ABSTRACT

The steps by which Escherichia coli strains harboring mutations related to fosfomycin (FOS) resistance arise and spread during urinary tract infections (UTIs) are far from being understood. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of urine, pH, and anaerobiosis on FOS activity against a set of isogenic strains carrying the most prevalent chromosomal mutations conferring FOS resistance (ΔuhpT, ΔglpT, ΔcyaA, and ΔptsI), either singly or in combination. We also studied fosfomycin-resistant E. coli clinical isolates from patients with UTI. Our results demonstrate that urinary tract physiological conditions might have a profound impact on FOS activity against strains with chromosomal FOS resistance mutations. Specifically, acidic pH values and anaerobiosis convert most of the strains categorized as resistant to fosfomycin according to the international guidelines to a susceptible status. Therefore, urinary pH values may have practical interest in the management of UTIs. Finally, our results, together with the high fitness cost associated with FOS resistance mutations, might explain the low prevalence of fosfomycin-resistant E. coli variants in UTIs.

KEYWORDS: fosfomycin activity, fosfomycin resistance, chromosomal mutations, UTI, Escherichia coli, urinary tract infection

INTRODUCTION

Fosfomycin (FOS) is a phosphonic acid derivative produced by a broad variety of Streptomyces and Pseudomonas species (1). Since the discovery of FOS in 1969 (2), this natural antibiotic has attracted considerable clinical and scientific interest due to its broad-spectrum bactericidal activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (3–5). FOS distributes adequately to different tissues, such as the bladder, kidneys, lungs, bones, cerebrospinal fluid, and heart valves (6–10). Moreover, given the worrisome increase of multidrug-resistant pathogens (11), FOS has been reconsidered as a treatment option in numerous clinical guidelines and trials for the treatment of a wide range of infections (4, 12–15).

FOS has been used widely as a first-line agent for the empirical treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) (5). In Escherichia coli, the most prevalent causative organism of UTI (16, 17), FOS is actively transported into the bacterial cytoplasm via glycerol-3-phospate (GlpT) and glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) (UhpT) transporters (18). Because the presence of G6P acts as an inducer of the UhpT transporter, FOS susceptibility testing is performed in the presence of G6P to induce FOS susceptibility. Once FOS has reached the cytoplasm, it acts as a phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) analogue, binding to MurA (UDP-N-acetylglucosamine enolpyruvyl transferase) covalently, preventing the formation of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-3-enolpyruvate from PEP and N-acetylglucosamine (18, 19), and thus interfering with the first step of bacterial cell wall biosynthesis.

FOS resistance determinants are either chromosomal or plasmid mediated (1, 5). Chromosomally mediated FOS resistance can be achieved by reducing permeability to FOS through mutations in genes encoding the GlpT and UhpT transporters or their regulators. Permeability can also be reduced by mutations in the cyaA and/or ptsI genes, which control the intracellular cAMP levels necessary for activation of FOS transporters (20, 21). Regarding the FOS target, mutations in murA that decrease the affinity of MurA for FOS also reduce susceptibility (22). In addition, overexpression of murA has also been related to FOS resistance (23). However, few reports of clinical isolates have shown mutations in the murA gene, and none in the catalytic site of MurA, because most of them drastically reduce bacterial cell viability (24).

Ballestero-Téllez and colleagues (25) recently demonstrated that the presence of single chromosomal mutations producing loss of function, as well as some of their combinations, confer low-level FOS resistance (LLFR) but not clinical resistance according to international guidelines. Although the presence of LLFR mutations yields an FOS-susceptible phenotype, they may act as gateways for highly resistant subpopulations by the selection of additional LLFR mutations (25, 26).

Despite the increased use of FOS for treatment of UTIs, the prevalence of clinical isolates with low- and high-level FOS resistance is still very low (27, 28). In particular, the low prevalence of strains harboring chromosomal mutations conferring FOS resistance has been attributed to the high biological cost, entailing a reduced fitness that compromises competition with the normal microbiota in the human host (29). The effect of FOS resistance mutations on fitness is particularly interesting in the case of uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC), because if the cost is high, the resistant bacteria will not grow at the minimal rate needed to establish infection (30, 31). However, FOS-resistant clinical isolates containing mutations in the above-cited chromosomal genes have been described (30, 32, 33). Moreover, because fitness costs can easily be ameliorated by compensatory mutations, as shown for other antibiotic resistance genes (34), additional explanations for the low prevalence of FOS-resistant strains can be invoked.

