Abstract

Background

To establish and validate diagnostic criteria for adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP) due to colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) mutation.

Methods

We developed diagnostic criteria for ALSP based on a recent analysis of the clinical characteristics of ALSP. These criteria provide “probable” and “possible” designations for patients who do not have a genetic diagnosis. To verify its sensitivity and specificity, we retrospectively applied our criteria to 83 ALSP cases who had CSF1R mutations (24 of these were analyzed at our institutions, and the others were identified from the literature), 53 cases who had CSF1R mutation-negative leukoencephalopathies, and 32 cases who had cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) with NOTCH3 mutations.

Results

Among the CSF1R mutation-positive cases, 50 cases (60%) were diagnosed as “probable” and 32 (39%) were diagnosed as “possible,” leading to a sensitivity of 99% if calculated as a ratio of the combined number of cases who fulfilled “probable” or “possible” to the total number of cases. With regard to specificity, 22 cases (42%) with mutation-negative leukoencephalopathies and 28 (88%) with CADASIL were correctly excluded using these criteria.

Conclusions

These diagnostic criteria are very sensitive for diagnosing ALSP with sufficient specificity for differentiating from CADASIL and moderate specificity for other leukoencephalopathies. Our results suggest that these criteria are useful for the clinical diagnosis of ALSP.

Keywords: Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP), hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS), pigmented orthochromatic leukodystrophy (POLD), colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R), alanyl-transfer (t)RNA synthetase 2 (AARS2), leukoencephalopathy, diagnostic criteria

INTRODUCTION

The differential diagnosis of leukoencephalopathy is extensive [1, 2]. Specialized investigations such as biochemical, genetic, or neuropathologic analyses are required for an accurate diagnosis. Due to recent advances in molecular genetics, genetic tests play an important role in the diagnosis of some leukoencephalopathies [1]. To perform genetic tests efficiently, it is important to understand the characteristic clinical features of a disease and establish useful diagnostic criteria.

Since the discovery of colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) as a causative gene for hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) [3] and more recently for pigmented orthochromatic leukodystrophy (POLD) [4], more than 120 cases with CSF1R mutations have been reported worldwide but it has been relatively more common in Japan compared to other countries [5]. HDLS and POLD cases, carriers of CSF1R mutations are characterized as having “adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia” (ALSP) [4]. Interestingly, CSF1R mutations are not always found in pathologically-confirmed HDLS cases [6]. Mutations in other genes appear to be responsible in cases of HDLS that are negative for CSF1R mutations. Indeed, mutations in alanyl-transfer (t)RNA synthetase 2 (AARS2) have been recently identified in 5 cases who were suspected to have ALSP, but were negative for CSF1R mutation [7].

Recently, we have clarified clinical characteristics of ALSP by analyzing 122 cases with CSF1R mutations [5]. Based on these findings, we propose diagnostic criteria for ALSP due to CSF1R mutation and attempt to validate them.

