Abstract

Acute liver failure (ALF) requires urgent attention to identify etiology and determine prognosis, in order to assess likelihood of survival or need for transplantation. Identifying idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury (iDILI) may be particularly difficult, but the illness generally follows a subacute course, allowing time to assess outcome and find a liver graft if needed. Not all drugs that cause iDILI lead to ALF; the most common are antibiotics including anti-tuberculous medications, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents and herbal and dietary supplements (HDS). Determining causality remains challenging particularly if altered mentation is present; identifying the causative agent depends in part on knowing the propensity of the drugs that have been taken in the proper time interval, plus excluding other causes. In general, iDILI that reaches the threshold of ALF will more often than not require transplantation, since survival without transplant is around 25%. Treatment consists of withdrawal of the presumed offending medication, consideration of N-acetylcysteine (NAC), as well as intensive care. Corticosteroids have not proven useful except perhaps in instances of apparent autoimmune hepatitis caused by a limited number of agents. Recently developed prognostic scoring systems may also aid in predicting outcome in this setting.

Keywords: Acute liver failure, drug-induced liver injury, idiosyncratic, hepatotoxicity

Introduction

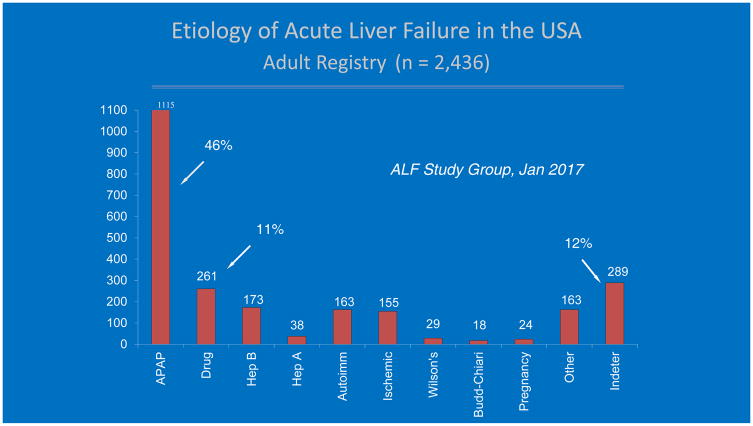

Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury (iDILI) ranks second (11%) in the overall causes of acute liver failure (ALF), behind acetaminophen (APAP)-induced hepatotoxicity (46%) in the United States. Thus, the combined toll of all forms of DILI accounts for more than 50% of all ALF, at least in the Western developed world. (Fig 1)1 Acute liver failure, characterized by coagulopathy with an INR ≥ 1.5 and any degree of hepatic encephalopathy in the absence of chronic liver disease, is exceedingly rare; its overall occurrence is estimated at 1.4 cases per million inhabits per year in Spain to 5.5 cases per million per year or nearly 2000/year for the United States.2,3 APAP and iDILI differ significantly in pathogenesis, clinical course and outcome as well as in frequency, and ease of diagnosis. It is estimated that there are approximately 500 deaths secondary to APAP hepatotoxicity annually in the United States alone.4 Determining the incidence of iDILI ALF is difficult due to underreporting and challenges inherit in retrospective reviews. Prospective population studies report annual incidence of DILI as 13.9 per 100,000 persons in France, 19.1 per 100,000 in Iceland and 12 per 100,000 in Korea.5,6,7 Estimates for actual iDILI-related ALF and deaths in the U.S. are harder to come by, but are likely to be in the range of 300–500 per year. In France, 12% of DILI cases were hospitalized with 6% mortality corresponding to 8,000 cases per year and 500 deaths, whereas Korea reported nearly 6,000 hospitalizations with 1.8% mortality, a little over 100 deaths per year.5,7

Figure 1.

Etiology of acute liver failure in the United States, from the ALFSG registry, 1998–2016, including 2,436 patients. Acetaminophen and DILI are the most common specific etiologies.

The fact that these instances are due to no fault of the afflicted individual makes iDILI a more compelling subject for drug scrutiny, in comparison to APAP toxicity which represents, in many cases, direct self-harm and, in others, instances of polysubstance abuse.8 While the pathogenesis of iDILI remains a mystery, it has been postulated that iDILI, and the very word idiosyncratic, indicate that there must be a unique feature within the patient affected. The fatal drug reaction that the iDILI patient may experience is not of the patient’s own choosing but appears randomly, certainly unexpected, due to unique genetic reasons for each case; however, the specific mechanisms remain to be identified.9 This review will cover several aspects of interest to the clinician related only to idiosyncratic drug-induced acute liver failure and NOT to the milder forms of the disease or to the unique features of APAP ALF: recognition of iDILI ALF, pitfalls in diagnosis and confirming causality, disease categories based on presumed pathogenetic mechanisms, developing a treatment strategy, and prognosis.