Recently, we showed that low-level-quinolone-resistant (LLQR) E. coli strains are already resistant to high concentrations of ciprofloxacin (CIP) under urinary tract conditions, including the presence of urine, urinary pH, and anaerobiosis (35, 36). The bladder environment is mainly anaerobic, with a concentration of dissolved oxygen (DO) in urine of about 4.2 ppm; the concentration is also variable and mainly reflects the renal metabolic state (37). Moreover, in patients with urinary infections, the urine DO concentration is significantly reduced as a result of oxygen consumption by the microbes (37). However, although the molecular mechanisms of chromosomal FOS resistance and their effects on bacterial fitness are relatively well known, there is a paucity of information about the impact of the urinary tract environment on the antimicrobial activity of FOS against strains harboring chromosomal FOS resistance mutations.

Given the above information, the main objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of the urinary tract environment on the antimicrobial activity of FOS against a set of well-characterized isogenic strains harboring the most frequent chromosomal FOS resistance mutations. A series of FOS-resistant E. coli clinical strains isolated from patients with UTI was also studied.

RESULTS

Effects of urine and pH on fitness of E. coli isogenic strains.

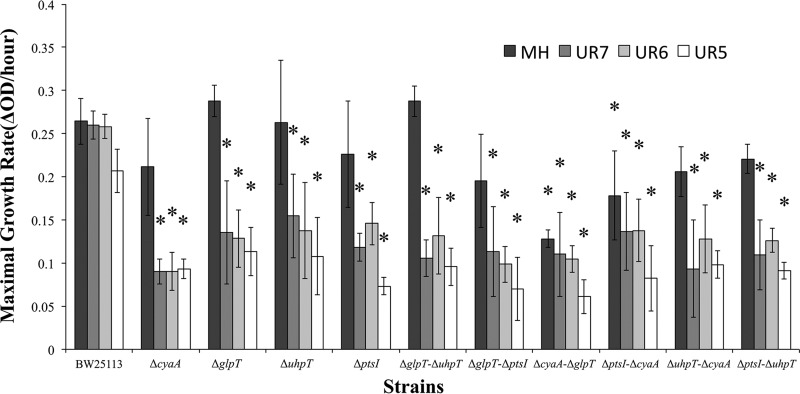

Figure 1 shows maximal growth rates per hour. Concerning growth in Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth, only the ΔcyaA ΔglpT and ΔptsI ΔcyaA strains showed significant reductions in the maximal growth rate compared to that of BW25113. Notably, all of the strains with single and double deletions showed statistically significant decreases in maximal growth rates in urine at different pH values compared to those for strain BW25113.

FIG 1.

In vitro maximal growth rates (ΔOD per hour) for strain BW25113 and 10 isogenic LLFR and FOS-resistant strains in MH broth and urine at different pH values. Error bars represent interquartile ranges. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 [Mann-Whitney U test]) between the indicated strains and wild-type strain BW25113 under the same conditions.

Effects of pH and anaerobiosis on FOS activity.

Table 1 shows that under standard conditions (MH broth, pH 7.4, aerobic), all strains harboring double deletions were fully resistant to FOS according to EUCAST criteria (37). Among the single mutants, only the ΔuhpT strain presented a MIC over the cutoff value.

TABLE 1.

MICs of fosfomycin with G6P (25 μg/ml) against isogenic E. coli strains in MH broth at different pH valuesa

| Strain | FOS MIC (μg/ml) in MH broth at pH: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 |

7.4 |

6 |

5 |

|||||

| O2 | nO2 | O2 | nO2 | O2 | nO2 | O2 | nO2 | |

| ATCC 25922 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| BW25113 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| ΔcyaA | 64 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| ΔglpT | 32 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| ΔuhpT | 128 | 16 | 64 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 16 |

| ΔptsI | 8 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| ΔglpT ΔuhpT | 512 | 256 | 256 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 32 |

| ΔglpT ΔptsI | 512 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| ΔcyaA ΔglpT | 1,024 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| ΔptsI ΔcyaA | 1,024 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 32 |

| ΔuhpT ΔcyaA | 1,024 | 128 | 512 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 32 |

| ΔptsI ΔuhpT | 1,024 | 8 | 128 | 8 | 128 | 8 | 128 | 8 |

MIC values indicating resistance (according to EUCAST guidelines) are shown in bold. O2, aerobic conditions; nO2, anaerobic conditions.