METHODS

Establishing diagnostic criteria

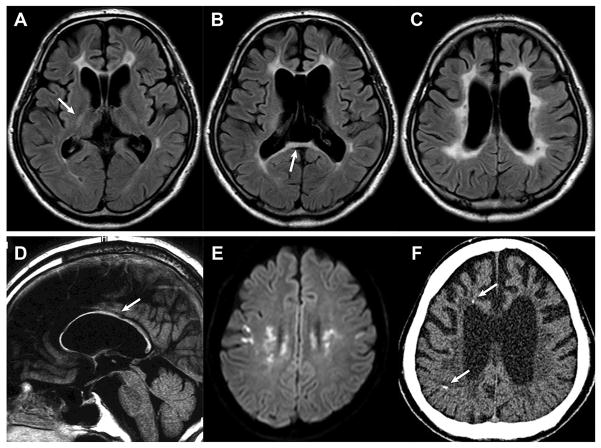

To establish diagnostic criteria, a working group was organized, consisting of board-certified neurologists from 5 institutions (Mayo Clinic, Niigata University, Shinshu University School of Medicine, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, and Tokushima University Graduate School) who have observed patients with ALSP. The diagnostic criteria were created based on the clinical characteristics obtained from our case series and review of the literature and further discussions among the study working group [5]. We defined 5 core diagnostic features (Table 1). Three exclusionary findings were added to increase diagnostic specificity. Patients who had 3 of the 5 core features (Table 1, criteria 2, 3, and 4a) and had a CSF1R mutation were classified as definitely having ALSP or “definite.” Patients who did not have results from genetic testing were identified to have “probable” or “possible” ALSP. The “probable” criteria also requires that the patients have all 5 core features identified in Table 1, but the “possible” criteria requires that only 3 are fulfilled (criteria 2a, 3, and 4a), with the aim of preventing false-negative diagnoses and missed opportunities for the genetic testing of those who lacked typical clinical features. Although not directly used to determine the diagnosis, we added 4 supportive findings to assist clinicians in making a diagnosis. Figure 1 shows the characteristic brain CT/MRI findings of ALSP, and Table 2 provides additional comments on the diagnostic criteria.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for ALSP

Core features

| |

|

| |

| Diagnosis by the criteria | |

| Definite: Fulfill core features 2, 3, and 4a and confirmation of CSF1R mutation | |

| Probable: Fulfill core features 1–5, but genetic tests have not been performed | |

| Possible: Fulfill core features 2a, 3, and 4a, but genetic tests have not been performed | |

ALSP, Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia; CSF1R, colony stimulating factor 1 receptor; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Figure 1. Characteristic brain MRI/CT findings in patients with ALSP.

(A–E, MRI; F, CT) Fluid attenuated inversion recovery imaging of a 43-year-old case with p.Ile794Thr mutation in CSF1R (A–C, axial; D, sagittal). Abnormal signals are observed in frontal white matter around anterior horn of the lateral ventricles, in the posterior limb of the internal capsule (arrow, A), and in the splenium of the corpus callosum (arrow, B). A thinning of the corpus callosum is shown (arrow, D). (E) Diffusion-restricted lesions in a 22-year-old case with the splice site mutation (c.2442+1G>A) in CSF1R. (F) Calcifications are revealed by thin-slice CT of the 43-year-old case with p.Ile794Thr mutation (arrows). ALSP, Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia; CSF1R, colony stimulating factor 1 receptor; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Table 2.

Additional Comments on Diagnostic Criteria

| 1. Age at onset |

| The mean age at onset of ALSP was 43 ± 11 years (range, 18–78), but was significantly younger in women than in men (40 vs. 47 years) [5]. Ninety-five percent of the cases develop their disease by age 60 years [5]. |

| 2. Clinical signs and symptoms |

| Cognitive impairment or psychiatric symptoms are cardinal features and are seen with high frequency. Psychiatric symptoms include anxiety, depression, apathy, indifference, abulia, irritability, disinhibition, distraction, and other behavioral and personality changes. Pyramidal signs include hyperreflexia, spasticity, increased tone in extremities, and pseudobulbar palsy. Parkinsonism includes resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. Parkinsonian symptoms are not responsive to levodopa (6). Seizure is observed in approximately 30% of cases [5], but it may characterize ALSP from other leukoencephalopathies. |

| 3. Mode of inheritance |

| Sporadic cases are not uncommon. De novo mutations have been reported [5]. |

| 4. Brain CT/MRI findings |

| On brain MRI scans, the white matter lesions without gadolinium enhancement can be scattered and asymmetric during the initial stages of the disease but later become confluent, diffuse, and more symmetric. Frontal and parietal lobe predominance is observed with involvement of the periventricular deep white matter and dilation of the lateral ventricles. Thinning of the corpus callosum with signal abnormalities is observed even in the early stages of the disease [9, 11]. Fluid attenuated inversion recovery sagittal imaging is recommended to evaluate changes in the corpus callosum. Abnormal signaling in the pyramidal tracts and diffusion-restricted lesions are observed in some cases [5, 11]. None of ALSP cases showed middle cerebellar peduncle lesions, which are known as a characteristic finding of some leukoencephalopathies. |

| On brain CT scans, calcifications are often observed bilaterally in the frontal white matter adjacent to the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle and the subcortical region of the parietal lobe. Calcifications can be very small. Thus, thin-slice CT (1 mm) is recommended to detect those [5, 11]. Characteristic “stepping stone appearance” can be seen on sagittal view [10]. |

| 5. Neuropathologic findings |

| Neuropathologic findings include prominent white matter lesions with myelin and axon damages, neuroaxonal swelling (spheroid formation), and pigmented macrophage and glia [4]. |

| 6. CSF1R mutation |

| All reported mutations were located within the tyrosine kinase domain of CSF1R except for 2 frameshift mutations [5]. |

