Abstract

Background

There is a growing trend for patients to seek the least invasive treatments with less risk of complications and downtime for facial rejuvenation. Thread embedding acupuncture has become popular as a minimally invasive treatment. However, there is little clinical evidence in the literature regarding its effects.

Methods

This single-arm, prospective, open-label study recruited participants who were women aged 40–59 years, with Glogau photoaging scale III–IV. Fourteen participants received thread embedding acupuncture one time and were measured before and after 1 week from the procedure. The primary outcome was a jowl to subnasale vertical distance. The secondary outcomes were facial wrinkle distances, global esthetic improvement scale, Alexiades–Armenakas laxity scale, and patient-oriented self-assessment scale.

Results

Fourteen participants underwent thread embedding acupuncture alone, and 12 participants revisited for follow-up outcome measures. For the primary outcome measure, both jowls were elevated in vertical height by 1.87 mm (left) and 1.43 mm (right). Distances of both melolabial and nasolabial folds showed significant improvement. In the Alexiades–Armenakas laxity scale, each evaluator evaluated for four and nine participants by 0.5 grades improved. In the global aesthetic improvement scale, improvement was graded as 1 and 2 in nine and five cases, respectively. The most common adverse events were mild bruising, swelling, and pain. However, adverse events occurred, although mostly minor and of short duration.

Conclusion

In this study, thread embedding acupuncture showed clinical potential for facial wrinkles and laxity. However, further large-scale trials with a controlled design and objective measurements are needed.

Keywords: polydioxanone, rejuvenation, rhytidoplasty, skin aging, thread embedding acupuncture

1. Introduction

Thread embedding acupuncture (TEA) is a type of acupuncture treatment utilizing an absorbable thread that is attached to a needle.1 After the acupuncture needle is inserted and removed, however, the thread is buried into human body to treat various disorders such as osteoporosis, constipation, and gastritis.2, 3, 4 Recently, TEA targeting under dermis became known to be effective for facial wrinkles and laxity; its practice has begun in clinics.5 TEA is similar to suture suspensions practiced in plastic surgery clinics; however, the procedure tools and methods are different. For several decades, there has been a growing trend for patients to pursue natural effects, to be reluctant for effects to be noticed upon immediate return to social and professional life, and also to prefer absorbable implants or materials. TEA is less invasive, and has short downtime and fewer side effects when compared with the surgical wrinkle removal sutures.6

There is little clinical evidence in the literature regarding the effects of TEA. In recent years, few retrospective chart reviews reported the effectiveness and safety of TEA for facial wrinkles and laxity using subjective satisfaction rating systems as primary outcomes.7, 8 We conducted a single-arm, prospective, open-label study to investigate the effect of TEA on facial wrinkles and laxity using a quantitative outcome.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics approval

This study was performed in accordance with the International Committee on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the revised version of the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong (KHNMC-OH-2014-09-007-002). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment, and participants were given ample time to decide about participating before signing the consent form.

2.2. Participant recruitment and inclusion/exclusion criteria

Participants were recruited by advertisements on bulletin boards at Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong. Included were individuals (1) who were women, (2) aged 40–59 years, (3) with Glogau photoaging scale III or IV,9 and (4) who agreed not to receive any other treatment during the study period. We excluded individuals who (1) were pregnant or breastfeeding; (2) had botulinum toxin, filler, or other implant injection within 6 months immediately prior to study entry; (3) had a keloidal or hypertrophic scar tendency; (4) had a history of herpes simplex; (5) had allergic skin disease; (6) were allergic to topical anesthetics or stainless needle; (7) had diabetes or tuberculosis; and (8) were taking anticoagulants or thrombolytic agents.

2.3. Sample size estimation

We wished to estimate the sample size that would be sufficient to detect significant differences in the “jowl to subnasale vertical distance” between before and after the procedure. Sample size was determined based on the results of a recent study.10 The mean difference and standard deviation of “jowl to subnasale vertical distance” before and after the procedure were 5.6 mm and 6.4 mm, respectively. Calculations were performed using 80% power, a 5% significance level, and a 10% dropout rate. The required sample size was approximately 14 participants:

C is a constant that depends on the values chosen for α and β, S is standard deviation of the variable, and D is difference.

