Abstract

O’Brien et al. (Research Articles, 24 February 2017, eaag1789) proposed a novel mechanism of primase function based on redox activity of the iron-sulfur cluster buried inside the C-terminal domain of the large primase subunit (p58C). Serious problems in the experimental design and data interpretation raise concerns about the validity of the conclusions.

Main Text

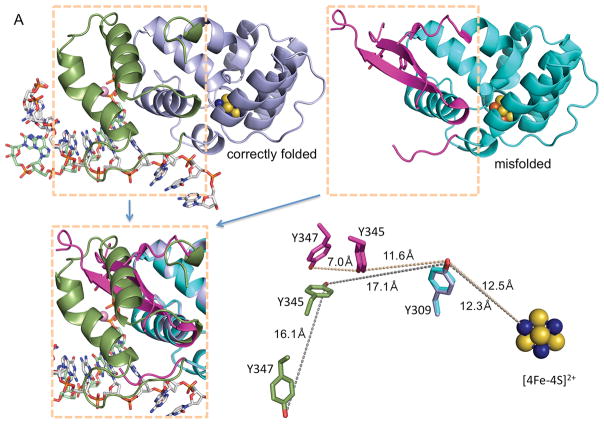

The human p58C protein used by O’Brien et al. (1) contains the I271S mutation and exhibits an anomalous structure at the DNA:RNA-binding interface that is drastically different from the conserved structure of human p58C and its yeast ortholog determined by two independent groups in four different protein assemblies (2–5) (Fig. 1A). Without any explanation or qualification, O’Brien et al. assumed that the β-hairpin structure in their mutated p58C binds the RNA:DNA substrate in the same way as the α-helical structure in wild-type (WT) p58C (see Figs. 3A, 3B, and S6 in (1)). Moreover, the authors concluded that Y345 and Y347, which are adjacent in the mutated p58C (Fig. 1A), participate in the charge transfer (CT) between the iron-sulfur cluster and the DNA substrate. But these two residues are 16.1 Å apart and oriented differently in the conserved p58C structure (Figs. 1A and 1B). Consequently, results of CT and DNA-binding experiments are not applicable to WT primase.

Fig. 1. Comparison of functionally relevant primase substrate and correctly folded p58C (4) with the substrate and misfolded p58C used by O’Brien et al. (1).

(A) Side-by-side comparison of p58C structures with correctly folded (PDB code 5F0Q) and misfolded (PDB code 3L9Q) substrate-binding regions highlighted in different colors. These regions are overlapped in the left bottom quarter. The positions of Y309, Y345 and Y347 relative to [4Fe-4S]2+ in two structures are shown in the right bottom quarter. The reason for p58C misfolding might be explained by substitution of structurally important I271 by serine in erroneously named “wild-type” p58C (PDB code 3L9Q) or by asparagine in its mutants Y345F and Y347F (PDB codes 5I7M and 5DQO, respectively). (B) Crystal structure of p58C in complex with a duplex containing 5′-triphosphate RNA and 3′-overhang DNA (4). (C) Primase substrate (6) with the 5′-triphosphate of a primer and the 3′-overhang of a template that are required for p58C binding are shown in blue. (D) Substrate used by O’Brien et al. (1) for electrochemistry experiments. In (C) and (D) the red-colored 5′-overhangs do not participate in binding of correctly folded p58C. The figure was prepared using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (version 1.8, Schrödinger, LLC).

DNA substrates used by O’Brien et al. in the binding and CT experiments are biologically irrelevant. Both the 5′-triphosphate of a primer and the 3′-overhang of a template are critical for DNA:RNA binding by p58C and primase (4, 6) (Fig. 1C, highlighted in blue). However, the substrate used by O’Brien et al. lacks these key binding elements (Fig. 1D), which results in affinity for mutated p58C less than 1/150 that of the natural substrate for WT p58C (Kd=5.5 μM versus 33 nM; see Fig. S1 in (1) and Table 2 in (6), respectively). Previously Chazin’s group obtained a Kd of 0.3 μM (Table S2 in (7)) instead of 5.5 μM as reported in (1) using the same protein, substrate and experimental procedure (1). This almost 20-fold difference was not explained.

