Abstract

Objectives

To collect data of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and clinical controlled trials (CCTs) for evaluating the effects of enhanced recovery after surgery on postoperative recovery of patients who received total hip arthroplasty (THA) or total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Methods

Relevant, published studies were identified using the following key words: arthroplasty, joint replacement, enhanced recovery after surgery, fast track surgery, multi-mode analgesia, diet management, or steroid hormones. The following databases were used to identify the literature consisting of RCTs or CCTs with a date of search of 31 December 2016: PubMed, Cochrane, Web of knowledge, Ovid SpringerLink and EMBASE. All relevant data were collected from studies meeting the inclusion criteria. The outcome variables were postoperative length of stay (LOS), 30-day readmission rate, and total incidence of complications. RevMan5.2. software was adopted for the meta-analysis.

Results

A total of 10 published studies (9936 cases) met the inclusion criteria. The cumulative data included 4205 cases receiving enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS), and 5731 cases receiving traditional recovery after surgery (non-ERAS). The meta-analysis showed that LOS was significantly lower in the ERAS group than in the control group (non-ERAS group) (p<0.01), and there were fewer incidences of complications in the ERAS group than in the control group (p=0.03). However, no significant difference was found in the 30-day readmission rate (p=0.18).

Conclusions

ERAS significantly reduces LOS and incidence of complications in patients who have had THA or TKA. However, ERAS does not appear to significantly impact 30-day readmission rates.

Keywords: total hip arthroplasty, total knee arthroplasty, enhanced recovery after surgery, systematic review, meta-analysis

Introduction

The concept of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) was advocated by Danish surgeon H. Kehlet in the 1990s.1 Kehlet’s recovery model promoted a series of measures to optimise perioperative treatment. Kehlet used evidence-based medical interventions to reduce postoperative physical and psychological trauma and stress, and thus accelerate the recovery process. The core principle is to reduce trauma and stress by using the least invasive surgical practices, thereby reducing postoperative complications, saving costs, shortening length of stay (LOS), improving patient satisfaction, and promoting faster recovery. Its earliest use in gastrointestinal surgery achieved satisfactory results. In recent years, improvements in orthopaedic surgical techniques as well as those in anaesthesia technology have produced exciting clinical results in enhancing postoperative recovery, especially in joint surgery cases.

Despite these advances, the effectiveness of ERAS on arthroplasty has not been uniformly recognised or accepted by orthopaedic surgeons. Studies such as this meta-analysis are needed to inform a dialogue among surgeons to evaluate the use of ERAS.

Methods

Document retrieval

Authors Zhu and Qian reviewed and evaluated the relevant literature. They limited their search to investigations published prior to 30 December 2016 and to those listed in reputable, recognised databases including PubMed, EMBASE, Ovid and others. The keywords they used for the search were: arthroplasty, joint replacement, enhanced recovery after surgery, fast track surgery, multi-mode analgesia, diet management, and steroid hormones. The search protocol also specified that each study used either a randomised control trial (RCT) or a clinical controlled trial (CCT) approach specifically focused on ERAS after total hip arthroplasty (THA) or total knee arthroplasty (TKA). All studies included were published in English.

Inclusion criteria

These included patients in the ERAS group who received treatment measures of enhanced recovery after arthroplasty, while those in the control group were subjected to traditional recovery therapy. All studies cited could provide relevant data. (Thus, the meta-analysis was restricted to a review of only those published investigations that clearly provided sufficient evidence of the techniques used in perioperative recovery. All investigations cited meet this criterion.)

Exclusion criteria

These included literature reviews, case reports and studies with only a single cohort or other studies not employing a control group; studies without relevant postoperative indicators; enhanced recovery after surgery for other types of arthroplasty (ie, sites other than hip or knee); and repeats or re-workings of previously published literature.

Data extraction

The two investigators reviewed the abstracts and titles, carefully read the full texts according to preset inclusion criteria, and extracted the relevant clinical information, research information and other information, including the authors, years of publication, sample sizes, age and sex of subjects, and specific recovery measures, surgical sites, postoperative complications, LOS and readmission rate of patients after 30 days in the ERAS group and the non-ERAS group. The data were arranged into experimental form and Excel spreadsheets in duplicate. All data extraction work was done by two authors independently. When any inconsistency arose, the issues were either resolved by a third investigator or negotiated by both the original investigators.

