Dear Editor

Germline mutations of the endomembrane-encoding gene TMEM127 confers susceptibility to neural crest-derived tumors pheochromocytomas (PHEOs)(Qin, et al. 2010) and have also been found in isolated renal cell carcinomas (RCCs)(Qin, et al. 2014). PHEOs and RCCs can arise as a result of inherited susceptibility, as in in von Hippel Lindau disease and in PHEO-paraganglioma syndromes related to mutations in succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) subunit genes(Dahia 2014; Maher 2011). The clinical spectrum and the signaling consequences of TMEM127 mutations remain poorly defined and it is not clear whether both tumors can be associated in families. This information would have an impact on surveillance and management of TMEM127 mutation carriers. Here we report the investigation of a TMEM127 mutation detected in a patient with both PHEO and RCC.

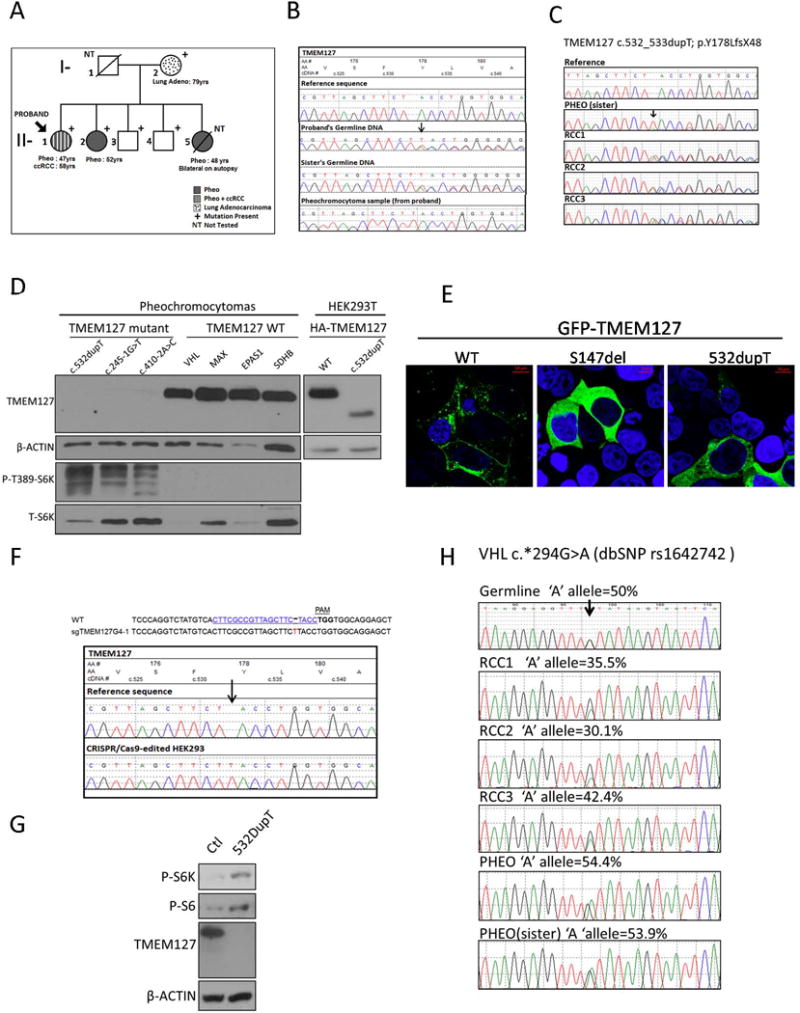

A female patient was diagnosed with a 3cm, right adrenal, metanephrine-secreting (PHEO) at age 47, and 11 years later, developed a Furhman grade I-II RCC with typical features of clear cell type. She remains disease-free after 18 and 7 years of follow up, respectively. She had two siblings with PHEOs, detected at 44 and 51 years of age, but no other RCCs. A germline truncating TMEM127 mutation, c.532_533dupT; p.Y178LfsX48, hereafter referred to as TMEM127-532dupT, was identified after a targeted, exome-based next generation sequencing screening (Fig.1C). No other pathogenic germline mutation was detected in other 35 pheochromocytoma and/or renal cancer susceptibility genes screened. Furthermore, no somatic mutations were found at high-depth sequencing (average 180x) of the proband’s frozen PHEO using Illumina TruSeq Cancer Panel screening of 42 cancer genes. The TMEM127-532dupT mutation was also detected in germline DNA from one affected sister (Fig.1A, 1B) and three other family members, their mother and two brothers, who have no evidence of PHEO or RCC (Fig. 1A). The proband’s mother was diagnosed with a lung adenocarcinoma at age 78. Analysis of the proband’s fresh-frozen PHEO DNA revealed loss of the wild-type TMEM127 allele (Fig.1B). These results support the germline TMEM127 mutation as the main driver event in this family (Qin et al. 2010). In contrast, no TMEM127 loss was found in three separate regions dissected from the proband’s formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) RCC (Fig.1C). Similar to the proband’s PHEO, the FFPE PHEO from the proband’s sister displayed clear loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the wild-type allele (Fig.1C), excluding potential artifacts due to fixed tissue quality. The lack of TMEM127 LOH in the RCC is in agreement with our earlier observation of retention of heterozygosity in a limited set of renal cancers with germline TMEM127 mutations(Qin et al. 2014). Interestingly, in this earlier report we noted decreased TMEM127 transcription in the tumors carrying these heterozygous variants, potentially suggesting a dosage effect of the TMEM127 mutation in renal tissue.

