Abstract

Objectives

Study trends in the treatment of atrial septal defects (ASD).

Background

Concern for device erosion following transcatheter treatment of ASD (TC-ASD) led in 2012 to a US FDA panel review and changes in the instructions for use (IFU) of the Amplatzer Septal Occluder (ASO) device. No studies have assessed the effect of these changes on real-world practice.

Methods

A retrospective observational study was performed using data from the Pediatric Health Information Systems Database of all patients with isolated ASD undergoing either TC-ASD or operative ASD closure (O-ASD) from 1/1/2007 to 9/30/2015, hypothesizing that the propensity to pursue O-ASD increased beginning in 2013.

Results

6,392 cases from 39 centers underwent ASD closure (82% TC-ASD). Adjusting for patient factors, between 2007 and 2012, the probability of pursuing O-ASD decreased (OR: 0.95 per year, p=0.03). This trend reversed beginning in 2013, with the probability of O-ASD increasing annually (OR: 1.21, p=0.006). There was significant between-hospital variation in the choice between TC-ASD and O-ASD (median odds ratio: 2.79, p<0.0001). The age of patients undergoing ASD closure (regardless of method) decreased over the study period (p=0.04). Cost of O-ASD increased over the study period, while cost of TC-ASD and LOS for both O-ASD and TC-ASD was unchanged.

Conclusion

Though TC-ASD remains the predominant method of ASD closure, the propensity to pursue O-ASD has increased significantly following changes in IFU for ASO. Further research is necessary to determine what effect this has on outcomes and resource utilization.

Keywords: outcomes research, administrative database, pediatric cardiology, heart catheterization

Introduction

Ostium secundum atrial septal defects (ASD) are a relatively common form of congenital heart disease with an incidence of 6 to 10 per 10,000 live births(1). Since transcatheter device closure of ASD (TC-ASD) was first reported by King and Mills in 1976(2) device occlusion of ASD has been widely adopted. TC-ASD with the Amplatzer Septal Occluder and Gore Helex Septal Occluder devices has comparable rates of technical success and risk of adverse events when compared to operative closure of ASD (O-ASD)(3–8). Concern has been raised over the last decade regarding the risk of erosion of the Amplatzer Septal Occluder (ASO) device, a rare but potentially catastrophic adverse outcome(9–14). In 2012, a United States Food and Drug Administration panel review was convened highlighting the potential risk of erosion in patients following TC-ASD, especially those with deficient retro-aortic rim (< 5mm). In response to this, the manufacturer’s Indications For Use (IFU) for the ASO were changed, defining deficient retro-aortic rim (<5 mm) as a relative contraindication to TC-ASD(15–17). The effect of this controversy on practice patterns has not, to our knowledge, been studied previously.

We performed a multicenter retrospective observational study using data from the Pediatric Health Information Systems (PHIS) Database to study changes in patterns of ASD closure at primary pediatric hospitals in the United States from 2007 to 2015. We hypothesized that concern for erosion and controversy regarding TC-ASD would have resulted in measurable changes in patterns of ASD closure over the study period, specifically that beginning in 2013 there would be an increasing proportion of operative ASD closure (relative to transcatheter device closure procedures). As exploratory analyses, we also studied whether there were changes in the age of patients undergoing ASD closure and the cost and length of stay following ASD closure.

Methods

Data Source

The PHIS database is an administrative database that contains data from inpatient, emergency department, ambulatory surgery, and observation encounters from 47 not-for-profit, tertiary care pediatric hospitals in the United States. These hospitals are affiliated with the Children’s Hospital Association (Overland Park, KS). Data quality and reliability are assured through a joint effort between the Children’s Hospital Association and participating hospitals. The data warehouse function for the PHIS database is managed by Truven Health Analytics (Ann Arbor, MI). For the purposes of external benchmarking, participating hospitals provide discharge/encounter data including demographics, diagnoses, and procedures. The majority of these hospitals also submit resource utilization data (e.g. pharmacy products, radiologic studies, and laboratory studies) to PHIS. Data are de-identified at the time of data submission and are subjected to a number of reliability and validity checks. A data-use agreement was signed between study investigators and Children’s Hospital Association. The institutional review board of Children’s National Medical Center reviewed the proposed project and determined that it did not represent human subjects research in accordance with the Common Rule (45 CFR 46.102(f)).

Study Population

We included children and adults of all ages undergoing either operative or transcatheter closure of atrial septal defect at any of the 47 PHIS centers between 1/1/2007 and 9/30/2015. Subjects with additional anatomic cardiac disease were excluded, restricting analyses to isolated ASD. Subjects were identified by International Classification of Disease, ninth revision code (ICD-9) as having an ASD (ICD-9: 745.5) and divided between those undergoing 1) trans-catheter ASD closure (TC-ASD) (ICD-9: 35.52) or 2) open heart surgery for ASD closure (O-ASD) (ICD-9: 35.51, 35.61, or 35.71). We excluded subjects from centers reporting 1) fewer than 25 cardiac catheterization or cardiac operative procedures per year over the study period or 2) reporting cardiac catheterization procedures and cardiac operations less than three of the nine years during the study period, as previously described(18–21). This was intended to restrict analysis to centers with stable reporting practices and procedural volumes.

Study Measures

Data were extracted from the PHIS database by direct query using ICD-9 codes for diagnoses and procedures as well as Clinical Transaction Codes (CTC) for pharmaceutical products. Patient-level data included subject age, sex, race (white, black, Asian, other, or missing), insurance payer (private, Medicaid, other governmental insurance, or other), presence of genetic syndrome, presence of non-cardiac congenital anomalies, history of prematurity. Medical comorbidities were divided by system as has been previously described(22). Co-morbidities with prevalence less than 1% were grouped together as “other medical condition.”

As described previously, several steps were undertaken to generate cost data comparable between hospitals and across the entire study period(5,19,20). PHIS receives billing data directly from hospitals, including itemized charges. PHIS converts these charges to costs using hospital and department specific ratios of costs to charges. Costs are also adjusted for regional wage-price indices to provide costs comparable between hospitals across the country. Total costs (including device cost) for an entire hospitalization/encounter can be retrieved within the confines of our data-use agreement, but more detailed cost-reports (i.e. department-level or itemized costs) are not released. We further adjusted cost data to account for inflation using the Consumer Price Index for medical care, as compiled by the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/dsrv). All costs are expressed as year 2015 United States dollars (2015US$).

Analysis

The characteristics of the cohorts were described by calculating standard descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (range and inter-quartile range) as appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as percent (count). However, prior to analysis, we suspected that baseline characteristics (age, height, weight, insurance payer, and prevalence of chronic medical conditions) would differ between TC-ASD and O-ASD cohorts as has been described previously(5). Student’s T-test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, and Chi-squared tests were used to assess differences in distribution of baseline characteristics of O-ASD and TC-ASD cohorts.

Our primary goal was to study how the propensity to pursue TC-ASD or O-ASD changed over the study period. First, we measured the raw numbers of TC-ASD and O-ASD procedures changed over the study period. As described previously, we assessed the rates of both methods for ASD closure in several ways to provide complementary information about trends in ASD closure. These included: 1) the total number of ASD closure procedures as well as TC-ASD and O-ASD procedures in the study period annually, 2) the proportion of TC-ASD vs. O-ASD procedures, 3) the average number of each ASD closure procedure per center per year, and 4) the proportion of each hospital’s surgical or catheterization annual volume comprised of ASD closure procedures. Analysis of these outcomes was restricted to the period between 2007–2014 because only three quarters of 2015 was included in this study. Linear regression was used to assess for trends in each of these rates over the study period. The latter two measures were chosen to differentiate changes in practice vs. changes in procedural volume at the included centers over time. They provide complementary information about patterns of practice over the study period. The total number of patients with ASD in the population over the study period cannot be measured therefore neither can the incidence of either TC-ASD or O-ASD. In addition, the number of centers contributing data to PHIS has increased over the study period, so inference about trends based on these raw numbers is limited.