Qualitative evaluation of cited studies

The relevance of each investigation was assessed according to the number of criteria it met. The following five evaluation indicators were used to assess the quality of the included investigations: (1) randomisation; (2) allocation concealment; (3) blind intervention and outcome assessment; (4) interruption or discontinuation of postoperative treatment; and (5) intentional analysis. A study received an A rating if all five criteria were met; a B for three to four; and a C for two or fewer.

Definition of outcome events

The main outcome events were postoperative LOS, 30-day readmission rate, and total incidence of complications. LOS was defined as time from hospital arrival on day of surgery to discharge from the hospital (unit: days). The secondary events were visual analogue scale (VAS) score, patient satisfaction, hospital costs, and other reported outcomes.

Statistical methods

For each included study, mean differences (MDs) and 95% CI were calculated for continuous outcomes, while odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI were calculated for dichotomous outcomes. Statistical heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using the χ2 test and I2. A fixed effect model was applied when I2 <50%, and a random effect model when I2 >50%. Otherwise, a random-effects model was adopted and subgroup analyses or a sensitivity analysis would be carried out. All analyses were completed with Review Manager 5.22 3 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and a p-value funnel plot was used to analyse the existence of publication bias.4

Results

Basic characteristics of included studies

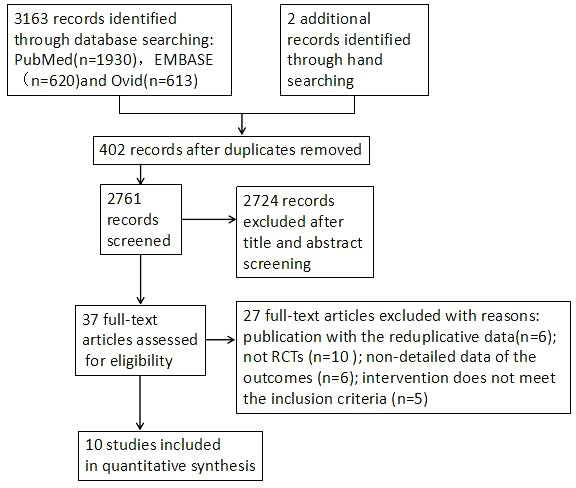

The flow of study identification and inclusion are shown in figure 1. In summary, over 3000 individual papers were initially identified. Based on our review of the title and abstract, 37 full-text papers were reviewed and 10 met the study inclusion criteria. The 10 studies involved 4205 participants who received ERAS and 5731 who received a control intervention. All 10 papers had complete reporting of LOS, seven had data on the incidence of any postoperative complication, and five papers reported 30-day readmission. The papers had similar distributions of sex, age and types of surgery. The included studies are described in table 1. LOS data are summarised in table 2 and postoperative complications in table 3. The 30-day readmission data are given in table 4.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of searches.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics and quality assessment of included literatures

| Studies | Year of publication | Country | ERAS | Non-ERAS | Study quality |

| N, male/female, age (years) mean (SD) | N, male/female, age (years) mean(SD) | ||||

| Auyong DB5 | 2015 | United States | 126, 41\85, 68.44 (9.98) | 126, 44\82, 66.02 (10.02) | B |

| Christelis N6 | 2015 | Australia | 297, 113\184, 67 (10) | 412, 164\248, 68 (11) | B |

| denHertog A7 | 2012 | Germany | 74, 23\51, 66.58 (8.21) | 73, 20\53, 68.25 (7.91) | B |

| MaempelJF8 | 2015 | England | 84, 42\42, 69.8 (8.9) | 81, 40\44, 70.1 (10.5) | B |

| Malviya A9 | 2011 | England | 1500, 711\789, 68 | 3000, 1482\1518, 69 | B |

| McDonald DA10 | 2012 | England | 1081, 439\642, 69 (11) | 735, 307\428, 70 (13) | B |

| Scott NB11 | 2013 | England | 405, __, 68 (11) | 873, __, 68 (10) | B |

| Stambough JB[12 | 2015 | United States | 488, 247\241, 55 (19) | 281, 126\155, 59 (16) | B |

| Stowers MD13 | 2016 | New Zealand | 100, 47\53, 66.7 (9.2) | 100, 41\59, 65.4 (12.5) | B |

| Talboys R14 | 2016 | France | 50, 12\38, 83 (7.8) | 50, 15\35, 85 (8) | B |

ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery.

Table 2.

