ABSTRACT

In most bacteria, the essential targets of β-lactam antibiotics are the d,d-transpeptidases that catalyze the last step of peptidoglycan polymerization by forming 4→3 cross-links. The peptidoglycan of Clostridium difficile is unusual since it mainly contains 3→3 cross-links generated by l,d-transpeptidases. To gain insight into the characteristics of C. difficile peptidoglycan cross-linking enzymes, we purified the three putative C. difficile l,d-transpeptidase paralogues LdtCd1, LdtCd2, and LdtCd3, which were previously identified by sequence analysis. The catalytic activities of the three proteins were assayed with a disaccharide-tetrapeptide purified from the C. difficile cell wall. LdtCd2 and LdtCd3 catalyzed the formation of 3→3 cross-links (l,d-transpeptidase activity), the hydrolysis of the C-terminal d-Ala residue of the disaccharide-tetrapeptide substrate (l,d-carboxypeptidase activity), and the exchange of the C-terminal d-Ala for d-Met. LdtCd1 displayed only l,d-carboxypeptidase activity. Mass spectrometry analyses indicated that LdtCd1 and LdtCd2 were acylated by β-lactams belonging to the carbapenem (imipenem, meropenem, and ertapenem), cephalosporin (ceftriaxone), and penicillin (ampicillin) classes. Acylation of LdtCd3 by these β-lactams was not detected. The acylation efficacy of LdtCd1 and LdtCd2 was higher for the carbapenems (480 to 6,600 M−1 s−1) than for ampicillin and ceftriaxone (3.9 to 82 M−1 s−1). In contrast, the efficacy of the hydrolysis of β-lactams by LdtCd1 and LdtCd2 was higher for ampicillin and ceftriaxone than for imipenem. These observations indicate that LdtCd1 and LdtCd2 are inactivated only by β-lactams of the carbapenem class due to a combination of rapid acylation and the stability of the resulting covalent adducts.

KEYWORDS: β-lactam; carbapenems; Clostridium difficile; l,d-transpeptidases; peptidoglycan

INTRODUCTION

Clostridium difficile is an anaerobic Gram-positive spore-forming bacterium responsible for 15 to 25% of postantibiotic diarrhea and more than 95% of pseudomembranous colitis cases (1). It is the first cause of nosocomial infectious diarrhea in adults (2). Dysbiosis due to antibiotics is thought to be the main cause of C. difficile-associated diseases (3). Antibiotics that promote these infections are active against C. difficile, highlighting the likely importance of spore formation. The recent evolution of C. difficile-associated diseases is worrisome due to the emergence and rapid spread of the virulent C. difficile clone 027 (4).

Metronidazole per os is the first-line treatment for nonsevere infections (5). The emergence of isolates with intermediate susceptibility may compromise the efficacy of metronidazole (6). Vancomycin per os is used in severe infections (5), but this treatment is associated with a risk of emergence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. A new antibiotic, fidaxomicin, is recommended for recurrent infections (5), but this drug has not been evaluated for severe infections (7, 8). Fidaxomicin has not been used for a sufficient time period to evaluate the risk of emergence of resistance, and therapeutic options remain limited for C. difficile-associated diseases.

The structure of the cell wall peptidoglycan is unusual in C. difficile, since the majority (70%) of the cross-links are of the 3→3 type formed by l,d-transpeptidases (LDTs) (Fig. 1A) (9). This feature is shared only with mycobacteria (10, 11), as the peptidoglycans from all other bacterial species that have been studied mainly or exclusively contain 4→3 cross-links formed by the d,d-transpeptidase activity of classical penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) (12) (Fig. 1B). LDTs and PBPs are structurally unrelated, harbor different catalytic residues (Cys and Ser, respectively), and use distinct acyl donors for the cross-linking reaction (tetrapeptide and pentapeptide, respectively) (13–15). PBPs are potentially inhibited by all classes of β-lactams, whereas LDTs are inhibited only by carbapenems (16, 17).