ALSP, Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia; CSF1R, colony stimulating factor 1 receptor; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Validation of the diagnostic criteria

We used CSF1R mutation-positive cases to determine the sensitivity of our criteria. First, we applied the criteria to 26 ALSP cases who were seen by us and 96 cases previously identified in the literature [5]. Next, we applied them to 67 cases with CSF1R mutation-negative leukoencephalopathies to test the specificity of the criteria. These cases were suspected to have ALSP with at least white matter abnormalities on brain MRI and referred to our institutions for genetic test for CSF1R mutation. The primary causes of the mutation-negative leukoencephalopathies were unknown. We also applied them to 40 cases with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) who had NOTCH3 mutations because CADASIL is 1 of the main differential diseases of ALSP [3].

Cases diagnosed as “probable” met all 5 core features; however, in this retrospective study, the exclusion of other diseases, 1 of the core features, was not always taken into account because we could not determine whether enough assessment for a differential diagnosis had been conducted in every case. All genetic analyses were approved by the institutional review board of each of the 5 institutions listed above. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

RESULTS

Among the ALSP cases with CSF1R mutations, 2 of 26 cases in our cohort and 37 of 96 cases from the literature were excluded due to a lack of information, including insufficient brain imaging or hereditary data. The number of cases fulfilling each designation is shown in Table 3. If we calculated the diagnostic sensitivity as a ratio of the number of cases diagnosed as “probable” or “possible” to the total number of cases, the sensitivity was 96% for our cohort and 99% when combined with the literature review cases.

Table 3.

Validation of the Diagnostic Criteria for Clinical Diagnosis of ALSP

| Number of Cases | Probable, n (%) | Possible, n (%) | Not Fulfilled, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivitya (%) | |||||

| Our case series | 24 | 20 (83) | 3 (13) | 1 (4) | 96 |

| Literature search | 59 | 30 (51) | 29 (49) | 0 (0) | 100 |

| Total | 83 | 50 (60) | 32 (39) | 1 (1) | 99 |

|

| |||||

| Specificity (%) | |||||

| Leukoencephalopathy without CSF1R mutation | 53 | 4 (8) | 27 (51) | 22 (42) | 42 |

| CADASIL with NOTCH3 mutation | 32 | 0 (0) | 4 (12) | 28 (88) | 88 |

ALSP, Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia; CADASIL, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy; CSF1R, colony stimulating factor 1 receptor

Sensitivity was calculated as a ratio of the number of cases who were diagnosed as probable or possible to the total number of cases.

Fourteen of 67 cases with mutation-negative leukoencephalopathies and 8 of 40 CADASIL cases were excluded due to missing information necessary for our evaluation. For diagnostic specificity, 22 (42%) and 28 (88%) cases did not meet either the “probable” or “possible” criteria, respectively (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In the process of establishing diagnostic criteria, we placed a greater weight on sensitivity than specificity because a substantial number of cases with ALSP are underdiagnosed. This retrospective validation of these diagnostic criteria showed that they had high sensitivity (≥96%). There was almost no possibility that cases with ALSP were missed when we used these criteria. We had only 1 ALSP case who did not fit the criteria [8]. This case initially presented with gait abnormalities, and was cognitively normal in the early stages of disease when the criteria were applied. However, cognitive impairment subsequently appeared, and the patient was classified as “probable” at that time. Although cognitive impairment is inevitable in ALSP, it should be noted that it can be inconspicuous during the initial disease stages.

