Abstract

Ascites is among the most common complications of liver cirrhosis and is associated with a high mortality rate. The present retrospective study aimed to evaluate the potential correlation between in-hospital mortality of liver cirrhosis and volume of ascites. Patients with liver cirrhosis who were admitted to the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region (Shenyang, China) between June 2012 and June 2014 and underwent axial abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT) scans were retrospectively reviewed. The volume of ascites was approximated using a five-point method, and diagnostic accuracy was expressed by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUROCs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Of the 177 patients reviewed in the present study, 117 (61.10%) exhibited ascites on CT scans, and the in-hospital mortality rate was 4.52% (8/177). Child-Pugh and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores were significantly increased in the presence of ascites (P<0.001). The in-hospital mortality rate did not differ significantly between patients with and without ascites (P=0.052). In patients with ascites >300 ml (n=72), the AUROCs of the Child-Pugh score, MELD score, and ascites volume for predicting in-hospital mortality were 0.939 (95% CI, 0.856–0982), 0.952 (95% CI, 0.873–0.988), and 0.782 (95% CI, 0.668–0.871), respectively. These AUROCs did not differ significantly. In conclusion, quantification of ascites may aid to predict the in-hospital mortality rate of cirrhotic patients.

Keywords: ascites, prognosis, five-point method, cirrhosis, in-hospital mortality

Introduction

Liver cirrhosis is an end-stage complication of chronic liver diseases (1). Ascites is among the most common complications of cirrhosis, and >60% of cirrhotic patients develop ascites within 10 years of the diagnosis of cirrhosis (2). Ascites is typically the primary sign of portal hypertension in decompensated liver cirrhosis (3). The appearance of ascites is associated with poor prognosis, and previous results suggest that the 1- and 2-year mortality rate of cirrhotic patients with ascites is 50 and 60%, respectively (4). In patients with ascites, more severe complications, including hepatorenal syndrome and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, may be induced, thereby increasing the risk of mortality (5–8).

The treatment strategy of ascites is primarily based on the grade of ascites, according to guidelines of the International Ascites Club (5,6). The grade of ascites is principally based on physical examinations and ultrasound (5). However, to the best of our knowledge, no method for the quantification of ascites in liver cirrhosis has previously been reported. Strategies to determine the volume of ascites may be important for the prognostic assessment of liver cirrhosis.

Oriuchi et al (9) developed a simple and accurate ‘five-point’ method of measuring the volume of ascites in patients with malignant ascites, which utilized standard abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT). Oriuchi et al (9) demonstrated that conventional CT might be an alternative method for measuring the thickness of ascites, while three-dimensional CT (3D-CT) was optimal for measuring precise ascites volumes. Notably, a statistically significant correlation was identified between the exact volume measured by 3D-CT and the volume estimated by the five-point method (r=0.956, P<0.01). Subsequent studies have verified the accuracy of the five-point method (10,11).

In the present retrospective study, the five-point method was used to evaluate the volume of ascites and its association with liver dysfunction severity and in-hospital mortality rate of patients with liver cirrhosis.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

The present study was a retrospective observational study of patients' medical records. Patients diagnosed with liver cirrhosis at the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region (Shenyang, China) from June 2012 to June 2014 were eligible. Patients who underwent abdomino-pelvic CT scans during hospitalization were included. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) hepatocellular carcinoma or any other kind of malignancy; and ii) patients' medical records or laboratory test results were lacking. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region (approval no. k/2015/41). Written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data collection

The volume of ascites was calculated using the five-point method (9). Five variables, namely total bilirubin (TBIL), albumin (ALB), international normalized ratio (INR), hepatic encephalopathy, and ascites were used to calculate the Child-Pugh class/score, as previously described (12). The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was also calculated according to the following formula: 9.57 × loge[creatinine (µmol/l) × 0.01] + 3.78 × loge[TBIL (µmol/l) × 0.05] + 11.2 × loge(INR) + 6.43, as previously described (13,14).

