Abstract

Most research designed to answer the “why” of the prescription opioid epidemic has relied on structured interviews, which rigidly attempt to capture the complex reasons people use opioids. In contrast this systematic literature review focuses on peer-reviewed studies that have used a qualitative approach to examine the development of an opioid-use disorder from the point of initial exposure. Rather than simply providing a “high,” opioids reportedly relieve psychological/emotional problems or provide an escape from life stressors. As use continues, avoidance of withdrawal sickness becomes an overriding concern, with all other benefits playing minor roles in persistent use. These studies indicate that terms used in structured interviews, such as “nontherapeutic use” or variations thereof, poorly capture the complex range of needs opioids satisfy. Both quantitative/structured studies and more qualitative ones, as well as more focused studies, have an important role in better informing prevention and treatment efforts.

Keywords: heroin use, prescription opioid abuse, progression of opioid use disorder, qualitative data, qualitative review

Abstract

La mayor parte de la investigación diseñada para responder al “por qué” de la prescripción epidémica de opioides se ha basado en entrevistas estructuradas, las cuales intentan rígidamente capturar las complejas razones que tienen las personas que utilizan opioides. En contraste, esta revisión sistemática de la literatura se enfoca en estudios de revisión de pares, los cuales han empleado una estrategia cualitativa para examinar el desarrollo de un trastorno por el uso de opioides desde el punto inicial de exposición. En lugar de proporcionar sólo un “vuelo”, al parecer los opioides alivian problemas psicológicos/emocionales o permiten escapar de los estresores vitales. A medida que su empleo continúa, la evitación del síndrome de abstinencia constituye una preocupación primordial, más allá de todos los otros beneficios que tienen menor importancia en el empleo persistente. Estos estudios señalan que los términos empleados en las entrevistas estructuradas, como “uso no terapéutico” o variaciones de esto, capturan pobremente la compleja gama de necesidades que satisfacen los opioides. Los estudios cuantitativos/estructurados y más aún los cualitativos, así como estudios más específicos, tienen un importante papel para contar con una mejor información en los esfuerzos de prevención y tratamiento.

Abstract

La plupart des recherches conçues pour répondre au « pourquoi » de l'épidémie de prescription d'opioïdes s'appuient sur des entretiens structurés qui tentent de façon rigoureuse de saisir les raisons complexes des utilisateurs d'opioïdes. À l'opposé, cette revue systématique de la littérature s'intéresse aux études évaluées collégialement dont l'approche qualitative permet l'analyse du développement d'un trouble de l'utilisation des opioïdes à partir de l'exposition initiale. Il semble que les opioïdes soulagent des problèmes psychologiques et/ ou émotionnels ou permettent de s'échapper du stress de la vie quotidienne plus qu'ils ne donnent une « défonce ». Tant que dure l'utilisation, éviter les syndromes de sevrage devient le souci primordial, le rôle joué par tous les autres bénéfices dans la persistance de l'utilisation étant mineur. D'après ces études, les termes employés ou leurs variantes, dans les entretiens structurés comme « utilisation non thérapeutique » sont insuffisants à décrire la variété complexe des besoins satisfaits par les opioïdes. Le rôle des études quantitatives structurées, des études qualitatives et des études plus ciblées est important pour mieux prévenir et mieux traiter.

Introduction

Prescription opioid abuse has increased dramatically in the past 20 years in the United States and, more recently, has spread to other countries as well (eg, Canada, several Asian countries).1-3 The United States is the world's largest consumer of opioids,4 and as prescriptions increased from 76 million in 1991 to 219 million in 2011,5 there were corresponding increases in opioid-related emergency room visits,6 treatment admissions,7 and overdose fatalities.8 An estimated 25 million people initiated nonmedical use of pain relievers between 2002 and 2011,9 and by 2014, 10.3 million Americans were reporting the nonmedical use of prescription opioids.10 What has motivated such a substantial increase in abuse? This is a difficult question to answer because most epidemiological studies to date (for systematic reviews see refs 4,11-13) have used standardized instruments, which do not allow a complete understanding of the multifaceted reasons users find prescription opioids so rewarding. For example, to be as inclusive as possible, many standardized questions ask a variation of, “have you used opioids in the past 30 days for nontherapeutic purposes?” If the answer is in the affirmative, we know that the individual has misused an opioid, but there is little context provided concerning why and for what nontherapeutic purpose prescription opioids were used.14 On the other hand, the value of qualitative data obtained by open-ended questions, once considered useful but then relegated to pseudoscience,15 is that those misusing or abusing opioids can describe in their own words why they found prescription opioids so rewarding that they continued to use them to the point that they developed a substance-abuse disorder. In this review, we discuss a recent resurgence—by a relatively small group of researchers—in recording qualitative data, which we believe have provided a much more solid foundation for understanding the demand for opioid analgesics and the progression from use to abuse than most quantitative epidemiological studies to date.