Suffice it to say, not all DILI reaches the threshold of ALF. Different networks in the United States, sponsored by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), deal with these two different disease types and we will draw on their experience throughout. The Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) since 2004 has enrolled cases of iDILI of all degrees of severity including those with ALF. While only ~10–15% of the overall number of iDILI cases enrolled fulfilled ALF criteria, up to 10% will still die or require liver transplantation. Those with pre-existing liver disease do less well with 16% mortality compared to 5.2% for those without such issues.10 By contrast, the Acute Liver Failure Study Group (ALFSG) network since 1998 has enrolled only cases with ALF of all etiologies (and, since 2009, a severe form of liver dysfunction with INR>2 but without encephalopathy, called acute liver injury [ALI]), of which only 6% of ALI and 11% of ALF cases are believed due to iDILI.11

Challenges in diagnosis and causality assignment

Both DILI and ALF diagnoses may be missed by the first medical contact a patient seeks out, for a variety of reasons. On the patient’s side, associating an illness with something one takes to help alleviate (not cause) problems seems counter-intuitive. DILI occurs after a certain interval so that the drug may no longer be in use, but still begin to manifest symptoms. If the patient has any degree of encephalopathy (ALF), then he or she can hardly recall what they may have ingested recently. Determination of causality is based on circumstantial inference, guilt-by-association: if the patient began taking something new, became sick, then stopped and began to improve, it would seem reasonable that the drug was the cause of the sickness. However, many other stories are plausible: infection, other toxin exposure, other drug exposure besides the one being implicated, gallstones, alcohol use or abuse. Since there is no specific test to confirm that an acute liver illness is due to a drug, scoring systems have been constructed to allow adjudication of the likelihood of a drug causing an instance of iDILI.12 For ALF, the diagnosis must be made quickly since deterioration is the rule and transfer to a higher level of care for consideration of transplantation must be undertaken. In ALF, altered mentation is unexpected and its cause can be misunderstood to be psychiatric or related to mind-altering drugs. Once an INR is drawn, and returns elevated or jaundice is recognized as possibly related to the mental alteration then the diagnosis becomes clearer. Again, the patient with DILI ALF may not be able to cooperate with determining the specific agent causing the injury. Features that help relate a drug ingestion to the liver injury primarily involve timing (did the injury occur at a suitable latency), exclusion of other causes (viruses, other drugs, gallstones, alcohol) and the likelihood that the implicated drug causes the injury in question.12 Recent work by the DILIN group has focused on the process of determining likelihood. So far, there is no score but ‘expert opinion’ which is a cumbersome process and not adaptable to the bedside analysis of cases.13 Further efforts have focused on what constitutes the adequate and complete workup, identifying ‘minimal elements’, tests that should be performed, mainly to exclude other diagnoses.14 More recently, drugs have been catalogued by how many reports of injury have surfaced for a given drug; this depends on how often the drug is used as well as how toxic the drug may be. For example, a highly cytotoxic cancer drug will have fewer uses compared to a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory or a hypertensive medication, but the former will often have a much higher propensity for injury, per patient use.15 The net effect on the population is the combination of the two: likelihood of toxicity and frequency of use. In a study from Iceland, the most frequently named drug causing DILI was amoxicillin/clavulanate, since it is commonly used and has a relatively frequent likelihood of causing injury, but seldom if ever causes ALF.6

In regard to DILI-related ALF, a specific path forward to catalogue specific causative agents and further refine causality has not been determined. In an earlier overview paper of 133 patients with ALF due to DILI, expert opinion was used to adjudicate.1 More recently, ALFSG has developed a more focused causality assessment process which requires specific features to be determined for all etiologies for a patient to be classified as highly likely/definite or when fewer criteria are met, probable. In this process, the review committee has moved past using the site investigator’s presumed diagnosis and has often been able to reassign nearly a quarter of indeterminate cases to a specific etiology including a specific drug by reviewing carefully for additional information not present during the initial evaluation.16 Expert opinion still holds sway. In DILIN parlance, Definite is > 95% likelihood, highly likely 75–95%, probable 50–75% likely, that is, more than 50% hence the term probable. For most ALF etiology diagnoses, the criteria are more straightforward than they are for DILI cases. This points up the difficulty with iDILI ALF—no diagnostic test! Thus, we fall back on DILIN guidelines for diagnosis, requiring, in effect, expert opinion and the relative certainty that non-drug causes have been adequately excluded. The important point, which cannot be over-emphasized, is to question the patient and family repeatedly, since the report of some new medication or herbal remedy often is not elicited by the first or even the second or third history-taker.

The pattern of injury that suggests iDILI, whether ALF or a milder form, is a sub-acute pattern that evolves over a week or more, rarely demonstrating the very high enzyme levels (> 3,500 IU/L for aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase), that characterize APAP-related injury. Encephalopathy may not be evident at time of initial presentation of iDILI but develops after days to weeks in the setting of continued modest transaminase elevation with moderate jaundice and an elevated INR. Hy’s law, most simply hepatocellular DILI reaching the threshold of jaundice, defines an intermediate level of severity not quite meeting ALF criteria, but significant injury such that death occurs in nearly 10%. Virtually all iDILI cases meeting Hy’s law criteria should be hospitalized.17 Hepatocellular jaundice forewarns the development of ALF, death and transplant in numerous studies.18–19 A typical example of this is isoniazid that has a uniform phenotype of hepatocellular injury of increasing severity to ALF and present on all continents, given the widespread use of the drug. In the Spanish DILI Registry, a New Prognostic Algorithm utilizing AST over 17.3 x ULN, bilirubin over 6.6 x ULN and AST to ALT ratio greater than 1.5 has been proposed that identified ALF in 4.1% of cases with 82% specificity and 80% sensitivity.20 Additional factors associated with poorer outcomes in iDILI include female gender, older age, Asian ethnicity, thrombocytopenia and history of chronic liver disease.10,18–19

