Abstract

As an infectious fungus that affects the respiratory tract, Cryptococcus neoformans (C. neoformans) commonly causes asymptomatic pulmonary infection. C. neoformans may target the brain instead of the lungs and cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) in the early phase of infection; however, this is dependent on successful evasion of the host innate immune system. During the initial stage of fungal infection, a complex network of innate immune factors are activated. C. neoformans utilizes a number of strategies to overcome the anti-fungal mechanisms of the host innate immune system and cross the BBB. In the present review, the defensive mechanisms of C. neoformans against the innate immune system and its ability to cross the BBB were discussed, with an emphasis on recent insights into the activities of anti-phagocytotic and anti-oxidative factors in C. neoformans.

Keywords: Cryptococcus neoformans, innate immune system, antioxidants, blood-brain barrier, transmission mechanism

1. Introduction

Cryptococcus neoformans (C. neoformans) is the most common fungus to cause meningoencephalitis in the central nervous system (CNS) worldwide (1). Each year, an estimated 1 million cases of cryptococcal meningitis are reported, with a >60% mortality rate within the first 3 months of infection (2,3). C. neoformans is typically acquired by inhaling spores or desiccated yeast from the environment (3). Following an initial asymptomatic pulmonary infection, the organism is carried in the bloodstream and subsequently disseminated to target organs, including lung, skin and bone, which typically results in lymphocytic meningitis (2–9). Results from experimental mouse models and human cases of cryptococcal meningitis have indicated that C. neoformans infection may also spread to the brain (4–9). While the lungs are considered a common site of infection, C. neoformans predominantly targets the brain; however, this is dependent on its ability to overcome the innate immune system of the host and cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) in the initial phase of infection (10).

To defend against C. neoformans infection in the initial phase, the host employs several types of innate immune cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs) and neutrophils, which phagocytize invading fungi and generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitrogen species (RNS) and chlorine species to aid in host protection (11,12). In response to the host innate immune response, C. neoformans activates virulence factors, including polysaccharide capsules and melanin pigment, to resist phagocytosis and avoid clearance (13,14). Furthermore, C. neoformans induces the activation of antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalases, and the synthesis of antioxidants, such as glutathione (GSH), to adapt to oxidative attack (14,15). These anti-oxidative factors have been demonstrated to be important for ROS and RNS resistance, repair of damage caused by oxidative attack and survival in the host (13–15).

The present review summarized the current understanding of the anti-innate immune response strategies utilized by C. neoformans and the mechanism involved in cryptococcal BBB traversal.

2. Innate immune system

Innate immune responses restrict the growth and invasion of C. neoformans in mammalian hosts (16). Innate immune cells are the first cells to encounter fungi and are the primary effector cells in the destruction and clearance of cryptococcal infection (17–26) (Table I). Furthermore, the generation of oxidative products by phagocytic cells may directly destroy the invading fungi (12).

Table I.

Primary functions of host innate immune cells.

| Cells | Primary function | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|

| Macrophages | Phagocytosis, production of ROI, RNI, superoxide and nitric oxide | (17–20) |

| Neutrophils | Phagocytosis, production of ROI, RNI, myeloperoxidase, defensins 1–4 and lysozymes | (21–23) |

| Dendritic cells | Fungal internalization and destruction | (24) |

| Natural killer | Direct destruction | (25,26) |

ROI, reactive oxygen intermediates; RNI, reactive nitrogen intermediates.

Macrophages

Macrophages are critical phagocytic cells within the host innate immune system (17). Complement and mannose receptors on the surface of macrophages mediate the phagocytosis of C. neoformans (17). In addition, macrophages release high levels of reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI), reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI), superoxide and nitric oxide, which damage DNA and a number of chemical moieties (11). Furthermore, macrophages promote Th1-like responses to induce fungal clearance (18,19). However, C. neoformans is able to proliferate within the macrophage phagosome, and may pass between macrophages (18–20).

Neutrophils

Similar to macrophages, neutrophils capture and degrade pathogens and serve a specific role in the initiation of inflammation in response to infection (21). Neutrophils enhance granuloma formation to destroy C. neoformans by oxidative and non-oxidative mechanisms (21). Furthermore, a previous study indicated that myeloperoxidase, which is located primarily in neutrophils, produces a strong oxidant hypochlorous acid from hydrogen peroxide and chloride ions (22). This is another predominant mechanism that neutrophils use to defend against fungal infection (22). In addition, neutrophils contain defensins 1–4, which are cytotoxic to C. neoformans (23).

DCs and natural killer (NK) cells

DCs phagocytize C. neoformans via complement or anti-capsular antibody-mediated opsonization, which leads to fungal internalization and destruction, ultimately resulting in tumor necrosis factor-α secretion and DC activation (24). Once phagocytized, cryptococci are degraded through oxidative and non-oxidative mechanisms following passage through lysosomes (24). A previous study indicated that NK cells bind and inhibit the growth of C. neoformans in vitro and induce fungal clearance in mice (25). In addition, previous results suggest that NK cells may directly destroy C. neoformans when mediated by perforin (26).

3. Innate immune system evasion

C. neoformans has a number of established virulence factors, including polysaccharide capsules and melanin, which function as non-enzymatic factors that potently influence the overall pathogenicity and phagocytic resistance of C. neoformans (27). A variety of extracellular proteins, including phospholipases, proteases and ureases (27), and enzymatic components of the redox system, including thioredoxins (Trxs), glutaredoxins (Grxs), peroxiredoxin (Prxs) and catalases, serve as enzymatic factors for C. neoformans survival during innate immune attack (27–66) (Table II).

Table II.