Test data source and data extraction (length of stay (LOS)) of included studies

| Studies | Year | Country | Language | Surgical site | Total numbers | LOS (day) | ||

| ERAS | Non-ERAS | ERAS | Non-ERAS | |||||

| Auyong DB5 | 2015 | United States | English | TKA | 126 | 126 | 2.34±0.97 | 3.19±0.27 |

| Christelis N6 | 2015 | Australia | English | THA\TKA | 297 | 412 | 4.9±1.6 | 5.3±1.6 |

| denHertog A7 | 2012 | Germany | English | TKA | 74 | 73 | 6.75 | 13.2 |

| MaempelJF8 | 2015 | England | English | TKA | 84 | 81 | 3±2.14 | 4±2.16 |

| Malviya A9 | 2011 | England | English | THA\TKA | 1500 | 3000 | 4.8±3 | 8.5±6 |

| McDonald DA10 | 2012 | England | English | TKA | 1081 | 735 | 4±2 | 6±3 |

| Scott NB11 | 2013 | England | English | THA\TKA | 405 | 873 | 5 | 5 |

| Stambough JB12 | 2015 | United States | English | THA | 488 | 281 | 2±1 | 4±1 |

| Stowers MD13 | 2016 | New Zealand | English | THA\TKA | 100 | 100 | 4±2 | 5±2 |

| Talboys R14 | 2016 | France | English | THA | 50 | 50 | 8.5±9.4 | 7±11.2 |

ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Table 3.

Test data source and data extraction (incidence of complications)

| Studies | Year | Country | Language | Surgical site | Total number of cases | Total incidence of complications | ||||

| ERAS | Non-ERAS | ERAS | N% | Non-ERAS | N% | |||||

| Auyong DB5 | 2015 | United States | English | TKA | 126 | 126 | 3 | 2.38% | 7 | 5.56% |

| Christelis N6 | 2015 | Australia | English | THA\TKA | 297 | 412 | 30 | 10.1% | 49 | 11.89% |

| denHertog A7 | 2012 | Germany | English | TKA | 74 | 73 | 8 | 10.81% | 12 | 16.44% |

| MaempelJF 8 | 2015 | England | English | TKA | 84 | 81 | 3 | 3.57% | 5 | 6.17% |

| Malviya A9 | 2011 | England | English | THA\TKA | 1500 | 3000 | 39 | 2.6% | 103 | 3.43% |

| McDonald DA10 | 2012 | England | English | TKA | 1081 | 735 | 27 | 2.5% | 16 | 2.18% |

| Stowers MD13 | 2016 | New Zealand | English | THA\TKA | 100 | 100 | 15 | 15% | 22 | 22% |

ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Table 4.

Test data source and data extraction (30-day readmission rate)

| Studies | Year | Country | Language | Surgical site | Total number of cases | 30-day readmission rate | ||||

| ERAS | Non-ERAS | ERAS | N% | Non-ERAS | N% | |||||

| Auyong DB5 | 2015 | United States | English | TKA | 126 | 126 | 3 | 2.38% | 7 | 5.56% |

| Christelis N6 | 2015 | Australia | English | THA\TKA | 297 | 412 | 10 | 3.37% | 14 | 3.4% |

| Malviya A9 | 2011 | England | English | THA\TKA | 1500 | 3000 | 70 | 4.67% | 144 | 4.8% |

| Stambough JB12 | 2015 | United States | English | THA | 488 | 281 | 7 | 1.43% | 11 | 3.91% |

| Stowers MD13 | 2016 | New Zealand | English | THA\TKA | 100 | 100 | 8 | 8% | 14 | 14% |

ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Results of the meta-analysis