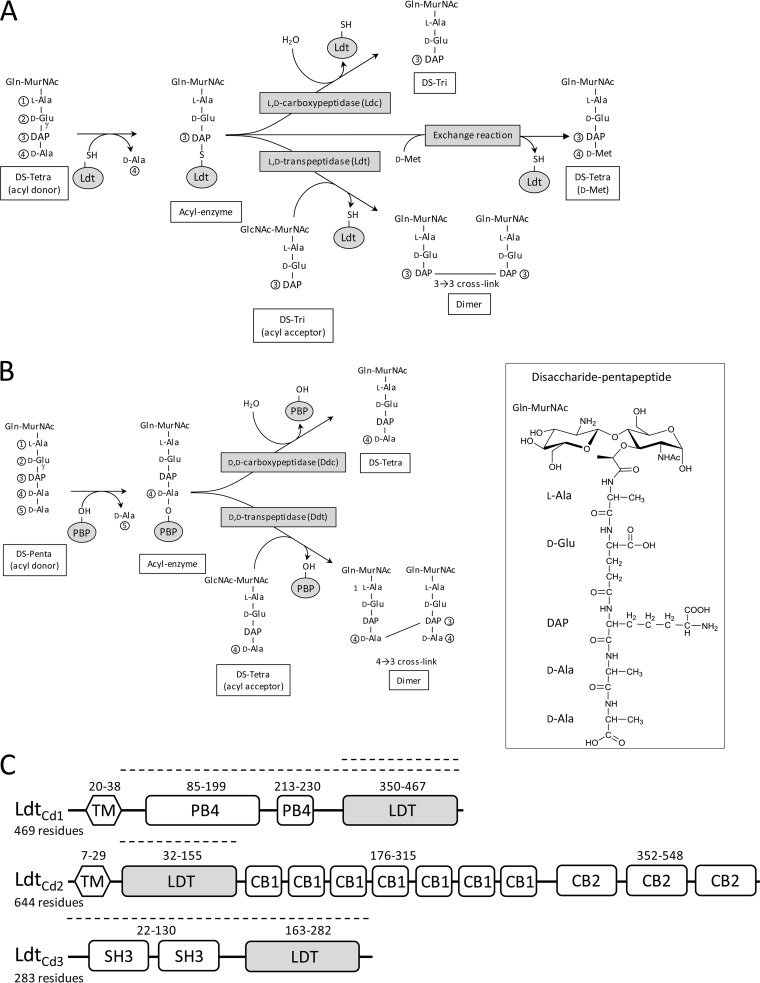

FIG 1.

Peptidoglycan cross-linking in C. difficile. The inset shows the developed structure of the disaccharide (DS)-pentapeptide subunit of C. difficile. (A) Reactions catalyzed by l,d-transpeptidases (Ldt). (B) Reactions catalyzed by penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). (C) Domain compositions of LdtCd1, LdtCd2, and LdtCd3. Numbers refer to the boundaries of the domains. Dashed lines indicate the portions of LdtCd1 (residues 39 to 469 and 350 to 469), LdtCd2 (residues 30 to 156), and LdtCd3 (residues 1 to 256) present in recombinant proteins produced in E. coli. These portions of the proteins comprise (i) the entire protein without the putative transmembrane segment or the catalytic l,d-transpeptidase domain for LdtCd1, (ii) the catalytic domain for LdtCd2, and (iii) the entire protein for LdtCd3. The recombinant proteins contained an additional vector-encoded N-terminal 6×His tag followed by a TEV cleavage site (MGSSHHHHHHSSGENLYFQGHM). Domain identification is based on sequence similarities in the absence of functional data. CB1, cell wall-binding type 1 domain; Ldt, catalytic l,d-transpeptidase domain; PB4, protein-binding pattern type 4; SH3, bacterial domain SH3; TM, transmembrane segment.

The genome of C. difficile encodes three l,d-transpeptidase paralogues, designated LdtCd1, LdtCd2, and LdtCd3 (Fig. 1C), potentially involved in the formation of 3→3 cross-links (70%), and four high-molecular-weight PBPs, potentially involved in the formation of the remaining cross-links (4→3 type; 30%) (9). The inactivation of the ldtCd1 or ldtCd2 gene has been reported to result in a significant decrease in the abundance of 3→3 cross-links and in overall peptidoglycan reticulation, but the growth rate was not affected. These observations indicate that LdtCd1 and LdtCd2 have redundant cross-linking activities (9). In the presence of ampicillin, the relative proportions of 3→3 cross-links increased as expected from the lack of inhibition of LDTs by β-lactams belonging to the penam (penicillin) class (9).

To date, the characteristics of C. difficile LDTs have been inferred only indirectly from studies of mutants deficient in the production of LdtCd1 or LdtCd2 and from the impact of ampicillin on the relative abundances of 3→3 and 4→3 cross-links (9). To gain insight into the catalytic properties of LDT paralogues from C. difficile, we purified LdtCd1, LdtCd2, and LdtCd3 and determined their peptidoglycan cross-linking activity. We also investigated the inhibition of the three LDTs by β-lactams.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Purification of soluble LdtCd1, LdtCd2, and LdtCd3.

Two forms of LdtCd1 were produced in Escherichia coli and purified, which comprised the entire protein without the N-terminal transmembrane segment or the catalytic domain only (Fig. 1). The catalytic domain was used for mass spectrometry analyses of protein–β-lactam adducts, while the larger form of the protein was used for transpeptidation, stopped-flow spectrofluorimetry, and spectrophotometry assays due to its higher solubility. For LdtCd2, all experiments were performed with the catalytic domain. The catalytic domain of LdtCd3 was not soluble, but this issue was solved by purifying the entire protein, which does not harbor any putative transmembrane segment, in contrast to LdtCd1 and LdtCd2.

Transpeptidase and carboxypeptidase activities of LdtCd1, LdtCd2, and LdtCd3.