2.4. Thread embedding acupuncture

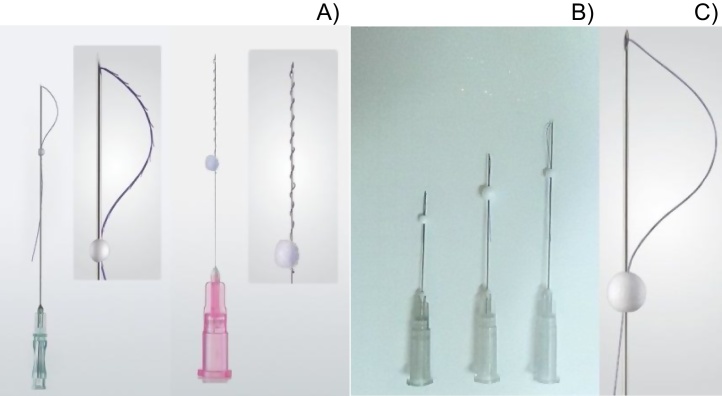

Cog-shaped TEA, screw-shaped TEA, and three different lengths of mono TEA (Miracu; DongBang Acupuncture Inc., Boryeong, Korea) were used in this study. Detailed specifications are described in Table 1, and different types of TEAs are presented in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Specification of thread embedding acupunctures used in this study.

| Thread |

Needle |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Shape | USP | Length (mm) | Gauge | Length (mm) |

| Polydioxanone | Bidirectional cogs | 4–0 | 110 | 23 | 60 |

| Screw | 5–0 | 70 | 27 | 50 | |

| Mono | 5–0 | 30 | 27 | 30 | |

| Mono | 5-0 | 50 | 27 | 40 | |

| Mono | 5-0 | 70 | 27 | 50 | |

USP, United State Pharmacopeia.

Fig. 1.

The shape of TEA.

(A) Bidirectional cog-shaped TEA. (B) Screw-shaped TEA. (C) Mono-shaped TEA.

TEA, thread embedding acupuncture.

2.5. TEA procedure

The procedure was performed on the left side first, and then it was performed in the same way on the right side. The procedure for the left side of face is described in this manuscript. TEA needles were inserted into the subcutaneous soft tissue layer, under the dermis, according to the lines shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4. After insertion of mono and screw TEA needles, removal of the needle alone results in the thread remaining intact in the tissue. After the insertion of bidirectional cog TEA needle, the threads out of the skin were gently pulled upward in the opposite direction of laxity, for the cogs to hold the soft tissues well. The thread ends are cut and pushed into the subcutaneous tissue.

Fig. 2.

Correcting jowls. (A). (B). (C).

TEA, thread embedding acupuncture.

Fig. 3.

Correcting nasolabial folds. (A). (B).

Fig. 4.

Correcting (A) mid and lower face sagging and (B) under eye sagging.

2.5.1. Preparation

EMLA cream (AstraZeneca, Alderley Park, Cheshire, UK) was applied on the whole face for 1 hour before the procedure. The procedure areas were covered with Betadine.

2.5.2. Correcting jowls

-

(1)

A mono TEA needle (length 5 cm) was inserted according to the straight line from acupuncture point ST5 to ST6. Relative to this line, three further TEAs were inserted in the same manner with the same 5 cm intervals, and then the needles were removed (Fig. 2-A).

-

(2)

A mono TEA needle (length 5 cm) was inserted according to the straight line from acupuncture point ST6 to ST7. Relative to this line, three further TEA needles were inserted in the same manner with inward 5 cm intervals, and then they were removed (Fig. 2-A).