Comparison of postoperative LOS between the two groups

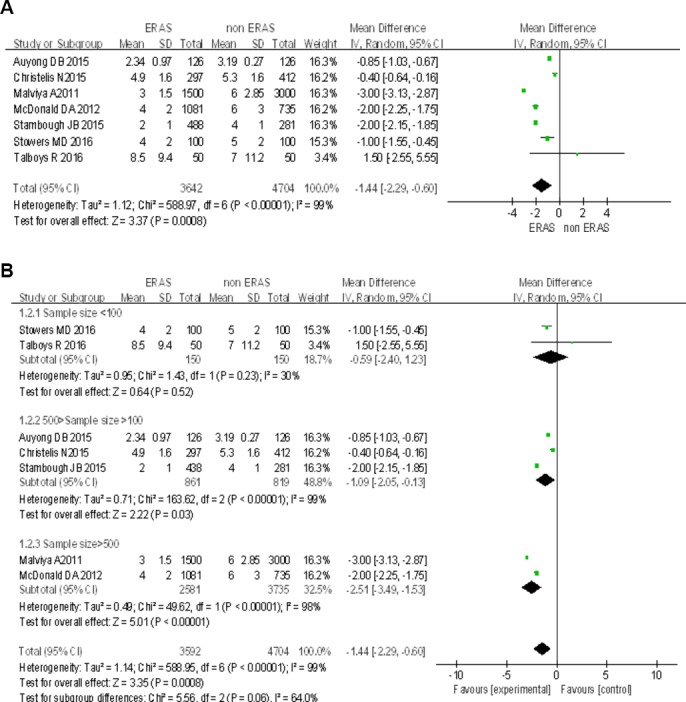

All 10 studies5–14 reported the LOS. However, since three studies did not provide standard deviation, 7 8 11 only providing time and range data, the date/data for the LOS in days of the other seven studies5 6 9 10 12–14 were collected/used instead of SD. There were a total of 8346 patients, including 3642 cases in the ERAS groups and 4704 cases in the control groups. Statistical heterogeneity was found among studies (I2=98%, p<0.01), and a random effect model was used. One study reported by Talboys14 indicated that there was no statistical difference in LOS between the two groups, yet despite this, the overall meta-analysis showed that ERAS significantly shortened LOS. The difference was statistically significant for comparison between the ERAS and control groups (SMD=−0.85, 95% CI=−1.24 to −0.45, p=0.01) (figure 2a). A subgroup analysis of the LOS between the ERAS and control groups is found in figure 2b.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the length of stay between the ERAS group and the control group. ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery.

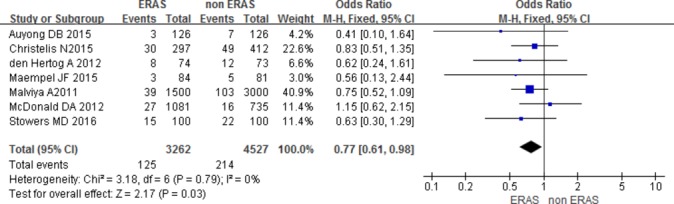

Comparison of incidence of postoperative complications between the two groups

Among the 10 cited investigation, seven5–10 13 reported postoperative complications. These involved 7789 patients including 3262 ERAS group cases and 4527 control group cases. Our preliminary review of the literature revealed a report by Stowers13 which indicated that no statistical difference was found between the ERAS group and the control group (p=0.372). However, data extracted from seven investigations, including the one published by Stowers,13 were re-analysed, and the results clearly show statistical differences in the incidence of complications between the two groups (OR=0.77, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.98; p=0.03; figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the incidence of complications between the ERAS group and the control group.

Comparison of 30-day readmission rates between the two groups

Among 10 studies selected, five5 6 9 12 13 reported 30-day readmission rates involving 6430 patients. This included 2511 ERAS group cases and 3919 control group cases. Data analysis shows no significant difference between the two groups in the incidence of 30-day readmissions (OR=0.84, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.08, p=0.18; figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of 30-day readmission rate between ERAS and control group.

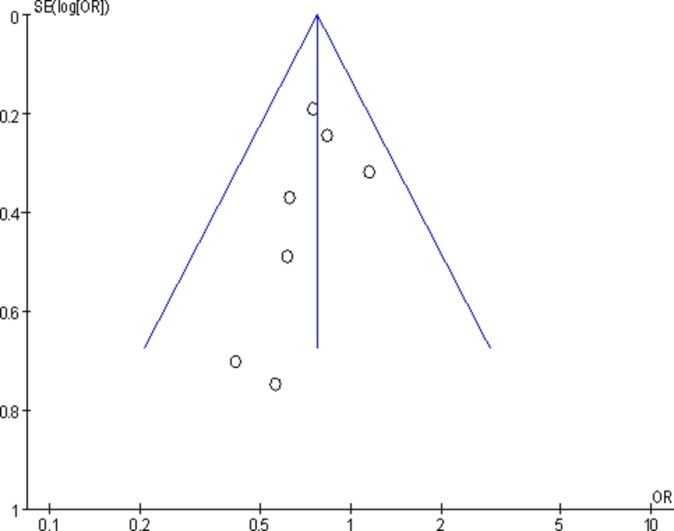

Publication bias

A funnel plot was performed with incidence of complications as the indicator. Seven points in the funnel plot, roughly distributed in an inverted funnel, suggest a lower impact of publication bias on the results (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Analysis of publication bias for postoperative complications from seven studies (funnel plot of standard error of log odds ratio vs odds ratio for the incidence of postoperative complications in ERAS group compared with non-ERAS group). ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery.