The activities of the three recombinant LDTs were assayed with a disaccharide-tetrapeptide substrate purified from the cell wall peptidoglycan of C. difficile (Fig. 1). Purified LDTs and the disaccharide-tetrapeptide were incubated for 3 h, and the formation of the products was assayed by mass spectrometry. Incubation of LdtCd2 and LdtCd3 with the disaccharide-tetrapeptide substrate resulted in the formation of a dimer and a disaccharide-tripeptide, indicating that these enzymes display both l,d-transpeptidase (LDT) and l,d-carboxypeptidase (ld-CPase) activities (Fig. 1A and Table 1). The dimer contained a 3→3 cross-link connecting two disaccharide-tripeptides (Table 1). This may imply two mutually nonexclusive reaction schemes involving both the LDT and ld-CPase activities of LdtCd2 and LdtCd3. For the first reaction scheme, the disaccharide-tripeptide generated by the ld-CPase activity is used as the acyl acceptor substrate to generate the dimer (as depicted in Fig. 1A). For the second reaction scheme, the cross-linking reaction involves an acyl acceptor containing a tetrapeptide stem, and d-Ala4 is cleaved from the dimer by the ld-CPase activity.

TABLE 1.

Monoisotopic masses of l,d-transpeptidase reaction products

| LDT | Monoisotopic mass of reaction product (Da)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trib (calculated mass, 828.36 Da) | Dimerb (calculated mass, 1,638.71 Da) | Tetra(d-Met)c (calculated mass, 959.40 Da) | |

| LdtCd1 | 828.37 | ND | ND |

| LdtCd2 | 828.36 | 1,638.71 | 959.38 |

| LdtCd3 | 828.37 | 1,638.66 | 959.40 |

ND, not detected; Tri, GlcN–MurNAc–l-Ala–γ-d-Glu–DAP; Tetra(d-Met), GlcN–MurNAc–l-Ala–γ-d-Glu–DAP–d-Met.

LDTs were incubated with the disaccharide-tetrapeptide GlcN–MurNAc–l-Ala–γ-d-Glu–DAP–d-Ala, leading to the formation of a disaccharide-tripeptide (l,d-carboxypeptidase activity) and of a dimer containing a 3→3 cross-link (l,d-transpeptidase activity).

LDTs were incubated with the disaccharide-tetrapeptide and d-Met, leading to the exchange of d-Ala4 for d-Met.

The formation of an acyl-enzyme is a common intermediary for the LDT and ld-CPase activities (Fig. 1A). Previous analyses of LDT from Enterococcus faecium (Ldtfm) showed that the acyl-enzyme may also react with free amino acids of the d-configuration, such as d-Met, or glycine (15). The net result is the replacement of d-Ala4 by d-Met or Gly at the extremity of a tetrapeptide stem (exchange reaction) (Fig. 1A). Both LdtCd2 and LdtCd3 catalyzed this reaction (Table 1).

The remaining l,d-transpeptidase, LdtCd1, did not catalyze the formation of 3→3 cross-links or the exchange of d-Ala4 for d-Met (Table 1). However, LdtCd1 was purified in an active form since it cleaved the diaminopimelyl3–d-alanine4 (DAP3–d-Ala4) bond to form a disaccharide-tripeptide. Thus, the disaccharide-tetrapeptide was used as an acyl donor but not as an acyl acceptor by LdtCd1.

Acyl-enzymes formed by LdtCd1, LdtCd2, and LdtCd3 with β-lactams.

LdtCd3 did not form any covalent adduct with the five β-lactams that were tested (data not shown). LdtCd3 was purified in a catalytically active form since it catalyzed cross-link formation (see above) (Table 1). In Mycobacterium tuberculosis, one of the five l,d-transpeptidase paralogues (LdtMt5) similarly catalyzes the formation of peptidoglycan dimers in vitro in the absence of detectable acylation by β-lactams (18).