-

(3)

A bidirectional cog TEA needle was inserted according to the straight line from acupuncture point ST6 to ST5. Relative to this line, three further bidirectional cog TEA needles were inserted in the same manner with 5 cm intervals. The threads out of the skin were gently pulled upward, and the thread ends were cut and pushed into the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 2-C).

-

(4)

A screw TEA needle was inserted according to the Marionette line (Fig. 2-B).

-

(5)

A mono TEA needle of length 4 cm was inserted from right to left around the CV23 (Fig. 2-B).

2.5.3. Correcting nasolabial folds

-

(1)

A screw TEA needle was inserted according to the nasolabial folds (Fig. 3-A).

-

(2)

A bidirectional cog TEA needle was inserted according to the straight line from 2 cm outward and 1 cm downward from eye to LI20. Relative to this line, three further bidirectional cog TEA needles were inserted in the same manner with 1 cm intervals lateral downward. The threads out of the skin were gently pulled upward, and the thread ends were cut and pushed into the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 3-A).

-

(3)

A mono TEA needle (length 5 cm) was inserted according to the straight line from LI20 to BL1, from 0.5 cm lateral downward of LI20 to ST2, from 1 cm lateral downward of LI20 to ST3, and from 1.5 cm lateral downward of LI20 to ST18 (Fig. 3-B).

2.5.4. Correcting mid and lower face sagging

Two mono TEA needles (length 5 cm) were inserted according to the straight line from ST6 to the direction of ST3 and ST2 continuously. Relative to this line, six further mono TEA needles (length 5 cm) were inserted in the same manner with 0.5–1 cm intervals lateral downward. Depending on the shape of the patient’s face’ (Fig. 4-A).

2.5.5. Correcting under eye sagging

-

(1)

Mono TEA needles (length 3 cm) were inserted according to the straight line from 0.5 cm below ST1 in the direction of the lateral angle of the eye (Fig. 4-B). Relative to this line, two more mono TEA needles (length 3 cm) were inserted at the left and right of the line, at 1 cm intervals.

-

(2)

Three mono TEA needles (length 3 cm) were inserted straight across ST1 at the bottom of the eye, across GB1 at the outer downward of the eye, and vertically in the direction of the lateral angle of the eye. Relative to this line, three more mono TEA needles (length 3 cm) were inserted in parallel (Fig. 4-B).

2.5.6. Postprocedure care

The procedure areas were covered with Betadine. To minimize edema and bruising, an ice pack was applied for 10 minutes. Within the first 2 weeks after the procedure, excessive or big movements of the perioral muscles such as yawning, laughing, singing, and chewing were prohibited, as was facial massage. Participants were encouraged to sleep in a supine position.

2.6. Outcome measurements

2.6.1. Primary outcome measurement

The change of jowl to subnasale vertical distance using Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator (Adobe Photoshop CS6, Adobe Illustrator CS6; Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA) was the primary outcome measurement. Standardized photographs were taken for the participants at baseline on the day before and 1 week after the procedure. Photographs of the face were taken using the DSLR camera EOS 350D (focus length 55 mm, shutter speed 1/80, f/5.6, ISO 1600; Kiss Digital N, Canon, Japan) in a state fit for vertical and horizontal alignment of the patient. The before and after photographs were overlapped using Photoshop and were arranged horizontally and vertically to align the position and size of the pupil and face by an independent Photoshop expert. Then, the change of jowl to subnasale vertical distance was calculated using Adobe Illustrator (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Primary outcome measurement. Marking the key points (A) before and (B) after the procedure. (C) Overlapping two pictures to determine picture size and the changes. Calculating distances between the points (D) before and (E) after the procedure.

2.6.2. Secondary outcome measurements

2.6.2.1. Changes of facial line distance

The changes of facial line distance were calculated in the same manner as a primary outcome measure. Infraeye lines, melolabial folds, nasolabial folds, and Marionette lines were calculated.

2.6.2.2. Alexiades–Armenakas laxity scale

Two independent doctors of Korean medicine evaluated patient’s laxity using the Alexiades–Armenakas laxity scale.11 It was calculated before and after the difference between the mean values of the two evaluators.