Thinning of the corpus callosum is characteristic to ALSP [9]; thus, we included it in a parameter of “probable.” Of the 29 cases from the literature that fulfilled the “possible” criteria, information about the corpus callosum was not obtained in 17 cases. It is estimated that more cases would have been diagnosed as “probable” if their corpus callosum had been evaluated. A majority of cases with mutation-negative leukoencephalopathy were diagnosed as “possible,” but 4 cases met the “probable” criteria, suggesting that the thinning of the corpus callosum is characteristic, but is not specific to ALSP. We assumed that brain calcifications have high sensitivity and specific diagnostic power [10, 11]; however, we could not sufficiently validate this finding due to insufficient information in the literature. Thus, we did not include it in the core features, but in the supportive findings.

When the criteria were applied to the cases who had CSF1R mutation-negative leukoencephalopathies or CADASIL with NOTCH3 mutations, the specificity was 42% and 88%, respectively. We considered that the relatively low specificity for mutation-negative leukoencephalopathies was due to the minimum requirements set for the “possible” designation, which were in place to avoid missing atypical cases of ALSP. For yielding higher specificity, the brain imaging characteristics listed in Table 2 including the distribution pattern of the white matter lesions and the brain calcifications may be beneficial. On the other hand, these criteria could successfully be used to differentiate CADASIL from ALSP. Cerebral infarction cases frequently present with diffusion-restricted lesions on brain MRI that are occasionally observed in ALSP cases as well (Figure 1E); therefore, hereditary cerebral small vessel diseases including CADASIL are part of the differential diagnoses of ALSP. One of the exclusion criteria, “stroke-like episodes more than twice,” was helpful for excluding CADASIL because there were no ALSP cases who had 2 or more stroke-like episodes. We showed additional useful points for differentiating ALSP from other leukoencephalopathies in Supplementary Table 1.

Patients with leukoencephalopathy due to AARS2 mutations, termed as AARS2-L [12], develop similar clinical and radiologic features to those of ALSP; however, some differentiating points were present in the cases with AARS2-L; for example, autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, relatively younger age at onset including childhood onset, and the presence of ovarian failure in all female cases [7, 12, 13]. On brain MRI, white matter rarefaction, tract involvement, spared middle section of the brain, and cerebellar atrophy seemed to be more frequently observed in cases with AARS2 mutation [13]. Brain calcifications observed in ALSP have not been seen in patients with AARS2-L [12]. Only 1 biopsied case showed pathologic findings comparable with ALSP [7], while another biopsied case failed to provide any specific findings [14]. Thus, pathologic characteristics of AARS2-L remain unclear. Notably, mutations in AARS2 can also cause infantile mitochondrial cardiomyopathy [15]. Therefore, further studies would be warranted to determine clinical, radiologic, and even pathologic similarities and differences between ALSP and AARS2-L.

This study had the following limitations. First, we retrospectively extracted the clinical data; thus, there may be variations or bias in the volume of information depending on the medical records or the literature. In particular, the disease duration at the time of applying the criteria varied in cases (we could not calculate the mean disease duration due to insufficient data). If the criteria were applied to patients with the very early stage of the illness, the sensitivity would become lower. Second, except for cases with CADASIL, we could not validate these criteria to cases with other specific leukoencephalopathies. To clarify the differential points among leukoencephalopathies, establishing diagnostic criteria for other leukoencephalopathies and assessing the utility of these criteria for each disease would be preferable.

Comprehensive genetic testing using the panel or exome sequence analyses has become technically available and facilitated genetic diagnosis of adult-onset leukoencephalopathies. While panel testing for these genetic disorders is becoming more popular, its application to clinical practice may be limited due to the cost and availability. Accurate clinical suspicion will facilitate gene testing of the target gene, and eventually reduce the cost and time of diagnostic process. We believe that these criteria are useful for the clinical diagnosis of ALSP; however, the criteria should be validated in larger prospective cohorts and further refined, especially for achieving higher specificity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Scientific Publications of Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville Florida, for their assistance with the technical preparation of this manuscript. We would like to thank Ms. Kelly Viola, MPS, ELS for her assistance with the technical preparation of this manuscript, Dr. Masatoyo Nisizawa from Niigata University for his support throughout the study, Drs. Michiaki Kinoshita and Yasufumi Kondo from Shinshu University, Dr. Daiki Takewaki from Kyoto Prefectural School of Medicine, and Drs. Yuishin Izumi and Ryuji Kaji from Tokushima University for their cooperation in collecting clinical data. We are also thankful to Dr. Jun-ichi Kira from Kyushu University for kindly providing MRI data.