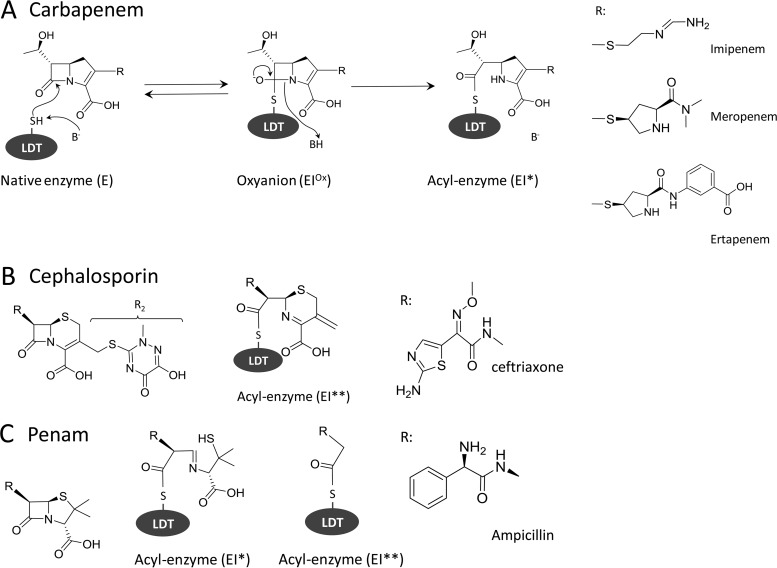

For LdtCd1 and LdtCd2, mass spectrometry analysis revealed the formation of acyl-enzymes for representatives of three classes of β-lactams (Table 2). For carbapenems, the mass of the acyl-enzymes (EI*) corresponded to the mass of the proteins plus the mass of the β-lactam, indicating the presence of the entire drugs in the covalent adducts (Fig. 2). Acylation of the l,d-transpeptidases by the cephalosporin ceftriaxone led to the loss of the R2 side chain (acyl-enzyme EI**). The acyl-enzyme containing the complete drug (EI*) was not detected, suggesting a concerted mechanism involving the simultaneous acylation and loss of the R2 side chain, as previously described (17, 19). Incubation of LDTs with ampicillin led to the formation of two acyl-enzymes containing the complete drug (EI*) or a drug fragment following the cleavage of the C5—C6 bond of the β-lactam ring (EI**). This unexpected cleavage of a carbon-carbon bond was previously reported for l,d-transpeptidases (17) and a d,d-carboxypeptidase (20).

TABLE 2.

Masses of l,d-transpeptidases and of acyl-enzymes formed with various β-lactamsa

| LDT and β-lactam (mass [Da]) | Enzyme or acyl-enzyme (expected mass increase [Da]) | Avg mass (Da) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated | Observed | ||

| LdtCd1 | E (NA) | 15,753.5 | 15,753.6 |

| Imipenem (299.3) | EI* (299.3) | 16,052.8 | 16,053.0 |

| Meropenem (383.5) | EI* (383.5) | 16,137.0 | 16,137.3 |

| Ertapenem (475.5) | EI* (475.5) | 16,229.0 | 16,229.2 |

| Ceftriaxone (554.6) | EI** (395.4) | 16,148.9 | 16,148.9 |

| Ampicillin (349.4) | EI* (349.4) | 16,102.9 | ND |

| Ampicillin (349.4) | EI** (190.2) | 15,943.7 | 15,943.9 |

| LdtCd2 | E (NA) | 16,430.5 | 16,430.7 |

| Imipenem (299.3) | EI* (299.3) | 16,729.8 | 16,730.3 |

| Meropenem (383.5) | EI* (383.5) | 16,814.0 | 16,814.3 |

| Ertapenem (475.5) | EI* (475.5) | 16,906.0 | 16,906.3 |

| Ceftriaxone (554.6) | EI** (395.4) | 16,825.9 | 16,826.5 |

| Ampicillin (349.4) | EI* (349.4) | 16,779.9 | 16,780.0 |

| Ampicillin (349.4) | EI** (190.2) | 16,620.7 | 16,620.6 |

All values are average masses in daltons. E designates the native form of the enzymes observed in the absence of any antibiotic. EI* and EI** designate two acyl-enzymes formed with the same β-lactam (ampicillin or ceftriaxone) due to the cleavage of the drugs after the acylation reaction. Acylation was partial for ceftriaxone and ampicillin but complete for carbapenems. ND, not detected; NA, not applicable.

FIG 2.

Acyl-enzymes formed by C. difficile l,d-transpeptidases with β-lactams. (A) Two-step reaction leading to irreversible inactivation of an LDT by a carbapenem. (B and C) Acyl-enzymes formed with a cephalosporin and a penam, respectively.

Kinetics of acylation of LdtCd1 and LdtCd2 by β-lactams.