A remarkable impact of pH on FOS activity was observed. When susceptibility tests were performed at pH 8, all strains showed 2- to 16-fold MIC increases. However, at acidic pHs, most of the MIC values fell below the susceptibility cutoff. At pH 6, only the ΔglpT ΔuhpT, ΔuhpT ΔcyaA, and ΔptsI ΔuhpT strains remained resistant. This effect was even more evident at pH 5, demonstrating that low pH values lead to higher FOS activity against E. coli.

Regarding the effect of anaerobiosis, Table 1 (nO2 columns) shows that growth under anaerobiosis increased the effect of FOS at all pH values tested, with 2- to 128-fold reductions of MIC values compared to those under aerobic conditions. At pH 7.4 and with anaerobiosis, only three mutants (ΔglpT ΔuhpT, ΔglpT ΔptsI, and ΔuhpT ΔcyaA) remained resistant, with MICs just slightly over the susceptibility breakpoint. Further decreases of pH reduced the number of resistant strains, abolishing resistance completely at pH 5. Therefore, the combination of acidification and anaerobiosis increases susceptibility to FOS, even in strains with high resistance levels.

MIC determinations under urinary physiological conditions.

Some MIC changes were observed in urine at pH 7 under aerobic conditions compared to the MICs in MH broth at pH 7.4 (Table 2). Most of the strains showed minor MIC variations, but two single variants (ΔglpT and ΔptsI) displayed significant MIC increases (8-fold and 16-fold, respectively).

TABLE 2.

MICs of fosfomycin with G6P (25 μg/ml) against isogenic E. coli strains in MH broth and urine at different pH valuesa

| Strain | FOS MIC (μg/ml) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MH broth at pH 7.4 |

Urine at pH 7 |

Urine at pH 6 |

Urine at pH 5 |

|||||

| O2 | nO2 | O2 | nO2 | O2 | nO2 | O2 | nO2 | |

| ATCC 25922 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| BW25113 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| ΔcyaA | 16 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 16 |

| ΔglpT | 2 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| ΔuhpT | 64 | 16 | 64 | 16 | 32 | 8 | 16 | 2 |

| ΔptsI | 4 | 2 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| ΔglpT ΔuhpT | 256 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 8 | 8 |

| ΔglpT ΔptsI | 128 | 64 | 32 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 4 |

| ΔcyaA ΔglpT | 128 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| ΔptsI ΔcyaA | 128 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| ΔuhpT ΔcyaA | 512 | 128 | 256 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 64 |

| ΔptsI ΔuhpT | 128 | 8 | 256 | 32 | 256 | 32 | 64 | 8 |

MIC values indicating resistance (according to EUCAST guidelines) are shown in bold. O2, aerobic conditions; nO2, anaerobic conditions.

As previously observed in MH broth, acidification and anaerobic conditions increased the activity of FOS in the presence of urine. This activity was maximal at pH 5, with the notable exception of that of the ΔcyaA and ΔptsI single variants. Both strains maintained elevated MICs, though they were below the cutoff value for resistance. Also, the ΔcyaA ΔglpT and ΔuhpT ΔcyaA double mutant strains remained resistant, but with a MIC value (64 μg/ml) very close to the cutoff according to EUCAST. UTI conditions did not affect the activity of FOS against strains containing particular mutations. For instance, the susceptibility of strains harboring the ΔcyaA mutation (alone or combined) was poorly affected by the tested conditions.

The combination of urine, acidic pH, and anaerobiosis had a large effect on FOS activity, making most strains susceptible at pH 5 according to the international guidelines.

Effects of urine, pH, and anaerobiosis on FOS activity against E. coli clinical isolates.

To analyze the possibility that the effects observed were specific to strain BW25113, we evaluated the effects of urinary tract physiological conditions on fosfomycin-resistant E. coli clinical isolates from patients with UTI. Five FOS-resistant isolates were found among 404 UTI isolates (1.2%). The phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of these strains are shown in Table 3. As shown in Table 4, urine increased the MIC at neutral pH in all cases. Notably, acidification and anaerobiosis increased FOS activity in three of the five resistant strains (ECF33, ECF168, and ECF318). Interestingly, these are the only strains exhibiting mutations in the uhpT gene (ECF33 and ECF318) or the UhpT regulator genes uhpA, uhpB, and uhpC (ECF168 and ECF318).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of fosfomycin-resistant E. coli clinical strains