To overcome these limitations, we used multivariable mixed effects modeling to determine how the propensity to perform O-ASD (instead of TC-ASD) changed over the study period. This allowed us to adjust for patient level characteristics and clustering in behavior by hospital. Also, using date of procedure as a dependent variable increases statistical power (since it does not artificially divide the data into categories by year). It also allowed for inclusion of different numbers of hospitals over the study period without introducing bias. We hypothesized that the propensity to perform O-ASD would increase during the study period because of concern about erosion of transcatheter devices. In addition, the aforementioned FDA panel review and subsequent change in IFU for the ASO in 2012, represented a formal and very public manifestation of this concern and a potential inflection point in practice.

This analysis was accomplished by calculating multivariate models, in which the primary outcome was choice of O-ASD vs. TC-ASD and the primary exposure was date of ASD closure. The choice of date maximizes statistical power, allows for careful analysis of different patterns of change, and allows for inclusion of incomplete years of data without introducing bias. Because cohort identification is performed by ICD-9 code and there is no code for failed TC-ASD, it is not possible to assess for crossover in a single admission or between admissions. As a result this is an as-treated analysis. A mixed-effects generalized linear model was calculated using a logistic link. Fixed effects included age, sex, race, insurance payer, genetic syndrome and history of gastrointestinal, hematologic, neurological, pulmonary, or other condition. A random intercept for hospital was added to account for covariance within individual hospitals. To account for possible differences in hospital trends over time, a random slope for these factors was also added, but during analysis it was determined that it did not improve model fit in any models (data not shown). To test our hypothesis, our primary model included an inflection point at 1/1/2013, allowing for the overall slope to change after that date. Several additional models were also calculated to assess for alternative associations between date of operation and choice of TC-ASD vs. O-ASD, specifically by: 1) a model with no inflection points and 2) a model with an additional quadratic term to the model, and 3) a model with an inflection point added at the midpoint of the study period (May 19, 2011). These alternative models were calculated to insure that we did not incorrectly impose an inflection point based on our hypothesis and to study whether alternative relationships between time and the outcome of interest were present. Model fit was assessed using Akaike Information Criteria. To provide an interpretable representation of the choice between TC-ASD vs. O-ASD, conditional standardization was used to calculate the propensity for each by year over the study period (holding all other covariates at their mean or as their referent group).

In contrast to counting the total number of procedures, modeling the propensity of an individual patient to undergo O-ASD or TC-ASD mitigates hospitals joining PHIS during the study period. Longitudinal analysis of this kind, with date as the exposure, also has superior statistical power relative to analyses that divide the population into numbers of cases per year. Multivariable modeling allowed us to adjust for case-mix at individual centers, while the addition of a random intercept allowed us to measure whether there was significant inter-hospital variation between centers (independent of case-mix).

Measurement of inter-hospital variation was performed in two ways. First, a likelihood ratio test was applied to the full model and a model with the random intercept removed(20). This test of heterogeneity assessed whether there was statistically significant between-hospital variation. To measure the magnitude of variation between centers, a median odds ratio (MOR) was calculated. As described previously(23–25), the MOR represents the odds that two identical patients treated at different centers in a multicenter sample would undergo different therapies. An MOR greater than 1.2 is considered to be of clinically significant magnitude(26). The statistical significance of the MOR is measured with a conventional p-value.

Secondary outcomes of interest were 1) age at ASD closure and 2) total cost of ASD closure, and 3) hospital length-of-stay. In-hospital mortality was also another outcome of interest, but the total number of events was too low and made construction of multivariable models impossible. Association between date of procedure and secondary outcomes was assessed using similar generalized linear models with the same listed fixed and random effects. LOS and cost were modeled using log gamma distribution. For each model the canonical link was used. We hypothesized that the change in cost and LOS over the study period would be very different over the course of the study period for TC-ASD and O-ASD so separate models for each intervention were calculated.

Missing data were generally infrequent (<1% for most variables). However, there were >5% missing data for race. To mitigate bias, a separate categorical variable for “missing race” was generated. Otherwise cases with missing data were excluded by case restriction. No imputation was used.

All data analysis was performed using Stata MP 13 (Statacorp, College Station, TX). The threshold for statistical significance was p<0.05.

Results

Study population

From 1/1/2007 to 9/30/2015, a total of 6,585 subjects with ASD underwent closure at 47 centers across the United States contributing data to PHIS. Of this initial cohort, 8 centers performing 193 ASD closure procedures (141 TC-ASD and 52 O-ASD) did not meet our inclusion criteria. The resultant analytic cohort was composed of 6,392 closure cases of which 82% (5,262) were TC-ASD at 39 centers (Table 1). Median age for ASD closure was 6 years (IQR: 3–13). The population was 63% female and 64% white. Of the entire cohort, 5% had a known genetic syndrome.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population and procedural outcomes

| Transcatheter (5262= at 39 centers) | Operative (n=1130 at 39 centers) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at ASD closure (years) | 6 (IQR: 4–13) | 4 (IQR: 3–10) | 0.0001 |

| Female sex | 63% (3318) | 62% (700) | 0.48 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| White | 63% (3348) | 66% (746) | |

| Black | 8% (420) | 12% (135) | |

| Asian | 4% (189) | 4% (40) | |

| Other | 18% (941) | 14% (158) | |

| Missing | 7% (364) | 5% (51) | |

| Payer | <0.001 | ||

| Private insurance | 47% (2488) | 44% (492) | |

| Medicaid | 33% (1761) | 40% (447) | |

| Other government | 8% (410) | 5% (58) | |

| Other | 11% (603) | 12% (133) | |

| Known genetic syndrome | 5% (278) | 6% (68) | 0.98 |

| History of gastrointestinal condition | 2% (93) | 4% (46) | <0.001 |

| History of hematologic condition | 1% (60) | 2% (28) | <0.001 |

| History of neurological condition | 2% (104) | 3% (29) | 0.21 |

| History of pulmonary condition | 1% (48) | 3% (39) | <0.001 |

| History of other condition | 1% (58) | 2% (22) | 0.02 |

| OUTCOMES | |||

| Mortality | 0% (1) | 0.4% (5) | 0.001 |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 1 (IQR: 1-1) | 3 (IQR: 3–4) | 0.0001 |

| Total cost of hospitalization (2015$US) | 15981 (IQR: 12272 to 21053 | 27977 (IQR: 21208 to 34900) | 0.0001 |

Comparing TC-ASD and O-ASD cohorts, the TC-ASD cohort was older (p<0.0001), more likely to have private insurance (p<0.001), and less likely to have a history of gastrointestinal, hematologic, pulmonary, and miscellaneous medical conditions (all p<0.001).

One in-hospital death (0.0%, 95% CI: 0.0–0.2%) occurred following TC-ASD. The risk was significantly less than that following O-ASD (0.4%, 95% CI: 0.1–1.0%, p=0.001). Hospital length of stay was shorter after TC-ASD (median: 1 day, inter-quartile range: 1-1 day) than after O-ASD (median: 3 days, inter-quartile range: 3–4, p=0.0001). Median cost of hospitalization was also lower after TC-ASD (2015US$15,981, IQR: 12,272 to 21,053) than after O-ASD (2015US$27,977, IQR: 21,208–34,900, p=0.0001).