Selection of studies for review

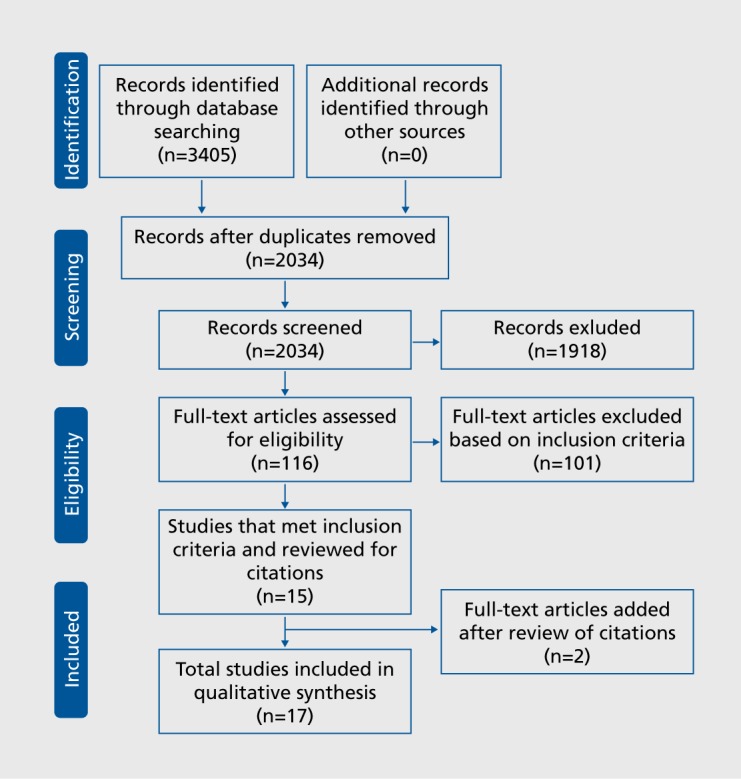

A systematic literature review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) format16 in August and September 2016 in order to identify peer-reviewed studies that used a qualitative approach for data collection, examining the progression from initial exposure to prescription opioids toward the development of an opioid-use disorder (see supplementary Figure 1 [online version] for schematic representation). PubMed and PsycINFO databases were searched using all iterations of the keyword sets “opioid,” “nonmedical, misuse, or abuse,” and “qualitative, interview, or focus group,” using the Boolean operator AND in between keywords (eg, opioid AND abuse AND qualitative). Inclusion criteria at this level included studies published in peer-reviewed journals in the previous 20 years, from 1996 to 2016. Citations were collated in EndNote, with 2034 studies identified after exclusion of duplicates from an original pool of 3405 studies.

These 2034 articles underwent a title/abstract evaluation in addition to screening for inclusion criteria that research was conducted on a population within the United States to control for cultural differences on the progression of prescription opioid abuse. After this initial screening, 116 full-text articles were pulled for further review. Inclusion criteria for this in-depth review were: (i) study sample included prescription opioid abusers, either at the time of study or at some point before the study period (ie, prescription opioid abusers who had transitioned to heroin); (ii) studies not only included qualitative research methods but presented qualitative data in the context of participant quotes and did not solely quantify qualitative data through coding schema; (iii) motifs relating to the onset and progression of prescription opioid abuse constituted a significant part of the study (ie, studies where onset was a very minor part that paved the way for the primary purpose of the study, such as buprenorphine treatment modalities, were excluded).

Fifteen articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis.17-31 Citations of these 15 articles were then reviewed, and on the basis of the inclusion criteria outlined above, two new articles were included that were not in the initial pool of 2034 studies,32-33 for a total of 17 articles (Figure 1). Table I provides the recruitment methods, data collection methods, populations, and major descriptive themes of each reviewed study.17-33

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

TABLE I. Qualitative studies on prescription opioid abuse.17-33 .

| First author, year | Study type | Population | Recruitment | Major descriptive themes |

| Back et al (2011) | Interviews, focus groups | 24 adults (12 male, 12 female) with prescription opioid dependance | Newspaper advertisements and flyers posted in local health clinics | Route of administration; motives for use; introduction to prescription opioids; time of use; other substance use |

| Daniulaityte et al (2006) | Interviews | 24 prescription opioid abusers (16 male, 8 female) | Outreach from substance abuse research centers | Initiation to prescription opioids; motives for abuse; patterns of misuse |

| Daniulaityte et al (2012) | Interviews | 47 prescription opioid misusers (25 male, 22 female) with no dependance | Respndent-driven sampling | Drug risks; addiction; overdose and death; organ damage; uncontrollable highs; naturalness and purity; route of administration; harms to the brain; legitimacy and acceptability of use; personal vulnerability and management of pain pill risks |

| Fibbi et al (2012) | Interviews | 34 prescription opioid misusers (25 male, 9 female) denied prescription opioids for the treatment of a pain condition | Natural settings (streets, parks, beaches, and college campuses) | Circumstances for receiving an opioid prescription; circumstances for not obtaining a prescription among ever denied; self-medication; transitions from prescription opioids to heroin |

| Harocopos and Allen (2015) | Focus groups | 19 prescription opioid misusers (14 male, 5 female) | Community health agencies | Initiation to prescription opioids |

| Harocopos and Allen (2016) | Interviews | 31 heroin users (25 male, 6 female) with histories of prescription opioid misuse | Community health agencies, chain referrals, venuebased street recruitment | Trajectories of misuse; dual-entity to single-entity pills; oral to intranasal administration; developing physical dependence; heroin use diffusion; heroin initiation |

| Inciardi et al (2009) | Focus groups | 32 prescription drug abusers (16 male, 16 female) | Substance abuse treatment programs | Sources of prescription drugs; popularity and prices of prescription drugs; prescription drugs as “gateway” drugs |

| Lankenau et al (2012) | Interviews | 50 injection drug users (35 male, 15 female) with history of prescription drug misuse | Targeted sampling, chain referrals | Initiation to prescription opioids; trajectories involving opioids, heroin and injection drug use |

