Abstract

Opioid maintenance treatment is the first-line approach in opioid dependence. Both the full opioid agonist methadone (MET) and the partial agonist buprenorphine (BUP) are licensed for the treatment of opioid dependence. BUP differs significantly from MET in its pharmacology, side effects, and safety issues. For example, the risk of respiratory depression is lower than with MET. The risk of diversion and injection of BUP have been reduced by also making it available as a tablet containing the opioid antagonist naloxone. This review summarizes the clinical effects of BUP and examines possible factors that can support decisions regarding the use of BUP or MET in opioid-dependent people.

Keywords: buprenorphine, methadone, opioid, opioid dependence, outcome, treatment

Abstract

La primera elección para el tratamiento de la dependencia a opioides es la terapia de mantenimiento con opioides. Tanto la metadona (MET), agonista opioide total, como la buprenorfina (BUP), un agonista parcial, están autorizados para el tratamiento de la dependencia a opioides. La BUP se diferencia significativamente de la MET en su farmacología, los efectos indeseables y la seguridad. Por ejemplo, el riesgo de depresión respiratoria es menor con BUP que con MET. El riesgo del uso recreativo y de la inyección de BUP se ha reducido al tenerla disponible también en forma de comprimidos que contienen el antagonista opioide naloxona. Esta revisión resume los efectos clínicos de la BUP y analiza posibles factores que puedan sustentar decisiones en relación con el uso de BUP o MET en personas dependientes de opioides.

Abstract

Le traitement d'entretien aux opioïdes est l'approche de première ligne dans la dépendance à ces substances. La méthadone (MET), agoniste complet des opioïdes, et la buprénorphine (BUP), agoniste partiel, sont autorisés tous les deux pour le traitement de la dépendance aux opioïdes. La pharmacologie, les effets secondaires et les problèmes de sécurité d'emploi de la BUP sont très différents de celle de la MET. Par exemple, le risque de dépression respiratoire est plus faible qu'avec la MET. Le risque de détournement et d'injection de la BUP a été réduit en la présentant aussi sous forme de comprimés contenant de la naloxone, un antagoniste des opioïdes. Cet article résume les effets cliniques de la BUP et s'intéresse aux facteurs susceptibles d'influer sur la décision d'utiliser la BUP ou la MET chez les personnes dépendantes aux opioïdes.

Introduction: extent of the problem

Opioid dependence results in clinically significant impairment. According to the tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) 1 and the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV),2 opioid dependence is a chronic medical disorder characterized by various somatic, psychological, and behavioral symptoms (three out of six or seven criteria must be fulfilled). Both of those classification systems follow a categorical approach. In contrast, the fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5) 3 takes a dimensional approach to substance-use disorders and lists 11 symptoms: a severe disorder is defined as the presence of at least six symptoms, a moderate disorder as the presence of 4 to 5, and a mild disorder as the presence of 2 to 3.

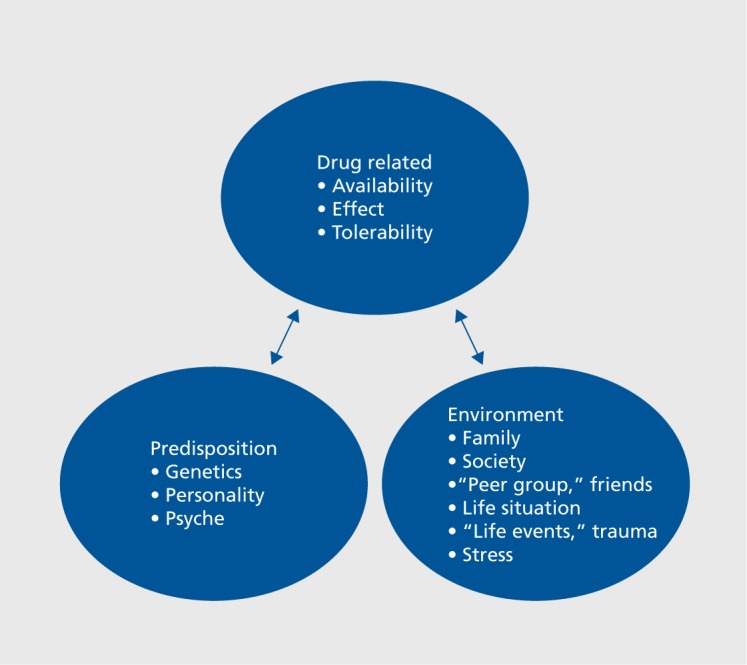

The risk of developing a substance-use disorder is related to several factors, such as the pharmacology of the drug, genetics, personality, family, and the individual microcosm (Figure 1). Opioid-dependence disorder is chronic and relapsing,4 and the mortality rate and rates of psychiatric and physical comorbidity are high.5-7 The Global Burden of Disease 2010 study estimated that opioid dependence accounted for 9.2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide.7 According to estimates from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 33 million people use opioids worldwide for nonmedical purposes.8 In Europe, the number of opioid users is estimated at 1.3 million people, and opioids are involved in 82% of fatal drug intoxications.5 Prevalence rates of opioid use in Europe appear to have decreased over the past few years.9 Also, opioids other than heroin, eg, methadone (MET), buprenorphine (BUP), and fentanyl, have rather become the drugs of choice.9 From 2002 to 2013, the rate of heroin use increased in the United States (US) by 62%. 10 In a 2014 survey in the US, about 914 000 individuals had used heroin in the past year and about 4.3 million people had used prescription opioids for nonmedical reasons.11 From 2001 to 2013, related deaths increased threefold12; many of these deaths were a result of accidental poisoning of children.13

Figure 1. Factors contributing to the risk of developing a substance-use disorder.