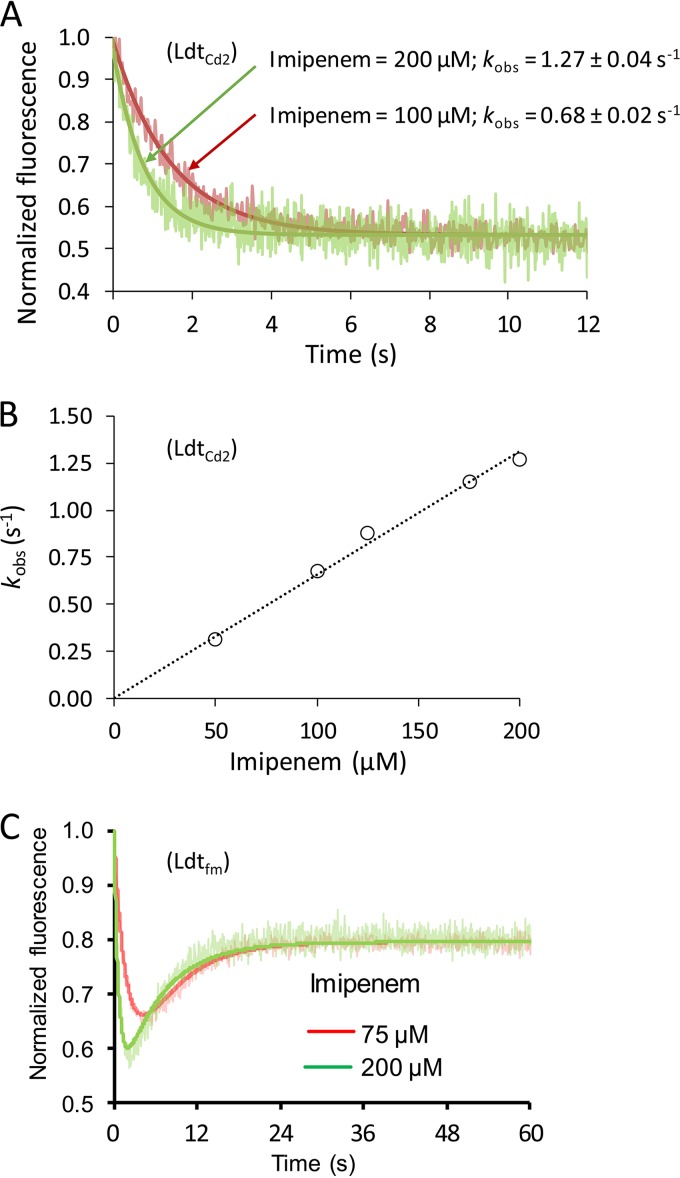

Stopped-flow spectrofluorimetry was used to compare the efficacies of inactivation of the l,d-transpeptidases by β-lactams (Table 3 and Fig. 3). This method was developed for Ldtfm from E. faecium (21) and applied to the characterization of the l,d-transpeptidases from M. tuberculosis (18). The fluorescence kinetics obtained with these enzymes is biphasic (see Fig. 3C for the example of Ldtfm). In the first phase, the fluorescence of the Trp residues of the enzymes is quenched due to reversible formation of an oxyanion. In the second phase, the fluorescence intensity increases due to the formation of the acyl-enzyme, to the detriment of the oxyanion. The biphasic nature of the fluorescence kinetics is accounted for by the large variations in the fluorescences of the three forms of the enzyme, which are maximum for the apo form (E), minimum for the oxyanion (EIox), and intermediate for the acyl-enzyme (EI*). Surprisingly, monophasic kinetics were observed for the inactivation of C. difficile LdtCd1 and LdtCd2 by carbapenems, as exemplified in Fig. 3A by the data obtained for the inactivation of LdtCd2 by imipenem. This monophasic behavior may be accounted for by the lack of accumulation of the oxyanion or by the absence of a significant difference between the fluorescence quantum yields of the oxyanion and of the acyl-enzyme (21). Since this monophasic behavior prevented the independent evaluation of the kinetic parameters for the formation of the oxyanion and of the acyl-enzyme, we determined the overall efficacy of inactivation of the l,d-transpeptidases by carbapenems (Fig. 3B and Table 3), as previously described (17). The efficacy of acylation of LdtCd1 and LdtCd2 by ampicillin and ceftriaxone was ca. 10- to 50-fold lower than the efficacy of acylation of these l,d-transpeptidases by carbapenems. Overall, the efficacies of acylation of the l,d-transpeptidases from C. difficile (this work), M. tuberculosis (18), and E. faecium (17) were of the same orders of magnitude, and all enzymes displayed specificity for carbapenems. Incubation of LdtCd3 with carbapenems did not result in variations in fluorescence intensity (data not shown), in agreement with the absence of detection of any covalent adduct by mass spectrometry (see above).

TABLE 3.

Efficacies of acylation of C. difficile l,d-transpeptidases by β-lactams

| β-Lactam | Mean acylation efficacy (M−1 s−1) ± SEa |

|

|---|---|---|

| LdtCd1 | LdtCd2 | |

| Ampicillin | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 66 ± 3 |

| Ceftriaxone | 82 ± 20 | 40 ± 1 |

| Imipenem | 3,100 ± 400 | 6,600 ± 100 |

| Meropenem | 1,100 ± 400 | 480 ± 20 |

| Ertapenem | 3,200 ± 500 | 1,030 ± 20 |

Values are the means ± standard errors from the linear regression for the kinetic parameter k2/Kapp.

FIG 3.

Kinetics of acylation of C. difficile l,d-transpeptidase LdtCd2 by imipenem. (A) Examples of stopped-flow fluorescence kinetics obtained with LdtCd2 (10 μM) and two concentrations of imipenem (100 and 200 μM). The rate constant kobs was determined by fitting the data to exponential decay. (B) The rate constant kobs increased linearly with the concentration of imipenem. The slope provided an estimate of the efficacy of enzyme acylation (6,600 ± 100 M−1 s−1). (C) Examples of stopped-flow fluorescence kinetics obtained with Ldtfm (10 μM) and two concentrations of imipenem (17).

Kinetics of β-lactam hydrolysis by LdtCd1 and LdtCd2.

The turnovers for the hydrolysis of β-lactams by the l,d-transpeptidases of C. difficile (Table 4) showed that the covalent adducts formed by the acylation of these enzymes by carbapenems were stable. Half-lives of >150 min were deduced from the observed turnover for the hydrolysis of the carbapenems, which were <8 × 10−5 s−1 (see reference 17 for the calculation). The acyl-enzyme formed with ampicillin and LdtCd2 was the least stable, as previously described (17), with a half-life of 2.0 min. This value indicates that LdtCd2 is poorly inhibited by ampicillin, although the low turnover for hydrolysis implies that the enzyme is unlikely to contribute to resistance by acting as a β-lactamase. In comparison to the l,d-transpeptidases from E. faecium and M. tuberculosis (17, 18), the turnovers for the hydrolysis of β-lactams by C. difficile l,d-transpeptidases did not reveal any striking difference, since the stability of the acyl-enzyme was highest for carbapenems, lowest for penams (penicillin), and intermediary for cephems (cephalosporins).