Comprehensive evaluation

Postoperative pain assessments in five studies5–8 10 show that ERAS groups achieved better analgesic results than non-ERAS groups: Auyong5 reported the VAS scores on the surgery day were 5.7 in the ERAS group and 4.5 in the non-ERAS group (p<0.01). VAS score decreased in both groups in the first 2 days after surgery and decreased thereafter. Yet even from the first day of recovery, Auyong reported differences in the amplitude of this increase between the two groups. On the first day after surgery, the VAS scores were 6.3 in the ERAS group and 7.1 in the non-ERAS group (p<0.01). On the second day, the VAS scores were 5.7 in the ERAS group and 6.3 in the non-ERAS group (p=0.03). There was no significant difference in VAS score on and after the third day. During the hospitalisation, the ERAS groups were superior to the non-ERAS groups in their ability to reduce the need for expensive opioid pain relievers and thus reduce hospitalisation costs.

Den Hertog7 reported that there was no significant difference in VAS scores between the two groups on the day of surgery. However, den Hertog did find statistical differences on the first day of recovery and again on days 5 through 7. The cumulative reduction-in-pain score was far more positive for patients in the ERAS group than for those in the non-ERAS group (p=0.0003). Maempel8 indicated that a significant difference was found in the VAS scores between the two groups (p<0.001); the ERAS group scores were superior to those of the non-ERAS group, while there was no significant difference in the amplitude of variation between the two groups (p=0.55). The demands for analgesic drugs were higher for all patients in the first 2 days of recovery. After that, 50% of the patients in the ERAS group had discontinued their use of analgesic drugs 41 days later whereas it took 71 days after surgery for those in the non-ERAS group to reach that same 50% benchmark. Christelis6 reported no difference in VAS scores between the two groups, but patients in the ERAS group had a higher degree of satisfaction at 6 weeks after surgery. Stowers’13 study included a comprehensive index of hospital costs. The average total costs for THA and TKA hospitalisation in New Zealand dollars were as follows: THA, ERAS $10 638.66 versus non-ERAS $13,216.89, p=0.057; TKA, ERAS $11 804.80 versus non-ERAS $12,045.35, p=0.326. There was no significant difference with the latter.

Discussion

After the introduction of the ERAS concept by Danish surgeon H. Kehlet in the 1990s, more and more studies demonstrated that ERAS is superior to traditional treatment in terms of safety and efficacy for various afflictions in the perioperative period.15

As our knowledge of the ERAS concept has grown, its applicability in increasing the safety and efficacy of postoperative care and recovery for patients undergoing orthopaedic arthroplasty has also grown. A large number of investigations report that LOS after arthroplasty can be reduced from 4–12 days to 1–3 days with no significant increase in the incidence of complications and readmissions.12 15–17 At the same time, studies show that ERAS can benefit the vast majority of patients receiving hip or knee arthroplasty, including older patients, patients with preoperative cardiopulmonary disease or type II diabetes, as well as those with complications due to tobacco, alcohol or other substance misuse issues.18 19 In addition, Khan et al 16 retrospectively analysed 1744 patients who underwent TKA and also received ERAS. They found that ERAS significantly shortened LOS, reduced reoperation rate, readmission rate and other aspects compared with the results of 1631 patients treated with traditional TKA. The study also found that transfusion rates and incidence of heart events were lower in the ERAS group than in the control group. Most studies have shown that ERAS was safe and effective, that it can speed up the patient’s recovery process, their reliance on costly pain medication, and that it improves patient satisfaction. More importantly, using ERAS saves valuable medical resources.