Figure 1.

A) Partial pedigree of a family with a germline TMEM127 mutation (c.532dupT, p.Y178LfsX48). Clinical features are indicated in the labels. Clinically unaffected mutation carriers are 87 (I-2), 62 (II-3) and 60 (II-4) years old. One additional, 54-year-old sibling (not shown) is negative for the mutation. B) Electropherograms of germline DNA from the proband (II-1) and one affected sister (II-2), and fresh-frozen PHEO from the proband, compared to the reference sequence. The single nucleotide insertion site is indicated with an arrow; the PHEO sample has no wild-type allele sequence. C) Electropherograms of archival, formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded tumor DNA: PHEO from affected sister and three separate subregions of the proband’s RCC, referred to as RCC-1, RCC-2 and RCC-3, compared to the reference sequence. Note loss of the wild-type allele in the PHEO but not in the RCC subregions. D) Western blot of lysates from the proband’s PHEO, two unrelated PHEOs carrying distinct TMEM127 mutations, and four PHEOS of other genetic backgrounds (mutated gene indicated), a separate gel of HEK293T cells expressing wild-type or c.532dupT TMEM127 construct containing an HA tag are shown to indicate the expected size of truncated c.532dupT TMEM127; Membranes were probed with TMEM127 (Bethyl Labs), phospho-Thr389- S6 kinase (S6K) and total S6K (Cell Signaling Technology), and β-actin (Sigma) as a loading control. E) Confocal microscopy images of HEK293T cells transiently transfected with GFP-tagged wild-type (WT) TMEM127 and GFP-TMEM127-532dupT mutant protein; a previously reported pathogenic mutant, GFP-TMEM127-S147del, was included as a positive control. WT-TMEM127 has a punctate pattern, S147del is diffusely distributed, and 532dupT is predominantly diffuse. F) GuideRNA (sgRNA) sequence used to genome-edit HEK293 cells, indicating the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence and the position of the nucleotide insertion of a clone. Corresponding electropherogram is shown below (arrow indicates inserted T at position c.532 on the TMEM127 sequence).G) Western blot of lysates from HEK293 control and 532dupT cells after amino acid starvation followed by exposure for 15 minutes. No TMEM127 protein is detected in the HEK293-TMEM127-532dupT cells. Phosphorylation of mTOR targets S6 kinase (S6K) and downstream S6 are shown and β-actin was used as a loading control. H) Electropherograms of germline and tumor samples spanning a VHL 3’UTR SNP (dbSNP rs1642742) used to estimate copy number at the VHL gene. DNA from proband’s germline and archival RCCs, as well as PHEO from proband and her sister PHEO. Percentage of the ‘A’ allele representation of each sample was estimated by the Mutation Surveyor program, as reported(Toledo, et al. 2016).