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) |

Amino acid substitution(s) encoded ina: |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microdilution | Etest | murA | glpT | uhpA | uhpB | uhpC | uhpT | ptsI | cyaA | crp | |

| ECF33 | 512 | >256 | ND | Deletion | ND | ND | ND | Deletion | K367R | ND | ND |

| ECF145 | 256 | 64 | ND | Deletion | ND | ND | ND | ND | K367R | ND | ND |

| ECF168 | 64 | 64 | ND | F297L, N348T, Q443E, E444Q | P79S | A205D | Y18H, G282D, T435A | ND | K367R | S142N, deletion | ND |

| ECF318 | 256 | >256 | ND | C99G, F297L, Q443E, E444Q, K448E | P79S | ND | I14M, Q17Y | Q351E | K367R | S142N, E349A, T352S, K356S, E359G, D362E | ND |

| ECF330 | 256 | >256 | ND | K448E | ND | ND | ND | ND | K367R | S142N, E349A, T352S, K356S, E359G, D362E | ND |

ND, not detected.

TABLE 4.

MICs of fosfomycin with G6P (25 μg/ml) against E. coli clinical strains in MH broth and urine at different pH valuesa

| Strain | FOS MIC (μg/ml) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MH broth at pH 7.4 |

Urine at pH 7 |

Urine at pH 6 |

Urine at pH 5 |

|||||

| O2 | nO2 | O2 | nO2 | O2 | nO2 | O2 | nO2 | |

| ECF33 | 512 | 64 | 512 | 256 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 16 |

| ECF145 | 256 | 256 | 512 | 1,024 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 |

| ECF168 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 16 | 32 | 8 | 16 | 8 |

| ECF318 | 256 | 64 | 512 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 16 |

| ECF330 | 256 | 128 | 1,024 | 1,024 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 128 |

MIC values indicating resistance (according to EUCAST guidelines) are shown in bold. O2, aerobic conditions; nO2, anaerobic conditions.

DISCUSSION

FOS resistance has previously been related to a high biological cost, entailing reduced fitness, which compromises the competition with the normal microbiota in the human host (29). The effect of FOS resistance mutations on fitness is of particular interest in the case of UPEC strains, because if the cost is sufficiently high, resistant bacteria will not grow at the minimal rate needed to establish infection (30). We evaluated the impacts of urinary physiological conditions on the growth of isogenic strains displaying low and high levels of resistance to FOS and carrying the most prevalent FOS chromosomal mutations, singly and in combination, and we compared the results obtained to those for strains grown in MH broth. Interestingly, all the isogenic strains showed significant reductions in the maximal growth rate in urine compared to that of wild-type strain BW25113. Thus, the low prevalence of FOS-resistant strains can be explained in part by the high biological cost that these mutations promote under urinary tract conditions in the absence of FOS, confirming previous results (28). In this way, mutations related to the cyaA and ptsI genes lead to lower levels of cAMP, reducing UhpT and GlpT channel expression, pilus biosynthesis, or virulence factors (28). Concerning the presence of double deletions, the ΔcyaA ΔglpT and ΔptsI ΔcyaA strains showed the highest reductions in the maximal growth rate in MH broth.

We previously showed that FOS MIC determination may not be an accurate predictor of FOS efficacy (25, 38). Susceptibility testing gives a measure of growth inhibition (MIC) under specific in vitro conditions. However, its clinical usefulness requires the extrapolation of these MIC values into a prediction of clinical outcome (39). MH broth is the medium of choice for susceptibility testing of commonly isolated aerobic or facultative organisms (40). This medium shows acceptable batch-to-batch reproducibility and a low concentration of inhibitors, with a stable pH value of 7.2 to 7.4, supporting satisfactory growth of most common pathogens. Nevertheless, the scenario in which antibiotics must act during UTI treatment is quite different. In the urinary tract, the presence of urine, low pH values, and an anaerobic atmosphere has been related to modulation of antibiotic effectiveness (35, 41, 42). Therefore, the activity of FOS under laboratory and UTI conditions is expected to be different.

Our results confirm that low pH values increase FOS activity (41, 43). In an acidic urine (pH values of 5 to 6), FOS is partially protonated and in a more lipophilic state, allowing FOS to enter bacteria and resulting in higher antimicrobial activity (43). As we previously demonstrated, the urine pH for patients with UTI caused by E. coli is mainly acidic (85.38% of patients have a urine pH of ≤6.5) (35). Therefore, urine physiological pH values may improve the effect of FOS in these patients. Additionally, growth under anaerobic conditions has also been related to increased antibacterial activity of FOS due to elevated expression of GlpT and UhpT after activation of FNR, leading to increased FOS uptake (44). The results obtained in our study support this finding, with 2- to 32-fold MIC reductions observed under anaerobic conditions. However, the effect of urine on FOS activity is weak. These data agree with those of Bergogne-Bérézin et al., who showed that urine slightly decreases the in vitro susceptibility to FOS (45).