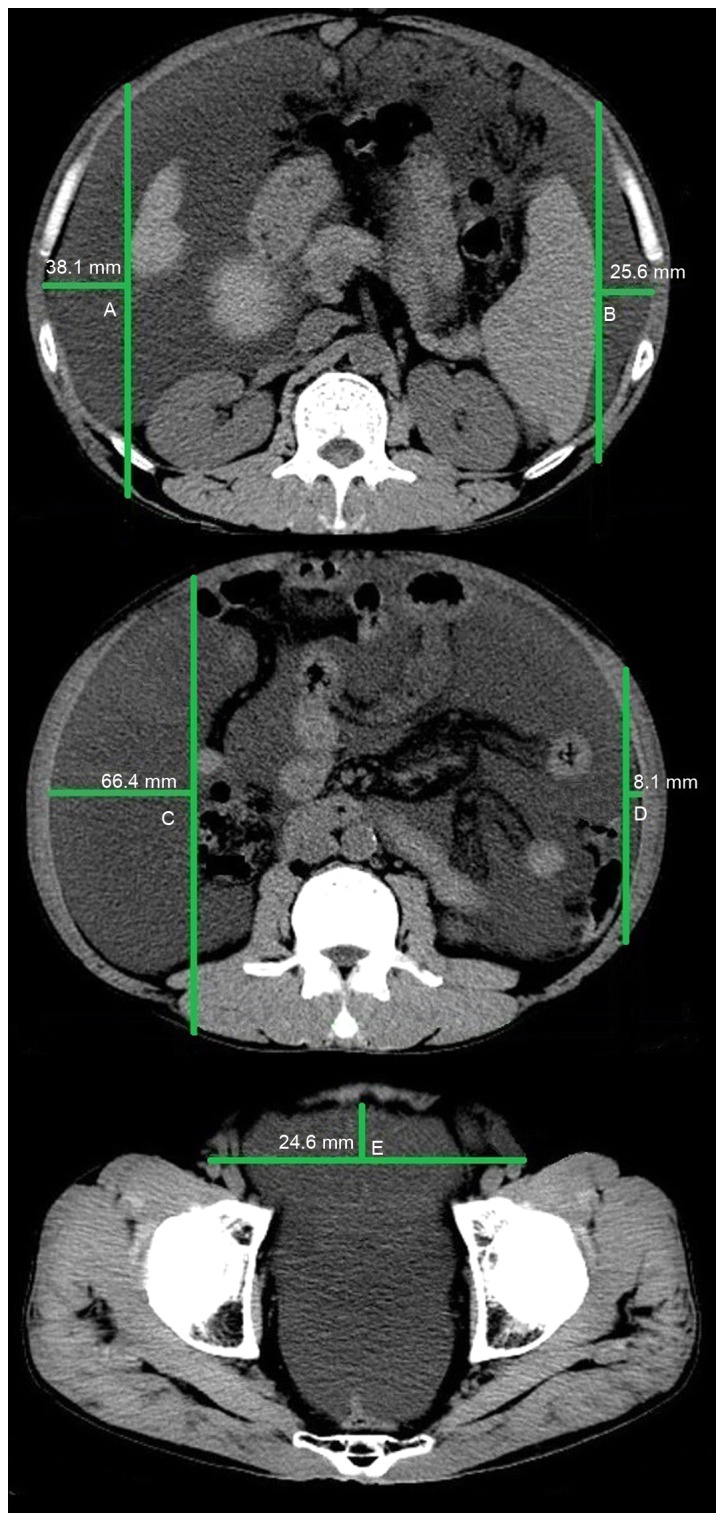

Five-point method

All CT images were reviewed by two investigators (a resident and an attending physician) together using a PowerRIS system version 5.0 (Mozi Healthcare Technology, Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) at the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region. The method of measuring ascites on a CT image is outlined in Fig. 1. Three specified planes were selected to quantify the volume of ascites. The first plane was the superior mesenteric artery branch from the abdominal aorta. The distance between the inner surface of the right abdominal wall at antero-posterior mid portion and the surface of the liver was denoted as A (cm); the distance between the inner surface of the left abdominal wall at antero-posterior mid portion and the surface of the spleen was denoted as B (cm). If the liver was not observed in this plane, the distance between the inner surface of the right abdominal wall and the internal organs was denoted as A. Similarly, if the spleen was not observed in this plane, the distance between the inner surface of the left abdominal wall and the internal organs was denoted as B. The second plane was the lower pole of the left kidney. The distance between the inner surface of the right abdominal wall at antero-posterior mid portion and the vertical line through the posterior pole of the right ascending colon was denoted as C (cm); the distance between the inner surface of the left abdominal wall at antero-posterior mid portion and the vertical line through the posterior pole of the descending colon was denoted as D (cm). The third plane was the femoral head. The distance between the inner surface of the anterior abdominal wall to the line though the bilateral femoral arteries was denoted as E (cm). The following equation was used to calculate the volume of ascites: (A+B+C+D+E) × 200 ml, as previously described (9). As only a small amount of peritoneal fluid was observed around the surface of the liver in patients with mild ascites, the volume of ascites measured by the five-point method was 0 ml, thus yielding a false negative for the presence of ascites.

Figure 1.

Measurement of the volume of ascites in abdomino-pelvic computed tomography images by the five-point method in the first (top image), second (middle image) and third (bottom image) planes.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and median and range, and were compared using a Student's t-test. Categorical variables were expressed as a frequency (percentage) and were compared using a χ2 test. The clinical characteristics, laboratory data, Child-Pugh and MELD scores, and in-hospital mortality were compared between patients with and without ascites. The five-point method has a higher accuracy in estimating the volume of ascites when the volume of ascites is >300 ml (9). Therefore, the clinical characteristics and outcomes were also compared between patients with an ascites volume >300 ml and those without ascites. Pearson correlation analysis was performed and the correlation between in-hospital mortality and volume of ascites was analyzed in patients with ascites >300 ml. The diagnostic accuracy of Child-Pugh and MELD scores and ascites volume was evaluated using area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUROCs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). MedCalc software version 11.4.2.0 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium) was used. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patients