Observed trends in ASD closure

The annual rate of ASD closure procedures performed at study centers did not change over the study period. The total number of ASD closures (including both TC-ASD and O-ASD) across the 39 centers did not change significantly (−5.5 ASD per year, 95% CI: −25.9 to 14.8, p=0.53, Figure 1). This was also true of the number of TC-ASD (p=0.80) and O-ASD (p=0.43) procedures performed across the study sample. The number of ASD closure procedures per center also did not change significantly (−0.4 per year, 95% CI: −0.91 to 0.22, p=0.23, Figure 2), nor did the number of O-ASD or TC-ASD when considered separately. Over the same period, the total number of catheterization procedures performed in the study sample increased (559 cases per year, 95% CI: 417 to 701, p<0.001) while the total number of cardiac operations did not change significantly (47 cases per year, 95% CI: −65 to 158, p=0.34). In accordance with this, ASD cases represented a decreasing proportion of the total catheterizations performed both in the study sample (p=0.04) and by center (p=0.04), while there was no significant change in the proportion of total cardiac operations that ASD accounted for over both the entire study sample (p=0.34) or by center (p=0.57). The percentage of ASD closure cases performed per hospital varied (median 81%, range: 31–100%, IQR: 74–91%) (Figure 3).

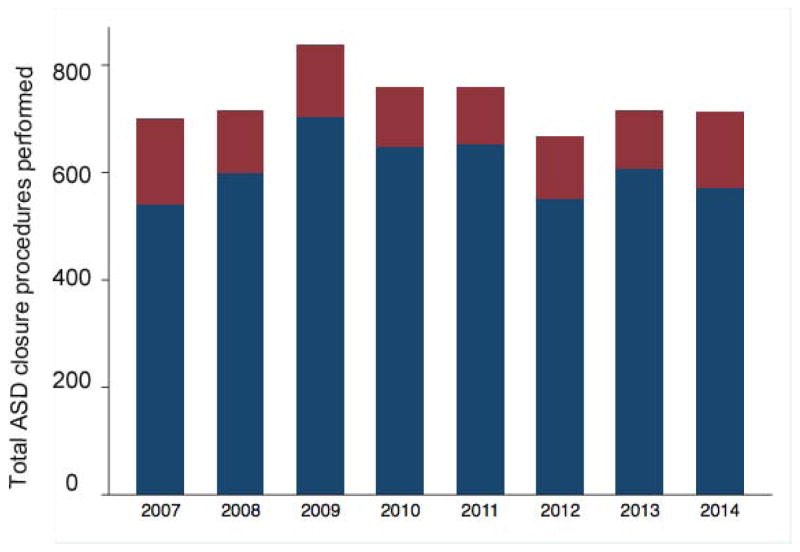

Figure 1. Total ASD closure cases from 2007–2014.

Bar graph depicting the total ASD closure procedures performed, as well as the number of operative ASD closure (maroon) and transcatheter device closure (navy blue) procedures. No significant change in the total number of ASD procedures (p=0.53), operative ASD procedures (p=0.43), or transcatheter device closure of ASD (p=0.8) was seen.

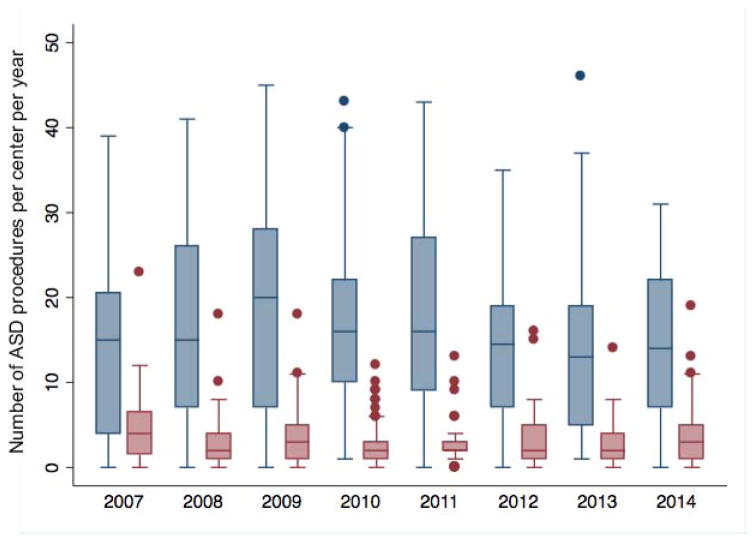

Figure 2. Number of ASD closure procedures per center 2007–2014.

Box and whiskers plot depicts the TC-ASD (navy) and O-ASD (maroon) procedures per year. The horizontal line marks the median number of procedures. Upper and lower limits of the box denote the 25th and 75th percentiles of the range. Whiskers are drawn to the adjacent value under the limit of 1.5 times the interquartile range. Values outside these limits (i.e. outliers) are marked with filled circles. There was no significant change in the number of ASD closure procedures per hospital (p=0.23). There was also no difference in the number of operative ASD (p=0.26) or transcatheter device ASD (p=0.40) closure procedures.

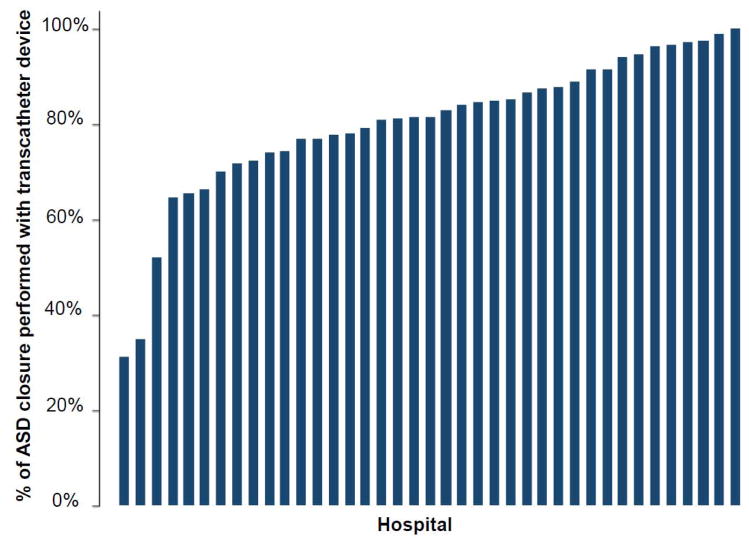

Figure 3. Observed proportion of ASD closure cases performed using transcatheter device 2007–2015.

Bar graph depicting the percentage of ASD closure cases performed using a transcatheter device (vs. operative closure) at each hospital in the study population between 2007 and 2015.

Trends in the decision to pursue O-ASD vs. TC-ASD

As described in the Methods section, a series of multivariate models measuring the propensity to pursue O-ASD vs. TC-ASD were calculated. The primary model proposed, including date of procedure as the primary exposure with an inflection point at 1/1/2013 is described in Table 2. Alternative models did not demonstrate superior fit (Supplementary Tables 1–4). In this model, the propensity to pursue O-ASD decreased (OR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.91–0.99, p=0.02) from 2007–2012. However, beginning in 2013 this trend reversed and the chance of performing O-ASD increased each year (OR: 1.21 95% CI: 1.06–1.39, p=0.006). Figure 4 depicts how the net probability of referral for O-ASD changed over the study period.

Table 2. Multivariable mixed effects model for choice between O-ASD and TC-ASD.

This table depicts the results of a single multivariate mixed effect model calculating the probability of choosing O-ASD over TC-ASD over the study period. Odds ratios greater than 1 represent a preference for O-ASD, and those less than 1 represent a preference for TC-ASD.