| Mars et al (2014) | Interviews | 41 heroin injectors (21 male, 20 female) | Targeted sampling | Prescription opioid pill sources and distribution; contrasting cities and drug markets; progression from pills; chemical connections; supply-side changes |

| Merlo et al (2013) | Focus groups | 55 physicians (52 male, 3 female) with a history of prescription drug misuse | Physician Health Programs | Motives for prescription drug misuse |

| Momper et al (2011) | Focus groups | 49 American Indian adults and youth (19 male, 30 female); subset of oxycodone users (N=6) | Midwestern Indian Reservation | Oxycodone: levels of use; sources; motives for use; problems and consequences of use; intervention options; worries about barriers to recovery |

| Moore et al (2013) | Interviews | 22 adolescents and young adults (14 male, 8 female) with opioid dependance | Existing Randomized Clinical Trial | Consequences of opioid use; life telescopes; ambivalence/decisional balancing; loss of control and moments of clarity; behavioral therapy and buprenorphine |

| Mui et al (2013) | Interviews | 120 young adults prescription drug misusers (60 male, 60 female) | Key informants, chain referrals | Exposureto prescription drugs; motives for use; access to prescription drugs; setting of use |

| Rigg and Ibanez (2010) | Interviews | 45 prescription drug abusers (26 male, 19 female) | Print media, chain referral, treatment program | Motives for prescription drug abuse |

| Rigg and Murphy (2013) | Interviews | 90 treatment-seeking prescription opioid abusers (52 male, 38 female) | Substance abuse, treatment programs | Family history; motives for use; intiation to prescription drugs |

| St Marie (2014) | Interviews | 34 opioid abusers (20 male, 14 female) with chronic pain | Substance abuse, treatment programs | Chronic pain and addiction |

| Stumbo et al (2017) | Interviews | 121 adults (55 male, 66 female) with prescription opioid dependance | Addiction Medicine department chiefs | Pathwaysto opioid use disorder; treatment-related barriers; stigma of addiction |

Results

The rise of the prescription opioid epidemic

For many centuries, people have used opium or its components—morphine and other similar narcotics—to get “high” or feel mellow.34-35 For just about as long, opium and its derivatives have also enjoyed enormous popularity for their potent pain-relieving (analgesic) effects. Unfortunately, despite a century of efforts, no clever medicinal chemist has ever been successful in developing an opioid that is an effective analgesic that lacks the abuse potential of its parent compound. Thus, analgesia has, and still does, go hand in hand with addiction.

Given that analgesics have been around for hundreds of years, it is surprising that abuse of medical opioids, while always extant, was usually at relatively low levels (probably because of lack of access or availability). However, late in the last century, a huge momentum shift occurred in the United States in the use and abuse of opioid analgesics. This epidemic appears to be related to two major developments discussed in the ensuing sections of this review.

Pain as the “fifth vital sign”

First, fueled in large part by a massive “educational” campaign by a pharmaceutical company marketing a new, enormously popular extended-release analgesic (see below), there was an intense focus on the treatment of pain in medical circles.36 For example, in 1995, the president of a major scientific organization indicated that pain should be considered the “fifth vital sign.”37 This was codified by a nationally recognized and important nonprofit health-standards-setting and accrediting body, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO),38 which released a scathing report on the undertreatment of pain in the United States. It concluded that effective narcotic analgesics were available but seldom used, and that doctors were ignoring pain management because of an irrational fear of addiction. They argued that narcotics should be more widely used, (incorrectly) assuming that appropriate clinical use rarely generated addictive behaviors. Note, the scientific basis for this conclusion was founded on two brief reports (one, a letter) with serious flaws, reporting that abuse was rare in pain patients.39-40 This conclusion is not shared by most clinical scientists today. Although the extent of so-called iatrogenic dependence is currently unknown, it is certainly not negligible; there are estimates of up to 40% of all patients becoming “addicted” to opioids, with the caveat that in many studies, physical dependence was incorrectly equated to addiction.41 Nonetheless, this report made headlines nationwide; Time magazine featured it on its cover, characterizing it as a national scandal given that physicians were seemingly unaware about appropriate pain management, particularly the role of opioid analgesics.

This report and the subsequent campaign was successful to the point that doctors began prescribing narcotics in record numbers, some probably inappropriately.42 Inevitably, with this surge in the use of prescription drugs, new ones were avidly introduced by pharmaceutical companies eager to meet the new demand, and some diversion occurred by people who sought not pain relief but a “high.” Note, some diversion has probably always occurred, but when the number of prescriptions was low, the actual level of abuse was low. As the numbers of prescriptions grew, so did the actual amount diverted, if one assumes a fixed diversion rate. Several quotes demonstrate the link between prescribed opioids and diversion:

[W]hen you're going to [college]... you get to go to the health center for free and see doctors and what not... And one girl went in and got a bottle of [hydrocodone/acetaminophen] for having a sore throat and we were just like well—what the hell? And then more and more people started going in and everyone was getting like liquid codeine and [hydrocodone/acetaminophen] just like [snaps] easy.33

My friend that got into a couple of car accidents, she like, she got [prescription drugs] and like abused them so much and she kept going back to the doctor to get more and more ... she was like, “Holy crap this is coolest feeling! You have to try it!” So then I did.33

Nine studies included qualitative data on initiation into prescription opioid abuse,17-18,21,23,25,29-31,33 and all nine described a legitimate prescription leading to addiction as a primary pathway to prescription opioid abuse. To wit:

In the beginning, it killed the pain and it didn't bother me. I didn't have cravings for it or anything like that. When I couldn't stand the pain, I would take a pill. And then one day, I woke up and took a pill; there was no pain though... . It sneaks up on you, it grabs you without notice... I didn't know I was becoming addicted when I became addicted.17

When you first start taking em, you can take a couple pills and you feel nice. And then your body starts increasing its tolerance and you have to take more. And then, “Oh no! I'm two weeks into it and I don't have my prescription anymore, so let's go to a different doctor.” Before you know it, I'm going to so many doctors I can't keep track.29

I never was one that experimented or did drugs, or even really drank a lot... but four years ago, I had gastro-bypass surgery, and that's when I got hooked on [hydrocodone/acetaminophen]. They gave me the liquid [version]. I liked it. And it kind of went from there.31

The introduction of extended-release opioid analgesics

The second major factor responsible for the growth in prescription opioid abuse was the introduction of a sustained-release drug, oxycodone, that would provide pain relief for 8 to 12 hours.43 Oxycodone is an opioid agonist with very high affinity for the μ-opioid receptor, making it an excellent pain reliever but also a powerful euphorigenic agent. The drug, marketed as OxyContin, was attractive because it needed to be taken only once or twice a day, instead of every 2 to 4 hours.

The extended-release capsules contained a built-in delivery device that would release the drug slowly over time from a large self-contained reservoir of the active drug moiety. Given its slow-release properties, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), using skinnerian logic, concluded that the delay in reinforcement imposed by a slow release of oxycodone would dissuade abuse because to reinforce a behavior (eg, drug seeking), an immediate reward is necessary. Thus, the FDA allowed the sponsoring company to state in the package insert or label that abuse was expected to be low because of the slow release properties of the formulation.36 However, addicts cleverly and quickly realized that they could defeat the slow-release device by crushing or dissolving the pills, making large amounts of oxycodone immediately available in a form suitable for snorting or intravenous injection.44-45

Why was the introduction of oxycodone such an important milestone in the epidemic of prescription opioid abuse? There were two major reasons: first, as compared with a standard immediate-release tablet that typically contains 5 mg of active drug, the extended-release version could easily contain 80 mg or 14 times as much, making one pill go a very long way if the reservoir was breached through uncomplicated methods; and, second, of equal importance, the tablet contained large amounts of pure oxycodone, quite unlike most immediate-release compounds that are “adulterated” with acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), which most addicts are hesitant to use because of health considerations (eg, stomach bleeds or liver damage) and/or the irritation to the nasal passage and pain at the injection site in those for whom these routes of administration were desirable. Thus, oxycodone, while enjoying enormous popularity as an analgesic, also became a highly prized drug for abuse.36,46 As evidence, 70.6% (n=12/17) of the studies reviewed included participant quotations that directly mentioned abuse of oxycodone.17-19,21-24,26,28-30,33

Motivations for continued use of opioids

Prescription opioids as a safe alternative to illicit drugs

Aside from whatever rewarding sensations that led to repetitive use, several factors favored the use of prescription opioids in a new cadre of drug users. For most, they produced a good, dependable, “safe” high because unlike heroin, the dose is known with certainty and the pill was labeled clearly. Hence, the danger in overdose was thought to be greatly reduced.19 Moreover, they are legal, which translated (not always) to fewer legal problems for possession with intent to abuse or distribute. This “safety net” provided by opioid analgesics is emphasized by the following perspectives sampled from the eight studies (47.1%) that indicated safety as a contributing factor to prescription opioid abuse.17-19,22,24,29,32-33

All the pain pills, and things like that... I mean they're from your doctor, and so, I mean, they help people, so I don't really feel like they're that harmful... .[second participant] I mean... a doctor prescribes them to you... can't be that bad... 19

I sort of knew it was wrong, but at the same time I didn't think it was such a bad thing. My head was telling me, “Dude, the doctor prescribed this to you. How bad can it be?” I thought me catching a little buzz was harmless.29

I thought it was a safer drug because it was legal. So who cares if I'm abusing it, it's legal, so what are they going to do?22

Moreover, often to justify their use of pills and assuage any guilt, patients convinced themselves that heroin addicts were junkies, but pill addicts were more socially acceptable. To wit:

I actually frowned upon [heroin]. Like, for me that was the epitome of—I just had visions of the movies and somebody that's dirty and sitting in an alley. For me, that was heroin, like that was the bottom of the barrel. And, I knew in my head that it's basically the same thing as a blue. It's just pharmaceutical.21

Yeah, I'm not doing heroin. I'm not a heroin addict. I'm just a pill head. I have seen that a lot, especially with girls too.32

When you're on the street, the person that's doing heroin is a “junkie.” If you look at a person that's doing [oxycodone/acetaminophen] they would just say, “Well I just do [oxycodone/acetaminophen].” You know what I mean? For a long time when I did [oxycodone/acetaminophen] and didn't do dope, I looked at people as if they were junkies, but I wasn't.22

