 LbL layers of PAA/poly-2 were active for the light driven oxidation of phenol or benzyl alcohol, with the photocurrent response increasing with an increase in concentration of the organic substrate (Fig. 8c). Light driven water oxidation was investigated with 5 LbL layer thick polyacrylic acid (PAA)/poly-2 on FTO//(SnO2/TiO2) core/shell electrodes (FTO//(SnO2/TiO2)//(PAA/poly-2)5) which gave a twofold enhanced photocurrent response compared to FTO//(SnO2/TiO2)//(PAA/poly-1)5 (poly-1 containing only Ru-C with no Ru-Cat moieties present in the polymer). This was taken as likely evidence for light driven water oxidation though the generation of O2 was not quantified.

Summary

In this review, we summarize a series of polymeric assemblies consisting of multiple Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes prepared by using several polymerization methods including living anionic polymerization, RAFT, ATRP and NMP, followed by postreaction such as amidation reaction and click chemistry for the attachment of Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes to the polymer backbone. We describe the structure and dynamics of these polymer assemblies on mesoporous structure semiconductor films. Polymeric chromophore–catalyst assembly specifically containing chromophore units and an oxidation catalyst was developed to demonstrate its use in light-driven water oxidation at a photoanode-solution interface for a DSPEC application.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This material is based on work supported solely as part of the UNC EFRC: Solar Fuels and Next Generation Photovoltaics, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award Number DE-SC0001011.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Gyu Leem, Phone: +1-210-458-7050, Email: gyu.leem@utsa.edu.

Benjamin D. Sherman, Email: b.d.sherman@tcu.edu

Kirk S. Schanze, Phone: +1-210-458-6813, Email: kirk.schanze@utsa.edu

References

- 1.High JS, Rego LGC, Jakubikova E. Quantum dynamics simulations of excited state energy transfer in a zinc-free-base porphyrin dyad. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2016;120:8075–8084. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b05739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y, Lee JH, Ha H, Im SW, Nam KT. Material science lesson from the biological photosystem. Nano Converg. 2016;3:19. doi: 10.1186/s40580-016-0079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morseth ZA, Wang L, Puodziukynaite E, Leem G, Gilligan AT, Meyer TJ, Schanze KS, Reynolds JR, Papanikolas JM. Ultrafast dynamics in multifunctional Ru(II)-loaded polymers for solar energy conversion. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:818–827. doi: 10.1021/ar500382u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu C, Dasgupta NP, Yang P. Semiconductor nanowires for artificial photosynthesis. Chem. Mater. 2014;26:415–422. doi: 10.1021/cm4023198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennaman MK, Dillon RJ, Alibabaei L, Gish MK, Dares CJ, Ashford DL, House RL, Meyer GJ, Papanikolas JM, Meyer TJ. Finding the way to solar fuels with dye-sensitized photoelectrosynthesis cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:13085–13102. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer T, Papanikolas J, Heyer C. Solar Fuels and next generation photovoltaics: the UNC-CH energy frontier research center. Catal. Lett. 2011;141:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10562-010-0495-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan DM, Coggins MK, Concepcion JJ, Ashford DL, Fang Z, Alibabaei L, Ma D, Meyer TJ, Waters ML. Synthesis and electrocatalytic water oxidation by electrode-bound helical peptide chromophore–catalyst assemblies. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:8120–8128. doi: 10.1021/ic5011488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bettis SE, Ryan DM, Gish MK, Alibabaei L, Meyer TJ, Waters ML, Papanikolas JM. Photophysical characterization of a helical peptide chromophore-water oxidation catalyst assembly on a semiconductor surface using ultrafast spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:6029–6037. doi: 10.1021/jp410646u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashford DL, Lapides AM, Vannucci AK, Hanson K, Torelli DA, Harrison DP, Templeton JL, Meyer TJ. Water oxidation by an electropolymerized catalyst on derivatized mesoporous metal oxide electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:6578–6581. doi: 10.1021/ja502464s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alstrum-Acevedo JH, Brennaman MK, Meyer TJ. Chemical approaches to artificial photosynthesis. 2. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:6802–6827. doi: 10.1021/ic050904r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashford DL, Gish MK, Vannucci AK, Brennaman MK, Templeton JL, Papanikolas JM, Meyer TJ. Molecular chromophore–catalyst assemblies for solar fuel applications. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:13006–13049. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Puodziukynaite E, Grumstrup EM, Brown AC, Keinan S, Schanze KS, Reynolds JR, Papanikolas JM. Ultrafast formation of a long-lived charge-separated state in a Ru-loaded poly(3-hexylthiophene) light-harvesting polymer. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:2269–2273. doi: 10.1021/jz401089v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Puodziukynaite E, Vary RP, Grumstrup EM, Walczak RM, Zolotarskaya OY, Schanze KS, Reynolds JR, Papanikolas JM. Competition between ultrafast energy flow and electron transfer in a Ru(II)-loaded polyfluorene light-harvesting polymer. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:2453–2457. doi: 10.1021/jz300979j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang Y-Q, Taylor NJ, Laverdière F, Hanan GS, Loiseau F, Nastasi F, Campagna S, Nierengarten H, Leize-Wagner E, Van Dorsselaer A. Ruthenium(II) complexes with improved photophysical properties based on planar 4′-(2-Pyrimidinyl)-2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:2854–2863. doi: 10.1021/ic0622609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooke MW, Hanan GS, Loiseau F, Campagna S, Watanabe M, Tanaka Y. Self-assembled light-harvesting systems: Ru(II) complexes assembled about Rh–Rh cores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10479–10488. doi: 10.1021/ja072153t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuccitto N, Torrisi V, Cavazzini M, Morotti T, Puntoriero F, Quici S, Campagna S, Licciardello A. Stepwise formation of ruthenium(II) complexes by direct reaction on organized assemblies of thiol-terpyridine species on gold. ChemPhysChem. 2007;8:227–230. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200600573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JY, Zhu K, Neale NR, Frank AJ. Transparent TiO2 nanotube array photoelectrodes prepared via two-step anodization. Nano Converg. 2014;1:9. doi: 10.1186/s40580-014-0009-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leem G, Morseth ZA, Wee K-R, Jiang J, Brennaman MK, Papanikolas JM, Schanze KS. Polymer-based ruthenium(II) polypyridyl chromophores on TiO2 for solar energy conversion. Chem. Asian J. 2016;11:1257–1267. doi: 10.1002/asia.201501384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leem G, Morseth ZA, Puodziukynaite E, Jiang J, Fang Z, Gilligan AT, Reynolds JR, Papanikolas JM, Schanze KS. Light harvesting and charge separation in a π-conjugated antenna polymer bound to TiO2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:28535–28541. doi: 10.1021/jp5113558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang Z, Ito A, Stuart AC, Luo H, Chen Z, Vinodgopal K, You W, Meyer TJ, Taylor DK. Soluble reduced graphene oxide sheets grafted with polypyridylruthenium-derivatized polystyrene brushes as light harvesting antenna for photovoltaic applications. ACS Nano. 2013;7:7992–8002. doi: 10.1021/nn403079z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang Z, Ito A, Keinan S, Chen Z, Watson Z, Rochette J, Kanai Y, Taylor D, Schanze KS, Meyer TJ. Atom transfer radical polymerization preparation and photophysical properties of polypyridylruthenium derivatized polystyrenes. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:8511–8520. doi: 10.1021/ic400520m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Y, Chen Z, Puodziukynaite E, Jenkins DM, Reynolds JR, Schanze KS. Light harvesting arrays of polypyridine ruthenium(II) chromophores prepared by reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerization. Macromolecules. 2012;45:2632–2642. doi: 10.1021/ma202804u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leem G, Keinan S, Jiang J, Chen Z, Pho T, Morseth ZA, Hu Z, Puodziukynaite E, Fang Z, Papanikolas JM, Reynolds JR, Schanze KS. Ru(bpy)32+ derivatized polystyrenes constructed by nitroxide-mediated radical polymerization. Relationship between polymer chain length, structure and photophysical properties. Polym. Chem. 2015;6:8184–8193. doi: 10.1039/C5PY01289A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Younathan JN, McClanahan SF, Meyer TJ. Synthesis and characterization of soluble polymers containing electron- and energy-transfer reagents. Macromolecules. 