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Date of procedure (per year) | 0.95 | 0.91–0.99 | 0.02 |

| Date after 1/1/2013 (per year) | 1.21 | 1.06 to 1.39 | 0.006 |

| Subject age (per year) | 0.95 | 0.94–0.96 | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 0.95 | 0.82–1.10 | 0.52 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Black | 1.20 | 0.94–1.52 | 0.15 |

| Asian | 0.99 | 0.68–1.45 | 0.96 |

| Other | 0.82 | 0.66–1.03 | 0.09 |

| Missing/unknown | 0.93 | 0.66–1.31 | 0.68 |

| Payer | |||

| Private insurance | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 1.29 | 1.09–1.52 | 0.003 |

| Other government insurance | 0.98 | 0.70–1.37 | 0.90 |

| Other | 1.33 | 1.03–1.73 | 0.03 |

| Genetic syndrome | 0.93 | 0.69–1.26 | 0.64 |

| Gastrointestinal condition | 1.29 | 0.83–2.01 | 0.26 |

| Hematologic condition | 1.62 | 0.95–2.75 | 0.08 |

| Neurologic condition | 0.95 | 0.59–1.54 | 0.85 |

| Respiratory condition | 2.69 | 1.60–4.50 | <0.001 |

| Other medical condition | 1.53 | 0.84–2.8 | 0.17 |

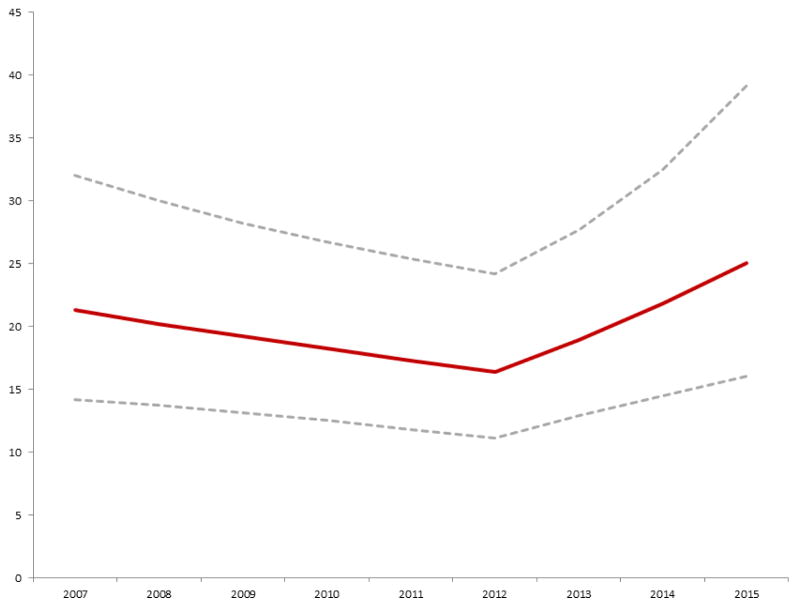

Figure 4. Probability of operative ASD closure versus transcatheter ASD closure.

Conditional standardization was used to calculate an adjusted probability of operative ASD closure vs. transcatheter device closure, for a hypothetical white male six year old boy with no co-morbid conditions (maroon line with 95% CI represented by the dashed grey lines). This was based on the mixed effects multivariate generalized linear model summarized in Table 2. The probability of operative ASD closure decreased significantly from 2007 until 2012 (OR: 0.95 per year, p=0.02). In 2013, there was a significant shift in probability favoring ASD (OR: 1.21 per year, p=0.006).

There was significant inter-hospital variation in the choice between O-ASD and TC-ASD even after adjusting for patient-level factors (likelihood ratio test p<0.001 and MOR: 2.79, 95% CI: 2.05–3.53, p<0.0001).

Other subject characteristics had strong associations with the decision to pursue O-ASD vs. TC-ASD. Increasing age (OR: 0.95, p<0.001) was associated with reduced probability of O-ASD, while history of a respiratory condition was associated with an increased probability of O-ASD (OR: 2.67, p<0.001).

Trends in age of ASD closure

A series of multivariate models assessing the association between date of closure and the age at closure were calculated. The model with the best fit included date of the procedure alone (Table 3, data for other models not shown). Over the study period, the age of closure decreased (−0.1 years of age/year, 95% CI: −0.2 to −0.004, p=0.04). There was significant inter-hospital variation in age of ASD closure (p<0.001). In the same model, O-ASD, genetic syndrome, and gastrointestinal condition were all associated with earlier ASD closure (p<0.001 for all).

Table 3. Multivariable mixed effects model of age at ASD closure.

This table depicts a single multivariate mixed effects model of age at closure of ASD adjusted for the listed covariates. Beta greater than zero demonstrate that there is an association with older age of ASD closure. Beta less than zero demonstrate an association with younger age at ASD closure.

| Beta | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Date of procedure (per year) | −0.1 | −0.2 to −0.004 | 0.04 |

| Surgical closure of ASD (vs. device closure) | −3.0 | −3.6 to −2.3 | <0.001 |

| Female sex | −0.5 | −1.0 to 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Black | −0.9 | −1.8 to 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Asian | −0.4 | −1.7 to 0.9 | 0.52 |

| Other | −0.9 | −1.6 to −0.2 | 0.01 |

| Missing/unknown | 0.4 | −0.7 to 1.5 | 0.46 |

| Payer | |||

| Private insurance | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Medicaid/CHIP | −2.5 | −3.1 to −1.9 | <0.001 |

| Other government insurance | 1.7 | 0.7 to 2.7 | 0.001 |

| Other | −0.6 | −1.5 to 0.3 | 0.16 |

| Genetic syndrome | −3.1 | −4.1 to −2.0 | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal condition | −3.3 | −5.0 to −1.5 | <0.001 |

| Hematologic condition | 1.8 | −0.3 to 3.9 | 0.09 |

| Neurologic condition | −1.4 | −3.1 to 0.3 | 0.11 |

| Respiratory condition | −1.6 | −3.9 to 0.6 | 0.14 |

| Other medical condition | 0.6 | −1.6 to 2.8 | 0.60 |

To determine if the association between the date of closure and subject age was different for O-ASD and TC-ASD, a secondary analysis calculating models restricted to either O-ASD or TC-ASD. In these models there were no significant associations between date of closure and subject age (p=0.43 and 0.86, other data not shown).

Trends in cost and length of stay

Trends in total hospital cost were measured by calculating mixed effects models separately for TC-ASD and O-ASD cohorts (Table 4a and 4b). Using conditional standardization, an “average” cost for each procedure can be calculated, adjusting for differences in patient characteristics between TC-ASD and O-ASD cohorts. The resultant adjusted total cost of TC-ASD was 2015US$20,045, compared to an estimated total cost of O-ASD of 2015US$25,608. Total cost of TC-ASD did not change significantly over the study period (p=0.21). The total cost of O-ASD increased over the study period (cost coefficient: 1.03 per year, p=0.002). For TC-ASD, gastrointestinal condition and respiratory condition were associated with increased total cost (p<0.001). For O-ASD, gastrointestinal, neurologic, respiratory, or other medical conditions were all associated with increased cost.

Table 4.