2.6.2.3. Global esthetic improvement scale

Overall appearance of the face was assessed using a global esthetic improvement scale by two independent doctors of Korean medicine.12

2.6.2.4. Patient-oriented self-assessment scale

Assessment of facial wrinkles and laxity was performed with a patient-oriented self-assessment scale with the same frequency as the primary measurements. Participants assessed their degrees using a 10 cm vertical line visual analog scale. The scale was marked at the top with “most severe condition,” with the bottom labeled as “fine condition.”

2.6.2.5. Safety assessment

Adverse events associated with TEA include swelling, ecchymosis, subjective feeling of tightness, pain, infection, dimpling, thread extrusion, and foreign body reactions.13 At the follow-up visit 1 week after the procedure, all adverse events were recorded in the case report forms.

2.6.3. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. A paired t test or Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to examine any significant difference in the values of jowl to subnasale vertical distance, other facial line distances, Alexiades–Armenakas laxity scale, and patient-oriented self-assessment scale before and after the procedure according to the results of normality assumption. For the global esthetic improvement scale, we described the distribution of the results. In all tests, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA); we used intention-to-treat and last-observation-carried-forward analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

All the 14 participants screened were eligible and enrolled for the study. The mean age was 53.78 years (range: 40–59 years), and all participants were Asian females with Glogau photoaging scale III (Fig. 4). All participants received TEA procedure; 12 of them revisited for the follow-up 1 week later and completed all outcome measurements. Two participants did not visit on the follow-up day; however, adverse events were investigated via a phone call.

3.2. Change of jowl to subnasale vertical distance

Prior to the procedure, values of the participants showed a normal distribution. Left and right jowl to subnasale vertical distances decreased 1.87 mm, and 1.43 mm, respectively; it is not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes of jowl to subnasale vertical distance.

| N = 14 | Before TEA | 1 wk after TEA | Mean difference | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left (mm) | 147.84 ± 12.05 | 145.97 ± 11.98 | 1.87 ± 7.44 | 0.364 |

| Right (mm) | 151.56 ± 11.25 | 150.13 ± 8.92 | 1.43 ± 7.48 | 0.487 |

Data are means ± SD, using paired-sample T test.

SD, standard deviation; TEA, thread embedding acupuncture.

3.3. Changes of facial line distance

Prior to the procedure, all values of the participants did not show normal distributions. Except for the right infraeye line, all mean distances of facial lines decreased; the changes of both melolabial folds and both nasolabial folds were statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes of facial lines and folds.

| N = 14 | Before TEA | 1 wk after TEA | Mean difference | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lt infraeye line (mm) | 86.88 ± 28.57 | 76.50 ± 23.81 | 10.37 ± 20.91 | –1.961 | 0.050 |

| Rt infraeye line (mm) | 73.51 ± 25.18 | 74.63 ± 17.04 | –1.12 ± 21.20 | –0.235 | 0.814 |

| Lt ML fold (mm) | 88.97 ± 52.89 | 71.89 ± 52.77 | 17.08 ± 33.87 | −2.666 | 0.008* |

| Rt ML fold (mm) | 75.10 ± 52.36 | 63.95 ± 44.98 | 11.15 ± 17.48 | –2.521 | 0.012* |

| Lt NL fold (mm) | 109.91 ± 30.85 | 101.77 ± 31.65 | 8.14 ± 10.64 | –2.981 | 0.003* |

| Rt NL fold (mm) | 94.74 ± 37.25 | 81.29 ± 35.52 | 13.45 ± 17.15 | –2.824 | 0.005* |

| Lt Marionette line (mm) | 18.82 ± 16.54 | 16.21 ± 15.03 | 2.61 ± 4.81 | –1.955 | 0.051 |

| Rt Marionette line (mm) | 14.00 ± 10.89 | 10.75 ± 6.95 | 3.25 ± 7.22 | –1.836 | 0.066 |

Data are means ± SD, using Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Lt, left; Rt, right; ML, melolabial; NL, nasolabial; SD, standard deviation; TEA, thread embedding acupuncture.

p < 0.05.