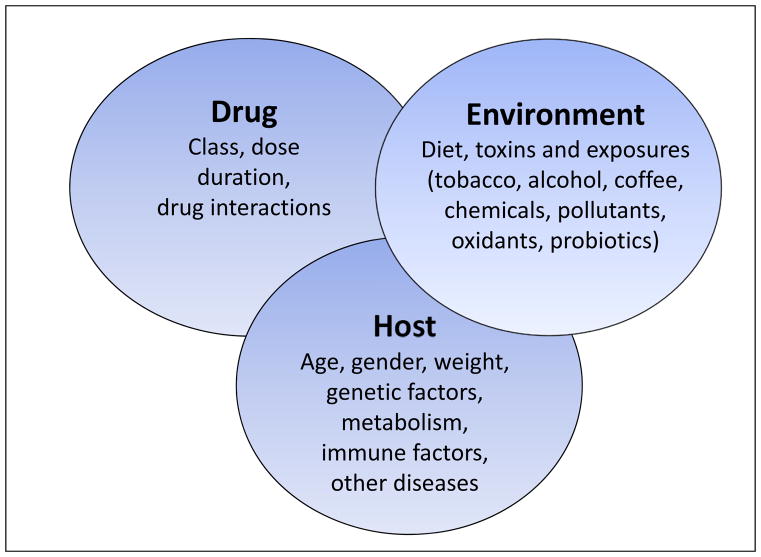

Liver biopsy is often proposed as of possible help in identifying DILI ALF cases; however, in addition to the relative risk in this setting, the findings in many instances are non-specific, consisting of widespread apoptotic necrosis with lymphocyte infiltration and varying degrees of cholestasis--findings not too dissimilar from that of severe viral hepatitis.21 The presence of eosinophils may be observed and serves as a clue to the DILI etiology.22 The search for biomarkers that might be specific for iDILI has still been of limited value.23 Micro-RNAs such as miR-122 are very abundant, primarily in hepatocytes, and are observed in increased quantity in iDILI and viral hepatitis plasma but also in APAP-related injury, more so in APAP, suggesting that their presence in serum is passive, representing release of miR-122 from damaged cells similar to AST and ALT.24 Antibodies to isoniazid (INH) can be demonstrated in some patients with INH-related ALF but these assays currently represent research tools only.25 Part of the problem with iDILI research is that it is not one disease but hundreds of somewhat similar diseases. Even patients suffering from a specific drug-related injury may not have the same disease pattern or response to cessation of the agent (Figure 2). An antibody test that might be helpful diagnostically for isoniazid would not be relevant for other drugs; besides which many clinicians diagnose iDILI due to INH with relative certainty despite the potential pitfalls involved. Thus, biomarker development is either too difficult or there is not a need for it. Likewise, genome wide association studies (GWAS) have identified some HLA haplotypes that are present with increased frequency in patients suffering from iDILI due to a specific drug. Translating this to a worthwhile test has proven fruitless thus far, in part because other drugs are often available that lack the toxicity of the suspect agent, given the cumbersome nature of genetic testing prior to use of an agent.9,26,27

Figure 2.

Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury involves the interplay of host, drug and environment. Reproduced with permission from Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:202–11.

Role of complementary and alternative medications

Traditional herbal medicine is prevalent in many parts of Asia and is implicated in over 70% of iDILI cases though historically rarely results in death or transplant.7,28 Durrently in China, drugs in the broadest sense are reportedly the most common cause of ALF, with the majority attributed to herbal toxicity and having a high mortality.29 Herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) are used increasingly in the U.S. and Europe and, unlike prescription drugs, are unregulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).30 Recent evidence suggests an increasing contribution of supplements to iDILI, comprising 20% of cases in DILIN in 2010–2012 compared to 7% in 2004–2005.31 Taking non-prescription xenobiotics may not be considered worth mentioning, or patients are reluctant to reveal use to physicians, further impeding the correct diagnosis. In US ALFSG, HDS are responsible for approximately 20% of all iDILI-related ALF, up from 12% a decade ago. What is more concerning is that when HDS injury results in ALF, outcomes are poorer than DILI due to prescription drugs, with only 17% spontaneous survival vs. 34%.32 This is largely related to the toxic ingredients found in many products marketed for weight loss. Several recent ‘epidemics,’ (case series) have been described.33,34 While anabolic steroids used in muscle building products result in prolonged jaundice and are frequently implicated as a cause of HDS induced DILI, this injury does not lead to ALF.31,35

Pathogenesis informs disease pattern and outcome

APAP and iDILI ALF have different pathogeneses, the former being consider a direct or intrinsic toxin and the latter an indirect or extrinsic one. Better terms might be necrosis contrasted with apoptosis but this remains controversial.36 Suffice it to say that APAP has several unique characteristics: dose-related, with very short latency (onset at 24–36 hours, peak at 72–96 hours), followed by rapid recovery or death.37 By contrast, iDILI evolves over time with no specific latency. Generally, injury begins 7–14 days after first ingestion, is not dose-related in the way that APAP is, and with slower onset, results in higher bilirubin levels and, overall, lower aminotransferases. The shortest latencies for idiosyncratic drugs are around 2–4 days, which may be seen with quinolone and macrolide antibiotics or anesthetics but in very few other instances.38,39 Many latencies are as long as 90 days from ingestion to onset of injury and illness.40 Table 1 demonstrates the differences between APAP and iDILI in an analysis from the ALFSG. Likewise, these different pathogenetic mechanisms lead to different outcomes. The slower the evolution, the longer the time that the injury continues to occur, the poorer the outcomes. Evidence of improvement after cessation of a drug is often delayed for weeks if it occurs at all.