This table depicts two multivariate, mixed effects models for cost of a) transcatheter device closure of ASD and b) operative closure of ASD adjusted for the listed covariates. Coefficients greater than one demonstrate an association with higher cost, while those less than one demonstrate an association with lower cost.

| Table 4a. Multivariable mixed effects model TC-ASD cost | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI | p | |

| Date of procedure (per year) | 0.99 | 0.96–1.01 | 0.21 |

| Subject age (per year) | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 0.52 |

| Female sex | 1.00 | 0.96–1.05 | 0.91 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Black | 1.07 | 0.97–1.18 | 0.15 |

| Asian | 0.96 | 0.90–1.03 | 0.26 |

| Other | 0.98 | 0.92–1.04 | 0.44 |

| Missing/unknown | 1.02 | 0.92–1.14 | 0.67 |

| Payer | |||

| Private insurance | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 1.01 | 0.96–1.06 | 0.69 |

| Other government insurance | 1.07 | 0.95–1.20 | 0.24 |

| Other | 1.07 | 0.96–1.19 | 0.22 |

| Genetic syndrome | 1.06 | 0.95–1.19 | 0.29 |

| Gastrointestinal condition | 2.18 | 1.47–3.21 | <0.001 |

| Hematologic condition | 1.57 | 0.97–2.53 | 0.07 |

| Neurologic condition | 1.38 | 1.00–1.90 | 0.05 |

| Respiratory condition | 3.25 | 1.92–5.51 | <0.001 |

| Other medical condition | 1.74 | 1.04–2.92 | 0.03 |

| Table 4b. Multivariable mixed effects model O-ASD cost | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI | p | |

| Date of procedure (per year) | 1.03 | 1.01–1.04 | 0.002 |

| Subject age (per year) | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.07 |

| Female sex | 0.92 | 0.85–1.00 | 0.06 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Black | 1.32 | 1.04–1.69 | 0.02 |

| Asian | 0.78 | 0.64–0.94 | 0.01 |

| Other | 0.97 | 0.89–1.06 | 0.50 |

| Missing/unknown | 1.03 | 0.78–1.34 | 0.84 |

| Payer | |||

| Private insurance | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 1.14 | 1.03–1.26 | 0.009 |

| Other government insurance | 1.10 | 0.96–1.27 | 0.17 |

| Other | 1.27 | 1.06–1.51 | 0.008 |

| Genetic syndrome | 1.07 | 0.88–1.29 | 0.49 |

| Gastrointestinal condition | 1.63 | 1.01–2.65 | 0.047 |

| Hematologic condition | 1.60 | 0.97–2.65 | 0.06 |

| Neurologic condition | 1.83 | 1.37–2.45 | <0.001 |

| Respiratory condition | 2.85 | 1.84–4.40 | <0.001 |

| Other medical condition | 2.78 | 1.84–4.21 | <0.001 |

Trends in hospital length of stay were assessed by calculating mixed effects models separately for TC-ASD and O-ASD (Tables 5a and 5b). Estimated total LOS was 1.2 days after TC-ASD compared to 3.2 days after O-ASD. LOS after TC-ASD did not significantly change over the study period (p=0.47). For O-ASD, there was a non-significant trend towards increasing LOS over the study period (LOS coefficient: 1.03 per year, p=0.06). For TC-ASD, gastrointestinal condition and respiratory condition were associated with increased LOS (p<0.001). For O-ASD, gastrointestinal (p=0.005), hematologic (p=0.03), neurologic (p=0.046), respiratory (p<0.001), or other medical conditions (p<0.001) were all associated with increased LOS.

Table 5.

This table depicts two multivariate, mixed effects models for total hospital length of stay following a) transcatheter device closure of ASD and b) operative closure of ASD adjusted for the listed covariates. Coefficients greater than one demonstrate an association with longer length of stay, while those less than one demonstrate an association with shorter length of stay.

| Table 5a. Multivariable mixed model of hospital length of stay following TC-ASD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI | p | |

| Date of procedure (per year) | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.47 |

| Subject age (per year) | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.04 | 0.92–1.17 | 0.54 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Black | 1.28 | 1.04–1.57 | 0.02 |

| Asian | 0.94 | 0.79–1.12 | 0.52 |

| Other | 1.02 | 0.91–1.14 | 0.76 |

| Missing/unknown | 1.06 | 0.87–1.28 | 0.59 |

| Payer | |||

| Private insurance | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 1.02 | 0.90–1.15 | 0.75 |

| Other government insurance | 1.03 | 0.89–1.19 | 0.73 |

| Other | 1.21 | 1.03–1.43 | 0.02 |

| Genetic syndrome | 1.12 | 0.84–1.51 | 0.45 |

| Gastrointestinal condition | 4.29 | 2.48–7.42 | <0.001 |

| Hematologic condition | 1.67 | 0.88–3.15 | 0.12 |

| Neurologic condition | 1.99 | 1.20–3.31 | 0.008 |

| Respiratory condition | 3.98 | 2.23–7.00 | <0.001 |

| Other medical condition | 2.22 | 1.12–4.43 | 0.02 |

| Table 5a. Multivariable mixed model of hospital length of stay following O-ASD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI | P | |

| Date of procedure (per year) | 1.03 | 1.00–1.06 | 0.06 |

| Subject age (per year) | 1.00 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.54 |

| Female sex | 0.97 | 0.84–1.12 | 0.70 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Black | 1.68 | 1.24–2.29 | 0.001 |

| Asian | 0.87 | 0.72–1.05 | 0.14 |

| Other | 0.96 | 0.83–1.11 | 0.57 |

| Missing/unknown | 0.90 | 0.72–1.11 | 0.32 |

| Payer | |||

| Private insurance | 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 1.19 | 1.02–1.39 | 0.03 |

| Other government insurance | 1.14 | 0.95–1.38 | 0.16 |

| Other | 1.46 | 1.11–1.91 | 0.005 |

| Genetic syndrome | 1.21 | 0.95–1.53 | 0.12 |

| Gastrointestinal condition | 1.90 | 1.22–2.96 | 0.005 |

| Hematologic condition | 1.80 | 1.05–3.10 | 0.03 |

| Neurologic condition | 1.66 | 1.01–2.74 | 0.046 |

| Respiratory condition | 3.04 | 1.09–4.85 | <0.001 |

| Other medical condition | 3.94 | 2.28–6.82 | <0.001 |

Discussion

In this observational study of administrative data from 39 primary children’s hospitals in the United States, three major trends were observed. First, prior to 2013, the propensity to pursue TC-ASD increased. However, beginning in 2013 this trend reversed and the propensity to pursue O-ASD increased with each year, an inflection point temporally related to the change in the IFU for the ASO device. Second, the age of patients undergoing closure decreased progressively over the study period, suggesting that ASD closure (regardless of closure strategy chosen) is being pursued earlier. Third, cost of O-ASD increased significantly without a significant change in hospital length of stay, while no such changes were observed for TC-ASD cost or LOS.

Studies of trends in ASD closure using data from the National Inpatient Sample demonstrated that following introduction of the current generation of TC-ASD devices a marked increase in closure of ASD in adults (27,28), with a disproportionate increase in the TC-ASD relative to O-ASD(28). To our knowledge, no multicenter data has assessed trends in ASD closure in the contemporary era. Also, these previous studies are overwhelmingly in adult patients in whom larger patient size and smaller defect size generally result in a different calculus regarding ASD closure(29,30). The current study focuses on a contemporary study sample of primary pediatric hospitals. In the current study, assessing the raw numbers of TC-ASD and O-ASD procedures performed did not demonstrate significant changes in the preference between the two procedures over time, while in a mixed effects multivariable model there was a measurable shifts in preference between operative and transcatheter closure of ASD. Before 2013, there was a small but significant increase in the preference for TC-ASD, despite ongoing concern for device erosion following TC-ASD with ASO devices(9–13,31–33). From 2013 on, this trend reversed. This date was chosen to measure reaction to the 2012 FDA panel meeting and subsequent change in the IFU for the ASO(15–17). The modeling strategy used allowed us to compensate for changes in the number of hospitals contributing data over the study period, patient characteristics, and clustering of hospital behavior, all of which are potential sources of variation that are not accounted for in the analysis of raw data.

We acknowledge that in an observational study it is not possible to assert a causal relationship from the observed association. The behavior of groups of physicians is potentially influenced by numerous factors, and there may be alternative explanations for the observed trend not accounted for in our modeling strategy. While acknowledging these limitations, it is relevant to note that multiple alternative models were calculated to assess the association between date of procedure and ASD closure technique, which confirmed that the model showing an inflection between 2012 and 2013 had the best fit.

