Abstract

Somali refugees are resettling in large numbers in the US, but little is known about the Somali Bantu, an ethnic minority within this population. Refugee youth mental health is linked to the functioning of the larger family unit. Understanding how the process of culturally adjusting to life after resettlement relates to family functioning can help identify what kind of interventions might strengthen families and lead to better mental health outcomes for youth. This paper seeks to address the following research questions: (1) How do different groups of Somali Bantu refugees describe their experiences of culturally adapting to life in the US?; and (2) How, if at all, do processes of cultural adaptation in a new country affect Somali Bantu family functioning? We conducted 14 focus groups with a total of 81 Somali Bantu refugees in New England. Authors analyzed focus groups using principles of thematic analysis to develop codes and an overarching theoretical model about the relationship between cultural adaptation, parent–child relationships, and family functioning. Views and expectations of parent–child relationships were compared between Somali Bantu youth and adults. Cultural negotiation was dependent upon broader sociocultural contexts in the United States that were most salient to the experience of the individual. Adult and youth participants had conflicting views around negotiating Somali Bantu culture, which often led to strained parent–child relationships. In contrast, youth sibling relationships were strengthened, as they turned to each other for support in navigating the process of cultural adaptation.

Keywords: Refugees, Youth mental health, Somali Bantu, Resettlement, Cultural negotiation, Family relationships

Introduction

Last year over 60 million people worldwide were displaced from their homes due to war and political violence [1]. In the past few years there has been an influx of refugees seeking asylum and resettlement in European countries, and recently plans were announced to dramatically increase the number resettled to the United States [2, 3]. Entire families often flee their home country together, with children and youth making up a large portion of the refugee population: of the more than 1 million first-time asylum seekers in the European Union in 2015, over a quarter (29%) were under the age of 18 [4]. In the United States, approximately 35% of all newly admitted refugees are children and youth [5].

Refugee families are often exposed to myriad adverse events and chronic stressors over the course of the refugee experience, ranging from pre-flight war traumas in their home country to third country resettlement challenges [6]. These experiences put refugee youth at elevated risk of psychiatric disorders compared to youth in the general population [7]. As such, there is increased recognition that the mental health and wellbeing of refugee youth should be a top priority for policy-makers, social service agencies, and individual mental health practitioners in countries of resettlement [8].

Cultural negotiation and an ecological approach

An ecological framework is needed to understand the experience of refugee youth and the challenges and opportunities they face during resettlement [9]. Bronfenbrenner’s model of human development posits that both risk and protective factors for child wellbeing exist throughout multiple spheres that influence child development. These range from self-contained settings such as the family (microsystem), interactions between these settings (mesosystem), through to interactions between a mesosystem and other settings that a child does not directly engage with (exosystem); societal and cultural factors (macrosystem) and the wider historical context (chronosystem) [10, 11].

This ecological framework and concept of multiple spheres of influence on child development is critical when examining how third country resettlement affects cultural identity construction and adaptation of refugee youth. Cultural identity, defined as an individual’s “cultural practices, values, and identification”, simultaneously influences and is influenced by each of these spheres [12]. Traditionally, the process of adapting to a new culture was defined as “acculturation,” a process of change for an individual that results from “contact between two or more cultural groups” [13]. This process can include acquiring language, values, behaviors and social norms of the new culture, shedding practices from the culture of origin, and developing strategies for maintaining practices of both cultural groups to achieve successful adaptation [13].

Recent work has developed a more nuanced understanding of the process of cultural adaptation, which moves beyond traditional views of acculturation in which individuals undergo a linear process of shedding their affiliation with their culture of origin and adopt values and practices in the receiving country [13]. Instead, individuals actively construct a sense of self that simultaneously includes multiple identities. Within the context of cultural adaptation, identity construction can be understood as a process that involves the development of an identity via “the intermingling, mixing, and moving of cultures” [14]. This process can be best described as “cultural negotiation,”— a strategy of identity construction that has no endpoint, and instead fluctuates over time depending upon developmental and environmental contexts. This concept of cultural negotiation has been used to describe the identity construction of other immigrant populations [15–17] and is preferable to the idea of “acculturation process,” which often fails to address how historical and contextual factors influence how, when, and to what extent individuals embrace different identities post resettlement [18].

Cultural negotiation and youth mental health

Stress related to cultural adaptation has been associated with poor mental health outcomes of refugee and immigrant youth, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [19–21]. One hypothesized mechanism by which cultural adaptation leads to psychosocial distress is family conflict. The acculturation-gap distress model of family functioning, developed in parallel to ideas about acculturation, proposes that tensions arise when family members adapt to their new environment in different ways and/or at different speeds from one another [22]. These intergenerational discrepancies in negotiation can impair youth functioning, increase distress, and contribute to parent–child conflict [23–25]. Although informed by less nuanced ideas about cultural adaptation, this model may still be relevant to understanding risk factors in refugee parent–child relationships. Proponents of the concept of cultural negotiation note that this process can unfold very differently based on the age of immigrants and refugees at the time of resettlement [12]. Thus, even though the concept of acculturation may be outdated, tensions between family members that arise from the underlying process of adaptation are still salient to understanding the refugee experience. It is, therefore, useful to reexamine the acculturation-gap distress model and hypothesized impact on family functioning through the more nuanced concept of cultural negotiation to improve our understanding of the relationship between cultural adaptation, family conflict, and youth mental health.

Somali Bantu refugees

“Somali Bantu” is a term for a number of groups of East Africans who comprise about 5% of the Somali population [26]. In Somalia, these groups experienced considerable marginalization [27]. Historically, the Somali Bantu were taken as slaves from other parts of Africa to work in Somalia [28]. The Bantu in Somalia were treated as second-class citizens and suffered significant discrimination, which contributed to widespread poverty, lack of access to schools, and limited land and political rights [27, 29]. Such rights violations intensified when the civil war broke out in 1991 and the Somali Bantu were exposed to high levels of war violence including killings, rape and forced military recruitment [28, 30]. To escape the brutality, many fled their homes to nearby refugee camps in Kenya, experiencing further subjugation while living in some of the most insecure sections of the refugee camps [28, 30].

In 1999, the United States (US) recognized the Somali Bantu as a persecuted minority group and moved to admit up to 12,000 Somali Bantu into the country [30]. Resettlement was delayed with the events of 9/11, and the majority came to the US between 2004 and 2006 [30]. Somali Bantu were granted refugee status, and are eligible for citizenship after having been in the country a minimum of 5 years; anecdotally the vast majority of Somali Bantu are now American citizens. Since their arrival, there has been limited research on Somali Bantus in the US. A few studies have focused on resettlement experiences and community needs [31, 32] and topics such as health education [33] and adjustment to the US health care system [34]. Some research has focused on Somali Bantu youth [35, 36] or mental health in general [37], but there is little research on mental health within Somali Bantu families.