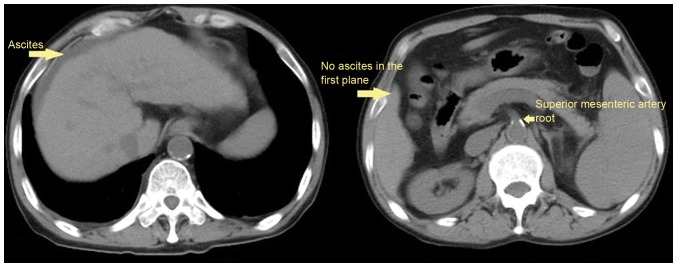

The data of 177 patients was reviewed in the present study. A total of 109 (61.58%) patients were male and 68 (38.42%) were female. The mean age of patients was 59.37±12.05 years. Ascites was confirmed by CT scans in 117 (61.10%) patients, among them, 27 patients presented with ascites, but the volume of ascites could not be evaluated according to five-point method (Fig. 2); and the volume of ascites was <300 ml in 45 patients. During hospitalization, the mortality rate of patients was 4.5% (8/177). Hepatitis B virus and alcohol abuse were the two major causes of cirrhosis. The patient characteristics are presented in Table I.

Figure 2.

An example demonstrating that a patient was not eligible for the evaluation of ascites volume by a five-point method. A cirrhotic patient exhibited mild ascites on the surface of liver (left). However, the volume of ascites could not be estimated by the five-point method due to the absence of ascites in the first plane (right).

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of patients.

| Variables | N | Mean ± SD or frequency (percentage) | Median (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male/female | 177 | 109 (61.58)/68 (38.42) | |

| Age, years | 177 | 59.37±12.05 | 58.00 (27.00–87.00) |

| Causes of liver diseases, n (%) | 177 | ||

| Hepatitis B virus | 43 (24.29) | ||

| Hepatitis C virus | 15 (8.47) | ||

| Hepatitis B virus + hepatitis C virus | 3 (1.69) | ||

| Alcohol | 45 (25.42) | ||

| Hepatitis B virus + alcohol | 17 (9.60) | ||

| Hepatitis C virus + alcohol | 1 (0.56) | ||

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 10 (5.65) | ||

| Drug induced liver disease | 5 (2.82) | ||

| PBC | 5 (2.82) | ||

| Unknown | 32 (18.08) | ||

| Autoimmune hepatitis + PBC | 1 (0.56) | ||

| Laboratory tests | |||

| RBC, 1012/l | 176 | 3.14±0.80 | 3.02 (1.01–5.57) |

| Hb, g/l | 176 | 96.51±228.58 | 96.00 (27.00–166.00) |

| WBC, 1012/l | 176 | 5.76±4.09 | 4.40 (1.00–26.00) |

| PLT, 109/l | 176 | 107.60±79.54 | 84.00 (13.00–463.00) |

| TBIL, µmol/l | 177 | 39.69±58.63 | 20.90 (2.00–446.30) |

| ALB, g/l | 176 | 30.58±6.19 | 30.00 (14.30–48.40) |

| ALT, U/l | 176 | 38.44±46.29 | 27.00 (5.00–368.00) |

| AST, U/l | 176 | 62.93±110.65 | 37.00 (8.00–1293.00) |

| ALP, U/l | 176 | 112.71±89.62 | 86.00 (17.00–531.00) |

| GGT, U/l | 176 | 103.20±146.83 | 48.00 (9.00–912.00) |

| BUN, mmol/l | 175 | 8.50±7.31 | 6.11 (1.63–61.88) |

| CR, µmol/l | 175 | 92.57±118.33 | 58.20 (27.40–857.00) |

| Serum potassium, mmol/l | 175 | 4.11±0.70 | 4.05 (1.90–7.24) |

| Serum sodium, mmol/l | 175 | 137.54±4.91 | 138.50 (121.00–146.40) |

| Serum calcium, mmol/l | 106 | 2.07±0.23 | 2.12 (1.06–2.66) |

| BA, µmol/l | 106 | 53.24±48.45 | 43.00 (9.00–415.00) |

| PT, sec | 177 | 17.07±8.05 | 15.40 (11.30–94.60) |

| APTT, sec | 177 | 44.46±13.66 | 42.60 (28.00–180.00) |

| INR | 177 | 1.44±1.13 | 1.23 (0.84–13.4) |

| In-hospital mortality | 177 | 8 (4.52) | |

| Child-Pugh score | 175 | 8.01±1.93 | 8.00 (5.00–14.00) |

| MELD score | 174 | 8.12±8.51 | 6.67 (−5.22–51.64) |

ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BA, blood ammonia; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CR, creatinine; GGT, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase; Hb, hemoglobin; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; PLT, platelet; PT, prothrombin time; RBC, red blood cell; SD, standard deviation; TBIL, total bilirubin; WBC, white blood cell.

Clinical characteristics of patients with and without ascites

Clinical characteristics were compared between patients with and without ascites (Table II). Significantly increased levels of TBIL (P=0.005), blood urea nitrogen (BUN; P<0.001), prothrombin time (PT; P=0.006), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT; P=0.014), INR (P=0.014), Child-Pugh (P<0.001), and MELD scores (P<0.001) were observed. A significant decrease in the level of red blood cell (RBC; P<0.001), hemoglobin (Hb; P=0.018), ALB (P<0.001), and serum sodium (P=0.002) was associated with the presence of ascites. All patients who did not survive during their hospitalizations presented with ascites; however, the in-hospital mortality between patients with and without ascites did not differ significantly (8/117 vs. 0/60, P=0.052).