Opioid maintenance treatment is a well-established first-line approach for opioid dependence,14 Oral MET, BUP, or the combination of BUP and naloxone are frequently used.15-18 The efficacy of both MET and BUP is proven.16,19,20 A few long-term studies have been performed, mostly in patients in opioid maintenance.21,22 Other available medications, such as oral or depot naltrexone, slow-release oral morphine,23 and injectable MET or heroin24 are not part of this review.

Search strategy

This paper is an extension of previous work on the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for treatment of opioid dependence.17 A PubMed search was performed with the search terms “opioid dependence,” “buprenorphine,” and “treatment” to identify additional and recent publications.

BUP in opioid maintenance treatment

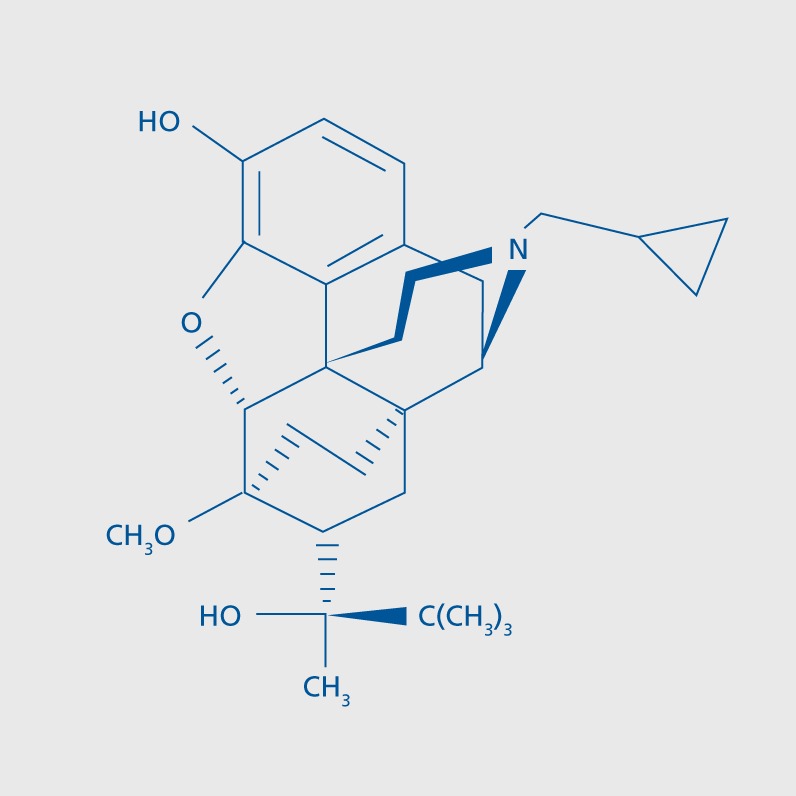

MET, BUP, and BUP/naloxone are well-established first-line treatments for opioid dependence.14,17,25-28 For comprehensive reviews on this issue, see Mammen and Bell15 and Yokell et al.29 In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved BUP in October 2002 as a treatment for opioid addiction. The chemical structure of BUP is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Chemical structure of buprenorphine.

Pharmacology

Because of the rapid metabolization of BUP and because it is subject to extensive first-pass liver metabolism, bioavailability is low after oral administration, and BUP tablets are given sublingually. Unlike MET, BUP is a partial agonist at the Li-opioid receptor and an antagonist at the K-opioid receptor; after sublingual administration, it has a long half-life (24 to 60 hours).30 Its pharmacological profile is unique and differs from that of full opioid agonists. In the induction phase, BUP may precipitate withdrawal symptoms.31

The induction and titration phase (which is often too rapid, causing side effects, opioid withdrawal, and, consequently, low retention, or too slow, resulting in a significant dropout rate) for BUP is of special relevance for treatment retention and varies between countries.32,33 For opioid maintenance therapy, BUP is usually started at 2 to 4 mg/day14 and can be increased by 2 to 4 mg/day. Many clinicians restrict the maximum dose on day 1 to 4 to 8 mg, although higher doses (16 mg) than the usually recommended maximum of 8 mg/day have been proposed34,35; the maximum dose used on day 1 in most studies is 8 mg.36 The typical dosages for maintenance treatment are 8-16 mg/day (FDA dosing limit: 24 mg/day).14

In Europe, BUP is available in two forms: a tablet with only BUP and one with a combination of BUP and the opioid antagonist naloxone in a 4:1 ratio (ie, BUP 2 mg/naloxone 0.5 mg or BUP 8 mg/naloxone 2 mg). Naloxone has poor sublingual but good parenteral bioavailability; its elimination half-life in plasma is approximately 30 minutes.37 The bioavailability of naloxone after sublingual administration is low enough as to not cause severe withdrawal symptoms in highly opioid-dependent people. However, if a BUP or BUP/naloxone tablet is dissolved and administered intravenously, it precipitates an immediate opioid-withdrawal syndrome. This effect is thought to improve the safety of BUP by reducing its abuse potential. According to guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association (APA),25 the British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP),27 the WFSBP,17 a Swedish group,38 and others,26 the BUP/naloxone combination tablet reduces the risk of diversion significantly.25 However, although the combination tablet may reduce intravenous misuse, it probably does not completely eliminate it15 (for review, see ref 39).

BUP acts as a partial agonist at opioid receptors. It has a ceiling effect for respiratory depression at higher concentrations, which reduces the risk of overdose. Doses above 24 to 32 mg/day do not further increase its respiratory-depressant effect. Furthermore, if BUP metabolism is inhibited, the higher concentrations do not result in the toxicity effects typical of opioids, including respiratory depression.30 If metabolism is induced, BUP's high affinity for μ-opioid receptors may allow it to remain at the opioid receptor even as plasma concentrations decrease. One of the probable advantages of BUP over full opioid agonists is its milder withdrawal syndrome after treatment discontinuation.