Somali Bantu refugee resettlement in New England, where our study is based, is focused in urban, socio-economically disadvantaged communities. The Somali Bantu community that this study population is drawn from reports difficulties finding employment, housing insecurity, and overall financial instability [38]. They face many challenges due to language barriers [38]; it is not uncommon for households to be comprised of at least one parent who does not speak English, and children who do not speak Maay Maay, the Somali Bantu language. Although it is difficult for Somali Bantus in this community to access madrassas for religious education and other supports, there is a strong sense of community cohesiveness that is strengthened and supported by a Somali Bantu run self-help organization [38].

This research is part of a larger exploratory-sequential mixed methods study [38, 39] which has the aim of conducting a needs assessment of Somali Bantu refugee families in New England and designing and evaluating a family-based intervention for enhancing child and adolescent mental wellbeing. This study builds on earlier work [40] examining the impact of resource loss on Somali families, as well as preliminary work [38] with Somali Bantu families to further explore topics related to family relationships and mental health issues. In this study, focus groups were used to more specifically understand the relationship between resettlement, individual, family and community supports, and family functioning, building on this previous work and refining further the complex relationship between these systems among Somali Bantu families. The focus group design was chosen because they are recognized as a way of exploring participants’ ideas about community and family relationships more deeply than is possible with other qualitative methodologies [41].

In this present study, we used data from focus groups to address the following research questions:

How do different groups of Somali Bantu refugees describe their experiences of culturally adapting to life in the US?; and

How, if at all, do processes of cultural adaptation in a new country affect Somali Bantu family functioning?

Understanding how cultural adaptation relates to refugee family functioning can help identify what kind of psychosocial interventions might serve to reduce intergenerational conflicts and strengthen families, ultimately promoting better mental health outcomes for refugee youth.

Methods

Participants

Study participants were Somali Bantu refugees living in a large metropolitan area in New England interviewed between 2011 and 2013. Eligibility criteria for youth included being between the ages of 10 and 17 and a first-generation refugee born outside of the United States, either in Somalia or a refugee camp in Kenya. Adults were eligible to participate if they were a Somali Bantu parent or caregiver of a school-aged child or recommended by others in the community as a member of the Somali Bantu community who was knowledgeable about challenges facing Somali Bantu families. A total of 81 Somali Bantu refugees participated in 14 focus groups (see Table 1). The focus groups were divided into four groups of Somali Bantu refugees: male youth (4 groups); female youth (4 groups); male adults (3 groups); and female adults (3 groups). Researchers obtained ethical approval for this study from the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Table 1.

Study participants

| Age | Male (%) | Female (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10–14 | 6 (14.6) | 12 (30) | 18 (22.2) |

| 15–17 | 18 (43.9) | 11 (27.5) | 29 (35.8) |

| 18+ | 17 (41.5) | 17 (42.5) | 34 (42) |

| Total | 41 (50.6) | 40 (49.4) | 81 (100) |

Procedures

This study data was collected as part of a larger community-based participatory research study comprising a partnership between the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a community-based advocacy organization created and run by Somali Bantu refugees.

The study research manager, a community organizer within the Somali Bantu community, worked in conjunction with Somali Bantu research assistants (RAs) and other community leaders to ensure that they identified all Somali Bantu families residing in the area known to the community organizations, and assessed eligibility status of adults and youth. RAs approached eligible individuals for study participation, and used snowball-sampling methods to aid in recruiting Somali Bantu community members who represented a range of involvement to the refugee community association. Recruitment continued until there were sufficient participants for multiple focus groups in each of the four categories. Verbal informed consent was obtained from adults prior to the start of focus group interviews. Both verbal parental consent and child assent were obtained from all youth prior to participation. All study participants were compensated for their time with $20 in cash.

A semi-structured interview guide from a previous study [40] was modified for the purposes of this study. The version used in this study is contained in Appendix 1 in Electronic Supplementary Material. The interview guide was developed in English and then forward translated by RAs into Maay Maay— a Somali Bantu language. Two people, at least one of whom was Somali Bantu, facilitated focus groups. Interviews were conducted in Maay Maay or English, depending upon the preference of group participants. In groups conducted in Maay Maay, English-speaking study staff participated with the assistance of a live interpreter. A debriefing with the research team followed after the completion of each focus group. Based on these debriefings, the initial interview guide was refined over time to be responsive to the emergence of new topics and issues that came up spontaneously in the groups that were viewed as salient to the central aims of the study. All interviews were audio-recorded, de-identified, and transcribed into English by Somali Bantu RAs.

Data analysis

Data were managed and analyzed in MAXQDA 11 mixed methods software [42]. Researchers analyzed the data in several phases, based on principles of thematic analysis [43, 44]. The data analysis team included both those who had worked with the Somali Bantu community previously, and those for whom this was their first experience of working with this community, meaning the team encompassed a range of perspectives. In the first phase, two team members analyzed transcripts using a mixture of deductive and inductive coding as a strategy to identify patterns and topics emerging from the data that were pertinent to issues of resettlement stress and family functioning, informed by themes identified in a related piece of work [40], but open to new areas of focus driven by data in the transcripts. Based on research team discussions of individual transcripts, these initial codes were refined and grouped into larger categories of linked codes. For instance, codes including “religion,” and “dress and clothing” were grouped into a larger category labeled “differences between US and Somali Bantu culture.” The authors created a code-book that contained definitions and examples of both individual codes and larger categories.

In the next phase, three members of the team applied the same established coding scheme to 6 out of 14 transcripts. The coders met to discuss and resolve discrepancies in coding these six transcripts to reach consensus and ensure consistency between coders. If necessary, an outcome of these meetings was further refinement of the codebook by adding new codes, merging existing codes, and/or clarifying the definition of codes to maintain consistency throughout the coding process. The data analysis team then split up and individually coded the remaining seven transcripts. During this single coder phase, the team continued to meet to discuss any issues, concerns or challenges they encountered in the process, allowing for reflexivity and maintenance of consistent coding. Further codebook refinement was done as necessary. For instance, one coder identified a new topic of resettlement stress, “bullying in school,” after coding a Somali Bantu youth focus group.

Next, the three members of the data analysis team divided up the transcripts according to age and gender, to gain a richer understanding of how each group experienced and described the cultural adaptation process. Two analysts took the lead in reviewing transcripts and codes related to cultural adaptation among youth, with one focusing on male youth and the other on female youth; the third analyst focused on the transcripts from the adult focus groups. Analysis was informed by the acculturation-gap distress model [22]. Analysts identified overarching themes for each group, paying attention to differences, if any, based on age and/or gender. After conducting these separate analyses, team members met to review findings, identify patterns of similarities and differences both between and within focus groups, and agree upon overarching themes. Again, these discussions allowed for reflexivity among the analysis team.