The only supporting evidence by O’Brien et al. for the redox switch involvement in primer synthesis is the rate reduction of de novo RNA synthesis by the Y345F mutant. However, the rate reduction can be explained by a completely different mechanism. In the conserved p58C/substrate complex structure Y345 interacts with the γ-phosphate of the initiating NTP (Fig. 1B) (4), which is rather sensitive to the binding environment (8,9). For example, mutation of Arg306 analog in yeast primase, which makes two contacts with initiating NTP (4), completely abrogates de novo RNA synthesis (9). In comparison, Y345F mutation eliminates only one hydrogen bond (Fig. 1B) and, therefore, impairs the initiation partially. Consequently, the effect of Y345F mutation on synthesis initiation cannot be used as the evidence for Y345 participation in CT. Of the three Tyr residues suggested by O’Brien et al. to participate in the CT, only Y309 does not contact the DNA:RNA substrate (Fig. 1B), but the authors did not provide primer synthesis data for the Y309F mutant.

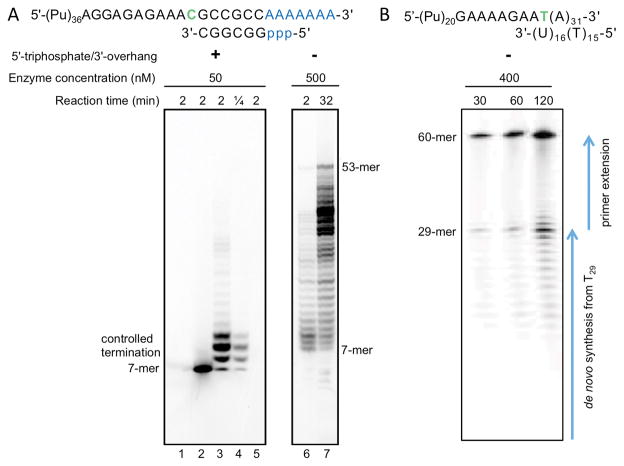

O’Brien et al. also claim that CT regulates primer truncation. However, they used a 31-mer primer that is longer than the functionally relevant 9-mer primer and lacks the elements that are essential both for reaction efficiency and for the control of synthesis termination (see Figs. 2A and 2B for comparison) (4, 10, 11). In their assay, primase generates a mixture of two product types: 32 to 60-mer products, synthesized during extension of a 31-mer primer, and RNA fragments with 5′-triphosphate and length of 2 to 31 nucleotides, that are originated from RNA synthesis initiation from T29 in the template. Obviously, the labels for 10-mer and 30-mer products are not consistent. Two important controls are missing: reaction in the absence of the primer to show only the products of de novo synthesis, and reaction in the absence of CTP/UTP allowing the visualization of the exact position of a 32-mer product on the gel. So the prominent band corresponding to an approximately 30-mer product (Figs. 5A and S14 (1)) is a result of de novo RNA synthesis termination due to reach of primer end (similar to termination in Fig. 4A (1)) rather than abrogation of extension of a 31-mer primer. Indeed, Fig. S14 confirms that Y345F substitution reduces the number of de novo synthesized primers, without any relation to CT. In the same manner, the absence of products with a length of approximately 30 nucleotides or less (as observed in Fig. 5A (right panel) (1)) relates to abrogation of de novo primer synthesis and not to disruption of CT, because the introduced mismatch definitely disturbs the short (6-bp) and AT-rich DNA:RNA duplex.

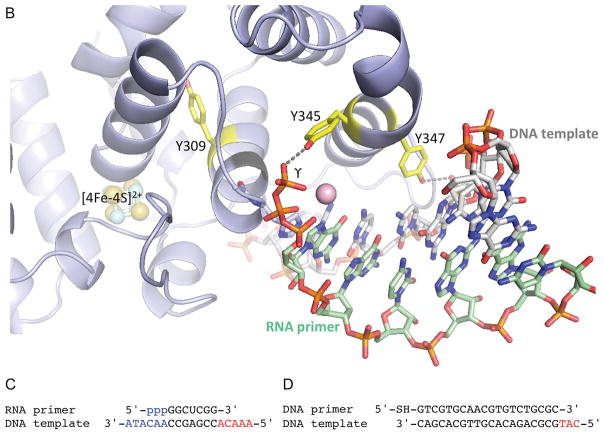

Fig. 2. Side-by-side comparison of experimental setups for examination of RNA synthesis termination by human primase.