Clinical aspects of BUP treatment

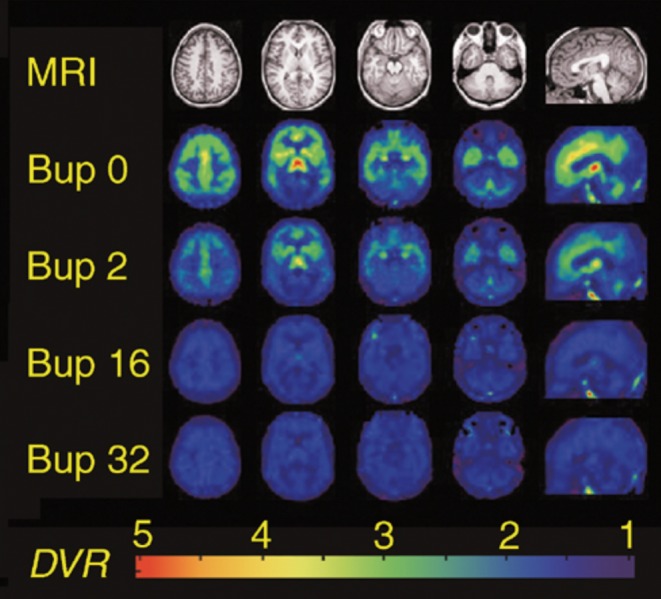

Clinical studies that compared MET (mainly in moderate dosages, ie, 50 to 60 mg/day) with BUP (12 to 16 mg/day) generally showed comparable efficacy of the two drugs and a modestly lower retention rate in BUP-treated patients.38,40,41 Optimal doses can be achieved in 2 to 3 days (8 to 16 mg/day to a maximum of 24 mg/ day)14; 16 mg/day of BUP suppresses 80% of the opioid receptor (Figure 3).42

Figure 3. Parametric images of μ-opioid receptor availability from a representative heroin-dependent volunteer during daily maintenance on buprenorphine placebo (row 2 from the top, Bup 0), 2 mg (Bup 2), 16 mg (Bup 16), and 32 mg (Bup 32). Images are scaled so that binding in the occipital cortex, an area devoid of u-receptors, is equal to 1. Four transverse sections from superior (column 1) to inferior (column 4) and one sagittal section (column 5) are shown, which correspond to T1-weighted anatomical MRI images (row 1). The pseudocolor scale depicts DVR values from 1 to 4. Reproduced from reference 42: Greenwald MK, Johanson CE, Moody DE, et al. Effects of buprenorphine maintenance dose on mu-opioid receptor availability, plasma concentrations, and antagonist blockade in heroin-dependent volunteers. Group. BUP, buprenorphine; DVR, direct volume rendering; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. Figure reproduced with permission from ref 42: Greenwald MK, Johanson CE, Moody DE, et al. Effects of buprenorphine maintenance dose on mu-opioid receptor availability, plasma concentrations, and antagonist blockade in heroin-dependent volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(11):2000-2009. © 2003 Nature Publishing Group.

Patient preferences and beliefs about opioids are important factors in the treating doctor's decision to use a certain drug. The interesting question about which kind of patient prefers MET and which prefers BUP was addressed in the SUMMIT trial (SUbutex vs Methadone Maintenance Trial), a prospective patient-preference study in 361 opioid-dependent individuals.43 BUP was given as a “rapid titration” at flexible doses (BUP: a mean of 6.9 mg at the end of day 1, 9.9 mg at the end of day 2, and 11.3 mg at the end of day 3; MET: 50.7 mg at the end of day 1, 63.8 mg at the end of day 2 and 69.6 mg at the end of day 3). Almost two-thirds of the patients (63%) chose MET, whereas the remaining patients (37%) chose BUP. In line with the common belief of many physicians, MET was chosen by participants whose substance abuse was more severe and who had psychiatric and physical problems. Although the MET group showed a higher retention rate, the likelihood of suppressing illicit opiate use and achieving detoxification was higher among those retained in the BUP group.

The side effects of BUP include respiratory depression, anxiety, sweating, constipation, headache, insomnia, nausea, dizziness, asthenia, and somnolence. BUP has a small risk for liver enzyme elevations or hepatotoxic effects, but less than previously thought.44 Unlike MET, BUP lacks both cardiotoxic effects and the risk of arrhythmias.45

Studies comparing BUP and MET

Historically, MET has been used more often than BUP in most European countries, with some exceptions (mainly France). The efficacy of opioid maintenance treatment is usually measured by the reduction in opioid use (drug-free urine screens) and the retention/ completion rate in treatment. Other important variables are safety (overdose, cardiotoxicity, etc), risk of diversion, reduction in criminality, and improvement of physical disorders and psychosocial functioning.

Studies comparing the effects of MET with BUP have produced mixed results: some show both drugs to be equally effective, whereas others demonstrate a higher retention rate with MET. BUP/naloxone clearly shows better retention than placebo or no treatment46 but worse retention than MET. However, only one of the studies in a recent systematic review evaluated retention in periods longer than 12 months.46

The results of a large, 24-week randomized multicenter study comparing the effects and treatment retention rates of MET and BUP in 1267 patients47 showed a higher retention rate with MET than with BUP (74% vs 46%); retention increased to 80% in the MET group when the maximum dose reached or exceeded 60 mg/day. Remarkably, in the BUP group, the completion rate showed a linear increase and reached a 60% retention rate at 30 to 32 mg/day. Interestingly, in the first 9 weeks, the number of positive opioid urine results among those remaining in treatment was significantly lower in the BUP than in the MET group. A lower dose (BUP <16 mg/day, MET <60 mg/day) was one of several factors associated with dropout. Consequently, the authors discussed that future investigations should use BUP doses above 32 mg/day to increase retention rates. Retention rate was also higher with MET than with BUP in other studies.48

A naturalistic long-term study in Germany of patients in opioid maintenance treatment (mean follow-up: 6 years)49 showed high overall retention rates in patients (see the section headed “Long-term outcome” below). Most of the patients were still being treated at the end of the study, and retention rates did not differ between MET and BUP.