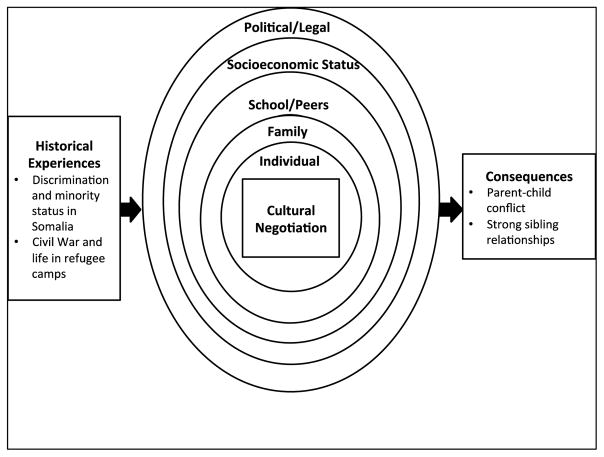

Finally, further comparisons of themes across the different groups (age, role and gender) were made. This analysis was informed by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory [10, 11], paying particular attention to the macrosystem and chronosystem in this stage of the analysis. Findings were considered in terms of the implications of cultural negotiation for family relationships among resettled Somali Bantu refugees. The analysts ensured that each theme was supported by qualitative data found in multiple focus groups. Quotations that best captured findings agreed upon by the research team were included for use in the present manuscript. A model of the negotiation process and family functioning that was informed by this analysis and Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework [10] can be found in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Model of Somali Bantu refugee resettlement, cultural negotiation, and family relationships in the context of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework

Results

Historical context

Two historical experiences were important precursors to cultural identity construction in the context of Somali Bantu refugee resettlement in the United States. These historical contexts (part of the chronosystem) [10, 11] consisted of discrimination and minority status in Somalia before the war, during the civil war and life in Kenyan refugee camps. The marginalization Somali Bantus faced in Somalia before the war was an important precursor to the struggles Somali Bantus in this study faced after resettlement and how they forged their identity in the United States. Their history of poverty and limited access to education and employment opportunities in Somalia is particularly salient to understanding barriers to success in the United States. One female adult described the connection between jobs available in Somalia and her current employment struggles:

“When I was back in Africa, we were doing other jobs different from what people were doing here. We would go to families that have money and clean their house, wash their clothes. I came to America and am ready to work, but you need some kind of experience. For citizenship, you need to know the language, so we need support from the government. When we came over here, we had zero knowledge. We didn’t know anything about what was going around. I didn’t even know how to write my name.”

Two adult male participants spoke about the disadvantages they faced because of their limited educational experiences in Somalia. When one participant stated, “it is difficult for us to study because none of our grandfathers or people where we came from did this kind of study,” a second followed up by adding, “As Somali Bantu, we have a lot of bigger problems. All of this is caused by education. I am not saying we are ignorant, but compared to the world we don’t know anything.”

A second important historical context was the civil war in Somalia and subsequent flight to Kenyan refugee camps. Adults described the traumatic experiences they survived, and how it currently affected them. An adult female stated,

“We did have very hard times back there in Somalia - a lot of our first bad memories. Sometimes you’re with your parents and there were warlords who would come and rape you in front of your parents. They kill you in front of your parents or your parents get killed in front of you. There’s nothing you can do to help. Back in Somalia, we did have many problems and challenges. Thank God we survived that. We had to walk from Somali to Kenya, for 13 days we walked. We did not just come here. All the problems that happened to us led us to come here. In the refugee camp, it was still a struggle. In the beginning, we were given tents. We struggled because we were in the tents and there were people who were Somalians before the war, come to kill and rape. We did not have a good shelter. We had many challenges, many problems, that will always stay in our heads, that we’ll never forget.”

For Somali Bantu youth who had limited, if any, memories of life in Somalia or Kenya, the loss or separation from family members during and after the war resulted in a fragmented sense of identity. An older male youth discussed his personal struggles,

“I never met my father because he died before I was born…don’t even remember coming to Kenya and stuff and coming to the United States. I don’t even have a memory of how mom and dad looked like. They say I have siblings. I’ve never met them, so it kind of affected the whole family because, well, I’m the only one affected in my family because I can’t seem to have a memory of anybody. Only my brother. Only him. And it’s kind of like, they say my father died before the war even happened, so it’s kind of hard to deal with. In school, I used to have a challenge of, like, people calling you a bastard because they think you don’t even know your father, you don’t even know your mom.”

Cultural negotiation

Somali Bantu adults and youth developed strategies and processes related to cultural negotiation in resettlement. A Somali Bantu male youth described what he wished the process could look like:

“Americans talk about their, like, back how they formed their community in America and how they established their own country, but we respect their point of view about how their culture was, but why don’t they help us with our culture and how we used to be in our past? So, our future generations will feel comfortable about where they came from and also respect American culture, and try to intertwine together and live in harmony, instead of all the kids talking about ‘your culture’ et cetera. Try to teach those American kids our culture too and not only that we have to learn their culture and keep it moving from there.”

Unfortunately, the historical context and contemporary circumstances in which Somali Bantu refugees were adapting to life in the United States led to a process of cultural negotiation that fell short of this ideal. Contextual factors within the macrosystem, including the larger US socio-political environment and legal frameworks, the school environment and peers (mesosystem), and family systems (microsystem) influenced the strategies they used [10]. The importance of these contextual factors varied based on the age of study participants. While Somali Bantu youth identity construction was influenced most heavily by interactions with peers, school and family environments, adults negotiated their cultural identity in response to contexts such as socioeconomic status as refugees and US legal frameworks.

Youth barriers to successful cultural negotiation: between peers and parents

Somali Bantu youth spoke a great deal about the impact the larger socio-political environment in the United States had on them, and facing discrimination because of their identities as Africans, Somalis, and Muslims. Somali Bantu youth were part of a racial minority in their schools, and heard racist comments from peers. Youth also spoke of being bullied and teased by peers who called them “Somali pirates.” One older female youth stated,

“I’ve heard people confuse Muslim and Bantu together, I mean, Somali and Bantu together. Because Osama Bin Laden, I don’t know if he’s Somali, but like, whenever someone says they are from Somalia, they think. They compare them, they are like terrorist, so I really… They call them a terrorist, because of him. So he just basically gave Muslim people and Somalis a bad name…He just killed people, so now people, now Americans like think Somalis, like Muslims, are terrorists.”