Table II.

Comparison between patients with and without ascites.

| With ascites | Without ascites | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | Mean ± SD or frequency (percentage) | Median (range) | N | Mean ± SD or frequency (percentage) | Median (range) | P-value |

| Sex, male/female | 117 | 72 (61.54)/45 (38.46) | 60 | 37 (61.67)/23 (38.33) | 0.931 | ||

| Age, years | 117 | 59.58±12.18 | 57.00 (27.00–87.00) | 60 | 59.18±11.91 | 60.00 (34.00–84.00) | 0.756 |

| Causes of liver diseases, n (%) | 117 | 60 | |||||

| Hepatitis B virus | 24 (20.51) | 19 (31.67) | 0.175 | ||||

| Hepatitis C virus | 12 (10.26) | 3 (5.00) | 0.344 | ||||

| Hepatitis B virus + hepatitis C virus | 3 (2.56) | 0 (0.00) | 0.514 | ||||

| Alcohol | 29 (24.79) | 16 (26.67) | 0.814 | ||||

| Hepatitis B virus + alcohol | 13 (11.11) | 4 (6.67) | 0.467 | ||||

| Hepatitis C virus + alcohol | 1 (0.85) | 0 (0.00) | 0.743 | ||||

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 6 (5.13) | 4 (6.67) | 0.97 | ||||

| Drug induced liver disease | 3 (2.56) | 2 (3.33) | 0.832 | ||||

| PBC | 5 (4.27) | 0 (0.00) | 0.243 | ||||

| Unknown | 20 (17.09) | 12 (20.00) | 0.752 | ||||

| Autoimmune hepatitis + PBC | 1 (0.85) | 0 (0.00) | 0.743 | ||||

| Laboratory tests | |||||||

| RBC, 1012/l | 116 | 3.00±0.75 | 2.98 (1.01–5.40) | 59 | 3.42±0.83 | 3.39 (1.97–5.57) | <0.001 |

| Hb, g/l | 117 | 93.01±26.89 | 96.00 (27.00–151.00) | 59 | 103.84±30.71 | 102.00 (52.00–166.00) | 0.018 |

| WBC, 1012/l | 116 | 6.11±4.49 | 4.60 (1.30–26.00) | 59 | 4.98±3.09 | 4.20 (1.00–17.40) | 0.056 |

| PLT, 109/l | 116 | 102.01±77.59 | 74.00 (13.00–366.00) | 59 | 114.66±81.72 | 91.00 (19.00–463.00) | 0.318 |

| TBIL, µmol/l | 117 | 46.77±69.81 | 20.65 (2.00–446.30) | 59 | 26.69±20.87 | 20.60 (4.40–91.00) | 0.005 |

| ALB, g/l | 117 | 28.86±5.65 | 28.45 (14.30–48.40) | 59 | 34.00±5.84 | 34.80 (22.40–45.90) | <0.001 |

| ALT, U/l | 117 | 39.85±45.66 | 27.00 (8.00–323.00) | 59 | 35.63±47.78 | 27.00 (5.00–368.00) | 0.57 |

| AST, U/l | 117 | 69.59±127.12 | 42.00 (8.00–1293.00) | 59 | 49.73±66.04 | 29.00 (12.0–427.00) | 0.174 |

| ALP, U/l | 117 | 118.96±94.94 | 94.50 (17.00–531.00) | 59 | 100.31±77.30 | 80.00 (20.00–518.00) | 0.194 |

| GGT, U/l | 117 | 102.90±145.60 | 49.00 (9.00–912.00) | 59 | 103.78±150.48 | 45.00 (10.00–755.00) | 0.97 |

| BUN, mmol/l | 115 | 9.77±8.43 | 7.30 (1.77–61.88) | 60 | 6.05±3.35 | 5.33 (1.63–21.70) | <0.001 |

| CR, µmol/l | 115 | 110.63±141.87 | 63.00 (31.00–857.00) | 60 | 57.97±23.49 | 54.00 (27.40–164.00) | <0.001 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/l | 117 | 4.12±0.79 | 4.02 (2.46–7.24) | 58 | 4.07±0.46 | 4.07 (3.23–5.90) | 0.611 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/l | 117 | 136.71±5.03 | 137.90 (121.00–145.80) | 58 | 139.19±4.23 | 139.70 (125.50–146.40) | 0.002 |

| Serum calcium, mmol/l | 76 | 2.06±0.23 | 2.10 (1.40–2.66) | 30 | 2.11±0.25 | 2.17 (1.73–2.47) | 0.283 |

| BA, µmol/l | 77 | 56.65±53.37 | 43.50 (9.00–415.00) | 29 | 44.17±30.90 | 32.00 (9.00–107.00) | 0.139 |

| PT, sec | 117 | 17.99±9.54 | 15.70 (11.30–94.60) | 60 | 15.28±3.07 | 14.25 (11.70–31.60) | 0.006 |

| APTT, sec | 117 | 45.91±15.92 | 44.15 (28.00–180.00) | 60 | 41.64±6.78 | 40.20 (28.00–58.00) | 0.014 |

| INR | 117 | 1.56±1.37 | 1.27 (0.84–13.4) | 60 | 1.22±0.34 | 1.11 (0.84–3.06) | 0.014 |

| In-hospital mortality | 117 | 8 (6.84) | 60 | 0 (0.00) | 0.052 | ||

| Child-Pugh score | 117 | 8.88±1.56 | 9.00 (6.00–14.00) | 58 | 6.22±1.28 | 6.00 (5.00–10.00) | <0.001 |

| MELD score | 115 | 10.21±9.07 | 8.54 (−5.22–51.64) | 59 | 4.03±5.34 | 3.59 (−4.83–23.23) | <0.001 |

| Ascites volume, ml (according to five-point method) | 117 | 1,423.79±1,644.77 | 722.00 (0.00–7,070.00) | ||||

ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BA, blood ammonia; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CR, creatinine; GGT, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase; Hb, hemoglobin; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; PLT, platelet; PT, prothrombin time; RBC, red blood cell; SD, standard deviation; TBIL, total bilirubin; WBC, white blood cell.

Clinical characteristics of patients with ascites >300 ml and those without ascites

Clinical characteristics were compared between patients with ascites >300 ml (n=72) and those without ascites (n=60; Table III). Significantly increased levels of TBIL (P=0.019), BUN (P=0.0002), creatinine (P=0.002), PT (P=0.006), APTT (P=0.016), INR (P=0.014), and Child-Pugh (P<0.001) and MELD scores (P<0.001) were observed. Significantly decreased levels of RBC (P=0.001), Hb (P=0.009), ALB (P<0.001), and serum sodium (P=0.004) were also associated with ascites >300 ml. All patients who did not survive during their hospitalizations had ascites; however, the in-hospital mortality rate between patients with ascites >300 ml and those without did not differ significantly (5/72 vs. 0/60; P=0.081).

Table III.

Comparison between patients with ascites (>300 ml) and patients without ascites.

| With ascites (>300 ml) | Without ascites | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | Mean ± SD or frequency (percentage) | Median (range) | N | Mean ± SD or frequency (percentage) | Median (range) | P-value |

| Sex, male/female | 72 | 44 (61.11)/28 (38.89) | 60 | 37 (61.67)/23 (38.33) | 0.838 | ||

| Age, years | 72 | 58.13±12.19 | 55.50 (27.00–84.00) | 60 | 59.18±11.91 | 60.00 (34.00–84.00) | 0.686 |

| Causes of liver diseases, n (%) | 72 | 60 | 0.961 | ||||

| Hepatitis B virus | 13 (18.06) | 19 (31.67) | 0.107 | ||||

| Hepatitis C virus | 10 (13.89) | 3 (5.00) | 0.158 | ||||

| Hepatitis B virus + hepatitis C virus | 3 (4.17) | 0 (0.00) | 0.311 | ||||

| Alcohol | 18 (25.00) | 16 (26.67) | 0.986 | ||||

| Hepatitis B virus + alcohol | 9 (12.50) | 4 (6.67) | 0.408 | ||||

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 3 (4.17) | 4 (6.67) | 0.804 | ||||

| Drug induced liver disease | 2 (2.78) | 2 (3.33) | 0.393 | ||||

| PBC | 3 (4.17) | 0 (0.00) | 0.311 | ||||

| Unknown | 10 (13.89) | 12 (20.00) | 0.482 | ||||

| Autoimmune hepatitis + PBC | 1 (1.39) | 0 (0.00) | 0.338 | ||||

| Laboratory tests | |||||||

| RBC, 1012/l | 71 | 2.94±0.76 | 2.97 (1.19–5.40) | 59 | 3.42±0.83 | 3.39 (1.97–5.57) | 0.001 |

| Hb, g/l | 71 | 90.35±27.26 | 92.00 (27.00–151.00) | 59 | 103.84±30.71 | 102.00 (52.00–166.00) | 0.009 |

| WBC, 1012/l | 71 | 5.68±4.59 | 4.40 (1.30–26.00) | 59 | 4.98±3.09 | 4.20 (1.00–17.40) | 0.311 |

| PLT, 109/l | 71 | 101.92±80.32 | 70.00 (15.00–366.00) | 59 | 114.66±81.72 | 91.00 (19.00–463.00) | 0.373 |

| TBIL, µmol/l | 72 | 50.10±79.89 | 19.90 (2.00–446.30) | 59 | 26.69±20.87 | 20.60 (4.40–91.00) | 0.019 |

| ALB, g/l | 72 | 28.71±5.32 | 28.30 (19.30–48.40) | 59 | 34.00±5.84 | 34.80 (22.40–45.90) | <0.0001 |

| ALT, U/l | 72 | 34.08±41.06 | 23.50 (8.00–323.00) | 59 | 35.63±47.78 | 27.00 (5.00–368.00) | 0.842 |

| AST, U/l | 72 | 52.64±43.96 | 39.50 (8.00–261.00) | 59 | 49.73±66.04 | 29.00 (12.00–427.00) | 0.773 |

| ALP, U/l | 72 | 104.65±80.86 | 92.00 (17.00–517.00) | 59 | 100.31±77.30 | 80.00 (20.00–518.00) | 0.756 |