Footnotes

Disclosure of conflicts of interest

T. Konno received research support from JSPS Overseas Research Fellowships and is partially supported by a gift from Carl Edward Bolch, Jr., and Susan Bass Bolch. K. Yoshida, I. Mizuta, T. Mizuno, M. Tada, H. Nozaki, S. Ikeda, M. and O. Onodera report no disclosure relevant to the manuscript. T. Kawarai is supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific research from Japan Society of Promotion of Science, a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, and a Grant-in-Aid from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. Z. Wszolek is supported by the NIH/NINDS P50 NS072187, NIH/NIA (primary) and NIH/NINDS (secondary) 1U01AG045390-01A1, Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine, Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine, Mayo Clinic Neuroscience Focused Research Team (Cecilia and Dan Carmichael Family Foundation, and the James C. and Sarah K. Kennedy Fund for Neurodegenerative Disease Research at Mayo Clinic in Florida), the gift from Carl Edward Bolch, Jr., and Susan Bass Bolch, The Sol Goldman Charitable Trust, and Donald G. and Jodi P. Heeringa. T. Ikeuchi is supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific research from Japan Society of Promotion of Science, a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, and a Grant-in-Aid from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development.

References

- 1.Ahmed RM, Murphy E, Davagnanam I, et al. A practical approach to diagnosing adult onset leukodystrophies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:770–781. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiffmann R, van der Knaap MS. Invited article: an MRI-based approach to the diagnosis of white matter disorders. Neurology. 2009;72:750–759. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000343049.00540.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rademakers R, Baker M, Nicholson AM, et al. Mutations in the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) gene cause hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Nat Genet. 2012;44:200–205. doi: 10.1038/ng.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholson AM, Baker MC, Finch NA, et al. CSF1R mutations link POLD and HDLS as a single disease entity. Neurology. 2013;80:1033–1040. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726a7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Konno T, Yoshida K, Mizuno T, et al. Clinical and genetic characterization of adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia associated with CSF1R mutation. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:37–45. doi: 10.1111/ene.13125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sundal C, Fujioka S, Van Gerpen JA, et al. Parkinsonian features in hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) and CSF1R mutations. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19:869–877. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynch DS, Zhang WJ, Lakshmanan R, et al. Analysis of Mutations in AARS2 in a Series of CSF1R-Negative Patients With Adult-Onset Leukoencephalopathy With Axonal Spheroids and Pigmented Glia. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:1433–1439. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saitoh BY, Yoshida K, Hayashi S, et al. Sporadic hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids showing numerous lesions with restricted diffusivity caused by a novel splice site mutation in the CSF1R gene. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2013;4:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sundal C, Van Gerpen JA, Nicholson AM, et al. MRI characteristics and scoring in HDLS due to CSF1R gene mutations. Neurology. 2012;79:566–574. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318263575a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konno T, Tada M, Tada M, et al. Haploinsufficiency of CSF-1R and clinicopathologic characterization in patients with HDLS. Neurology. 2014;82:139–148. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konno T, Broderick DF, Mezaki N, et al. Diagnostic value of brain calcifications in adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38:77–83. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakshmanan R, Adams ME, Lynch DS, et al. Redefining the phenotype of ALSP and AARS2 mutation-related leukodystrophy. Neurol Genet. 2017;3:e135. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dallabona C, Diodato D, Kevelam SH, et al. Novel (ovario) leukodystrophy related to AARS2 mutations. Neurology. 2014;82:2063–2071. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szpisjak L, Zsindely N, Engelhardt JI, et al. Novel AARS2 gene mutation producing leukodystrophy: a case report. J Hum Genet. 2017;62:329–333. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gotz A, Tyynismaa H, Euro L, et al. Exome sequencing identifies mitochondrial alanyl-tRNA synthetase mutations in infantile mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:635–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.