(A) Example of primer elongation reactions showing the effect of template:primer structure on the efficiency of RNA synthesis termination by human primase as described by Baranovskiy et al. (6). When using the correct substrate containing 5′-triphosphate and 3′-overhang, there is pronounced termination of reaction mainly at 9-mer primers (lanes 3 and 4), which are optimal for extension by Polα (4). However, in the case of template:primer without 5′-triphosphate and 3′-overhang, primase loses the ability to terminate synthesis at 9-mer primers (lanes 6 and 7) and has dramatically reduced activity, which requires a higher load of the enzyme and longer reaction time. Primase activity reactions were reproduced as in (6). The products were labeled by incorporation of [α-33P]GTP at the seventh position of primer. Note that the negatively charged triphosphate moiety increases the mobility of RNA primers. Lanes 1 and 5, control incubations in absence of enzyme or primer, respectively. Lane 2, reaction was not supplied with CTP and UTP. (B) Example of incorrectly designed primer elongation reactions, which are not capable of capturing physiologically relevant primer termination. The image was adopted from Fig. 5A (1). Note high enzyme concentrations and long reaction time. The products with a length of 29 nucleotides or less are the result of RNA synthesis initiated from T29 in the template (primase initiates RNA synthesis only from a template pyrimidine in the presence of ATP or GTP (13)). Appearance of primers longer than 10 nucleotides is due to the absence of Polα or its catalytic core, which allows primase to rebind the 9-mer primer without involvement of p58C and extend further (6, 14). Unfortunately, the gel provided does not allow visualization of the products of de novo synthesis from 2-mer to 9 to 12-mer. Counting of bands below 29-mer product indicates that the lowest visible band corresponds to 18-mer primer, not to 10-mer as shown in Fig. S14 in (1).

No direct evidence was provided that the oxidized [4Fe-4S]3+ cluster was obtained during electrochemical experiments with p58C. Moreover, the affinity of DNA to p58C with the oxidized cluster was not measured to confirm the statement that this form binds more strongly to the template:primer. Actually, p58C without any electrochemical manipulations binds tightly to the correct substrate under aerobic conditions (6), in which the [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster of primase is stable (9, 12). The authors avoided comparison of primer synthesis in aerobic vs. anaerobic conditions but claimed the advantage of the latter. In fact, primase efficiently initiates and terminates RNA synthesis under aerobic conditions (6, 8), and the presence of an iron-sulfur cluster in Polα is still under debate (13). Moreover, Polα is absent in the primer elongation assay in (1), which renders the conclusion of its proposed role in termination of RNA primer synthesis a mere speculation.

Given the questionable results and the conclusions contradicting the biochemical, structural, and genetic data cumulated over three decades (13), we ask O’Brien et al to re-examine their experiments and reconsider the conclusions.

Acknowledgments

We thank William C. Copeland for scientific comments and Kelly Jordan for editing this manuscript. Preparation of Technical Comments was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant GM101167 to T.H.T.

References and Notes

- 1.O’Brien E, et al. The [4Fe4S] cluster of human DNA primase functions as a redox switch using DNA charge transport. Science. 2017;355 doi: 10.1126/science.aag1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarkar VB, Babayeva ND, Pavlov YI, Tahirov TH. Crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of human DNA primase large subunit: implications for the mechanism of the primase-polymerase alpha switch. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:926–931. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.6.15010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baranovskiy AG, et al. Crystal structure of the human primase. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:5635–5646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.624742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baranovskiy AG, et al. Mechanism of Concerted RNA-DNA Primer Synthesis by the Human Primosome. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:10006–10020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.717405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sauguet L, Klinge S, Perera RL, Maman JD, Pellegrini L. Shared active site architecture between the large subunit of eukaryotic primase and DNA photolyase. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baranovskiy AG, et al. Insight into the Human DNA Primase Interaction with Template-Primer. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:4793–4802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.704064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaithiyalingam S, Warren EM, Eichman BF, Chazin WJ. Insights into eukaryotic DNA priming from the structure and functional interactions of the 4Fe-4S cluster domain of human DNA primase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13684–13689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002009107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Copeland WC, Wang TS. Enzymatic characterization of the individual mammalian primase subunits reveals a biphasic mechanism for initiation of DNA replication. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26179–26189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klinge S, Hirst J, Maman JD, Krude T, Pellegrini L. An iron-sulfur domain of the eukaryotic primase is essential for RNA primer synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:875–877. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogawa T, Okazaki T. Discontinuous DNA replication. Ann Rev Biochem. 1980;19:421–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.002225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuchta RD, Reid B, Chang LM. DNA primase. Processivity and the primase to polymerase alpha activity switch. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16158–16165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiner BE, et al. An iron-sulfur cluster in the C-terminal domain of the p58 subunit of human DNA primase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33444–33451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baranovskiy AG, Tahirov TH. Elaborated Action of the Human Primosome. Genes (Basel) 2017;8 doi: 10.3390/genes8020062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Baranovskiy AG, Tahirov TH, Pavlov YI. The C-terminal domain of the DNA polymerase catalytic subunit regulates the primase and polymerase activities of the human DNA polymerase alpha-primase complex. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:22021–22034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.570333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]