Primary function of C. neoformans antioxidant factors against host innate immune cells.

| Antioxidant factor | Function against host innate immune cells | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharide capsules | Inhibition of phagocytosis and resistance to phagosome digestion | (27–34) |

| Melanins | Scavenging ROS and reactive nitrogen intermediates | (27,34–37) |

| Phospholipases | Promotion of survival and replication in macrophages | (38–40) |

| Proteinase | Promotion of replication in macrophages and damage to phagosomal membranes | (41,42) |

| Ureases | Scavenging nitrogen | (33–35,43–45) |

| Peroxiredoxins | Metabolism of peroxides and/or peroxynitrite | (46–48) |

| Thioredoxins, glutaredoxins | Metabolism of ROS, reduction of oxidized sulfhydryl groups and maintenance of cellular redox homeostasis | (46,49–54) |

| (46,49,58–60) | ||

| Superoxide dismutases | Conversion of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide | (15,61–63) |

| Catalases | Conversion of hydrogen peroxide to water and molecular oxygen | (64) |

| Cytochrome c peroxidases | Degradation of hydrogen peroxide | (65) |

| Alternative oxidase genes | Interaction with the classic oxidative pathway | (66) |

ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Roles of virulence factors in defense against the innate immune response

Polysaccharide capsules

The polysaccharide capsule, which is composed of 90–95% glucuronxylomannan and 5% galactoxylomannan, is among the most important virulence factors of C. neoformans that aids the fungus to avoid recognition and phagocytosis by host phagocytes (28). The capsule prevents the phagocytosis of C. neoformans and resists phagosome digestion to preserve C. neoformans survival (28,29). Once engulfed by macrophages, the C. neoformans capsule may release polysaccharides into vesicles surrounding the phagosome that accumulate in the host cell cytoplasm, which promotes macrophage dysfunction and lysis (29). In addition, the capsular material suppresses the migration of phagocytes (30), interferes with cytokine secretion (31), directly inhibits T-cell proliferation (32), induces macrophage apoptosis (33) and delays the maturation and activation of human DCs (34). By contrast, acapsular mutants of C. neoformans may be effectively recognized and induce pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion in macrophages (29).

Melanin

Melanin is a negatively charged, hydrophobic pigment that is located in the cell walls of C. neoformans, and serves a key role in virulence and survival (34). A melanin gene disruption study has indicated that wild-type melanin-producing C. neoformans are more virulent (34). Melanin is composed of aggregates of small particles or granules and exogenous substrates (34,35). In the natural environment, melanin protects fungi from ultraviolet light, high temperatures, freezing and thawing (36). The potent antioxidant activity of melanin provides protection against oxidant concentrations similar to those produced by stimulated macrophages (37). The oxidative burst that follows phagocytosis is an important mechanism by which immune effector cells mediate antimicrobial action, which suggests that melanin may enhance virulence by protecting fungal cells against immune system-stimulated oxidative attack (37).

Roles of extracellular proteins in defense against the innate immune response

Phospholipases

Phospholipases are a heterogeneous group of enzymes that cleave phospholipids to produce various biologically active compounds, which alter the infection microenvironment and may favor the survival of C. neoformans in the host (38). The action of phospholipases may result in the destabilization of membranes, cell lysis and release of lipid second messengers (39). The secretion of PLB has been reported to promote the survival and replication of C. neoformans in macrophages in vitro (38). In addition, a previous study demonstrated that disruption of the PLB1 gene led to reduced virulence in vivo and growth inhibition in a macrophage-like cell line (40).

Proteinase

Environmental and clinical isolates of C. neoformans possess proteinase activity that has been demonstrated to degrade host proteins, including collagen, elastin, fibrinogen, immune-globulins and complement factors (41). Replication of C. neoformans inside macrophages is accompanied by the production of enzymes, including proteinases and phospholipases, which damage the phagosomal membrane (42). Therefore, cryptococcal proteinases may cause tissue damage, providing nutrients to the pathogen and protection from the host.

Ureases

As a nitrogen-scavenging enzyme, urease catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea to ammonia and carbonate, and is an important virulence factor of C. neoformans (43). C. neoformans may utilize urease to invade the CNS via the BBB and cause life-threatening meningoencephalitis (43,44). A previous study suggested that urease promoted the sequestration of cryptococcal cells in the microvasculature of the brain, while urease-negative strains seldom penetrated the CNS or caused disease (45). Although the specific role of urease protein in BBB invasion is unknown, it has been suggested that the extracellular enzymatic degradation of urea to toxic ammonia may damage endothelial cells and lead to an increase in barrier permeability (33–35).