Youth described the difficulties of trying to function in an environment where their religion was equated with terrorism. An older male youth explained,

“They talk so much stuff about your religion, trying to make you feel bad about it, trying to show you, trying to, what’s it called, say to you that this religion is better than this religion. Like, most of the times when someone knows I’m a Muslim, like, say even a friend, when they’re joking around, it kind of hurts, but you have to put a smile on your face and just carry on. Like when they say, ‘look at the Muslim they did 9/11, they did this, they did that, look at Osama Bin Laden, look at Saddam Hussein, all of that.’ They talk so much stuff about your religion. It hurts, but you just gotta put the smile on your face and just keep moving because there’s nothing you can do about it because what happened, happened. It’s the past. But I know, where we come from, I haven’t heard anything about our country doing this or doing that; our religion doing this or doing that. That’s from a different country. Two countries cannot be the same. And they’re judging us from their own opinion, but they don’t see us as who we are.”

Somali Bantu youth in this study responded to this discrimination by trying to “hide” their Somali and Muslim identities when at school. For girls, this often came in the form of removing their hijab once they got to school and wearing more “American” clothes. One older male youth talked about the extent youth would go to distance themselves from their religious and cultural origins:

“Nowadays when you ask a kid, ‘where you from,’ they hide. They say, ‘I’m from Kenya.’ No you’re not. You were born in Kenya, but you’re from Somalia. People hide that because of the war that’s going on in Somalia. They don’t want to be a part of it, so they, when someone asks them where they are from, they say Kenya, but they’re not from Kenya. They were born in Kenya, but they’re originally from Somalia, but people don’t want that any more. They, when they say, when the schools are doing talent shows, they bring Kenyan flag, like, they say, ‘I’m from Kenya’… kids don’t choose Somalia because they know that if they say Somalia, someone is going to say something about it, so they choose Kenya because that’s where they were born. That’s what they turn to.”

This idea of “choosing” a different cultural affiliation to fit in at school was at odds with the pressure they felt within their families to maintain a traditional Somali Bantu identity. Somali Bantu parents in the focus groups discussed the expectations they had of children in terms of following parental rules as well as responsibilities youth had as a member of a larger family and Somali Bantu community, both in the short and long term. One father summarized, “What I expect from my children is to be peaceful, to be more educated, and to help each other. We expect them to be a leader. When they grow up I want them to help us as a community.” Parents wanted children to respect the authority of parents, assist in taking care of the household, and ultimately support other Somali Bantus.

Youth participants had conflicting feelings about the responsibilities they were expected to take on within the household. Both male and female Somali Bantu youth felt that their parents placed greater responsibilities on them with regards to things like childcare and financially contributing to the family than US-born parents did with their children. Female youth talked frequently about needing to help their mothers take care of younger siblings and do household chores. One female youth stated,

“Like in my family, my brothers and sisters are really like…they get sick a lot, and my mom needed me, I need to support them and everything. I didn’t really go to school as much, ‘cause I needed to be there, to go to the store, buy some medicines or get some sugar or whatever we need, so I had to be there for my mom and everybody else, ‘cause my dad was always busy and everything.”

Youth participants recognized that these were their parents’ responsibilities as youth growing up in Somalia, but became resentful when these tasks got in the way of them succeeding educationally, particularly given the intense pressure they felt around finishing high school and going on to college.

Parents were very hopeful that their children would be able to achieve things in America that they themselves were never able to in Somalia or Kenya. A parent explained, “We want the children to show us something that we never expected. We want them to get a higher education, a better job.” These expectations were clear to Somali Bantu youth in the groups, and they understood them within the context of their parents’ experiences in Somalia and during the war. One older female youth noted, “I think they suffered a lot, and that will never go away, and until they know that you are settle[d] down and you get everything that you needed, they are not going to let you go.”

Somali Bantu youth participants struggled when it came to meeting these high expectations, particularly when they had different desires and goals for themselves. One male youth stated,

“What they expect from me is that I could be successful in life, so that I could help support them in the future. Basically, my mom says she wants me to become a lawyer. My father says a doctor. But they’re not seeing what I want to be. I want to be an athlete plus a businessman. If I fail as an athlete, I get injured in a way, I can fall back and become a successful businessman, but that’s what I want them to support me in. They know that I want to be a businessman. I haven’t had the heart to tell them that I want to be an athlete also.”

Adult barriers to successful cultural negotiation: language acquisition and negotiating parenting

For Somali Bantu adults, decisions around negotiating traditional Somali Bantu culture and acquisition of new cultural practices were most often informed by their socioeconomic status as refugees and US legal frameworks. Adults talked about experiencing new challenges providing for their children in the United States and facing resettlement stressors related to finding and keeping good employment and affordable housing to support their families. Youth participants were aware of the struggles their parents faced resettling in the US, and described parents as depressed, angry, and worried. One male youth reflected, “It’s hard to find a job. You’re going to be worried, like, how are you going to take care of your parents? Take care of the children? Take care of your family – for the fathers I think. They have to worry about that. They need some help.” In this context, Somali Bantu adults spoke most about the importance of learning English for the purpose of finding employment, obtaining entitlements, and achieving citizenship. One adult male stated, “Adults also need to learn something because this country where we live now, if you don’t speak English it’s very hard for you to live. All people speak English.” Another male noted the link between language and financial survival,

“But other people are still struggling and need housing. We have seen their problems. The reason why they don’t have housing is, they don’t know where the office for the housing is and they don’t know how to fill out the application. For the person who knows where the office is, they can go to the office and get an education. The other problem is if you don’t know how to communicate with the people in the office, how are you going to do that.”

Yet another remarked, “The reason why I failed my citizenship right now is because I am scared. Why I am scared is because I know how to write, but the writing I know is not English. I don’t know English, and they want you to read. I don’t know how to do that.”

In addition to language acquisition, Somali Bantu adults discussed needing to adjust to new norms around parenting practices in the United States. Parenting was difficult because Somali Bantu parents could no longer use disciplinary practices that had been common in Somalia. One female parent stated, “We used to discipline them with a small stick, and if you discipline them today, tomorrow they won’t be disrespectful. But now, they do whatever they want. As a parent, there is nothing you can say.” Adults saw a connection between being unable to use harsh punishment, subsequent loss of authority as a parent, and the emerging struggle to maneuver parenthood within what they saw as a new, US-enforced family power dynamic. A male participant summed up this new dynamic by saying, “When we come to America, what they say were that the parent and the child were the same.” Older youth who more clearly remembered life in Somalia reflected on the changes in disciplinary practices, and saw connections between parental discipline (or lack thereof) and youth behavioral problems. One female youth noted, “It was better back in our country, because now, the parents don’t know how to discipline the kids, they don’t hit the kids and everything, so now, the kids are out of control.” Within the same focus group another youth added, “they [parents] are afraid to go after their own kid it’s because they can’t do whatever they want to because once they come here, it’s not their own kids, they feel like the government owns their kids too, I guess.”