3.4. Alexiades–Armenakas laxity scale

Data are shown in Table 4. Four participants were evaluated to have improved by both the independent evaluators. Each evaluator evaluated as “improved” for four and nine participants by 0.5 grades, respectively.

Table 4.

Changes in the Alexiades–Armenakas laxity scale.

| N = 14 | Before TEA | 1 wk after TEA | Mean difference | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexiades–Armenakas laxity scale | 2.89 ± 0.21 | 2.63 ± 0.27 | 0.27 ± 0.27 | –2.72 | 0.007* |

Data are means ± SD, using Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

SD, standard deviation; TEA, thread embedding acupuncture.

p < 0.05.

3.5. Global aesthetic improvement scale

The evaluation results of the two evaluators were consistent (Fig. 6). Nine participants were evaluated to be “somewhat improved” (improvement of the appearance better compared with the initial condition, but a touch-up is advised), and five to be moderately improved (marked improvement of the appearance, but not completely optimal).

Fig. 6.

Result of the global aesthetic improvement scale.

3.6. Patient-oriented self-assessment scale

Data are shown in Table 5. Both laxity and wrinkle scale values decreased significantly.

Table 5.

Changes of self-assessment of facial wrinkles and laxity (vas).

| N = 14 | Before TEA | 1 wk after TEA | Mean difference | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facial laxity | 5.86 ± 1.46 | 4.00 ± 2.04 | 1.86 ± 1.23 | –3.220 | 0.001* |

| Facial wrinkles | 5.79 ± 2.15 | 4.07 ± 1.98 | 1.71 ± 1.33 | –3.269 | 0.001* |

3.7. Safety assessment

On the follow-up visit a week post procedure, postprocedural complications seen in these participants were minor: swelling, ecchymosis, and pain. Mild ecchymosis occurred in four of the 14 participants, and a wide range of ecchymosis occurred in three. Swelling and pain lasted until a week after the procedure in two participants; however, the severe condition disappeared 3–4 days after the procedure. Infection, dimpling, thread extrusion, and foreign body reactions were not seen in any of the participants.

4. Discussion

Interest in cosmetic procedure for facial wrinkles and laxity in Korea is very high; and preference for noninvasive, short-recovery-time procedures has also increased lately. The aging process affects the skin and underlying tissues through intrinsic and extrinsic factors. With aging, thinning of the epidermis and subcutaneous fat layers occurs; progressive loss of organization of elastic fibers and collagen also occurs. These changes contribute to wrinkles and laxity of the face.14

TEA is another type of acupuncture treatment utilizing an absorbable thread that is attached to a needle.1 The TEA procedure is similar to subdermal suture suspension, which uses nonabsorbable polymer15; however, unlike suture suspension, TEA uses absorbable and relatively fine, short threads and needles. In addition, the TEA procedure does not need to make a suture or long incision. In mono TEA, only the needles need to be extracted, and in cog TEA, the threads need to be pulled gently and the thread out of the skin to be cut; both types of TEA do not need to make an anchorage or sutures. These unique properties result in fewer scars, a low incidence of complication, and a short recovery time.

Recently, TEA targeting under the dermis became known to be effective for facial wrinkles and laxity and its practice has begun in clinics.5 The material of TEA thread is polydioxanone, which is a synthetic monofilamentous polymer made of polyester or a polymer of polydioxanone. It retains 50% tensile strength after 4 weeks, takes 180 days to be absorbed, and also has low tissue reactivity.16 Mechanisms of how TEA improves facial wrinkles and laxity are explained by two factors: tensile strength of threads, and tissue reaction around the implanted thread. In an in vivo study, longer, thicker mono or cog threads have more tensile strength, and thicker myofibroblast formation was observed around the cog thread than around the mono thread.17, 18

According to an article that analyzed trends in academic research based on TEA, a total of 100 clinical trials used TEA until April 2016. Of these, 55 were case studies, 39 were randomized controlled studies, and six were case control studies. These studies explored the effects of TEA on internal diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, facial paralysis, and gynecological diseases.19 Only seven cases related to facial cosmetics have been reported in Korea. To the best of our knowledge, no other form of research has been reported in other countries, including Korea.