The observed effect is not exclusive to strain BW25113 and its derivatives, as urine acidification and anaerobiosis increased FOS activity against three of the five FOS-resistant clinical strains tested. Interestingly, the three strains had mutations or deletions in the uhpT gene or in genes related to UhpT expression.

Despite the increased use of FOS for treatment of UTIs, there is a very low prevalence of FOS-resistant E. coli strains, particularly those harboring chromosomal mutations conferring FOS resistance (27, 28). Overall, our results demonstrate that urinary tract physiological conditions might have a profound impact on FOS activity, specifically against strains with common FOS resistance mutations. Here we have shown that urine acidification and anaerobiosis increase FOS activity on E. coli strains with low- and high-level FOS resistance due to mutations in chromosomal genes, adding an additional explanation for the low prevalence of FOS-resistant E. coli variants in UTIs.

The existence of strains harboring chromosomal FOS resistance mutations isolated from patients with UTI nevertheless suggests that mutations that compensate for the cost of FOS resistance are being selected in clinical settings. Also, clinical features may play an important role in the survival and selection of FOS-resistant mutant strains. For instance, pregnant women have an increased glomerular filtration rate and higher urinary calcium excretion throughout pregnancy, with higher urine pH values in the second and third trimesters (46). Thiazide diuretic intake is also associated with a higher urine pH by reducing urinary uric acid excretion (47). Furthermore, there are genetic disorders that are related to urine alkalization. Gitelman syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder of the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter, expressed at the distal convoluted tubule, which is accompanied by an inappropriately high urine pH (48). Thus, there are cases in which an alkaline pH of urine can partially compromise the activity of FOS and select for mutations conferring low-level FOS resistance. Further work needs to be done to understand the mechanisms by which strains with FOS resistance mutations are selected during treatment of UTI with FOS. Experiments with an animal model of UTI are being performed in order to establish the in vivo correlation with the in vitro results.

The effect of urinary tract conditions on FOS activity is just the opposite of that on ciprofloxacin, i.e., ciprofloxacin activity decreases with acidity and anaerobiosis (35), making it possible to choose between two alternative treatments. Thus, urinary pH values may have practical interest in the management of UTIs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture.

E. coli BW25113 and 10 isogenic strains, constructed by Ballesteros-Téllez et al. (25) and carrying the most prevalent FOS chromosomal mutations (ΔglpT, ΔuhpT, ΔcyaA, and ΔptsI), singly and in combination, were studied. E. coli ATCC 25922 was also used as a control strain for susceptibility assays. Additionally, five FOS-resistant E. coli strains isolated from patients with UTI were included.

From March to May 2016, 404 UPEC strains from patients attending the Virgen del Rocío University Hospital were selected using a systematic random sampling. Bacterial isolates were identified to the species level by use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), and antibiotic susceptibility was determined using a MicroScan WalkAway Plus system (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, West Sacramento, CA). For all the strains that showed resistance to FOS according to EUCAST criteria (49), Etest (Liofilchem, Italy) was performed in order to verify this phenotype. Strains categorized as resistant by microdilution and Etest were included in this study. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío.

Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth (Conda Pronadisa, Spain) at pH 7.4 was used as a control medium. Urine obtained from 5 healthy volunteers who had not received antibiotic treatment during the previous 6 months was used as culture medium. Urine samples were pooled and sterilized by filtration through 0.22-mm-pore-size filters (polyethersulfone [PES] membrane) (VWR, United Kingdom) and stored at −20°C. Before sample use, the urine pH was adjusted to values of 5.0, 6.0, and 7.0 with HCl or NaOH (Sigma-Aldrich, Spain), and samples were sterilized again by filtration. Sterility was verified by incubating aliquots of each sample at 37°C for 24 h.

Growth rate measurements.