Other studies also emphasize the relevance of dose. In fixed-dose studies, BUP is less effective at lower doses than at higher ones.16 A meta-analysis of 21 randomized clinical studies also (indicated that the retention rate is better at a higher dose (16 to 32 mg/day) than at a lower one (<16 mg/day).50 The question of dosing was also studied by Jacobs et al.51 A total of 740 patients were started on BUP at a flexible dose. Outcomes were better in patients who received higher BUP doses in the induction phase (first 7 days) and were significantly better in participants receiving >16 mg/day on day 28 than in those receiving <16 mg/day.

Future trends - BUP depot/implant

The development of novel opioids and opioid formulations is one goal to fight the current opioid crisis, especially in the US.52 In May 2016, a 6-month buprenorphine subdermal implant (Probuphine) was approved in the US for the maintenance treatment of opioid dependence in people who showed sustained, prolonged clinical stability at doses of no more than 8 mg/day sublingual BUP. First studies53-55 indicate that the BUP implant shows noninferiority or equal effects to sublingual BUP. A depot of long-acting implant formulations may lower the risk of diversion and facilitate the clinical management of otherwise stable opioid-dependent patients. This formulation is not yet available in Europe. Recent data on a weekly BUP depot preparation, CAM2038 (24 mg and 32 mg), indicate that it is safely tolerated and produces immediate and sustained opioid blockade and opioid withdrawal suppression.56

Drug interactions with BUP

BUP can interact with other drugs as a result of altered pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamic interactions. The former are related to inhibition or induction of hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and effects on glucuronidation, drug transporter function (P-glycoprotein), and drug absorption57,58; other possible mechanisms, eg, changes in blood-brain-barrier permeability, remain hypothetical. The latter include the additive effects of two drugs that have similar actions.

Pharmacokinetic interactions

These interactions are more complex than pharmacodynamic ones. Most drugs are metabolized in the liver and interactions of a drug with BUP may change the rate of metabolism of either drug and subsequently alter plasma concentrations, among other things. Inhibitors of the CYP enzymes may cause increases in plasma drug concentrations, with associated risks of toxicity or overdose. Drugs that induce synthesis of CYP enzymes may lead to reduced drug efficacy or withdrawal.

BUP is generally believed to have fewer interactions than MET, for both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic reasons.59 After BUP is absorbed sublingually, CYP3A4 and to a lesser extent CYP2C8 convert and N-dealkylate it to the active metabolite norbuprenorphine. Subsequently, both BUP and norbuprenorphine are metabolized further by uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), mostly UGT 1A3 but also 2B6 and 1A1.60 BUP does not significantly induce or inhibit P450 enzymes (and neither does MET), but it may compete with drugs that are metabolized by the same pathways. BUP is a weak inhibitor of CYP3A4.

Although inhibitors of CYP3A4 may result in increased BUP concentrations in plasma, BUP's effect as a partial agonist may reduce the chance of opioid toxicity and overdose. Nevertheless, clinicians are recommended to monitor patients for side effects, including sedation or complications, such as liver toxicity, and monitoring is indicated if inhibitors of BUP metabolism are coadministered. Inducers of CYP3A4 may increase BUP metabolism, thus decreasing plasma concentrations and perhaps leading to opioid withdrawal; withdrawal is unlikely, however, because of the ceiling effect and half-life of BUP at the opioid receptor. Furthermore, the active metabolite norbuprenorphine may also prevent opioid withdrawal. In vitro studies have shown an inhibitory effect of BUP and norbuprenorphine on the CYP2D6 system, but this effect is not relevant in humans. Norbuprenorphine is also of relevance for BUP toxicity, including respiratory depression.

Pharmacodynamic interactions

BUP shows pharmacodynamic interactions primarily with other depressants of the central nervous system, including alcohol, opioids, and psychotropic drugs. The toxicological and forensic literature is clear: BUP-related deaths are almost exclusively associated with coconsumption of other psychotropic agents or drugs.

Safety issues

A scholarly review on 58 prospective studies of samples with opioid dependence61 showed high mortality rates (all-cause mortality: 2.09/100 person years [PY]) but confirmed that, overall, maintenance treatment significantly lowers rates compared with untreated heroin dependence (1% to 3% deaths/year). The review found that most patients died from overdose and that risk was higher in males and during out-of-treatment periods.

Opioid-related deaths, especially from prescription opioids, such as fentanyl, have risen sharply in the US in particular.62 It is generally accepted that overdoses related to consumption solely of BUP are rare63-65 and that the risk for BUP-treated patients is lower than for MET-treated patients. The lower risk for respiratory depression in BUP-treated people must be balanced against the risk for other side effects, patients' preferences, and the somewhat lower retention rate found in some trials comparing BUP with MET.22

Many medications, including full opioid agonists, such as MET, may cause prolongation of the ratecorrected QT (QTc) interval in the electrocardiogram (ECG), arrhythmias, and torsades de pointes and may carry a risk of sudden cardiac death.66 BUP appears to be safer in this respect (see above).