The case for the safety and efficacy of ERAS in THA and TKA seems overwhelmingly clear. But what specific changes in current practice do we need to implement? The changes needed in the current application of ERAS in the perioperative period of arthroplasty can be summarised as follows20: greater patient education; perioperative nutritional support; anaesthesia management: optimisation of anaesthesia, shortening fasting time,21 preoperative oral carbohydrate,22 early postoperative feeding, restrictive infusion23; minimally invasive surgery, i.e. the DAA approach,24 the medial vastus muscle approach;25 blood management: anaemia management, application of tranexamic acid,25 controlled hypotension; prevention of infection and venous thromboembolism; optimisation of analgesic regimen: preemptive analgesia, peripheral nerve block, local infiltration anaesthesia, postoperative multimode analgesia; optimised application of tourniquet, drainage tube and catheter; sleep management; prevention of nausea and vomiting; functional recovery exercise; and follow-up management after discharge.

Unfortunately, most surgeons generally focus on surgical technique alone, disregarding the perioperative management of patients altogether. The implementation of ERAS has not been sufficiently inculcated into the minds of every medical practitioner. In future medical work, we must follow evidence-based best practice, optimal medical models and ERAS under pathophysiology, but more importantly, all the staff need to actively commit to working together. This means everyone including surgeons, anaesthesiologists, nurses, nutritionists and physiotherapists. In addition, we need to obtain the support and understanding of patients. Only in this way can we get rid of the shackles of traditional ideas and achieve real enhanced recovery.

The meta-analysis included in the system showed that the application of ERAS can reduce hospital days (figure 2), but not increase complications and 30-day readmission rate (figures 3 and 4). The LOS in this paper had great heterogeneity, so we further analysed a subgroup of LOS, which showed that the sample size of the ERAS group and the control group is one of the causes of heterogeneity, and there were many other clinical reasons affecting LOS heterogeneity (including a variety of optimisation measures taken by ERAS). But we think that the result of LOS heterogeneity is significant: the aim of ERAS in the arthroplasty perioperative period is to reduce the hospitalisation time without increasing complications and readmission. Compared with the LOS of the non-ERAS group, the LOS of the ERAS groups included in the literature5 6 9 10 12–14 had different degrees of reductions in the perioperative period after a series of optimisation schemes for joint replacement, which was the main clinical cause for the heterogeneity. This would have guiding significance for the implementation of ERAS in the perioperative period of clinical joint replacement. In this paper, a meta-analysis was used to further elucidate the safety and efficacy of ERAS for patients receiving arthroplasty during the perioperative period, and to provide evidence-based medical evidence for best practice clinical work. We hope to further root the ERAS concept in the hearts of every medical practitioner for the benefit of all patients.

This is the first meta-analysis of ERAS in arthroplasty. We maximised the sample size by retrieving a large, powerful database from relevant studies that conformed to valid restrictions, including only RCT and CCT studies, ensuring the scientific reliability of the studies. But there were some limitations. This study had language restrictions, retrieving only studies published in English, so language or publication standards bias might exit. In addition, the number of truly high-quality studies eligible under these standards was too small. This might have caused bias in the final results. Some of the studies we rejected mentioned the word ‘random’ but did not describe the specific method employed, and did not mention whether a blind methodology was used or whether it had had any dropout or not, which might cause a certain degree of bias risk. However, with this analysis, we feel we have brought up to date the discussion about the role of existing surgical procedures in recovery approaches. It is through these evidence-based changes that we find a reduction in the complications of arthroplasty, a significant reduction in LOS, as well as multiple improvements after surgery.

Main messages.

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) is becoming a focus for clinical research.

There is no consensus on the effectiveness of ERAS.

This systematic review and meta-analysis estimates the efficacy and safety of ERAS in knee and hip arthroplasty.

Current research questions.

Enhanced recovery after surgery produces exciting clinical results in the field of orthopaedics, especially in joint surgery.

Most surgeons generally focus on surgical techniques but disregard the perioperative management of patients.

The effect of ERAS on arthroplasty does not form a unified opinion.

Acknowledgments

We thank the teachers of the Department of Orthopaedics, Beijing Union Medical College Hospital for giving advice on the article design, and thank He Hongmei of Henan University School of Medicine for providing guidance on design and statistical analysis. We appreciate the language polishing by native English speaker Pat Santee, thank you very much.

Footnotes

Contributors: ZS designed the study and developed the retrieve strategy. JC and YC performed the systematic evaluation as the first and second reviewers, searching and screening the summaries and titles, assessing the inclusion and exclusion criteria, generating data collection forms and extracting data, and evaluating the quality of the study. Professor QW advised and revised the inclusion/exclusion criteria. ZS and CX performed meta-analysis of continuous and skewed results (30 days re-admission rate, LOS and complications). ZS drafted the article. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Funding: Source: National Natural Science Foundation of China. Name: 3D-Printed Paramagnetic Titanium Alloy Scaffolds in the Repair of Osteonecrosis of Femoral Head: Insights of its mechanism and efficacy. Grant Number: 81572110.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data are available.