We also sought in this analysis to measure the amount of between-hospital variation in the choice between TC-ASD and O-ASD and found that there were large magnitude differences in practice between hospitals. This reflects significant practice variation, and represents a potential area where research and attention could improve quality of care for patients with ASD. We acknowledge that some clinically relevant data (e.g. ASD anatomy) are not available in an administrative database such as PHIS, which can result in unmeasured confounding. However, the distribution of these factors is unlikely to vary over thousands of cases and multiple hospitals, so we conclude that there continues to be tremendous variability in “real-world” practice of ASD closure.

These two observations suggest that at the individual hospital level there is uncertainty regarding the relative merits of O-ASD and TC-ASD, specifically the relative risks of each procedure. This may arise from uncertainty regarding the relative risks of each procedure. Device erosion is a potentially catastrophic consequence following TC-ASD and has rightfully garnered significant attention. Though quantifying its incidence has proved challenging, the current most conservative estimates of the risk of erosion appears to be 1 in 10009, 28, from which an unknown fraction develop life-threatening tamponade. The risk of procedure-associated death in isolated TC-ASD in published series are 0–0.15%(30,34,35). The best estimates of risk-adjusted procedural mortality following O-ASD, as derived from the Society for Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgeons Database, are between 3–9 per 1,000(5,36,37). Though there is risk standardization in these large series, care should be exercised in comparing outcomes between studies and the absolute risk of mortality with each procedure remains low. TC-ASD undeniably has other benefits over O-ASD, specifically shorter length of stay(5,36) and lower total cost relative to O-ASD(5,36), suggestive that in many cases TC-ASD represents better value than O-ASD.

The ramifications of these trends on patient outcomes and resource utilization cannot be assessed in the current study. Referring more patients for O-ASD will inevitably reduce the risk for erosion, but only results in a net reduction in harm to patients if the benefit exceeds the inherently higher risk of O-ASD. This can only be accomplished by identifying subgroup(s) of patients with a significantly higher risk of erosion than the overall population risk. To date, the single consistent risk factor for device erosion is deficient retro-aortic rim(10,38). However, deficient retro-aortic rim is extremely prevalent in pediatric patients (between 40–60%)(30,39–41), and it is not clear that the current definition of deficient retro-aortic rim discriminates the patients at highest risk of device erosion. There is recent evidence that patients with larger defects relative to body size and septal length and oversizing the device to the defect are more prevalent in erosions than in matched-controls(38). However, we must acknowledge that we have not yet been able to define a strata of patients in whom O-ASD is clearly favorable in terms of risk to TC-ASD. In this context, referral for O-ASD for patients who are not at increased risk of erosion potentially exposes them to increased risk of morbidity and increased cost without necessarily reducing the risk of mortality.

In our secondary analyses, we assessed whether age of ASD closure changed significantly over the study period, demonstrating that ASD closure (regardless of method of closure) was performed at increasingly younger age with each year. Though natural history studies demonstrate that patients with large ASD left untreated have dramatically reduced lifespan(42,43), to our knowledge, there is no evidence that early intervention produces dramatically different results in terms of any clinical outcome. There are multiple series that demonstrate that ASD can be closed in young patients(30,34,35,41), and conventional wisdom holds that closure of ASD surgically does not depend on patient size in a meaningful way. It is unclear what the impetus is for the trend towards progressively earlier intervention. This is especially surprising during the study period when attention on device erosion appears to have had a significant effect on practice. One might expect that emerging concern for a novel adverse outcome that cardiologists might have chosen to delay intervention and wait for data to guide their decision-making. However, the observed trend directly contradicts this, as both O-ASD and TC-ASD patients were performed progressively earlier over the study period. Secondary analysis studying this trend for O-ASD and TC-ASD separately did not demonstrate a significant association. Dividing the cohort reduces statistical power. Therefore, it is not possible for us to determine whether the observed trend is because of increasing comfort with TC-ASD in smaller patients or whether in the face of concern for device erosion some cardiologists are choosing to refer to patients for O-ASD and can do this at an earlier age. Regardless of motivation, this change in behavior may lead to unintended consequences. It is important to assess whether the rush towards “curing” a patient with an ASD exposes them to increased risk.

Cost and LOS are surrogates for morbidity, complexity of care, and resource utilization. Previous studies have demonstrated that TC-ASD has lower cost and shorter LOS than O-ASD(5,36). Over the study period, there were no significant changes in either following TC-ASD. However, total cost of O-ASD increased over the study period, and there was a non-significant trend towards an increase in LOS following O-ASD. This was unexpected. The approach to O-ASD has been consistent over the time period. As has been demonstrated in previous studies, the factors that result in a higher cost after operative procedures are primarily length of stay and adverse events (while transcatheter therapies are more expensive as a result of the cost of the device itself) (5,19,36). We expected that attention to these issues would have resulted in efforts to reduce post-operative length of stay. We acknowledge however, that it seems implausible that the results are the result of progressively worse surgical outcomes, and that they are the result of confounding by indication. For instance, it may be that TC-ASD patients are referred standard risk patients and that O-ASD is being reserved for higher-risk patients. Previous studies pooling patients over a similar time period and adjusting for these factors did not find this to be true(5,36), but they did not attend to changes in practice over that period.

An interesting question is whether the observed patterns of practice are likely to continue. It is possible that the trend favoring O-ASD will continue, but it seems more likely that the observed shift towards O-ASD is a temporary correction and that the proportion of O-ASD and TC-ASD patients will stabilize. However, new data or new technology might affect consensus and practice patterns. An observational post-market surveillance study of ASO device closure of ASD was performed with results not published to our knowledge at this time. The second version of the Improving Adult and Congenital Treatment (IMPACT®) Registry is seeking to track patients longitudinally following transcatheter interventions, including device closure of ASD. Though it is logistically challenging and expensive, follow-up data of this kind could inform changes in practice in either direction. Another possibility is that other devices may become available, which may change the perceived risk of erosion. The only device to date that has been implicated in a case of erosion is the ASO. During the study period in the US, only two alternative devices, the Gore Helex Septal Occluder and Gore Septal Occluder or Cardioform device. It would have been interesting to assess whether the use of either Gore device significantly affected the propensity to pursue TC-ASD. Unfortunately, though the Amplatzer devices can be identified in the PHIS database, neither Gore device, to our knowledge, is included in the devices coded in the database. Additionally, because of their design both devices have limited utility in large ASD. A third device from Gore designed to address larger ASD will begin enrolling patients in a clinical trial in 2017. Its introduction or the introduction of one of several devices currently in clinical use outside the United States, would potentially change the perceived risk of erosion and the propensity to refer for TC-ASD. In terms of O-ASD, to our knowledge, there have not been significant innovations in O-ASD that have reached broad practice. This is reflected in consistent clinical outcomes and LOS in our study. Minimally invasive operative closure of ASD promises reduced morbidity and length of stay, which may be more comparable to TC-ASD than previous operative strategies (44).

In the current study, we assessed how ASD closure practices changed at a study sample of pediatric hospitals over time. The motivations and thought process behind medical decision making is opaque in any retrospective study, and in this design it is not possible to evaluate it further. We acknowledge that concern for erosion certainly predated the FDA panel and change in IFU. We also acknowledged that there was likely a range of opinions and practices over time. The current study was designed to evaluate this. We created a series of alternative models to study how practice changed over time, (which are all included as Supplementary Tables). Taken as a whole these support that there is a nonlinear relationship in the probability of pursuing TC-ASD vs. O-ASD and that this is best modeled with the inflection point we used. Individual practitioners opinions about risk and their individual practice varied (as seen in the large magnitude inter-hospital variation in practice), but despite this variation there was a robust statistically significant trend towards increasing preference for O-ASD after the inflection point cited. We acknowledge that the dissemination of information and change in practice takes time and that the choice of a single cut point in time is inevitably arbitrary. However, on a population any error in the choice (i.e. having the cut point earlier or later than the true point where practice changed) biases the results towards the null. Therefore, concerns regarding the accuracy of the chosen date as a cut point reinforce the robustness of the demonstrated trend.