Parents also discussed having to negotiate new responsibilities around keeping children safe. In this regard, adults talked about a way of parenting in Somalia that went beyond the scope of biological parents, and included neighbors and extended family; shifting to new norms in America was exceedingly difficult. A female parent explained:

“When we were in Africa, we were not afraid about our children walking around. If the child is at your house, I don’t have to worry. All children around the neighborhood were playing together and we were all watching. If you are going to somewhere, you don’t have to worry about leaving them, the neighbors can watch it. Your child can go to somewhere in the city, they just play. When they get hungry, they come back. You don’t have to worry like here.”

Once in the US, many families were resettled in urban housing projects that brought their own dangers. Parents were both genuinely more concerned for the safety of their children and also frightened as to the consequences if something happened to their child and police got involved, especially of having children taken away from them. One adult summed up the contrast between keeping children safe in Somalia or Kenya compared to the US by simply stating, “The way they used to raise their children in Africa, children were free, but in here they’re not free.”

Cultural loss and maintaining a Somali Bantu identity

Outside of learning English and not being able to use the same disciplinary practices, Somali Bantu adults were committed to maintaining a traditional Somali Bantu identity for themselves and their children. Adult participants reflected on the differences between life in Somalia, Kenya and the United States, as their culture became something less embedded in daily experiences and instead became something that needed to be more explicitly taught and instilled in youth. One adult lamented,

“We don’t have a culture here, we left our culture back in Kenya. When we come over here, every city a few blocks you see a lot of churches. We live in between different religions, communities. The reason why I say we left our culture back home is when we used to live in Africa, we used to dance, we used to sing songs every week. We used to come together.”

The role of a Somali Bantu parent, according to adult focus group participants, was to make sure their child became a successful Somali Bantu adult, one who was married with a family of their own. The means to achieving this were a combination of religious education, strict discipline, and instilling familial and communal responsibilities of youth early in life. Access to madrassas [religious education] was viewed as particularly important in terms of instilling respect for parents and others in the community. An adult female explained about life in Africa compared to the US, where madrassas weren’t readily accessible,

“What the parent were doing is when the child start speaking, they take the child to a madrassa to teach the child about the religion. If that child learns the teaching of the religion very well, that child is going to be a good, well-behaved child. When the child is raised in there, that child learn about their parents and the older people and they respect their older brother, sister, and their parents. But when they are born in here [the US], they don’t respect their brothers and sisters. They don’t respect the older people. They don’t respect their parents.”

Ultimately what emerged in focus group discussions was a picture of Somali Bantu adults who were committed to being good parents and carrying out the responsibilities of parenthood, but unclear on how to fulfill these responsibilities in a new environment. In trying to negotiate an identity as a Somali Bantu parent, participants were at a loss as to how to “do” parenting in the US. A woman reflected, “Every country that you go to, in a new place, it’s hard to adapt to everything. For us here, there’s still one thing that’s hard to adapt to and that’s how to raise kids here.”

Parent–child misappraisal

The strategies of cultural negotiation of Somali Bantu adults and youth had two primary consequences. These included an increase in parent–child conflict, and also the strengthening of sibling relationships. The vast majority of adults included in focus groups felt that children were not interested in maintaining traditional cultural practices, something parents interpreted as disrespect. One female adult described her interactions with her children, “When the child grow up [in Somalia], around age 10, they start praying. They go to madrassa. They come back home. But here, the only thing they know is go to the school, come home, and watch Barney. When you asked the child to wear the traditional clothes, they throw at you.” A second parent acknowledged some differences based on the age of children:

“The older children, they understand sometime to wear the clothes that you asked them to wear. They cover their body. But the difficult thing for them is to pray. If you asked them, come read the Quran or do something about the religion, they just don’t want it. If you talk to them our own language all the time, they just don’t understand it. And that’s a hard thing between the parent and the child. All we are expecting or all that we want is our child to follow our way. We want them to follow our culture.”

Based on data from adult focus groups, parent–child relationships were rife with conflict because of the lack of agreement over the importance of maintaining a Somali Bantu cultural identity.

A very different picture was presented by youth from the focus groups. Both older and younger Somali Bantu children talked about the importance of holding on to Somali Bantu culture, and the struggles they faced trying to balance fitting in both at home and the larger American society. Somali Bantu children in the groups were well aware that parents perceived them as being disobedient and disrespectful if they did not strive to meet the expectations that had been set for them, both in the present and longer-term. Youth felt guilty about this, and pressure became even greater when children viewed their behavior as key to their parents’ happiness given the context of their experience as refugees. A female youth explained,

“You just think you can do whatever you want. But your mom worked so hard to bring you to a safe place, so…you don’t have to go through the problems that she did. And so, your life will be a little bit easier than hers. But if you don’t like, if you don’t disrespect her, maybe she’s not even going to remember that. But if you do disrespect her and you always make her cry and stuff like that and then if you remind her of that, then it wouldn’t be good for her.”

They described a challenging process by which they felt “consumed” by American culture, all the while knowing they were disappointing their parents. Speaking more specifically about adhering to religious practices, one male youth explained,

“Basically, people like, I think some people they really try hard to keep their faith, but sometimes they get overwhelmed by society, so people and every corner where you go, everywhere you go some people might not know your religion, don’t know your religion, and they ask you: ‘why you dressed like this? Why are you like that? Why don’t you act like an American?’ The fact is that I was not, I’m not an American. I’m from Africa. I was raised in a family, and I know how to respect my elders. I’m not saying that American kids can’t respect their elders, just that they try to get you so mad and try to get under your skin that sometimes you just don’t know what to do any-more.”

What youth participants expressed was the desire for their parents to understand their experience and acknowledge that being in a new environment meant that children felt they needed to negotiate their identity based on the context to succeed. A female youth expressed,

“I think like my mom is worried about us…She was like ‘I think you are forgetting who you are’ or something, but we are not. She just go… I don’t know, she just overthinking herself, because we would never forget who we are. Like, we know who we are, we are just, we are just in a new place. And I don’t think they understand that we are not always at home, we go to school, and sometimes it’s hard to fit in. And sometimes a lot of Somali kids do a lot of things that people at school do ‘cause they want to fit in… So…yeah…I don’t think my mom understands that we are kids, and that, you know, this is not like the old days.”

Sibling support and “co-negotiation”

The process of cultural negotiation did not mean that Somali Bantu family dynamics were solely overtaken by conflict; instead, there was a mixture of increasing tension in parent–child dyads, and greater support and solidarity among siblings. On a practical level, many children under 15 had forgotten much of their Maay Maay, and relied on older siblings to translate between them and their parents at times. Younger children also talked about turning to older siblings, as opposed to parents, for emotional support, because older youth were able to identify with and understand their experiences. One female youth described this relationship,

“All the sibs get along with each other ‘cause we could tell each other stuff that we could not tell our parents, it’s like it’s hard. It’s [easier] to explain to them than the parents, it’s not hard because they are willing to listen to you. They [parents] won’t be listening […] it’s giving us a hard time to tell them, but tell a sibling, it’s easier. They understand you, they know what you are going through, they are going through the same thing.”