In vitro growth rates were determined for E. coli BW25113 and mutant derivatives, as follows. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in MH broth and cultured at 37°C and 180 rpm for 2 h to reach the exponential growth phase. Approximately 105 cells were then inoculated into fresh medium (MH broth or urine at pH values of 5, 6, and 7.4). Plates were incubated on an automated microplate reader (Infinite M200; Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) at 37°C for 24 h, and the absorbance at 595 nm for each well was measured every 30 min after strong shaking. Growth assays were performed on three different days (five replicates per day), using clear, flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) containing 100 μl of either pH-adjusted urine or MH broth. To determine the maximal growth rate (50), the difference between every two consecutive optical density (OD) values was calculated for the exponential growth phase, using a total of 15 replicates per strain. The median of the 15 highest ΔOD values was calculated for each strain, corresponding to the maximal growth rate. Statistical differences between mutants and wild-type BW25113 were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Susceptibility testing.

MICs of FOS were determined in triplicate by using broth microdilution methods according to EUCAST guidelines (49). Also, gradient MIC strip experiments (MIC test strips [Liofilchem, Italy] supplemented with G6P) were performed on MH agar, and plates were incubated under aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Aanerogen; Oxoid) for 24 h at 37°C. To evaluate the effect of pH, MICs were determined in MH broth at pH 5, 6, 7.4, and 8. To reproduce UTI physiological conditions, MICs of FOS were also measured in urine at pH values of 5, 6, and 7 (pH 8 could not be tested in urine because massive precipitation of salts precluded bacterial growth detection). Plates were incubated for 24 h under aerobic and anaerobic conditions at 37°C.

Molecular detection of FOS resistance genes.

Genes conferring resistant to fosfomycin (murA, glpT, uhpA, uhpB, uhpC, uhpT, uhpA, ptsI, cyaA, and crp) were amplified by PCR and then sequenced for the six FOS-resistant clinical isolates. FOS-susceptible E. coli strain BW25113 was used as a control for PCR and sequencing. Primers used in this study were those from our previous work (23).

Statistics.

All statistical analyses were carried out using R software (Free Software Foundation's GNU General Public License), specifically the R commander package (R, version 3.3.3). Differences in maximal growth rates were determined using the Mann-Whitney nonparametric method. P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Plan Nacional de I+D+i 2013-2016 and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Subdirección General de Redes y Centros de Investigación Cooperativa, Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (grants REIPI RD12/0015 and REIPI RD16/0016/0009)—cofinanced by the European Development Regional Fund “A Way to Achieve Europe”—by Operative Program Intelligent Growth 2014-2020 grants FIS PI13/00063 and PI13/01885 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, and by grant PI-0044-2013 from the Consejería de Salud, Junta de Andalucía. G.M.-G. was supported by a Río Hortega research contract from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. F.D.-P. was supported by a VPPI-US fellowship from the University of Sevilla.