“Getting high” understates the reward value of opioid analgesics

Although “getting high” or altering mood with the relatively safe opioid analgesics was certainly the initial reaction that led many to further use, a good deal of research indicates that factors other than the obligatory “getting high” often motivates opioid use or, in fact, becomes more important in driving persistent use. Of 11 articles that noted motivations for continued use (64.7%),17-18,20,25-31,33 although self-medicating physical pain (n=6)17-18,20,25,30-31 and use for altering mood/pleasurable feeling (n=5)17-18,25,28,33 were noted, the most cited reasons included use as a response to life stressors (n=8)17-18,25-26,28-31 or as a means of self-medicating psychological issues, effects of trauma, or emotional pain (n=8).18,25-30,33 Table II 17,18,21,25-28,30-32,47 provides a sample of how influential individual life events (Table IIA) and history of psychological or emotional issues (Table IIB) are in the development of prescription opioid abuse. Other motivations noted include normalization (n=2),27-33 increased energy (n=1),17 boredom (n=1),26 enhanced sexual intimacy (n=l),17 and self-blame/addictive personality (n=1).18

TABLE II. Motivations for continued use of prescription opioids.17,18,21,25-28,30-32,47 .

| A. Cope with life stressors | B. Self-medicate psychological/emotional issues | C. Opioid maintenance |

| I started taking them [codeine tablets] 'cause I'm working hard, long hours, and I'm having leg pains and a back pain, and I'm having cramps real bad. So I started taking the codeine.18 | I realized that when I would go out and hang out with my friends, I wouldn't be afraid to approach girls... I would feel a lot more confident. And I ended up hooking up with girls that sober I wouldn't even approach because I'm a shy kid... There's just something about that confidence... ! sincerely believed that I did things better on opiates.32 | It took me two years to go from a quarter to a whole one but it took me a couple months to go from one to five, six, seven, eight a day... If you're taking that much for that long, you're not even taking it to get high. You don't get high anymore... You just get okay. You can function. And if you don't take, you get really sick, really sick. It was funny, because everybody always thinks they're not going to withdraw. Nobody thinks they're going to withdraw. “Nah, I'll be fine.”21 |

| I had a couple of root canals and I was prescribed some Hydrocodone for pain relief. I remembered it was one of the most wonderful feelings I had ever experienced. But it really did not take hold at that time. Later, when my life was unraveling in other areas, medical mal-practice suit, and financial problems, I remembered how good that made me feel. And I needed help. I was going to help myself by taking this medication. 25 | I was raped five years ago, and I went through a very bad depression and everything. And I wanted to get messed up. I went to a friend's house. They're like, “oh, these new pills are out, ” and they were just a little blue pill. So cute. You know? It was tiny and blue. It was just to numb myself and what I was going through from being raped.28 | The doctor started giving me pills, and you know, my leg, I was still in pain. It was like a double-edged sword, you know, and then from there I started using heroin, to help me with my pain. And that really helped in the beginning. I would feel no pain for the whole day sometimes. I wound up getting hooked and it took me from living in a house to living on the street. It just destroyed my life. I didn't intend on becoming a junkie, I didn't intend on catching the habit-nothing like that. I just wanted to get the pain over with, but it was so excruciating. That's what happened like a downward spiral, everything from there just went down.30 |

| When I came home there was a huge argument and... from my head to my toes I wanted nothing more than to get high, and I knew that once I got high I would be able to deal with the situation in a better way.17 | After my son died [unexpectedly], I hit the [hydrocodone/acetaminophen] pretty hard... the prescription was for four a day... for pain. And I was taking quite a bit more than that. You know, I was self-medicating... it just kind of numbed me to what was going on around me. I was able to kind of deal with my wife and her problems, and everything else.31 | If I didn't have it in my system, I was throwing up, I was extremely sick... If I didn't have the [oxycodone hydrochloride] or the [oxycodone] or the methadone, I was dope sick... I thought I was going to have a heart attack. Your heart races, you're shaking... as long as I had it in my system I was okay.28 |

| There ain't nothing to do. And I think that's why we, a lot of us do them because we're so unhappy in our relationships and with our lives.26 | They made me feel better-it took the pain away, 'cause I lost my mom, and my father, and my sister in the same year, and I was hurting at the time... 18 | [Withdrawal] is like experiencing what it might be like to be insane... I totally hated it, and I wanted to use drugs so I wouldn't feel it.27 |

| For escape and relief for myself. I don't know why I get very depressed a lot of times. Escape is always a part of it for me. You know? I have a lot of problems out there. I have a lot of issues out there. I'm always looking over my shoulder. I have people calling my mother's house saying they're going to cut my throat. I have, you know a fiancée that's pregnant who her health problems far exceed mine. So that's nerve-wracking. Just through this drug use—the amount of people I've lost. I have had a girlfriend die in my arms—things like that. I want to escape those feelings.28 | Drugs treated a rather overwhelming anxiety and not being comfortable in my own skin, being shy, being uncomfortable around other people, being worried all the time about things, just an angst and malaise that, fortunately, I no longer have.25 | So we started doing them [oxycodone hydrochloride], and we, like, got so high. It was, like, the best high, and so we kept going back and getting more and more. I just wanted them 'cause I liked the high from them, but then it became about maintaining.28 |

| It helps mentally... your mind's thinking of other things and you don't' have time to sit and maybe dwell on things you shouldn't be... it helps.17 | It just kills everything. It even numbs your mind—to um sad things or emotional things.26 | So I wouldn't have withdrawals. I hated taking them so much to that point that I started to cry every time I took a hit.47 |