| GGT, U/l | 72 | 86.90±128.87 | 43.00 (9.00–912.00) | 59 | 103.78±150.48 | 45.00 (10.00–755.00) | 0.49 |

| BUN, mmol/l | 71 | 10.75±9.63 | 8.00 (1.77–61.88) | 60 | 6.05±3.35 | 5.33 (1.63–21.70) | <0.0001 |

| CR, µmol/l | 71 | 110.74±132.21 | 64.00 (31.00–702.00) | 60 | 57.97±23.49 | 54.00 (27.40–164.00) | 0.002 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/l | 72 | 4.04±0.73 | 3.88 (2.46–6.44) | 58 | 4.07±0.46 | 4.07 (3.23–5.90) | 0.587 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/l | 72 | 136.82±5.08 | 137.80 (121.00–145.60) | 58 | 139.19±4.23 | 139.70 (125.50–146.40) | 0.004 |

| Serum calcium, mmol/l | 55 | 2.06±0.21 | 2.12 (1.40–2.66) | 30 | 2.11±0.25 | 2.17 (1.73–2.47) | 0.264 |

| BA, µmol/l | 50 | 62.20±61.63 | 44.00 (9.00–415.00) | 29 | 44.17±30.90 | 32.00 (9.00–107.00) | 0.12 |

| PT, sec | 72 | 17.97±7.45 | 16.30 (12.50–62.80) | 60 | 15.28±3.07 | 14.25 (11.70–31.60) | 0.006 |

| APTT, sec | 72 | 47.41±18.48 | 44.60 (28.70–180.00) | 60 | 41.64±6.78 | 40.20 (28.00–58.00) | 0.016 |

| INR | 72 | 1.53±0.97 | 1.31 (0.93–7.96) | 60 | 1.22±0.34 | 1.11 (0.84–3.06) | 0.014 |

| In-hospital mortality | 72 | 5 (6.94) | 60 | 0 (0.00) | 0.081 | ||

| Child-Pugh score | 72 | 9.07±1.49 | 9.00 (7.00–14.00) | 58 | 6.22±1.28 | 6.00 (5.00–10.00) | <0.0001 |

| MELD score | 71 | 10.27±8.81 | 8.74 (−5.22–42.04) | 59 | 4.03±5.34 | 3.59 (−4.83–23.23) | <0.0001 |

| Ascites volume, ml (according to five-point method) | 71 | 2,272.00±1,586.40 | 2,009.00 (436.00–7,070.00) | ||||

ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BA, blood ammonia; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CR, creatinine; GGT, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase; Hb, hemoglobin; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; PLT, platelet; PT, prothrombin time; RBC, red blood cell; SD, standard deviation; TBIL, total bilirubin; WBC, white blood cell.

Clinical characteristics of patients with ascites >300 ml

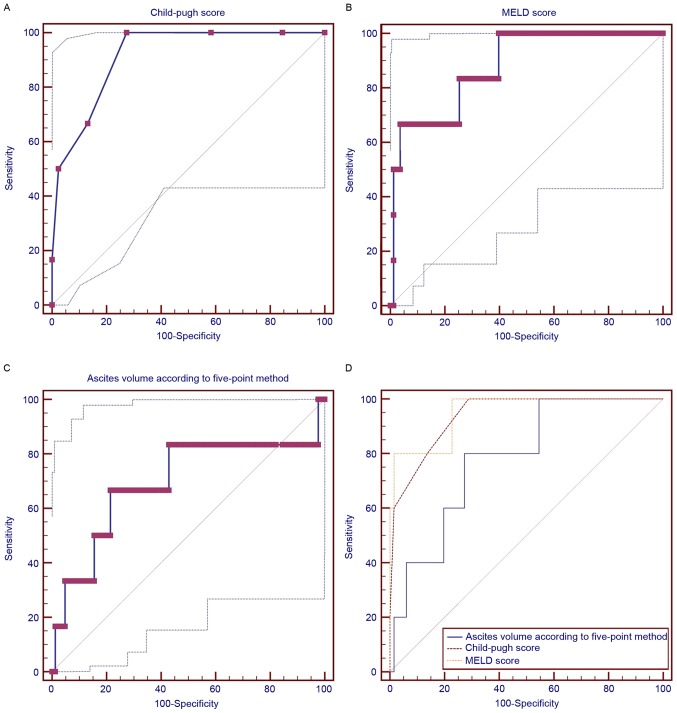

In patients with ascites >300 ml, the volume of ascites was positively and significantly correlated with serum potassium (r=0.248; P=0.036), BUN (r=0.359; P=0.002), in-hospital mortality (r=0.267; P=0.023), and blood ammonia (r=0.284; P=0.046) but negatively and significantly correlated with serum sodium (r=−0.336; P=0.004). The volume of ascites was not significantly associated with Child-Pugh score, MELD score, alanine aminotransferase, or aspartate aminotransferase (Table IV). The AUROCs of the Child-Pugh and MELD scores and ascites volume (>300 ml) for predicting the in-hospital mortality were 0.939 (95% CI, 0.856–0982), 0.952 (95% CI: 0.873–0.988), and 0.782 (95% CI, 0.668–0.871), respectively (Fig. 3). There were no significant differences among the variables (Child-Pugh vs. MELD, P=0.6281; Child-Pugh vs. volume of ascites, P=0.2063; MELD vs. volume of ascites, P=0.1874).