As noted earlier, one of the shared experiences of many youth, regardless of age, was facing discrimination and bullying at school because they were Muslims from Somalia. This led to fights at school, with Somali Bantu youth getting into trouble. Children were afraid to tell their parents, or felt that their parents would not be able to help because of language barriers. Instead, youth went to siblings for help. Older Somali Bantu male youth felt particularly protective towards their sisters:

“Yeah. Anything that they need help that I could do, they come to me. Like, sometimes my little sister she fight in the bus when other kids they tried to pull off her hijab, and she smacked them. The bus driver tried to suspend her from the bus, but wouldn’t suspend the kid that was doing the wrong in the first place. I told my parents, but the school teacher said that I cannot do anything about it, that’s the bus. And I said: ‘you’re the teacher, both of the kids are in the same class what do you mean you can’t do anything about it?’”

These sibling relationships, then, helped to compensate for some of the rifts in parent–child relationships, with youth feeling a heightened level of responsibility for their siblings that went beyond providing childcare and parenting support expected by their parents.

Discussion

This study explored the process of negotiating cultural identity and its effect on family functioning among Somali Bantu refugee adults and youth resettled in New England. A theoretical model was developed based on an examination of the experiences of 81 Somali Bantu refugees through qualitative data analysis. This model proposes a dynamic process in which family relationships are simultaneously strengthened and strained, and cultural negotiation is dependent upon broader sociocultural contexts and environments in the United States that are most salient to the experience of the individual.

We identified a range of themes indicating how parental responsibilities and the expectations of youth shaped parent–child interactions. Both adult and youth participants reported similar views on the parental responsibilities of Somali Bantu parents and what constituted good parenting, including taking care of basic needs and keeping children safe. These findings align with previous research on Somali majority and Somali Bantu parents. Unlike in Somalia, where children could move around freely, many parents voiced concern over their children’s safety and felt children required close monitoring and supervision [45, 46]. Parents also expressed concerns over changes in parenting power, lack of disciplinary authority, and children not respecting parents [38, 45, 47, 48]. Many of these challenges were attributed to the influence of Western culture on children [38, 48].

In contrast, Somali Bantu adult and youth participants had conflicting views, notably around expectations of youth and negotiating Somali Bantu culture, which often times led to strained parent–child relationships. While both expressed high hopes and expectations, Somali Bantu youth and adults tended to define these expectations differently. We found that Somali Bantu children perceived having greater familial responsibilities than their peers. This aligns with other research in which older youth found the burden of familial responsibilities often interfered with opportunities for educational advancement, and in some cases even completing high school [49]. However, Somali Bantu youth also commented on their close sibling relationships, where siblings offered support not only to cope with stressful parent–child relationships, but also to act as translators, supports, and confidants.

Although both Somali Bantu parents and youth spoke about the importance of maintaining Somali Bantu culture, parents often did not recognize the struggles youth faced in negotiating Somali Bantu culture in the US. Children reported experiencing cultural discrimination at school and being bullied because of their Somali Bantu identity leading to fights at school and on the bus, yet most youth saw their Somali Bantu culture as an integral part of their identity. However, Somali Bantu parents were often unaware of the stressors children faced at school, either because of language difficulties or children intentionally not telling their parents about issues around discrimination. Reports of cultural discrimination and harassment have been identified in several other studies with Somali and Somali Bantu youth [33, 40, 49, 50].

This study addressed family functioning from both the adult and youth perspective, which allowed for a better understanding of the parent–child relationship. While several studies have examined the parent perspective on family relationships and the process of cultural adaptation [45, 47, 48], our study highlights the importance of also including the perspective of young people, as family dynamics are complicated and more nuanced. Important differences emerged in the views of adults and youth. Differences in interpretation of the same situation between adults and youth demonstrate the importance of including both perspectives. For example, conflicting expectations of youth, and conflicts over maintaining Somali Bantu culture would have been lost had we not interviewed youth.

Theoretical implications

These results contribute to our understanding of the acculturation-gap distress model in several ways. Criticism of the model includes its neglect of the wider context in which parent–child dyads sit [51]. To use Bronfenbrenner’s terminology, in the context of the Somali Bantu participants in these focus groups, this wider context includes other members of the family microsystem, such as siblings; the youth’s mesosystem, including the children’s school; aspects of the exosystem, such as the help given to refugee families by government assistance projects, and the broader macrosystem in which all residents in the United States operate, such as wider political climate [10, 11]. The work included in this study demonstrates the complexities of cultural negotiation: it is not a process that occurs in response to a single level of a host culture, but to multiple levels (or systems), which in turn interrelate. As an example, wider political and social discourse that promotes negative attitudes towards Muslims in the macrosystem can lead to bullying and discrimination towards Somali Bantu youth in the mesosytem, which in turn can cause tensions between parents and children over clothing in the microsystem. It is impossible to separate out these processes, and future work is needed to understand how youth who are able to more successfully negotiate their cultural identity interact with different systems within their host culture, and the relative importance of these systems for positive and negative outcomes among refugee youth and their families.

Another criticism of acculturation-gap distress model research is the isolated focus on parent–child dyads [51]. This current study moves beyond such a narrow scope and considers the impact of sibling relationships in the cultural negotiation process. The data described previously highlights some of the potentially positive impacts of sibling relationships for refugee youth who are navigating the process of cultural adaptation. Finally, much literature on the acculturation-gap distress model treats the gap as something that is static [22]. This study clearly highlights how this relationship between cultures is dynamic for both parents and youth. It demonstrates that parents and children must negotiate the process throughout all stages in their lives, as youth mature from children into teenagers and then young adults. This is not a process that is ever “complete”; rather, it is something that requires constant consideration. Both parents and children are exhibiting different manifestations of negotiation at different points in their lives, depending on what they choose to prioritize. For example, youth may reject or resent the childcare responsibilities placed on them as older teenagers, yet happily choose to marry according to their parents’ expectations as a young adult.

Clinical implications

Therapeutic interventions for refugees are largely characterized as being trauma-focused and geared towards working with individuals [52–54]. To date, there are few evidence based family-level interventions for refugees that address the stressors families face after third country resettlement [55]. This is a major shortcoming given the role family functioning among refugees can play in both promoting resilience and contributing to adverse outcomes of youth [56, 57]. And while addressing the mental health impact of exposure to discrete traumatic events experienced by refugees is extremely important, there is also a need to provide services that have a broader focus [58]. Addressing the mental health needs of refugee youth will require practitioners to have awareness of family-level dynamics and the impact of interactions with other systems on the wellbeing of children and adolescents.