Table 1.

Clinical and biochemical characteristics of APAP vs iDILI Acute Liver Failure, based on 2,436 patients enrolled in the ALFSG, 1998–2016.

| APAP N=1115 |

Drug n=261 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (median) | 37 | 46 |

| Sex (% F) | 76 | 69 |

| Jaundice to coma (Days) | 1 | 12 |

| Coma ≥3 (%) | 53 | 36 |

| ALT (median IU) | 3798 | 648 |

| Bili (median) | 4.3 | 19.2 |

| Tx (%) | 8.6 | 38 |

| Spontaneous Survival (%) | 64.4 | 25 |

| Overall Survival (%) | 71.5 | 59 |

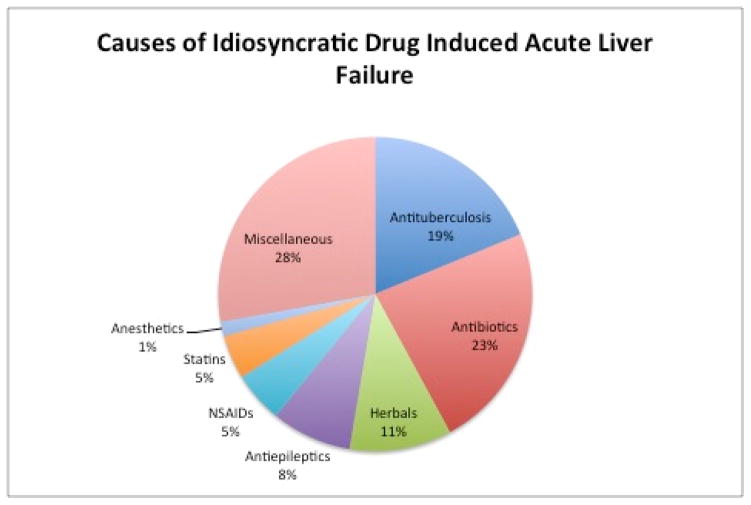

Agents most commonly implicated in iDILI ALF depend on prescribing patterns and the underlying patient population.41 The most frequent culprits of iDILI ALF in the ALFSG are anti-tuberculosis medications, other antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiepileptic medications. (Figure 3).1 A retrospective review of ALF in Germany reported phenprocoumon, a coumarin derivative, as the predominant cause of iDILI ALF.42 In Latin America, flutamide, cyproterone acetate and nimesulide are responsible for the majority of iDILI ALF.43 Anti-tuberculosis therapy is the most common iDILI-associated ALF in South Asia and the developing world, probably related to more frequent need for these agents in endemic areas.44 Up to a quarter of iDILI due to tuberculosis treatment progresses to ALF with high mortality rate.45 A wide variety of agents have been implicated including other classes, ranging in pathogenesis from autoimmune to hypersensitivity and mitochondrial injury mechanisms (Table 2). A number of features implicate acquired immunity in iDILI with association of susceptible human leukocyte antigen genotypes but evidence of antibodies directed at drug-specific targets on cells has been identified infrequently.9

Figure 3.

Drug classes causing idiosyncratic DILI-related ALF, by frequency (reference 1). The largest categories are antibiotics, both general as well as those specific to tuberculosis treatment.

Table 2.

Some drugs that may cause idiosyncratic acute liver failure

Drugs implicated in acute liver failure, partial list compiled from ALFSG and DILIN registries.

| Antimicrobial Agents | Biological Agents |

|---|---|

| Antituberculosis drugs | Gemtuzumab |

| Isoniazid | Ipilimumab |

| Rifampin | Statins |

| Dapsone | Atorvastatin |

| Pyrazinamide | Cervistatin |

| Antibiotics | Simvastatin |

| Sulfonamides | Miscellaneous Drugs |

| Nicotinic acid | Propylthiouracil |

| Nitrofurantoin | Disulfiram |

| Amoxicillin | Troglitazone |

| Levaquin | Methyldopa |

| Ciprofloxacin | Allopurinol |

| Ofloxacin | Amiodarone |

| Clarithromycin | Labetalol |

| Telithromycin | Lisinopril |

| Antifungals | Flutamide |

| Terbinafine | Azathiopurine/mercaptopurine |

| Itraconazole | Nicotinic acid |

| Ketaconazole | Etoposide |

| Anti-retrovirals | Tolcapone |

| Didanosine | Cocaine |

| Stavudine | Methylenedioxymetamphetamine (MDMA: “Ecstasy”) |

| Efavirenz | Herbal and dietary supplements* |

| Fluoxetine | Anti-epileptics |

| Imipramine | Phenytoin |

| Anesthetics | Valproic acid |

| Halothane | Carbamazepine |

| Isoflurane | Tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitors |

| Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | Imatinib |

| Diclofenac | Nilotinib |

| Etodolac | Ponatinib |

| Psychotropic agents | |

| Quetiapine | |

| Nefazodone |

Some herbal products/dietary supplements that have been associated with hepatotoxicity include: products containing green tea extract, usnic acid, ephedra, and multi-ingredient products marketed for weight loss and others.