Table IV.

Correlation between different variables and ascites volume in patients with ascites >300 ml.

| Variables | N | Correlation coefficient, r | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male/female | 72 | −0.109 | 0.359 |

| Age, years | 72 | −0.014 | 0.908 |

| Causes of liver diseases, n (%) | |||

| Hepatitis B virus | 13 | 0.228 | 0.054 |

| Hepatitis C virus | 10 | −0.030 | 0.799 |

| Hepatitis B virus + hepatitis C virus | 3 | 0.098 | 0.413 |

| Alcohol | 18 | 0.081 | 0.497 |

| Hepatitis B virus + alcohol | 9 | −0.078 | 0.513 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 3 | −0.126 | 0.291 |

| Drug induced liver disease | 2 | −0.178 | 0.135 |

| PBC | 3 | −0.175 | 0.143 |

| Unknown | 10 | −0.062 | 0.608 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis + PBC | 1 | 0.039 | 0.748 |

| Laboratory tests | |||

| RBC, 1012/l | 71 | −0.106 | 0.381 |

| Hb, g/l | 71 | 0.001 | 0.993 |

| WBC, 1012/l | 71 | −0.026 | 0.830 |

| PLT, 109/l | 71 | −0.006 | 0.959 |

| TBIL, µmol/l | 72 | 0.018 | 0.883 |

| ALB, g/l | 72 | −0.078 | 0.512 |

| ALT, U/l | 72 | −0.067 | 0.576 |

| AST, U/l | 72 | 0.063 | 0.597 |

| ALP, U/l | 72 | −0.019 | 0.876 |

| GGT, U/l | 72 | 0.104 | 0.383 |

| BUN, mmol/l | 71 | 0.359 | 0.002 |

| CR, µmol/l | 71 | 0.232 | 0.052 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/l | 72 | 0.248 | 0.036 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/l | 72 | −0.336 | 0.004 |

| Serum calcium, mmol/l | 55 | 0.037 | 0.786 |

| BA, µmol/l | 50 | 0.284 | 0.046 |

| PT, sec | 72 | −0.040 | 0.737 |

| APTT, sec | 72 | −0.077 | 0.518 |

| INR | 72 | −0.050 | 0.675 |

| In-hospital mortality | 5 | 0.267 | 0.023 |

| Child-Pugh score | 72 | 0.102 | 0.394 |

| MELD score | 71 | 0.225 | 0.059 |

ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BA, blood ammonia; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CR, creatinine; GGT, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase; Hb, hemoglobin; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; PLT, platelet; PT, prothrombin time; RBC, red blood cell; SD, standard deviation; TBIL, total bilirubin; WBC, white blood cell. Not all patients had complete data therefore some tests assessed less individuals.

Figure 3.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curves of (A) Child-Pugh score, (B) MELD score and (C) the volume of ascites for predicting the in-hospital mortality of cirrhotic patients with ascites >300 ml. (D) Comparison of their diagnostic accuracy. MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

Discussion

Ascites is associated with a poor clinical outcome in liver cirrhosis (5). Indeed, the present study observed that all patients who did not survive presented with ascites, and cirrhotic patients with ascites had a higher rate of in-hospital mortality compared with those without ascites. However, the difference in in-hospital mortality rate between patients with and without ascites was not statistically significant.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to identify a significant association between the volume of ascites, assessed using the five-point method, and in-hospital mortality of cirrhotic patients. In patients with ascites >300 ml, in-hospital mortality was positively correlated with the volume of ascites. In addition, AUROC analysis indicated that ascites volume might be a modest predictor of in-hospital mortality rate in liver cirrhosis. Notably, the diagnostic accuracy of the volume of ascites was comparable to that of Child-Pugh and MELD scores. Both the Child-Pugh and MELD scores had no significant correlation with the volume of ascites. This result suggests that the volume of ascites may predict in-hospital mortality rate independently of Child-Pugh and MELD scores.

In a previous retrospective study by our group, the accuracy of Child-Pugh and MELD scores in predicting the in-hospital mortality of cirrhotic patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding was evaluated (15). The AUROCs of Child-Pugh and MELD scores were 0.796 and 0.810, respectively. By comparison, the present study observed that the AUROCs of Child-Pugh and MELD scores were higher in cirrhotic patients with ascites >300 ml (0.939 and 0.952, respectively). Thus, it may be concluded that the scores were more appropriate in the prognostic assessment of patients with ascites.

The present study also observed that serum sodium was significantly decreased and BUN was significantly increased in patients with ascites when compared with those without. Moreover, serum sodium was negatively correlated and BUN was positively correlated with the volume of ascites. The correlation between sodium and ascites is readily explained. Hyponatremia is a common complication in patients with ascites (16,17). Sodium retention causes the expansion of extracellular fluid volume and eventually results in the accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity (18). Furthermore, the occurrence of hyponatremia and increased BUN indicates renal function impairment, thereby resulting in ascites.