The present study highlights the experience of intergenerational gaps related to cultural identity that often emerges among refugee families and the stress it can add to parent–child relationships. By giving voice to both youth and parent perceptions and experiences of cultural negotiation, this study indicates that an important aspect of therapeutic work with refugee families includes promoting better communication between family members. Better communication may include identifying and facilitating conversations regarding misappraisals of this intergenerational gap. Parents perceived youth as more rapidly identifying with their host culture than themselves; in reality, youth voiced a great deal of ambivalence about embracing their host culture and experienced distress related to balancing Somali Bantu and American cultural norms. Facilitating family discussions around experiences of cultural negotiation can serve to correct these misappraisals and promote more positive parent–child relationships [59].

Although study findings identified parent-youth misappraisals as it relates to cultural negotiation, there were not only real differences in the two groups in the pace of adopting host cultural norms, but also a lack of awareness of reasons behind this gap. In this study, for instance, parents had limited knowledge of the discrimination children faced from peers because they were Muslim and from Somalia. This discrimination, in turn, served as a catalyst for youth to shed cultural practices of their country of origin. Providing psychoeducation to refugee families on the cultural adaptation process can serve to normalize the conflicts families experience and provide guidance on strategies to overcome challenges [60].

This study also has implications for clinicians working with refugee children or adolescents. Age of resettlement had different implications for youth in terms of the stressors they experienced and the role they played in family interactions and dynamics. Older adolescents often found themselves in the role of bridging the cultural divide between younger siblings and adults, in addition to trying to navigate their own blended Somali Bantu/American culture identity. Additionally, we found that youth looked to each other and siblings for both concrete and emotional support. Clinicians could build on this intra-generational support system and provide group-level services to refugee youth. Support groups for youth of different ages could provide a platform for youth to share the stressors they experience, particularly around parental expectations, and identify ways to communicate with parents and negotiate family relationships.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to our study. Firstly, due to the use of snowball-sampling, the participants may not be representative of all Somali Bantus living in large New England cities. This is because a number of participants were recruited through their connections to other participants in the study, so there may be a bias towards similar social groups within the Somali Bantu community. However, the team did purposely select for participants from both genders and across a range of ages to help ensure a range of perspectives. Furthermore, many of our findings related specifically to the interactions between Somali Bantu and American cultures, so they may not be generalizable to the experiences of Somali Bantu families living in communities outside of the US.

Secondly, due to the small size of the Somali Bantu community in the metropolitan area of our study, it is possible that focus group participants were known to each other. This could mean that they felt social pressure to conform to what others in their group were saying, and so gave more restricted answers than they might have done in a one-on-one interview. Finally, as previously discussed, there were members of the research team who were members of or who had previously worked with the Somali Bantu community. It is possible that members’ previous experiences of working with or being a member of this community affected their interpretation of the data. However, the use of regular team discussions at all points in the data gathering and analysis process means that individuals were given the opportunity to reflect on their analyses of the data, which helped to mitigate this source of potential bias.

Conclusion

We are in the midst of a humanitarian crisis due to war and political conflict that has not been seen since World War II [1]. Whether recently displaced from their home, in transit or temporary locations such as refugee camps, or adjusting to third country resettlement, refugee families are in need of psychosocial services and supports to prevent negative mental health outcomes in both the short and long term [8]. The wellbeing of refugee youth is influenced by larger societal, peer and family dynamics. Applying an ecological approach [10, 11] to address stressors related to cultural negotiation in new environments can serve to promote positive family functioning and refugee youth mental health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the entire Somali Bantu community, and more specifically the tireless efforts and dedication of Abdi Abdirahman and Zahara Haji. Thanks also to Rita Falzarano for her continued support and dedication to this project. Authors Frounfelker, Hussein and Betancourt were supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Grant #5R24MD008057-03. The National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Grant #3R24MD008057-03S1, supported author Assefa in full. For part of the time period of her involvement with this work, author Smith was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration Maternal and Child Health Training Grant # T76MC00001 for a separate piece of work. She is an NIHR Academic Clinical Fellow in Public Health, funded by the UK National Institute of Health Research. The views in this work are those of the authors and do not represent those of NIHR.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00787-017-0991-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval The authors obtained approval from the Harvard T.H. Chan Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Global trends: forced displacement in 2015. 2016 http://www.unhcr.org/576408cd7.pdf.