TABLE 4.

Hydrolysis of β-lactams by C. difficile l,d-transpeptidases

| β-Lactam | Mean hydrolysis turnover (106) (s−1) ± SEa |

|

|---|---|---|

| LdtCd1 | LdtCd2 | |

| Ampicillin | <1,000 | 5,800 ± 400 |

| Ceftriaxone | 160 ± 10 | 180 ± 15 |

| Imipenem | <180 | <180 |

| Meropenem | 30 ± 5 | 48 ± 7 |

| Ertapenem | 40 ± 3 | 79 ± 13 |

Values are means ± standard errors from the linear regression for turnover rates.

Conclusions.

Peltier et al. (9) previously showed that the peptidoglycan of C. difficile contains an unusually high (73%) content of 3→3 cross-links in comparison to all other firmicutes that have been submitted to peptidoglycan structure analysis, typically <10% or 0% depending upon the presence (e.g., E. faecium) or absence (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus) of genes encoding members of the LDT family in their genome (22). The deletion of the genes encoding LdtCd1 and LdtCd2, alone or in combination, was associated with a decrease in the proportion of muropeptide dimers containing 3→3 cross-links, from 41% for the wild-type strain to 19%, 26%, and 13%, respectively (9). This observation provided evidence that LdtCd1 and LdtCd2 form 3→3 cross-links in vivo (9). For unknown reasons, the proportion of 4→3 cross-links was also reduced albeit to a lesser extent (from 15% for the wild-type strain to 11%, 11%, and 12% for the deletion of ldtCd1, ldtCd2, and ldtCd1 plus ldtCd2, respectively) (9). Consequently, the deletions of ldtCd1, ldtCd2, and ldtCd1 plus ldtCd2 led to decreases in the proportions of dimers (from 57% for the wild-type strain to 30%, 37%, and 34%, respectively), with a moderate impact on the relative proportions of 3→3 cross-links among dimers, which were reduced from 73% for the wild-type strain to only 64%, 70%, and 66%, respectively (9). These observations indicate that the increased formation of 4→3 cross-links by the PBPs did not compensate for the absence of LdtCd1 and LdtCd2, resulting in a less cross-linked peptidoglycan.

The detection of 3→3 cross-links in the double mutant lacking LdtCd1 and LdtCd2 revealed the existence of a third l,d-transpeptidase in C. difficile (9). The corresponding gene was tentatively identified as CD3007, but attempts to inactivate it were unsuccessful (9). In the present study, purification of the product of CD3007 showed that this enzyme is indeed functional as a peptidoglycan cross-linking enzyme, and the corresponding protein was therefore designated LdtCd3. Together, the results obtained for the inactivation of the ldt genes by Peltier et al. (9) and by the characterization of purified enzymes in the present study clearly indicate that the three LDTs of C. difficile have redundant functions, at least partially, as observed for PBPs in most bacteria. However, there are discrepancies between the two approaches. In particular, the formation of 3→3 cross-links by purified LdtCd1 was not detected in vitro, although the deletion of the corresponding gene led to a reduction of the proportion of dimers containing 3→3 cross-links in the peptidoglycan layer. This may indicate that LdtCd1 does not catalyze the cross-linking reactions with substrates consisting of an isolated disaccharide-tetrapeptide peptidoglycan fragment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

The oligonucleotide primers used to amplify portions of the ldtCd1 and ldtCd2 genes and the entire ldtCd3 gene are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Each ldtCd gene was independently amplified with two sets of primers (A1 plus A2 and B1 plus B2). The A1-A2 and B1-B2 amplicons were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, mixed, denatured, and annealed. Since the extremities of the A1-A2 and B1-B2 amplicons differed by the presence of the additional bases TA and TCGA (underlined in the sequences in Table S1 in the supplemental material), one of the two putative heteroduplexes contained cohesive ends compatible with the cohesive ends generated by the restriction endonucleases NdeI (CA↓TATG) and XhoI (C↓TCGAG), respectively. The heteroduplexes were ligated with the vector pET-TEV digested by NdeI plus XhoI, and the sequence of the insert in the resulting recombinant plasmids was confirmed.

Production and purification of l,d-transpeptidases.

The vector pET-TEV (our laboratory collection) is a derivative of pET28a (Novagen) that confers resistance to kanamycin and enables the obtainment of translational fusions consisting of a polyhistidine tag followed by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site (MHHHHHHENLYFQGHM), as previously used for the production of recombinant l,d-transpeptidases (17). E. coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring the recombinant pET-TEV (17) derivatives encoding LdtCd1, LdtCd2, and LdtCd3 were grown in brain heart infusion broth (Difco) containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml) at 37°C until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.8. Isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (0.5 mM) was added, and incubation was continued for 18 h at 16°C. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation (5,200 × g at 4°C), resuspended in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.4) containing 300 mM NaCl (buffer A), and lysed by sonication. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (17,400 × g at 4°C). The clarified lysate was filtered, and LDTs were purified by nickel affinity chromatography (nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid [Ni-NTA] resin; Sigma-Aldrich) and size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 75 HL 26/60 column; GE Healthcare) in buffer A. LDTs were concentrated by ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter devices; Millipore) to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml and stored at −65°C in buffer A. LDTs were purified in the absence of a reducing agent, as previously described (e.g., see reference 18), as the active-site residue of this family of enzymes is not readily oxidized.