ALB, which is primarily synthesized by the liver, is an important compartment of plasma oncotic pressure (19). In previous studies, decreased levels of ALB suggested the presence of liver dysfunction, renal dysfunction and/or malnutrition (20,21). The present results indicated that patients with ascites had significantly lower ALB levels than those without ascites. When ALB levels are decreased, plasma oncotic pressure is reduced, thereby leading to the accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity (19).

The present study included a number of limitations. First, not all patients presenting with liver cirrhosis underwent abdomino-pelvic CT scans. Some patients underwent upper abdominal and/or mid-abdominal CT scans alone, and thus were excluded from the study. Second, the five-point method is designed to objectively measure the volume of ascites in patients with different types of cancer (9). Whether or not the method is appropriate in the evaluation of cirrhotic patients requires further confirmation. Third, only three fixed planes were selected for the five-point method. Thus, not all patients were subjected to the five-point method to assess the volume of ascites. Finally, it was difficult to accurately measure the thickness of ascites based on CT scans.

In conclusion, the present results indicated that the volume of ascites was positively correlated with the in-hospital mortality rate of cirrhotic patients. Thus, ascites volume should be considered in the prognostic assessment of cirrhotic patients with ascites.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AUROC

area under the receiver operating characteristic curves

- ALB

albumin

- APTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- CI

confidence intervals

- CT

computed tomography

- Hb

hemoglobin

- INR

international normalized ratio

- MELD

model for end-stage liver disease

- PT

prothrombin time

- RBC

red blood cell

- TBIL

total bilirubin

- 3D-CT

three-dimensional computed tomography

References

- 1.Philip G, Runyon BA. Treatment of patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:767–777. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1504367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gines P, Quintero E, Arroyo V, Terés J, Bruguera M, Rimola A, Caballería J, Rodés J, Rozman C. Compensated cirrhosis: Natural history and prognostic factors. Hepatology. 1987;7:122–128. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: A systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol. 2006;44:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ripoll C, Groszmann R, Garcia-Tsao G, Grace N, Burroughs A, Planas R, Escorsell A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Makuch R, Patch D, et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient predicts clinical decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:481–488. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Association for the Study of the Liver: EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2010;53:397–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore KP, Wong F, Gines P, Bernardi M, Ochs A, Salerno F, Angeli P, Porayko M, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. The management of ascites in cirrhosis: Report on the consensus conference of the International Ascites Club. Hepatology. 2003;38:258–266. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salerno F, Borroni G, Moser P, Badalamenti S, Cassarà L, Maggi A, Fusini M, Cesana B. Survival and prognostic factors of cirrhotic patients with ascites: A study of 134 outpatients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:514–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen JS, Bendtsen F, Møller S. Management of cirrhotic ascites. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6:124–137. doi: 10.1177/2040622315580069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oriuchi N, Nakajima T, Mochiki E, Takeyoshi I, Kanuma T, Endo K, Sakamoto J. A new, accurate and conventional five-point method for quantitative evaluation of ascites using plain computed tomography in cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:386–390. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imamoto H, Oba K, Sakamoto J, Iishi H, Narahara H, Yumiba T, Morimoto T, Nakamura M, Oriuchi N, Kakutani C, et al. Assessing clinical benefit response in the treatment of gastric malignant ascites with non-measurable lesions: A multicenter phase II trial of paclitaxel for malignant ascites secondary to advanced/recurrent gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:81–90. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishiguro T, Kumagai Y, Baba H, Tajima Y, Imaizumi H, Suzuki O, Kuwabara K, Matsuzawa T, Sobajima J, Fukuchi M, et al. Predicting the amount of intraperitoneal fluid accumulation by computed tomography and its clinical use in patients with perforated peptic ulcer. Int Surg. 2014;99:824–829. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00109.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646–649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, D'Amico G, Dickson ER, Kim WR. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464–470. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamath PS, Kim WR. Advanced Liver Disease Study Group: The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) Hepatology. 2007;45:797–805. doi: 10.1002/hep.21563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng Y, Qi X, Dai J, Li H, Guo X. Child-Pugh versus MELD score for predicting the in-hospital mortality of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:751–757. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barakat AA, Metwaly AA, Nasr FM, El-Ghannam M, El-Talkawy MD, Taleb HA. Impact of hyponatremia on frequency of complications in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Electron Physician. 2015;7:1349–1358. doi: 10.14661/1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim WR, Biggins SW, Kremers WK, Wiesner RH, Kamath PS, Benson JT, Edwards E, Therneau TM. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1018–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeda H, Kobayashi M, Sakamoto J. Evaluation and treatment of malignant ascites secondary to gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10936–10947. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i39.10936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF); Italian Society of Transfusion Medicine and Immunohaematology (SIMTI): AISF-SIMTI position paper: The appropriate use of albumin in patients with liver cirrhosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campillo B, Richardet JP, Scherman E, Bories PN. Evaluation of nutritional practice in hospitalized cirrhotic patients: Results of a prospective study. Nutrition. 2003;19:515–521. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(02)01071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Martinez R, Caraceni P, Bernardi M, Gines P, Arroyo V, Jalan R. Albumin: Pathophysiologic basis of its role in the treatment of cirrhosis and its complications. Hepatology. 2013;58:1836–1846. doi: 10.1002/hep.26338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]