Various types of threads with special design have been introduced; however, no studies reported using TEA for facial wrinkles and laxity with a prospective design. Previous studies on the effect of using similar thread-lifting procedures are sparse. There were two retrospective chart reviews of barbed thread.7, 8 In addition, none have used quantitative and objective measurements or validated observer-rated esthetic scores.

In this study, in order to lift nasolabial fold, melolabial fold, and lower jaw region, 4-0 USP cog threads and 5-0 USP screw threads were used, whereas 5-0 USP mono TEA was used to improve laxity around the eye according to the method introduced earlier in a previous study.6 In order to solve the difficulty of reproducibility, which is one of the problems of research for confirming the effect of cosmetic procedure, it was presented as figures of the procedure. In addition, in order to evaluate the results quantitatively, standardized photographs were taken before and after the procedure; two pictures were overlapped after the size and position were adjusted and the changes in wrinkles and folds were measured in this prospective study.

The Asian females with Glogau photoaging scale III, mean age 53.78 years, received one-time TEA procedure, and after a week of the procedure, left and right jowl to subnasale vertical distances decreased by 1.87 mm and 1.43 mm, respectively; however, the decrease is not statistically significant. Among the measured lines, changes of both melolabial and nasolabial folds were most evident (17.08 mm, 11.15 mm, 8.14 mm, and 13.45 mm, respectively). The results of the Alexiades–Armenakas laxity scale and global esthetic improvement scale after one-time TEA procedure show that better results could be obtained if additional correction procedure was done. Participants’ winkles and laxity improved significantly. Ecchymosis, edema, and mild pain occurred up to a week after the procedure; however, infection, dimpling, thread extrusion, and foreign body reactions were not seen in all the participants.

On the basis of these results, TEA procedure of this study is relatively effective and safe for improving mid face laxity represented by melolabial and nasolabial folds. Otherwise, no signification effect was observed on the primary outcome of the study. We selected the change of jowl to subnasale vertical distance as a primary outcome on the basis of a previous study that evaluated the effect of face lift surgery.10 Unlike face lift surgery, TEA procedure used in this study was not enough to improve the laxity of lower jowl region. These differences are thought to be derived from the length, thickness, and shape of the thread and also depend on the use of an anchorage or sutures.

Limitations of this study are as follows. First, without individualized procedures in accordance with the type and state of face wrinkles and laxity, all participants underwent the procedure in the same manner, and it is thought to have influenced the results. Second, there is a limit to the outcome measurement which is obtained by overlapping two pictures taken at different points in time. Since there are few quantitative, reliable, or validated outcome measurements up to now, many similar studies still use a subjective scoring system or pictures of the patients. However, there are ethical concerns regarding using pictures of participants in research, especially comparative research of cosmetic procedures. It is impossible to take a picture to which will make the person unidentifiable, but which at the same time can be evaluated for wrinkles and degrees of laxity. It is difficult to quantify the changes due to the procedure by posting pictures before and after the procedure. Development of a quantitative evaluation method will enable a comparative study of various cosmetic procedures, and not only accumulate the evidence of the procedure. Third, in the present study, we compared the results before and after the one-time procedure. However, in clinical practice in Korea, TEA procedure is conducted two to three times with 2-week intervals, according to the condition of the patients. Therefore, in order to evaluate the actual result that is close to clinical practice, it is necessary to conduct further study with TEA procedure that is conducted two or more times. In addition, it seems necessary to use thicker, longer mono or cog threads for the elevation of the soft tissue of lower face. It may be necessary in the future, based on the result of present study, to study how many procedures are needed to show better improvement with a revised procedure technique. In this study, a long period of observation was not followed. Since the period of the absorption of polydioxanone is about 6–7 months, and in vivo studies showed that collagen content gradually increases over time after implantation of the thread,18 it seemed likely to produce more positive results in a long-term follow-up observation.