A particular challenge is separating iDILI due to conventional hepatocellular injury from iDILI related autoimmune hepatitis and from autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) itself. Some pointers may help: in iDILI, there may be positive auto-antibodies (primarily anti-nuclear or anti-smooth muscle but also anti-mitochondrial antibodies) but the titers are usually modest. Autoimmune hepatitis due to iDILI or primary AIH should have higher antibody titers and elevated immunoglobulin G levels. The key to autoimmune hepatitis caused by a drug is that there is a short-list of drugs implicated that should be divulged by a careful history: nitrofurantoin, minocycline, alpha methyldopa and hydralazine are classic, although statins and the newer biologic checkpoint inhibitors are also reported.46 Primary AIH presenting as ALF seldom responds to steroid therapy, whereas milder versions of AIH usually do, and most instances of autoimmune-type DILI do respond to withdrawal of drug and seldom reach the stage of ALF. In the 88 AIH DILI cases described by the DILIN network, 25% had severe injury with the majority secondary to nitrofurantoin.46 Similarly, among the 132 patients enrolled in the ALFSG over the first 10 years, 12 attributed to nitrofurantoin, 2 to methyldopa, one to hydralazine and none to minocycline.1

Disease pattern and outcome/prognosis

Etiologies of ALF can be divided into those associated with favorable outcomes and those that have unfavorable outcomes. This grouping based at least partly on pathogenetic types places APAP, ischemic injury to the liver (shock), hepatitis A and ALF related to pregnancy in the favorable category, with all having ≥ 60% short term transplant free survival. All equally have acute or hyperacute presentations and, generally, recover rapidly. By comparison iDILI, AIH, hepatitis B and indeterminate cases all have subacute presentation and poorer outcomes with less than 40% survival without transplantation (Table 1).47 This finding lead to a more extensive analysis with the goal of finding a better determinant of outcome than current models such as MELD or Kings College Hospital (KCH) criteria. In the ALFSG, the four parameters, etiology group (favorable/unfavorable), use of pressors, bilirubin and INR effectively predicted outcome, giving a percentage likelihood of transplant free survival with an ROC of 0.84.48 The ALFSG prognostic index has improved prediction of outcome, with more favorable ROC curve than MELD or KCH—this is readily available as an iPhone app on the Apple iTunes website under ‘ALF Prognosis.’ The ALFSG prognostic index was tested in UK patients with favorable results--scoring systems can never fully substitute for clinical judgment but serve as adjuncts to help measure severity.49 While new biomarkers are identified almost daily, translating them into clinically useful prognostic tools remains challenging.50

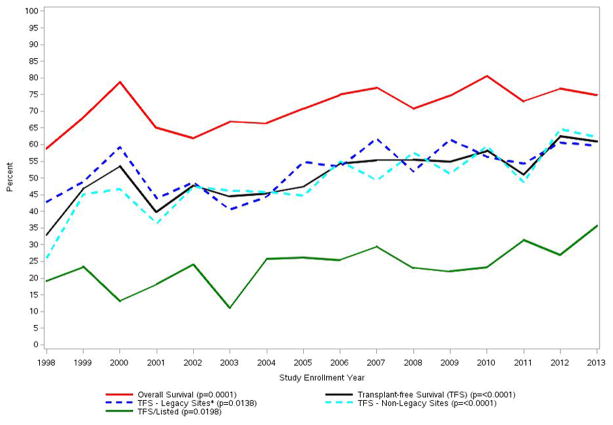

As has been noted, iDILI clearly carries a worse prognosis for survival than APAP. In the early days of the ALFSG study, only 26.8% of iDILI patients survived without transplantation and 42% received a graft, while 31% died. The subacute nature and evolution of iDILI ALF favors transplantation in comparison to the hyperacute evolution of APAP cases as noted above. As noted, over the past 16–20 years, overall outcomes have improved although the reasons for this remain unclear. Severity of illness at presentation was similar in the ALFSG study over the 16-year period; however, transplants and listing for transplants declined and overall survival improved (Figure 4a). Improved survival was despite less use of aggressive intensive care with fewer patients receiving blood product transfusion, or requiring ventilator or pressor support. (Figure 4b). The iDILI group specifically improved its transplant-free survival from 26.8% to 41.4% between the earlier and later 8-year study periods (p <0.022), a more dramatic improvement than the other non-APAP categories. In parallel, the number transplanted declined: 25% of iDILI patients were transplanted between 1998 and 2005 vs. 19.8% in the later era, while the overall number of deaths declined as well. This was consonant with the increase in NAC use over the same 16-year period but may or not be related to that fact (Figure 4c).47