From these qualitative data, it seems clear that opioids provide a variety of “benefits” to those who would misuse them well beyond just getting high. The utility of these drugs in relieving anxiety and depression implies that there is probably considerable psychopathology in those who are diagnosed with a substance abuse disorder. This supposition is supported by a great deal of research that has found high rates of psychiatric comorbidity in those who abuse opioids.48-51 Thus, in many respects, it seems clear that self-medication of an underlying disorder52 becomes a driving force in the persistent use of opioids. It is difficult to overstate the strength of the reinforcing effects of opioids in motivating drug-seeking behavior. Once opioids take hold, many users are willing to go to almost any extremes to get them. As one young male stated:

Beginning of my senior year... I found [my mother's] prescription of extra strength [hydrocodone/acetominophen], in her purse. And I took four of them after a football game... I was on top of the world... from there on I just got really deep into them until I was nineteen... all my money was going towards buying pills... [or] I would go and say I got in a car accident... If couldn't buy any [pills], I'd break my hand and go sit in the ER... And then I got introduced to heroin. And it was cheaper and easier to get.31

The cycle of dependence

As abuse progresses from initial exposure from experimentation to get high or as a result of the added “benefit” of an opioid prescribed for pain, the development of physical dependence, manifested by a withdrawal syndrome rises in importance for persistent opioid abuse and indeed becomes a driving force to the exclusion of getting high or relief from life's difficult circumstances. Table IIC provides a sample of quotes from eight studies reviewed (47.1%) that described the strong motivating influence of withdrawal.18,21,24-26,28,31-32

I was addicted to them by then. You don't, get high after a while. You just need it so you're not sick. You have to have that balance... . I think I thought I was getting high, but after a while it's just not—it's just, to take away the symptoms and feel normal.28

What is clear here is that most chronic abusers who meet criteria for a substance (opioid) use disorder, according to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5), rather quickly lose the sensation that was so powerful in inducing the potent craving for opioids. Instead, attempting to escape from life-altering drug-seeking behavior is made more difficult—nearly impossible—by the generation of potent withdrawal symptoms, which drives further use.

Transitions to heroin

Beginning in 2010, prescription narcotic abuse appeared to level off,53 probably as a result of several factors, including the implementation of prescription monitoring programs, federal and local efforts to close “pill-mills” and eliminate script doctors, and the advent of abuse-deterrent formulations of extended-release opioids. As the supply of opioid analgesics decreased and the price rose, addicts faced two stark choices: stop using opioids altogether, or shift to something more accessible and affordable. For many, as the drug of choice became less accessible or more expensive (an excellent example of the economic law of supply and demand), heroin—once heavily stigmatized—became a practical necessity:

I was big into [oxycodone] at first... It wasn't until the [oxycodone] switched from OC to OP, and the non-tamper-proof versions [sic], that I really just went straight to heroin and immediately started shooting it, which I guess was a little over a year ago.24

When I first started doing drugs I started taking the pills, like [alprazolam, oxycodone, oxycodone/acetaminophen], anything that was prescription. After that I progressed into heroin and cocaine because... sometimes the prescription drugs are real expensive. Most pills like an [oxycodone] can be $40. So it was just getting too expensive for me.22

Heroin as an alternative to preferred opioid analgesics

Based on the preceding discussion, it is clear that heroin use has grown in response to efforts to control the supply of prescription opioid analgesics. Moreover, or as a result, heroin became a cheap and more accessible alternative to prescription opioids. But, perhaps as or more important, the social stigma associated with heroin use also began to dissipate, leading to its more widespread acceptance, even in those for whom its use was simply to get high (ie, whether or not related to the short supply of expensive opioids).

I'm sure that like cracking down on the doctors, the government didn't plan for this to happen, but it was just perfectly set up for street dealers because people are already addicted to powerful pharmaceutical grade opiates, and heroin in itself, though it's not pharmaceutical or made in a laboratory, is a powerful opiate. So you have a bunch of middle-class white kids with money, with families that come from money, that already have a predisposition to the physical addiction of opiates, so of course, heroin is going to explode, you know.21

I went to pick up [oxycodone] from one of my connects and he was like, “Oh, I'm out of [oxycodone] but I have black tar.”

And at the time I was smoking [oxycodone]. And so I was just like I didn't want to inject at that time in my life so I was just like, “I don't want to shoot anything up.” And he was just like, “No, you can smoke them the same way. Just put it on foil and smoke it the same way.” And I was like, “Oh.”24

I knew it [heroin] was really bad... . But like I said, it was a disconnect at first—that heroin was completely separate than pain medication. I didn't know that there was a one-to-one analogy at first... . And then my friends were like, “What the fuck are you doing? You take this shit all the time.“ And that's when they explained to me that opiates, opium, heroin, same thing.21

It is apparent from the data described above that users in this new and emerging heroin epidemic are different in many ways from those who used heroin 20 to 30 years ago: minority impoverished men living in inner city environs in 1960-1970 compared with today's new breed of heroin addicts—white males and females living in suburban and rural areas.54

What accounts for the dramatic shift in demographics is really not that complex. Since most heroin users today began their opioid use with prescription drugs as a safer alternative to heroin, it seems obvious that as access to these drugs became more difficult, the transition to heroin occurred in a population of “pill users”—white, middle class males and females with regular access to medical care and who generally carried adequate insurance to cover the cost.