Nevertheless, this study is the first prospective clinical study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of TEA procedure on wrinkles and laxity using quantitative and objective measurements. The results of the present study could be used as the basis for further studies with a revised procedure or materials, an increased number of procedure, or a long-term follow-up observation.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Shin H.J., Lee D.J., Kwon K., Seo H.S., Jeong H.S., Lee J.Y. The success of thread-embedding therapy in generating hair re-growth in mice points to its possibly having a similar effect in humans. J Pharmacopuncture. 2015;18:20–25. doi: 10.3831/KPI.2015.18.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu B.X., Huang C.J., Liang D.B. Clinical control study on postmenopausal osteoporosis treated with embedding thread according to syndrome differentiation and medication. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2011;31:1349–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li D.B., Tan J.F., Miao C.H. Treatment of constipation by intensive acupoints thread embedding combined with local anal operation. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2009;29:260–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li H., Tang C.Z., Li S.H., Zhang Z., Chen S.J., Zhang J.W. Effects of thread embedding therapy on nucleotides and gastrointestinal hormones in the patient of chronic gastritis. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2005;25:301–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Y.J., Kim H.N., Shin M.S., Choi B.T. Thread embedding acupuncture inhibits ultraviolet B irradiation-induced skin photoaging in hairless mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/539172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yun Younghee, Kim Tae-Yeol, Lim Tae-Jung, Hwang Yong-Ho, Choi In-Hwa. Narrative review and propose of thread embedding acupuncture procedure for facial wrinkles and facial laxity. J Korean Med Ophthalmol Otolaryngol Dermatol. 2015;82:119–133. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suh D.H., Jang H.W., Lee S.J., Lee W.S., Ryu H.J. Outcomes of polydioxanone knotless thread lifting for facial rejuvenation. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:720–725. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park T.H., Seo S.W., Whang K.W. Facial rejuvenation with fine-barbed threads: the simple Miz lift. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:69–74. doi: 10.1007/s00266-013-0177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glogau R.G. Aesthetic and anatomic analysis of the aging skin. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1996;15:134–138. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones B.M., Lo S.J. How long does a face lift last? Objective and subjective measurements over a 5-year period. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:1317–1327. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31826d9f7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexiades-Armenakas M. A quantitative and comprehensive grading scale for rhytides, laxity, and photoaging. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:808–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narins R.S., Brandt F., Leyden J., Lorenc Z.P., Rubin M., Smith S. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of Restylane versus Zyplast for the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:588–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rachel J.D., Lack E.B., Larson B. Incidence of complications and early recurrence in 29 patients after facial rejuvenation with barbed suture lifting. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman O. Changes associated with the aging face. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2005;13:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulamanidze M.A., Fournier P.F., Paikidze T.G., Sulamanidze G.M. Removal of facial soft tissue ptosis with special threads. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:367–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tajirian A.L., Goldberg D.J. A review of sutures and other skin closure materials. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:296–302. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2010.538413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang H.J., Lee W.S., Hwang K., Park J.H., Kim D.J. Effect of cog threads under rat skin. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1639–1643. doi: 10.2310/6350.2005.31301. discussion 1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurita M., Matsumoto D., Kato H., Araki J., Higashino T., Fujino T. Tissue reactions to cog structure and pure gold in lifting threads: a histological study in rats. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31:347–351. doi: 10.1177/1090820X11398474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee Y.S., Han C.H., Lee Y.J. A literature review on the study of thread embedding acupuncture in domestic and foreign journals—focus on clinical trials. J Soc Prevent Korean Med. 2016;20:93–113. [Google Scholar]