Peptidoglycan cross-linking assay.

The disaccharide-tetrapeptide used as the substrate (Fig. 1) was purified from the peptidoglycan of C. difficile strain CD630. Briefly, bacteria were grown in brain heart infusion broth at 35°C under anaerobic conditions during 48 h without stirring. Peptidoglycan was extracted by the boiling-SDS procedure, treated with pronase and trypsin, and digested with mutanolysin and lysozyme (23). The resulting muropeptides (disaccharide peptides) were purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (rpHPLC) (23), the disaccharide-tetrapeptide was identified by mass spectrometry (23), and the concentration was determined by amino acid analysis after acid hydrolysis (24).

The synthesis of peptidoglycan cross-links by LDTs (10 μM) was determined by using 10 μl of 15 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 100 μM disaccharide-tetrapeptide. Incubation was performed at 37°C for 3 h. The exchange assay was performed under the same conditions in the presence of d-Met (1 mM). The products of the reactions catalyzed by the LDTs were identified by electrospray mass spectrometry in the positive mode (Qstar Pulsar I; Applied Biosystems), as previously described (23).

Mass spectrometry analyses of l,d-transpeptidase acylation by β-lactams.

l,d-Transpeptidases (10 μM) were incubated with β-lactams (100 μM) in a volume of 5 μl for 60 min at 20°C in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). The reaction mixture was injected into the mass spectrometer (Qstar Pulsar I; Applied Biosystems) at a flow rate of 0.05 ml/min (50% acetonitrile, 49.5% water, and 0.5% formic acid [per volume]). Spectra were acquired in the positive mode, as previously described (16).

Kinetics of l,d-transpeptidase inactivation by β-lactams.

Fluorescence data were acquired with a stopped-flow apparatus (RX-2000; Applied Biophysics) coupled to a spectrofluorometer (Cary Eclipse; Varian) in 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.0) at 10°C (17, 21). Hydrolysis of β-lactams by the LDTs was determined by spectrophotometry in sodium phosphate buffer (100 mM; pH 6.0) at 20°C in a Cary 100 spectrophotometer (Varian) (17, 21). The variations in the molar extinction coefficients resulting from the opening of the β-lactam ring were previously determined for carbapenems (−7,100 M−1 cm−1 at 299 nm), ceftriaxone (−9,600 M−1 cm−1 at 265 nm), and ampicillin (−700 M−1 cm−1 at 240 nm) (17).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Dubost and A. Marie for technical assistance in the collection of mass spectra (Bio-organic Mass Spectrometry Technical Platform, Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle).

L.S. and Z.E. were supported by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (DEA20150633341 and ECO20160736080, respectively).