Long-term outcome

A large naturalistic, nationally representative, prospective follow-up study conducted in Germany examined the 6-year outcome in opioid-dependent patients on maintenance treatment (N=2694); it consisted of three phases (baseline, 1 year, 5 to 7 years) and evaluated a nationwide representative sample of clinicians and the opioid-dependent patients in their care. The study found an annual mortality rate of about 1.9% for both MET- and BUP-treated patients.49 Mortality rates were 1.2% (n=28/2284) after 1 year and 5.7% (n=131/2284) after 6 years. Rates did not differ between males and females.18 The most frequent causes of death were physical disorders (n=57, 36.6%; eg, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS [n=14], cancer [n=6], cardiovascular events [n=6; n=5 (0.3%) in the MET group and n=1 (0.2%) in the BUP group, not significant]), drug overdose (28.3%, eg, heroin, benzodiazepines, cocaine; n=6/37 for polyintoxication including the substitution drug) and suicide (16%). Fatal overdose of MET or BUP alone was almost never the sole cause of death (n=2, 1.5%), and interactions of MET or BUP with other drugs were also quite rare (n=6, 6.1%). The majority of patients who died were not receiving maintenance treatment (n=73, 55.7%) in the weeks before their death, either because the physician had decided to stop treatment or because the patient had stopped visiting the physician. In line with this finding is that overdose rates seemed to be higher for those who died outside treatment. Among the 58 patients (44.3%) who died while receiving maintenance treatment, 52/1690 treated with MET at baseline were receiving MET and 6/578 treated with BUP at baseline were receiving BUP. Thus, the mortality risk was significantly lower in the BUP patients than in the MET patients. Overall retention rate was similar for both medications over time.

In comparison with findings of an earlier metaanalysis,61 in the 6-year follow-up study, the mean crude annual mortality rate of about 1.0% was comparably low. In contrast with the findings of the meta-analysis, however, in the 6-year follow-up study, the most frequent cause of death was physical illness, followed by fatal overdose or intoxication with multiple substances. BUP and MET were rarely (1.5%) involved in premature death. Suicide (16%) was another frequent cause of death, but accidents or other violent causes were uncommon (4.6%). Of interest is that the annual mortality rate decreased only modestly over time; it was highest in the first year, but thereafter the decrease was not as large as might have been expected. This finding is in line with other long-term studies that also found a continued high rate of mortality in opioid-dependent patients.67

As mentioned above, in the 6-year follow-up study, just over half of patients who died were no longer receiving maintenance treatment at the time of their death. As in earlier studies,6 discontinuation for any reason and not being in treatment were key predictors of death. This study also confirmed the well-known predictors of death identified in earlier studies with shorter follow-up periods,61 eg, unemployment, greater age, longer use of opioids, and comorbid mental or physical disorders.

The lower premature death rate at the 6-year follow-up in patients treated with BUP was remarkable,18 and BUP was shown to be a significant predictor for survival. This finding is consistent with other studies, in particular with French and German forensic autopsy data that indicate a low mortality risk for BUP.68,69 Cornish et al70 examined the risk of death in a large cohort of patients and found a crude mortality rate of 0.7/100 PY in patients receiving treatment and of 1.3/100 PY in patients out of treatment. Unlike in the German 6-year follow-up study, mortality risk was twice as high in men and higher during the first 2 weeks of treatment.70 Outcome and mortality may differ because of differences in the samples studied or because severely affected patients were allocated to the MET group, which may be indicated by a higher rate of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses at baseline.71

Retention is essential for treatment outcome. Overall, the dropout rate for drug therapies is high. Gossop and Marsden72 estimated the dropout rate to be about 40%, but some authors report significantly higher rates. Gossop and Marsden72 also reported optimistic abstinence rates of 51 % at 6 months after discharge from inpatient treatment. However, most international studies have shown much lower abstinence rates of 20% to a maximum of 30% in the long term. Large studies were presented by Simpson and Sells73,74 and Hubbard et al75 as part of the Treatment Outcome Prospective Study, a 5-year follow-up study. Depending on the definition used in the study, in the first year of treatment often 30% to 50% of the patients were drug free.

Psychotherapy in BUP-maintained patients

What kind of psychosocial therapies work in opioid maintenance therapy? In particular, motivational interviewing and contingency management are important evidence-based forms. These forms of psychotherapy have the highest level of evidence and have also been investigated in opioid dependence. Several studies found positive results for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which is also generally used as the basis for dependence-specific forms of psychotherapy. Long-term studies73,74 and meta-analyses have evaluated the efficacy of psychosocial therapies. Of particular importance is the meta-analysis by Dutra et al76—who found that contingency management, relapse prevention, general CBT, and treatments combining CBT and contingency management have moderate effect sizes—and several Cochrane analyses77 on the efficacy of psychosocial therapies in combination with substitution treatment. The APA guidelines25 emphasize among other things that after inpatient treatment, continued treatment as an outpatient is important for drug-dependent patients. A comprehensive meta-analysis on the treatment of opioid dependence was also published by Berglund et al.78 This meta-analysis examined 24 methodologically sound studies and found that, overall, the psychotherapies showed moderately large effect sizes in comparison with the control groups. Purely supportive therapies are probably ineffective.

The number of available studies on psychosocial interventions in conjunction with opioid maintenance treatment is much more limited.79,80 Two Cochrane analyses have been published,81,82 but most of the studies were conducted on MET maintenance. Again, CBT and contingency management have the best evidence. Three studies examined the efficacy of CBT patients in BUP treatment,83-85 with mixed results. In their systematic review on the available relevant studies, Dugosh et al79 concluded that the evidence for efficacy of psychosocial interventions in BUP treatment is less robust than for MET. Retention and completion rates and opioid use in general improved in some of the studies. A recent studycomparing CBT, contingency management, and the combination of both with no additional treatment in BUPtreated patients did not find any differences between groups.84 Hie optimal psychosocial support for BUP-treated people remains a challenging topic of research.