- 2.Hebebrand J, Anagnostopoulos D, Eliez S, Linse H, Pejovic-Milovancevic M, Klasen H. A first assessment of the needs of young refugees arriving in Europe: what mental health professionals need to know. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry. 2016;25:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0807-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Department of State. Proposed refugee admission for fiscal year 2017: report to congress submitted on behalf of the President of the United States. United States Department of State, United States Department of Homeland Security, United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anagnostopoulos D, Heberbrand J, Eliez S, Doyle M, Klasen H, Crommen S, Cuhadaroğlu F, et al. European Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: position statement on mental health of child and adolescent refugees. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry. 2016;25:673–676. doi: 10.1007/s00787-016-0882-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mossaad N. Refugees and asylees: 2014. Office of Immigration Statistics, Department of Homeland Security; 2016. www.dhs.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fazel M, Stein A. The mental health of refugee children. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:366–370. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.5.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronstein I, Montgomery P. Psychological distress in refugee children: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychiatry. 2011;14:44–56. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ventevogel P, Schinina G, Strang A, Gagliato M, Hansen LJ. Mental health and psychosocial support for refugees, asylum seekers and migrants on the move in Europe: a multi-agency guidance note. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki SE, Charrow AP, Tol WA. Interventions for children affected by war: an ecological perspective on psychosocial support and mental health care. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2013;21:70–91. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0b013e318283bf8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1977;32:513–531. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological models of human development. In: Postlethwaite TN, Husen T, editors. International encyclopedia of education. 2. Vol. 3. Elsevier; Oxford: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. Am Psychol. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry JW. Acculturation: living successfully in two cultures. Int J Intercult Relat. 2005;29:697–712. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatia S, Ram A. Rethinking ‘acculturation’ in relation to diasporic cultures and postcolonial identities. Hum Dev. 2001;44:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simich L, Maiter S, Ochocka J. From social liminality to cultural negotiation: transformative processes in immigrant mental wellbeing. Anthropol Med. 2009;16:253–266. doi: 10.1080/13648470903249296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SS. The experiences of young Korean immigrants: a grounded theory of negotiating social, cultural, and generational boundaries. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2004;25:517–537. doi: 10.1080/01612840490443464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stritikus T, Nguyen D. Strategic transformation: cultural and gender identity negotiation in first-generation Vietnamese youth. Am Educ Res J. 2007;44:853–895. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tardif-Williams CY, Fisher L. Clarifying the link between acculturation experiences and parent–child relationships among families in cultural transition: the promise of contemporary critiques of acculturation psychology. Int J Intercult Relat. 2009;33:150–161. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lincoln AK, Lazarevic V, White MT, Ellis H. The impact of acculturation style and acculturative hassles on the mental health of Somali adolescent refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;18:771–778. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0232-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Revollo HW, Qureshi A, Collazos F, Valero S, Casas M. Acculturative stress as a risk factor of depression and anxiety in the Latin American immigrant population. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2011;23:84–92. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.545988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suarez-Morales L, Lopez B. The impact of acculturative stress and daily hassles on pre-adolescent psychological adjustment: examining anxiety symptoms. J Prim Prev. 2009;30:335–349. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0175-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Telzer EH. Expanding the acculturation gap-distress model: an integrative review of research. Hum Dev. 2011;53:313–340. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Wagner KD, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Parent–child acculturation patterns and substance use among Hispanic adolescents: a longitudinal analysis. J Prim Prev. 2009;30:293–313. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0178-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ying YW, Han M. The longitudinal effect of intergenerational gap in acculturation on conflict and mental health in Southeast Asian American adolescents. Am J Orthopsychiat. 2007;77:61–66. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SY, Chen Q, Wang Y, Shen Y, Orozco-Lapray D. Longitudinal linkages among parent–child acculturation discrepancy, parenting, parent–child sense of alienation, and adolescent adjustment in Chinese immigrant families. Dev Psychol. 2013;49:900–912. doi: 10.1037/a0029169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menkhaus K. Bantu ethnic identities in Somalia. Ann Ethiop. 2003;19:323–339. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lehman DV, Eno O. Culture profile. Center for Applied Linguistics; Washington, DC: 2003. The Somali Bantu: their history and culture. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Besteman C. Making refuge: Somali Bantu refugees and Lewiston. Duke University Press; Maine: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chanoff S. After three years: Somali Bantus prepare to come to America. Refug Rep. 2002;23:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Besteman C. Translating race across time and space: the creation of Somali Bantu ethnicity. Identities. 2012;19:285–302. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Springer PJ, Black M, Martz K, Deckys CM, Soelberg T. Somali Bantu refugees in southwest Idaho: assessment using participatory research. Adv Nurs Sci. 2010;33:170–181. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181dbc60f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith YJ. ProQuest LLC PhD dissertation. The University of Utah; 2010. They bring their memories with them: Somali Bantu resettlement in a globalized world. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenhauer ER, Mosher EC, Lamson KS, Wolf HA, Schwartz DG. Health education for Somali Bantu refugees via home visits. Health Info Libr J. 2012;29:152–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2012.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deckys C, Springer P. The elderly Somali Bantu refugees’ adjustment to American Healthcare. Online J Cult Compet Nurs Healthc. 2013 http://works.bepress.com/pam_springer/18/

- 35.Roxas KC. Who dares to dream the american dream? The success of Somali Bantu male students at an American High School. Multicult Educ. 2008;16:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grady S. Improvised adolescence: Somali Bantu Teenage refugees in America. University of Wisconsin Press; Madison: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baker RE. ProQuest. 2007. A phenomenological study of the resettlement experiences and mental health needs of Somali Bantu refugee women. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Betancourt TS, Frounfelker RL, Mishra T, Hussein A, Falzarano R. Addressing health disparities in the mental health of refugee children and adolescents through community-based participatory research: a study in 2 communities. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:S475–S482. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Creswell JW. A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Betancourt TS, Abdi S, Ito BS, Lilienthal GM, Agalab N, Ellis H. We left one war and came to another: resource loss, acculturative stress, and caregiver–child relationships in Somali refugee families. Cult Divers Ethn Min. 2015;21:114–125. doi: 10.1037/a0037538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ British medical journal. 1995;311:299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MAXQDA, software for qualitative data analysis, 1989–2016, VERBI software—consult. Sozialforschung GmbH; Berlin: [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nilsson JE, Barazanji DM, Heintzelman A, Siddiqi M, Shilla Y. Somali women’s reflections on the adjustment of their children in the United States. J Multicult Couns Dev. 2012;40:240–252. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Renzaho AMN, Green J, Mellor D, Swinburn B. Parenting, family functioning and lifestyle in a new culture: the case of African migrants in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Child Fam Soc Work. 2011;16:228–240. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osman F, Klingberg-Alvin M, Flacking R, Schon UK. Parenthood in transition—Somali-born parents’ experiences of and needs for parenting support programmes. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2016;16:7. doi: 10.1186/s12914-016-0082-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Degni F, Potinen S, Molsa M. Somali parents’ experiences of bringing up children in Finland: exploring social-cultural change within migrant households. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2006;7:3. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donahue R. Realizing translations: exploring social environments of somali bantu refugee children in the United States. Graduate School of Development Studies at the Institute of Social Studies; The Netherlands: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ellis BH, MacDonald HZ, Klunk-Gillis J, Lincoln A, Strunin L, Cabral HJ. Discrimination and mental health among Somali refugee adolescents: the role of acculturation and gender. Am J Orthopsychiat. 2010;80:564–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Costigan CL. Embracing complexity in the study of acculturation gaps: directions for future research. Hum Dev. 2011;53:341–349. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slobodin O, de Jong JTVM. Mental health interventions for traumatized asylum seekers and refugees: what do we know about their efficacy? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61:17–26. doi: 10.1177/0020764014535752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murray KE, Davidson GR, Schweitzer RD. Review of refugee mental health interventions following resettlement: best practices and recommendations. Am J Orthopsychiat. 2010;80:576–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lambert JE, Alhassoon OM. Trauma-focused therapy for refugees: meta-analytic findings. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62:28–37. doi: 10.1037/cou0000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weine SM. Developing preventive mental health interventions for refugee families in resettlement. Fam Process. 2011;50:410–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2011.01366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sleijpen M, Boeije HR, Kleber RJ, Mooren T. Between power and powerlessness: a meta-ethnography of sources of resilience in young refugees. Ethnic Health. 2016;21:158–180. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2015.1044946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jung MJ. Dissertation. University of Tennessee; 2013. The role of an intergenerational acculturation gap in the adjustment of immigrant youth: a meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller KE, Rasmussen A. War experiences, daily stressors and mental health five years on: elaborations and future directions. Intervention. 2014;12:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Merali N. Perceived versus actual parent-adolescent assimilation disparity among Hispanic refugee families. Int J Adv Couns. 2002;24:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Merali N. Family experiences of Central American refugees who overestimate intergenerational gaps. Can J Couns. 2004;38:91–103. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.