Roles of antioxidant systems in defense against the innate immune response

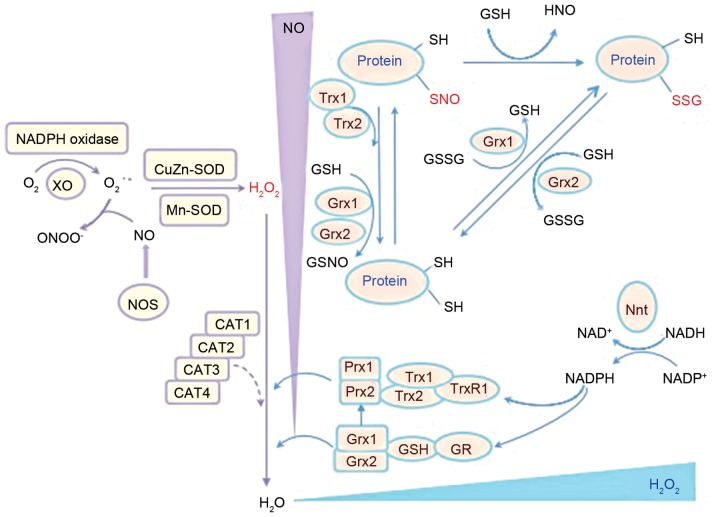

Resistance to RNS and ROS through antioxidant defense systems has been correlated with virulence in C. neoformans clinical isolates, and has been associated with in vitro and in vivo oxidative stress resistance (46). There are several enzymatic anti-oxidant systems that have been identified in C. neoformans, including the Prx, Trx and Grx systems (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the antioxidant chain of C. neoformans and the primary antioxidant enzymes involved. Prx, Trx and Grx systems are major enzymatic antioxidant systems in C. neoformans that regulate redox balance (49–51) that are associated with 2 SODs, Cu/Zn-SOD (SOD1) and Mn-SOD (SOD2), which may convert superoxide to hydrogen peroxide (61). C. neoformans, Cryptococcus neoformans; CAT, catalase; GR, glutathione reductase; Grx, glutaredoxin; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, glutathione disulfide; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; Nnt, nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; protein-SNO, protein nitrosylation; protein-SSG, protein glutathionylation; Prx1/2, peroxiredoxin 1/2; SH, thiol; SOD, superoxide dismutase; Trx, thioredoxin; TrxR, thioredoxin reductase.

Prx systems

The Prx system is important for cellular processes associated with disulfide bond formation, the anti-oxidative stress response and pathogenesis of C. neoformans infection (47). Prxs, also known as thiol peroxidases, are 20–30 kDa-sized molecules that provide antioxidant protection by removing peroxides (47). Prxs may be classified into 1-Cys and 2-Cys subgroups (48). Following peroxidation, typical 2-Cys Prxs form homodimers through an intersubunit disulfide bridge, whereas atypical 2-Cys Prxs form an intramolecular disulfide bridge (48). By contrast, 1-Cys Prxs assume a monomeric form with a single active cysteine site (48). In a previous study, two Prxs, TSA1 and TSA3, were discovered in C. neoformans, of which TSA1 is highly conserved (48). In addition, the findings of Missall et al (48) indicated that Prxs were induced under oxidative and nitrosative stress and were critical for C. neoformans virulence in mice. Furthermore, their study demonstrated that deletion of TSA1, but not TSA3, abolished virulence of the pathogen, which indicated that the TSA1-mediated Prx system is a core antioxidant system in C. neoformans (48).

Trx systems

The downstream component of Prx is the Trx system, which is comprised of NADPH, Trx and thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), and is involved in the regulation of DNA synthesis, gene transcription, cell growth and apoptosis (49–51). Trx is a small dithiol oxidoreductase that serves as a major carrier of redox potential in cells (52) and a cofactor for essential enzymes, and is involved in protein repair via methionine sulphoxide reductase (53) and the reduction of protein disulphides (54). This redox control of the Trx system is considered to regulate the expression of multiple stress defensive enzymes and protect cells against oxidative stress (54).

C. neoformans contains two Trx proteins (TRX1 and TRX2) and one TrxR protein (TRXR1) (50), which are involved in the reduction and recycling of the oxidized, inactive form of Prxs (55). TRX1 promotes normal growth and a healthy oxidative state (50,53). TRX2, though dispensable for vegetative growth, is important for resistance to nitrosative stress (50,53). TRXR1 is stimulated during oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide and nitrosative stress induced by nitric oxide (56). In C. neoformans, deletion of these genes renders them sensitive to oxidative stress and results in decreased survival in macrophage culture (50,57).

Grx systems

The GSH/Grxs system in C. neoformans is another major thiol-dependent antioxidant system that participates in the defense against oxidization (49). GSH is an important antioxidant for fungi. Strains that lack or possess altered GSH are sensitive to particular types of oxidative stress components, including peroxides, superoxide anions and the toxic products of lipid peroxidation (49). Exposure of yeast cells to hydrogen peroxide caused a reduction in GSH levels and a shift in the redox balance towards an oxidized state (49). In C. neoformans, Grxs are small heat-stable proteins encoded by two Grx genes (GRX1 and GRX2), and are reduced in a manner similar to Prx (49). GSH and Grxs may regulate protein function by reversible protein S-glutathionylation under oxidative stress (58). C. neoformans contains two glutathione peroxidases (GPX1 and GPX2) that respond differently to various stressors (59). A strain of C. neoformans that lacked the GRX1 gene was sensitive to oxidative stress induced by the superoxide anion, whereas a GRX2 mutant was sensitive to oxidative stress generated by hydrogen peroxide (59). Furthermore, GPX1 and GPX2 deletion mutants have been reported as only mildly sensitive to oxidant-induced destruction by macrophages and exhibited no change in virulence in a murine model (59). GPX1 and GPX2 are involved in the defense against organic peroxides, including tert-butyl hydroperoxide (59). Although both Gpx proteins are required for survival in macrophages, deletion of GPX1 and GPX2 does not affect the virulence of C. neoformans in mice (57), suggesting that other peroxidases or antioxidant systems may compensate for the loss. In addition, the GSH Prxs and GSH S-transferases are involved in the breakdown of organic hydroperoxides with GSH as a reductant or in the conjugation of toxic lipophilic compounds to GSH, respectively (60).

Additional antioxidant systems

The primary function of SOD is to convert superoxide to hydrogen peroxide (61). There are four classes of SODs: Mn, Fe, Ni and Cu/Zn (15). C. neoformans has two SODs, Cu/Zn-SOD (SOD1) and Mn-SOD (SOD2) (61). Cytosolic SOD1 has been demonstrated to serve a pivotal role in the defense against ROS and contributed to virulence in a mouse model (61). Furthermore, in a previous study, a C. neoformans SOD1 mutant strain exhibited slower growth in macrophages and greater susceptibility to neutrophil destruction (62). In addition, Narasipura et al (63) reported that a C. neoformans SOD1 mutant strain exhibited defects in phospholipase, urease and laccase expression, which severely attenuated virulence and the anti-phagocytotic activity of the pathogen.