Many clinicians—and authorities—consider adequate psychosocial treatment to be mandatory in patients in opioid maintenance treatment, despite the limited success rates. For many patients, rapid induction of treatment may be crucial to reduce the overdose risk. Interestingly, a recent pilot study examined the effects of “interim” BUP treatment in reducing illicit opioid use among 50 people on waiting lists for entry into treatment86 and found that illicit opioid use was significantly less in patients on interim BUP than in those on the waiting list.

Outlook

Although psychosocial treatments are effective in opioid dependence,76 opioid maintenance treatment is a well-established first-line approach16,87 and is recommended by numerous treatment guidelines.17,25-28 Patients out of treatment have a much higher mortality rate than those in maintenance treatment.88

A significant number of treatment studies have been performed in opioid dependence, including some longterm studies in opioid-dependent individuals67,89 and some short- to mid-term clinical experimental studies.16,87 Most studies indicate that opioid-dependent patients with and without maintenance therapy have a high risk for inpatient treatments and detoxification.90 A 15-year follow-up of an Israeli sample (N=613)6 found that patients staying longer in treatment had a lower mortality rate. This finding is also supported by many other clinical studies.

In conclusion, BUP and BUP/naloxone are safe and effective for treating opioid dependence. In addition to MET and BUP, the BUP/naloxone combination is a first-line treatment option. The combination drug mayhave some advantages and disadvantages compared with MET and BUP (Table I). The novel BUP implant may be an interesting alternative for otherwise more stable patients.

TABLE 1. Possible advantages of buprenorphine over fuii opioid agonists. BUP, buprenorphine.