We have no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01607-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbut F, Petit JC. 2001. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile-associated infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 7:405–410. doi: 10.1046/j.1198-743x.2001.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati GK, Dunn JR, Farley MM, Holzbauer SM, Meek JI, Phipps EC, Wilson LE, Winston LG, Cohen JA, Limbago BM, Fridkin SK, Gerding DN, McDonald LC. 2015. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 372:825–834. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ananthakrishnan AN. 2011. Clostridium difficile infection: epidemiology, risk factors and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 8:17–26. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuijper EJ, Barbut F, Brazier JS, Kleinkauf N, Eckmanns T, Lambert ML, Drudy D, Fitzpatrick F, Wiuff C, Brown DJ, Coia JE, Pituch H, Reichert P, Even J, Mossong J, Widmer AF, Olsen KE, Allerberger F, Notermans DW, Delmee M, Coignard B, Wilcox M, Patel B, Frei R, Nagy E, Bouza E, Marin M, Akerlund T, Virolainen-Julkunen A, Lyytikainen O, Kotila S, Ingebretsen A, Smyth B, Rooney P, Poxton IR, Monnet DL. 2008. Update of Clostridium difficile infection due to PCR ribotype 027 in Europe, 2008. Euro Surveill 13(31):pii=18942 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/ese.13.31.18942-en. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debast SB, Bauer MP, Kuijper EJ, European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2014. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 20(Suppl 2):S1–S26. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baines SD, O'Connor R, Freeman J, Fawley WN, Harmanus C, Mastrantonio P, Kuijper EJ, Wilcox MH. 2008. Emergence of reduced susceptibility to metronidazole in Clostridium difficile. J Antimicrob Chemother 62:1046–1052. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornely OA, Crook DW, Esposito R, Poirier A, Somero MS, Weiss K, Sears P, Gorbach S, OPT-80-004 Clinical Study Group. 2012. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 12:281–289. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, Weiss K, Lentnek A, Golan Y, Gorbach S, Sears P, Shue YK, OPT-80-003 Clinical Study Group. 2011. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 364:422–431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peltier J, Courtin P, El Meouche I, Lemee L, Chapot-Chartier MP, Pons JL. 2011. Clostridium difficile has an original peptidoglycan structure with a high level of N-acetylglucosamine deacetylation and mainly 3-3 cross-links. J Biol Chem 286:29053–29062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.259150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavollay M, Arthur M, Fourgeaud M, Dubost L, Marie A, Veziris N, Blanot D, Gutmann L, Mainardi JL. 2008. The peptidoglycan of stationary-phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis predominantly contains cross-links generated by l,d-transpeptidation. J Bacteriol 190:4360–4366. doi: 10.1128/JB.00239-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavollay M, Fourgeaud M, Herrmann JL, Dubost L, Marie A, Gutmann L, Arthur M, Mainardi JL. 2011. The peptidoglycan of Mycobacterium abscessus is predominantly cross-linked by l,d-transpeptidases. J Bacteriol 193:778–782. doi: 10.1128/JB.00606-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hugonnet JE, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Monton A, den Blaauwen T, Carbonnelle E, Veckerle C, Brun YV, van Nieuwenhze M, Bouchier C, Tu K, Rice LB, Arthur M. 2016. Factors essential for L,D-transpeptidase-mediated peptidoglycan cross-linking and beta-lactam resistance in Escherichia coli. eLife 5:e19469. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biarrotte-Sorin S, Hugonnet JE, Delfosse V, Mainardi JL, Gutmann L, Arthur M, Mayer C. 2006. Crystal structure of a novel beta-lactam-insensitive peptidoglycan transpeptidase. J Mol Biol 359:533–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mainardi JL, Morel V, Fourgeaud M, Cremniter J, Blanot D, Legrand R, Frehel C, Arthur M, Van Heijenoort J, Gutmann L. 2002. Balance between two transpeptidation mechanisms determines the expression of beta-lactam resistance in Enterococcus faecium. J Biol Chem 277:35801–35807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mainardi JL, Fourgeaud M, Hugonnet JE, Dubost L, Brouard JP, Ouazzani J, Rice LB, Gutmann L, Arthur M. 2005. A novel peptidoglycan cross-linking enzyme for a beta-lactam-resistant transpeptidation pathway. J Biol Chem 280:38146–38152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mainardi JL, Hugonnet JE, Rusconi F, Fourgeaud M, Dubost L, Moumi AN, Delfosse V, Mayer C, Gutmann L, Rice LB, Arthur M. 2007. Unexpected inhibition of peptidoglycan LD-transpeptidase from Enterococcus faecium by the beta-lactam imipenem. J Biol Chem 282:30414–30422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Triboulet S, Dubee V, Lecoq L, Bougault C, Mainardi JL, Rice LB, Etheve-Quelquejeu M, Gutmann L, Marie A, Dubost L, Hugonnet JE, Simorre JP, Arthur M. 2013. Kinetic features of L,D-transpeptidase inactivation critical for beta-lactam antibacterial activity. PLoS One 8:e67831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cordillot M, Dubee V, Triboulet S, Dubost L, Marie A, Hugonnet JE, Arthur M, Mainardi JL. 2013. In vitro cross-linking of Mycobacterium tuberculosis peptidoglycan by l,d-transpeptidases and inactivation of these enzymes by carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5940–5945. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01663-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubee V, Triboulet S, Mainardi JL, Etheve-Quelquejeu M, Gutmann L, Marie A, Dubost L, Hugonnet JE, Arthur M. 2012. Inactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis l,d-transpeptidase LdtMt1 by carbapenems and cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4189–4195. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00665-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marquet A, Frere JM, Ghuysen JM, Loffet A. 1979. Effects of nucleophiles on the breakdown of the benzylpenicilloyl-enzyme complex EI formed between benzylpenicillin and the exocellular DD-carboxypeptidase-transpeptidase of Streptomyces strain R61. Biochem J 177:909–916. doi: 10.1042/bj1770909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Triboulet S, Arthur M, Mainardi JL, Veckerle C, Dubee V, Nguekam-Nouri A, Gutmann L, Rice LB, Hugonnet JE. 2011. Inactivation kinetics of a new target of beta-lactam antibiotics. J Biol Chem 286:22777–22784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.239988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mainardi JL, Villet R, Bugg TD, Mayer C, Arthur M. 2008. Evolution of peptidoglycan biosynthesis under the selective pressure of antibiotics in Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:386–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arbeloa A, Hugonnet JE, Sentilhes AC, Josseaume N, Dubost L, Monsempes C, Blanot D, Brouard JP, Arthur M. 2004. Synthesis of mosaic peptidoglycan cross-bridges by hybrid peptidoglycan assembly pathways in gram-positive bacteria. J Biol Chem 279:41546–41556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auger G, van Heijenoort J, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Blanot D. 2003. A MurG assay which utilises a synthetic analogue of lipid I. FEMS Microbiol Lett 219:115–119. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(02)01203-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.