Conclusion

The lesson to be learned from the foregoing discussion of the interchange between prescription opioids and heroin abuse is the first principle learned in Economics 101. Thus, as demand rises, the supply will be increased, usually at higher cost, to meet the demand. This axiom is no less true for the drug trade than it is for any other industry. Consequently, if there is a demand for opioids, that need will be met by entrepreneurs moving in to fill the void and enhance their revenue. As a corollary to this, if one simply focuses on supply—such as Prescription Monitoring Programs (PMPs), legislative crack-down on “pill mills” and “script doctors,” and abuse deterrent formulations—and does not address the “why” or the demand, we are unlikely to make many inroads into the opioid-abuse problem. A good place to start is a massive educational campaign aimed at prevention by stressing the obvious horrors associated with opioid abuse, including overdoses and, equally important, the negative impact on a healthy and productive life. Some argue this probably would be unsuccessful, but to these doubters, one simply has to look at what has happened to cigarette use in the United States over the past 25 years. Educational efforts do work and the case for cessation of opioid use is at least as compelling as that for cigarette smoking. Additionally, the development of more effective treatment programs that have much smaller rates of recidivism than our current programs would go a long way toward stopping abuse once it has progressed to the point where treatment becomes appropriate.

As pointed out in the introduction, there are many reviews of survey-driven research directed at understanding the growth in the use of opioids for their mood-altering effects.4,11-13 Although the studies covered in those reviews use well-validated, structured interviews that provide uniformity and reproducibility in results of considerable value, they lack the potential to open new avenues of research and often raise more questions than they answer. For example, assessments of risk for abuse among those prescribed opioids have had no consensus, and prevalence rates of dependence after treatment with prescription opioids range from 0% to 31 %.55 As we believe we have concluded appropriately, qualitative research—once dismissed as pseudoscience15—can go a long way to helping us understand what needs these abused substances fulfill and potential risk factors that can be identified at an individual level (eg, stressful life events, past trauma). Hopefully, these studies will better inform future research, prevention, and treatment efforts.

Global relevance

A very logical question that can be raised is whether a review of this literature focused on a problem that might be unique to the United States is relevant to the rest of the world. There are at least two responses. First, there is some evidence that abuse of prescription opioids is becoming a global issue, with Canada and Asia now reporting rising levels of prescription opioid abuse1-3; second, and far more important, stripping away the type of opioid used, the subjective effects of opioids, and the progression from use to abuse to treatment are essentially the same no matter what licit or illicit opioid is used. That said, in subsequent studies, it would be useful to examine any cultural factors that differentiate US users from people living in other developed or third-world countries in terms of their drug selection and motivations for excessive opioid use.

Acknowledgments

Theodore J. Cicero serves as a paid consultant on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Researched Abuse, Diversion and Addiction-Related Surveillance (RADARS) System, an independent nonprofit post-marketing surveillance system that is supported by subscription fees from pharmaceutical manufacturers. None of the authors have a direct financial, commercial, or other relationship with any of the subscribers of the RADARS System. Matthew S. Ellis has no financial disclosures.

Contributor Information

Theodore J. Cicero, Washington University Department of Psychiatry, St Louis, Missouri, USA.