It is important in comparing choice between operative and transcatheter procedures over time to account for case-mix complexity. However, studying how case-mix complexity for ASD closure, specifically, changes over time is challenging. This is because different co-morbid medical conditions influence the risk of TC-ASD and O-ASD in a heterogeneous fashion. Some conditions (e.g. severe growth retardation or occlusion/thrombosis of the femoral veins) increase the technical complexity of TC-ASD more than O-ASD, while others (e.g. renal insufficiency or obesity) instead disproportionately increase the risk of cardiopulmonary bypass and postoperative recovery. Finally, there are some conditions that might have an unpredictable or variable effect on choice of TC-ASD vs. O-ASD. For example, a hypothetical patient with a history of prematurity and chronic lung disease might suffer greater respiratory compromise from an ASD. Their cardiologist might choose to pursue closure earlier, which (along with small patient size) might complicate TC-ASD. At the same time, an older patient with chronic lung disease might be a higher risk surgical patient (due to both pulmonary parenchymal disease and/or the presence of pulmonary hypertension), making TC-ASD preferable. Because of this assessment of individual factors would have to be performed over the study period and this results in large number of comparisons and risk for type I error. In deference to these concerns, we adjusted for known confounders in each model, which accounts for the contribution of each patient level factor individually on the propensity to pursue either closure strategy.

The present study has several other limitations. Administrative databases do not contain all clinically relevant covariates (e.g. ASD size and other anatomic information). Also, ICD-9 codes do not differentiate ostium secundum ASD from other types of ASD (e.g. sinus venosus type). These other subtypes are a minority of the total number of ASD and are not amenable to TC-ASD. Therefore they represent a small but unchanging proportion of the surgical case volume, and therefore are unlikely to influence the observed trends in practice. In the future, linkage of data from clinical registries and administrative databases could potentially be used to overcome these limitations, accessing the detailed clinical information in registries and cost and expedient longitudinal follow-up in administrative datasets. It should be noted that, in this case, linkage between an administrative database and both surgical (e.g. Society for Thoracic Surgery Congenital Heart Surgeons Database) and catheterization (e.g. IMProving Adult and Congenital Treatment®) databases would be necessary, potentially magnifying the logistical complexity of the task. Second, though it would be interesting to determine whether the observed trends were accompanied by changes in risk of major early adverse events or technical failure (including patients referred for TC-ASD in whom the practitioner chose not to release a device), this cannot be assessed well with administrative data. One single-center study hypothesized that concern for erosions resulted in their center in a higher risk of device embolization(45), but is limited by its small study population and the simultaneous introduction of the Helex Septal Occluder which in several studies has a significantly increased risk of device embolization(30,39). Third, PHIS is restricted to primary pediatric hospitals. These centers are the largest volume centers in the US and encompass a significant fraction of catheterizations performed nationally. However, ASD are treated in general hospitals and in smaller hospitals. Generalizing observed trends to these settings may introduce errors. Finally, though it is tempting to attribute the observed trends to specific causes is tempting, but we must acknowledge that in an observational study the ability to make these kinds of inferences is limited.

While acknowledging these limitations, we conclude that there is a significant shift away from transcatheter device closure of ASD after 2012 that followed changes in the IFU for the ASO device; and that there is tremendous between-hospital variation in choosing between transcatheter and operative closure of ASD. Practice variation of this kind represents an opportunity to improve the care of patients with ASD.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A retrospective observational study using administrative data from 39 primary pediatric hospitals was performed to study patterns of practice in closure of atrial septal defects (ASD) between 2007 and 2015.

Transcatheter device closure of ASD was the predominant method of treatment for ASD closure over this time.

Between 2007–2013, the average propensity to pursue TC-ASD increased, but after 2013 it decreased, coinciding with changes in the manufacturer’s Indications for Use for the Amplatzer Septal Occluder Device.

There was also large magnitude variability in the propensity to pursue transcatheter vs. operative ASD closure between hospitals.

Together these observations suggest that there continues to be uncertainty about which patients should be referred for TC-ASD or O-ASD.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Lanyu Mi MS from The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Center for Pediatric Clinical Effectiveness Healthcare Analytics Unit for her contributions querying the PHIS® Database.

Footnotes

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: Dr. O’Byrne receives research support from the National Institute of Health/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (K23 HL130420-01). The funding agencies had no role in the planning or execution of the study, nor did they edit the manuscript as presented. The manuscript represents the opinions of the authors alone. The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hoffman JIE, Kaplan S. The Incidence of Congenital Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002 May 30;39(12):1890–900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King TD, Thompson SL, Steiner C, Mills NL. Secundum atrial septal defect. Nonoperative closure during cardiac catheterization. JAMA. 1976 Jun 7;235(23):2506–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du ZD, Hijazi ZM, Kleinman CS, Silverman NH, Larntz K Amplatzer Investigators. Comparison between transcatheter and surgical closure of secundum atrial septal defect in children and adults: results of a multicenter nonrandomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002 Jun 5;39(11):1836–44. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01862-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosas M, Zabal C, Garcia-Montes J, Buendia A, Webb G, Attie F. Cong heart dis. 3. Vol. 2. Blackwell Publishing Inc; 2007. May, Transcatheter versus surgical closure of secundum atrial septal defect in adults: impact of age at intervention. A concurrent matched comparative study; pp. 148–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Byrne ML, Gillespie MJ, Shinohara RT, Dori Y, Rome JJ, Glatz AC. Cost comparison of transcatheter and operative closures of ostium secundum atrial septal defects. Am Heart J. 2015 May;169(5):727–735. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kutty S, Abu Hazeem A, Brown K, Danford CJ, Worley SE, Delaney JW, et al. Am J Cardiol. 9. Vol. 109. Elsevier Inc; 2012. May 1, Long-Term (5- to 20-Year) Outcomes After Transcatheter or Surgical Treatment of Hemodynamically Significant Isolated Secundum Atrial Septal Defect; pp. 1348–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butera G, Biondi-Zoccai G, Sangiorgi G, Abella R, Giamberti A, Bussadori C, et al. Percutaneous versus surgical closure of secundum atrial septal defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of currently available clinical evidence. EuroIntervention. 2011 Jul;7(3):377–85. doi: 10.4244/EIJV7I3A63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotowycz MA, Therrien J, Ionescu-Ittu R, Owens CG, Pilote L, Martucci G, et al. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 5. Vol. 6. Elsevier Inc; 2013. May 1, Long-Term Outcomes After Surgical Versus Transcatheter Closure of Atrial Septal Defects in Adults; pp. 497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amin Z, Hijazi ZM, Bass JL, Cheatham JP, Hellenbrand WE, Kleinman CS. Erosion of Amplatzer septal occluder device after closure of secundum atrial septal defects: Review of registry of complications and recommendations to minimize future risk. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent. 2004;63(4):496–502. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amin Z. Echocardiographic predictors of cardiac erosion after Amplatzer septal occluder placement. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014 Jan 1;83(1):84–92. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delaney JW, Li JS, Rhodes JF. Major Complications Associated with Transcatheter Atrial Septal Occluder Implantation: A Review of the Medical Literature and the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) Database. Cong heart dis. 2007 Jul 16;2:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2007.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crawford GB, Brindis RG, Krucoff MW, Mansalis BP, Carroll JD. Percutaneous atrial septal occluder devices and cardiac erosion: a review of the literature. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012 Aug 1;80(2):157–67. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diab K, Kenny D, Hijazi ZM. Erosions, erosions, and erosions! Device closure of atrial septal defects: How safe is safe? Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent. 2012 Jul 23;80(2):168–74. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore J, Hegde S, El-Said H, Beekman R, Benson L, Bergersen L, et al. Transcatheter device closure of atrial septal defects: a safety review. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013 May;6(5):433–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rare Serious Erosion Events Associated with St. Jude Amplatzer Atrial Septal Occluder (ASO) [Internet] United States Food and Drug Administration; 2013. [cited 2013 Nov 25]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/alertsandnotices/ucm371145.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amplatzer Septal Occluder and Delivery System: Instructions for Use. 2012:1–16. professional.sjm.com.