REFERENCES

- 1.Castañeda-García A, Blázquez J, Rodríguez-Rojas A. 2013. Molecular mechanisms and clinical impact of acquired and intrinsic fosfomycin resistance. Antibiotics 2:217–236. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics2020217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendlin D, Stapley EO, Jackson M, Wallick H, Miller AK, Wolf FJ, Miller TW, Chaiet L, Kahan FM, Foltz EL, Woodruff HB, Mata JM, Hernandez S, Mochales S. 1969. Phosphonomycin, a new antibiotic produced by strains of streptomyces. Science 166:122–123. doi: 10.1126/science.166.3901.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keating GM. 2013. Fosfomycin trometamol: a review of its use as a single-dose oral treatment for patients with acute lower urinary tract infections and pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Drugs 73:1951–1966. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0143-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michalopoulos A, Virtzili S, Rafailidis P, Chalevelakis G, Damala M, Falagas ME. 2010. Intravenous fosfomycin for the treatment of nosocomial infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in critically ill patients: a prospective evaluation. Clin Microbiol Infect 16:184–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falagas ME, Vouloumanou EK, Samonis G, Vardakas KZ. 2016. Fosfomycin. Clin Microbiol Rev 29:321–347. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00068-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel SS, Balfour JA, Bryson HM. 1997. Fosfomycin tromethamine. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy as a single-dose oral treatment for acute uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections. Drugs 53:637–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matzi V, Lindenmann J, Porubsky C, Kugler SA, Maier A, Dittrich P, Smolle-Jüttner FM, Joukhadar C. 2010. Extracellular concentrations of fosfomycin in lung tissue of septic patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:995–998. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schintler MV, Traunmüller F, Metzler J, Kreuzwirt G, Spendel S, Mauric O, Popovic M, Scharnagl E, Joukhadar C. 2009. High fosfomycin concentrations in bone and peripheral soft tissue in diabetic patients presenting with bacterial foot infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 64:574–578. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfausler B, Spiss H, Dittrich P, Zeitlinger M, Schmutzhard E, Joukhadar C. 2004. Concentrations of fosfomycin in the cerebrospinal fluid of neurointensive care patients with ventriculostomy-associated ventriculitis. J Antimicrob Chemother 53:848–852. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirt SW, Alken A, Müller H, Haverich A, Vömel W. 1990. Perioperative preventive antibiotic treatment with fosfomycin in heart surgery: serum kinetics in extracorporeal circulation and determination of concentration in heart valve tissue. Z Kardiol 79:615–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Neill. 2016. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. Wellcome Trust and Her Majesty's Government; http://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160525_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguilar-Company J, Los-Arcos I, Pigrau C, Rodríguez-Pardo D, Larrosa MN, Rodríguez-Garrido V, Sihuay-Diburga D, Almirante B. 2016. Potential use of fosfomycin-tromethamine for treatment of recurrent Campylobacter species enteritis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:4398–4400. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00447-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grayson ML, Macesic N, Trevillyan J, Ellis AG, Zeglinski PT, Hewitt NH, Gardiner BJ, Frauman AG. 2015. Fosfomycin for treatment of prostatitis: new tricks for old dogs. Clin Infect Dis 61:1141–1143. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vergara-López S, Domínguez MC, Conejo MC, Pascual Á, Rodríguez-Baño J. 2015. Prolonged treatment with large doses of fosfomycin plus vancomycin and amikacin in a case of bacteraemia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis and IMP-8 metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella oxytoca. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:313–315. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simkins J, Fan J, Camargo JF, Aragon L, Frederick C. 2015. Intravenous fosfomycin treatment for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in the United States. Ann Pharmacother 49:1177–1178. doi: 10.1177/1060028015598326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foxman B. 2010. The epidemiology of urinary tract infection. Nat Rev Urol 7:653–660. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foxman B. 2002. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Am J Med 113(Suppl 1A):5S–13S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahan FM, Kahan JS, Cassidy PJ, Kropp H. 1974. The mechanism of action of fosfomycin (phosphonomycin). Ann N Y Acad Sci 235:364–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb43277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silver LL. 2003. Novel inhibitors of bacterial cell wall synthesis. Curr Opin Microbiol 6:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuruoka T, Miyata A, Yamada Y. 1978. Two kinds of mutants defective in multiple carbohydrate utilization isolated from in vitro fosfomycin-resistant strains of Escherichia coli K-12. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 31:192–201. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.31.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alper MD, Ames BN. 1978. Transport of antibiotics and metabolite analogs by systems under cyclic AMP control: positive selection of Salmonella typhimurium cya and crp mutants. J Bacteriol 133:149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Venkateswaran PS, Wu HC. 1972. Isolation and characterization of a phosphonomycin-resistant mutant of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 110:935–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Couce A, Briales A, Rodríguez-Rojas A, Costas C, Pascual A, Blázquez J. 2012. Genomewide overexpression screen for fosfomycin resistance in Escherichia coli: MurA confers clinical resistance at low fitness cost. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2767–2769. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06122-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herring CD, Blattner FR. 2004. Conditional lethal amber mutations in essential Escherichia coli genes. J Bacteriol 186:2673–2681. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2673-2681.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballestero-Téllez M, Docobo-Pérez F, Portillo-Calderón I, Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Racero L, Ramos-Guelfo MS, Blázquez J, Rodríguez-Baño J, Pascual A. 2017. Molecular insights into fosfomycin resistance in Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:1303–1309. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baquero F. 2001. Low-level antibacterial resistance: a gateway to clinical resistance. Drug Resist Updat 4:93–105. doi: 10.1054/drup.2001.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorlozano A, Jimenez-Pacheco A, de Dios Luna del Castillo J, Sampedro A, Martinez-Brocal A, Miranda-Casas C, Navarro-Marí JM, Gutiérrez-Fernández J. 2014. Evolution of the resistance to antibiotics of bacteria involved in urinary tract infections: a 7-year surveillance study. Am J Infect Control 42:1033–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahlmeter G, Poulsen HO. 2012. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Escherichia coli from community-acquired urinary tract infections in Europe: the ECO·SENS study revisited. Int J Antimicrob Agents 39:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchese A, Gualco L, Debbia EA, Schito GC, Schito AM. 2003. In vitro activity of fosfomycin against gram-negative urinary pathogens and the biological cost of fosfomycin resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents 22(Suppl 2):S53–S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilsson AI, Berg OG, Aspevall O, Kahlmeter G, Andersson DI. 2003. Biological costs and mechanisms of fosfomycin resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:2850–2858. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2850-2858.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon DM, Riley MA. 1992. A theoretical and experimental analysis of bacterial growth in the bladder. Mol Microbiol 6:555–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahata S, Ida T, Hiraishi T, Sakakibara S, Maebashi K, Terada S, Muratani T, Matsumoto T, Nakahama C, Tomono K. 2010. Molecular mechanisms of fosfomycin resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35:333–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohkoshi Y, Sato T, Suzuki Y, Yamamoto S, Shiraishi T, Ogasawara N, Yokota S. 2017. Mechanism of reduced susceptibility to fosfomycin in Escherichia coli clinical isolates. Biomed Res Int 2017:5470241. doi: 10.1155/2017/5470241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersson DI, Hughes D. 2010. Antibiotic resistance and its cost: is it possible to reverse resistance? Nat Rev Microbiol 8:260–271. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martín-Gutiérrez G, Rodríguez-Beltrán J, Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Costas C, Aznar J, Pascual Á, Blázquez J. 2016. Urinary tract physiological conditions promote ciprofloxacin resistance in low-level-quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:4252–4258. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00602-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martín-Gutiérrez G, Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Pascual Á, Rodríguez-Beltrán J, Blázquez J. 2017. Plasmidic qnr genes confer clinical resistance to ciprofloxacin under urinary tract physiological conditions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02615-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02615-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giannakopoulos X, Evangelou A, Kalfakakou V, Grammeniatis E, Papandropoulos I, Charalambopoulos K. 1997. Human bladder urine oxygen content: implications for urinary tract diseases. Int Urol Nephrol 29:393–401. doi: 10.1007/BF02551103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballestero-Téllez M, Docobo-Pérez F, Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Conejo MC, Ramos-Guelfo MS, Blázquez J, Rodríguez-Baño J, Pascual A. 2017. Role of inoculum and mutant frequency on fosfomycin MIC discrepancies by agar dilution and broth microdilution methods in Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Infect 23:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pietsch F. 2015. Evolution of antibiotic resistance. PhD thesis Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:862238. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jorgensen J, Turnidge J. 2015. Susceptibility test methods: dilution and disk diffusion methods*, p 1253–1273. In Jorgensen J, Pfaller M, Carroll K, Funke G, Landry M, Richter S, Warnock D (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, 11th ed ASM Press, Washington, DC. doi: 10.1128/9781555817381.ch71. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burian A, Erdogan Z, Jandrisits C, Zeitlinger M. 2012. Impact of pH on activity of trimethoprim, fosfomycin, amikacin, colistin and ertapenem in human urine. Pharmacology 90:281–287. doi: 10.1159/000342423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erdogan-Yildirim Z, Burian A, Manafi M, Zeitlinger M. 2011. Impact of pH on bacterial growth and activity of recent fluoroquinolones in pooled urine. Res Microbiol 162:249–252. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fedrigo NH, Mazucheli J, Albiero J, Shinohara DR, Lodi FG, Machado ACDS, Sy SKB, Tognim MCB. 2017. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of fosfomycin against Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. from urinary tract infections and the influence of pH on fosfomycin activities. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02498-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02498-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kurabayashi K, Tanimoto K, Fueki S, Tomita H, Hirakawa H. 2015. Elevated expression of GlpT and UhpT via FNR activation contributes to increased fosfomycin susceptibility in Escherichia coli under anaerobic conditions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6352–6360. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01176-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bergogne-Bérézin E, Muller-Serieys C, Joly-Guillou ML, Dronne N. 1987. Trometamol-fosfomycin (Monuril) bioavailability and food-drug interaction. Eur Urol 13(Suppl 1):S64–S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frassetto L, Kohlstadt I. 2011. Treatment and prevention of kidney stones: an update. Am Fam Physician 84:1234–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yü TF. 1977. Some unusual features of gouty arthritis in females. Semin Arthritis Rheum 6:247–255. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(77)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guedes-Marques M, Silva C, Ferreira E, Maia P, Carreira A, Campos M. 2014. Gitelman syndrome with hiponatremia, a rare presentation. Nefrologia 34:266–268. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2013.Nov.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.EUCAST. 2016. Clinical breakpoints. http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints.

- 50.Michon A, Allou N, Chau F, Podglajen I, Fantin B, Cambau E. 2011. Plasmidic qnrA3 enhances Escherichia coli fitness in absence of antibiotic exposure. PLoS One 6:e24552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]