Matthew S. Ellis, Washington University Department of Psychiatry, St Louis, Missouri, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dargan PI., Wood DM. Recreational drug use in the Asia Pacific region: improvement in our understanding of the problem through the UNODC programmes. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(3):295–299. doi: 10.1007/s13181-012-0240-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischer B., Gooch J., Goldman B., Kurdyak P., Rehm J. Non-medical prescription opioid use, prescription opioid-related harms and public health in Canada: an update 5 years later. Can J Public Health. 2014;105(2):e146–e149. doi: 10.17269/cjph.105.4143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert L., Primbetova S., Nikitin D., et al Redressing the epidemics of opioid overdose and HIV among people who inject drugs in Central Asia: the need for a syndemic approach. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(suppl 1):S56–S60. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Narcotics Control Board. Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2008. New York, YK: United Nations Publications; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Compton WM., Boyle M., Wargo E. Prescription opioid abuse: problems and responses. Prev Med. 2015;80:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) findings on drug-relate emergency department visits. In: The DAWN Report. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; February 22, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2002-2012. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. BHSIS Series S-71, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4850. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Number and age-adjusted rates of drug-poisoning deaths involving opioid analgesics and heroin: United States, 1999-2014. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_policy/AADR_drug .poisoning_involving_OA_Heroin_US_2000-2014.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. NSDUH series H-44, HHS publication No. (SMA) 12-4713. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maxwell JC. The prescription drug epidemic in the United States: a perfect storm. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30(3):264–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McHugh RK., Nielsen S., Weiss RD. Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkerson RG., Kim HK., Windsor TA., Mareiniss DP. The opioid epidemic in the United States. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2016;34(2):e1–e23. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zacny JP., Lichtor SA. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids: motive and ubiquity issues. J Pain. 2008;9(6):473–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan MJ. Qualitative research: science or pseudo-science? Psychol. 1998;11:481–483. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman DG. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Back SE., Lawson KM., Singleton LM., Brady KT. Characteristics and correlates of men and women with prescription opioid dependence. Addict Behav. 2011;36(8):829–834. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniulaityte R., Carlson RG., Kenne DR. Initiation to pharmaceutical opioids and patterns of misuse: preliminary qualitative findings obtained by the Ohio Substance Abuse Monitoring Network. J Drug Issues. 2006;36(4):787–808. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniulaityte R., Falck R., Carlson RG. “I'm not afraid of those ones just 'cause they've been prescribed”: perceptions of risk among illicit users of pharmaceutical opioids. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23(5):374–384. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fibbi M., Silva K., Johnson K., Langer D., Lankenau SE. Denial of prescription opioids among young adults with histories of opioid misuse. Pain Med. 2012;13(8):1040–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harocopos A., Allen B., Paone D. Circumstances and contexts of heroin initiation following non-medical opioid analgesic use in New York City. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;28:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inciardi JA., Surratt HL., Cicero TJ., Beard RA. Prescription opioid abuse and diversion in an urban community: the results of an ultrarapid assessment. Pain Med. 2009;10(3):537–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lankenau SE., Teti M., Silva K., Jackson Bloom J., Harocopos A., Treese M. Initiation into prescription opioid misuse amongst young injection drug users. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mars SG., Bourgois P., Karandinos G., Montero F., Ciccarone D. “Every 'never' I ever said came true”: transitions from opioid pills to heroin injecting. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(2):257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merlo LJ., Singhakant S., Cummings SM., Cottier LB. Reasons for misuse of prescription medication among physicians undergoing monitoring by a physician health program. J Addict Med. 2013;7(5):349–353. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31829da074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Momper SL., Delva J., Reed BG. OxyContin misuse on a reservation: qualitative reports by American Indians in talking circles. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(11):1372–1379. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.592430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore Sk., Guarino H., Marsch LA. “This is not who I want to be:” experiences of opioid-dependent youth before, and during, combined buprenorphine and behavioral treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49(3):303–314. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.832328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rigg KK., Ibanez GE. Motivations for non-medical prescription drug use: a mixed methods analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39(3):236–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rigg KK., Murphy JW. Understanding the etiology of prescription opioid abuse: implications for prevention and treatment. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(7):963–975. doi: 10.1177/1049732313488837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.St Marie B. Coexisting addiction and pain in people receiving methadone for addiction. West J Nurse Res. 2014;36(4):534–551. doi: 10.1177/0193945913495315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stumbo SP., Yarborough BJ., McCarty D., Weisner C., Green CA. Patient-reported pathways to opioid use disorders and pain-related barriers to treatment engagement. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;73:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harocopos A., Allen B. Routes into opioid analgesic misuse: emergent typologies of initiation. J Drug Issues. 2015;45(4):385–395. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mui HZ., Sales P., Murphy S. Everybody's doing it: initiation to prescription drug misuse. J Drug issues. 2013;44(3):263–253. doi: 10.1177/0022042613497935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Way EL. History of opiate use in the Orient and the United States. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;398:12–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb39469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright AD. The history of opium. Med Biol Illustration. 1968;18(1):62–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US GAO (General Accounting Office). OxyContin abuse and diversion and efforts to address the problem. GAO-04-110. Washington, DC. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d041 10. pdf. Published December 2003. Accessed June 14, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell JN. APS 1995 Presidential address. Pain Forum. 1996;5(1):85–88. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips DM. JCAHO pain management standards are unveiled. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. JAMA. 2000;284(4):428–429. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.423b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Portenoy RK., Foley KM. Chronic use of opioid analgesics in non-malignant pain: report of 38 cases. Pain. 1986;25(2):171–186. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Porter J., Jick H. Addiction rare in patients treated with narcotics. N Engl J Med. 1980;302(2):123. doi: 10.1056/nejm198001103020221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beauchamp GA., Winstanley EL., Ryan SA., Lyons MS. Moving beyond misuse and diversion: the urgent need to consider the role of iatrogenic addiction in the current opioid epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2023–2029. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benziger DP., Miotto J., Grandy RP., Thomas GB., Swanton RE., Fitzmartin RD. A pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic study of controlled-release oxycodone. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(2):75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carise D., Dugosh KL., McLellan AT., Camilleri A., Woody GE., Lynch KG. Prescription OxyContin abuse among patients entering addiction treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1750–1756. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.07050252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hays LR. A profile of OxyContin addiction. J Addict Dis. 2004;23(4):1–9. doi: 10.1300/J069v23n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katz N., Fernandez K., Chang A., Benoit C., Butler SF. Internet-based survey of nonmedical prescription opioid use in the United States. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(6):528–535. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318167a087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cicero TJ., Ellis MS. Understanding the demand side of the prescription opioid epidemic: does the initial source of opioids matter? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173(suppl 1):S4–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldner EM., Lusted A., Roerecke M., Rehm J., Fischer B. Prevalence of Axis-1 psychiatric (with focus on depression and anxiety) disorder and symptomatology among non-medical prescription opioid users in substance use treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses. Addict Behav. 2014;39(3):520–531. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manchikanti L., Giordano J., Boswell MV., Fellows B., Manchukonda R., Pampati V. Psychological factors as predictors of opioid abuse and illicit drug use in chronic pain patients. J. Opioid Manag. 2007;3(2):89–100. doi: 10.5055/jom.2007.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schieffer BM., Pham Q., Labus J., et al Pain medication beliefs and medication misuse in chronic pain. J Pain. 2005;6(9):620–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wasan AD., Butler SF., Budman SH., Benoit C., Fernandez K., Jamison RN. Psychiatric history and psychologic adjustment as risk factors for aberrant drug-related behavior among patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(4):307–315. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3180330dc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(11):1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dart RC., Surratt HL., Cicero TJ., et al Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Eng J Med. 2015;372:241–248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cicero TJ., Ellis MS., Surratt HL., Kurtz SP. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(7):821–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Minozzi S., Amato L., Davoli M. Development of dependence following treatment with opioid analgesics for pain relief: a systematic review. Addiction. 2013;108(4):1450–1457. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]