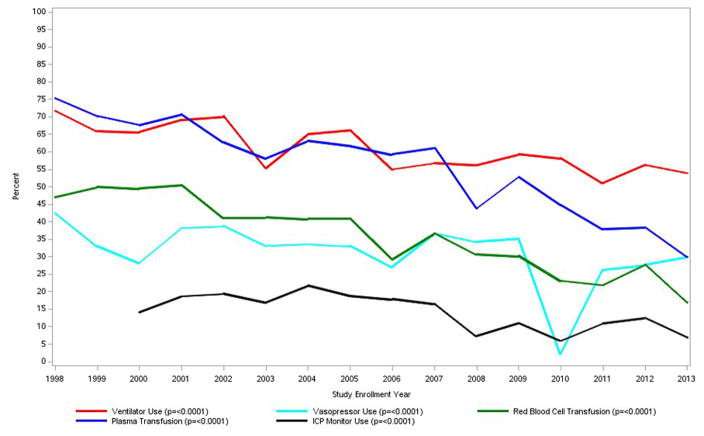

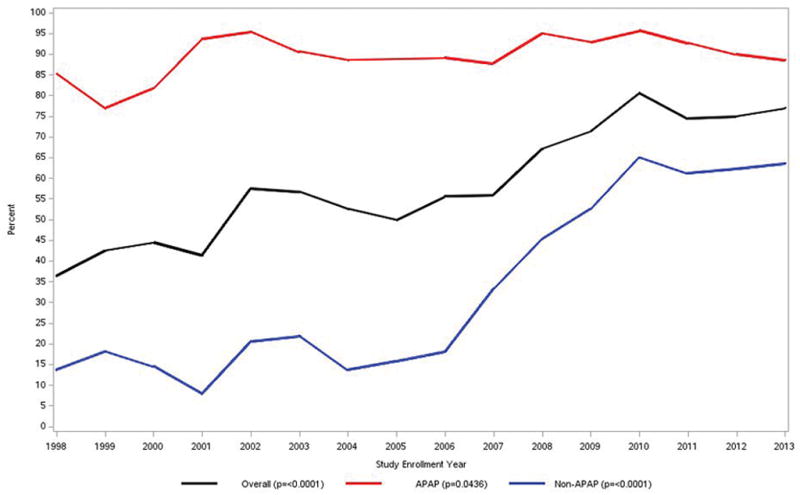

Figure 4.

a. Trends in overall outcome, transplant listing and transplantation in acute liver failure in the US over time, 1998–2013, 2070 patients; note difference in patient count shown in other Figures/Tables—2,436 from 1998–2016.

b. Trends over time in intensive care support including ventilator or pressor use, as well as transfusion of blood or plasma.

c. Use of NAC for APAP and non-APAP ALF and overall use over time from 1998–2013. An increase of NAC use for non-APAP ALF was observed after 2006. (Figures 4a–c reproduced from reference 39, Ann Intern Med 2016:164:724–732 with permission.) Number

*Legacy sites have enrolled at least one subject in each of the 16 years of the registry. They include: Northwestern University, University of California at San Francisco, University of Michigan, University of Washington, and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Note that p-values represent trends over time tested with the Cochran-Armitage test.

Treatment for iDILI ALF

Initial treatment for any DILI setting is to withdraw the drug or drugs that might be implicated, regardless of whether there is certainty about the causality association. The next question is whether there is value in any generic treatment modality for all ALF or at least for all DILI-related ALF. Among the choices are corticosteroids and N-acetylcysteine. Overall management of DILI has recently been reviewed.40

Corticosteroids are often given when all else fails to produce results. Most early trials during the last century were of all forms of ALF with no benefit shown; however, to some extent these included patients with hepatitis B whom we would not consider for steroid therapy in the current era.51 A recent paper summarizing retrospective data for the overall ALFSG registry cohort did not demonstrate any survival benefit for steroid usage but did not single out iDILI cases.52 To date, no controlled trial of corticosteroid use in this setting has been reported.

The possible benefit of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has been debated over the years—recommendations remain mixed at this time. A randomized controlled trial of NAC in adults with non-APAP ALF demonstrated efficacy in diminishing the number of deaths and transplants for patients with early grade encephalopathy. The percent spontaneous survival increased from 30 to 52% in the coma grade I–II group, although the overall and spontaneous survival of all coma grades were not significantly improved. Of note, the DILI ALF subgroup within the NAC trial showed the most promising beneficial effect—spontaneous or transplant-free survival increasing from 27 to 58% with NAC treatment.53 Two similar trials in children showed no efficacy.54,55 A meta-analysis indicated limited benefit to use of NAC but, again, this had limited data beyond the one adult trial mentioned, grouping two pediatric trials with two adult trials.56 Further data has suggested a mechanism for the effect of NAC.57,58 Despite calls for one, it is highly unlikely that another randomized controlled trial will be performed for the super-orphan condition of ALF, let alone for iDILI ALF. Overall, there is no certain or specific treatment for iDILI ALF except good care of the critically ill patient, but NAC is commonly used, given its impressive safety profile.

Summary

Although only 10% of iDILI will progress to ALF, stakes are high with more than 60% needing a transplant or dying from progressive liver failure. Drugs remain the most common cause of ALF in the Western world. With the exception of acetaminophen, severity of liver injury is unpredictable, not specifically related to dose, and requires a high index of suspicion and exclusion of other etiologies to make the diagnosis. Antimicrobials, anticonvulsants, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and herbals are most commonly implicated in iDILI ALF. Detection of susceptible human leukocyte antigen genotypes as well as autoimmune phenotypes point to immune mediated mechanism of iDILI but this remains an area for future investigation.27 Treatment largely centers on withdrawal of the suspected agent(s) and supportive care, but NAC should be considered as well as timely evaluation for liver transplant.

Key Points.

iDILI-related ALF is a rare cause of ALF worldwide but requires careful evaluation since outcomes are worse than for most other forms of ALF.

iDILI ALF follows a subacute course, since the pathogenesis appears to be immune mediated.