Catalases are antioxidant metalloenzymes that promote the conversion of hydrogen peroxide to water and molecular oxygen (64). C. neoformans contains four catalases (CAT1, CAT2, CAT3 and CAT4), among which CAT2 and CAT4 are the closest orthologs of yeast CAT1 and CAT3 respectively (64). However, previous results have suggested that deletion of all four CAT genes did not affect the sensitivity to ROS or virulence of the pathogen (64), indicating that other peroxide-detoxifying systems may have a complementary role in C. neoformans. In addition, C. neoformans contains other enzymatic factors that protect against oxidative stress. For instance, cytochrome c peroxidase (CCP1) may degrade hydrogen peroxide (65). Furthermore, alternative oxidase gene (AOX1) is an enzyme that forms part of the electron transport chain in the mitochondria in C. neoformans, and its AOX1 mutant strain was demonstrated to be more sensitive to the oxidative stressor tert-butyl hydroperoxide; however, its target in the classic oxidative pathway remains unknown (66).

4. Traversal of the BBB

After surviving phagocytosis and oxidative attack initiated by the innate immune system, C. neoformans may be carried in the bloodstream and disseminated to target organs, including the brain (67,68).

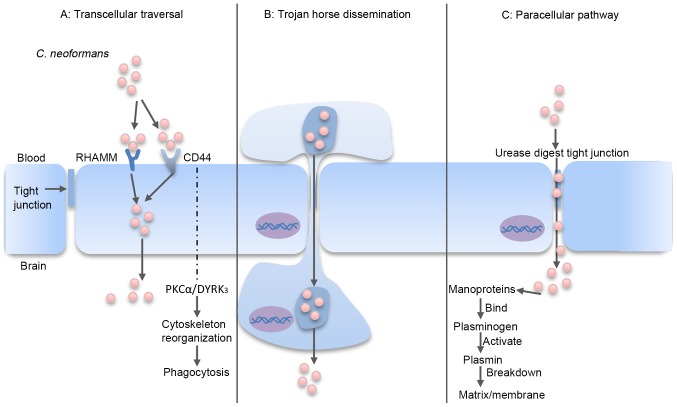

The BBB ensures that the brain is protected, and provides limited access to circulating macromolecules and microorganisms (67,68). In order to infect the brain, C. neoformans may use one of three potential traversal pathways to cross the BBB: Transcellular traversal, the paracellular pathway and Trojan horse dissemination (69–71) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

C. neoformans traversal of the BBB. (A) Transcellular traversal: C. neoformans binds to receptors on the endothelial cell, which triggers cellular endocytosis (72–79). (B) Trojan horse dissemination: C. neoformans is phagocytosed by a macrophage, which is able to cross the BBB, resulting in pathogen transportation into the brain (85–92). (C) Paracellular pathway: C. neoformans damages and weakens the intercellular tight junctions, which facilitates passage of the organism between the endothelial cells (80–82). RHAMM, receptor of hyaluronan-mediated motility; CD44, cluster of differentiation 44; PKCα, protein kinase Cα; DYRK3, dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 3; BBB, blood-brain barrier; C. neoformans, Cryptococcus neoformans.

Transcellular traversal

Transcellular traversal refers to the penetration of C. neoformans through barrier cells via the exploitation of cellular endocytosis (72,73). Transcellular traversal of the BBB has been widely studied using in vitro models, which have demonstrated an ability of C. neoformans to adhere to one or more receptors on the endothelial cell barrier (67,74).

Previous in vitro and in vivo results have demonstrated that the glycoprotein cluster of differentiation (CD)44 receptor on the surface of brain endothelial cells has a key role in transcellular traversal invasion of C. neoformans (75,76). CD44 is the endothelial cell receptor for hyaluronic acid, and is located in lipid rafts/caveolae on the endothelial cell surface (77,78). When hyaluronic acid in the C. neoformans capsule binds to CD44, a downstream signaling pathway mediated by protein kinase Cα and dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 3 is initiated, which triggers actin cytoskeleton reorganization and phagocytosis (5,71,79–81). Notably, Jong et al (79) documented that CD44−/− mice exhibited only a 2-fold reduction in cryptococcal meningitis compared with wild-type mice following intravenous injection of C. neoformans. Furthermore, knockdown of CD44 and the hyaluronan-mediated motility (RHAMM) receptor in mice conferred significantly higher protection and inhibited the invasion of C. neoformans in the brain when compared with knockdown of either receptor alone (79). These results suggest that CD44 and RHAMM serve as receptors for C. neoformans on the surface of brain endothelial cells through binding to hyaluronic acid. In addition, Maruvada et al (40) reported that C. neoformans PLB1 may interact with lipid mediators in the endothelial cell membrane of the brain to convert GDP-Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) to GTP-Rac1, which may then associate with signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (40). A recent study also indicated that metalloprotease 1, belonging to the M36 class of proteases, promoted the migration of C. neoformans across the brain endothelium and into the CNS by facilitating cryptococcal attachment to the endothelium surface, thus underscoring the critical role of M36 proteases in BBB permeation (80).