To further investigate whether the TMEM127-532dupT mutation was pathogenic, we explored its consequences in tumor tissue. No frozen material was available from the RCC and, in the absence of a reliable TMEM127 antibody for immunohistochemistry, no additional analysis of TMEM127 protein was available from this tumor. However, Western blot of protein lysates from the proband’s frozen PHEO using a polyclonal antibody that recognizes the TMEM127 N-terminus (Bethyl labs) (Qin et al. 2014) revealed neither full-length nor truncated TMEM127 bands (Fig 1D). Other TMEM127-mutant PHEOS included as controls also showed no TMEM127 expression, while TMEM127 protein was clearly detectable in PHEOs of other genetic origins but with intact TMEM127 sequence (Fig.1D), in support of instability of mutant TMEM127 protein. In addition, in agreement with our previous observations suggesting that the mTORC1 kinase pathway is activated after TMEM127 loss (Qin et al. 2010), phosphorylation of the mTORC1 downstream target S6 kinase (S6K) was increased in the TMEM127-532dupT PHEO and in the other TMEM127 mutant tumors, compared to TMEM127 wild-type PHEOs (Fig.1D).

Next, we examined TMEM127 subcellular distribution as another functional readout by expressing in HEK293T kidney cells a construct carrying this mutation fused with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) made by site directed mutagenesis, as described (Qin et al. 2010). The TMEM127-532dupT mutant showed a diffuse cytoplasmic pattern, similar to a previously reported pathogenic TMEM127 mutant (Qin et al. 2014), but distinct from the punctate endomembrane distribution of wild type TMEM127 (Fig.1E). We were unable to generate cells that retained stable expression of this mutant, further supporting its instability. To study the effects of the mutation in a more physiological context in renal cells, we generated HEK293 cells carrying homozygous TMEM127-532dupT mutation by CRISPR-Cas9-based genome modification using previously published protocols(Sanjana, et al. 2014) and a guide RNA that targeted the mutated nucleotide site or a control (Fig.1F). Stable clones carrying the c.532dupT mutation in homozygosity were obtained and verified by sequencing (Fig 1F). Similar to the proband’s PHEO, HEK293 TMEM127-532dupT cells had no detectable TMEM127 protein (Fig1G). Moreover, incubation of these cells with amino acids following 2 hours of amino acid deprivation, a powerful mTORC1 pathway activation input(Sancak, et al. 2010), led to higher mTOR target phosphorylation in HEK293 TMEM127-532dupT cells compared with control (Fig. 1G), suggesting that kidney cells with mutant TMEM127-532dupT have increased mTORC1 activation. Taken together, our data indicate that the TMEM127-532dupT mutation leads to loss of TMEM127 function both in primary PHEO and in renal cells, consistent with its pathogenic role.

In view of the lack of TMEM127 LOH in the RCC, we investigated other possible genetic causes. Immunohistochemistry for SDHB was positive, excluding an SDH mutation. We sequenced the coding region of the VHL gene in three subsections of proband’s RCC and found no mutations. We also evaluated VHL copy number using a SNP located in the 3’UTR of the gene (dbSNP rs1642742, c.*294G>A) that was heterozygous in the proband germline (Fig.1H). The three RCC regions showed variable imbalance of one allele (A; 36±6.1%), which was not detected in either of the PHEOs (~50%, Fig.1H). This finding is consistent with partial loss of one VHL allele in the RCC. VHL disruptions are the most frequent genetic event in sporadic kidney cancers and are usually biallelic (TCGA 2013). The partial VHL loss in our patient’s RCC suggests possible VHL involvement in this tumor, although we could not detect a second inactivating hit in the retained VHL allele. In addition, we cannot exclude that the partial VHL loss is a secondary, rather than an initiating, event in this tumor. Additional experiments (e.g. VHL promoter methylation) were limited by the lack of RCC tissue availability.