References

- 1. Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth 1997;78:606–17. 10.1093/bja/78.5.606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews ofInterventions. Version 5.0.2, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items forsystematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J ClinEpidemiol 2009;62:1006–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002 10.1136/bmj.d4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Auyong DB, Allen CJ, Pahang JA, et al. Reduced length of hospitalization in primary total knee arthroplasty patients using an updated enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) Pathway. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:1705–9. 10.1016/j.arth.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christelis N, Wallace S, Sage CE, et al. An enhanced recovery after surgery program for hip and knee arthroplasty. Med J Aust 2015;202:363–8. 10.5694/mja14.00601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. den Hertog A, Gliesche K, Timm J, et al. Pathway-controlled fast-track rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized prospective clinical study evaluating the recovery pattern, drug consumption, and length of stay. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012;132:1153–63. 10.1007/s00402-012-1528-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maempel JF, Walmsley PJ, Maempel JF, et al. Enhanced recovery programmes can reduce lengthof stay after total knee replacement withoutsacrificing functional outcome at one year. Ann R CollSurgEngl 2015;97:563–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Malviya A, Martin K, Harper I, et al. Enhanced recovery program for hip and knee replacement reduces death rate. Acta Orthop 2011;82:577–81. 10.3109/17453674.2011.618911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McDonald DA, Siegmeth R, Deakin AH, et al. An enhanced recovery programme for primary total knee arthroplasty in the United Kingdom--follow up at one year. Knee 2012;19:525–9. 10.1016/j.knee.2011.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scott NB, McDonald D, Campbell J, et al. The use of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) principles in Scottish orthopaedic units--an implementation and follow-up at 1 year, 2010-2011: a report from the musculoskeletal Audit, Scotland. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013;133:117–24. 10.1007/s00402-012-1619-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stambough JB, Nunley RM, Curry MC, et al. Rapid recovery protocols for primary total hip arthroplasty can safely reduce length of stay without increasing readmissions. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:521–6. 10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stowers MD, Manuopangai L, Hill AG, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery in elective hip and knee arthroplasty reduces length of hospital stay. ANZ J Surg 2016;86:475–9. 10.1111/ans.13538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Talboys R, Mak M, Modi N, et al. Enhanced recovery programme reduces opiate consumptionin hip hemiarthroplasty. Eur J OrthopSurgTraumatol 2016;26:177–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kehlet H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Lancet 2013;381:1600–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61003-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khan SK, Malviya A, Muller SD, et al. Reduced short-term complications and mortality following enhanced recovery primary hip and knee arthroplasty: results from 6,000 consecutive procedures. Acta Orthop 2014;85:26–31. 10.3109/17453674.2013.874925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. den Hartog YM, Mathijssen NM, Vehmeijer SB. Reduced length of hospital stay after the introduction of a rapid recovery protocol for primary THA procedures. Acta Orthop 2013;84:444–7. 10.3109/17453674.2013.838657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jørgensen CC, Kehlet H. Lundbeck Foundation Centre for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement Collaborative Group. Role of patient characteristics for fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth 2013;110:972–80. 10.1093/bja/aes505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jørgensen CC, Madsbad S, Kehlet H; Lundbeck Foundation Centre for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement Collaborative Group. Postoperative morbidity and mortalityin type-2 diabetics after fast-track primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg 2015;120:230–8. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. zongke Z, Xisheng W, tiebing Q, et al. Expert consensus in enhanced recovery after total hip and knee arthroplasty in China:perioperative management. Chinese Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2016;9:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Practice Guidelines for preoperative fasting and the Use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: Application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures. An updated report by the american society of anesthesiologists task force on preoperative fastingand the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration. Anesthesiology 2017;126:376–93. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith MD, McCall J, Plank L, et al. Preoperative carbohydrate treatment for enhancing recovery after elective surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;14:CD009161 10.1002/14651858.CD009161.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boldt J. Fluid management of patients undergoing abdominal surgery--more questions than answers. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2006;23:631–40. 10.1017/S026502150600069X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Melchior E. Grundriss der allgemeinen chirurgie: J. F. Bergmann, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ 2014;349:g4829 10.1136/bmj.g4829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]