- 17.Mahapatra S, Graves AM. Letter to Physicians [Internet] professional.sjm.com. 2013:1–2. [cited 2013 Nov 25]Available from: http://professional.sjm.com/resources/product-performance/amplatzer-septal-occluder-performance/ifu-updates.

- 18.O’Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Shinohara RT, Jayaram N, Gillespie MJ, Dori Y, et al. Effect of center catheterization volume on risk of catastrophic adverse event after cardiac catheterization in children. Am Heart J. 2015 Jun;169(6):823–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Byrne ML, Gillespie MJ, Shinohara RT, Dori Y, Rome JJ, Glatz AC. Cost comparison of Transcatheter and Operative Pulmonary Valve Replacement (from the Pediatric Health Information Systems Database) Am J Cardiol. 2016 Jan 1;117(1):121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Mercer-Rosa L, Gillespie MJ, Dori Y, Goldmuntz E, et al. Trends in pulmonary valve replacement in children and adults with tetralogy of fallot. Am J Cardiol. 2015 Jan 1;115(1):118–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Hanna BD, Shinohara RT, Gillespie MJ, Dori Y, et al. Predictors of Catastrophic Adverse Outcomes in Children With Pulmonary Hypertension Undergoing Cardiac Catheterization: A Multi-Institutional Analysis From the Pediatric Health Information Systems Database. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Sep 15;66(11):1261–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feudtner C, Hays RM, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Neff JM. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsen K, Merlo J. Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on individual health: integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. AmJEpidemiol. 2005 Jan 1;161(1):81–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson PN, Chan PS, Spertus JA, Tang F, Jones PG, Ezekowitz JA, et al. Practice-level variation in use of recommended medications among outpatients with heart failure: Insights from the NCDR PINNACLE program. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2013 Nov;6(6):1132–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maddox TM, Chan PS, Spertus JA, Tang F, Jones P, Ho PM, et al. Variations in coronary artery disease secondary prevention prescriptions among outpatient cardiology practices: insights from the NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Feb 18;63(6):539–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hira RS, Kennedy K, Jneid H, Alam M, Basra SS, Petersen LA, et al. Frequency and practice-level variation in inappropriate and nonrecommended prasugrel prescribing: insights from the NCDR PINNACLE registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Jul 1;63(25 Pt A):2876–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh V, Badheka AO, Patel NJ, Chothani A, Mehta K, Arora S, et al. Influence of hospital volume on outcomes of Percutaneous Atrial Septal Defect and Patent Foramen Ovale closure: A 10-years US perspective. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014 Dec 22; doi: 10.1002/ccd.25794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karamlou T, Diggs BS, Ungerleider RM, McCrindle BW, Welke KF. The Rush to Atrial Septal Defect Closure: Is the Introduction of Percutaneous Closure Driving Utilization? Ann Thoracic Surg. 2008 Nov;86(5):1584–91. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butera G, Romagnoli E, Carminati M, Chessa M, Piazza L, Negura D, et al. Treatment of isolated secundum atrial septal defects: Impact of age and defect morphology in 1,013 consecutive patients. Am Heart J. 2008 Oct;156(4):706–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Byrne ML, Gillespie MJ, Kennedy KF, Dori Y, Rome JJ, Glatz AC. The influence of deficient retro-aortic rim on technical success and early adverse events following device closure of secundum atrial septal defects: An Analysis of the IMPACT Registry(®) Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017 Jan;89(1):102–11. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taggart NW, Dearani JA, Hagler DJ. Late erosion of an Amplatzer septal occluder device 6 years after placement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011 Jul;142(1):221–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DiBardino DJ, McElhinney DB, Kaza AK, Mayer JE., Jr Analysis of the US Food and Drug Administration Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience database for adverse events involving Amplatzer septal occluder devices and comparison with the Society of Thoracic Surgery congenital cardiac surgery database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009 Jun;137(6):1334–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiBardino DJ, Mayer JE., Jr Continued controversy regarding adverse events after Amplatzer septal device closure: Mass hysteria or tip of the iceberg? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011 Jul;142(1):222–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El-Said H, Hegde S, Foerster S, Hellenbrand W, Kreutzer J, Trucco SM, et al. Device therapy for atrial septal defects in a multicenter cohort: acute outcomes and adverse events. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Feb 1;85(2):227–33. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore JW, Vincent RN, Beekman RH, Benson L, Bergersen L, Holzer R, et al. Procedural results and safety of common interventional procedures in congenital heart disease: initial report from the national cardiovascular data registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Dec 16;64(23):2439–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ooi YK, Kelleman M, Ehrlich A, Glanville M, Porter A, Kim D, et al. Transcatheter Versus Surgical Closure of Atrial Septal Defects in Children: A Value Comparison. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Jan 11;9(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Brien SM, Clarke DR, Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Lacour-Gayet FG, Pizarro C, et al. An empirically based tool for analyzing mortality associated with congenital heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009 Nov;138(5):1139–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McElhinney DB, Quartermain MD, Kenny D, Alboliras E, Amin Z. Relative Risk Factors for Cardiac Erosion Following Transcatheter Closure of Atrial Septal Defects: A Case-Control Study. Circulation. 2016 May 3;133(18):1738–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Sunderji S, Mathew AE, Goldberg DJ, Dori Y, et al. Prevalence of Deficient Retro-Aortic Rim and Its Effects on Outcomes in Device Closure of Atrial Septal Defects. Pediatr Cardiol [Internet] 2014 May 14;35(7):1181–90. doi: 10.1007/s00246-014-0914-6. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00246-014-0914-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Goldberg DJ, Shinohara R, Dori Y, Rome JJ, et al. Accuracy of Transthoracic Echocardiography in Assessing Retro-aortic Rim prior to Device Closure of Atrial Septal Defects. Cong heart dis. 2014 Sep 16;:1–9. doi: 10.1111/chd.12226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petit CJ, Justino H, Pignatelli RH, Crystal MA, Payne WA, Ing FF. Percutaneous Atrial Septal Defect Closure in Infants and Toddlers: Predictors of Success. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012 Jul 18;34(2):220–5. doi: 10.1007/s00246-012-0413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Craig RJ, Selzer A. Natural History and Prognosis of Atrial Septal Defect. Circulation. 1968 May 1;37(5):805–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.37.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campbel M. Natural history of atrial septal defect. Br Heart J. 1970;32:820–6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.32.6.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bacha E, Kalfa D. Minimally invasive paediatric cardiac surgery. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014 Jan;11(1):24–34. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitchelson B, O’Donnell C, Ruygrok P, Wright J, Stirling J, Wilson N. Transcatheter closure of secundum atrial septal defects: has fear of device erosion altered outcomes? Cardiology in the Young. 2017 Jan 12;:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S1047951116002663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.