Paracellular pathway

The paracellular pathway involves the entry of C. neoformans through damaged or weakened tight junctions between the intercellular spaces of endothelial cells (81,82). Neuropil edema is a characteristic of endothelium damage (83,84), and sequestration of C. neoformans in the brain microvessels and cryptococcal binding to the endothelium has been demonstrated to induce tight junction alterations (83,84). In addition, cryptococcal mannoproteins bind and activate host plasminogens (82). Activated plasmins may subsequently bind and break down the extracellular matrix and membrane, which increases the likelihood of paracellular invasion (82).

A standard in vivo approach to investigate the mechanisms involved in the paracellular pathway is intravenous incubation of mice with C. neoformans and imaging of the blood vessels in the brain (67). Shi et al (71) imaged the cerebral blood vessels of mice infected with a fluorescently labeled C. neoformans urease mutant strain, and identified a markedly reduced capacity of the mutant to traverse to the brain (71). It is possible that urease participates in the enzymatic digestion of tight junctions between endothelial cells, and thus facilitates brain invasion via the transcellular route (43). Collectively, these findings indicate the possibility that C. neoformans uses a paracellular entry mechanism by weakening the brain endothelial tight junctions.

Trojan horse dissemination

The Trojan-horse dissemination of C. neoformans traversal involves the transport of pathogens into the brain within parasitized phagocytes (67,85). Previous results support the existence of a Trojan horse mechanism for BBB traversal (85). C. neoformans is a facultative intracellular pathogen that may survive and multiply inside phagocytes (86,87). Furthermore, C. neoformans may infect other phagocytes following their escape from phagocytic cells by vomocytosis, leaving the host macrophage unharmed (19,88). This direct cell-to-cell spread potentially explains how cryptococci may exploit phagocytes to penetrate the BBB in a Trojan horse manner (89). In previous studies, C. neoformans was identified inside phagocytes on the outer side of a meningeal capillary, which suggests that C. neoformans may have been transported within circulating phagocytes (90–92). These findings suggest that C. neoformans may use the Trojan-horse dissemination model to traverse into the brain.

5. Conclusions

The successful traversal of C. neoformans across the BBB relies on failure of the defense mechanisms imposed by the host innate immune system in the first phase of infection. Various innate immune constituents, including macrophages and neutrophils, contribute to phagocytosis, oxidative stress and clearance of C. neoformans (27). However, C. neoformans contains redundant layers of anti-phagocytic and anti-oxidative factors to resist the innate immune cells of the host, including polysaccharide capsules, melanin, phospholipases, proteases, ureases, TSA1, TSA3, TRX1, TRX2, TRXR1, GRX1, GRX2, GPX1, GPX2, SOD1, SOD2, CAT1, CAT2, CAT3, CAT4, CCP1 and AOX1.

Following its subversion of the innate immune response, C. neoformans may disseminate to the brain. However, entry into the highly protected environment of the brain requires C. neoformans to overcome the BBB. C. neoformans may gain entry through direct engulfment by endothelial cells (transcellular traversal), inducing damage to tight junctions (paracellular pathway) or hiding within phagocytes (Trojan-horse dissemination). Following successful evasion of the innate immune response, the fungi may proliferate (67). Results have indicated that >0.6 million cryptococcal meningitis cases each year result in mortality within 3 months of infection, even with treatment. In light of the present findings, the primary challenge in the field will be to obtain sufficient resources to identify Cryptococcus biomarkers for the improved determination of disease risk, treatment and prevention using therapies and vaccines, which may boost the immunity of the host to C. neoformans.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Nature Foundation of China (grant no. 81550028) received by Dr J. Wang, the Hubei Office of Education Foundation (grant nos. Q20151204 and B2016022) received by Dr LL. Zou and Dr J. Wang, and the Yi Chang Office of Healthcare Foundation (grant nos. A12301-25 and A16301-14) received by Mr CL. Yang and Dr J. Wang.