Prompt evaluation to determine etiology and severity is important as well as good coma care, in improving outcomes.

N-acetylcysteine appears to have benefit for early stage ALF not due to acetaminophen.

Use of prognostic scores may help determine need for transplantation in iDILI ALF.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The Acute Liver Failure Study Group is funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disesases (NIDDK) U-01-58369.

Abbreviations

- ALF

acute liver failure

- iDILI

idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury

- HDS

herbal and dietary supplements

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- APAP

acetaminophen

- INR

international normalized ratio

- NIH

National Institutes for Health

- DILIN

Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network

- ALFSG

Acute Liver Failure Study Group

- ALI

acute liver injury

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- ULN

upper limit normal

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- INH

isoniazid

- GWAS

genome wide association studies

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: SRT nothing to disclose. WML consulting: Lilly, Novartis, Repros

References

- 1.Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM the Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Drug-induced acute liver failure: Results of a United States multicenter prospective study. Hepatology. 2010;52:2065–78. doi: 10.1002/hep.23937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escorsell A, Mas A, de la Mata M Spanish Group for the Study of Acute Liver Failure. Acute liver failure in Spain: analysis of 267 cases. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1389–95. doi: 10.1002/lt.21119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bower WA, Johns M, Margolis HS, Williams IT, Bell BP. Population-based surveillance for acute liver failure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2459–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nourjah P, Ahmad SR, Karwoski C, Willy M. Estimates of acetaminophen (Paracetamol)-associated overdoses in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:398–405. doi: 10.1002/pds.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sgro C, Clinard F, Ouazir K, et al. Incidence of drug-induced hepatic injuries: a French population-based study. Hepatology. 2002;36:451–55. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjornsson ES, Bergmann OM, Bjornsson HK, Kvaran RB, Olafsson S. Incidence presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterol. 2013;144:1419–25. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suk KT, Kim JD, Kim CH, et al. A prospective nationwide study of drug-induced liver injury in Korea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1380–87. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larson AM, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, et al. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: Results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2005;42:1367–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urban TJ, Daly AK, Aithal GP. Genetic basis of drug-induced liver injury: present and future. Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34:123–33. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1375954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, et al. Features and outcomes of 899 patients with drug-induced liver injury: The DILIN prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1340–52. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koch DG, Speiser JL, Durkalski V, et al. The natural history of severe acute liver injury. Am J Gastroenterol. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.98. advance online publication, 25 April 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs—I. A novel method based on the conclusions of international consensus meetings: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1323. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockey DC, Seeff LB, Rochon J, et al. Causality assessment in drug-induced liver injury using a structured expert opinion process: comparison to the Roussel-Uclaf causality assessment method. Hepatology. 2010;51:2117–26. doi: 10.1002/hep.23577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal VK, McHutchison, Hoofnagle JH. Important elements for the diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury. Clin Gastro Hep. 2010;8:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjornsson ES, Hoofnagle JH. Categorization of drugs implicated in causing liver injury: Critical assessment based on published case reports. Hepatology. 2016;63:590–603. doi: 10.1002/hep.28323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganger D, Rule JA, Bass NM, et al. Solving indeterminate etiology in acute liver failure: The contribution of expert opinion to the process of causality adjudication. Hepatology. 2016;64(Suppl 51):52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Temple R. Hy’s Law: predicting serious hepatotoxicity. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:241–3. doi: 10.1002/pds.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrade RJ, Lucena MI, Fernández MC, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: an analysis of 461 incidences submitted to the Spanish registry over a 10-year period. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:512–21. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fontana RJ, Hayashi PH, Gu J, et al. Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality within 6 months from onset. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:96–108. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robles-Diaz M, Lucena MI, Kaplowitz N, et al. Use of Hy’s law and a new composite algorithm to predict acute liver failure in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:109–118. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleiner DE, Chalasani NP, Lee WM, et al. Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) Hepatic histological findings in suspected drug-induced liver injury: Systematic evaluation and clinical associations. Hepatology. 2014;59:661–70. doi: 10.1002/hep.26709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefkowitch JH. The pathology of acute liver failure. Adv Anat Pathol. 2016;23:144–58. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosedale M, Watkins P. Drug-induced liver injury: Advances in mechanistic understanding that will inform future risk management. Clin Pharm Therapeut. 2017;0:0. doi: 10.1002/cpt.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thulin P, Nordahl G, Gry M, et al. Keratin-18 and microRNA-122 complement alanine aminotransferase as novel safety biomarkers for drug-induced liver injury in two human cohorts. Liver Int. 2014;34:367–78. doi: 10.1111/liv.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metushi IG, Sanders C, Lee WM, Uetrecht J. Detection of anti-isoniazid and anti-cytochrome P450 antibodies in patients with isoniazid-induced liver failure. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1084–93. doi: 10.1002/hep.26564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singer JB, Lewitzky S, Leroy E, et al. A genome-wide study identifies HLA alleles associated with lumiracoxib-related liver injury. Nat Genetics. 2010;42:711–14. doi: 10.1038/ng.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicoletti P, Aithal GP, Bjornsson ES, et al. Association of liver injury from specific drugs, or groups of drugs, with polymorphisms in HLA and other genes in a genome-wide association study. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1078–89. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wai CT, Tan BH, Chan CL, et al. Drug-induced liver injury at an Asian center: a prospective study. Liver Int. 2007;27:465–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao P, Wang C, Liu W, et al. Causes and Outcomes of Acute Liver Failure in China. In: Avila MA, editor. PLoS ONE. 11. Vol. 8. 2013. p. e80991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navarro VJ. Herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29:372–82. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navarro VJ, Barnhart H, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Liver injury form herbals and dietary supplements in the U.S Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Hepatology. 2014;60:399–408. doi: 10.1002/hep.27317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hillman L, Gottfried M, Whitsett M, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of complementary and alternative medicine induced acute liver failure and injury. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:958–65. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fong TL, Klontz KC, Canas-Coto A, et al. Hepatotoxicity due to Hydroxycut: A case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1561–6. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidemann LA, Navarro VJ, Ahmad J, et al. Severe acute hepatocellular injury attributed to OxyELITE Pro: A Case Series. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2741–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4181-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robles-Diaz M, Gonzalez-Jimenez A, Medina-Caliz I, et al. Distinct phenotype of hepatotoxicity associated with illicit use of anabolic androgenic steroids. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:116–125. doi: 10.1111/apt.13023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan L, Kaplowitz N. Mechanisms of drug-induced liver injury. Clin Liver Dis. 2013;17:507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy KR, Ellerbe C, Schilsky M, et al. Determinants of outcome among patients with acute liver failure listed for liver transplantation in the US. Liver Transpl. 2015;22:505–15. doi: 10.1002/lt.24347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orman ES, Conjeevaram HS, Vuppalanchi R, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features of fluoroquinolone-induced liver injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. [Accessed June 10, 2017];LiverTox.nih.gov. Available from https://livertox.nlm.nih.gov//Halothane.htm.