1989;22:1048–1054. doi: 10.1021/ma00193a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dupray LM, Meyer TJ. Synthesis and characterization of amide-derivatized, polypyridyl-based metallopolymers. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:6299–6307. doi: 10.1021/ic9516222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leem G, Sherman BD, Burnett AJ, Morseth ZA, Wee K-R, Papanikolas JM, Meyer TJ, Schanze KS. Light-driven water oxidation using polyelectrolyte layer-by-layer chromophore–catalyst assemblies. ACS Energy Lett. 2016;1:339–343. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.6b00171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang J, Sherman BD, Zhao Y, He R, Ghiviriga I, Alibabaei L, Meyer TJ, Leem G, Schanze KS. Polymer chromophore–catalyst assembly for solar fuel generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:19529–19534. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b05173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlenoff JB, Ly H, Li M. Charge and mass balance in polyelectrolyte multilayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:7626–7634. doi: 10.1021/ja980350+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu A, Yoo D, Lee JK, Rubner MF. Solid-state light-emitting devices based on the tris-chelated ruthenium(II) Complex: 3. High efficiency devices via a layer-by-layer molecular-level blending approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:4883–4891. doi: 10.1021/ja9833624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnston APR, Cortez C, Angelatos AS, Caruso F. Layer-by-layer engineered capsules and their applications. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006;11:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2006.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilbat A-M, Szegletes Z, Kóta Z, Ball V, Schaaf P, Voegel J-C, Szalontai B. Phospholipid bilayers as biomembrane-like barriers in layer-by-layer polyelectrolyte films. Langmuir. 2007;23:8236–8242. doi: 10.1021/la700839p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White N, Misovich M, Yaroshchuk A, Bruening ML. Coating of nafion membranes with polyelectrolyte multilayers to achieve high monovalent/divalent cation electrodialysis selectivities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:6620–6628. doi: 10.1021/am508945p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toellner L, Fischlechner M, Ferko B, Grabherr RM, Donath E. Virus-coated layer-by-layer colloids as a multiplex suspension array for the detection and quantification of virus-specific antibodies. Clin. Chem. 2006;52:1575–1583. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.065789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dupray LM, Devenney M, Striplin DR, Meyer TJ. An antenna polymer for visible energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:10243–10244. doi: 10.1021/ja970660c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friesen DA, Kajita T, Danielson E, Meyer TJ. Preparation and photophysical properties of amide-linked, polypyridylruthenium-derivatized polystyrene. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:2756–2762. doi: 10.1021/ic9710420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang Z, Keinan S, Alibabaei L, Luo H, Ito A, Meyer TJ. Controlled electropolymerization of ruthenium(II) vinylbipyridyl complexes in mesoporous nanoparticle films of TiO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:4872–4876. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lapides AM, Ashford DL, Hanson K, Torelli DA, Templeton JL, Meyer TJ. Stabilization of a ruthenium(II) polypyridyl dye on nanocrystalline TiO2 by an electropolymerized overlayer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:15450–15458. doi: 10.1021/ja4055977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheridan MV, Sherman BD, Coppo RL, Wang D, Marquard SL, Wee KR, Murakami Iha NY, Meyer TJ. Evaluation of Chromophore and Assembly Design in Light-Driven Water Splitting with a Molecular Water Oxidation Catalyst. ACS Energy Letters. 2016;1(1):231–236. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.6b00142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao Y, Ding X, Liu J, Wang L, Lu Z, Li L, Sun L. Visible light driven water splitting in a molecular device with unprecedentedly high photocurrent density. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:4219–4222. doi: 10.1021/ja400402d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanson K, Torelli DA, Vannucci AK, Brennaman MK, Luo H, Alibabaei L, Song W, Ashford DL, Norris MR, Glasson CRK, Concepcion JJ, Meyer TJ. Self-assembled bilayer films of ruthenium(II)/polypyridyl complexes through layer-by-layer deposition on nanostructured metal oxides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:12782–12785. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashford DL, Song W, Concepcion JJ, Glasson CRK, Brennaman MK, Norris MR, Fang Z, Templeton JL, Meyer TJ. Photoinduced electron transfer in a chromophore–catalyst assembly anchored to TiO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:19189–19198. doi: 10.1021/ja3084362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sherman BD, Xie Y, Sheridan MV, Wang D, Shaffer DW, Meyer TJ, Concepcion JJ. Light-driven water splitting by a covalently linked ruthenium-based chromophore–catalyst assembly. ACS Energy Lett. 2017;2:124–128. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.6b00661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sahara G, Kumagai H, Maeda K, Kaeffer N, Artero V, Higashi M, Abe R, Ishitani O. Photoelectrochemical reduction of CO2 coupled to water oxidation using a photocathode with a Ru(II)–Re(I) complex photocatalyst and a CoOx/TaON photoanode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:14152–14158. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamamoto M, Wang L, Li F, Fukushima T, Tanaka K, Sun L, Imahori H. Visible light-driven water oxidation using a covalently-linked molecular catalyst-sensitizer dyad assembled on a TiO2 electrode. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:1430–1439. doi: 10.1039/C5SC03669K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherman BD, Ashford DL, Lapides AM, Sheridan MV, Wee K-R, Meyer TJ. Light-Driven Water Splitting with a Molecular Electroassembly-Based Core/Shell Photoanode. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:3213–3217. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sherman BD, Sheridan MV, Wee K-R, Marquard SL, Wang D, Alibabaei L, Ashford DL, Meyer TJ. A dye-sensitized photoelectrochemical tandem cell for light driven hydrogen production from water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:16745–16753. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wee K-R, Brennaman MK, Alibabaei L, Farnum BH, Sherman B, Lapides AM, Meyer TJ. Stabilization of ruthenium(II) polypyridyl chromophores on nanoparticle metal-oxide electrodes in water by hydrophobic PMMA overlayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13514–13517. doi: 10.1021/ja506987a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lapides AM, Sherman BD, Brennaman MK, Dares CJ, Skinner KR, Templeton JL, Meyer TJ. Synthesis, characterization, and water oxidation by a molecular chromophore–catalyst assembly prepared by atomic layer deposition. The “mummy” strategy. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:6398–6406. doi: 10.1039/C5SC01752A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sherman BD, Sheridan MV, Dares CJ, Meyer TJ. Two electrode collector-generator method for the detection of electrochemically or photoelectrochemically produced O2. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:7076–7082. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wee K-R, Sherman BD, Brennaman MK, Sheridan MV, Nayak A, Alibabaei L, Meyer TJ. An aqueous, organic dye derivatized SnO2/TiO2 core/shell photoanode. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016;4:2969–2975. doi: 10.1039/C5TA06678F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coppo RL, Farnum BH, Sherman BD, Iha NYM, Meyer TJ. The role of layer-by-layer, compact TiO2 films in dye-sensitized photoelectrosynthesis cells. Sustain. Energy Fuels. 2017;1:112–118. doi: 10.1039/C6SE00022C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alibabaei L, Brennaman MK, Norris MR, Kalanyan B, Song W, Losego MD, Concepcion JJ, Binstead RA, Parsons GN, Meyer TJ. Solar water splitting in a molecular photoelectrochemical cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:20008–20013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319628110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meyer TJ, Sheridan MV, Sherman BD. Mechanisms of molecular water oxidation in solution and on oxide surfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46:6148–6169. doi: 10.1039/C7CS00465F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]