Taken together, our results establish the pathogenic nature of the TMEM127-532dupT mutation as the primary cause of PHEO, but do not conclusively link TMEM127 with the RCC in this family. However, it is not possible to completely exclude TMEM127’s contribution to the RCC. First, the late disease onset in this family could indicate that other mutation carriers may still develop the disease. Secondly, lack of LOH in previously reported RCCs with TMEM127 mutation (Qin et al. 2014) may point to different mechanisms of TMEM127 inactivation in the kidney or a haploinsufficiency effect. Finally, other cases of co-existence of PHEO and RCC were recently reported in the context of TMEM127 variants. One report described a patient with PHEO and clear cell RCC carrying a truncating germline TMEM127 mutation; however no information is available on the LOH status or somatic sequence profile of this tumor(Hernandez, et al. 2015). In a separate article, two patients presenting with paraganglioma associated with renal tumors, one with multiple papillary adenomas and another with clear cell RCC, had novel TMEM127 variants which target a conserved residue previously reported in a patient with PHEO(Gupta, et al. 2017). In summary, the rare co-occurrences of RCC and PHEO in TMEM127 mutant carriers may be simply coincidental and the RCC may be sporadic in these cases. However, the caveats discussed above and the increasing number of susceptibility genes common to both PHEOs and RCCs(Dahia 2014) justify augmented awareness and long-term follow up of TMEM127 mutation carriers in these families to conclusively establish whether their risk for RCCs is increased.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to members of the Familial Pheochromocytoma Consortium for their continuing collaboration, and patients and their families for their invaluable contributions. This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Individual Investigator Grants RP101202 and RP57154 (P.L.M.D), CPRIT Training Grant RP140105 (Y.D.); NRSA Institutional Predoctoral Training Grant T32CA148724 (S.K.F.); NIH-GM114102 (P.L.M.D.); Department of Defense CDMRP W81XWH-12-1-0508 (P.L.M.D.). The Optical Imaging Core Facility is supported by NIH-NCI P30-CA54174 (CTRC at UTHSCSA) and NIH-NIA P01-AG19316.

Footnotes

Contributions

P.L.M.D. supervised the entire study and research. Y.D., S.K.F and P.L.M.D. designed the research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. Y.D., S.K.F, Z-M.C., and Y.Q. performed all the laboratory experiments. R.S. and C.M. performed genetic counseling and clinical activities, respectively. All authors reviewed/edited the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- Dahia PL. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma pathogenesis: learning from genetic heterogeneity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:108–119. doi: 10.1038/nrc3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Zhang J, Milosevic D, Mills JR, Grebe SK, Smith SC, Erickson LA. Primary Renal Paragangliomas and Renal Neoplasia Associated with Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma: Analysis of von Hippel-Lindau (VHL), Succinate Dehydrogenase (SDHX) and Transmembrane Protein 127 (TMEM127) Endocr Pathol. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12022-017-9489-0. Epub 06/25/2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez KG, Ezzat S, Morel CF, Swallow C, Otremba M, Dickson BC, Asa SL, Mete O. Familial pheochromocytoma and renal cell carcinoma syndrome: TMEM127 as a novel candidate gene for the association. Virchows Arch. 2015;466:727–732. doi: 10.1007/s00428-015-1755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher ER. Genetics of familial renal cancers. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2011;118:e21–26. doi: 10.1159/000320892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Deng Y, Ricketts CJ, Srikantan S, Wang E, Maher ER, Dahia PL. The tumor susceptibility gene TMEM127 is mutated in renal cell carcinomas and modulates endolysosomal function. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:2428–2439. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Yao L, King EE, Buddavarapu K, Lenci RE, Chocron ES, Lechleiter JD, Sass M, Aronin N, Schiavi F, et al. Germline mutations in TMEM127 confer susceptibility to pheochromocytoma. Nat Genet. 2010;42:229–233. doi: 10.1038/ng.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Zhang F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Methods. 2014;11:783–784. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TCGA. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo RA, Qin Y, Cheng ZM, Gao Q, Iwata S, Silva GM, Prasad ML, Ocal IT, Rao S, Aronin N, et al. Recurrent Mutations of Chromatin-Remodeling Genes and Kinase Receptors in Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:2301–2310. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]