References

- 1.Loyse A, Thangaraj H, Eastervrook P, Ford N, Roy M, Chiller T, Govender N, Harrison TS, Bicanic T. Cryptococcal meningitis: Improving access to essential antifungal medicines in resource-poor countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:629–637. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beardsley J, Wolbers M, Kibengo FM, Ggayi AB, Kamali A, Cuc NT, Binh TQ, Chau NV, Farrar J, Merson L, et al. Adjunctive dexamethasone in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:542–554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang W, Fa Z, Liao W. Epidemiology of Cryptococcus and cryptococcosis in China. Fungal Genet Biol. 2015;78:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu TB, Kim JC, Wang Y, Toffaletti DL, Eugenin E, Perfect JR, Kim KJ, Xue C. Brain inositol is a novel stimulator for promoting Cryptococcus penetration of the blood-brain barrier. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003247. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jong A, Wu CH, Prasadarao NV, Kwon-Chung KJ, Chang YC, Ouyang Y, Shackleford GM, Huang SH. Invasion of Cryptococcus neoformans into human brain microvascular endothelial cells requires protein kinase C-alpha activation. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1854–1865. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panackal AA, Wuest SC, Lin YC, Wu T, Zhang N, Kosa P, Komori M, Blake A, Browne SK, Rosen LB, et al. Paradoxical immune responses in non-HIV Cryptococcal meningitis. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004884. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graciela Agar CH, Orozco Rosalba V, Macias Ivan C, Agnes F, Juan Luis GA, José Luis SH. Cryptococcal choroid plexitis an uncommon fungal disease. Case report and review. Can J Neurol Sci. 2009;36:117–122. doi: 10.1017/S0317167100006454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumari R, Raval M, Dhun A. Cryptococcal choroid plexitis: Rare imaging findings of central nervous system cryptococcal infection in an immunocompetent individual. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:e14–e17. doi: 10.1259/bjr/50945216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwerk C, Tenenbaum T, Kim KS, Schroten H. The choroid pleus-a multi-role player during infectious diseases of the CNS. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:80. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngamskulrungroj P, Chang Y, Sionov E, Kwon-Chung KJ. The primary target organ of Cryptococcus gattii is different from that of Cryptococcus neoformans in a murine model. MBio. 2012;3:e00103–e00112. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00103-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathan C, Shiloh MU. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen inter-mediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8841–8848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Almeida F, Wolf JM, Casadevall A. Virulence-associated enzymes of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2015;14:1173–1185. doi: 10.1128/EC.00103-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Jesús-Berríos M, Liu L, Nussbaum JC, Cox GM, Stamler JS, Heitman J. Enzymes that counteract nitrosative stress promote fungal virulence. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1963–1968. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon-Chung KJ, Fraser JA, Doering TL, Wang Z, Janbon G, Idnurm A, Bahn YS. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, the etiologic agents of cryptococcosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a019760. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Upadhya R, Campbll LT, Donlin MJ, Aurora R, Lodge JK. Global transcriptome profile of Cryptococcus neoformans during exposure to hydrogen peroxide induced oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voelz K, Lammas DA, May RC. Cytokine signaling regulates the outcome of intracellular macrophage parasitism by Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3450–3457. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00297-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redlich S, Ribes S, Schütze S, Eiffert H, Nau R. Toll-like receptor stimulation increases phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans by microglial cells. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:71. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chrisman CJ, Albuquerque P, Guimaraes AJ, Nieves E, Casadevall A. Phospholipids trigger Cryptococcus neoformans capsular enlargement during interactions with amoebae and macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002047. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alvarez M, Casadevall A. Cell-to-cell spread and massive vacuole formation after Cryptococcus neoformans infection of murine macrophages. BMC Immunol. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rohatgi S, Pirofski LA. Host immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:565–581. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mambula SS, Simons ER, Hastey R, Selsted ME, Levitz SM. Human neutrophil-mediated nonoxidative antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6257–6264. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.11.6257-6264.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winterbourn CC, Vissers MC, Kettle AJ. Myeloperoxidase. Curr Opin Hematol. 2000;7:53–58. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200001000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alcouloumre MS, Ghannoum MA, Ibrahim AS, Selsted ME, Edwards JE., Jr Fungicidal properties of defensin NP-1 and activity against Cryptococcus neoformans in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2628–2632. doi: 10.1128/AAC.37.12.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wozniak KL, Levitz SM. Cryptococcus neoformans enters the endolysosomal pathway of dendritic cells and is killed by lysosomal components. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4764–4771. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00660-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Islam A, Li SS, Oykhman P, Timm-McCann M, Huston SM, Stack D, Xiang RF, Kelly MM, Mody CH. An acidic microenvironment increases KN cell killing Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii by enhancing perforin degtanulation. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003439. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marr KJ, Jones GJ, Zheng C, Huston SM, Timm-McCann M, Islam A, Berenger BM, Ma LL, Wisenman JC, Mody CH. Cryptococcus neoformans directly stimulates perforin production and rearms NK cells for enhanced anticryptococcal microbicidal activity. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2436–2446. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01232-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodrigues ML, Nakayasu ES, Oliveira DL, Nimrichter L, Nosanchuk JD, Almeida IC, Casadevall A. Extracellular vesicles produced by Cryptococcus neoformans contain protein components associated with virulence. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:58–67. doi: 10.1128/EC.00370-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doering TL. How sweet it is! Cell wall biogenesis and polysaccharide capsule formation in Cryptococcus neoformans. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:223–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leopold Wager CM, Hole CR, Wozniak KL, Olszewski MA, Wormley FL., Jr STAT1 signaling is essential for protection against Cryptococcus neoformans infection in mice. J Immunol. 2014;193:4060–4071. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haynes BC, Skowyra ML, Spencer SJ, Gish SR, Williams M, Held EP, Brent MR, Doering TL. Toward an integrated model of capsule regulation in Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002411. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villena SN, Pinheiro RO, Pinheiro CS, Nunes MP, Takiya CM, Dosreis GA, Previato JO, Mendonça-Previato L, Freire-de-Lima CG. Capsular polysaccharides galactoxylomannan and glucuronoxylomannan from Cryptococcus neoformans induce macrophage apoptosis mediated by Fas ligand. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1274–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yauch LE, Lam JS, Levitz SM. Direct inhibition of T-cell responses by the Cryptococcus capsular polysaccharide glucuronoxylomannan. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e120. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lupo P, Chang YC, Kelsall BL, Farber JM, Pietrella D, Vecchiarelli A, Leon F, Kwon-Chung KJ. The presence of capsule in Cryptococcus neoformans influences the gene expression profile in dendritic cells during interaction with the fungus. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1581–1589. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01184-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chatterjee S, Prados-Rosales R, Itin B, Casadevall A, Stark RE. Solid-state NMR reveals the carbon-based molecular architecture of Cryptococcus neoformans fungal eumelanins in the cell wall. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:13779–13790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.618389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sundaram C, Shantveer GU, Umabala P, Lakshmi V. Diagnostic utility of melanin production by fungi: Study on tissue sections and culture smears with Masson-Fontana stain. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:217–222. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.134666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nosanchuk JD, Rosas AL, Lee SC, Casadevall A. Melanisation of Cryptococcus neoformans in human brain tissue. Lancet. 2000;355:2049–2050. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02356-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mauch RM, Cunha Vde O, Dias AL. The copper interference with the melanogenesis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2013;55:117–120. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652013000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santangelo R, Zoellner H, Sorrell T, Wilson C, Donald C, Djordjevic J, Shounan Y, Wright L. Role of extracellular phospholipases and mononuclear phagocytes in dissemination of cryptococcosis in a murine model. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2229–2239. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2229-2239.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evans RJ, Li Z, Hughes WS, Djordjevic JT, Nielsen K, May RC. Cryptococcal phospholipase B1 is required for intracellular proliferation and control of titan cell morphology during macrophage infection. Infect Immun. 2015;83:1296–1304. doi: 10.1128/IAI.03104-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maruvada R, Zhu L, Pearce D, Zheng Y, Perfect J, Kwon-Chung KJ, Kim KS. Cryptococcus neoformans phospholipase B1 activates host cell Rac1 for traversal across the blood-brain barrier. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:1544–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rawson RB. The site-2 protease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1828:2801–2807. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desalermos A, Tan X, Rajamuthiah R, Arvanitis M, Wang Y, Li D, Kourkoumpetis TK, Fuchs BB, Mylonakis E. A multi-host approach for the systematic analysis of virulence factors in Cryptococcus neoformans. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:298–305. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrow CA, Fraser JA. Is the nickel-dependent urease complex of Cryptococcus the pathogen's Achilles' heel? MBio. 2013;4:e00408–e00413. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00408-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh A, Panting RJ, Varma A, Saijo T, Waldron KJ, Jong A, Ngamskulrungroj P, Chang YC, Rutherford JC, Kwon-Chung KJ. Factors required for activation of urease as a virulence determinant in Cryptococcus neoformans. MBio. 2013;4:e00220–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00220-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olszewski MA, Noverr MC, Chen GH, Toews GB, Cox GM, Perfect JR, Huffnagle GB. Urease expression by Cryptococcus neoformans promotes microvascular sequestration, thereby enhancing central nervous system invasion. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1761–1771. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63734-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Breitenbach M, Weber M, Rinnerthaler M, Karl T, Breitenbach-Koller L. Oxidative stress in fungi: Its function in signal transduction, interaction with plant hosts, and lignocellulose degradation. Biomolecules. 2015;5:318–342. doi: 10.3390/biom5020318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toledano MB, Delaunay-Moisan A, Outten CE, Igbaria A. Functions and cellular copartmentation of the thioredoxin and glutathione pathways in yeast. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:1699–1711. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Missall TA, Pusateri ME, Lodge JK. Thiol peroxidase is critical for virulence and resistance to nitric oxide and peroxide in the fungal pathogen, Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:1447–1458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.03921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benhar M, Shytaj IL, Stamler JS, Savarino A. Dual targeting of the thioredoxin and glutathione systems in cancer and HIV. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:1630–1639. doi: 10.1172/JCI85339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Missall TA, Lodge JK. Function of thioredoxin proteins in Cryptococcus neoformans during stress or virulence and regulation by putative transcriptional modulators. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:847–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benhar M. Nitric oxide and the thioredoxin system: A complex interplay in redox regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1850:2476–2484. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Netto LE, Antunes F. The roles of peroxiredoxin and thioredoxin in hydrogen peroxide sensing and in signal transduction. Mol Cells. 2016;39:65–71. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu J, Holmgren A. The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;66:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoshioka J. Thioredoxin superfamily and its effects on cardiac physiology and pathology. Compr Physlol. 2015;5:513–530. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ianiri G, Idnurm A. Essential gene discovery in the basidiomycete Cryptococcus neoformans for antifungal drug target prioritization. MBio. 2015;6:e02334–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02334-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Missall TA, Lodge JK. Thioredoxin reductase is essential for viability in the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:487–489. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.2.487-489.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalinina EV, Chernov NN, Novivhkova MD. Role of glutathione transferase, and glutaredoxin in regulation of redox-dependent processes. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2014;79:1562–1583. doi: 10.1134/S0006297914130082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu J, Holmgren A. The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;66:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grant CM. Role of the glutathione/glutaredoxin and thioredoxin systems in yeast growth and response to stress conditions. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:533–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanschmann EM, Godoy JR, Berndt C, Hudemann C, Lilling CH. Thioredoxins, glutaredoxins, and peroxiredoxins-molecular mechanisms and health significance: From cofactors to antioxidants to redox signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:1539–1605. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Narasipura SD, Chaturvedi V, Chaturvedi S. Characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans variety gattii SOD2 reveals distinct roles of the two superoxide dismutases in fungal biology and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1782–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cox GM, Harrison TS, McDade HC, Taborda CP, Heinrich G, Casadevall A, Perfect JR. Superoxide dismutase influences the virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans by affecting growth within macrophages. Infect Immun. 2003;71:173–180. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.173-180.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Narasipura SD, Ault JG, Behr MJ, Chaturvedi V, Chaturvedi S. Characterization of Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) gene knock-out mutant of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii: Role in biology and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1681–1694. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giles SS, Stajich JE, Nichols C, Gerrald QD, Alspaugh JA, Dietrich F, Perfect JR. The Cryptococcus neoformans catalase gene family and its role in antioxidant defense. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1447–1459. doi: 10.1128/EC.00098-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giles SS, Perfect JR, Cox GM. Cytochrome c peroxidase contributes to the antioxidant defense of Cryptococcus neoformans. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Akhter S, McDade HC, Gorlach JM, Heinrich G, Cox GM, Perfect JR. Role of alternative oxidase gene in pathogenesis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5794–5802. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5794-5802.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vu K, Eigenheer RA, Phinney BS, Gelli A. Cryptococcus neoformans promotes its transmigration into the central nervous system by inducing molecular and cellular changes in brain endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 2013;81:3139–3147. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00554-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zou LL, Ma JL, Wang T, Yang TB, Liu CB. Cell-penetrating peptide-mediated therapeutic molecule delivery into the central nervous system. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2013;11:197–208. doi: 10.2174/1570159X11311020006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tseng HK, Liu CP, Price MS, Jong AY, Chang JC, Toffaletti DL, Betancourt-Quiroz M, Frazzitta AE, Cho WL, Perfect JR. Identification of genes from the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans related to transmigration into the central nervous system. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stie J, Fox D. Blood-brain barrier invasion by Cryptococcus neoformans is enhanced by functional interactions with plasmin. Microbiology. 2012;158:240–258. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.051524-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shi M, Li SS, Zheng C, Jones GJ, Kim KS, Zhou H, Kubes P, Mody CH. Real-time imaging of trapping and urease-dependent transmigration of Cryptococcus neoformans in mouse brain. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1683–1693. doi: 10.1172/JCI41963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Charlier C, Chrétien F, Baudrimont M, Mordelet E, Lortholary O, Dromer F. Capsule structure changes associated with Cryptococcus neoformans crossing of the blood-brain barrier. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:421–432. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62265-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chang YC, Wang Z, Flax LA, Xu D, Esko JD, Nizet V, Baron MJ. Glycosaminoglycan binding facilitates entry of a bacterial pathogen into central nervous systems. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002082. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vu K, Weksler B, Romero I, Couraud PO, Gelli A. Immortalized human brain endothelial cell line HCMEC/D3 as a model of the blood-brain barrier facilitates in vitro studies of central nervous system infection by Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:1803–1807. doi: 10.1128/EC.00240-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jong A, Wu CH, Gonzales-Gomez I, Kwon-Chung KJ, Chang YC, Tseng HK, Cho WL, Huang SH. Hyaluronic acid receptor CD44 deficiency is associated with decreased Cryptococcus neoformans brain infection. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:15298–15306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.353375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jong A, Wu CH, Chen HM, Luo F, Kwon-Chuang KJ, Chang YC, Lamunyon CW, Plaas A, Huang SH. Identification and characterization of CPS1 as a hyaluronic acid synthase contributing to the pathogenesis of Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1486–1496. doi: 10.1128/EC.00120-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huang SH, Long M, Wu CH, Kwon-Chung KJ, Chang YC, Chi F, Lee S, Jong A. Invasion of Cryptococcus neoformans into human brain microvascular endothelial cells is mediated through the lipid rafts-endocytic pathway via the dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 3 (DYRK3) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:34761–34769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Long M, Huang SH, Shackleford GM, Jong A. Lipid raft/caveolae signaling is required for Cryptococcus neoformans invasion into human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Biomed Sci. 2012;19:19. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-19-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jong A, Wu CH, Shackleford GM, Kwon-Chung KJ, Chang YC, Chen HM, Quyang Y, Huang SH. Involvement of human CD44 during Cryptococcus neoformans infection of brain microvascular endothelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1313–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vu K, Tham R, Uhrig JP, Thompson GR, III, Pombejra Na S, Jamklang M, Bautos JM, Gelli A. Invasion of the central nervous system by Cryptococcus neoformans requires a secreted fungal metalloprotease. MBio. 2014;5:e01101–e1114. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01101-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim KS. Mechanisms of microbial traversal of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:625–634. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stie J, Bruni G, Fox D. Surface-associated plasminogen binding of Cryptococcus neoformans promotes extracellular matrix invasion. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Charlier C, Chrétien F, Lortholary O, Dromer F. Early capsule structure changes associated with Cryptococcus neoformans crossing of the blood-brain barrier. Med Sci (Paris) 2005;21:685–687. doi: 10.1051/medsci/2005218-9685. (In French) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen SH, Stins MF, Huang SH, Chen YH, Kwon-Chung KJ, Chang Y, Kim KS, Suzuki K, Jong AY. Cryptococcus neoformans induces alterations in the cytoskeleton of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:961–970. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Charlier C, Nielsen K, Daou S, Brigitte M, Chretien F, Dromer F. Evidence of a role for monocytes in dissemination and brain invasion by Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2009;77:120–127. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01065-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alvarez M, Casadevall A. Phagosome extrusion and host-cell survival after Cryptococcus neoformans phagocytosis by macrophages. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2161–2165. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Coelho C, Souza AC, Derengowski Lda S, de Leon-Rodriguez C, Wang B, Leon-Rivera R, Bocca AL, Gonçalves T, Casadevall A. Macrophage mitochondrial and stress response to ingestion of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 2015;194:2345–2357. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sorrell TC, Juillard PG, Djordjevic JT, Kaufman-Francis K, Dietman A, Milonig A, Combes V, Grau GE. Cryptococcal transmigration across a model brain blood-barrier: Evidence of the Trojan horse mechanism and differences between Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii strain H99 and Cryptococcus gattii strain R265. Microbes Infect. 2016;18:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ma H, Croudace JE, Lammas DA, May RC. Direct cell-to-cell spread of a pathogenic yeast. BMC Immunol. 2007;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Davis MJ, Eastman AJ, Qiu Y, Greorka B, Kozel TR, Osterholzer JJ, Curtis JL, Swanson JA, Olszewski MA. Cryptococcus neoformans-induced macrophage lysosome damage crucially contributes to fungal virulence. J Immunol. 2015;194:2219–2231. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu TB, Perlin DS, Xue C. Molecular mechanisms of cryptococcal meningitis. Virulence. 2012;3:173–181. doi: 10.4161/viru.18685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Alanio A, Vernel-Pauillac F, Sturny-Leclère A, Dromer F. Cryptococcus neoformans host adaptation: Toward biological evidence of dormancy. MBio. 2015;6:e02580–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02580-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]