- 40.Chalasani N, Hayashi PH, Bonkovsky HL, Navarro VJ, Lee WM, Fontana RJ. ACG Clinical Guideline: The diagnosis and management of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:950–966. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki A, Andrade RJ, Bjornsson E, et al. Drugs associated with hepatotoxicity and their reporting frequency of liver adverse events in VigiBase™. Drug Safety. 2010;33:503–522. doi: 10.2165/11535340-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hadem J, Tacke F, Bruns T, et al. Etiologies and outcomes of acute liver failure in Germany. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:664–669. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hernández N, Bessone F, Sánchez A, et al. Profile of idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury in Latin America: an analysis of published reports. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13:231–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar R, Shalimar, Bhatia V, et al. Antituberculosis therapy-induced acute liver failure: magnitude, profile, prognosis, and predictors of outcome. Hepatology. 2010;51:1665–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.23534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Devarbhavi H, Singh R, Patil M, et al. Outcome and determinants of mortality in 269 patients with combination anti-tuberculosis drug-induced liver injury. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:161–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Boer YS, Kosinski AS, Urban TJ, et al. Features of autoimmune hepatitis in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reuben A, Tillman H, Fontana RJ, et al. Outcomes in adults with acute liver failure (ALF) from 1998–2013: An observational cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:724–32. doi: 10.7326/M15-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koch DG, Tillman H, Durkalski V, Lee WM, Reuben A. Development of a model to predict transplant-free survival of patients with acute liver failure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1199–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bernal W, Donnelly MC, Durkalski-Mauldin VL, Simpson K, Wang Y, Wendon J. External validation of the USALFSG acute liver failure outcome prediction criteria. J Hepatol. 2017;66(Suppl 1):S343–S344. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kullak-Ublick G, Andrade RJ, Merz M, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: recent advances in diagnosis and assessment. Gut. 2017;66:1154–64. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rakela J, Mosley JW, Edwards VM, Govindarajan S, Alpert E. A double-blinded randomized trial of hydrocortisone in acute hepatic failure. The Acute Hepatic Failure Study Group. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1223–28. doi: 10.1007/BF01307513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karkhanis J, Verna EC, Chang MS, et al. Steroid use in acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2014;59:612–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.26678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee WM, Hynan LS, Rossaro L, et al. Intravenous N-acetylcysteine improves transplant-free survival in early stage non-acetaminophen acute liver failure. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:856–864. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Squires RH, Dhawan A, Alonso E, et al. Intravenous N-acetylcysteine in pediatric patients with non-acetaminophen acute liver failure: a placebo-controlled clinical trial. Hepatology. 2013;57:1542–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.26001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kortsalioudaki C, Taylor RM, Cheeseman P, Bansal S, Mieli-Vergani G, Dhawan A. Safety and efficacy of N-acetylcysteine in children with non-acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:25–30. doi: 10.1002/lt.21246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu J, Zhang Q, Ren Z, Sun Z, Quan Q. Efficacy and safety of acetylcysteine in “non-acetaminophen” acute liver failure: A meta-analysis of prospective clinical trials. Clin Research Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39:594–99. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh S, Hynan LS, Lee WM the ALFSG. Improvements in hepatic serological biomarkers are associated with clinical benefit of intravenous N-acetylcysteine in early stage non-acetaminophen acute liver failure. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1397–1402. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2512-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stravitz RT, Sanyal AJ, Reisch J, et al. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on cytokines in non-acetaminophen acute liver failure: potential mechanism of improvement in transplant-free survival. Liver Int. 2013;33:1324–31. doi: 10.1111/liv.12214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]