| Level of evidence | |

| Possible advantages | |

| Better safety, less respiratory depression | Strong |

| Better suppression of illicit opioid use | Some; inconclusive |

| Less sedation, better social functioning | Some; inconclusive |

| Easier progressto detoxification | None |

| Less risk of diversion (BUP/naloxone combination) | Some |

| Fewer pharmacological interactions | Modest |

| Less cardiotoxicity | Some |

| Less alcohol use | Some; inconclusive |

| Antidepressant effect91 | Some |

| Less sweating | Some |

| Possible disadvantages | |

| Can precipitate withdrawal at induction | Strong |

| Unpleasant taste | Some |

| Lower retention rate | Some |

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Jacquie Klesing, Boardcertified Editor in the Life Sciences (ELS), for editing assistance with the manuscript. No funding was used in the preparation of this review. For the past 5 years, MS has worked as a consultant or has received research grants from Lundbeck, Sanofi Aventis, Reckitt Benckiser/lndivior, Servier, and Novartis.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuckit MA. Treatment of opioid-use disorders. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):357–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1604339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. European Drug Report 2016: Trends and Developments. Available at: http:// www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/edr/trends-developments/2014. Published May 2016. Accessed June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peles E., Schreiber S., Adelson M. 15-Year survival and retention of patients in a general hospital-affiliated methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) center in Israel. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107(2-3):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degenhardt L., Charlson F., Mathers B., et al The global epidemiology and burden of opioid dependence: results from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1320–1333. doi: 10.1111/add.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2016. New York, NY: United Nations. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. European Drug Report 2014: Trends and Developments. Available at: http:// www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/edr/trends-developments/2014. Published May 2014. Accessed June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones CM., Logan J., Gladden RM., Bohm MK. Vital signs: demographic and substance use trends among heroin users - United States, 2002-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal VJkly Rep. 2015;64(26):719–725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50); 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose death rates. Available at: https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdosedeath-rates. Revised January 2017. Accessed March 31, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imtiaz S., Shield KD., Fischer B., Rehm J. Harms of prescription opioid use in the United States. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2014;9:43. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-9-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kampman K., Jarvis M. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) National Practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358–367. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mammen K., Bell J. The clinical efficacy and abuse potential of combination buprenorphine-naloxone in the treatment of opioid dependence. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(15):2537–2544. doi: 10.1517/14656560903213405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattick RP., Breen C., Kimber J., Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soyka M., Kranzler HR., van den Brink W., Krystal J., Moller HJ., Kasper S. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of substance use and related disorders. Part 2: Opioid dependence. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12(3):160–187. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.561872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soyka M., Trader A., Klotsche J., et al Six-year mortality rates of patients in methadone and buprenorphine maintenance therapy: results from a nationally representative cohort study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):678–680. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31822cd446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connock M., Juarez-Garcia A., Jowett S., et al Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(9):1–171, iii-iv. doi: 10.3310/hta11090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakko J., Svanborg KD., Kreek MJ., Heilig M. 1-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9358):662–668. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hser Yl., Evans E., Grella C., Ling W., Anglin D. Long-term course of opioid addiction. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23(2):76–89. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hser Yl., Evans E., Huang D., et al Long-term outcomes after randomization to buprenorphine/naloxone versus methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction. 2016;111(4):695–705. doi: 10.1111/add.13238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck T., Haasen C., Verthein U., et al Maintenance treatment for opioid dependence with slow-release oral morphine: a randomized cross-over, non-inferiority study versus methadone. Addiction. 2014;109(4):617–626. doi: 10.1111/add.12440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strang J., Groshkova T., Uchtenhagen A., et al Heroin on trial: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials of diamorphine-prescribing as treatment for refractory heroin addictiondagger. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(1):5–14. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.149195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleber HD., Weiss RD., Anton RF Jr., et al Treatment of patients with substance use disorders, second edition. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(4 suppl):5–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.New South Wales Department of Health. Opioid treatment program: clinical guidelines for methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Sydney, Australia: NSW Government. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lingford-Hughes AR., Welch S., Peters L., Nutt DJ. BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(7):899–952. doi: 10.1177/0269881112444324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the psychosocial assisted pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yokell MA., Zaller ND., Green TC., Rich JD. Buprenorphine and buprenorphine/naloxone diversion, misuse, and illicit use: an international review. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(1):28–41. doi: 10.2174/1874473711104010028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh SL., Preston KL., Stitzer ML., Cone EJ., Bigelow GE. Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: ceiling effects at high doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55(5):569–580. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh SL., June HL., Schuh KJ., Preston KL., Bigelow GE., Stitzer ML. Effects of buprenorphine and methadone in methadone-maintained subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1995;119(3):268–276. doi: 10.1007/BF02246290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auriacombe M., Fatseas M., Dubernet J., Daulouede JP., Tignol J. French field experience with buprenorphine. Am J Addict. 2004;13(suppl 1):S17–S28. doi: 10.1080/10550490490440780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quaglio G., Pattaro C., Gerra G., et al Buprenorphine in maintenance treatment: experience among Italian physicians in drug addiction centers. Am J Addict. 2010;19(3):222–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunderson EW., Levin FR., Rombone MM., Vosburg SK., Kleber HD. Improving temporal efficiency of outpatient buprenorphine induction. Am J Addict. 2011;20(5):397–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saxon AJ., Ling W., Hillhouse M., et al Buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone effects on laboratory indices of liver health: a randomized trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128(1-2):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liebschutz JM., Crooks D., Herman D., et al Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1369–1376. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiang CN., Hawks RL. Pharmacokinetics of the combination tablet of buprenorphine and naloxone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(2 suppl):S39–S47. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kakko J., Gronbladh L., Svanborg KD., et al A stepped care strategy using buprenorphine and methadone versus conventional methadone maintenance in heroin dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(5):797–803. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lofwall MR., Walsh SL. A review of buprenorphine diversion and misuse: the current evidence base and experiences from around the world. J Addict Med. 2014;8(5):315–326. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schottenfeld RS., Pakes JR., Oliveto A., Ziedonis D., Kosten TR. Buprenorphine vs methadone maintenance treatment for concurrent opioid dependence and cocaine abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(8):713–720. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200041006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soyka M., Zingg C., Koller G., Kuefner H. Retention rate and substance use in methadone and buprenorphine maintenance therapy and predictors of outcome: results from a randomized study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11(5):641–653. doi: 10.1017/S146114570700836X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenwald MK., Johanson CE., Moody DE., et al Effects of buprenorphine maintenance dose on mu-opioid receptor availability, plasma concentrations, and antagonist blockade in heroin-dependent volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(11):2000–2009. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinto H., Maskrey V., Swift L., Rumball D., Wagle A., Holland R. The SUMMIT trial: a field comparison of buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39(4):340–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soyka M., Backmund M., Schmidt P., Apelt S. Buprenorphine-naloxone treatment in opioid dependence and risk of liver enzyme elevation: results from a 12-month observational study. Am J Addict. 2014;23(6):563–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kao DP., Haigney MC., Mehler PS., Krantz MJ. Arrhythmia associated with buprenorphine and methadone reported to the Food and Drug Administration. Addiction. 2015;110(9):1468–1475. doi: 10.1111/add.13013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Timko C., Schultz NR., Cucciare MA., Vittorio L., Garrison-Diehn C. Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: a systematic review. J. Addict Dis. 2016;35(1):22–35. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2016.1100960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hser Yl., Saxon AJ., Huang D., et al Treatment retention among patients randomized to buprenorphine/naloxone compared to methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction. 2014;109(1):79–87. doi: 10.1111/add.12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burns L., Gisev N., Larney S., et al A longitudinal comparison of retention in buprenorphine and methadone treatment for opioid dependence in New South Wales, Australia. Addiction. 2015;110(4):646–655. doi: 10.1111/add.12834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soyka M., Strehle J., Rehm J., Buhringer G., Wittchen HU. Six-year outcome of opioid maintenance treatment in heroin-dependent patients: results from a naturalistic study in a nationally representative sample. Eur Addict Res. 2017;23(2):97–105. doi: 10.1159/000468518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fareed A., Vayalapalli S., Casarella J., Drexler K. Effect of buprenorphine dose on treatment outcome. J Addict Dis. 2012;31(1):8–18. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2011.642758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacobs P., Ang A., Hillhouse MP., et al Treatment outcomes in opioid dependent patients with different buprenorphine/naloxone induction dosing patterns and trajectories. Am J Addict. 2015;24(7):667–675. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volkow ND., Collins FS. The role of science in addressing the opioid crisis. N Engl J Med. 2017 May 13. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1706626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenthal RN., Ling W., Casadonte P., et al Buprenorphine implants for treatment of opioid dependence: randomized comparison to placebo and sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone. Addiction. 2013;108(12):2141–2149. doi: 10.1111/add.12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenthal RN., Lofwall MR., Kim S., Chen M., Beebe KL., Vocci FJ. Effect of buprenorphine implants on illicit opioid use among abstinent adults with opioid dependence treated with sublingual buprenorphine: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(3):282–290. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ling W., Casadonte P., Bigelow G., et al Buprenorphine implants for treatment of opioid dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1576–1583. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walsh SL., Comer SD., Lofwall MR., et al Effect of Buprenorphine Weekly Depot (CAM2038) and Hydromorphone Blockade in Individuals With Opioid Use Disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jun 22. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCance-Katz E. Drug-Drug Interactions in Opioid Therapy. 7th ed. London, UK: PCM Healthcare Ltd; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karan LD., McCance-Katz E., Zajicek A. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic principles. In: Ries RK, Fiellin DA, Miller SC, eds. Principles of Addiction Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/ Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:67–84. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gruber VA., McCance-Katz EF. Methadone, buprenorphine, and street drug interactions with antiretroviral medications. Curr HIVIAIDS Rep. 2010;7(3):152–160. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0048-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saber-Tehrani AS., Bruce RD., Altice FL. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions and adverse consequences between psychotropic medications and pharmacotherapy for the treatment of opioid dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37(1):1–11. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.540279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Degenhardt L., Bucello C., Mathers B., et al Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction. 2011;106(1):32–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rudd RA., Aleshire N., Zibbell JE., Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths-United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal WklyRep. 2016;64(50-51):1378–1382. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Auriacombe M., Franques P., Tignol J. Deaths attributable to methadone vs buprenorphine in France. JAMA. 2001;285(1):45. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bell JR., Butler B., Lawrance A., Batey R., Salmelainen P. Comparing overdose mortality associated with methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104(1-2):73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kintz P. Deaths involving buprenorphine: a compendium of French cases. Forensic Sci int. 2001;121(1-2):65–69. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(01)00454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pani PP., Trogu E., Maremmani I., Pacini M. QTc interval screening for cardiac risk in methadone treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD008939. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008939.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bjornaas MA., Bekken AS., Ojlert A., et al A 20-year prospective study of mortality and causes of death among hospitalized opioid addicts in Oslo. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pirnay S., Borron SW., Giudicelli CP., Tourneau J., Baud FJ., Ricordel I. A critical review of the causes of death among post-mortem toxicological investigations: analysis of 34 buprenorphine-associated and 35 methadone-associated deaths. Addiction. 2004;99(8):978–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Soyka M., Apelt SM., Lieb M., Wittchen HU. One-year mortality rates of patients receiving methadone and buprenorphine maintenance therapy: a nationally representative cohort study in 2694 patients. J Clin PsychopharmacoL. 2006;26(6):657–660. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000245561.99036.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cornish R., Macleod J., Strang J., Vickerman P., Hickman M. Risk of death during and after opiate substitution treatment in primary care: prospective observational study in UK General Practice Research Database. BMJ. 2010;341:c5475. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lieb M., Wittchen HU., Palm U., Apelt SM., Siegert J., Soyka M. Psychiatric comorbidity in substitution treatment of opioid-dependent patients in primary care: prevalence and impact on clinical features. Heroin Addict RelatClin Probl. 2010;12(4):5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gossop M., Marsden J. Assessment and treatment of opiate problems. Baillieres Clin Psychiatry. 1996;2:445–459. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Simpson DD., Sells SB. Effectiveness of treatment for drug abuse: an overview of the DARP Research Program. Adv Alcohol Subst Abuse. 1982;2:27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Simpson DD., Sells SBe. Opioid Addiction and Treatment: A 12-year FollowUp. Malabar, FL: Robert E. Kreiger. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hubbard RL., Marsden ME., Rachal JV., Harwood HJ., Cavanaugh ER., Ginzburg HM. Drug Abuse Treatment: A National Study of Effectiveness. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press; 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dutra L., Stathopoulou G., Basden SL., Leyro TM., Powers MB., Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Amato L., Minozzi S., Davoli M., Vecchi S., Ferri M., Mayet S. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 Apr;:CD004147. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004147.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Berglund M., Thelander S., Jonsson E. Treating Alcohol and Drug Abuse: An Evidence Based Review. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dugosh K., Abraham A., Seymour B., McLoyd K., Chalk M., Festinger D. A systematic review on the use of psychosocial interventions in conjunction with medications for the treatment of opioid addiction. J Addict Med. 2016;10(2):93–103. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Day E., Mitcheson L. Psychosocial interventions in opiate substitution treatment services: does the evidence provide a case for optimism or nihilism? Addiction. 2017;112(8):1329–1336. doi: 10.1111/add.13644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Amato L., Minozzi S., Davoli M., Vecchi S. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):CD004147. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004147.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Amato L., Minozzi S., Davoli M., Vecchi S. Psychosocial and pharmacological treatments versus pharmacological treatments for opioid detoxification. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD005031. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005031.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fiellin DA., Barry DT., Sullivan LE., et al A randomized trial of cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care-based buprenorphine. Am J Med. 2013;126(1):74.e11–74.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ling W., Hillhouse M., Ang A., Jenkins J., Fahey J. Comparison of behavioral treatment conditions in buprenorphine maintenance. Addiction. 2013;108(10):1788–1798. doi: 10.1111/add.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moore BA., Barry DT., Sullivan LE., et al Counseling and directly observed medication for primary care buprenorphine maintenance: a pilot study. J Addict Med. 2012;6(3):205–211. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182596492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sigmon SC., Ochalek TA., Meyer AC., et al Interim buprenorphine vs. waiting list for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(25):2504–2505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1610047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mattick RP., Breen C., Kimber J., Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD002209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002209.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Evans E., Li L., Min J., et al Mortality among individuals accessing pharmacological treatment for opioid dependence in California, 2006-10. Addiction. 2015;110(6):996–1005. doi: 10.1111/add.12863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hser Yl., Anglin D., Powers K. A 24-year follow-up of California narcotics addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(7):577–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820190079008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nosyk B., Li L., Evans E., et al Utilization and outcomes of detoxification and maintenance treatment for opioid dependence in publicly-funded facilities in California, USA: 1991-2012. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;143:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Karp JF., Butters MA., Begley AE., et al Safety, tolerability, and clinical effect of low-dose buprenorphine for treatment-resistant depression in midlife and older adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):e785–e793. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]